Leadership and Work Engagement Effectiveness within the Technology Era

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Work Engagement

2.2. The Leadership Process

2.3. Entrepreneurial Leadership Behavior and Work Engagement

2.4. Entrepreneurial Leadership and Autonomy

2.5. Entrepreneurial Leadership and Social Support

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Methods Settings and Sample

3.3. Measures

3.4. Research Methodology

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Study Limitations and Directions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

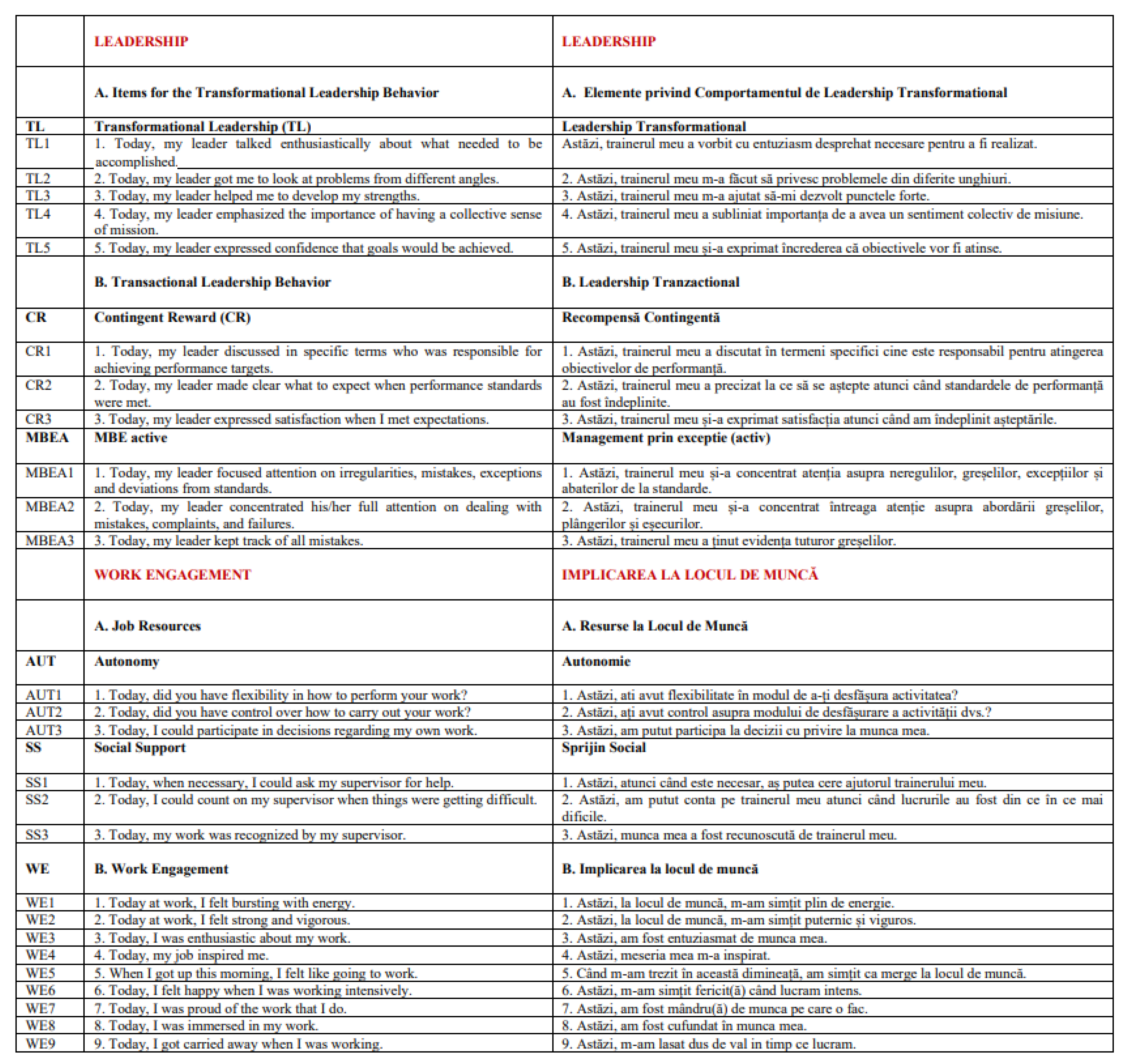

Appendix A

References

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Transformational leadership and organizational culture. Int. J. Public Adm. 1994, 17, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geier, M.T. Leadership in extreme contexts: Transformational leadership, performance beyond expectations? J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2016, 23, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Piccolo, R.F. Transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-analytic test of their relative validity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breevaart, K.; Hetland, J.; Demerouti, E.; Olsen, O.; Espevik, R. Daily transactional and transformational leadership and daily employee engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 87, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Xanthopoulou, D. Do transformational leaders enhance their followers’ daily work engagement? Leadersh. Q. 2011, 22, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Liao, Z.; Yam, K.C.; Johnson, R. Shared leadership: A state-of-the-art review and future research agenda. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 834–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila-Vázquez, G.; Castro-Casal, C.; Alvarez-Perez, D.; Rio, M. Promoting the sustainability of organizations: Contribution of transformational leadership to job engagement. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakis, J.; Atwater, L. Leader distance: A review and a proposed theory. In Leadership Perspectives; Taylor & Francis Group: Singapore, 2017; pp. 129–160. [Google Scholar]

- Avolio, B.J.; Bass, B.M. Individual consideration viewed at multiple levels of analysis: A multi-level framework for examining the diffusion of transformational leadership. Leadersh. Q. 1995, 6, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, D.V. (Ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Leadership and Organizations; Oxford Library of Psychology: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Antonakis, J.; Day, V.D. Leadership: Past, Present, and Future; Sage Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M.; Riggio, R.E. Transformational Leadership; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart Loane, S.; Webster, C.M.; D’Alessandro, S. Identifying consumer value co-created through social support within online health communities. J. Macromarket. 2015, 35, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Riggio, R.E. Transformational leadership theory. In Organizational Behavior I. Essential Theories of Motivation and Leadership; M.E. Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 361–385. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, J. Transformational leadership: An evolving concept examined through the works of Burns, Bass, Avolio, and Leithwood. Can. J. Educ. Adm. Policy 2006, 54, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A.; Piccolo, R.F.; Kosalka, T. The bright and dark sides of leader traits: A review and theoretical extension of the leader trait paradigm. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 855–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeflea, F.V.; Danciulescu, D.; Sitnikov, C.S.; Filipeanu, D.; Park, J.O.; Tugui, A. Societal Technological Megatrends: A Bibliometric Analysis from 1982 to 2021. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, F.; Wei, L.; Nurunnabi, M.; Subhan, Q.; Syed, I.; Fallatah, S. The impact of transformational leadership on job performance and CSR as mediator in SMEs. Sustainability 2019, 11, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S.; Pundt, A. Leader-member exchange from a job-stress perspective. In The Oxford Handbook of Leader-Member Exchange; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 189–208. [Google Scholar]

- Sadler, P. Leadership; Kogan Page Publishers: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Breevaart, F.; Mieloo, C.; Jahnsen, W.; Raat, H.; Donker, M.; Verhulst, F.; Van Oort, F. Ethnic differences in problem perception and perceived need for care for young children with problem behaviour. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 1063–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.; Salanova, M. Work engagement. Manag. Soc. Ethical Issues Organ. 2007, 135, 177. [Google Scholar]

- Ohly, S.; Sonnentag, S.; Niessen, C.; Zapf, D. Diary studies in organizational research: An introduction and some practical recommendations. J. Pers. Psychol. 2010, 9, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Han, S.J.; Park, J. Is the role of work engagement essential to employee performance or ‘nice to have’? Sustainability 2019, 11, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigol, T. Influence of authentic leadership on unethical pro-organizational behavior: The intermediate role of work engagement. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, S.L.; Green, C.R.; Marty, A. Meaningful work, job resources, and employee engagement. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.M. Leadership; Open Road Media: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kovjanic, S.; Schuh, S.C.; Jonas, K. Transformational leadership and performance: An experimental investigation of the mediating effects of basic needs satisfaction and work engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2013, 86, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. The impact of job crafting on job demands, job resources, and well-being. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breevaart, K.; Demerouti, E.; Sleebos, D.; Maduro, V. Uncovering the underlying relationship between transformational leaders and followers’ task performance. J. Pers. Psychol. 2014, 13, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCleskey, J.A. Situational, transformational, and transactional leadership and leadership development. J. Bus. Stud. Q. 2014, 5, 117. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl, G.; Mahsud, R. Why flexible and adaptive leadership is essential. Consult. Psychol. J. Pract. Res. 2010, 62, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smircich, L.; Morgan, G. Leadership: The management of meaning. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 1982, 18, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salancik, G.R.; Pfeffer, J. A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Adm. Sci. Q. 1978, 23, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.; Simcock, G.; Jenkins, L. The effect of social engagement on 24-month-olds’ imitation from live and televised models. Dev. Sci. 2008, 11, 722–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebenhüner, B.; Arnold, M. Organizational learning to manage sustainable development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2007, 16, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B. Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2010, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.B.; Einarsen, S. Outcomes of exposure to workplace bullying: A meta-analytic review. Work Stress 2012, 26, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.; Morten, H. The contribution of women on boards of directors: Going beyond the surface. Corp. Gov. 2010, 18, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, R.F.; Colquitt, J.A. Transformational leadership and job behaviors: The mediating role of core job characteristics. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, W.M.; Halbesleben, J.R.; Paul, J.R. If you’re close with the leader, you must be a brownnose: The role of leader–member relationships in follower, leader, and coworker attributions of organizational citizenship behavior motives. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2010, 20, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E.R.; LePine, J.A.; Rich, B.L. Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halbesleben, J.R. A meta-analysis of work engagement: Relationships with burnout, demands, resources, and consequences. Work Engagem. Handb. Essent. Theory Res. 2010, 8, 102–117. [Google Scholar]

- Rasool, S.F. How toxic workplace environment effects the employee engagement: The mediating role of organizational support and employee wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Xanthopoulou, D. The crossover of daily work engagement: Test of an actor–partner interdependence model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W. Reciprocal relationships between job resources, personal resources, and work engagement. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 74, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckey, M.R.; Bakker, A.B.; Dollard, F.M. Empowering leaders optimize working conditions for engagement: A multilevel study. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackoff, R.L. Transformational leadership. Strateg. Leadersh. 1999, 27, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Hetland, J.; Olsen, O.K.; Roar, E. Daily transformational leadership: A source of inspiration for follower performance? Eur. Manag. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hartog, D.N. Ethical leadership. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 409–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Defining and measuring work engagement: Bringing clarity to the concept. In Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2010; Volume 12, pp. 10–24. [Google Scholar]

- Seibert, S.E.; Wang, G.; Courtright, S.H. Antecedents and consequences of psychological and team empowerment in organizations: A meta-analytic review. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivasubramaniam, N.; Murry, W.; Avolio, B.; Jung, D. A longitudinal model of the effects of team leadership and group potency on group performance. Group Organ. Manag. 2002, 27, 66–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, F.; Abid, G.; Ilyas, S. Impact of ethical leadership on employee engagement: Role of self-efficacy and organizational commitment. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downton, J.V. Rebel Leadership: Commitment and Charisma in the Revolutionary Process; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bono, J.E.; Judge, T.A. Personality and transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.W. Strategies for Increasing Workforce Engagement. Doctoral Dissertation, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, A. What is leadership? J. Bus. Stud. Q. 2016, 8, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, D.I.; Sosik, J.J. Transformational leadership in work groups: The role of empowerment, cohesiveness, and collective-efficacy on perceived group performance. Small Group Res. 2002, 33, 313–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Pierce, W.D.; Cameron, J. Effects of reward on intrinsic motivation—Negative, neutral, and positive: Comment on Deci, Koestner, and Ryan. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M. Transformational leadership in education: A review of existing literature. Int. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2017, 93, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Givens, R.J. Transformational leadership: The impact on organizational and personal outcomes. Emerg. Leadersh. J. 2008, 1, 4–24. [Google Scholar]

- Reza, M.H. Components of transformational leadership behavior. EPRA Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2019, 5, 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, D.S.; Perrewé, P.L. The role of social support in the stressor-strain relationship: An examination of work-family conflict. J. Manag. 1999, 25, 513–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzion, D. Moderating effect of social support on the stress–burnout relationship. J. Appl. Psychol. 1984, 69, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrewé, P.L.; Carlson, D.S. Do men and women benefit from social support equally? Results from a field examination within the work and family context. In Gender, Work Stress, and Health; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Van Daalen, G.; Willemsen, T.M.; Sanders, K. Reducing work–family conflict through different sources of social support. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 69, 462–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Bass, R. The Bass Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research, and Managerial Applications; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Antonakis, J.; Bendahan, S.; Jacquart, P.; Lalive, R. On making causal claims: A review and recommendations. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 1086–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Stillwell, A.M.; Heatherton, T.F. Personal narratives about guilt: Role in action control and interpersonal relationships. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 17, 173–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B. Antecedents and consequences of work engagement: A multilevel nomological net. In A Research Agenda for Employee Engagement in a Changing World of Work; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021; pp. 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Regional for Development Agency. 2022. Available online: https://www.adrnordest.ro/en/our-story/evolution-and-continuous-transformation-since-1999/ (accessed on 7 January 2022).

- Bakker, A.B. The social psychology of work engagement: State of the field. Career Dev. Int. 2022, 27, 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallos, J.V. (Ed.) Business Leadership: A Jossey-Bass Reader; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmadani, V.G.; Schaufeli, W.; Stouten, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zulkarnain, Z. Engaging leadership and its implication for work engagement and job outcomes at the individual and team level: A multi-level longitudinal study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W.; Bakker, A.B. Dr Jekyll or Mr Hyde? On the differences between work engagement and workaholism. In Research Companion to Working Time and Work Addiction; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2006; Volume 193, pp. 192–217. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Verbeke, W. Using the job demands-resources model to predict burnout and performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 43, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finstad, K. Response interpolation and scale sensitivity: Evidence against 5-point scales. J. Usability Stud. 2010, 5, 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Johns, R. Likert items and scales. Surv. Quest. Bank: Methods Fact Sheet 2010, 1, 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, C.C.; Colman, A.M. Optimal number of response categories in rating scales: Reliability, validity, discriminating power, and respondent preferences. Acta Psychol. 2000, 104, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, J. Do data characteristics change according to the number of scale points used? An experiment using 5-point, 7-point and 10-point scales. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 50, 61–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Kale, S.; Chandel, S.; Pal, D. Likert scale: Explored and explained. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2015, 7, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L. A psychometric evaluation of 4-point and 6-point Likert-type scales in relation to reliability and validity. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1994, 18, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bycio, P.; Hackett, R.D.; Allen, J.S. Further assessments of Bass’s (1985) conceptualization of transactional and transformational leadership. J. Appl. Psychol. 1995, 80, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hartog, D.N.; Van Muijen, J.J.; Koopman, P.L. Transactional versus transformational leadership: An analysis of the MLQ. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1997, 70, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. Comment: Transformational leadership: Looking at other possible antecedents and consequences. J. Manag. Inq. 1995, 4, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakis, J.; Avolio, B.J.; Sivasubramaniam, N. Context and leadership: An examination of the nine-factor full-range leadership theory using the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. Leadersh. Q. 2003, 14, 261–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavusgil, S.T.; Das, A. Methodological issues in empirical cross-cultural research: A survey of the management literature and a framework. MIR Manag. Int. Rev. 1997, 37, 71–96. [Google Scholar]

- Purwanto, A. The Role of Digital Leadership, e-loyalty, e-service Quality and e-satisfaction of Indonesian E-commerce Online Shop. Int. J. Soc. Manag. Stud. 2022, 3, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Purwanto, A. The Role of Transformational Leadership and Organizational Citizenship Behavior on SMEs Employee Performance. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. Res. 2022, 3, 365–383. [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell, A.; Arnold, J. Self-perceived employability: Development and validation of a scale. Pers. Rev. 2007, 36, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudder, A.; Taber-Thomas, S.; Schaffner, K.; Pemberton, J.; Hunter, L.; Herschell, A. A mixed-methods study of system-level sustainability of evidence-based practices in 12 large-scale implementation initiatives. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2017, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.; Deckers, T.; Dohmen, T.; Falk, A.; Kosse, F. The relationship between economic preferences and psychological personality measures. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2012, 4, 453–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.-M.; Rai, A.; Ringle, C.M.; Völckner, F. Discovering Unobserved Heterogeneity in Structural Equation Models to Avert Validity Threats. MIS Q. 2013, 37, 665–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.N.; Khan, N.A. The nexuses between transformational leadership and employee green organisational citizenship behaviour: Role of environmental attitude and green dedication. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Alamer, A. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) in second language and education research: Guidelines using an applied example. Res. Methods Appl. Linguist. 2022, 1, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, N.F.; Cepeda-Carrion, G.; Roldan, J.; Ringle, C. European management research using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.N.; Liengaard, B.; Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C. Predictive model assessment and selection in composite-based modeling using PLS-SEM: Extensions and guidelines for using CVPAT. Eur. J. Mark. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kas, D.; Ahmad, F.; Thi, L.S. Measurement of transactional and transformational leadership: Validity and reliability in Sri Lankan context. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2014, 22, 559–574. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, J.M.; Rai, A.; Rigdon, E. Predictive validity and formative measurement in structural equation modeling: Embracing practical relevance. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 2013): Reshaping Society Through Information Systems Design, Milan, Italy, 15–18 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. Treating Unobserved Heterogeneity in PLS Path Modelling: A Comparison of FIMIX-PLS with Different Data Analysis Strategies. J. Appl. Stat. 2010, 37, 1299–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Radomir, L.; Moisescu, O.I.; Ringle, C.M. Latent Class Analysis in PLS-SEM: A Review and Recommendations for Future Applications. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 138, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Treating Unobserved Heterogeneity in PLS-SEM: A Multi-Method Approach. In Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Basic Concepts, Methodological Issues and Applications; Noonan, R., Latan, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 197–217. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M.A.; Ramayah, T.; Hwa, C.; Ting, H.; Chuah, F.; Cham, T.H. PLS-SEM statistical programs: A review. J. Appl. Struct. Equ. Model. 2021, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johari, J.; Mohd-Shamsudin, F.; Zainun, N.F.; Fee Yean, T.; Yahya, K. Institutional leadership competencies and job performance: The moderating role of proactive personality. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Matthews, L.; Ringle, C.M. Identifying and Treating Unobserved Heterogeneity with FIMIX-PLS: Part I—Method. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2016, 28, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Guidelines for Treating Unobserved Heterogeneity in Tourism Research: A Comment on Marques and Reis (2015). Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 57, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Bulters, A.J. The loss spiral of work pressure, work–home interference and exhaustion: Reciprocal relations in a three-wave study. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 64, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, C.; Johnson, M.D.; Herrmann, A.; Huber, F. Capturing Customer Heterogeneity Using a Finite Mixture PLS Approach. Schmalenbach Bus. Rev. 2002, 54, 243–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An Assessment of the Use of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling in Marketing Research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigdon, E.E.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Gudergan, S.P. Assessing Heterogeneity in Customer Satisfaction Studies: Across Industry Similarities and within Industry Differences. Adv. Int. Mark. 2011, 22, 169–194. [Google Scholar]

- Rigdon, E.E.; Schumacker, R.E.; Wothke, W. A comparative review of interaction and nonlinear modeling. In Interaction and Nonlinear Effects in Structural Equation Modeling; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, L.; Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M. Identifying and Treating Unobserved Heterogeneity with FIMIX-PLS: Part II—A Case Study. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2016, 28, 208–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigdon, E.E.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Structural Modeling of Heterogeneous Data with Partial Least Squares. In Review of Marketing Research; Malhotra, N.K., Ed.; Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 255–296. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Mooi, E.A. Response-Based Segmentation Using Finite Mixture Partial Least Squares: Theoretical Foundations and an Application to American Customer Satisfaction Index Data. Ann. Inf. Syst. 2010, 8, 19–49. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Becker, J.-M.; Ringle, C.M.; Schwaiger, M. Uncovering and Treating Unobserved Heterogeneity with FIMIX-PLS: Which Model Selection Criterion Provides an Appropriate Number of Segments? Schmalenbach Bus. Rev. 2011, 63, 34–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Schwaiger, M.; Ringle, C.M. Do We Fully Understand the Critical Success Factors of Customer Satisfaction with Industrial Goods?—Extending Festge and Schwaiger’s Model to Account for Unobserved Heterogeneity. J. Bus. Mark. Manag. 2009, 3, 185–206. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.; Hwa, C.; Ting, H.; Radomir, L.; Moisescu, O. Structural model robustness checks in PLS-SEM. Tour. Econ. 2020, 26, 531–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rigdon, E.E. Rethinking partial least squares path modeling: In praise of simple methods. Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloderer, M.P.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. The Relevance of Reputation in the Nonprofit Sector: The Moderating Effect of Socio-Demographic Characteristics. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2014, 19, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestian, A. Knowledge management concepts and models applicable in regional development. Manag. Mark. 2007, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, I.; Hou, F.; Zakari, A.; Irfan, M.; Muhammad, I.; Ahmad, M. Links among energy intensity, non-linear financial development, and environmental sustainability: New evidence from Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugui, A. Meta-Digital Accounting in the Context of Cloud Computing. In Encyclopedia of Information Science and Technology, 3rd ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PN, USA, 2015; pp. 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, H.M.; Chiu, W.C.K. Transformational leadership and job performance: A social identity perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2827–2835. [Google Scholar]

- Jyoti, J.; Bhau, S. Transformational leadership and job performance: A study of higher education. J. Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 77–110. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, F.-Y.; Tang, H.; Lu, S.K.; Lee, Y.C.; Lin, C.C. Transformational leadership and job performance: The mediating role of work engagement. Sage Open 2020, 10, 2158244019899085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yammarino, F.J. Indirect leadership: Transformational leadership at a distance. In Improving Organizational Effectiveness through Transformational Leadership; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 26–47. [Google Scholar]

- Alban-Metcalfe, R.J.; Alimo-Metcalfe, B. The transformational leadership questionnaire (TLQ-LGV): A convergent and discriminant validation study. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2000, 21, 280–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, D.V.; Antonakis, J. The future of leadership. In The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of the Psychology of Leadership, Change, and Organizational Development; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 221–235. [Google Scholar]

- Almutairi, D.O. The mediating effects of organizational commitment on the relationship between transformational leadership style and job performance. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 11, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeidat, B.Y.; Tarhini, A. A Jordanian empirical study of the associations among transformational leadership, transactional leadership, knowledge sharing, job performance, and firm performance: A structural equation modelling approach. J. Manag. Dev. 2016, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdinezhad, M.; Suandi, T.; Silong, A.; Omar, Z. Transformational, transactional leadership styles and job performance of academic leaders. Int. Educ. Stud. 2013, 6, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, D.; Suso-Ribera, C.; Fernández-Álvarez, J.; Cipresso, P.; Garcia-Palacios, A.; Riva, G.; Botella, C. Affect recall bias: Being resilient by distorting reality. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2020, 44, 906–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rullier, L.; Atzeni, T.; Husky, M.; Bouisson, J.; Dartigues, J.F.; Swendsen, J.; Bergua, V. Daily life functioning of community-dwelling elderly couples: An investigation of the feasibility and validity of Ecological Momentary Assessment. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2014, 23, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, G.; Buch, R.; Thompson, P.M.; Glasø, L. The impact of transformational leadership and interactional justice on follower performance and organizational commitment in a business context. J. Gen. Manag. 2021, 46, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberly, M.B.; Bluhm, D.; Guarana, C.; Avolio, B.; Hannah, S. Staying after the storm: How transformational leadership relates to follower turnover intentions in extreme contexts. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 102, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfredson, R.K.; Aguinis, H. Leadership behaviors and follower performance: Deductive and inductive examination of theoretical rationales and underlying mechanisms. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 558–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devviney, T.; Coltman, T.; Migley, D.; Venaik, S. Formative versus reflective measurement models: Two applications of formative measurement. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 1250–1262. [Google Scholar]

- Doty, D.H.; Glick, W.H. Common methods bias: Does common methods variance really bias results? Organ. Res. Methods 1998, 1, 374–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E. Method variance in organizational research: Truth or urban legend? Organ. Res. Methods 2006, 9, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Development and validation of the job crafting scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E. Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, D.; Krueger, A.B. Minimum Wages and Employment: A Case Study of the Fast Food Industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cronbach’s Alpha | rho_A | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUT | 0.895 | 0.896 | 0.895 | 0.74 |

| CR | 0.858 | 0.86 | 0.859 | 0.67 |

| JOB PERFORMANCE | 0.957 | 0.959 | 0.958 | 0.468 |

| JOB RESOURCES | 0.873 | 0.877 | 0.874 | 0.538 |

| Leadership | 0.931 | 0.935 | 0.932 | 0.556 |

| MBEA | 0.876 | 0.877 | 0.876 | 0.703 |

| SS | 0.819 | 0.819 | 0.818 | 0.6 |

| TL | 0.907 | 0.907 | 0.907 | 0.662 |

| Transactional leadership | 0.879 | 0.881 | 0.879 | 0.549 |

| WE | 0.948 | 0.951 | 0.949 | 0.698 |

| Work engagement | 0.943 | 0.947 | 0.944 | 0.532 |

| Column1 | Segment 1 | Segment 2 | Segment 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| AIC3 (modified AIC with Factor 3) | −6359.308 | −7547.157 | −7973.85 |

| CAIC (consistent AIC) | −6291.62 | −7407.551 | −7762.326 |

| EN (normed entropy statistic) | 0 | 0.931 | 0.834 |

| Summed Fit | −12650.928 | −14954.708 | −15736.176 |

| Segment 1 | Segment 2 | Segment 3 |

|---|---|---|

| 0.496 | 0.34 | 0.164 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gutu, I.; Agheorghiesei, D.T.; Tugui, A. Leadership and Work Engagement Effectiveness within the Technology Era. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11408. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811408

Gutu I, Agheorghiesei DT, Tugui A. Leadership and Work Engagement Effectiveness within the Technology Era. Sustainability. 2022; 14(18):11408. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811408

Chicago/Turabian StyleGutu, Ioana, Daniela Tatiana Agheorghiesei, and Alexandru Tugui. 2022. "Leadership and Work Engagement Effectiveness within the Technology Era" Sustainability 14, no. 18: 11408. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811408