Building Health and Wellness Service Experience Extension: A Case Study of Bangkok, Thailand

Abstract

:1. Introduction

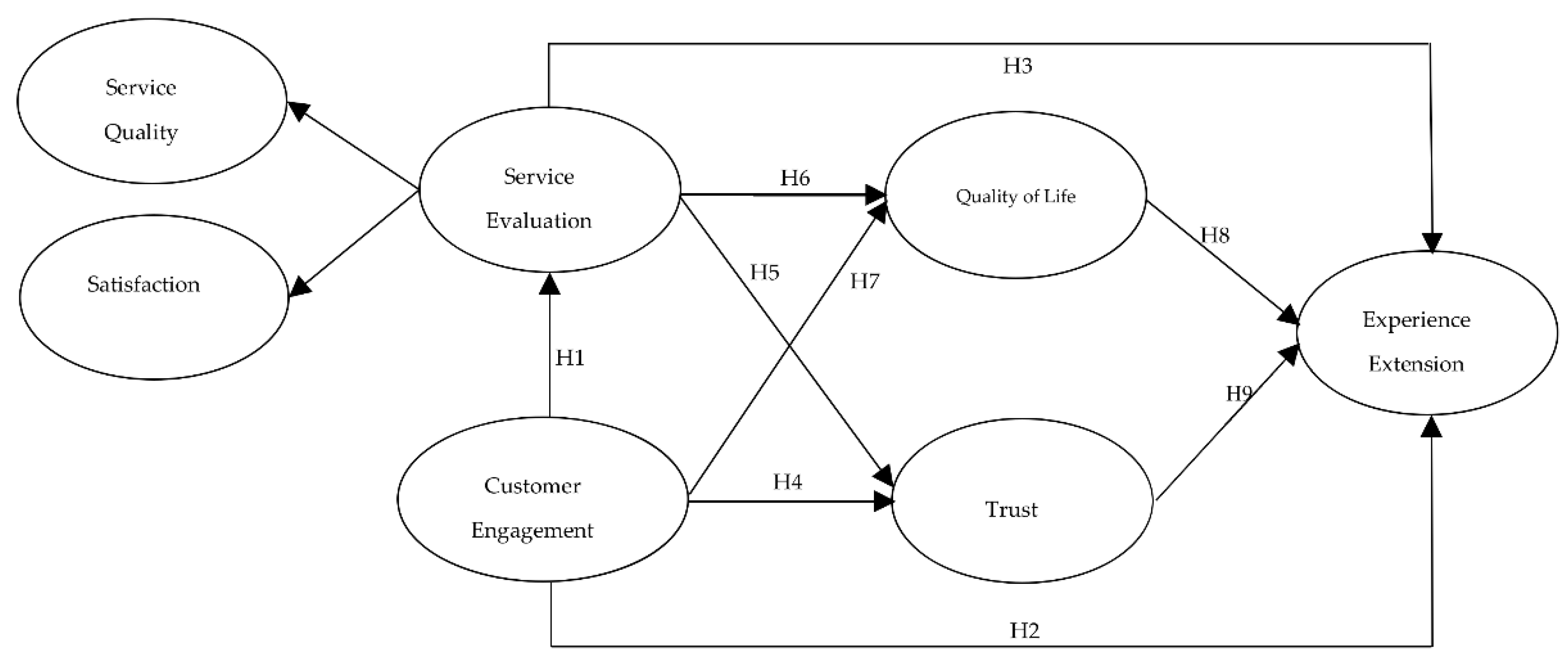

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Health and Wellness Service Evaluation

2.2. Customer Engagement

2.3. Trust in the Health and Wellness Service

2.4. Quality of Life

2.5. Experience Extension

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Setting

3.2. Measures

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Profile of Respondents

4.2. Common Method Bias

4.3. Measurement Assessment

4.4. Structural Model and Hypotheses Tests

4.5. Additional Analysis

5. Conclusions and Discussion

6. Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

7. Limitations and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mak, A.H.; Wong, K.K.; Chang, R.C. Health or self-indulgence? The motivations and characteristics of spa-goers. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 11, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghavvemi, S.; Ormond, M.; Musa, G.; Isa, C.R.M.; Thirumoorthi, T.; Mustapha, M.Z.B.; Chandy, J.J.C. Connecting with prospective medical tourists online: A cross-sectional analysis of private hospital websites promoting medical tourism in India, Malaysia and Thailand. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beladi, H.; Chao, C.-C.; Ee, M.S.; Hollas, D. Does Medical Tourism Promote Economic Growth? A Cross-Country Analysis. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, H.; Kaufmann, E.L. Wellness tourism: Market analysis of a special health tourism segment and implications for the hotel industry. J. Vacat. Mark. 2001, 7, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Lanlung, C.; Kim, E.; Tang, L.R.; Song, S.M. Towards quality of life: The effects of the wellness tourism experience. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 410–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-Y. Value as a medical tourism driver. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2012, 22, 465–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, C.; Ham, S. Medical hotels in the growing healthcare business industry: Impact of international travelers’ perceived outcomes. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1869–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.-J.; Kim, H.-K.; Lee, T. Visitor motivational factors and level of satisfaction in wellness tourism: Comparison between first-time visitors and repeat visitors. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, V.A.; Turner, L.; Snyder, J.; Johnston, R.; Kingsbury, P. Promoting medical tourism to India: Messages, images, and the marketing of international patient travel. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kiatkawsin, K.; Jung, H.; Kim, W. The role of wellness spa tourism performance in building destination loyalty: The case of Thailand. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansari, A.; Kumar, V. Customer engagement: The construct, antecedents, and consequences. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, J.; Lemon, K.N.; Mittal, V.; Nass, S.; Pick, D.; Pirner, P.; Verhoef, P.C. Customer engagement behavior: Theoretical foundations and research directions. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Reinartz, W.J.; Krafft, M. Customer engagement as a new perspective in customer management. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivek, S.D.; Beatty, S.E.; Morgan, R.M. Customer engagement: Exploring customer relationships beyond purchase. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2012, 20, 122–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, K.K.F.; King, C.; Sparks, B.A.; Wang, Y. The role of customer engagement in building consumer loyalty to tourism brands. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J.; Falk, J. Visitors’ learning for environmental sustainability: Testing short-and long-term impacts of wildlife tourism experiences using structural equation modelling. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1243–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrigan, P.; Evers, U.; Miles, M.; Daly, T. Customer engagement with tourism social media brands. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistilis, N.; Buhalis, D.; Gretzel, U. Future eDestination marketing: Perspective of an Australian tourism stakeholder network. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 778–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Chiang, L.; Tang, L. Investigating wellness tourists’ motivation, engagement, and loyalty: In search of the missing link. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nangpiire, C.; Silva, J.; Alves, H. Customer engagement and value co-creation/destruction: The internal fostering and hindering factors and actors in the tourist/hotel experience. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Liu, B.; Li, Y. Tourist inspiration: How the wellness tourism experience inspires tourist engagement. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2021, forthcoming, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, K.K.F.; King, C.; Sparks, B.A.; Wang, Y. The influence of customer brand identification on hotel brand evaluation and loyalty development. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, E.C.; Holbrook, M.B. Hedonic consumption: Emerging concepts, methods and propositions. J. Mark. 1982, 46, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.-H.; Chang, F.-H.; Liu, F.-Y. Wellness tourism among seniors in Taiwan: Previous experience, service encounter expectations, organizational characteristics, employee characteristics, and customer satisfaction. Sustainability 2015, 7, 10576–10601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Kim, J.; Lee, C.-K.; Hickerson, B. The role of functional and wellness values in visitors’ evaluation of spa experiences. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 20, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloemer, J.; De Ruyter, K.; Wetzels, M. Linking perceived service quality and service loyalty: A multi-dimensional perspective. Eur. J. Mark. 1999, 33, 1082–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M.K.; Knight, G.A.; Cronin Jr, J.J.; Tomas, G.; Hult, M.; Keillor, B.D. Removing the contextual lens: A multinational, multi-setting comparison of service evaluation models. J. Retail. 2005, 81, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz, Y.; Jamshidi, D. Service quality evaluation and the mediating role of perceived value and customer satisfaction in customer loyalty. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2018, 4, 220–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, L.A.; Stephens, N. Effects of relationship marketing on satisfaction, retention, and prices in the life insurance industry. J. Mark. Res. 1987, 24, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, R.T.; Zahorik, A.J.; Keiningham, T.L. Return on quality (ROQ): Making service quality financially accountable. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garbarino, E.; Johnson, M.S. The different roles of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in customer relationships. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R.; Chen, X. The effects of perceived service quality on repurchase intentions and subjective well-being of Chinese tourists: The mediating role of relationship quality. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyffenegger, B.; Krohmer, H.; Hoyer, W.D.; Malaer, L. Service brand relationship quality: Hot or cold? J. Serv. Res. 2015, 18, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kiatkawsin, K.; Kim, W.; Lee, S. Investigating customer loyalty formation for wellness spa: Individualism vs. collectivism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 67, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Customer retention in the medical tourism industry: Impact of quality, satisfaction, trust, and price reasonableness. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Bhagwat, Y. Listen to the customer. Mark. Res. 2010, 22, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Marketing Science Institute. 2010–2012 Research Priorities. Available online: http://www.msi.org/research/index.cfm?id¼271 (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- Lemon, K.N.; Verhoef, P.C. Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L. Exploring customer brand engagement: Definition and themes. J. Strateg. Mark. 2011, 19, 555–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.J.J.D.S.S. On the concept of trust. Decis. Support Syst. 2002, 33, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zillifro, T.; Morais, D.B. Building customer trust and relationship commitment to a nature-based tourism provider: The role of information investments. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2004, 11, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, C.; Deshpande, R.; Zaltman, G. Factors affecting trust in market research relationships. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wirtz, J.; Lwin, M.O. Regulatory focus theory, trust, and privacy concern. J. Serv. Res. 2009, 12, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Fu, S.; Sun, J.; Bilgihan, A.; Okumus, F. An investigation on online reviews in sharing economy driven hospitality platforms: A viewpoint of trust. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-H.; Chang, C.-M. The influence of trust and perceived playfulness on the relationship commitment of hospitality online social network-moderating effects of gender. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 924–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suess, C.; Baloglu, S.; Busser, J.A. Perceived impacts of medical tourism development on community wellbeing. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Image congruence and relationship quality in predicting switching intention: Conspicuousness of product use as a moderator variable. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2013, 37, 303–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.M.; Ilkan, M. Impact of online WOM on destination trust and intention to travel: A medical tourism perspective. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2016, 5, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. The healthcare hotel: Distinctive attributes for international medical travelers. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustin, C.; Singh, J. Curvilinear effects of consumer loyalty determinants in relational exchanges. J. Mark. Res. 2005, 42, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, H.; Woo, E.; Uysal, M. Tourism experience and quality of life among elderly tourists. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.; Abdullah, J. Holidaytaking and the sense of well-being. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F.; Uysal, M. Social involvement and park citizenship as moderators for quality-of-life in a national park. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.M.; Lucas, R.E.; Smith, H.L. Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J.; Woo, E.; Kim, H.L. Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losier, G.F.; Bourque, P.E.; Vallerand, R.J. A motivational model of leisure participation in the elderly. J. Psychol. 1993, 127, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Li, X.; Morrison, A.M.; Wu, B. Social media micro-film marketing by Chinese destinations: The case of Shaoxing. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, P.; Siu, N.Y.-M. Servicescape elements, customer predispositions and service experience: The case of theme park visitors. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeoğlu, B.B.; Okumus, F.; Yi, X.; Jin, W. Do tourists’ personality traits moderate the relationship between social media content sharing and destination involvement? J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 612–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, S.W.; Goldsmith, R.E.; Pan, B. A retrospective view of electronic word-of-mouth in hospitality and tourism management. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suttikun, C.; Chang, H.J.; Bicksler, H. A qualitative exploration of day spa therapists’ work motivations and job satisfaction. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 34, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasikorn Research Center. Thailand’s Wellness and Medical Tourism. Available online: https://www.kasikornbank.com/international-business/en/Thailand/Intelligence/Pages/201804_Thailand_Medical_Tourism.aspx (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Kucukusta, D.; Pang, L.; Chui, S. Inbound Travelers’ Selection Criteria for Hotel Spas in Hong Kong. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heung, V.C.S.; Kucukusta, D.; Song, H. Medical tourism development in Hong Kong: An assessment of the barriers. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 995–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.W.; Yim, C.K.; Lam, S.S. Is customer participation in value creation a double-edged sword? Evidence from professional financial services across cultures. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J.; Taylor, S.A. Measuring service quality: A reexamination and extension. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, C.K.; Chan, K.W.; Lam, S.S.K. Do Customers and Employees Enjoy Service Participation? Synergistic Effects of Self- and Other-Efficacy. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Kruger, P.S.; Lee, D.-J.; Yu, G.B. How does a travel trip affect tourists’ life satisfaction? J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Assumptions and comparative strengths of the two-step approach: Comment on Fornell and Yi. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 20, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Bearden, W.O.; Sharma, S. Scaling Procedures: Issues and Applications; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Fairchild, A.J.; Fritz, M.S. Mediation analysis. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with LISREL, PRELIS, and SIMPLIS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rather, R.A.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Islam, J.U. Tourism-based customer engagement: The construct, antecedents, and consequences. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 39, 519–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Ilic, A.; Juric, B.; Hollebeek, L. Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: An exploratory analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Law, R.; Hung, K.; Guillet, B.D. Consumer trust in tourism and hospitality: A review of the literature. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2014, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.U.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Rahman, Z.; Khan, I.; Rasool, A. Customer engagement in the service context: An empirical investigation of the construct, its antecedents and consequences. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-W.; Teng, H.-Y.; Chen, C.-Y. Unlocking the customer engagement-brand loyalty relationship in tourism social media: The roles of brand attachment and customer trust. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abror, A.; Wardi, Y.; Trinanda, O.; Patrisia, D. The impact of Halal tourism, customer engagement on satisfaction: Moderating effect of religiosity. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Md Noor, S.; Schuberth, F.; Jaafar, M. Investigating the effects of tourist engagement on satisfaction and loyalty. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 39, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R.A. Consequences of consumer engagement in service marketing: An empirical exploration. J. Glob. Mark. 2019, 32, 116–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, D.; Curran, R.; O’Gorman, K.; Taheri, B. Visitors’ engagement and authenticity: Japanese heritage consumption. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Constructs and Items | M | SD | FL | AVE | CR | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service Quality | 5.85 | 1.20 | 0.81 | 0.93 | 0.93 | |

| Overall, the quality of this health and wellness service is excellent. | 0.86 | |||||

| Overall, the quality of this health and wellness service is superior. | 0.96 | |||||

| Overall, the quality of this health and wellness service is high standard. | 0.88 | |||||

| Satisfaction | 4.85 | 1.08 | 0.75 | 0.89 | 0.89 | |

| I am satisfied with the services provided. | 0.86 | |||||

| The wellness and health of this service meet my expectations. | 0.89 | |||||

| Overall, I am satisfied with the wellness and health provided by this service. | 0.84 | |||||

| Trust | 4.89 | 0.91 | 0.70 | 0.96 | 0.87 | |

| These wellness and health services meet my expectations. | 0.80 | |||||

| I feel confident with this wellness and health service. | 0.87 | |||||

| I will not be disappointed with this wellness and health service. | 0.81 | |||||

| This wellness and health service would be honest and sincere in addressing my concerns. | 0.69 | |||||

| I could rely on this wellness and health service to solve my wellness and health problems. | 0.61 | |||||

| These wellness and health services would make any effort to satisfy me. | 0.55 | |||||

| Customer Engagement | 4.56 | 1.03 | 0.62 | 0.87 | 8.12 | |

| I put a lot of effort into expressing my personal needs to the staff during the service process. | 0.82 | |||||

| I have a high level of participation in the service process. | 0.75 | |||||

| I am very much involved in deciding how the services should be provided. | 0.74 | |||||

| Quality of Life | 4.94 | 1.03 | 0.71 | 0.91 | 0.86 | |

| Feeling mentally recharged after the service. | 0.87 | |||||

| Feeling that own health improved because the service required physical activity. | 0.90 | |||||

| Judging that the service was well worth the money spent. | 0.75 | |||||

| Spending money specifically saved for service. | 0.55 | |||||

| Experience Extension | 4.52 | 1.42 | 0.76 | 0.93 | 0.87 | |

| I used social media to interact with friends about this service. | 0.82 | |||||

| I used social media to tell others about this service. | 0.93 | |||||

| I posted/shared photos/videos for friends/family, and acquaintances on social media (e.g., Facebook). | 0.74 |

| AVE | SQ | SAT | TR | CE | QOL | EE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service Quality (SQ) | 0.81 | 0.90 | |||||

| Satisfaction (SAT) | 0.75 | 0.39 | 0.87 | ||||

| Trust (TR) | 0.70 | 0.46 | 0.81 | 0.84 | |||

| Customer Engagement (CE) | 0.62 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.79 | ||

| Quality of Life (QOL) | 0.71 | 0.38 | 0.48 | 0.53 | 0.32 | 0.84 | |

| Experience Extension (EE) | 0.76 | 0.46 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.37 | 0.87 |

| Components and Manifest Variables | FL | AVE | CR | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service Evaluation | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.55 | |

| Service quality | 0.70 | |||

| Customer satisfaction | 0.55 |

| Hypothesis | Independent Variables | Regression Weights (β) | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Indirect | Total | |||

| Experience Extension (R2 = 0.782) | |||||

| H9 | Trust | −0.04 | −0.04 | Not supported | |

| H8 | Quality of life | 0.19 ** | 0.19 ** | Supported | |

| H3 | Service evaluation | 0.32 ** | 0.05 | 0.37 ** | Supported |

| H2 | Customer engagement | 0.10 | 0.15 ** | 0.25 ** | Not supported |

| Quality of life (R2 = 0.743) | |||||

| H7 | Customer engagement | 0.15 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.29 ** | Supported |

| H6 | Service evaluation | 0.42 ** | 0.42 ** | Supported | |

| Trust (R2 = 0.539) | |||||

| H5 | Service evaluation | 0.63 ** | 0.63 ** | Supported | |

| H4 | Customer engagement | 0.04 | 0.21 ** | 0.25 ** | Not supported |

| Service evaluation (R2 = 0.997) | |||||

| H1 | Customer engagement | 0.33 ** | 0.33 ** | Supported | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meeprom, S.; Chancharat, S. Building Health and Wellness Service Experience Extension: A Case Study of Bangkok, Thailand. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11691. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811691

Meeprom S, Chancharat S. Building Health and Wellness Service Experience Extension: A Case Study of Bangkok, Thailand. Sustainability. 2022; 14(18):11691. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811691

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeeprom, Supawat, and Surachai Chancharat. 2022. "Building Health and Wellness Service Experience Extension: A Case Study of Bangkok, Thailand" Sustainability 14, no. 18: 11691. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811691