Territorial Challenges for Cultural and Creative Industries’ Contribution to Sustainable Innovation: Evidence from the Interreg Ita-Slo Project DIVA

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. CCIs for Sustainable Development

2.2. Methodological Issues Concerning CCIs Mapping

- Difficulty to define and delimit the boundaries of the “cultural and creative sector”, which is given by the complexity, fluidity and heterogeneity of cultural production and consumption processes.

- Lacking suitable and comparable data to build up a comprehensive European map [18].

- Unsettled debate about CCIs identification and classification methodologies, especially when interpreting their activities and evaluating their cultural and creative content.

- Imprecise classification by NACE (Nomenclature of Economic Activities) code classifications in local Chamber of Commerce registers.

- referred to an existing CCIs mapping methodology drawing from considering some manufacturing sectors as cultural and creative activities and the base for the mapping fostering CCIs-traditional SMEs collaboration (refer to Section 4.1 DIVA Approach to CCIs mapping);

- considered the regional and national specificities (Italian and Slovenian) of CCIs data and homogenised them;

- complemented anonymous firms’ data with their geo-localization;

- provided a connection between firms’ data (activity areas, employees’ number, average turnover, years in business) with localization characteristics.

- Urban policies devoted to urban regeneration projects involving CCIs-SMEs

- Cultural policies enhancing slow tourism and urban regeneration

- Economic policies aimed at inclusive growth and sustainable innovation

- Tourism policies aimed at local tourism and valorisation of inner regions and lesser-known contexts.

3. Territorial Framework

CCIs in the Italian Regions of Veneto and Friuli Venezia Giulia, and in the Western Region of Slovenia

4. Methods and Data

4.1. DIVA Approach to CCIs Mapping

4.2. CCIs Mapping

- Area 1: activities of preservation and enhancement of historical and artistic heritage (HERITAGE);

- Area 2: non-reproducible activities of cultural goods and services, such as performing and visual arts (ARTS);

- Area 3: activities related to the production of cultural goods according to a logic of industrial repeatability, as cultural industries (CULTURAL);

- Area 4: creative industries related to the world of services (SERVICES).

4.3. SWOT Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Three Regional CCIs Systems in the Transborder Area

5.2. CCIs Geographies of the Transborder Region

5.3. CCIs Geographies and Needs on Territorial Setups

6. Discussion

- Policy targets: Sustainable Development Goals concerning cities and regional development (particularly SDG 8–11);

- Stakeholders: CCIs classified areas (Art, Culture, Heritage and Services) and their needs;

7. Conclusions

- The research addressed CCIs mapping issues by introducing an appropriate general framework and a consistent mapping technique to systematically recognise place-based CC sectors’ contribution to both the economic and social fabric of a place.

- The extraction and alignment of the two countries’ data put forward in DIVA project is a major contribution to quantitative mapping and will provide a useful tool for public administrations, stakeholders, and policymakers at transnational level. Future research should focus on mapping the fifth area of the creative driven sector to have an even finer-grained mapping.

- Spatial (cluster) and territorial (district) proximity, or being based within the same premises (co-working, S&T parks), is an opportunity for firms as it encourages cooperation, exchange of ideas, innovation, and business possibilities. Therefore, from a policy-making perspective, clustering and spatial proximity between CCIs and SMEs should be fostered through urban policies aiming at introducing mixed-use areas including diverse functions, as well as cultural and economic policies promoting a place-based approach that addresses enterprises’ transnational localisation features.

- Enhancing both accessibility and mobility, as well as hosting firms’ major operational spaces in pilot co-locating premises of urban regeneration projects, could encourage spatial proximity. The building or urban site could be tailor made both for SMEs and CCIs and it could potentially become a landmark on citizens’ mental maps, addressing the CC sectors need to be located in a meaningful, symbolic place.

- Finally, by providing such a detailed socio-economic and territorial portray prior to COVID-19 pandemic, DIVA research results can be a relevant contribution to studies concerning the development of sustainable integrated policies for the post-pandemic reconstruction.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| AREA 1—Activities of Preservation and Enhancement of Historical and Artistic Heritage |

| 91. Artistic and historical heritage |

| 91.01. Libraries and archives 91.02. Museums 91.03. Management of historical sites and monuments 91.04. Activities of botanical gardens, zoos and natural reserves |

| AREA 2—Non-reproducible activities of cultural goods and services, as Performing and visual arts |

| 90. Creative, artistic and entertainment activities |

| 90.01. Artistic representations |

| 90.01.01. Acting activities |

| 90.01.09. Other artistic performances |

| 90.02. Support activities for artistic representations |

| 90.02.01. Structures and equipment rental for events and shows (with operator) |

| 90.02.02. Directing activities |

| 90.02.09. Other artistic representations support activities |

| 90.03. Artistic and literary creations |

| 90.03.02. Works of art conservation and restoration |

| 90.03.09. Other artistic and literary creations |

| 90.04. Management of artistic structures (theatres, musical concerts, etc.) |

| 93. Sport and leisure activities |

| 93.21. Theaters, concert halls and other artistic structures management |

| 93.29. Amusement parks and theme parks |

| 93.29.1. Other recreational and entertainment activities |

| 93.29.2. Discos, dance halls, night clubs and similar activities |

| 93.29.9. Bathing establishments management: maritime, lake and river |

| 93.29.9. Other entertainment and leisure activities |

| 96.09.02. Hairdressers and other beauty treatments |

| AREA 3—Activities related to the production of cultural goods according to a logic of industrial repeatability, as cultural industries |

| 32. Other manufacturing activities |

| 32.4. Video Games and toys production activities |

| 47. Retail sale |

| 47.61. Retail sale of books in specialised stores |

| 47.62.2. Retail sale of stationery articles and office supplies |

| 58. Publishing activities |

| 58.1. Edition of books, periodicals, software and other publishing activities |

| 58.11. Books edition |

| 58.14. Magazines and periodicals edition |

| 58.19. Other publishing activities |

| 58.21. Computer games edition |

| 58.29. Other software edition |

| 59.20.1. Edition of sound recordings |

| 59.20.2. Printed music edition |

| 59.20.3. Sound recording studios |

| 60. Radio and television programming and transmission activities |

| 60.1. Radio broadcasts |

| 60.2. Programming and television broadcasting activities |

| 62. Softwares production |

| 62.01. Production of software not connected to the edition |

| AREA 4—Creative industries related to the world of services |

| 47. Retail sale |

| 47.59.1. Home furniture retail commerce |

| 47.59.2. House tools, cristallerie and tableware retail commerce |

| 47.78.31. Retail sale of art objects (including art galleries) |

| 47.79.1. Second hand books retail sale |

| 47.79.2. Second hand furniture and antiquities objects retail sale |

| 62. Softwares production |

| 62.02. Information technology consultancy |

| 63. Information technology services |

| 63.11. Data processing, hosting and related activities, web portals |

| 63.11.3. Hosting and provision of application services (ASP) |

| 63.12. Web portals |

| 63.91. News agencies activities |

| 63.99. Other information service activities |

| 70. Management consultancies |

| 70.21. Public relations and communication |

| 70.22.09. Other business consultancy and other administrative-management consultancy and business planning |

| 71. Architectural and engineering studios activities |

| 71.11. Architecture firms activities |

| 71.12.2. Integrated engineering design services |

| 72. Scientific research and development |

| 72.2. Research and experimental development in the field of social sciences and humanities |

| 73. Advertising and market research |

| 73.1. ADVERTISING |

| 73.11. Advertising agencies |

| 73.11.01. Advertising campaigns creation |

| 73.11.02. Conducting marketing campaigns and other advertising services |

| 74. other professional, scientific and technical activities |

| 74.10. Specialised design activities |

| 74.10.1. Fashion design and industrial design activities |

| 74.10.21. Activities of graphic designers of web pages |

| 74.10.29. Other activities of graphic designers |

| 74.10.3. Activities of technical designers |

| 74.10.9. Other design activities |

| 74.20. Photographic activities |

| 81. Buildings and landscape services |

| 81.3. Landscape care and maintenance |

| 82. Support services for enterprises and offices |

| 82.3. Organization of conferences and fairs |

| 85. Education |

| 85.52.01. Dance courses |

| 85.52.09. Other cultural training |

| 96. Other services |

| 96.09.09. Personal service activities |

| AREA 1—Activities of Preservation and Enhancement of Historical and Artistic Heritage |

| R91. Libraries, archives, museums and other cultural activities |

| R91.01. Library and archives activities |

| 91.011. Dej.knjižnic |

| 91.012. Dej.arhivov |

| R91.02. Museums activities |

| R91.03. Operation of historical sites and buildings and similar visitor attractions |

| R91.04. Botanical and zoological gardens and nature reserves activities |

| AREA 2—Non-reproducible activities of cultural goods and services, as Performing and visual arts |

| R90. Creative, arts and entertainment activities |

| R90.01. Performing arts |

| R90.02. Support activities to performing arts |

| R90.03. Artistic creation |

| R90.04. Operation of arts facilities |

| R93. Sports activities and amusement and recreation activities |

| R93.21. Activities of amusement parks and theme parks |

| 93.29. Dej.marin |

| 93.292. Dej.smučarskih centrov |

| 93.299. D.n.dej.za prosti čas |

| AREA 3—Activities related to the production of cultural goods according to a logic of industrial repeatability, as cultural industries |

| J58. Publishing activities |

| J58.1. Publishing of books, periodicals and other publishing activities |

| 58.110. Izdajanje knjig |

| 58.120. Izdajanje imenikov in adresarjev |

| 58.130. Izdajanje časopisov |

| 58.140. Izdajanje revij idr.periodike |

| 58.190. Dr.založništvo |

| J58.2. Software publishing |

| 58.210. Izdajanje računalniških iger |

| 58.290. Dr.izdajanje programja |

| J59. Motion picture, video and television programme and music publishing activities |

| 59.110. Produkcija filmov,videofilmov,tv oddaj |

| 59.120. Postprod.dej.pri.filmih.,videof.,tv odd |

| 59.130. Distrib.filmov,videofilmov,tv oddaj |

| 59.140. Kinematografska dej. |

| 59.200. Snemanje in izdaj.zvočn.zap.in muzik. |

| J60. Programming and broadcasting activities |

| 60.100. Radijska dej |

| 60.200. Televizijska dej |

| J62—Computer programming, consultancy and related activities |

| J62.01. Computer programming activities |

| G47—Retail trade, except of motor vehicles and motorcycles |

| G47.61. Retail sale of books in specialised stores |

| G47.62. Retail sale of newspapers and stationery in specialised stores |

| 47.621. Trg.dr.prd.s časopisi in revijami |

| 47.622. Trg.dr.prd.s papirjem in pisalnimi potr. |

| G47.63. Retail sale of music and video recordings in specialised stores |

| AREA 4—Creative industries related to the world of services |

| G47—Retail trade, except of motor vehicles and motorcycles |

| 47.630. Trg.dr.prd.z glasbenimi in video zapisi |

| 47.782. Trg.dr.prd.z umetniškimi izd |

| J63—Information service activities |

| J63.1. Data processing, hosting and related activities; web portals |

| 63.110. Obdelava podatkov in s tem povezane dej |

| 63.120. Obratovanje spletnih portalov |

| J63.9. Other information service activities (News agencies) |

| 63.910. Dej.tiskovnih agencij |

| 63.990. Dr.informiranje |

| M70—Activities of head offices; management consultancy activities |

| 70.210. Dej.stikov z javnostjo |

| M72—Scientific research and development |

| 72.200. Raz.-razv.dej.v družbos.in humanistiki |

| M73—Advertising and market research |

| 73.200. Raziskovanje trga in javnega mnenja |

| M74. Other professional, scientific and technical activities |

| M74.1. Specialised design activities |

| M74.2. Photographic activities |

| M74.3. Translation and interpretation activities |

| N81—Services to buildings and landscape activities |

| 81.300. Urej.in vzdrž.zelenih površin in okolice |

| N82—Office administrative, office support and other business support activities |

| N82.3. Organisation of conventions and trade shows (including organisation of exhibitions) |

| P85—Education |

| R85.52. Cultural education |

| Business Organizational Forms | |

|---|---|

| Individual Firms | |

| Registrirani zasebni izvajalec raziskovalec | Registered private operator researcher |

| Samostojni podjetnik posameznik (s.p.) | Individual Private Entrepreneur (s.p.) |

| Samozaposleni v kulturi | Self-employed in culture |

| Samostojni novinar | Free-lance journalist |

| Private Company | |

| Društvo, zveza društev | Society, union of societies |

| Družba z neomejeno odgovornostjo (d.n.o.) | Unlimited Liability Company (d.n.o.) |

| Družba z omejeno odgovornostjo (d.o.o.) | Limited Liability Company (d.o.o.) |

| Gospodarska zbornica | Chamber of Commerce |

| Komanditna družba (k.d.) | Limited partnership (k.d.) |

| Nevladna organizacija | Non-government organization |

| Nosilec dopolnilne dejavnosti na kmetiji | Holder of supplementary activity on the farm |

| Podružnica tujega društva | A branch of a foreign society |

| Podružnica tujega podjetja | A branch of a foreign company |

| Zadruga (z.o.o.) | Cooperative (z.o.o.) |

| Gospodarsko interesno združenje (GIZ) | Economic Interest Grouping (GIZ) |

| Sklad | Fund |

| Študentska organizacija | Student organization |

| Zadruga (z.b.o.) | Cooperative (z.b.o.) |

| Public Company | |

| Upravni organ v sestavi | Administrative body/authority in composition |

| Delniška družba (d.d.) | Public limited company (d.d.) |

| Javni raziskovalni zavod | Public Research Institute |

| Narodnostna skupnost | Ethnic community |

| Skupnost zavodov | Association of institutions |

| Zavod | Institute |

| Javna agencija | Public agency |

| Javni sklad | Public fund |

| Javni zavod | Public institution |

| Mladinski svet | Youth council |

| Ustanova | Institution |

| Business Organizational Forms | |

|---|---|

| Individual Firms | |

| DI | Impresa individuale |

| SU | Societa’ a responsabilita’ limitata con unico socio |

| Private Company | |

| CL | Societa’ cooperativa a responsabilita limitata |

| CN | Societa’ consortile |

| CO | Consorzio |

| AA | Societa’ in accomandita per azioni |

| AC | Associazione |

| AE | Societa’ consortile in accomandita semplice |

| AI | Associazione impresa |

| AS | Societa’ in accomandita semplice |

| CC | Consorzio con attivita’ esterna |

| CE | Comunione ereditaria |

| CF | Consorzio fidi |

| CI | Societa’ cooperativa a responsabilita illimitata |

| EE | Ente ecclesiastico |

| AF | Altre forme |

| Public Company | |

| CM | Consorzio municipale |

| AL | Azienda speciale di ente locale |

| CR | Consorzio intercomunale |

| CZ | Consorzio di cui al dlgs 267/2000 |

| ED | Ente diritto pubblico |

| AM | Azienda municipale |

| AP | Azienda provinciale |

| AR | Azienda regionale |

| AT | Azienda autonoma statale |

| EC | Ente pubblico commerciale |

| CCI Business Sectors | Number of CCI Firms | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| FVG | SLO | VEN | |

| audiovisual sector | 3 | ||

| consultancy/services | 3 | 3 | |

| creative service providers | 2 | 2 | |

| cultural education | 1 | 1 | |

| cultural properties | 1 | ||

| fashion | 1 | 1 | |

| food industry | 1 | ||

| ict | 1 | ||

| visual and performing arts | 3 | 7 | 7 |

| marketing | 2 | ||

| membership organization | 4 | 1 | |

| science museum | 1 | ||

| Sub-regional total | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Total Interviewees | 45 | ||

References

- EC European Commission. Commission Recommendation C(2003) 1422 of 6 May 2003. In Concerning the Definition of Micro, Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises; Annex Article 2; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- EC European Commission. European Commission Green Paper—Unlocking the Potential of Cultural and Creative Industries; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- KEA European Affair. The Economy of Culture in Europe; Study Prepared for the European Commission—Directorate-General for Education and Culture; KEA: Brussels, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G.; Foord, J. European Funding of Culture: Promoting Common Culture or Regional Growth? Cult. Trends 1999, 9, 53–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions—A New European Agenda for Culture; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Valentino, P. L’impresa Culturale e Creativa. Verso una definizione condivisa. Econ. Della Cult. 2013, 3, 273–288. [Google Scholar]

- Purg, P.; Cacciatore, S.; Gerbec, J.Č. Establishing Ecosystems for Disruptive Innovation by Cross-Fertilizing Entrepreneurship and the Arts. Creat. Ind. J. 2021, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations—General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Howkins, J. The Creative Economy: How People Make Money from Ideas; Reprinted with updated material; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-0-14-028794-3. [Google Scholar]

- Joffe, A. The Integration of Culture in Sustainable Development. In Re-Shaping Cultural Policies: Advancing Creativity for Development [2018 Global Report on Second Monitoring the 2005 Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions]; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2017; ISBN 978-92-3-100256-4. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO; The World Bank. Cities, Culture, Creativity Leveraging Culture and Creativity for Sustainable Urban Development and Inclusive Growth; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-92-3-100452-0. [Google Scholar]

- EC European Commission. Commission Staff Working Document—Action Plan Accompanying the Document—Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions—Concerning the European Union Strategy for the Adriatic and Ionian Region; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- Gerlitz, L.; Prause, G.K. Cultural and Creative Industries as Innovation and Sustainable Transition Brokers in the Baltic Sea Region: A Strong Tribute to Sustainable Macro-Regional Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, P.; Ferilli, G.; Tavano Blessi, G. From Culture 1.0 to Culture 3.0: Three Socio-Technical Regimes of Social and Economic Value Creation through Culture, and Their Impact on European Cohesion Policies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flew, T.; Cunningham, S. Creative Industries after the First Decade of Debate. Inf. Soc. 2010, 26, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, A.C.; Nathan, M.; Rincon-Azar, A. Creative Economy Employment in the EU and the UK: A Comparative Analysis; Nesta: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission—Directorate General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture; IDEA Consult; KEA; imec SMIT VUB. Mapping the Creative Value Chains: A Study on the Economy of Culture in the Digital Age: Executive Summary; EU Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2017.

- European Commission—Joint Research Centre. The Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor: 2019 Edition; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2019.

- UNESCO. Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- HKU Hogeschool vor de Kunsten. The Entrepreneurial Dimension of the Cultural and Creative Industries (Study Prepared for the European Commission—Directorate General for Education and Culture); HKU: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD; UNDP. Creative Economy Report; UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- ESSnet-CULTURE. European Statistical System Network on Culture—Final Report; ESSnet-Culture Project Coordinator: Luxembourg, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Clifton, N.; Chapain, C.; Comunian, R. (Eds.) Creative Regions in Europe; First issued in paperback; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-138-39249-6. [Google Scholar]

- Crociata, A. Measuring Creative Economies: A Critical Review of CCIs; DISCE—Developing Inclusive and Sustainable Creative Economies: 2020. Available online: https://disce.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/DISCE-Report-D2.1.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Scott, A.J. Cultural-Products Industries and Urban Economic Development: Prospects for Growth and Market Contestation in Global Context. Urban Aff. Rev. 2004, 39, 461–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P. Creative Cities and Economic Development. Urban Stud. 2000, 37, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.J. The Cultural Economy of Cities. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 1997, 21, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, C. The Creative City: A Toolkit for Urban Innovators, 2nd ed.; Comedia: New Stroud, UK; Earthscan: London, UK; Sterling, VA, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-1-84407-599-7. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M. Interruptions: Testing the Rhetoric of Culturally Led Urban Development. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 889–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santagata, W. Cultural Districts, Property Rights and Sustainable Economic Growth. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2002, 26, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heur, B. The Clustering of Creative Networks: Between Myth and Reality. Urban Stud. 2009, 46, 1531–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, E.J.; Bamford, J.; Saynor, P. (Eds.) Small Firms and Industrial Districts in Italy; Routledge Library Editions. Small business; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bartol, B. Strategija Prostorskega Razvoja Slovenije: SPRS; Ministrstvo za Okolje, Prostor in Energijo, Direktorat za Prostor, Urad za Prostorski Razvoj: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2004.

- Zavodnik Lamovšek, A.; Drobne, S.; Žaucer, T. Small and Medium-Size Towns as the Basis of Polycentric Urban Development. Geod. Vestn.—Assoc. Surv. Slov. 2008, 52, 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Allcock, J.B.; Gosar, A.; Lavrencic, K.; Barker, T.M. Economy of Slovenia. In Britannica; Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.britannica.com/place/Slovenia/Economy (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Santagata, W. (Ed.) Libro Bianco Sulla Creatività: Per un Modello Italiano di Sviluppo, 1st ed.; Interazioni; Università Bocconi: Milano, Italy, 2009; ISBN 978-88-8350-146-3. [Google Scholar]

- Fondazione Symbola and Unioncamere. L’Italia Che Verrà. Industria Culturale, Made in Italy e Territori.; I Quaderni Symbola series; Fondazione Symbola and Unioncamere: Rome, Italy, 2011; Available online: https://www.symbola.net/ricerca/litalia-che-verra-industria-culturale-made-in-italy-e-territori (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Vaia, G.; Gritti, E. Report on CCI—Italy, COCO4CCI Interreg Central Europe, Deliverable D.T1.2.2 2019; Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Slovenia: Ljubljana, Sloenia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fondazione Symbola and Unioncamere Io Sono Cultura—Rapporto 2020; I Quaderni Symbola series; Fondazione Symbola and Unioncamere: Rome, Italy, 2021; Available online: https://www.symbola.net/ricerca/io-sono-cultura-2020 (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Etikan, I. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC European Commission. Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor—Venice; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium; Available online: https://composite-indicators.jrc.ec.europa.eu/cultural-creative-cities-monitor/countries-and-cities/venice (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- EC European Commission. Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor—Trieste; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium; Available online: https://composite-indicators.jrc.ec.europa.eu/cultural-creative-cities-monitor/countries-and-cities/trieste (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Murovec, N.; Kavaš, D.; Bartolj, T.; Celik, M. Statisticna Analiza Stanja Kulturnega in Kreativnega Sektorja v Sloveniji 2008–2017; Muzej za Arhitekturo in Oblikovanje (MAO), Center za Kreativnost (CZK): Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2020; ISBN 978-961-6669-67-2. [Google Scholar]

- EC European Commission. Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor—Ljubljana; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium; Available online: https://composite-indicators.jrc.ec.europa.eu/cultural-creative-cities-monitor/countries-and-cities/ljubljana (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- United Nations—General Assembly. Global Indicator Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and Targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Adopted by the General Assembly in A/RES/71/313 (Annex), Annual Refinements Contained in E/CN.3/2018/2 (Annex II), E/CN.3/2019/2 (Annex II), 2020 Comprehensive Review Changes (Annex II) and Annual Refinements (Annex III) Contained in E/CN.3/2020/2 and Annual Refinements (Annex) Contained in E/CN.3/2021/2; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Urban@it (Ed.) Sesto Rapporto Sulle Città: Le Città Protagoniste dello Sviluppo Sostenibile; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2021; ISBN 978-88-15-29146-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ministero della Transizione Ecologica; Ministero degli Affari Esteri e della Cooperazione Internazionale Voluntary National Review 2022, Italy|High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development. Available online: https://hlpf.un.org/countries/italy/voluntary-national-review-2022 (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Bonello, V.; Faraone, C.; Gambarotto, F.; Nicoletto, L.; Pedrini, G. Clusters in Formation in a Deindustrialized Area: Urban Regeneration and Structural Change in Porto Marghera (Venice). Compet. Rev. Int. Bus. J. 2020, 30, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonello, V.; Faraone, C.; Leoncini, R.; Nicoletto, L.; Pedrini, G. (Un)Making Space for Manufacturing in the City: The Double Edge of pro-Makers Urban Policies in Brussels. Cities 2022, 129, 103816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations—General Assembly. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017—71/313. Work of the Statistical Commission Pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Sustainable Development Goals | CCIs |

|---|---|

| SDG 8 ‘promoting sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all’ | |

| Target 8.3: Promote development-oriented policies that support productive activities, decent job creation, entrepreneurship, creativity and innovation, and encourage the formalization and growth of micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises, including through access to financial services. | 32.4. Video Games and toys production activities 58. Publishing activities 60. Radio and television programming and transmission activities 71. Architectural and engineering studios activities 73. Advertising and market research 74. other professional, scientific and technical activities 81. Buildings and landscape services 82. Support services for enterprises and offices 85. Education 90. Creative, artistic and entertainment activities 91. Artistic and historical heritage 93. Sport and leisure activities |

| Target 8.9: By 2030, devise and implement policies to promote sustainable tourism that creates jobs and promotes local culture and products | 91. Artistic and historical heritage 91.01. Libraries and archives 91.02. Museums 91.03. Management of historical sites and monuments 91.04. Activities of botanical gardens, zoos and natural reserves 93. Sport and leisure activities 93.21. Theaters, concert halls and other artistic structures management 93.29. Amusement parks and theme parks 93.29.1. Other recreational and entertainment activities 93.29.2. Discos, dance halls, night clubs and similar activities 93.29.9. Bathing establishments management: maritime, lake and river 93.29.9. Other entertainment and leisure activities 96.09.02. Hairdressers and other beauty treatments |

| SDG 11 ‘making cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable’ | |

| Target 11.3: By 2030, enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanization and capacity for participatory, integrated and sustainable human settlement planning and management in all countries. | 47. Retail sale (concerning CCIs products and services) 63. Information technology services 70. Management consultancies 71. Architectural and engineering studios activities 72. Scientific research and development 81. Buildings and landscape services 90.04. Management of artistic structures (theatres, musical concerts, etc.) 91.03. Management of historical sites and monuments 91.04. Activities of botanical gardens, zoos and natural reserves 93. Sport and leisure activities |

| Target 11.4: Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage. | 71. Architectural and engineering studios activities 74. other professional, scientific and technical activities 81. Buildings and landscape services 85. Education 91. Artistic and historical heritage |

| Target 11.7: By 2030, provide universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible, green and public spaces, in particular for women and children, older persons and persons with disabilities. | 71. Architectural and engineering studios activities 71.11. Architecture firms activities 71.12.2. Integrated engineering design services 72.2. Research and experimental development in the field of social sciences and humanities 81. Buildings and landscape services 81.3. Landscape care and maintenance 85. Education 91.01. Libraries and archives 91.02. Museums |

| Italy | Veneto | Province | Padova | Treviso | Verona | Vicenza | Venice | Rovigo | Belluno | Regional Total | Country Total |

| Firms n. | 3295 | 2594 | 2769 | 2436 | 2369 | 519 | 372 | 14,354 | 17,711 | ||

| Friuli Venezia Giulia | Province | Udine | Pordenone | Trieste | Gorizia | 3357 | |||||

| Firms n. | 1576 | 786 | 670 | 325 | |||||||

| Slovenia | Western Slovenia | Province | Ljubljana | Gorenjska | Obalno Kraška | Goriška | Primorsko-Notranjska | 17,339 | 17,339 | ||

| Firms n. | 11,877 | 2323 | 1391 | 1295 | 453 | ||||||

| CCI Firms by Activity Classification | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Heritage (Area 1) | 334 | 0.9 |

| Arts (Area 2) | 5971 | 16.7 |

| Cultural (Area 3) | 9933 | 27.7 |

| Services (Area 4) | 18,803 | 52.5 |

| Total | 35,803 |

| CCIs Classification | ||

|---|---|---|

| Firms size | Number | % |

| Large | 233 | 0.7 |

| Medium | 437 | 1.2 |

| Small | 1560 | 4.5 |

| Micro | 30,043 | 85.7 |

| Other | 2777 | 7.9 |

| Legal status | Number | % |

| Individual | 19,645 | 56.0 |

| Private | 14,173 | 40.4 |

| Public | 1087 | 3.1 |

| Not classified | 145 | 0.4 |

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|

|

| Opportunities | Threats |

|

|

| SDG | CCI Area Involved | Spatial Pattern as Policy Integration Element | Descriptors of Recommendations on Integrated Policies (Urban, Cultural, Tourism, Development) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDG 8 | |||

| Target 8.3 Promote development-oriented policies that support productive activities, decent job creation, entrepreneurship, creativity and innovation, and encourage the formalization and growth of micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises, including through access to financial services. | Area 1—Heritage Area 2—Art Area 3—Cultural Area 4—Services | Concentration around Urban Areas of Great Attraction and Agglomeration (Figure 11), Dispersed distribution following territorial layout—sprawl city and industrial districts (Figure 13), SWOT opportunities | Urban policies devoted to urban reactivation of dismissed productive areas and empty commercial premises located in strategic regional areas, and small and medium city centres should promote start-ups incubation and entrepreneurial approaches. |

| Concentration around Urban Areas of Great Attraction and Agglomeration (Figure 11) | Cultural policies could involve craftsmanship and SMEs activities through cultural institutions action located in city centres putting forward programmes aiming at promoting successful entrepreneurial stories from dispersed territories. | ||

| Dispersed distribution following territorial layout—Sprawl city and industrial districts (Figure 13) | Development policies aiming at fostering industrial competitiveness should take into account dispersed CCIs spatial distribution and work jointly with welfare policies and policies devoted to mobility infrastructure and services in order to attract more informal enterprises from cultural and creative sectors, seen as profiting and enabling to liaison with SMEs. | ||

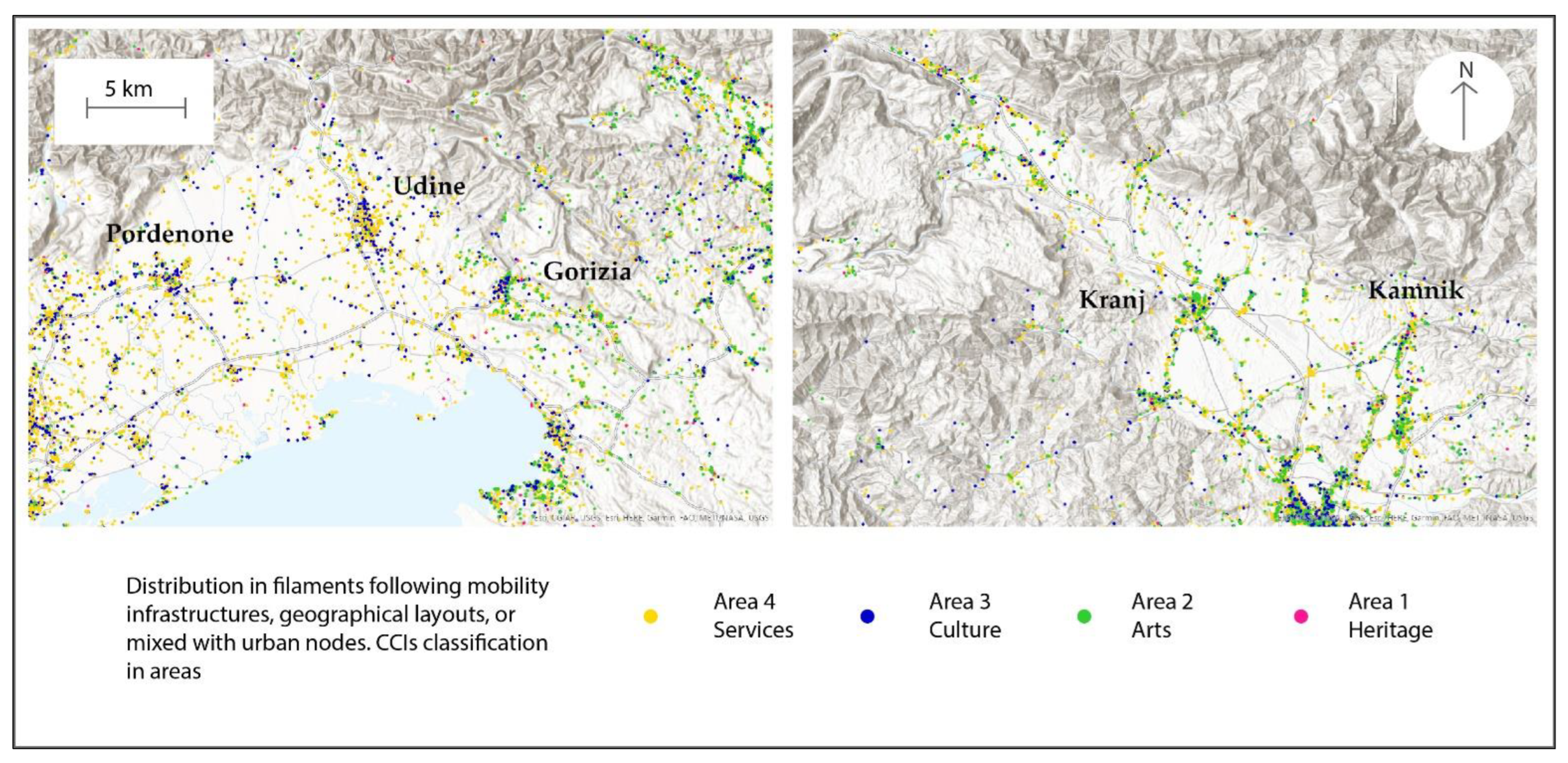

| Target 8.9 By 2030, devise and implement policies to promote sustainable tourism that creates jobs and promotes local culture and products. | Area 1—Heritage Area 2—Art Area 3—Cultural | Distribution in filaments following mobility infrastructures, geographical layouts, or mixed with urban nodes (Figure 12) | Cultural policies should include in slow tourism routes formerly dismissed buildings and spaces (from production and services premises) and reused as sites for CCIs-SMEs collaborations that would offer new opportunities for product showcasing and selling. |

| Dispersed distribution following territorial layout: (Figure 13) | Fostering the creation of collaborations oriented towards the upgrading and innovation of traditional manufacturing and craftsmanship based on material and human resources of existing production sites (districts/clusters) in order to sustain local culture and products, built environment and material heritage. | ||

| SDG 11 | |||

| Target 11.3 By 2030, enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanization and capacity for participatory, integrated and sustainable human settlement planning and management in all countries. | Area 1—Heritage Area 2—Art Area 4—Services | Concentration around Urban Areas of Great Attraction and Agglomeration (Figure 11) Distribution in filaments following mobility infrastructures, geographical layouts, or mixed with urban nodes (Figure 12) | Urban policy oriented towards territorial renewal and urban regeneration should take into account reuse of urban spaces and premises through CCIs and SMEs settlement, their close proximity, and their matching/collaboration, in synergy with industrial development policies. |

| Distribution in filaments following mobility infrastructures, geographical layouts, or mixed with urban nodes (Figure 12). Dispersed distribution following territorial layout (Figure 13). | Cultural and development policies should consider stakeholders’ settlement/localization choices, and stimulate through funding/subsidies CCIs and SMEs willing to set up in reused and mixed-use premises. | ||

| Concentration around Urban Areas of Great Attraction and Agglomeration (Figure 11). Distribution in filaments following mobility infrastructures, geographical layouts, mixed with urban nodes (Figure 12). Dispersed distribution following territorial layout (Figure 13) | Urban policies oriented towards the implementation of urban regeneration processes should involve both traditional production and cultural and creative stakeholders into participating and acting, both in individual and groups capacity, with formal or informal setups. | ||

| Dispersed distribution following territorial layout such as industrial districts and sprawled urbanisation (Figure 13) | Urban policies addressing bottom-up urban transformation processes lead by CCIs/SMEs collaborations should sustain them through plans and schemes considering urban services and public mobility provision, while ameliorating wider public infrastructure. | ||

| Target 11.4: Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage | Area 1—Heritage Area 3—Cultural Area 4—Services | Concentration around Urban Areas of Great Attraction and Agglomeration (Figure 11) | Preservation policies should be more integrated with urban policies related to land/building use, to promptly address the reuse of built heritage by CC sectors, and avoid the phenomenon of abandoned built heritage. |

| Concentration around Urban Areas of Great Attraction and Agglomeration (Figure 11). Distribution in filaments following mobility infrastructures, geographical layouts, or mixed with urban nodes (Figure 12). Dispersed distribution following territorial layout (Figure 13) | Preservation and urban policies should work together in order to reallocate the new needs for space put forward by CCIs and SMEs in terms of square metres requirements, and accessibility, in order to contain further land exploitation and preserve natural heritage, in this sense central locations (both in urban and rural setups) are ideal. | ||

| Distribution in filaments following mobility infrastructures, geographical layouts, or mixed with urban nodes (Figure 12) | Cultural policies should favour CCIs-SMEs that are fostering and valorizing cultural and natural heritage, such as territory and geographical history, historical productions and fragile ecosystems while innovating their protection through story-telling and digital devices. | ||

| Distribution in filaments following mobility infrastructures, geographical layouts, or mixed with urban nodes (Figure 12) | Cultural policies and tourism policies should address issues of overcrowded attendance of cultural and natural heritage through funding CCIs-SMEs collaboration into setting up new routes. | ||

| Target 11.7: By 2030, provide universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible, green and public spaces, in particular for women and children, older persons and persons with disabilities. | Area 1—Heritage Area 4—Services | Concentration around Urban Areas of Great Attraction and Agglomeration (Figure 11). Distribution in filaments following mobility infrastructures, geographical layouts, or mixed with urban nodes (Figure 12) | Promoting cultural policies favouring CCIs-SMEs collaboration in products and services aiming to enrich public or collective open spaces and services, with devices for transgenerational targets (children and older people). |

| Dispersed distribution following territorial layout (Figure 13) | Development policies should favour CCIs-SMEs collaborations favouring the ones aiming at recovering dismissed industrial areas, to render them accessible urban spaces with also public programs useful to all. | ||

| Concentration around Urban Areas of Great Attraction and Agglomeration (Figure 11) Distribution in filaments following mobility infrastructures, geographical layouts, or mixed with urban nodes (Figure 12) | Urban policies addressing public and green spaces accessibility should support CCIs and SMEs collaborations aiming at rendering them accessible for persons using wheelchairs or parents with baby buggies. | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Faraone, C. Territorial Challenges for Cultural and Creative Industries’ Contribution to Sustainable Innovation: Evidence from the Interreg Ita-Slo Project DIVA. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11271. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811271

Faraone C. Territorial Challenges for Cultural and Creative Industries’ Contribution to Sustainable Innovation: Evidence from the Interreg Ita-Slo Project DIVA. Sustainability. 2022; 14(18):11271. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811271

Chicago/Turabian StyleFaraone, Claudia. 2022. "Territorial Challenges for Cultural and Creative Industries’ Contribution to Sustainable Innovation: Evidence from the Interreg Ita-Slo Project DIVA" Sustainability 14, no. 18: 11271. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811271