Increasing Transparency in Global Supply Chains: The Case of the Fast Fashion Industry

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Extant Literature on Transparency in the Fashion Sector

2.1. Why Transparency?

2.2. Obstacles and Drivers of Transparency

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design and Data

3.2. Case Selection

3.3. Measure of the Dependent Variable (Transparency)

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

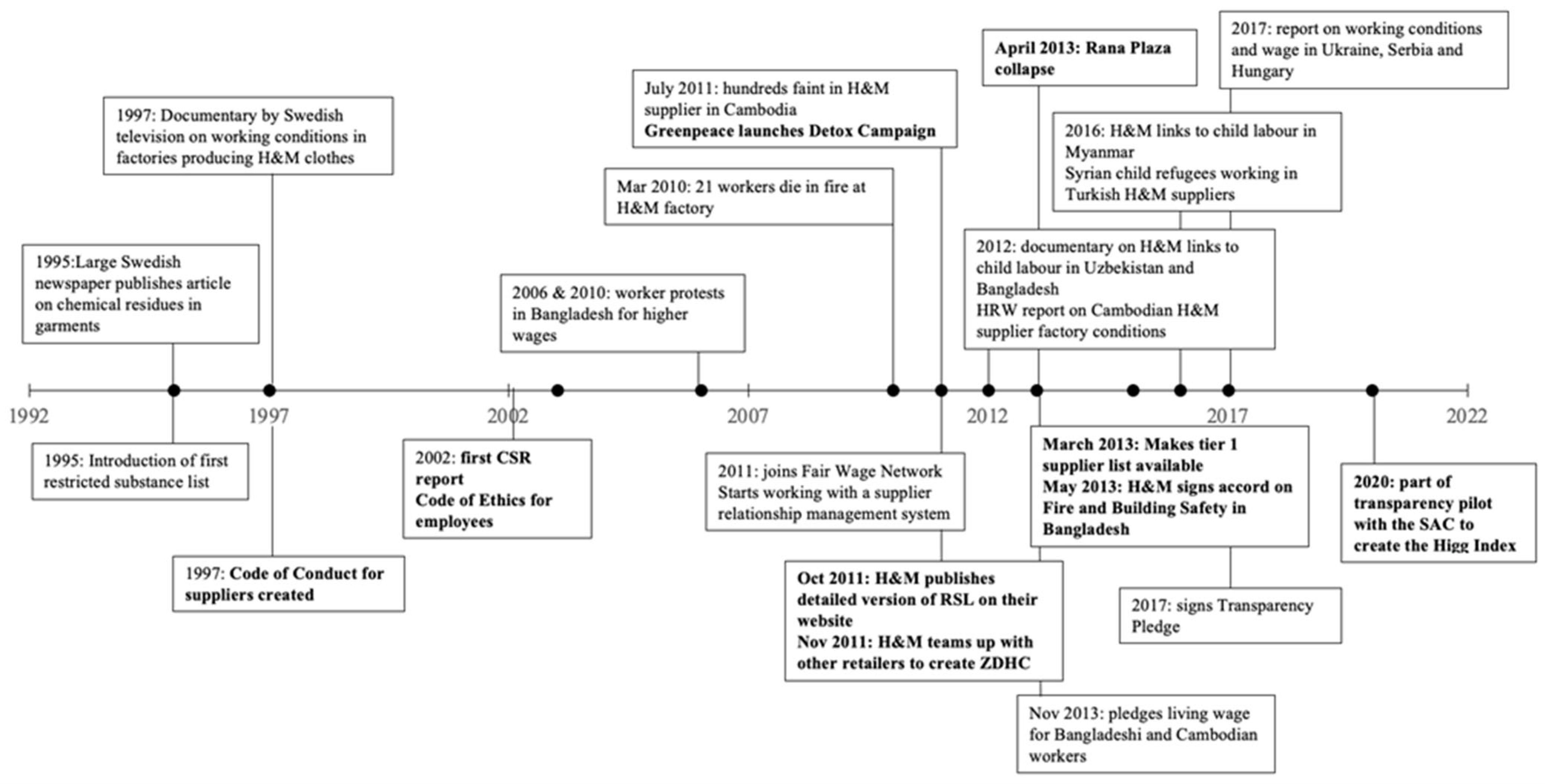

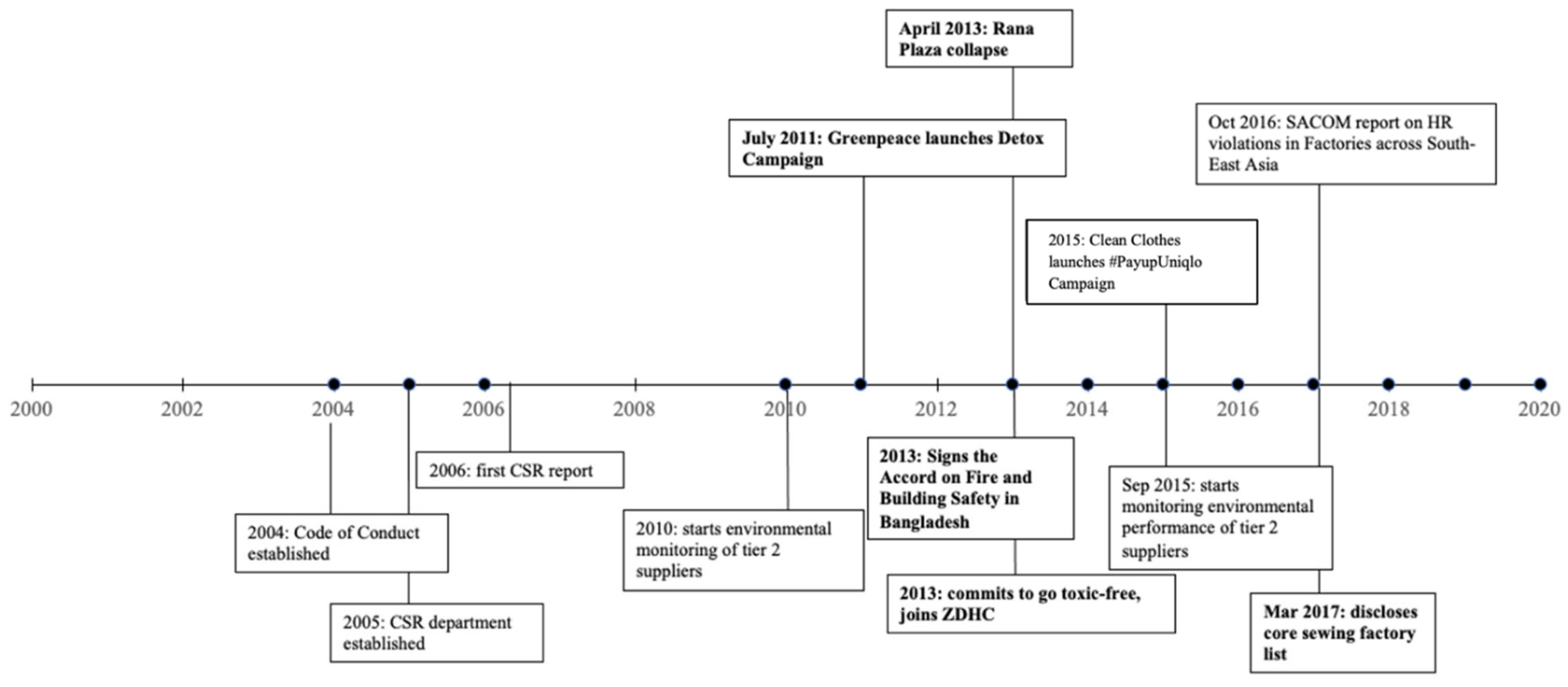

Appendix A. Company Scandal-CSR Timelines

Appendix B. Full Count Data for Retailer Scandals

| Retailer | Scandals |

| H&M | 1995: Large Swedish newspaper publishes article on chemical residues in garments, making wearers and people working in retail stores ill 1997: documentary by Swedish public television on working conditions 2006: Swedish radio broadcast program reveals deficient working conditions in jewelry industry in China (even though H&M not involved, is associated with it) 2006: worker protests, Bangladesh 2010: workers protest for higher wages in Bangladesh Mar 2010: 21 workers die in fire at H&M factory Jan 2010: tested samples of organic cotton show GMO traces 2010: H&M slashes unsold clothes outside NY store Jul 2011: hundreds faint in garment factory, Cambodia July 2011: Greenpeace Dirty Laundry report on water pollution in China (mostly targets H&M) July 2011: Launch of Greenpeace Detox Campaign 2012: German documentary reports H&M’s links to child labour and labour exploitation in Uzbekistan and Bangladesh 2012–2013: Human Rights Watch report on Cambodian factory conditions (some of which were H&M suppliers, although they were not the sole targets) April 2013: Rana Plaza collapse (not an H&M supplier, but H&M was associated with the scandal) Sep 2014: factory worker protests in Cambodia over living wages (H&M and Inditex) Aug 2016: H&M employed 14-year-old workers in Myanmar 2016: Report finds Syrian refugees are working in Turkish factory suppliers 2017: Report finds that viscose sourced causes extreme pollution Dec 2017: Ukraine, Serbia, and Hungary: Report by Clean Clothes Campaign details poverty wages and poor working conditions in garment factories producing for global brands (incl. Inditex and H&M) 2018: Report of abuses at large Indian supplier (H&M and Gap) July 2021: Report on wage-theft in garment supply chains (COVID-19) incriminating Inditex, H&M and Gap |

| TOTAL | 20 |

| Inditex | April 2005: Spectrum factory collapse, killing 60 workers Oct 2009: Found responsible for oil spill July 2011: Greenpeace Dirty Laundry report on water pollution in China (mostly targets H&M) July 2011: Launch of Greenpeace Detox Campaign August 2011: Illegal sweatshop slave labour scandal in Brazil Dec 2011: Clean Clothes campaign report about living conditions of textile workers in Tangier 20 Nov 2012: Report: Toxic Threads, the big Fashion Stitch-Up Greenpeace International investigates Zara (and other brands) for toxic chemicals in clothes 2012: factory fire Oct 2012: water pollution (?) April 2013: Rana Plaza collapse Oct 2013: Nine people killed in a fire that broke out in a garment factory close to Dhaka Sep 2014: Factory worker protests in Cambodia over living wages (H&M and Inditex) 2015: Inditex faces fines in Brazil over sweatshop scandal Dec 2016: Inditex found to have avoided paying millions of Euros in taxes between 2011 and 2014 2017: Report finds that viscose sourced causes extreme pollution Nov 2017: Nnotes sewn into Zara clothes saying workers are not getting paid Dec 2017: Ukraine, Serbia, and Hungary: Report by Clean Clothes Campaign details poverty wages and poor working conditions in garment factories producing for global brands (incl. Inditex and H&M) April 2021: Uyghur forced labour scandal (lawsuit filed against Inditex and Uniqlo) July 2021: Report on wage theft in garment supply chains (COVID-19) incriminating Inditex, H&M, and Gap |

| TOTAL | 17 |

| Gap Inc. | 1995: Labor conflict at Mandarin International factory in El Salvador (see Page 20) increases company’s awareness of factory conditions and the need to ensure vendor commitment to sourcing guidelines. 1999: Gap Inc. is one of many apparel retailers named in Saipan lawsuit 2000: Child labour allegations in outsourcing factories, Cambodia 2002: UNITE releases a study on working conditions in Gap factories 20S03: WWW (women working worldwide) published a research report entitled “bridging the gap” 2004: Oxfam released a report entitled “trading away our rights” Oct 2007: Child sweatshop shame July 2011: Greenpeace Dirty Laundry report on water pollution in China (mostly targets H&M) July 2011: Launch of Greenpeace Detox Campaign 2012–2013: Human Rights’ Watch report on worker conditions in Cambodian factories (use of FDCs) April 2013: Rana Plaza collapse April 2013: Toxic Threads investigation reveals how big brands like GAP Inc. are in business with polluting suppliers in Indonesia, leading to major water pollution Aug 2013: Aljazeera investigation reveals child labour in Old Navy factory in Bangladesh (Samies Finishing House factory) Jan 2014: Report released detailing worker abuses at Next Collections Limited factory in Bangladesh (producing Old Navy jeans) 2014: Earns the “Public Eye Jury Award” that aims to highlight the worse human rights violations and disregard for sustainability Aug 2014: Audit conducted for Gap reveals problems in two factories, Myanmar 2018: Report of abuses at large Indian supplier (H&M and Gap) June 2018: Report analyses gender-based violence in Asian Gap factories (H&M mentioned but not really targeted) July 2021: Report on wage theft in garment supply chains (COVID-19) incriminating Inditex, H&M, and Gap |

| TOTAL | 19 |

| Fast Retailing | July 2011: Greenpeace Dirty Laundry report on water pollution in China (mostly targets H&M) July 2011: Launch of Greenpeace Detox Campaign 2013: Rana Plaza 2015: Factory closure in Indonesia makes workers ask for severance pay, and start of Clean Clothes #payupUniqlo campaign Oct 2016: SACOM report on human rights violations in factories across South-East Asia April 2021: Uyghur forced labour scandal (lawsuit filed against Inditex and Uniqlo) |

| TOTAL | 5 |

Appendix C. Retailer Scandals and CSR sources

| H&M scandals | Audubon. (2010, 26 Jan). H&M Among Clothing Chains Caught in Organic Cotton Fraud Controversy. Retrieved from https://www.audubon.org/news/hm-among-clothing-chains-caught-organic-cotton-fraud-controversy (accessed on 1 August 2022) Clean Clothes Campaign. (2012, 25 Oct). H&M Under Fire as Swedish Television Unearths Cambodian Production Scandal. Retrieved from https://cleanclothes.org/news/2012/10/25/h-m-under-fire-as-swedish-television-unearths-cambodian-production-scandal (accessed on 1 August 2022) Dwyer, J. (2010, 06 Jan). A Clothing Clearance Where More Than Just the Prices Have Been Slashed. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/06/nyregion/06about.html (accessed on 1 August 2022) Facing Finance. (2012) [29]. H&M: Violations of Labor Rights in Uzbekistan, Bangladesh, and Cambodia. Retrieved from https://www.facing-finance.org/en/database/cases/violation-of-labour-rights-by-hm-in-uzbekistan-bangladesh-and-cambodia/ (accessed on 1 August 2022) Greenpeace (2011). Dirty Laundry: Unravelling the Corporate Connections to Toxix Water Pollution in China. Retrieved from https://www.greenpeace.org/static/planet4-international-stateless/2011/07/3da806cc-dirty-laundry-report.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2022) Greenpeace. (2018). Destination Zero: Seven years of detoxing the clothing industry. Retrieved from: https://www.greenpeace.org/static/planet4-international-stateless/2018/07/destination_zero_report_july_2018.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2022) Hendrisk, V. (2016, 02 Feb). Next and H&M address Syrian refugee children working in Turkish factories. Fashion United. Retrieved from https://fashionunited.uk/news/fashion/next-and-h-m-take-action-against-syrian-refugee-children-working-in-turkish-factories/2016020219256 (accessed on 1 August 2022) International Labour Organization (n.d.). The Rana Plaza Accident and its aftermath. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/geip/WCMS_614394/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 1 August 2022) Kaye, L. (2016, 24 Aug). H&M Embarrassed after 14-year-Olds Found Working in Burma Garment Factories. Triple Pundit. Retrieved from https://www.triplepundit.com/story/2016/hm-embarrassed-after-14-year-olds-found-working-burma-garment-factories/23301 (accessed on 1 August 2022) Kogg, B. (2009). Responsibility in the Supply Chain: Interorganizational Management of Environmental and Social Aspects in the Supply Chain—Case Studied from the Textile Sector. The International Institute for Industrial Environmental Economics. Retrieved from: https://lucris.lub.lu.se/ws/portalfiles/portal/4057664/1392617.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2022) Kourabas, M. (2014, 26 Sep). In Wake of New Protests, H&M and Others Commit to Living Wages in Cambodia. Triple Pundit. Retrieved from https://www.triplepundit.com/story/2014/wake-new-protests-hm-and-others-commit-living-wages-cambodia/40531 (accessed on 1 August 2022) Radio Free Asia. (2011, 25 Aug). Cambodia: Hundreds faint in garment factory. Retrieved from https://www.refworld.org/docid/4e6e02ad1a.html (accessed on 1 August 2022) Tumber, H., & Waisbord, S. (Eds.). (2019). The routledge companion to media and scandal. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351173001 (accessed on 1 August 2022) |

| H&M CSR | Lee, J. (2015, 05 Feb). H&M CEO: Reducing Consumption Isn’t the Answer. Triple-Pundit. Retrieved from: https://www.triplepundit.com/story/2015/hm-ceo-reducing-consumption-isnt-answer/58056 (accessed on 1 August 2022) H&M. (2002–2020). Sustainability Reporting. Retrieved from: https://hmgroup.com/sustainability/sustainability-reporting/ (accessed on 1 August 2022) |

| Inditex Scandals | Butler, S. (2015, 12 May). Zara owner Inditex faces fines in Brazil over poor working conditions claim. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2015/may/12/zara-owner-inditex-fines-brazil-working-conditions-claim (accessed on 1 August 2022) Clean Clothes Campaign. (2017) [20]. Europe Floor Wage. Retrieved from https://cleanclothes.org/campaigns/europe-floor-wage (accessed on 1 August 2022) Díaz, N., García-Ochoa, C., Karimova, H., Garro, R. (2012). Inditex: A Closer View of the Company. Ricardo Garro Ruiz. Retrieved from: https://www.eoi.es/blogs/ricardogarro/2012/02/02/inditex-a-closer-view-of-the-company/ (accessed on 1 August 2022) IndustriAll. (2014). Special Report: Inditex and IndustriALL Global Union: Getting results from a global framework agreement. Retrieved from: http://www.industriall-union.org/special-report-inditex-and-industriall-global-union-getting-results-from-a-global-framework (accessed on 1 August 2022) Kaye, L. (2017, 09 Nov). Workers Sew Nightmare Into Zara’s Supply Chain. Triple Pundit. https://www.triplepundit.com/story/2017/workers-sew-nightmare-zaras-supply-chain/14481 (accessed on) Kaye, L. (2017, 14 Nov). Zara Promises to Set Up Fund for Unpaid Turkish Workers. Triple Pundit. Retrieved from https://www.triplepundit.com/story/2017/zara-promises-set-fund-unpaid-turkish-workers/14416 (accessed on 1 August 2022) Kourabas, M. (2014, 26 Sep). In Wake of New Protests, H&M and Others Commit to Living Wages in Cambodia. Triple Pundit. Retrieved from https://www.triplepundit.com/story/2014/wake-new-protests-hm-and-others-commit-living-wages-cambodia/40531 (accessed on 1 August 2022) Oxfam. (2016, 08 Dec). Zara Scandal shows tax dodging still in fashion, says Oxfam. Retrieved from https://www.oxfam.org/fr/node/9092 (accessed on 1 August 2022) Perez, M. (2014, 20 Jan). The Social (Ir)Responsibility of Inditex. United Explanations. Retrieved from http://unitedexplanations.org/english/2014/01/20/the-social-irresponsibility-of-inditex-2/ (accessed on 1 August 2022) |

| Inditex CSR | Inditex. (2002–2020). Annual Reports. Retrieved from https://www.inditex.com/investors/investor-relations/annual-reports (accessed on 1 August 2022) |

| Gap Scandals | Bain, M. (2018, 25 Jun). H&M, Columbia, and others are accused of ignoring disturbing abuses at a large Indian supplier. Quartz. Retrieved from https://qz.com/1313585/hm-gap-abercrombie-and-others-are-accused-of-ignoring-disturbing-abuses-at-a-large-indian-supplier/ (accessed on 1 August 2022) Campbell, F. (Producer), & Kenyon. P., (Reporter). (2000). Gap and Nike: No Sweat? [Documentary]. BBC News. Fault Lines. (2013, 26 Aug). Made in Bangladesh. [Documentary]. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/program/fault-lines/2013/8/26/made-in-bangladesh (accessed on 1 August 2022) Global Labour Justice. (2018, May). Gender Based Violence in the GAP Garment Supply Chain. Retrieved from: https://globallaborjustice.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/GBV-Gap-May-2018.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2022) Hodal, K. (2018, 05 Jun). Abuse is daily reality for female garment workers for Gap and H&M, says report. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2018/jun/05/female-garment-workers-gap-hm-south-asia (accessed on 1 August 2022) Human Rights Watch (2015, March 11). Work Faster or Get Out. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/03/11/work-faster-or-get-out/labor-rights-abuses-cambodias-garment-industry (accessed on 1 August 2022) Institute for Global Labour and Human Rights. (2014, 13 Jan). Gap and Old Navy in Bangladesh. Retrieved from https://issuu.com/iglhr/docs/1310-iglhr-gapoldnavyinbangladesh/9 (accessed on 1 August 2022) Read, J. E. (2013, 19 April). Polluting Paradise: Gap, Inc Among Companies Exposed in Indonesian Toxic Water Scandal. Sustainable Brands. Retrieved from https://sustainablebrands.com/read/supply-chain/polluting-paradise-gap-inc-among-companies-exposed-in-indonesian-toxic-water-scandal (accessed on 1 August 2022) Scheidns, J. (2004, 12 May). World: Gap Reports Labor Violations at Factories. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.corpwatch.org/article/world-gap-reports-labor-violations-factories (accessed on 1 August 2022) Teather, D. (2004, 13 May). Gap admits to child labour violations in outsource factories. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/business/2004/may/13/7 (accessed on 1 August 2022) |

| Gap CSR | Gap Inc. (2003–2020). Social Responsibility Report. Retrieved from https://www.gapinc.com/en-us/values/sustainability/esg-hub (accessed on 1 August 2022) |

| Fast Retailing scandals | Boykoff, P. (2015, 15 Jan). Uniqlo Owner Promises to Clean up its Factories. CNN. Retrieved from: https://money.cnn.com/2015/01/15/news/fast-retailing-uniqlo-labor-violations/index.html (accessed on 1 August 2022) Clean Clothes Campaign. (2015). Jaba Garmindo. Retrieved from: https://cleanclothes.org/campaigns/jaba-garmindo (accessed on 1 August 2022) Kuo, L. (2015, 15 Jan). Uniqlo promises to improve life for workers at its factories in China. Quartz. Retrieved from: https://qz.com/327131/uniqlo-promises-to-improve-life-for-workers-at-its-factories-in-china/ (accessed on 1 August 2022) McKevitt, J. (2017, March 8). Uniqlo strives for higher sustainability model after controversy. Supply Chain Dive. Retrieved from https://www.supplychaindive.com/news/uniqlo-ethical-sourcing-sustainability-report/437601/ (accessed on 1 August 2022) War on Want (2015, 23 Feb). The reality behind UNIQLO’s corporate social responsibility promises. Retrieved from: https://waronwant.org/news-analysis/reality-behind-uniqlos-corporate-social-responsibility-promises (accessed on 1 August 2022) |

| Fast Retailing CSR | Fast Retailing. (2006–2020). Sustainability Report. Retrieved from https://www.fastretailing.com/eng/sustainability/report/past.html (accessed on 1 August 2022) |

References

- Boström, M.; Micheletti, M. Introducing the Sustainability Challenge of Textiles and Clothing. J. Consum. Policy 2016, 39, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asia Floor Wage Alliance. Money Heist: COVID-19 Wage Theft in Global Garment Supply Chains. 2021. Available online: https://asia.floorwage.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Money-Heist_Book_Final-compressed.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Paton, E.; Gallois, L.; Breeden, A. Fashion Retailers Face Inquiry Over Suspected Ties to Forced Labor in China. The New York Times. 2 July 2021. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/02/fashion/xinjiang-forced-labor-Zara-Uniqlo-Sketchers.html (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Bick, R.; Halsey, E.; Ekenga, C.C. The global environmental injustice of fast fashion. Environ. Health 2018, 17, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhardwaj, V.; Fairhurst, A. Fast fashion: Response to changes in the fashion industry. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2010, 20, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattab, T.A.; Abdelrahman, M.S.; Rehan, M. Textile dyeing industry: Environmental impacts and remediation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2020, 27, 3803–3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. The green, blue and grey water footprint of crops and derived crop products. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 15, 1577–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhav, S.; Ahamad, A.; Singh, P.; Mishra, P.K. A review of textile industry: Wet processing, environmental impacts, and effluent treatment methods. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2018, 27, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimkar, U. Sustainable chemistry: A solution to the textile industry in a developing world. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2018, 9, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirvanimoghaddam, K.; Motamed, B.; Ramakrishna, S.; Naebe, M. Death by waste: Fashion and textile circular economy case. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 718, 137317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esbenshade, J. Monitoring Sweatshops; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2004; Available online: http://muse.jhu.edu/book/9762 (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Dauvergne, P. The Shadows of Consumption: Consequences for the Global Environment; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; Available online: http://go.utlib.ca/cat/6642327 (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Gereffi, G. Global value chains in a post-Washington Consensus world. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 2014, 21, 9–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebaron, G.; Lister, J. Benchmarking global supply chains: The power of the ‘ethical audit’ regime. Rev. Int. Stud. 2015, 41, 905–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Büthe, T.; Mattli, W. The New Global Rulers: The Privatization of Regulation in the World Economy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gereffi, G. Global Value Chains and Development: Redefining the Contours of 21st Century Capitalism; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J. Rethinking Private Authority: Agents and Entrepreneurs in Global Environmental Governance; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- van der Ven, H. Beyond Greenwash? Explaining Credibility in Transnational Eco-Labeling; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- van der Ven, H.; Sun, Y.; Cashore, B. Sustainable Commodity Governance and the Global South. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 186, 107062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, E. Global Sourcing in Fast Fashion Retailers: Sourcing Locations and Sustainability Considerations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.; What Are Fast Fashion Brands Doing to Tackle Fashion’s Sustainability Problem? [News Item]. Vogue. Available online: https://www.vogue.com.au/fashion/news/what-are-fast-fashion-brands-doing-to-tackle-fashions-sustainability-problem/image-gallery/00db9acbbb9cb5da053486ae2f3dc59b (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Lyon, T.P.; Montgomery, A.W. The Means and End of Greenwash. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Mason, M. Transparency in Global Environmental Governance: Critical Perspectives; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7ztf0q (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Schleifer, P.; Fiorini, M.; Auld, G. Transparency in transnational governance: The determinants of information disclosure of voluntary sustainability programs. Regul. Gov. 2019, 13, 488–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Walter, G.; Van de Graaf, T.; Andrews, N. Energy Governance, Transnational Rules, and the Resource Curse: Exploring the Effectiveness of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). World Dev. 2016, 83, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clean Clothes Campaign. Follow the Thread. The Need for Supply Chain Transparency in the Garment and Footwear Industry. 20 April 2017. Available online: https://cleanclothes.org/file-repository/resources-publications-follow-the-thread-the-need-for-supply-chain-transparency-in-the-garment-and-footwear-industry/view (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Carbon Disclosure Project. Why Disclose a Company? Available online: https://www.cdp.net/en/companies-discloser (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Fashion Revolution. Transparency Is Trending. 2019. Available online: https://www.fashionrevolution.org/transparency-is-trending/ (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Human Rights Watch. Work Faster or Get Out. 11 March 2015. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/03/11/work-faster-or-get-out/labor-rights-abuses-cambodias-garment-industry (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Eberlein, B.; Abbott, K.W.; Black, J.; Meidinger, E.; Wood, S. Transnational business governance interactions: Conceptualization and framework for analysis. Regul. Gov. 2014, 8, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Ven, H. Correlates of rigorous and credible transnational governance: A cross-sectoral analysis of best practice compliance in eco-labeling. Regul. Gov. 2015, 9, 276–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniato, F.; Caridi, M.; Crippa, L.; Moretto, A. Environmental sustainability in fashion supply chains: An exploratory case based research. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 135, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Han, H.; Lee, P.K.C. An Exploratory Study of the Mechanism of Sustainable Value Creation in the Luxury Fashion Industry. Sustainability 2017, 9, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Islam, M.A.; Deegan, C. Media pressures and corporate disclosures of social responsibility performance information: A study of two global clothing and sports retail companies. Account. Bus. Res. 2010, 40, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auke, E.; Simaens, A. Corporate responsibility in the fast fashion industry: How media pressure affected corporate disclosure following the collapse of Rana Plaza. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. Manag. 2019, 23, 356–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graafland, J.J. Sourcing ethics in the textile sector: The case of C&A. Bus. Ethics: A Eur. Rev. 2002, 11, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, X.; Shi, D.; Li, X. Governance of sustainable supply chains in the fast fashion industry. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, R.M.; Qin, F.; Brause, A. Does Monitoring Improve Labor Standards? Lessons from Nike. ILR Rev. 2007, 61, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrikopoulos, A.; Kriklani, N. Environmental Disclosure and Financial Characteristics of the Firm: The Case of Denmark. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2013, 20, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Pavelin, S. Voluntary Environmental Disclosures by Large UK Companies. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2006, 33, 1168–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartley, T.; Child, C. Shaming the Corporation: The Social Production of Targets and the Anti-Sweatshop Movement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2014, 79, 653–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guckian, M.L.; Chapman, D.A.; Lickel, B.; Markowitz, E.M. “A few bad apples” or “rotten to the core”: Perceptions of corporate culture drive brand engagement after corporate scandal. J. Consum. Behav. 2018, 17, e29–e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabel, C.; Fung, A.; O’Rourke, D. Realizing Labor Standards. In Can We Put an End to Sweatshops? Beacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kuipers, J. Corporate Values and Scandals in the Fashion Industry; University of Twente: Enschede, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kuperman, A. Sustainabiliy in the Fashion Supply Chain in a Fast Fashion Era: An Exploratory Multiple Case Study Research; University of Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Beard, N.D. The Branding of Ethical Fashion and the Consumer: A Luxury Niche or Mass-market Reality? Fash. Theory 2008, 12, 447–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, I.; Sadorsky, P. The Relationship between Environmental Commitment and Managerial Perceptions of Stakeholder Importance. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Ven, H. Socializing the C-suite: Why Some Big-Box Retailers are “Greener” than Others. Bus. Politics 2014, 16, 31–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transparency International Sverige. Transparens i företagens rapportering: En studie av de 20 största företagen i Sverige; Transparency International Sverige: Stockholm, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Seawright, J.; Gerring, J. Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative Options. Political Res. Q. 2008, 61, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, A. Apparel Brands Report, 2021. Fashion Retail, 31 December 2021. Available online: https://fashionretail.blog/2021/12/13/apparel-brands-report-2021/ (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Forbes. H&M—Hennes & Mauritz. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/companies/hm-hennes-mauritz/ (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Parietti, M. H&M vs. Zara vs. Uniqlo: What’s the Difference? Investopedia. 2021. Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/articles/markets/120215/hm-vs-zara-vs-uniqlo-comparing-business-models.asp (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- COS. Sustainability. Available online: http://www.cosstores.com/en/sustainability.html (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Kaye, L.; Workers Sew a Nightmare into Zara’s Supply Chain. Triple Pundit. 2017. Available online: https://www.triplepundit.com/story/2017/workers-sew-nightmare-zaras-supply-chain/14481 (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Fast Retailing. About Us: History (1949–2003). Available online: https://www.fastretailing.com/eng/about/history/ (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Fast Retailing. About Us: History (2005). Available online: https://www.fastretailing.com/eng/about/history/2005.html (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Fashion Revolution. About. Fashion Revolution. Available online: https://www.fashionrevolution.org/about/ (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Buckley, T.R. Gap and Benetton Once Ruled Fashion—And Their Success Ultimately Led to Their Demise. Fast Company, 24 September 2021. Available online: https://www.fastcompany.com/90678948/gap-and-benetton-once-ruled-fashion-and-their-success-ultimately-led-to-their-demise (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Fashion Revolution. Fashion Transparency Index 2020. 2020. Available online: https://issuu.com/fashionrevolution/docs/fr_fashiontransparencyindex2020/1 (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Facing Finance. H&M: Violations of Labor Rights in Uzbekistan, Bangladesh, and Cambodia. 2012. Available online: https://www.facing-finance.org/en/database/cases/violation-of-labour-rights-by-hm-in-uzbekistan-bangladesh-and-cambodia/ (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Paton, E. After Factory Disaster, Bangladesh Made Big Safety Strides. Are the Bad Days Coming Back? The New York Times. 1 March 2020. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/01/world/asia/rana-plaza-bangladesh-garment-industry.html (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Grafström, M.; Windell, K.; Adamsson, E. Normerande Bilder av Ansvar—En Studie av hur fem BörsföRetag Framställs i Svenska Medier, 1995–2012. Stockholm Centre for Organizational Research, 2015. Available online: http://su.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:814635/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Tumber, H.; Waisbord, S. (Eds.) The Routledge Companion to Media and Scandal; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reputation Management. Interview with H&M CEO Karl-Johan Persson. Available online: https://www.reputation-inc.com/our-thinking/hm-ceo-karl-johan-persson-in-the-future-consumers-should-have-access-to-the-total-sustainability-information-of-a-product (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- H&M Group. Store Count per Brand. Available online: https://hmgroup-prd-app.azurewebsites.net/about-us/markets-and-expansion/store-count-per-brand/ (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- The Business of Fashion. Karl-Johan Persson is part of the BoF 500. Available online: https://www.businessoffashion.com/community/people/karl-johan-persson (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Hoikkala, H. H&M CEO Sees “Terrible” Fallout as Consumer Shaming Spreads—BNN Bloomberg. BNN Bloomberg, 27 October 2019. Available online: https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/h-m-ceo-sees-terrible-fallout-as-consumer-shaming-spreads-1.1338212 (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Lee, J.; H&M CEO: Reducing Consumption Isn’t the Answer. 3BLmedia. 2015. Available online: https://www.3blmedia.com/News/HM-CEO-Reducing-Consumption-Isnt-Answer (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- De Wée, T. OPINION: An Open Letter to Karl-Johan Persson, CEO of H&M. Fashion Revolution, 7 November 2019. Available online: https://www.fashionrevolution.org/opinion-an-open-letter-to-karl-johan-persson-ceo-of-hm/ (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Know The Chain. Five Years of the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act. 2015. Available online: https://knowthechain.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/KnowTheChain_InsightsBrief_093015.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Gap Inc. Athleta. Available online: https://gapinc.com/en-us/about/athleta (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Aman, H.; Beeks, W.; Brown, P.R. Corporate Governance and Transparency in Japan. SSRN 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.; Hashimoto, S.; Grow, H. Japan—Keeping it complicated. In CG Watch 2018. Hard Decisions. Asia Faces Tough Choices in CG Reform; Yonts, C., Allen, J., Zhou, M., Eds.; Asian Corporate Governance Association and CLSA Limited: Hong Kong, China, 2018; pp. 207–239. Available online: https://www.acga-asia.org/cgwatch-detail.php?id=362 (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Inajima, T.; Reynolds, I. Japan to Lay Out Human Rights Guidelines for Companies by Summer. Bloomberg, 15 February 2022. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-02-15/japan-to-lay-out-human-rights-guidelines-for-companies-by-summer#:~:text=The%20%E2%80%9Cdue%20diligence%E2%80%9D%20guidelines%20are,its%20own%20law%2C%20Hagiuda%20said (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Porter, M.; Kramer, M. Strategy and Society: The Link Between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Willard, B. The Sustainability Advantage: Seven Business Case Benefits of a Triple Bottom Line; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Potoski, M.; Prakash, A. Green Clubs and Voluntary Governance: ISO 14001 and Firms’ Regulatory Compliance. Am. J. Political Sci. 2005, 49, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potoski, M.; Prakash, A. (Eds.) Voluntary Programs: A Club Theory Perspective; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; Available online: http://link.library.utoronto.ca/MyUTL/goto_catalogue_url.cfm?where=ckey&what=8848565 (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- van der Ven, H.; Bernstein, S.; Hoffmann, M. Valuing the Contributions of Non-State and Subnational Actors to Climate Governance. Glob. Environ. Politics 2017, 17, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenpeace. Self Regulation: A Fashion Fairytale? Part 2. 2021. Available online: https://www.greenpeace.de/publikationen/20211122-greenpeace-detox-fashion-fairytale-engl-pt2_0.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Andonova, L.B.; Hale, T.N.; Roger, C.B. National Policy and Transnational Governance of Climate Change: Substitutes or Complements? Int. Stud. Q. 2017, 61, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashore, B.; Knudsen, J.S.; Moon, J.; van der Ven, H. Private authority and public policy interactions in global context: Governance spheres for problem solving. Regul. Gov. 2021, 15, 1166–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, J.S.; Moon, J. Visible Hands: Government Regulation and International Business Responsibility; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tzankova, Z. Can private governance boost public policy? Insights from public–private governance interactions in the fisheries and electricity sectors. Regul. Governance 2020, 15, 1248–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fashion Revolution. Fashion Transparency Index 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.fashionrevolution.org/about/transparency/ (accessed on 1 August 2022).

| Hypotheses | Measurement |

|---|---|

| H1: Retailers with higher revenues will have higher levels of transparency | Sales and revenue information, retrieved from Forbes company profiles (Forbes) |

| H2: Retailers that have faced ethical or environmental scandals will have higher levels of transparency | 1. Count data of scandals created by searching for “scandal” or “controversy” and each retailer’s name in: Clean Clothes’ Campaign archive, Triple-Pundit, New York Times, Bloomberg, Financial Times, and Google Search. 2. Process tracing the evolution of CSR initiatives to find direct relationships with scandals. CSR initiatives were collected through the same databases as the scandals, and through retailers’ CSR reports and brand websites. A scandal is defined as an event which has transgressed sustainability or ethical values, and which has been disclosed by a third party (usually an NGO or news media outlet). |

| H3: Retailers that put transparency at the core of their brand image and communication with consumers will have higher levels of transparency | 1. Count data of mentions of transparency in CSR reports, collected by searching for the term “transparen”. 2. Searching for the presence of niche brands focused on sustainability, transparency, or traceability. |

| H4: Retailers whose senior executives have been socialized through interactions with sustainability stakeholders will have higher levels of transparency | 1. Count data of MSSN (multi-stakeholder sustainability network) partnerships, collected through retailer “partnerships” or “collaborations” pages. 2. Qualitative investigation into CEO socialization and value changes, through interviews with past or current CEOs and chairmen and Forbes profiles (Forbes). |

| H5: Retailers headquartered in countries that have more stringent laws and cultural expectations concerning transparency will have higher levels of transparency | 1. Searching for country or regional laws addressing disclosure or due diligence. 2. Measure of countries’ transparency expectancy through the RTI (Right to Information) rating. |

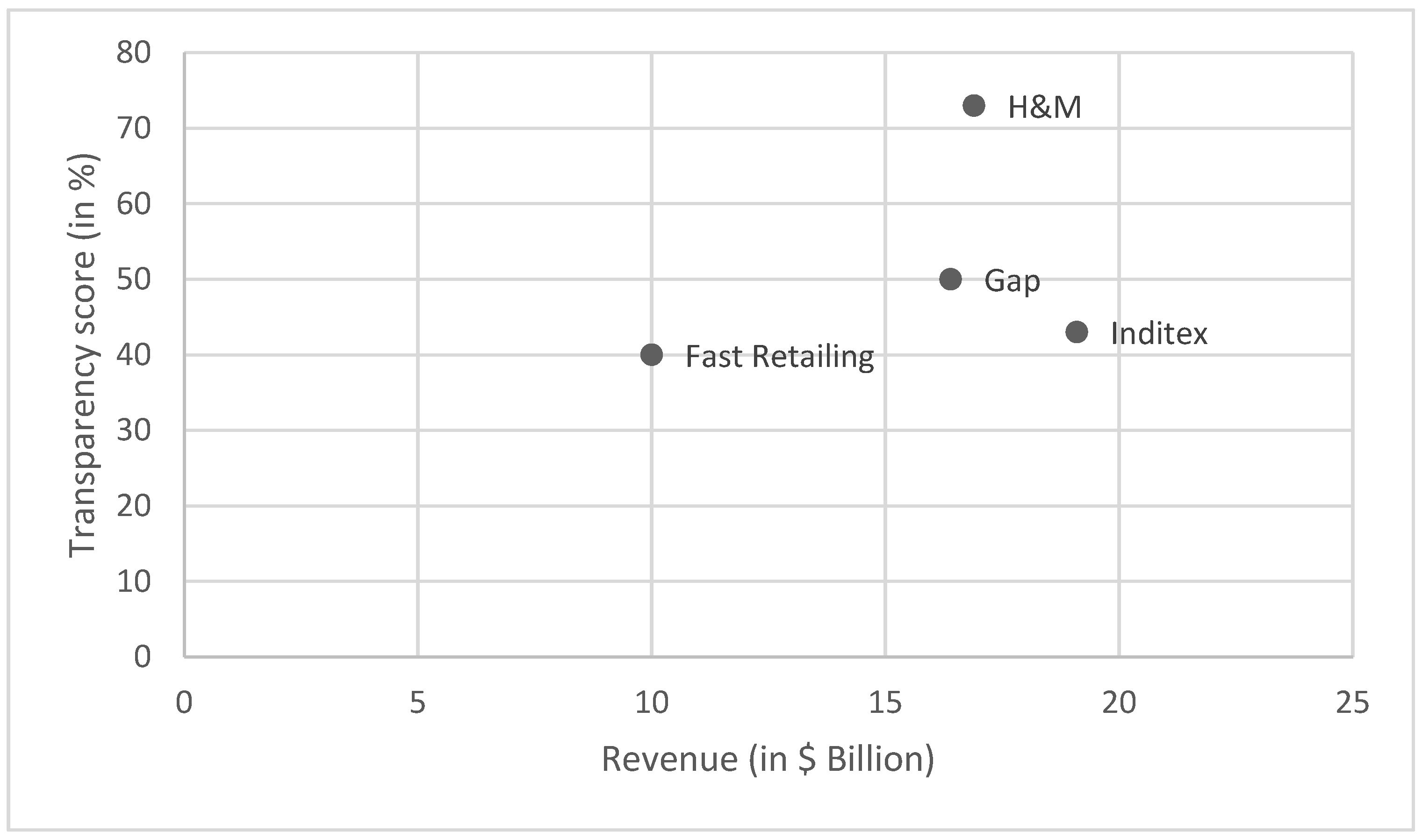

| Retailer | H&M | Inditex | Gap | Fast Retailing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transparency Score 2019 | 61% | 46% | 54% | 38% |

| Transparency Score 2020 | 73% | 43% | 50% | 40% |

| Retailer | H&M | Inditex | Gap | Fast Retailing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue 2020 ($B) | 16.9 | 19.1 | 16.4 | 10 |

| Sales | 19.1 | 23.4 | 13.8 | 18.9 |

| Transparency Score 2020 | 73% | 43% | 50% | 40% |

| Retailer | H&M | Inditex | Gap | Fast Retailing |

| Number of scandals | 20 | 17 | 19 | 5 |

| FTI 2020 | 73% | 43% | 50% | 40% |

| H&M | Inditex | Gap | Fast Retailing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of scandals (1995–2010) | 8 | 2 | 7 | 0 |

| Year | H&M | Inditex | Gap | Fast Retailing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | Chemical residues found in garments. Introduction of first restricted substance list. | Labour conflict at a factory in El Salvador. | ||

| 1996 | Code of Vendor Conduct created. | |||

| 1997 | Documentary on working conditions in suppliers. Code of Conduct for suppliers created. | |||

| 1999 | Gap named in Saipan lawsuits (sweatshops). | |||

| 2000 | Internal guidelines of conduct created. | Child labour allegations. | ||

| 2001 | Code of Conduct created. | Guidelines to protect foreign workers implemented. | ||

| 2002 | First CSR report. Code of ethics for employees. | First CSR report. | Study on working conditions in Gap factories. | |

| 2003 | First CSR report. | |||

| 2004 | Report finds human rights abuse in supply chains. Gap and other retailers found guilty in Saipan lawsuit. | Code of Conduct create. | ||

| 2005 | Supplier factory collapses, 60 workers die. | CSR department created. | ||

| 2006 | Internal guidelines for responsible practices adopted. | First CSR report. | ||

| 2010 | Workers protest in Bangladesh for higher wages. March: 21 workers die in fire at H&M factory. | Starts environmental monitoring of T2 suppliers. | ||

| 2011 | July: Greenpeace Detox Campaign. Oct: publishes detailed version of RSL on their website. Nov: teams up with other retailers to create Zero Discharge of Hazardous Chemicals (ZDHC). Nov: Joins Sustainable Apparel Coalition (SAC). | July: Greenpeace Detox Campaign. Aug: Slave labour/sweatshops in Brazil. Dec: report on living conditions of textile workers in Tangier. Nov: joins SAC. | July: Greenpeace Detox Campaign. | July: Greenpeace Detox Campaign. |

| 2012 | Links to child labour in Uzbekistan and Bangladesh. | Updates CoC to require publishing supplier list. Nov 2012: commits to go toxic-free, joins ZDHC. | Commits to go toxic-free, joins ZDHC. Nov: joins SAC. | |

| 2013 | March: publishes T1 supplier list. April: Rana Plaza collapse. May: Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh. Nov: pledges living wage for Bangladeshi and Cambodian workers. | April: Rana Plaza collapse. May: Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh. May: Pledges to publish supplier list. | April: Rana Plaza collapse. May 2013: joins Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety. Aug: Aljazeera investigation reveals child labour in factory in Bangladesh. | April: Rana Plaza collapse. May: Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh. |

| 2014 | Publishes T2 supplier list. | Admits to child labour violations in CSR report. | ||

| 2015 | Clean Clothes launches #PayupUniqlo Campaign. Sep: starts monitoring environmental performance of T2 suppliers. | |||

| 2016 | Links to child labour in Myanmar. Syrian child refugees working in Turkish H&M suppliers. | Publishes T2 supplier list. | Publishes T1 suppliers. | SACOM report on HR violations in Factories across South-East Asia. Joins the SAC and Higg index project. |

| 2017 | Report on working conditions and wages in Ukraine, Serbia and Hungary. Signs Transparency Pledge. | Report on working conditions and wages in Ukraine, Serbia and Hungary. | Starts monitoring social and environmental performance of T2 suppliers. | March: discloses core sewing factory list. |

| Report Years | H&M | Inditex | Gap | Fast Retailing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 1 (0.01) * | 16 (0.09) | X | X |

| 2003 | 2 (0.03) | 0 | 14 (0.3) | X |

| 2004 | 3 (0.04) | 18 (0.33) | 12 (0.19) | X |

| 2005 | 4 (0.05) | 1 (0.01) | 10 (0.11) | X |

| 2006 | 0 | 43 (0.1) | 10 (0.11) | X |

| 2007 | 0 | 35 (0.08) | 13 (0.08) | 2 (0.07) |

| 2008 | 14 (0.11) | 38 (0.1) | 13 (0.08) | 1 (0.03) |

| 2009 | 21 (0.13) | 33 (0.1) | 15 (0.09) | 0 |

| 2010 | 20 (0.12) | 34 (0.11) | 15 (0.09) | 3 (0.15) |

| 2011 | 8 (0.09) | 35 (0.12) | 24 (0.17) | 4 (0.18) |

| 2012 | 2 (0.28) | 29 (0.09) | 24 (0.17) | 6 (0.26) |

| 2013 | 21 (0.23) | 22 (0.07) | 5 (0.04) | 6 (0.26) |

| 2014 | 29 (0.25) | 27 (0.08) | 5 (0.04) | 9 (0.39) |

| 2015 | 26 (0.2) | 36 (0.11) | 13 (0.12) | 6 (0.26) |

| 2016 | 63 (0.51) | 46 (0.13) | 13 (0.12) | 5 (0.17) |

| 2017 (first year of FTI) | 51 (0.5) | 76 (0.2) | 7 (0.11) | 6 (0.12) |

| 2018 | 73 (0.67) | 72 (0.17) | 10 (0.15) | 1 (0.05) |

| 2019 | 40 (0.47) | 92 (0.19) | 12 (0.15) | 1 (0.04) |

| 2020 | 117 (1.39) | 82 (0.14) | 3 (0.06) | 1 (0.06) |

| Brand and MSSN | H&M | Inditex | Gap | Fast Retailing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACT (with IndustriALL Global Union) | X | X | ||

| Better Cotton Initiative (BCI) | X | X | X | X |

| Better Work Programme (ILO) | X | X | X | X |

| CanopyStyle | X | X | X | |

| CEO Water Mandate (UN Global Compact) | X | X | X | |

| Ellen Mac Arthur Foundation | X | X | X | |

| ETI (Ethical Trading Initiative) | X | X | ||

| Fair Labour Association (FLA) | X | |||

| The Fashion Pact | X | X | X | |

| FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) | X | |||

| Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh | X | X | X | |

| SAC (Sustainable Apparel Inditex) Higg index | X | X | X | X |

| ZDHC MRSL | X | X | X | X |

| Textile Exchange | X | X | X | X |

| TFCD (Task force on Climate related Financial Disclosures risk assessment) | X | X | ||

| WWF | X | X | ||

| TOTAL | 14 | 15 | 9 | 7 |

| Retailer | H&M | Inditex | Gap | Fast Retailing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Sweden | Spain | USA | Japan |

| RTI rating | 101 | 73 | 83 | 76 |

| Transparency Index 2020 | 73% | 43% | 50% | 40% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fraser, E.; van der Ven, H. Increasing Transparency in Global Supply Chains: The Case of the Fast Fashion Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11520. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811520

Fraser E, van der Ven H. Increasing Transparency in Global Supply Chains: The Case of the Fast Fashion Industry. Sustainability. 2022; 14(18):11520. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811520

Chicago/Turabian StyleFraser, Eve, and Hamish van der Ven. 2022. "Increasing Transparency in Global Supply Chains: The Case of the Fast Fashion Industry" Sustainability 14, no. 18: 11520. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811520