Role of Ethical Leadership in Improving Employee Outcomes through the Work Environment, Work-Life Quality and ICT Skills: A Setting of China-Pakistan Economic Corridor

Abstract

:1. Introduction

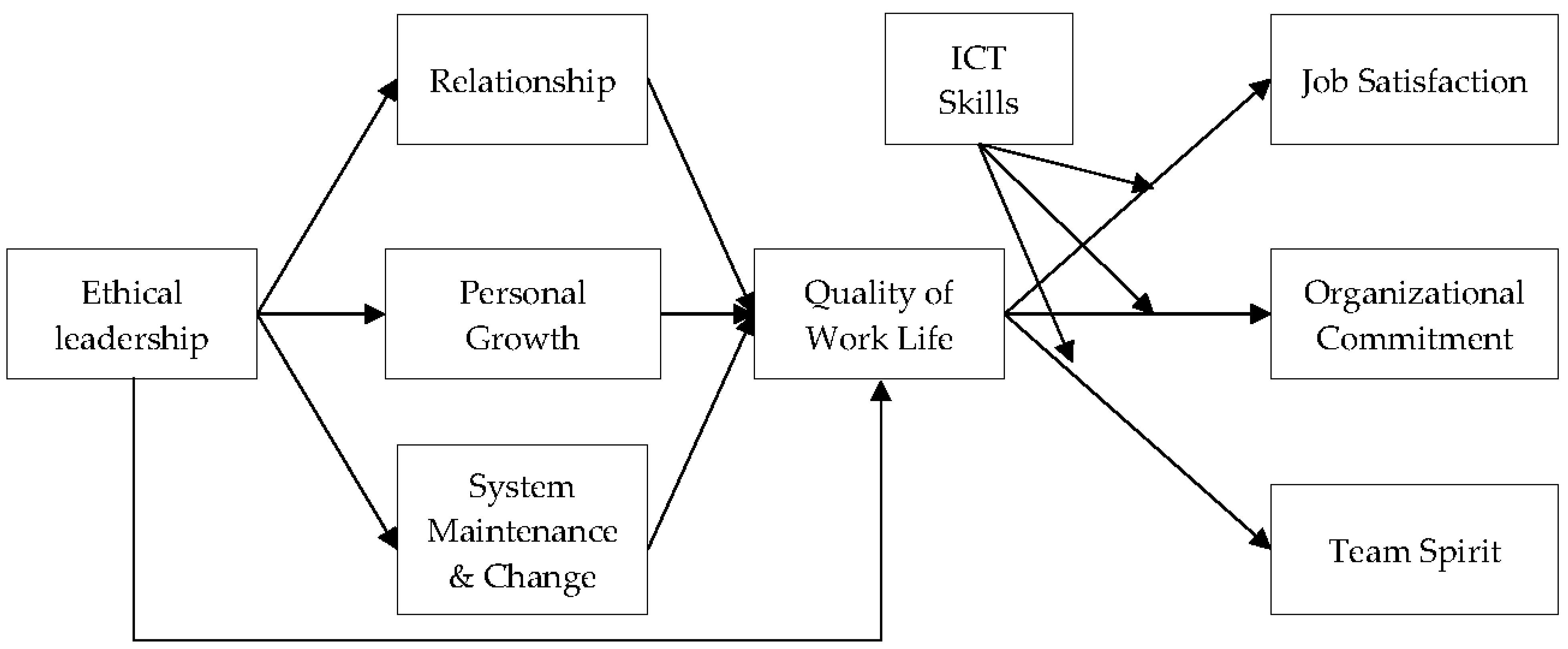

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Ethical Leadership and Work Environment

2.2. Work Environment and Quality of Work-Life

2.3. Ethical Leadership and Quality of Work-Life

2.4. Quality of Work-Life and Job-Related Outcomes

2.5. Moderating Effect of ICT Skills

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

4. Statistical Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.2. Validity and Reliability Analysis

4.3. Goodness of Fit

4.4. Path Measurement Model Analysis

4.5. Specific Indirect Path Analysis

5. Findings and Discussion

Theoretical and Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ranjan, A. The China-Pakistan economic corridor: India’s options. Inst. Chin. Stud. 2015, 10, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, S.; Rafiq, M.; Quddus, A.; Ahmad, N.; Pham, P.T. China-Pakistan economic corridor: Cooperate investment development and economic modernization encouragement. J. Contemp. Issues Bus. Gov. 2021, 27, 96–108. [Google Scholar]

- Syed, J.; Ying, Y. (Eds.) China’s Belt and Road Initiative in a Global Context Volume II: The China Pakistan Economic Corridor and Its Implications for Business; Palgrave Macmillan Cham: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan Marri, M.Y.; Mahmood Sadozai, A.; Fakhar Zaman, H.; Yousufzai, M.; Ramay, M.I. Measuring Islamic work ethics and its consequences on organizational commitment and turnover intention an empirical study at public sector of Pakistan. Int. J. Manag. Sci. Bus. Res. 2013, 2, 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, H.S.; Cunningham, C.J. Linking nurse leadership and work characteristics to nurse burnout and engagement. Nurs. Res. 2016, 65, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawirosumarto, S.; Sarjana, P.K.; Gunawan, R. The effect of work environment, leadership style, and organizational culture towards job satisfaction and its implication towards employee performance in Parador Hotels and Resorts, Indonesia. Int. J. Law Manag. 2017, 59, 1337–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priarso, M.T.; Diatmono, P.; Mariam, S. The effect of transformational leadership style, work motivation, and work environment on employee performance that in mediation by job satisfaction variables in PT. Gynura Consulindo. Bus. Entrep. Rev. 2018, 18, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgren, D.; Ernsth-Bravell, M.; Kåreholt, I. Leadership and the psychosocial work environment in old age care. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2016, 11, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moos, R.H. Person-environment congruence in work, school, and health care settings. J. Vocat. Behav. 1987, 31, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holahan, C.J.; Moos, R.H. Life stressors, personal and social resources, and depression: A 4-year structural model. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1991, 100, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerman, J.W.; Yamamura, J.H. Generational preferences for work environment fit: Effects on employee outcomes. Career Dev. Int. 2007, 12, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerman, J.W.; Cyr, L.A. An integrative analysis of person–organization fit theories. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2004, 12, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belicki, K.; Woolcott, R. Employee and patient designed study of burnout and job satisfaction in a chronic care hospital. Empl. Assist. Q. 1996, 12, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmeti, I.; Telaku, M. Relation of the perception of work environment with job satisfaction: The case of teachers in high schools in the municipality of Prishtina. Thesis 2020, 9, 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Docker, J.G.; Fraser, B.J.; Fisher, D.L. Differences in the psychosocial work environment of different types of schools. J. Res. Child. Educ. 1989, 4, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, G.A.; Carlisle, C.; Riley, M.; Tapper, J.; Dewey, M. The work environment scale: A comparison of British and North American nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 1992, 17, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, S.; Zafar, A. China Pakistan economic corridor: Importance and challenges for Pakistan and China. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Econ. Res. 2017, 2, 511–528. [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz, A.; Su, X.; Nasir, I.M. BIM Adoption and its impact on planning and scheduling influencing mega plan projects-(CPEC-) quantitative approach. Complexity 2021, 2021, 8818296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K. Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadersh. Q. 2006, 17, 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihelic, K.K.; Lipicnik, B.; Tekavcic, M. Ethical leadership. Int. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2010, 14, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K.; Harrison, D.A. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 2005, 97, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevino, L.K.; Brown, M.E. Managing to be ethical: Debunking five business ethics myths. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2004, 18, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.J. Ethics: The tone at the top. Strateg. Financ. 1990, 71, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Hitt, W.D. Ethics and Leadership; Battelle Press: Columbus, OH, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.; Walters, R.H. Social Learning Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1986, 4, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G.; Mahsud, R.; Hassan, S.; Prussia, G.E. An improved measure of ethical leadership. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2013, 20, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D.M.; Aquino, K.; Greenbaum, R.L.; Kuenzi, M. Who displays ethical leadership, and why does it matter? An examination of antecedents and consequences of ethical leadership. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanjundeswaraswamy, T.; Swamy, D.R. Review of literature on quality of worklife. Int. J. Qual. Res. 2013, 7, 201–214. [Google Scholar]

- Hackman, J.R. Work redesign and motivation. Prof. Psychol. 1980, 11, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hian, C.C.; Einstein, W.O. Quality of work life (QWL): What can Unions Do? SAM Adv. Manag. J. 1990, 55, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, N.; Mahmood, A.; Ibtasam, M.; Murtaza, S.A.; Iqbal, N.; Molnár, E. The psychology of resistance to change: The antidotal effect of organizational justice, support and leader-member exchange. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 678952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutknecht, D.B.; Miller, J.R. The Organizational and Human Resources Sourcebook; University Press of America: Lanham, MD, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta, M.; Gupta, R.K. Innovation in organizations: A review of the role of organizational learning and knowledge management. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2009, 10, 203–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E.H. Coming to a new awareness of organizational culture. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1984, 25, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dhamija, P.; Gupta, S.; Bag, S. Measuring of job satisfaction: The use of quality of work life factors. Benchmarking 2019, 26, 871–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmiel, N.; Fraccaroli, F.; Sverke, M. An Introduction to Work and Organizational Psychology: An International Perspective; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Diriwaechter, P.; Shvartsman, E. The anticipation and adaptation effects of intra-and interpersonal wage changes on job satisfaction. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2018, 146, 116–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, R.; Di, Y.; Ramanathan, U. Moderating roles of customer characteristics on the link between service factors and satisfaction in a buffet restaurant. Benchmarking 2016, 23, 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Rangnekar, S.; Bamel, U. Workplace flexibility dimensions as enablers of organizational citizenship behavior. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2016, 17, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, D.C.; Boswell, C.; Opton, L.; Franco, L.; Meriwether, C. Engagement, empowerment, and job satisfaction before implementing an academic model of shared governance. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2018, 41, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avey, J.B.; Reichard, R.J.; Luthans, F.; Mhatre, K.H. Meta-analysis of the impact of positive psychological capital on employee attitudes, behaviors, and performance. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2011, 22, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svendsen, M.; Seljeseth, I.; Ernes, K.O. Ethical Leadership and Prohibitive Voice—The Role of Leadership and Organisational Identification. J. Values-Based Leadersh. 2020, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X. Ethical leadership and organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating roles of cognitive and affective trust. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2014, 42, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, P.; Story, J. Ethical leadership and reputation: Combined indirect effects on organizational deviance. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Zhu, W.; Zheng, X. Procedural justice and employee engagement: Roles of organizational identification and moral identity centrality. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 122, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suifan, T.S.; Diab, H.; Alhyari, S.; Sweis, R.J. Does ethical leadership reduce turnover intention? The mediating effects of psychological empowerment and organizational identification. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2020, 30, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işik, A.N. Ethical leadership and school effectiveness: The mediating roles of affective commitment and job satisfaction. Int. J. Educ. Leadersh. Manag. 2020, 8, 60–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangwal, D.; Tiwari, P. Workplace environment, employee satisfaction and intent to stay. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfiyah, N.; Riyanto, S. The Effect of Compensation, Work Environment and Training on Employees’ Performance of Politeknik LP3I Jakarta. Work 2019, 2, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Zafar, S.; Zafar, U. Nexuses between induction training and employee job satisfaction: Exploring the moderating role of organizational culture and motivation. Int. J. Bus. Financ. Manag. Res. 2019, 7, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.C.; Mai, Q.; Tsai, S.B.; Dai, Y. An empirical study on the organizational trust, employee-organization relationship and innovative behavior from the integrated perspective of social exchange and organizational sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Zafar, M.A. Impact of psychological contract fulfillment on organizational citizenship behavior: Mediating role of perceived organizational support. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1001–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natasya, N.S.; Awaluddin, R. The Effect of Quality of Work Life, Organizational Culture and Job Satisfaction on Employee Engagement. Bina Bangsa Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2021, 1, 158–165. [Google Scholar]

- Astuti, J.P.; Soliha, E. The Effect of Quality of Work Life and Organizational Commitment on Performance with Moderation of Organizational Culture: Study on Public Health Center Puskesmas in Gabus District. Int. J. Soc. Manag. Stud. 2021, 2, 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Özgenel, M. The Effect of Quality of Life Work on Organizational Commitment: A Comparative Analysis on School Administrators and Teachers. Ilkogr. Online 2021, 20, 129–144. [Google Scholar]

- Sumarsi, S.; Rizal, A. The Effect of Competence and Quality of Work Life on Organizational Citizenship Behavior (Ocb) with Organizational Commitment Mediation: Study on Jaken and Jakenan Health Center Employees. Int. J. Soc. Manag. Stud. 2021, 2, 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Azhmy, M.F.; Nahrisah, E.; Setiawan, T. Efforts to Improve Employee Performance through Quality of Work-Life and Effectively Moderated Teamwork Communication on Pt. Rajawali Property Mandiri Medan. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Manag. 2022, 3, 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, A.; White, G.R.; Thomas, B. An Extended Stage Model for Assessing Yemeni Smes’ E-Business Adoption’. In Creating Entrepreneurial Space: Talking Through Multi-Voices, Reflections on Emerging Debates; Contemporary Issues in Entrepreneurship Research; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bradford, UK, 2019; Volume 9B, pp. 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hislop, D.; Bosua, R.; Helms, R. Knowledge Management in Organizations: A Critical Introduction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Salloum, S.A.; Al-Emran, M.; Shaalan, K.; Tarhini, A. Factors affecting the E-learning acceptance: A case study from UAE. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2019, 24, 509–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Lessons for guidelines from the diffusion of innovations. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Improv. 1995, 21, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alos-Simo, L.; Verdu-Jover, A.J.; Gomez-Gras, J.M. How transformational leadership facilitates e-business adoption. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 382–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellacci, F.; Viñas-Bardolet, C. Internet use and job satisfaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 90, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, G.; Schulhofer-Wohl, S. The changing (dis-) utility of work. J. Econ. Perspect. 2018, 32, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gama, N.; McKenna, S.; Peticca-Harris, A. Ethics and HRM: Theoretical and conceptual analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, A.S. Applying the theory of planned behavior to explain marketing managers’ perspectives on sustainable marketing. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2010, 22, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Efraty, D.; Siegel, P.; Lee, D.-J. A new measure of quality of work life (QWL) based on need satisfaction and spillover theories. Soc. Indic. Res. 2001, 55, 241–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubinsky, A.J.; Hartley, S.W. A path-analytic study of a model of salesperson performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1986, 14, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, L.W.; Steers, R.M.; Mowday, R.T.; Boulian, P.V. Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians. J. Appl. Psychol. 1974, 59, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, B.J.; Kohli, A.K. Market orientation: Antecedents and consequences. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Smith, D.; Reams, R.; Hair, J.F., Jr. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): A useful tool for family business researchers. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2014, 5, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbach, N.; Ahlemann, F. Structural Equation Modeling in Information Systems Research using Partial Least Squares. J. Inf. Technol. Theory Appl. 2010, 11, 5–40. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Thousand Oakes, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelen, M.M.; van Dulmen, S.; Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M.W.; Adriaansen, M.J.; Vermeulen, H.; Bredie, S.J.; van Gaal, B.G. Self-management support in cardiovascular consultations by advanced practice nurses trained in motivational interviewing: An observational study. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, R.; bin Mohamed, N.A. Development and validation of an instrument for multidimensional top management support. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2017, 66, 873–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, S.A.; Hinton, D.P.; Fraccaroli, F.; Sverke, M. What do people really do at work? Job analysis and design. In An Introduction to Work and Organizational Psychology: An International Perspective; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 396 | 65.0 | 65.0 | 65.0 |

| Female | 213 | 35.0 | 35.0 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 609 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Marital Status | Single | 126 | 20.7 | 20.7 | 20.7 |

| Married | 483 | 79.3 | 79.3 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 609 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Age (Years) | 21–30 | 184 | 30.2 | 30.2 | 30.2 |

| 31–40 | 323 | 53.0 | 53.0 | 83.3 | |

| 41–50 | 79 | 13.0 | 13.0 | 96.2 | |

| 51–60 | 14 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 98.5 | |

| 61 & above | 9 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 609 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Education Level | Bachelors | 93 | 15.3 | 15.3 | 15.3 |

| Masters | 342 | 56.2 | 56.2 | 71.4 | |

| M.Phil. | 124 | 20.4 | 20.4 | 91.8 | |

| Ph.D. | 43 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 98.9 | |

| Others | 7 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 609 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Monthly Income (In Thousand PKR) | 20–50 | 172 | 28.2 | 28.2 | 28.2 |

| 51–80 | 132 | 21.7 | 21.7 | 49.9 | |

| 81–110 | 204 | 33.5 | 33.5 | 83.4 | |

| 111–140 | 94 | 15.4 | 15.4 | 98.9 | |

| 141 & above | 7 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 609 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Dev. | Coef. Var. | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EL | 609 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.5480 | 0.84586 | 4.1945 | −1.191 | 1.026 |

| REL | 609 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.3437 | 0.91151 | 3.6683 | −0.419 | −0.339 |

| SMC | 609 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.6489 | 0.85405 | 4.2725 | −1.690 | 2.514 |

| QWL | 609 | 1.00 | 4.92 | 3.4068 | 0.74305 | 4.5849 | −1.482 | 2.891 |

| ICT | 609 | 1.50 | 5.00 | 3.6770 | 0.88643 | 4.1481 | −0.740 | 0.134 |

| JS | 609 | 2.00 | 5.00 | 4.1698 | 0.53338 | 7.8177 | −0.311 | 0.689 |

| OC | 609 | 2.00 | 5.00 | 3.8333 | 0.67183 | 5.7058 | −0.299 | 0.015 |

| TS | 609 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.6480 | 0.70181 | 5.1980 | −0.443 | 0.639 |

| α Values | AVE | MSV | MaxR(H) | QWL | EL | OC | TS | ICT | JS | REL | PG | SMC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QWL | 0.772 | 0.651 | 0.481 | 0.962 | 0.807 | ||||||||

| EL | 0.870 | 0.615 | 0.510 | 0.961 | 0.694 *** | 0.784 | |||||||

| OC | 0.829 | 0.768 | 0.354 | 0.981 | 0.588 *** | 0.500 *** | 0.877 | ||||||

| TS | 0.759 | 0.716 | 0.312 | 0.953 | 0.429 *** | 0.356 *** | 0.492 *** | 0.846 | |||||

| ICT | 0.736 | 0.752 | 0.379 | 0.949 | 0.615 *** | 0.447 *** | 0.465 *** | 0.395 *** | 0.867 | ||||

| JS | 0.810 | 0.862 | 0.418 | 0.974 | 0.646 *** | 0.526 *** | 0.570 *** | 0.558 *** | 0.583 *** | 0.928 | |||

| REL | 0.744 | 0.791 | 0.480 | 0.950 | 0.693 *** | 0.685 *** | 0.529 *** | 0.406 *** | 0.562 *** | 0.581 *** | 0.890 | ||

| PG | 0.814 | 0.708 | 0.455 | 0.880 | 0.624 *** | 0.675 *** | 0.409 *** | 0.345 *** | 0.414 *** | 0.394 *** | 0.600 *** | 0.842 | |

| SMC | 0.792 | 0.811 | 0.510 | 0.932 | 0.693 *** | 0.714 *** | 0.595 *** | 0.400 *** | 0.471 *** | 0.566 *** | 0.620 *** | 0.501 *** | 0.900 |

| EL | OC | TS | ICT | JS | REL | PG | SMC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QWL | ||||||||

| EL | 0.705 | |||||||

| OC | 0.581 | 0.497 | ||||||

| TS | 0.403 | 0.343 | 0.469 | |||||

| ICT | 0.619 | 0.451 | 0.461 | 0.394 | ||||

| JS | 0.642 | 0.526 | 0.552 | 0.539 | 0.591 | |||

| REL | 0.701 | 0.708 | 0.527 | 0.401 | 0.565 | 0.587 | ||

| PG | 0.619 | 0.673 | 0.404 | 0.333 | 0.415 | 0.392 | 0.608 | |

| SMC | 0.697 | 0.731 | 0.586 | 0.388 | 0.473 | 0.557 | 0.633 | 0.507 |

| Model | RMR | GFI | AGFI | PGFI |

| Default model | 0.038 | 0.757 | 0.738 | 0.702 |

| Saturated model | 0.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Independence model | 0.426 | 0.066 | 0.039 | 0.065 |

| Sr. No. | Hypotheses | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | Rel <--- EL | 0.717 | 0.046 | 15.593 | *** |

| H1b | PG <--- EL | 0.832 | 0.048 | 17.349 | *** |

| H1c | SMC <--- EL | 0.728 | 0.042 | 17.428 | *** |

| H2a | QWL <--- Rel | 0.179 | 0.037 | 4.819 | *** |

| H2b | QWL <--- PG | 0.283 | 0.035 | 8.102 | *** |

| H2c | QWL <--- SMC | 0.284 | 0.036 | 7.888 | *** |

| H3 | QWL <--- EL | 0.118 | 0.055 | 2.155 | 0.031 |

| H4a | JS <--- QWL | 0.559 | 0.033 | 17.122 | *** |

| H4b | OC <--- QWL | 0.535 | 0.036 | 14.827 | *** |

| H4c | TS <--- QWL | 0.372 | 0.035 | 10.492 | *** |

| Path | R | R-sq | MSE | F | |

| H5a | ICT.Skil. Mod Job.Sat. | 0.2314 | 0.0536 | 0.2706 | 11.4106 |

| H5b | ICT.Skil. Mod Org.Comm. | 0.1638 | 0.0268 | 0.4414 | 5.5605 |

| H5c | ICT.Skil. Mod Team Spir. | 0.1640 | 0.0269 | 0.4817 | 5.5729 |

| Indirect Path | Unstandardized Estimate | Lower | Upper | p-Value | Standardized Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EL --> Rel --> QWL --> JS | 0.072 | 0.046 | 0.102 | 0.001 | 0.134 *** |

| EL --> Rel --> QWL --> OC | 0.069 | 0.044 | 0.097 | 0.001 | 0.134 *** |

| EL --> Rel --> QWL --> TS | 0.048 | 0.030 | 0.071 | 0.000 | 0.134 *** |

| EL --> PG --> QWL --> JS | 0.132 | 0.088 | 0.183 | 0.001 | 0.246 *** |

| EL --> PG --> QWL --> OC | 0.126 | 0.088 | 0.175 | 0.000 | 0.246 *** |

| EL --> PG --> QWL --> TS | 0.088 | 0.059 | 0.125 | 0.000 | 0.246 *** |

| EL --> SMC --> QWL --> JS | 0.115 | 0.077 | 0.160 | 0.001 | 0.216 *** |

| EL --> SMC --> QWL --> OC | 0.110 | 0.074 | 0.151 | 0.001 | 0.216 ** |

| EL --> SMC --> QWL --> TS | 0.077 | 0.052 | 0.111 | 0.001 | 0.216 *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khan, M.; Mahmood, A.; Shoaib, M. Role of Ethical Leadership in Improving Employee Outcomes through the Work Environment, Work-Life Quality and ICT Skills: A Setting of China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141711055

Khan M, Mahmood A, Shoaib M. Role of Ethical Leadership in Improving Employee Outcomes through the Work Environment, Work-Life Quality and ICT Skills: A Setting of China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Sustainability. 2022; 14(17):11055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141711055

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhan, Maria, Asif Mahmood, and Muhammad Shoaib. 2022. "Role of Ethical Leadership in Improving Employee Outcomes through the Work Environment, Work-Life Quality and ICT Skills: A Setting of China-Pakistan Economic Corridor" Sustainability 14, no. 17: 11055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141711055

APA StyleKhan, M., Mahmood, A., & Shoaib, M. (2022). Role of Ethical Leadership in Improving Employee Outcomes through the Work Environment, Work-Life Quality and ICT Skills: A Setting of China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Sustainability, 14(17), 11055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141711055