Abstract

The dynamics of household and regional economy of Banni grasslands in India were studied based on primary data collected from 280 households across 13 villages. Each household had one primary occupation and, on average, two secondary occupations. Pastoralism and charcoal production employed 58 and 28% of households as primary occupations, respectively, whereas leather work, services and tourism employed 4% of households each. Further, pastoralism and charcoal production employed 60 and 48% of households, respectively, as secondary occupations. Highest and lowest average annual net returns were realized from the sale of milk and milk products (₹ 414,070/HH) and honey and gum collection (₹ 2827/HH), respectively. The Banni grassland is still a traditional society predominantly based on the primary sector as it employed 88% of the households and contributed 91% to the economy. Pastoralism alone contributed 82% to the economy of the Banni region followed by charcoal production (8%) and tourism (5%), whereas all other occupations contributed <1–2% each. Contribution from secondary and tertiary sectors was very low. Pastoralism has evolved in the region, but it continues to be the dominant livelihood option. Therefore, arresting and addressing the land degradation process in Banni grasslands is of paramount importance to sustain the livelihoods and the ecology.

1. Introduction

The Banni grassland in Bhuj taluka in the Kachchh district of Gujarat is spread over about 2600 km2 area and is the largest natural tropical grassland in the Indian subcontinent. It is surrounded by Wagad and Beta Islands in the east, Pachham Island in the north, Great Rann in the northwest and Little Rann and Kachchh mainland in the south. The Kachchh district is bounded in the north and northwest by Sindh province of Pakistan. Consisting of two ecosystems in juxtaposition, viz., wetlands and grasslands, Bannis fall under the Dichanthium-Cenchrus-Lasiurus type of grass cover [1]. The Banni region experiences an arid climate with an average annual rainfall of 317 mm (with a coefficient of variation of 65%) received by the southwest monsoon between June–September [2,3]. Recurrent droughts are a common phenomenon in Banni and other parts of the Kachchh region. During the period between 1932 and 2013 (82 years), the Kachchh district experienced a total of 48 drought years in which 26 years faced severe to very severe droughts [4,5]. Despite harsh abiotic environmental features, Banni is endowed with relatively rich biodiversity [6]. Despite the inherent salinity of its alluvial sandy lands, it is Asia’s finest grassland [7,8].

There are 48 hamlets/villages in the Banni area organized into 19 Panchayats (local democratic self-governance unit for a cluster of 2–3 neighbouring villages) with a population of 21,338 people in 2011–2012 [9]. The nomadic (presently semi-nomadic and sedentary) pastoralist communities, generally known as Maldharis, comprise 22 ethnic communities. Maldharis are landless, and migratory pastoralism is the main source of livelihood. They are dependent on gauchars (village commons/ rangelands) for their livestock rearing. Banni buffaloes, Kankrej cattle, Pathanwadi and Duma/Marwari sheep, Kachchhi goat, Kachchhi and Tari camel and Sindhi horse are the domesticated animals [10,11]. Livestock is the mainstay of the inhabitants of Banni, and the area is a well-known cattle-breeding tract of Gujarat [8]. Maldharis are known not only as livestock herders but also for their skills in breeding superior cattle and buffalo breeds [12]. Banni buffalo was recognized as the distinct buffalo breed of the country in 2010 [13].

Livestock rearing is the traditional occupation and the predominant source of income for pastoralists. However, significant changes have occurred in Banni after India’s independence in 1947 such as the declaration of Banni as a Protected Forest in 1955, lack of community grazing rights of Maldharis over Banni, increasing soil salinity, invasiveness of P. juliflora, the shift in livestock composition (from cattle to buffalo), improved road connectivity and development of organized dairy industry [11,14,15].

There are eleven distinct livelihood options and enterprises practised by the pastoralists in Banni grasslands. Among these, Banni buffalo-based pastoralism, Prosopis juliflora-based charcoal production, sheep and goat rearing, leather work, services, tourism and trade were the primary occupations whereas embroidery, honey collection, gum collection and labour were the secondary occupations [11]. The purpose of this study was to investigate whether pastoralism is still the dominant livelihood option to the pastoralists and the Banni economy in the context of significant socio-economic, policy and ecological changes in the last 7–8 decades. The objectives of this research paper were: (i) to estimate the contribution of different enterprises to the household incomes of pastoralists; and (ii) to estimate the contribution of different enterprises to the Banni region’s economy.

This article is structured into six parts. The Introduction part provides brief information on Banni grasslands, livelihood options for pastoralists, the purpose and objectives of the study. The study area, research design, sampling procedure and size and statistical/economical tools used for the study are provided in the Materials and Methods section. The Results section focuses on different livelihood options practiced by pastoralists and their contribution to the household and the Banni region’s economy. The Discussion section highlights the challenges to the livelihood security and the ecology of Banni grasslands especially due to desertification by expansion of P. juliflora. The Conclusion section summarizes the findings with policy implications and future research and development gaps followed by the references cited in the article.

2. Materials and Methods

Research design: an ex post facto and survey research design were adopted for the study.

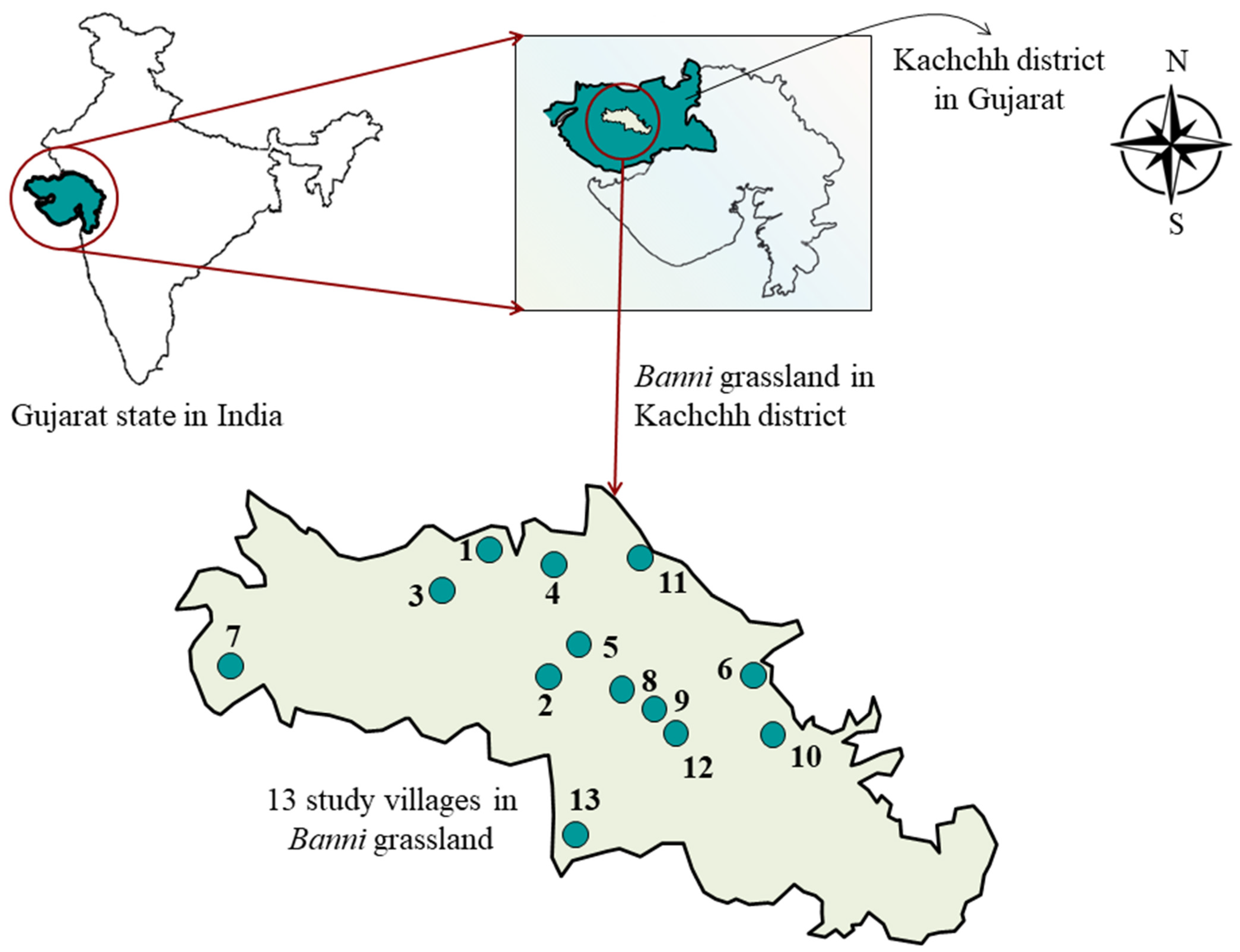

Locale of the study, sample and sampling procedure: Banni grasslands (23°19′ to 23°52′ N latitude and 68°56′ to 70°32′ E longitude) located in the Bhuj taluka (subdivision/administrative block) in the Kachchh district of Gujarat State in India were purposively selected as the study area. There are 48 villages in the administrative jurisdiction of Banni grasslands. Thirteen villages (Dhordo, Hodko, Patgar, Uddo, Varli, Sadai, Burkhal, Mehar Aliwand, Madhavnagar, Udai, Sargu Nava, Bhirandiyara and Jura) were selected for the study using stratified sampling technique to represent different parts of Banni (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Representative map of Banni grasslands in Kachchh district of Gujarat in India. The circles in the Banni grasslands represent following villages: (1) Dhordo; (2) Hodko; (3) Patgar; (4) Uddo; (5) Varli; (6) Sadai; (7) Burkhal; (8) Mehar Aliwand; (9) Madhavnagar; (10) Udai; (11) Sargu Nava; (12) Bhirandiyara; and (13) Jura. Note: Map is not to scale and prepared only for representational purpose.

Data collection tools and analysis: A structured interview schedule was developed specifically for the study. The primary data were collected between July 2014 and June 2019 by personally interviewing 280 households (4.69% of all households in Banni) selected randomly from these 13 villages (27% of the villages in Banni). The respondent households were classified into various categories based on the combination of primary and secondary occupations contributing to their household annual income. Annual incomes were calculated for the agricultural year 2016–2017 based on the prices prevailing in the Banni region in April 2017 [11]. The guidelines on methods for estimating livestock production and productivity developed FAO were followed [16]. The total rainfall received in Banni grasslands in 2016 (January–December) was 224 mm, which was 71% of the average annual rainfall (317mm). Hence, 2016 was a mild and moderate drought year (50-75% of average rainfall). There were 4261 families in Banni grasslands with a human population of 21,338 as per the 2011–2012 census (average family size was five). The human population in 2016–2017 was projected to be 29,873 (by taking a decadal growth rate of 80% as prevalent in the region as per census reports) with 5975 families (taking an average family size of five as prevalent in 2011–2012). The contribution of different livelihood options/enterprises to the annual income of pastoralist households and the economy of the Banni region was analysed using descriptive statistics.

The primary data collected from pastoralist households were corroborated through extensive field visits to Banni grasslands and pastoralists’ livestock yards at their home and during migration. Charcoal production units were visited. Embroidery and leather work units were visited at the selected respondents’ houses and exhibition stalls during Rann Utsav (A tourism event organized by the Government of Gujarat every year from November to March in the white desert at Rann of Kachchh). Focused Group Discussions (FGDs) were held with key pastoralists in each village and other stakeholders such as representatives of the Banni region (Banni Breeders Association) and researchers and organizations working on Banni grasslands, which helped in supplementing and validating the primary data collected from individual households. Household sample survey is the most widely used method to generate the primary data in social science research involving human participants, such as in studies on transhumance and the impact of climate change on agriculture. Such data are supplemented by qualitative and quantitative data generated from many other techniques, such as Participatory Rural Appraisal, Focus Group Discussions, discussion with key informants and participant observation among other techniques [17,18]. Such techniques were also used to supplement findings of research on the impact of air pollution from brick kilns on public health [19].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Relative Contribution of Different Livelihood Options to the Household Economy

There are eleven distinct livelihood opportunities practised by pastoralist households in Banni grasslands [11,15]. The sale of milk and milk products and the sale of buffaloes/cattle (cows/bullocks) are part of pastoralism. However, these are shown separately in this article to highlight the variation in the number of households dependent on these livelihoods as primary and secondary enterprises. Further, honey collection and gum collection are different enterprises. However, these enterprises are practised by the same set of households during the same time in the year and the incomes are so low and insignificant [11]. Hence these two enterprises were merged for this article (Table 1).

Table 1.

Livelihood options in Banni grasslands and their contribution to household income (n = 280).

It was found that each pastoralist household had, on average, three sources of livelihood and income. The livelihood option which contributed the highest annual income (and % share) among all livelihood options practised by that household is considered the primary occupation. The rest of the livelihood options are considered secondary occupations for that household. Therefore, each household had one primary occupation and, on average, two secondary occupations. The number of livelihood options practised by the respondent households varied from 2 to 5. The total number of secondary occupations (Table 1) is 573 because the majority of households had more than one secondary occupation (for example charcoal production and goat rearing or charcoal production and embroidery). Refer to Manjunatha et al. [11] for the detailed combinations of different enterprises practised by the households. However, this article is focused on the contribution of different enterprises to the annual incomes of households and the Banni region’s economy.

Pastoralism was the predominant source of livelihood in the Banni region as it supported 56% of households as a primary occupation. Migratory pastoralism has been gradually replaced by semi-migratory/sedentary pastoralism and the organized dairy industry. The Banni buffalo-based dairy industry is the predominant occupation and pastoralists are engaged in the sale of milk and milk products. Many pastoralists also sold a few Banni buffaloes or Kankrej bullocks every year. As evident from Table 1, it was a primary occupation for only 2% of families; however, it was a secondary occupation for 39% of households. Charcoal production employed 75% of families; 28% as a primary and 48% as a secondary occupation. However, the mean net annual income from charcoal production was significantly less than the sale of milk and milk products. Sheep and goat rearing were practised by 22% of households and it was the primary occupation for only 2% of households. Mean net income was less than the charcoal production indicating that the poorest households reared few goats for generating additional income. Very few households reared sheep, but the herd size was >100 per household. Honey and gum collection were practised by the Koli community as an additional income-generating activity during a few months of the year and the incomes generated were too low [11]. Embroidery on clothes was practised by the women in each Muslim and Hindu Meghwal household, but it was not an economic activity for all households [11]. Household and hired labour were an integral and indispensable part of all livelihood options practised in the Banni grasslands. However, labour in the present study meant labour engaged in Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA) and agricultural and non-agricultural labour during migration outside the Banni grasslands.

Further analysis revealed that the sale of milk and milk products generated the highest net annual incomes (₹ 414,070/household). Those who sold livestock earned additional net returns of ₹ 104,050/household. The sale of milk and milk products contributed to annual net income ranging from ₹ 10,800/- to 1,783,400/- among different households. It contributed 15.38 to 95.29% of the total income of the households. Charcoal production generated net annual incomes of ₹ 45,821/household (around 1/9th of the incomes generated from the sale of milk and milk products). The annual net income generated by leather work was ₹ 106,913/household and was higher than charcoal production. Only the Meghwal community was engaged in leatherwork since it was their traditional occupation. The average net annual incomes generated from honey and gum collection were the lowest (₹ 2827/household) indicating the poor socio-economic status and poverty among the Koli community that is engaged in this livelihood.

The livestock composition as per the 1983 census was 45% buffalo (22,174), 20% cattle (9625), 33% sheep and goats (16,502) and the remainder are camels, horses and asses. Kankrej and Thani are famous breeds of cattle. On average, each well-to-do Maldhari family maintained 35–50 cattle and earns ₹ 6000 to 10,000 ($USI90-320) per month [21]. The cultural-economic shift from a bull to milk economy brought about a shift in the Banni cattle/buffalo ratio, with the proportion of buffalo increasing from 15% to 45% to 64% in 1960, 1982 and 1992, respectively [4]. As per the 2011–2012 census, the buffaloes constituted 72% of the livestock population in Banni grasslands followed by cattle at 16%, whereas the goat and sheep together contributed 13% [10]. The Kankrej cattle are dual-purpose (milch and draft) breeds. Mechanization of agriculture has led to a reduction in the use of Kankrej bullocks for draught purposes. Hence, domestication of the Kankrej breed only for milk production is less economical when compared to Banni buffalo. The milk productivity of Banni buffaloes is higher and hence they are more preferred over Kankrej cows [10].

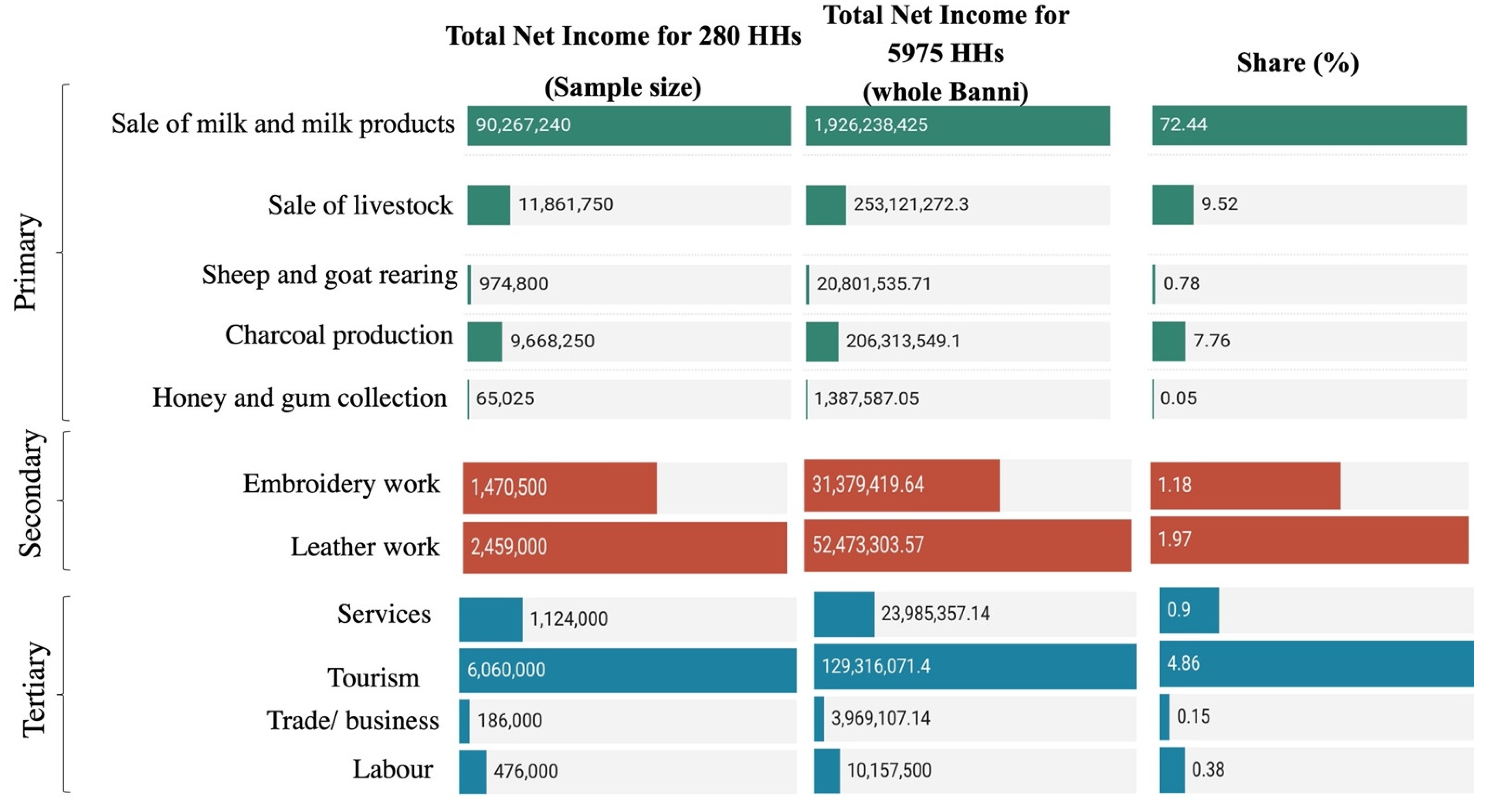

3.2. Relative Contribution of Different Livelihood Options to the Banni Region’s Economy

The structure and composition of the Banni region’s economy are provided in Figure 2. It indicated that Banni grassland is still a traditional society predominantly based on the primary sector both in terms of employment and incomes [15]. Pastoralism (sale of dairy products and livestock) is still the predominant occupation in Banni grasslands as it contributed 82% to the region’s economy (Figure 3). The contribution from the rearing of small ruminants (sheep and goat), honey and gum collection were too low and insignificant. The secondary sector contributed around three per cent to Banni’s economy. The tertiary sector contributed 6.3% mainly through tourism. The contribution from services was <1% indicating the absence of alternate livelihood options for the youth in the region. Contributions from trade and labour were very low and insignificant.

Figure 2.

Structure and composition of the Banni region’s economy.

Figure 3.

Contribution of different enterprises to the Banni region’s economy in 2016–2017.

Charcoal production, though employed by 75% of households (Table 1), contributed only 7.76% to the regional economy indicating that it was practised by those households who did not own buffaloes or who owned few buffaloes for meeting their domestic consumption needs. It was a secondary occupation for many households during drought years and off-season. Charcoal production was found to be less sustainable (ecological, economic and socio-cultural indicators) than sheep and goat rearing [15]. Embroidery, though practised by every household in the region, was an economic activity in only a few villages near the Rann of Kachchh that benefitted from the tourism industry. Tourism initiatives by the Government of Gujarat at Rann of Kachchh since 2006 have provided new and alternative employment opportunities. Tourism has the scope to further generate employment opportunities and incomes.

4. Discussion

The extent of employment and incomes generated from primary sector livelihoods were greatly affected by the rainfall. In the normal rainfall year, pastoralism provided employment throughout the year. The sale of milk and milk products was high from July/August to December/January when the green grass is available in plenty for free in the grasslands. The milk production would reduce from January to June because of a reduction in green grass cover in the grasslands. However, during the low rainfall/drought years, the green grass cover would exhaust early in the grasslands leading to an increase in costs of livestock rearing (towards the purchase of supplementary feed and fodder resources especially for lactating animals) and an overall reduction in milk production. Low rainfall/drought also leads to migration of pastoralists (especially those with large herd size) along with their livestock with the consequences of very low milk productivity, distress sale of milk and animals increased drudgery and other social problems. The same was true for sheep and goat rearing. The sheep rearing pastoralists with large herd sizes are more prone to migration. Charcoal production was undertaken throughout the year except during the rainy season (generally for 8–9 months in the normal rainfall years). During drought years, charcoal production would depend on the extent of P. juliflora available. The secondary and tertiary sector livelihoods were less affected by variation in rainfall. However, the population dependent on such livelihoods was very low. Leather work was undertaken for about eight months in the year (except during the rainy season). Gum and honey collection from P. juliflora and other forestry trees was undertaken for a few months in summer (March to May). Tourism benefitted a few villages around Rann of Kachchh from November to March.

Land degradation/desertification is another important aspect severely affecting the livelihoods in Banni grasslands. Banni grasslands provided an ideal region for animal husbandry but successive droughts and excessive animal pressure have virtually left P. juliflora and Suaeda fruticosa as the only perennials [22]. Prosopis juliflora’s introduction to Banni grasslands in the 1960s triggered a sequence of ecological, social, economic and policy changes in Banni and beyond [23]. The rapid invasion of juliflora has resulted in a drastic reduction of grazing areas, both in terms of extent and species composition. The successive droughts, increasing salinity and excessive grazing pressure provided a highly suitable environment for the growth and spread of P. juliflora [24]. The ecological succession changed the structure of the vegetation complex and entire area was dominated by P. juliflora in terms of distribution, abundance, basal cover and canopy cover [25] and it has spread to 1500 km2 by 2010s in Banni [3,26]. The land degradation/desertification process in Banni is not attributed to climate variation and/or land users’ mismanagement but the invasion of alien species (P. juliflora). The concurrent processes of soil salinization and P. juliflora invasion triggered desertification and land degradation. Overgrazing, leading to loss of vegetation cover, soil erosion, salinization and further expansion of P. juliflora at the expense of grass-covered lands represents a classic land degradation/desertification scenario [23]. The density of P. juliflora ranges from 96 to 1450 plants per hectare across Banni villages [27,28]. Banni grasslands continue to face degradation. The main drivers of change include increasing soil salinity, invasion by Prosopis juliflora, grazing pressures, water scarcity, climate change and desertification [5,14]. A study using Remote sensing and GIS techniques assessed that barren land has significantly increased from 43% in 1989 to 68% in 2009 of the total area in Banni grassland with an overall increase of 179,162 ha in two decades [29].

With milk production peaking at 50,000–80,000 litres/day in 2015 and the revival of the bull trade, Banni’s annual per capita income (based on the 2001 human population of 16,783) from milk and animal sales combined rose to $518–$791. Nevertheless, Banni grassland’s cattle and buffalo-based livelihood could not remain sustainable at the turn of the 20th century. Its 7-kg/animal/day grass consumption [30] of Banni’s 57,898 adult cattle units (ACU) in 2007 (an annual requirement of 192,994 tons) created a yearly deficit of 18,815 tons [31]. Local people had observed a change in the habitat from grassland to woodland (dominated by Prosopis juliflora) during their lifetime and considered it primarily a result of frequent intensive drought, dams constructed on flooding rivers in Banni and declining rainfall [8].

Studies by various organizations have suggested measures to improve the overall productivity and sustainability of Banni [32,33,34,35,36,37]. However, most of these recommendations were either never executed or were executed without an ecological approach. Therefore, rejuvenation and restoration of Banni into a sustainable productive ecosystem requires a holistic ecological approach [5] and timely spatial assessment and monitoring of P. juliflora invasion in such extreme environments [38]. Past grassland development or restoration efforts by the government in the 1990s collapsed shortly after implementation due to the lack of ownership as the communities were never involved during the planning stages [8].

Many pastoralists, mostly young, have left their villages and even the district, seeing no hope for their future in this occupancy as a result of the deteriorating Banni grasslands [8]. Shrinking grassland and its productivity has a cumulative impact on the livestock-based sustenance of Maldharis in Banni [5]. Pastoralism (though changed from nomadic to semi-nomadic and sedentary) is still the principal livelihood option in the Banni grasslands. Maldharis have cultural and ecological linkages with pastoralism besides economic significance. Therefore, scientific management of rapidly expanding P. juliflora and rejuvenation of native grasses and shrubs is critical for arresting land degradation/desertification and thereby enhancing the sustainability of livelihoods.

Future research areas: (i) The household annual incomes in this study were calculated based on returns generated from economic activities. For instance, women in the majority of the households in the Banni grasslands were involved in embroidery, only for domestic use and not for commercial sale. Such unpaid labour/services were not taken into account for calculation of returns. Therefore, incomes calculated from other methods (expenditure method) may vary slightly. (ii) The annual incomes were calculated for the agricultural year 2016–2017, which was a mild and moderate drought year. However, incomes vary significantly from year to year depending on the amount of rainfall. Future research studies may focus on variation in household incomes from normal rainfall year to moderate drought (50-75% of average rainfall) and severe drought (<50% of average rainfall) years, especially the contribution of pastoralism vis-à-vis other occupations. (iii) What is the carrying capacity of the Banni grasslands in terms of the number of human and livestock population it can sustain during normal rainfall years and drought years? This is a key factor that decides the profitability and sustainability of pastoralism, and consequently, whether the younger generation will stay back in pastoralism or migrate to cities for other employment opportunities. (iv) The data for this study were collected only from male pastoralists because of the socio-cultural restrictions in reaching women in the region. Therefore, women pastoralists’ voice/views may not be represented adequately. Future studies may make efforts in reaching women pastoralists by employing female researchers or trained female data enumerators from the Banni region.

5. Conclusions

Migratory pastoralism was the traditional occupation in the Banni grasslands for five centuries. It is being replaced gradually by semi-migratory and sedentary pastoralism/ livestock rearing in the last few decades owing to the combination of policy factors, land degradation and pastoralists’ adaptation strategies. However, pastoralism continues to be the dominant economic driver in the region both at the household and economy levels. Pastoralism employed 58% of households as a primary occupation and accounted for 15 to 95% of their net income. The sale of milk and milk products generated the highest average annual net returns (₹ 414,070/HH) over all other occupations. Further, it contributed 82% to the economy of the Banni region. Charcoal production, dependent on the cutting of ever-expanding Prosopis juliflora, is the distant and second most important economic driver in the region. It employed 28% and 48% of households as primary and secondary occupations, respectively. It contributed ₹ 13,500/- to 360,000/- to the households’ annual income. The Banni grassland is still predominantly based on the primary sector, as it employed 88% of the households and contributed 91% to the economy. Contribution from secondary and tertiary sectors was very low.

It is interesting to note that pastoralism is still the largest contributor of employment and incomes in Banni grasslands though it has undergone significant changes since India’s independence. How to keep pastoralism remunerative and attractive to the young generation while sustaining the production levels remains the key concern at present. Enhancing the carrying capacity of the Banni grasslands through adoption of scientific technologies and linking pastoralists in remote villages with dairy supply and value chain will reduce migration of people out of the Banni grasslands. It is crucial to conserve the pastoralist traditions through multi-pronged research, policy and development strategies in participatory mode with the pastoralists. Arresting and addressing desertification is crucial for sustaining the livelihoods in the Banni region. Research on arresting the expansion of P. juliflora and its utilization for animal feed and other uses are to be explored. Promotion of sheep and goat rearing among poor pastoralists as an alternative to charcoal production is more sustainable. Community participation of Maldharis in the conservation of Banni grasslands calls for recognizing and granting their community rights over Banni. Pastoralism should not be seen just as an economic activity but a way of life in which pastoralists, livestock, land and culture are inseparable parts of a dynamic system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.L.M., D.H. and P.T.; methodology, B.L.M., D.H. and P.T.; software, B.L.M. and A.N.; validation, B.L.M., D.H. and P.T.; formal analysis, B.L.M., A.N. and D.H.; investigation, B.L.M.; resources, B.L.M. and P.T.; data curation, B.L.M., D.H. and A.N.; writing—original draft preparation, B.L.M. and D.H.; writing—review and editing, B.L.M., D.H., A.N. and P.T.; visualization, B.L.M. and A.N.; supervision, B.L.M. and P.T.; project administration, B.L.M. and P.T.; funding acquisition, B.L.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Central Arid Zone Research Institute of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare, Government of India.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the pastoralist households (the respondents of the study) in the Banni grasslands for sharing their information, knowledge and wisdom for this research and other stakeholders (representatives of the Banni region, researchers and organizations working on the Banni grasslands) who shared and validated the information. We also sincerely thank the Hon’ble Director, ICAR-Central Arid Zone Research Institute (CAZRI), Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India for his guidance and constant support at all stages of this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dabadghao, P.M.; Shankarnarayanan, K.A. Grass Cover of India; Indian Council of Agricultural Research: New Delhi, India, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Banni. Biodiversity. Available online: http://banni.in/biodiversity/grasslands/ (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Ramble. About Banni. Website of Research and Monitoring in the Banni Landscape (RAMBLE). Available online: https://bannigrassland.org/banni/ (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- Kumar, V.V.; Nikunj, G.; Patel, P. Grasslands of Kachchh. In State of Environment in Kachchh; Kathju, K., Vijay Kumar, V., Thivakaran, G.A., Patel, P., Veluswamy, D., Eds.; Gujarat Ecological Education and Research (GEER) Foundation, Gandhinagar and Gujarat Institute of Desert Ecology (GUIDE): Bhuj, India, 2011; pp. 113–132. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.V.; Roy, A.K.M.; Patel, R. Ecology and Management of ‘Banni’ Grasslands of Kachchh, Gujarat. In Ecology and Management of Grassland Habitats in India; ENVIS Bulletin: Wildlife & Protected Areas; Rawat, G.S., Adhikari, B.S., Eds.; Wildlife Institute of India: Dehradun, India, 2015; Volume 17, p. 240. [Google Scholar]

- GUIDE. An Integrated Grassland Development in Banni, Kachchh District, Gujarat State; Progress Report for the Period between April 2010 and March 2011; Gujarat Institute of Desert Ecology: Bhuj-Kachchh, India, 2011; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- GUIDE. Status of Banni Grassland and Exigency of Restoration Efforts; Study Report; Gujarat Institute of Desert Ecology: Bhuj, India, 1998; p. 66. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, P.N.; Kumar, V.; Koladiya, M.; Patel, Y.S.; Karthik, T. Local perceptions of grassland change and priorities for conservation of natural resources of Banni, Gujarat, India. Front. Biol. China 2009, 4, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directorate of Animal Husbandry. Livestock Data Pertaining to 48 Villages in Banni Grasslands Collected by Researchers from Animal Husbandry Office, Bhuj (Agriculture, Farmers Welfare and Cooperation Department, Government of Gujarat) Specifically for THIS Study; Directorate of Animal Husbandry: Bhuj, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Manjunatha, B.L.; Sureshkumar, M.; Tewari, P.; Dayal, D.; Yadav, O.P. Livestock population dynamics in Banni grasslands of Gujarat. Ind. J. Animal Sci. 2019, 89, 319–323. [Google Scholar]

- Manjunatha, B.L.; Shamsudheen, M.; Sureshkumar, M.; Tewari, P.; Dayal, D.; Yadav, O.P. Occupational structure and determinants of household income of pastoralists in Banni grasslands in Gujarat. Ind. J. Animal Sci. 2019, 89, 453–458. [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan, V.; Bharwada, C. Pastoral Livelihoods of Banni: Case of Bullock Trade. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Banni Grassland, Kachchh, India, 4–5 March 2011; Organized by Gujarat Institute of Desert Ecology: Bhuj, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- NBAGR. Banni Buffalo Accession Number: INDIA_BUFFALO_0400_BANNI_01011. Registered Breeds of Buffalo. National Bureau of Animal Genetic Resources. Available online: http://www.nbagr.res.in/regbuf.html (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- Dayal, D.; Dev, R.; Sureshkumar, M.; Manjunatha, B.L. Managing Banni Grasslands: Issues and Opportunities. Indian Farming 2018, 68, 112–114. [Google Scholar]

- Manjunatha, B.L.; Shamsudheen, M.; Sureshkumar, M.; Tewari, P. Ecological, economic and socio-cultural sustainability of different livelihood options and enterprises practised by pastoralists in Banni grasslands of Gujarat. Ind. J. Animal Sci. 2021, 91, 305–312. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Guidelines on Methods for Estimating Livestock Production and Productivity; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2018; p. 173. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, W.; Rahim, I.; Nafees, M.; Rehman, S.A.U.; Khurshid, M.; Shi, J. Making goat herders as scape goats for high-altitude pasture degradation: A case study of Haripur-Naran pastoral system in northern Pakistan. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2019, 29, 953–963. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, W.; Nihei, T.; Nafees, M.; Zaman, R.; Ali, M. Understanding climate change vulnerability, adaptation, and risk perceptions at household level in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strateg. Manag. 2018, 10, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.S.; Ullah, S.; Javed, M.F.; Ullah, R.; Akbar, T.A.; Ullah, W.; Baig, S.A.; Aziz, M.; Mohamed, A.; Sajjad, R.U. Assessment and Impacts of Air Pollution from Brick Kilns on Public Health in Northern Pakistan. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exchange Rates. Available online: https://www.exchangerates.org.uk/USD-INR-07_04_2017-exchange-rate-history.html (accessed on 27 August 2022).

- Bharara, L.P. Preliminary Report on Socio-Economic Survey of Banni Area, Kutch District (Gujarat); Central Arid Zone Research Institute: Jodhpur, India, 1987; p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, A. Banni Grassland and Halophytes: A Case Study from India. In Halophytes as a Resource for Livestock and for Rehabilitation of Degraded Lands; Squires, V.R., Ayoub, A.T., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1994; pp. 217–222. [Google Scholar]

- Uriel, N.S.; Vijay Kumar, V. Land Degradation and Restoration Driven by Invasive Alien—Prosopis Juliflora and the Banni Grassland Socio-Ecosystem (Gujarat, India). Glob. J. Sci. Front. Res. H Environ. Earth Sci. 2021, 21, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Tewari, J.C.; Harris, P.J.C.; Harsh, L.N.; Cadoret, K.; Pasiecznik, N.M. Managing Prosopis Juliflora (Vilayati Babool)—A Technical Manual; CAZRI, Jodhpur and HDRA: Coventry, UK, 2000; p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- Tewari, J.C.; Ratha Krishnan, P.; Harsha, S.L.; Bohra, H.C. Prosopis Juliflora: Past, Present and Future; Tewari, J.C., Ratha Krishnan, P., Harsha, S.L., Bohra, H.C., Eds.; Desert Environmental Conservation Association (DECO), Jodhpur and Central Arid Zone Research Institute (CAZRI): Jodhpur, India, 2011; 115p. [Google Scholar]

- SAC. Prosopis Juliflora Mapping in Saurashtra and Kachchh, Gujarat Using Remotely Sensed Data and GIS Technique; Space Application Centre, ISRO: Ahmedabad, India, 2002; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- GUIDE (Gujarat Institute of Desert Ecology) and GSFD (Gujarat State Forest Department). An Integrated Grassland Development in Banni, Kachchh District, Gujarat State; Progress Report; Gujarat Institute of Desert Ecology (GUIDE): Bhuj, India, 2010; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, Y.; Dabgar, Y.B.; Joshi, P.N. Distribution and Diversity of Grass Species in Banni Grassland, Kachchh District, Gujarat, India. Int. J. Sci. Res. Rev. 2012, 1, 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, A.; Sinha, M.; Chaudhary, R. Evaluation of land cover changes in Banni grassland using GIS and RS Technology-A Case Study. Bull. Environ. Sci. Res. 2014, 3, 18–27. Available online: http://besr.org.in/index.php/besr/article/view/56 (accessed on 27 August 2022).

- Bhimaya, C.P.; Ahuja, L.D. Criteria for determining condition class of rangelands in western Rajasthan. Ann. Arid. Zone 1969, 8, 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- GUIDE. Grassland Action Plan for Kachchh District, Gujarat State. Part of Kachchh Ecology Planning Project Phase-II; Final Study Report Submitted to UNDP: Gandhinagar, India, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Government of India. Report on the Reclamation and Development of the Great Rann of Kachchh; A Report Submitted to the Ministry of Agriculture; Government of India: New Delhi, India, 1966.

- Ground Water Institute, Pune. Report on Preliminary Survey of Ground Water Resources for Providing Drinking and/or Irrigation Water to Banni Area of Bhuj Taluka, Kutch district; Ground Water Institute: Pune, India, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Indian Council of Agriculture Research. Report of the ICAR Committee on Research and Development Programmes in the Kachchh District (Gujarat); ICAR: New Delhi, India, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Proceedings of the Conference on Common Property Resource Management, WA, USA, 21–26 April 1986; National Academy Press: Washington, WA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Soil Survey Division. Report on the Reconnaissance Soil Survey Carried out in Banni Area in Kachchh District of Gujarat State; Soil Survey Division: Vadodara, India, 1986.

- WRD; CDO. Report of the Sub-Committee for Studying the Problems and Suggesting the Remedial Measures for the Salinity Ingress in the Banni Area of Kachchh District; Government of Gujarat, Water Resources Department and Central Designs Organization: Gandhinagar, India, 1989.

- Dakhil, M.A.; El-Keblawy, A.; El-Sheikh, M.A.; Halmy, M.W.A.; Ksiksi, T.; Hassan, W.A. Global Invasion Risk Assessment of Prosopis juliflora at Biome Level: Does Soil Matter? Biology 2021, 10, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).