Understanding Chinese EFL Learners’ Acceptance of Gamified Vocabulary Learning Apps: An Integration of Self-Determination Theory and Technology Acceptance Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- Identify Chinese college EFL learners’ motivation to use gamified English vocabulary learning apps and their perceptions about them;

- (2)

- Explain how users’ motivations affect their perceptions in terms of app adoption;

- (3)

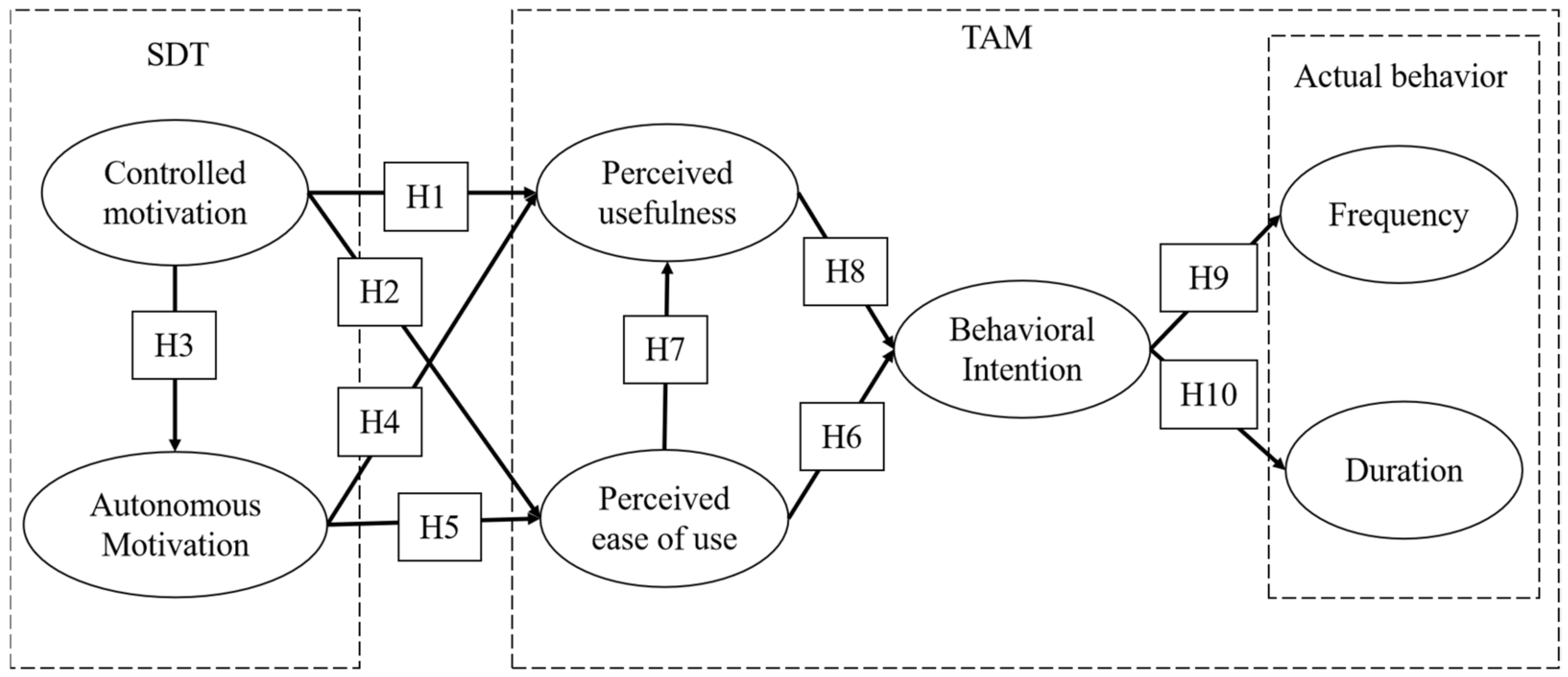

- Develop an integrative model about the antecedents of the use of the apps among Chinese EFL learners by combing the self-determination theory (SDT) and the technology acceptance model (TAM).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Self-Determination Theory

2.2. Technology Acceptance Model

2.3. Hypothesis Development

3. Research Methods

3.1. Measurement Instruments

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Participants

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Model Evaluation

4.3. Structural Model Examination

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.2. Limitations and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than once a week | Once a week | 2–3 times a week | 4–5 times a week | At least once everyday |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 h | ≥1 h, <3 h | ≥3 h, <5h | ≥5 h, <7 h | ≥7 h |

References

- Wilkins, D.A. Linguistics in Language Teaching; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; King, R.B.; Wang, C. Adaptation and validation of the vocabulary learning motivation questionnaire for Chinese learners: A construct validation approach. System 2022, 108, 102853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nation, I.S. Learning Vocabulary in Another Language; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Deterding, S.; Khaled, R.; Nacke, L.; Dixon, D. Gamification: Toward a definition. In CHI 2011 Gamification Workshop Proceedings; ACM: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2011; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Klimova, B. Evaluating impact of mobile applications on EFL university learners’ vocabulary learning—A review study. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 184, 859–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikhart, M. Human-computer interaction in foreign language learning apps: Applied linguistics viewpoint of mobile learning. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 184, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakıroğlu, Ü.; Başıbüyük, B.; Güler, M.; Atabay, M.; Yılmaz Memiş, B. Gamifying an ICT course: Influences on engagement and academic performance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hew, K.F.; Huang, B.; Chu, K.W.S.; Chiu, D.K.W. Engaging Asian students through game mechanics: Findings from two experiment studies. Comput. Educ. 2016, 92–93, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Meng, Z.; Tian, M.; Zhang, Z.; Xiao, W. Modelling Chinese EFL learners’ flow experiences in digital game-based vocabulary learning: The roles of learner and contextual factors. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2021, 34, 483–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekler, E.D.; Brühlmann, F.; Tuch, A.N.; Opwis, K. Towards understanding the effects of individual gamification elements on intrinsic motivation and performance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 71, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muszyńska, K. Gamification of communication and documentation processes in project teams. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 176, 3645–3653. [Google Scholar]

- Giráldez, V.A.; Sanmiguel-Rodríguez, A.; Álvarez, O.R.; Navarro-Patón, R. Can gamification influence the academic performance of students? System 2022, 14, 5115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xia, Q.; Chu, S.K.W.; Yang, Y. Using gamification to facilitate students’ self-regulation in E-learning: A case study on students’ L2 English learning. System 2022, 14, 7008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- College Foreign Language Teaching Steering Committee. College English Teaching Guide; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Dai, W. Rote memorization of vocabulary and vocabulary development. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2011, 4, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yuan, Y. Empirical study on the mobile app-aided college English vocabulary teaching. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2019, 11, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Handbook of Self-Determination Research; University Rochester Press: Rochester, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, J.L.; Bureau, J.; Guay, F.; Chong, J.X.; Ryan, R.M. Student motivation and associated outcomes: A meta-analysis from self-determination theory. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 16, 1300–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Abraham, C.; Bond, R. Psychological correlates of university students’ academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 138, 353–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEown, M.S.; Noels, K.A.; Saumure, K.D. Students’ self-determined and integrative orientations and teachers’ motivational support in a Japanese as a foreign language context. System 2014, 45, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pae, T.I. Second language orientation and self-determination theory: A structural analysis of the factors affecting second language achievement. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 27, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, K.J.; Ntoumanis, N.; Mouratidis, A.; Katartzi, E.; Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C.; Vlachopoulos, S. Beware of your teaching style: A school-year long investigation of controlling teaching and student motivational experiences. Learn. Instr. 2018, 53, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, A.; Michou, A.; Aelterman, N.; Haerens, L.; Vansteenkiste, M. Begin-of-school-year perceived autonomy-support and structure as predictors of endof-school-year study efforts and procrastination: The mediating role of autonomous and controlled motivation. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 38, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeno, L.M.; Danielsen, A.G.; Raaheim, A. A Prospective investigation of students’ academic achievement and dropout in higher education: A selfdetermination theory approach. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 38, 1163–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y. An empirical study on English learning motivation of non-English majors—Taking Chinese university of science and technology as an example. Educ. Rev. 2012, 5, 108–110. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, L.A.; Johnson, M.A. Interdependent effects of autonomous and controlled regulation on exercise behavior. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2018, 44, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouratidis, A.; Michou, A.; Sayil, M.; Altan, S. It is autonomous, not controlled motivation that counts: Linear and curvilinear relations of autonomous and controlled motivation to school grades. Learn. Instr. 2021, 73, 101433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangunic, N.; Granic, A. Technology acceptance model: A literature review from 1986 to 2013. Univ. Access. Inf. Soc. 2015, 14, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Chen, C.; Wang, J. The effects of psychological ownership and TAM on social media loyalty: An integrated model. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 959–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, R.; Elouadi, A.E.; Hamdoune, A.; Choujtani, K.; Chati, A. TAM-UTAUT and the acceptance of remote healthcare technologies by healthcare professionals: A systematic review. Inform. Med. 2022, 32, 101008. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.C. Factors influencing the adoption of internet banking: An integration of TAM and TPB with perceived risk and perceived benefit. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2009, 8, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natasia, S.R.; Wiranti, Y.T.; Parastika, A. Acceptance analysis of NUADU as e-learning platform using the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) approach. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 197, 512–520. [Google Scholar]

- Chintalapati, N.; Srinivas, V.; Daruri, K. Examining the use of YouTube as a Learning Resource in higher education: Scale development and validation of TAM model. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, M.H.; Ahmad, M.B.; Shaari, Z.H.; Jannat, T. Integration of TAM, TPB, and TSR in understanding library user behavioral utilization intention of physical vs. E-book format. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2021, 47, 102399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukendro, S.; Habibi, A.; Khaeruddin, K.; Indrayana, B.; Syahruddin, S.; Makadada, F.A.; Hakim, H. Using an extended technology acceptance model to understand students’ use of e-learning during COVID-19: Indonesian sport science education context. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, H.; Almagrabi, A.O.; Shamim, A.; Anwar, F.; Bashir, A.K. Investigating the acceptance of mobile library applications with an extended technology acceptance model (TAM). Comput. Educ. 2020, 145, 103732. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.G.; Woo, E. Consumer acceptance of a quick response (QR) code for the food traceability system: Application of an extended technology acceptance model (TAM). Food. Res. Int. 2016, 85, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Tsai, J.L. Determinants of behavioral intention to use the Personalized Location-based Mobile Tourism Application: An empirical study by integrating TAM with ISSM. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2017, 96, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, R.; Siddiq, F.; Tondeur, J. The technology acceptance model (TAM): A meta-analytic structural equation modeling approach to explaining teachers’ adoption of digital technology in education. Comput. Educ. 2019, 128, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X. Online social networking sites continuance intention: A model comparison approach. J. Comput. Inform. Sys. 2016, 57, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosli, M.S.; Saleh, N.S. Technology enhanced learning acceptance among university students during COVID-19: Integrating the full spectrum of self-determination theory and self-efficacy into the technology acceptance model. Curr. Psychol. 2022. online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, F.; Sahin, Y.L. Drivers of technology adoption during the COVID-19 pandemic: The motivational role of psychological needs and emotions for pre-service teachers. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2022. online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isabel, B.; Catalán, S.; Martínez, E. Understanding applicants’ reactions to gamified recruitment. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 110, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Chen, X. Continuance intention to use MOOCs: Integrating the technology acceptance model (TAM) and task technology fit (TTF) model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 67, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Sivo, S. Predicting continued use of online teacher professional development and the influence of social presence and sociability. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2012, 43, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estriegana, R.; Medina-Merodio, J.A.; Barchino, R. Student acceptance of virtual laboratory and practical work: An extension of the technology acceptance model. Comput. Educ. 2019, 135, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, F.; Ward, R.; Ahmed, E. Investigating the influence of the most commonly used external variables of TAM on students’ Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) and Perceived Usefulness (PU) of e-portfolios. Comput. Hum. Behavi. 2016, 63, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, H.W.; Azlan, A. Factors influencing foreign language learners’ motivation in continuing to learn Mandarin. J. Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qi, J.; Shu, H. Review of relationships among variables in TAM. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2008, 13, 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- Granic, A.; Marangunic, N. Technology acceptance model in educational context: A systematic literature review. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2019, 50, 2572–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Prieto, J.C.; Olmos-Migueláñez, S.; García-Peñalvo, F.J. Do mobile technologies have a place in universities? The TAM model in higher education. In Handbook of Research on Mobile Devices and Applications in Higher Education Settings; Laura, B., Juan, A.J., Francisco, J.G., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2016; pp. 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R.; Leng, N.S.; Yusoff, R.C.M.; Samy, G.N.; Masrom, S.; Rizman, Z.I. E-learning acceptance based on technology acceptance model (TAM). J. Fund. Appl. Sci. 2017, 9, 871–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alraimi, K.M.; Zo, H.; Ciganek, A.P. Understanding the MOOCs continuance: The role of openness and reputation. Comput. Educ. 2015, 80, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Zheng, C.; Zeng, P.; Zhou, B.; Lei, L.; Wang, P. Using the theory of planned behavior and the role of social image to understand mobile English learning check-in behavior. Comput. Educ. 2020, 156, 103942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, T.H.; Chen, Y.Y. With good we become good: Understanding e-learning adoption by theory of planned behavior and group influences. Comput. Educ. 2016, 92–93, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Connell, J.P. Perceived locus of causality and internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Y.J.; So, H.J.; Kim, N.H. Examination of relationships among students’ self-determination, technology acceptance, satisfaction, and continuance intention to use K-MOOCs. Comput. Educ. 2018, 122, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhou, T.; Wang, B. Exploring Chinese users’ acceptance of instant messaging using the theory of planned behavior, the technology acceptance model, and the flow theory. Comput. Hum. Behavi. 2009, 25, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.W.; Kim, Y.G. Extending the TAM for a World-Wide-Web context. Inform. Manag. 2001, 38, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural equation modeling with AMOS, EQS, and LISREL: Comparative approaches to testing for the factorial validity of a measuring instrument. Int. J. Test. 2001, 1, 55–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equat. Mode. Mul. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.W.; Stone, R.W. A structural equation model of end-user satisfaction with a computer-based medical information system. Inform. Resour. Manag. J. 1994, 7, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Canonical correlation analysis as a special case of a structural relations model. Multivariate. Behav. Res. 1981, 16, 437–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulland, J. Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3094025 (accessed on 11 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Park, N.; Jung, Y.; Lee, K.M. Intention to upload video content on the internet: The role of social norms and ego-involvement. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 1996–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangur, S.; Ercan, I. Comparison of model fit indices used in structural equation modeling under multivariate normality. J. Mod. Appl. Stat. Methods 2015, 14, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, R.W.Y.; Lam, S.F. The interaction between social goals and self-construal on achievement motivation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 38, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, V.Y.; Hong, Y.Y. When academic achievement is an obligation: Perspectives from social-oriented achievement motivation. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2014, 45, 110–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacella, D.; López-Pérez, B. Assessing children’s interpersonal emotion regulation with virtual agents: The serious game emodiscovery. Comput. Educ. 2018, 123, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesien, M.; Rodriguez, A.; Rey, B.; Alcaniz, M.; Banos, R.M.; Ma, D.V. How the physical similarity of avatars can influence the learning of emotion regulation strategies in teenagers. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 43, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosendo-Rios, V.; Trott, S.; Shukla, P. Systematic literature review online gaming addiction among children and young adults: A framework and research agenda. Addict. Behav. 2022, 129, 107238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; King, R.B.; Rao, N. The role of social-academic goals in Chinese students’ self-regulated learning. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2019, 34, 579–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, A.W.; Ward, M.K.; Allred, C.M.; Pappalardo, G.; Stoughton, J.W. Careless response and attrition as sources of bias in online survey assessments of personality traits and performance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 76, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Number | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 165 | 60.66% |

| Female | 107 | 39.34% | |

| Age | 18–22 | 250 | 91.91% |

| >22 | 22 | 8.09% | |

| Major | Science | 35 | 12.87% |

| Technology | 106 | 38.97% | |

| Engineering | 103 | 37.87% | |

| Mathematics | 28 | 10.29% | |

| Years of Study | Freshman | 49 | 18.01% |

| Sophomore | 72 | 26.47% | |

| Junior | 98 | 36.03% | |

| Senior | 53 | 19.49% | |

| Usage Frequency | Less than once a week | 6 | 2.21% |

| Once a week | 10 | 3.68% | |

| 2–3 times a week | 88 | 32.35% | |

| 4–5 times a week | 91 | 33.46% | |

| At least once everyday | 77 | 28.31% | |

| Hours spent per Week | <1 h | 57 | 20.96% |

| ≥1 h, <3 h | 137 | 50.37% | |

| ≥3 h, <5h | 47 | 17.28% | |

| ≥5 h, <7 h | 19 | 6.99% | |

| ≥7 h | 12 | 4.41% |

| Construct | CM | AM | PU | PEOU | AVE | √AVE | CR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM | 0.665 | 0.815 | 0.922 | 0.992 | ||||

| AM | 0.091 | 0.654 | 0.809 | 0.918 | 0.919 | |||

| PU | 0.470 | 0.370 | 0.591 | 0.769 | 0.806 | 0.811 | ||

| PEOU | 0.095 | 0.358 | 0.473 | 0.87 | 0.933 | 0.918 | 0.691 | |

| BI | 0.45 | 0.307 | 0.362 | 0.397 | 0.584 | 0.764 | 0.807 | 0.808 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Coefficient | S.E. | T-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | CM→PU | 0.453 | 0.056 | 7.507 *** |

| H2 | CM→PEOU | 0.087 | 0.058 | 1.431 ns |

| H3 | CM→AM | 0.127 | 0.064 | 1.925 ns |

| H4 | AM→PU | 0.312 | 0.065 | 4.614 *** |

| H5 | AM→PEOU | 0.493 | 0.066 | 7.360 *** |

| H6 | PEOU→BI | 0.430 | 0.058 | 5.814 *** |

| H7 | PU→PEOU | 0.270 | 0.067 | 3.908 *** |

| H8 | PU→BI | 0.448 | 0.061 | 5.850 *** |

| H9 | BI→Frequency | 0.627 | 0.104 | 9.255 *** |

| H10 | BI→Duration | 0.503 | 0.106 | 7.501 *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Zhao, S. Understanding Chinese EFL Learners’ Acceptance of Gamified Vocabulary Learning Apps: An Integration of Self-Determination Theory and Technology Acceptance Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11288. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811288

Chen Y, Zhao S. Understanding Chinese EFL Learners’ Acceptance of Gamified Vocabulary Learning Apps: An Integration of Self-Determination Theory and Technology Acceptance Model. Sustainability. 2022; 14(18):11288. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811288

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yang, and Shuang Zhao. 2022. "Understanding Chinese EFL Learners’ Acceptance of Gamified Vocabulary Learning Apps: An Integration of Self-Determination Theory and Technology Acceptance Model" Sustainability 14, no. 18: 11288. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811288

APA StyleChen, Y., & Zhao, S. (2022). Understanding Chinese EFL Learners’ Acceptance of Gamified Vocabulary Learning Apps: An Integration of Self-Determination Theory and Technology Acceptance Model. Sustainability, 14(18), 11288. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811288