1. Introduction: A Special Methodological Framework of Theoretical Focus

Albert-László Barabási in his book called “

Linked: The New Science of Networks” [

1] gives a detailed analysis of the birth and operation of networks that infiltrate all areas of human life and are almost organically growing. (Networking is seen by the authors of this paper as an organisational model defining the basic structure of existence, similar to the interpretation of disability and accessibility by the authors. Man providing accessibility can partially compensate for his adaptation deficiencies by organising into networks, but this does not exempt him from his existential disability.) Since the publication of Barabási’s book, several essays have appeared on the topic, and the author himself has deepened and further contemplated his own and his research team’s statements, considering the paradigm of networking suitable for integration with almost all fields of science (including travel science). However, statements concerning philosophy, especially existential (life) philosophy and Buddhist philosophy can only be seen indirect ways in the related literature and research. This endeavour is implemented by the authors by giving up the standard linear flow of their trains of thoughts, which characterises the major part of current academic and philosophical discussions. It must be remarked that the first author of the paper, a philosopher, was born with a locomotory disability and must use a wheelchair, and, accordingly, possesses in-depth knowledge and experiences concerning accessibility which, although are not a substitute for primary research, provides a meaningful contribution to the theoretical and philosophical character of the paper, which hopefully is respected by the academic community. This state is the consequence of the transformation of the nervous system, which also impacts his abilities to acquire and practice writing and reading skills. Furthermore, these facts also justify the partial differences from the mainstream of philosophy and conceptualising ways and methods—e.g., oral-centredness—as a root of his personalised knowledge acquisition methods. He and author 2 of this article have been studying for years the touristic, philosophical, (meta)theoretical and practical implications of accessibility, including research on the topic of networking. This paper is a phase of this joint work, written as a special case study, in order to prove, among other things, that tourism science and travel management, in the practical sense, can gain relevant and positive benefits from the integration of the intellectual toolbox of philosophical dimensions. In this special case, the necessary continuous recreation of more direct connection to reality behind the datasets of empirically minded management science “dimensions” can be assisted by the scrutiny and interpretation method continuously developed by the authors.

This paper is a brief attempt to broadly outline the Buddhist and life philosophy interpretation frameworks of networks and cooperations, and their connections to travel science and to address accessibility issues, connected to the central message of the paper by three of the present authors called “

Fundamental accessibility and technical accessibility in travels—the encounter of two worlds which leads to a paradigm shift:

the new paradigm of fundamental accessibility” [

2]. The authors’ goal then is clearly to make a contribution—however modest this may be—by the specific philosophical scrutiny “methodology” of the paper, to the never-ending and self-fertilising discourses of scholasticism and the academic community. It is enough to mention that the analytic method of emptiness philosophy, also playing an important role in this paper—revealing mutual presumption in the existence of all entities—shows similarities, surprising for many scholars, to the basic principles of quantum physics and the empirical research findings verifying these [

3,

4]. Accordingly, we believe that both travel science and the paradigm of accessibility can profit significantly from the findings of this special philosophical—hermeneutical—means of analysis, mostly through the enlargement of the mainstream and accepted methodology of empirical research by the holistic theoretical approaches briefly outlined by the authors. The present paper is meant, on the one hand, to deepen the correlations among the existing pieces of knowledge, and to make, on the other hand, further steps towards the creation of a sovereign accessibility paradigm. This is conducted by choosing a scrutiny method that is definitely theoretical—philosophical-hermeneutical examinations—but of course also containing facts and figures from the world of travel science in order to present the academic foundations of the statements, as the dimension of travel researchers has been the receiver and carrier of this life and Buddhist philosophy approach for years. In this paper, this approach is called philoscophic.

The way this endeavour should be realised is to give up the traditional linear approach of the trains of thoughts that are typical in most contemporary academic and philosophical papers, i.e., the “research methodology” of the authors’ philosophy is of a philoscophic character, which refers to the application of existing knowledge, its placement in a new context and the birth of new interconnections, on the one hand; on the other hand, it draws attention to the reconsideration of thinking and, in close correlation with this, of concepts, to the process character of creation, and to the discovery of all these over and over again. Accordingly, the texts by the cited philosophers and thinkers are seen as thoughts that come alive through the discourse, in a “dialogue” with the philosophers referred to [

5]. This, on the one hand, is a reference to the philosophy “model” of networks by Deleuze [

6], which is built on more than one single centre, and also, on the other hand, to the fundamental objective of Gadamer’s hermeneutics that means, in the first place, the “animation”, and the application of texts that we read [

7]. The latter can be realised, in the interpretation and practice of the German philosopher, through an intellectual dialogue with the author. This means that Gadamer’s emphasis is not on the didactic processing of texts, so fragmented components of thoughts may not necessarily follow each other closely in the text. The main objective by using this wording method is to encourage readers to step out of the conventional frameworks provided by the mainstream interpretation of concepts and thematic collections used in tourism science. The target group of the academic audience and other interested parties are encouraged to move closer to the typically holistic life-interpretation and world-view-creating objective of philosophy, and to further contemplate the present positions of tourism science and their personal attitude in these. Several papers published in acknowledged Hungarian and international periodicals directly used this kind of attitude [

8,

9,

10,

11], typically in multi- and interdisciplinary frameworks, measuring its inspiring impact of life and Buddhist philosophy on science.

It must be remarked that “total” methodological coherence that is expected of the mainstream academic publications (alignment of theoretical and empirical research parts) is not feasible and is not a goal, either, in this special amalgamation of philosophy and tourism, bearing specific synergies. For this reason, it was not a goal of the authors to reconcile the different concept interpretations and theories of the philosophical/empirical scrutiny and the tourism analyses focusing on empirical surveys.

Tuning back to the train of thoughts of life philosophy scrutiny, the thoughts of Mihály Babits are borrowed. Babits—who is an excellent expert of the philosophy of Bergson—says the following about the relationship between reading and thinking:

“I think it would be good if our philosophers were reading less and thinking more. Nietzsche said in one of his university lectures that the most effective way to destroy originality is to spend every free minute we have with a book in our hands. The scientists of our time are really reading machines: As if all rubbish that in this world is pressed, All that flimflam should be filled in their heads.” [

12].

This brief essay is meant to be an aid to assisting thinking about the seemingly non-interconnectable fields of accessibility, disability and networking. It is evoking flows of thoughts and the mapping of their depths that the authors wish to achieve with their paper. This means that the readers should not expect the working of exact final conclusions; the creation of these conclusions is left to the readers, provided that they feel it is necessary, together with the task of discovering the accessibility-promoting or accessibility-hindering nature of networking.

2. The Nature of Networks Describing, Mapping and Altering the World of Life

It is well-known now that travelling has become a mass phenomenon. Researchers who pay attention to more in-depth study of this process also know that one generator of this is the considerable change of both socio-economic and technical conditions [

13].

This discussion is meant to shed more light on the researched but less preferred approach without which travels could not have become a driving sector of the economy and thus the science of travelling could not have become a discipline on its own. This essay is actually about the life philosophical analytics of networking, and of the necessity of technical accessibility that is a fundamental element of networking.

It is obvious that today’s travellers organise their “discoveries” right from the birth of the travel intention to the moment of getting back home on the World Wide Web, with the help of the internet. What is more, the communication platform of their experiences—and their lives, actually—is now the information superhighway (Extremely complex research has been implemented in recent years, and is still continuing, in different fields of academic life, including think-tanks of communication researchers, concerning why people choose social media platforms as a scene for living their impressions and adventures [

14].

It is not an accident that the authors’ phrasing makes a distinction between the internet and the World Wide Web, two concepts that are often blurred and treated as synonyms. As Barabási implies, the two are not the same [

15]: internet is a network where computers are physically linked to each other, whereas the World Wide Web is a much more complex network of information flow and transportation that is continuously expanding and growing. This is a distinction that we must remark is of utmost importance, as it projects a content of fundamental significance for the following train of thought.

The birth of the World Wide Web and its integration into the fabric of life at astonishing speed is now transforming our whole

world. On the one hand, it lures digital wanderers with the illusion of limitlessness; on the other hand, it is also capable of confining them into a kind of cyber-prison [

16,

17]. The walls and bars of this prison, however, can be found not in the world outside, rather in the inner world permanently besieged by the avalanche of stimuli on the conscious [

8,

9].

The paper is also meant to draw the readers’ attention to the fact that the expression

our world covers, in this case, the total of human beings living on the planet, with no intention to express either a Western orientation or a Europe-centred attitude. Accordingly, in the case of disability and accessibility as

network specificity discussed in the next subchapter, we will see that the differences between the discussions of these two concepts in the so-called Western and the Buddhist philosophy approach seem to be non-interconnectable at first glance, but the situation is not that clear-cut by far [

17,

18].

Networks, as they are known, are not exclusively man-made “beings”; life itself defined by the tools of biology can also be described as the

result of processes going on in the complicated fabric of networks [

19].

One of the significant philosophy efforts, in other words, network junctions of the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, is the wording of a system of thinking in which being or life—used as a synonym of the former—resembles a plant in constant change, without central roots, where the prerequisite of the self-sustenance of the organism is cooperation among the isolable junctions. Not one of these “nervous centres”, however, has a central role elevating it above its peers [

20].

The model by Deleuze is basically built on the philosophy of Bergson inasmuch as how man’s existence watching and shaping the world—i.e., the potential role of man, as part of the system—can be interpreted and how they can change maybe from one moment to the other [

21]. The survey methods of human activity shaping and contemplating the world are, at the same time, the limits of the freedom of will, quite paradoxically in our opinion. This paradox can be solved by keeping the capability of remembrance, or its re-acquisition, alive. Bergson’s intuitive view and practice also entails the acquisition of the ability to immerse into the dimensions of remembrance. This gives man a real freedom of will and action, as bringing memories to the conscious level serves as a signpost for shaping and re-discovering the present [

5]. Accordingly, the organisational structure of Deleuze’s world view, void of central points, is similar to Bergson’s intuitive method, which does not link the knowledge of life to exact quality levels [

22,

23].

A quasi-natural interface to this philosophy trend and “methodology” is the thought of an essay by Frigyes Karinthy (a Hungarian author, playwright, poet, journalist, and translator, the first proponent of the six degrees of separation concept in his 1929 short story, Chains, i.e., “Láncszemek”), considered as a basic work by Barabási. In this, the writer-philosopher—known and recognised internationally—proves in an intuitive way that it takes not more than five personal relationships to connect any person of the world’s population of the time (approximately one-and-a-half billion people) to another one [

1]. The network model “envisioned” by Karinthy can even be used as a motto of travel science, considering that the desire of people to contact each other and get to know the world is even stronger today than it was in the 1920s, and the conditions that have allowed tourism to become a real mass phenomenon have been created by now. These factors are technical conditions increasingly organised into networks (travel devices and infrastructure), and the organisational background (the total of the tourism industry with tour operators, accommodations etc.). The brilliant thoughts of the intuitive intelligence of the Hungarian writer were empirically verified and proved at almost the same time as the theory of networks became an academic discipline.

The dominant feature in the series of contemporary network paradigms may be scale independence. This means that the networks organised randomly, a theory created by two other Hungarian mathematicians, Alfréd Rényi and Pál Erdős in the 1960s, has been replaced by networks organised by the principle of scale independence, i.e., according to the new model, the “partial units” making the networks are organised around selected junctions.

An approach of this kind to the operation of scale-independent networks of course leaves a lot to be desired, should one read these lines through the “spectacles” of a network research expert. This paper is based on a scrutiny of philosophical focus, it was, however, not written primarily for readers with an interest in network science; nevertheless, the authors are happy to receive any critical remark or recommendation that further deepens the infinite network maps of their philosophy scrutinies.

These centres are the carriers of information, also operating as gravity centres, i.e., randomness can be excluded as a fundamental and self-standing principle of the organisation of networks. When projecting the previously discussed method to the world of travelling, it becomes clear that we are possessors of information, whether we want it or not, but they also influence all those potential clients who, for orientation reasons, for example, seek a business offering catering for them to be accepted in a foreign country. These can be defined as manifested junctions in a network structure. The number of the interconnections that e.g., a traditional restaurant can generate is dependant primarily on to what extent it is integrated into a broader network structure.

This is, “in a nutshell”, the interfaces of networks, travel science and life philosophy. The next chapter is a detailed analysis of the philosophy approach to barrier dismantling and generation, also mentioned in the preface, not moving beyond the multidisciplinary frameworks of the world of travelling.

About the Dangers of the Barrier-Generating Nature of Barrier Dismantling

Technical accessibility (i.e., breaking down barriers) is usually defined as exact activities having a positive impact on our lives, implemented especially for people living with disabilities [

8,

10,

23].

The expansion of these interpretation framework and dimensions—with the aspects of life philosophy and hermeneutics—has considerable implications also for the areas of both networks, and accessibility and disability.

The following (at first glance, possibly strange) analysis and way of interpretation, based on hermeneutics but basically of life philosophy nature, may seem completely alien to the science of travelling, but the authors are convinced that they can prove its raison d’étre.

Let us call attention to the debate that reached its peak in the late 19th and early 20th century when philosophies started a kind of specialisation; to put it simply, special “branches” of philosophy were born. Against this process protested Martin Heidegger [

24] and Karl Jaspers [

25] and—in a specific way—Mihály Babits [

12]. The two German philosophers—similarly to several of their contemporaries of the European continents who cannot be mentioned here for lack of space—considered the effort hallmarked by the name of Husserl, i.e., the effort to define and acknowledge philosophy as strict science discipline, as a drastic “shackling” of philosophy.

As regards to the viewpoint of the authors, they also make their stand for the “pure philosophy approach” by Heidegger and Jaspers, even though it is just the basis on which they try to prove that life philosophy can now hold its own in the world of science—in a way that neither its own identity nor the conditions of the objectivity of “scientificity” are disabled.

Let us start from the hypothesis that understanding the organisation and operation of networks, and its character now infiltrating into our existence makes us navigate more easily in the world that surrounds us. In fact, or as an activity of teleological character can be more accurate, at least this is one interpretation of the activity of experts specialised in the research of networks [

15].

What the authors say after this is that what a

man creating technical accessibility, who seems to forget the spirit of fundamental accessibility, does is searching the barriers existing in the world with his research, creating mostly data-based systems [

26,

27], and thereby generating constantly appearing factors that inhibit his own self.

Let us look at the ever-more-complicated nature of the network character of air transportation that is now the backbone of the world of travel and actually allows displacement in any direction of the surface of the planet. Barabási justifies in his book, papers and in his academic presentation accessible by the cited internet address [

28], the academic relevance of the scale-independent organisational model just through the analysis of the network of air transportation. In addition, he specifies the implementation of the “scale-independency” model as one of the reasons for the exponential growth in the sector—which has been affected by the great economic crisis emerging from the very beginning, but the real “drop” occurred in 2020, due to the measures made to harness the COVID-19 pandemic; highlighting the dependent nature of any network structure, the plethora of bottlenecks over which we basically do not have any control [

29] (

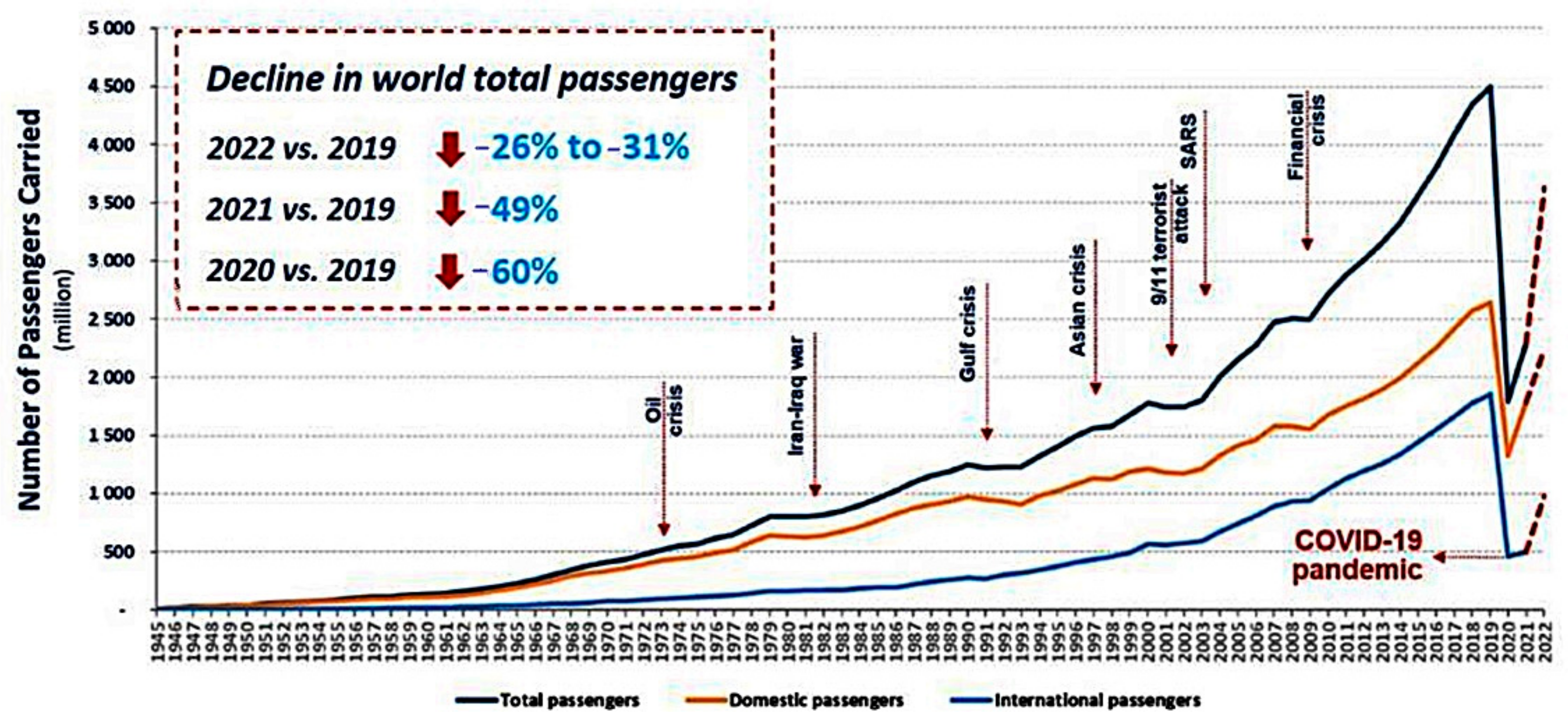

Figure 1).

Being aware of the astonishing volume of the impact of residential, economic and political, etc. circumstances [

30], the authors came to the following conclusions: the development of information technology and automation, growing apace, is not followed by the development and implementation of the ideal of environment consciousness at a similar speed.

The exponentially growing “free radicals” of the “mega airports” with extreme importance in the outlined network models—by which authors mean connection points through which the smaller capacity airports are accessible—are also the most vulnerable points in the networks. Just think of the eruption of the Eyjafjallajökull volcano in Iceland in 2010, which paralysed air transportation in a large part of Europe, clearly indicating the

vulnerability of the central airports; and the shutdowns initiated as an effect of the COVID-19 pandemics in 2020 practically eliminated the chance of free travel (the foundation of tourism) in the larger part of the world, resulting in a hopeless situation for those points in the network that were solely specialised in the service of tourists [

31,

32].

In the interpretation of the authors then, these junctions create at least as many barriers in the world as the many obstacles they break down for us. The authors believe that the emptiness philosophy and hermeneutics interpretations discussed in more detail below support their statements of empirical character. The notion of scale-independent network structures is not a solution by far for all situations, because, as it has been demonstrated, in certain situations it might decrease the exposure of some destinations to different unwanted events, but these network structures are in the best case hibernated, or in the worst case, disintegrated by a major (in this case, global) crisis. The goal in the philosophical reading, seeing the lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic, is to have reactions given to crises moving towards hibernation, by the better and better, never-ending process approach to scale-independent network structures and “organisms”, so that the collapse of these systems can be better avoided. There are evident experiments, and efforts, for example, for the promotion of domestic tourism parallel to the weakening of the pandemic [

33], or even for the subsidisation of the wages of those employed in tourism by the state. However, the global fright behind the COVID-19 pandemic and the fear of collapse simply did not allow the so badly desired scientific reality, and humanity in the broadest sense of the word, to be widely accepted by decision-makers, even if the modes of anxiety for the society and the self-lying behind these measures are acknowledged and respected. For this reason, the authors suggest—and hopefully have made it visible in the lines above—the application of a process-oriented approach and scrutiny medium, as opposed to the static concept and the static view of interpreting the world [

34,

35].

This is not only a characteristic feature of the interpretation dimensions of philosophy, it can also be extended to all physical and intellectual dimensions of existence. A still-unanswered question of the discussions of philosophical interpretations is whether the ways of networking that have been justified by exact mathematical methods can also be described with ontological or epistemological concepts. The process view that has just been mentioned can be seen as a bridging solution in the authors’ opinion, although not for the final decision on the issue—which, anyway, cannot be a realistic expectation, just because of the flow character determining the view of existence—but it can be a good starting point to at least neutralise the opposition considered as insoluble between the two philosophical “methodologies”. Thus, the research on the “physiology” of networks is an epistemological work, on the one hand, and also an ontological scrutiny, on the other. It is epistemological in the sense that the organoleptically palpable transitions of the physical implementation of travel and the technological development directions of these are philosophically analysed. Just think about the increasingly widespread methods of the digitalised processing of air transport corridors and junctions which open up new horizons for both travellers and researchers. It is also ontological, on the other hand, in the sense that the interpretation analytics of the visualised models in up to three dimensions covers an organic character invisible to the eye.

In the philosophy of modern times, it is especially Bergson who considered immersion into the subject of the scrutiny as a basic condition—it must be remarked that this method was not alien to the concepts of Jaspers, either [

36]—so as to possess information that is an irreplaceable prerequisite of either our later empirical research or our conclusions. In other words, without ontological skills, an “existential fragment”, objects, but even abstract notions are unrecognisable [

22]. This method is an alternative reading of the above-mentioned philosophical intuition. This might make more comprehensible a statement by Deleuze who said that the philosophical intuition by Bergson is one of the most sophisticated, mature “methodologies” of western philosophy, as regards to its elaboration and applicability [

6].

Ropolyi [

37], in his essay written on techno-science and philosophy science, uses a similar method as the authors of this essay do when trying to solve the opposition of ontology and epistemology. They believe that the methodology of network science, and even more so, its statements applicable in our everyday lives, implicitly involve this neutralising intention. We, the ones who, immersing into the world of travel and, in the best case, becoming identical with it, rise to the surface repeatedly, and experience both the existence of these networks during this travel of ours, and its positive and less useful direct impacts. In other words, we can see our own work and findings as ever-recurring justifications of our barrier-dismantling human character.

In order to more efficiently highlight and support the philosophical meaning and statements of the paper, the next chapter guides the reader to the network-viewed world of Buddhist philosophy—a philosophy whose origin goes back to more than 2500 years, following the strict teaching of the Buddha. Accordingly, we would not be able, even if we wanted, to provide a complete picture, if you like, of a networking scheme, all the authors are doing is reviewing philosophy beyond the Western-centred philosophy standards, exempt from the aspects of hierarchy.

3. Travelling around Me, Us and the Personality, Following the Teaching of the Buddha

It has been mentioned in the previous chapter that the view of life and the world that it has been organised into, and describable by networks, can be traced back up to thousands of years into the history of mankind. As it has also been raised, the science of networks now maps ever-more deeply existential dimensions more closely or loosely cooperating with each other.

This chapter invites readers to make a daring discovery, taking the risk of walking in the shoes of a traveller of whom travel organisers expect unconditional trust, at the same time assuring him that he will not be exposed to physical danger but will be led through an intellectually adventurous journey straining his knowledge. The authors hope that this will lead to meeting several of their goals, i.e., they will be able to provide good examples for conscious travel organisation and thereby for experience-processing [

38].

The authors wish to expand the interpretation ranges of travel, called beatific by Michalkó, as this excellent researcher tells us: travel will make us happy only if we actively—that is: consciously—act like this [

39].

If we recall the diagram in the previous chapter—demonstrating the volumes and affiliation of passengers participating in air transportation—we can see that the amount of travel from Europe and North America still prevails, but this tendency is slowly turned around by the increasing travel intentions of our fellows who live in Asia. The authors of this paper do not only see the individuals making the diagrams and numbers; they try to see in each case the people behind these data series of, if you like, networks of data.

The use of the expression ‘individuals’ is not accidental; it reveals an intention to refer to the Buddhist social view to be introduced below, and to the self-image in close correlation with this. It must be remarked that the scope and focal points of this paper do not allow the detailed elaboration of these two extremely interesting approaches, all that the authors can do is to point out the main junctions of the travel with its networked nature. A reader showing a more in-depth interest in the topic can find further sophisticated thoughts about the issue in the literature cited, the books by Tibor Porosz [

40,

41] called “

A buddhista filozófia kialakulása és fejlődése a théraváda irányzatban (

The birth and development of Buddhist philosophy in the Theravāda school)” and “

Szubjektív tudomány—objektív tudás (

Subjective science—objective knowledge)”, respectively.

The teachings of the Buddha, contrary to all other beliefs, do contain statements concerning society as a natural way of co-existence, in fact, they even contain exact teachings. Unlike what is typical in the West, the Buddha does not consider as acceptable either an organicist model or one based on some kind on contract. He sees the associations of humans as their natural state that also secures their survival. The enlightened teacher mentions infants as an example: the precondition of the survival of the little child born in this world is naturally belonging to a society. The mother and the people surrounding the infant provide conditions of survival and development for the infant, without any agreement, or constraint to adapt to any hierarchy [

40].

This is coherently related to the interpretation of the personality of man and thereby his place in the world. In European culture, an individual is the intellectual product of modern times—concretely: the age of enlightenment—which in the context of this paper means the concept of a person who is able to succeed as a sovereign entity.

The philosophical approach to Buddhism says that there cannot be entities existing in total independence from each other; accordingly, the concept of man independent of everything and everyone cannot be correct, either. Even hermits leaving human civilisation behind cannot stay alive if the energy demand of their body is not supplied from their environment.

One of the most debated, or at least in the Western culture, most misunderstood teachings of the Buddha, is the world view of

selflessness or

impermanence. This description of the existential structure, derived from knowledge from experiences (Let us consider the practice-oriented “travel” of Buddhism, the main

transport tools of which are the broad range of meditation practices, i.e., knowing ourselves and the world is not restricted to either theoretical abstractions or the scientific methods of the discovery of the world. An outstanding tool of learning for Buddhist practitioners is meditation [

42]. It must be remarked though that the practical use of meditation is not alien to the religious practice of Christianity, either, for communication or intellectual unity with God [

43]), is a characteristic feature typical of all elements making the universe, all micro and macro manifestations. This state, void of permanence, may be frightening for man who constantly seeks support in the interpretation of this paper, and needs and creates tools of technical accessibility. In the authors’ opinion, this is only one of the possible readings; they are convinced that just the opposite of fright can also be experienced by looking at impermanence as a tool for getting to know existence [

34,

43]. The authors have to remark in this place that they abandoned the explicit wording of hypotheses and conclusions, which are traditional support pillars, in connection with the traditions of the interpretation of existence by Buddha. The limits of the paper do not allow, unfortunately, a more in-depth elaboration of this; a browse of the books and papers on this issue, enumerated in the list of references, allows interested readers both to reach a deeper understanding and to ask further questions. The authors find it important to remark that Buddhist philosophy, more exactly, the practice of life and the wisdom of consciousness making its foundation, are not equivalent to the concepts and implementations of philosophy or philosophising in the European or Western sense. The mutually dependent entity-interpretation modes of the already-mentioned school of emptiness philosophy (Madhyamaka), for example, are not exclusively the simply cognitive “products” of human sense, but are also “relics” of the experimental discovery journeys of Buddhist meditation, i.e., the subjective and objective personal projections of Buddhist philosophy and wisdom cannot be separated as rigidly from each other as it is demanded by the paradigms and methods of European or Western scholasticism [

44].

Accordingly, the contexts of networking, or accessibility and of travel science are becoming more expressed, even if we have to get used to their multi-dimensional and holistic character, significantly different from the mainstream, of the philosophic scrutiny method of the already-cited paper published recently by some authors of this present article in the periodical “

Sustainability” [

2]. With the “application” of this, the authors wish to inspect the basic conceptual (and life-quality-determining) manifestations of networking, accessibility and travel, in order to get to a potential and innovative concept origin explaining topology, which makes it clear that the cluster of these three concepts and sets of actions are not the fruits of the recent research findings of modern times: e.g., the Buddhist way of thinking and world discovery practice (meditation forms) actually show us the schematic maps and travel guides of their re-discovery going back thousands of years in all three cases. The figure below, borrowed from Tibor Porosz (

Figure 2), is a demonstration of the statements above and their practical academic use, i.e., the nature of emptiness in the seeming-centre of human conscience as the most appropriate research “tool” at hand, which can be basically outlined as a scale-independent network structure, also, its “operation” can also be interpreted this way [

40].

As we can see, self is not floating in the void, in fact, it is demonstrated as a kind of network centre of form, feeling, perception, conscience and urge; also, the interrelations among the “elements” are described as well. So it can be said, on the one hand, that each element is related to the others, without any hierarchical structure in this system of interrelations; on the other hand, it also models a networked intertwining of the conscience in which a kind of vibration of e.g., the processing of stimuli from the outside world, and the conscious reactions given to them, infiltrate the whole “system”. The self-image is born as a consequence of these impacts and the reactions to them, but, because the outer and the inner worlds are constantly harmonised, the role of self-generating components in the network is definitely situation-dependant.

It is absolutely evident that the outline of the conscience, the self and the body mutually presuming, creating and eroding each other can only be extremely vague in this paper. All that is indicated by this brief summary is that the presence and study of networks, even if not in the recent sense of the word, were issues already motivating thinkers millennia ago [

45,

46].

The above-described

conscience model with a networked character and operation can be extended to the concept of “conscious tour organisation, conscious travellers” increasingly in the focus of travel science these days [

38] inasmuch as it can now be applied in converting the mass of new stimuli, impacting the access to the desired destinations and acting with increasing intensity during their stay there, into real experiences.

If travellers are considered to be the network centres of travel and are linked by all points oriented towards the experiences that they got in touch with during their stay in their destination [

47], the outline of a complicated network can be seen. Each and every one of these connection points has their own impact on man, but, more importantly, they surround him as a sea of stimuli.

As we have to learn how to stay alive in water by means of swimming, we must also find our way in this medium full of stimuli. It is just the preservation of the health of our constantly changing self that necessitates the acquisition of the capability of the classification of “information” coming from the network, so as to convert them into real information giving a meaningful content without quotation marks [

5].

This is where the conceptual frameworks of the milieu outlined by Michalkó is linked to the above-described scheme of becoming conscious, because, as we know, the birth of the milieu experience is contributed to a large extent by the current state of the inner world of the traveller [

48].

The experts in the world of travel, in the authors’ opinion, must also acquire the skills by which they can assist the ever-increasing masses of travellers so that man should not only ramble as enlarging “swarms” of tourists in the global wilderness of temptations ever increasing in quantity, but become explorers as conscious travellers of both the world outside and their own inner universes.

Transfer of Knowledge, i.e., Training as an Origo for the Building up Networks

Previously, the difference between a tourist and a traveller was featured as an issue of grade, referring to an essential “theorem” of Bergson’s philosophy: the definite separation of grade and natural differences [

22]. In this context, the authors indicate that distinction between the seemingly only conceptual categories of traveller and tourist actually involves qualitative differences as well. In this closing chapter of the paper, this distinction is featured as a natural one, i.e., an actual development curve is outlined that happens in the spiritual world of man, and thus leads to connections much deeper than before to all that is existing and to existence itself.

The oppositions that seem to exist between “me” and “us” can also be interpreted as if they existed as separate networks, and points of interconnection were organised by the principle of the “laws” of randomness, only. In other words, as if the seemingly constant centre of the individual—one form of me: the ego—decided arbitrarily when it created interfaces with fellow humans around it and in what form.

The authors believe that one of the most important teachings and guidelines of Buddhist philosophy can help us solve this seemingly marked “me” and “us” dichotomy. This teaching has a dependant origination, i.e., the view that tries to prove in an understandable way that we humans are parts—builders and, in many cases, destructors at the same time—of a network bearing both ontological and epistemological features [

49].

Each activity of ours is correlated to the network junction featured in the figure below. Although it can be interpreted as a network map of the reasonable relationships of the existence of a human, the authors are convinced that it is just its complexity and spirituality that proves how much we are dependent on all existing elements and factors that surround us (

Figure 3).

We who are part of the world of the science of travels—irrespective of whether we are students, work as professors, or academics analysing data—are responsible for those people for whom travelling has become a life form by now.

Thus, as it has already been stated, the spirit of the training of experts for our discipline, tourism, must also be necessarily penetrated by the need and ability of a conscious world view and professional organisational skills. One main driver of these, in the authors’ opinion, is the knowledge of the processes of barrier-dismantling and barrier generation. Furthermore, in close correlation with this, a deeper understanding of the perspectives of disabilities must also be reached.

The appearance of travel, accessibility, disability and network organisational view were all examined also through the hermeneutical analysis of the audio-visual sources featured in the list of references. The finding achieved, which may come as a total surprise for many, is the fact that the authors and interpreters dealing with Buddhism—including, of course, contemporary philosophers—do not use these words in their explicit form at all. Nevertheless, their thoughts carry, irrespective of their date of birth, an accessibility-centred attitude in themselves and they pay attention to the “enumeration” of our disabilities; these, however, are derived from the non-recognition of the symbiotic network that creates, develops and maintains existence. Special attention should be paid to the collection of the teachings of the Zen master Eihei Dogen: Shobogenzo Zuimunki [

50]. In this collection the Zen philosopher, who was born in 1200 and learnt from a Chinese master the practice of Sōtō Zen, brought to his homeland, Japan, knowledge from the “Middle Empire”. He has still been considered to be the founding father of Zen in Japan. In a specific way Dogen recognised, through the already-mentioned model of dependant origination, both the possibilities and hindrances lying in one of the basic structures of our existence: networking. In this approach—although in an implicit manner—existential disability as a basic feature of man is reinforced once again [

2].

4. Conclusions

The thoughts put on paper, the philosophical analyses and the conclusions are meant to be a thought-provoking work. The authors’ main goal was to embed networking and its research into a life philosophy model whose roots go back thousands of years in time.

The significance of the discipline of science is indisputable; it is enough to take into consideration the magnitude of the economic indices of tourism [

51]. It was also already recognised, on the other hand, both by researchers and decision-makers decades ago that tourism was not only an economic phenomenon but also a socio-cultural one, with considerable impact on the quality of life of the members of a society. The 1960s and 1970s were already the decades of classic mass tourism, and the detrimental social and ecological phenomena caused by tourism became clearly visible, to which tourism experts reacted quickly, e.g., Krippendorf in his book published in 1975, entitled “Die Landschaftsfresser (“The Landscape Eaters”). Jungks named the practice of traditional mass tourism “hard tourism”, and also outlined an opposing vision, which led to the birth of the concept of mild tourism in which economic, ecological, sociological and political aspects were also taken into consideration. The appearance of mild tourism was an interesting and important counter-reaction at a time when hedonism and indulgence were the dominant trend in tourism [

52].

The so-called Manila Declaration was approved more than four decades ago, at the World Tourism Conference organised by UNWTO (United Nations World Tourism Organization). This document paid attention to “the responsibility of States for the development and enhancement of tourism in present-day societies as more than a purely economic activity of nations and people. … The economic returns of tourism, however real and significant they may be, do not and cannot constitute the only criterion for the decision by States to encourage this activity … tourism constitutes a positive element for social development in all the countries where it is practised irrespective of their level of development” [

53]. The Declaration emphasised, furthermore, that, “In the practice of tourism, spiritual elements must take precedence over technical and material elements. The spiritual elements are essentially as follows: (a) the total fulfilment of the human being; (b) a constantly increasing contribution to education; (c) equality of destiny of nations; (d) the liberation of man in a spirit of respect for his identity and dignity; (e) the affirmation of the originality of cultures and respect for the moral heritage of peoples.” [

53].

At the end of the same decade, in April 1989, the Hague declaration was published at the conference of UNWTO and the Interparliamentary Union (IPU) in the Netherlands, The Hague. This document invites decision-makers to meet further criteria for the sustainable development of tourism, emphasising, among other things, national tourism policy, complex planning, making tourism acts and tourism regulations, the teaching of tourism but also the easement of travels [

54,

55].

Although mass tourism has not disappeared in the past decades (and is not expected to disappear in the coming decades, either), the emphasis has increasingly shifted from quantity to quality; experience-packed, beatific travel is coming to the fore [

39,

47,

56], in which travellers living with disabilities wish to participate in growing numbers [

57,

58,

59,

60].

The authors are convinced that it is a mistake by researchers and lecturers to only consider travellers to be nothing but statistical data who generate revenues or expenditures. The authors are pleased that, also due to the complexity of the processes going on in the world, and to the resilience factor of the possible reactions to these, the teaching of philosophy in higher education seems to be on the rise again after a descending track, as the major decision-makers of politics, economics and education are coming to realise the organising and accessibility-creating nature of philosophy, and so increasing emphasis is put on both the training and application of philosophical dimensions. The multi-structural and life philosophy

contemplation of networks, recommended by the authors, is meant to prove that what is a junction from one aspect is a “simple” information transmission medium from another one [

61].

If we try to analyse only from a fixed conscious situation the multi-dimensional networks of being and existence (void of any constant centres, though), we may easily interpret it as a labyrinth of barriers, which of course must evidently be made barrier-free, i.e., accessible. However, if we are able to immerse into the networks of existence, we will realise that we could and can never exist outside these, as we are elements, creators and spectators of the circle of life at the same time. In other words, we will be able again to apply our concept and capability of accessibility, to be able to get to know the nature of barriers, during which we will realise that not all barriers can and should be removed, as many of them are only barriers to our existence at first glance.

To sum it up, the paper is not meant to draw even general conclusions about the interconnections of network science, philosophy and the discipline of travelling. One of the aims of the paper is simply to raise the interest of the readers, following the path along the concept-origination defined by Heidegger [

62] and the topic of travelling. Another goal is to allow travel science experts and academics in different disciplines to enlarge their knowledge and analytical skills, and to have professional discourses and philosophical discussions organised around the cornerstones indicated in the paper: Buddhist emptiness philosophy, travel science and networking.