What Is the Relationship between Collective Memory and the Commoning Process in Historical Building Renovation Projects? The Case of the Mas di Sabe, Northern Italy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

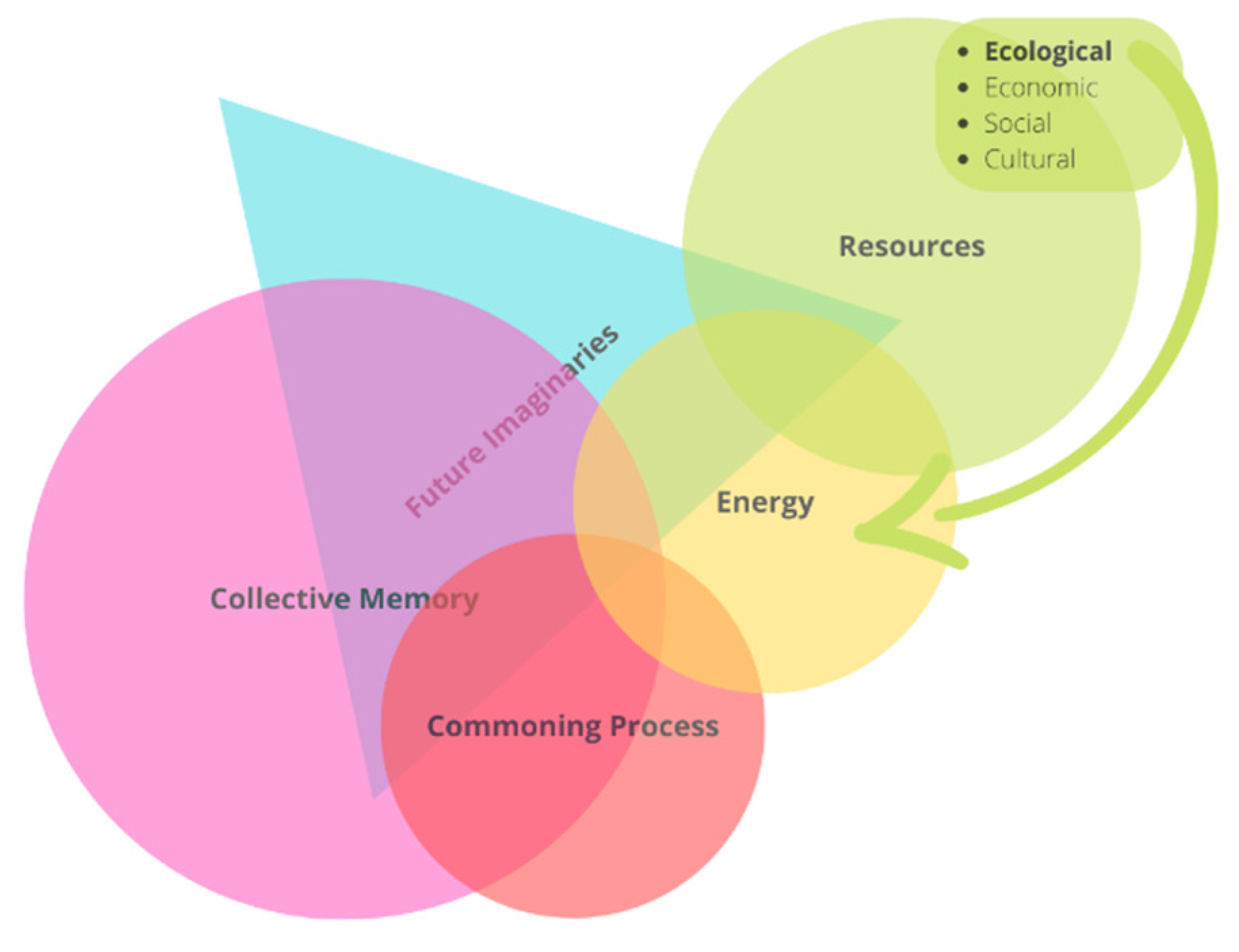

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Shelter Project

2.2. The Case Study

2.3. Semi-Structured Interviews

- Can you tell me how long you have lived in Zoldo’s community (or how long are you interested in this area)?

- Do you know the Mas di Sabe? If so, would you describe it?

- How do you figure the Mas di Sabe’s future?

- Which resources to produce renewable energy for the Mas di Sabe are available in the territory? What type of renewable energy might be produced?

- Which type of energy and how much electricity and thermal energy would be necessary for supporting Mas di Sabe’s future uses?

- Could you tell me about your best memory concerning the Mas di Sabe (or the surrounding territory)?

- Could you indicate another person who might be interested in this interview?

2.4. Method for Content Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Future Visions

[…] I imagine it [the Mas di Sabe] as a place that needs to be preserved since it represents the history of our territory and, thus, kept it as it is. I mean—if it’s possible—we should renovate the damaged parts and preserve the building as a witness—let’s say—of the agricultural activity and the handcrafters that used to work in the iron industry. […] I think it is necessary also to renovate the surrounding field and bring it back as it was, no? […] also cultivating some plants there to illustrate how the tabià looked back then.

[…] in this area, many tabià were built. However, our kids don’t know their history anymore; it has been lost in the collective memory because the territory lost those elements that help us remember our history. (SIM)

[…] a reference point of the Dolomiti-UNESCO Foundation… where organize events… of course, when it’d be possible to renovate the interiors because first the exteriors need to be renovated and… becoming… according to us… something symbolic, for events. I’m not talking about a dance party [laugh] but something joyful, an exhibition, a local market, bringing it back to life and turning it into a meeting place. (ECAF)

Mh… it could be a […] for cultural activities since Val di Zoldo organizes them… like concerts, theater, and readings. (DDDF)

I think it could be used for small and specific cultural activities… for example, I know that the Proloco [local cultural association] organized some itinerant shows, which also stopped at the Mas di Sabe where some theatrical gags were played. (AZF)

We think that the Mas di Sabe could be used as an eco-museum where visitors can see how the barn was built—considering that it’s the last of its kind in Zoldo—and we might create an exhibition hall to show the tabià’s history, […] also creating a room […] where kids might experience the mountain. Therefore, we can make expositions and project videos and, at the same time, make them build and play with materials linked to the mountain. […] and maybe also […] use that room to educate people on the dangers and the mountain world in general, in a suitable way for kids.

[…] we imagine the building with expositions of technical sheets explaining how barns were built in Zoldo. (MBF)

I think it could also be a study center of… the emigration phenomenon… the mountain areas, the Dolomiti… the tradition, and the depopulation and repopulation of the Dolomiti, something like this. (ECM)

It would be nice if both locals and externals could enjoy the Mas di Sabe; in this way, the externals could explore how people in ancient times lived the mountain. I thought that maybe—I guess I saw it abroad—we could organize some days where people can live again the time past […] people coming from Milan could spend a weekend with a local guide who explains to them everything about that life, so you can sleep there, eat there, also with the animals. (FPMM)

[…] I prefer to keep it as it is… without additional parts and preserve its original essence, structure, and purpose. If someone decides to turn it upside-down or amplify the building, it would not be a witness of the past anymore; instead, it would become another thing. (CGM)

And… then, maybe our imagination is of including the Mas di Sabe in an itinerary so you can go there and visit it and… very quietly, tiptoe, moving away [laugh]. (PBF)

[…] according to soft tourism, tourism of… silence, contemplation, which is what people ask in the mountain, they don’t want crowds, instead... in this way, people could be alone, or with few persons, for learning, admiring, contemplating, and so on. (ECAF)

I imagine it as a place where every activity respects the […], silence, environment […]. If there will be cultural or even touristic activities, they shouldn’t aim at a profit. Instead, this place should be for people to meet with a rhythm that […] should be less chaotic, and not of those cultural and touristic activities where people are encouraged to consume. (DDDF)

I also thought about an astronomic observatory, but we should ask the experts. (MBF)

3.2. Collective Memory

When we were kids, I remember we used to go there with our school. The teachers—and also some elderly of the area that decided to join us—used to tell us stories about how the building was structured, all parts’ functions… of course for us it was a trip, so we used to listen but also play and eat on the field [laugh], and after that go back home. (LDRF)

When I saw the Mas di Sabe for the first time, it appeared to me like an enchanted place, a place where you can take your time… you can go there and read, write, sing, draw… or you can chat with someone; a place where you stay gladly. There are some places with that kind of… attraction. That’s how it began, and since then, the Mas di Sabe has this meaning for me… it’s characteristic, and also, somehow [smile]—if I may say—it’s magical. (CGM)

When you arrive in the village [Costa], you are always curious to see the Mas di Sabe. You take a walk and watch the landscape, you go there, and it helps you relax, regenerate, and then you go home. It feels… somehow, like a medicine… it’s like a therapeutic place. (ECM)

It’s a special place. I mean, when you’re there, your heart opens up. (FMPM)

Every time I… I go there, I feel that I’m in a special place. I mean… the feeling of isolation and estrangement from personal issues, together with your memories [connection problems] … and different feelings of joy, worry of a community it’s something that always touched me. Because it’s an identity place, I always feel the need to go there and re-assimilate a tiny part of that identity, which is not mine anymore since I’ve been living in Venice for many years now […]. (FAM)

[…] [the Mas di Sabe] always represented some sort of identity, of cultural identity. In fact, in the XIX century, it was used as a gathering place during summer [a dance hall]; it was a place of identification and social aggregation. For me, it’s fundamental that even today, for the inhabitants… the local community, the Mas di Sabe is an identity place. Thus, both the building and the surroundings represent the history of this valley. (FAM)

In “Pelmo d’altri tempi” [Giovanni Angelini, 2008. Nuovi Sentieri], the author reports pictures of the Mas di Sabe, which was intact at that time. Moreover, he tells the legends that the local people created on the ancient barn. He states what we all know nowadays: the Mas di Sabe had a substantial identity value […]. (ECAF)

[…] for example, a legend says that the Mas di Sabe was a house for rich dames who owned precious marriage chests, which are enormous rocks that fell from Pelmo since everything happened under the shadow of this beautiful and peculiar mountain. During mass on Sundays, everybody waited for the dames who came by carriages… to attend the mass. Another legend refers that those dames had low-necked gowns, which means they were [laugh], you know? Many legends and stories about the Mas di Sabe have been created because the building means something to locals; it’s not a random place. (ECAF)

Coming from Iral, there’s a path in the forest [the mulattiera], and… there’s a legend to which I’m attached. Zoldo has some legends regarding mysterious characters who weren’t magicians, fairies, or nymphs […]. They were dames, characters that belonged to ancient times. Some say they were miner’s companions, other nobles and that they had carriages, horses and used to turn furiously around the Mas di Sabe—coming from Iral through the forest—I’d say because they were bored. Doing so, they made circular marks still visible [laugh], namely if you go in the wood there’s a groove with a slight rise part like a bump, which makes your imagination run wild since, you know, the witches’ sabbath and so on. (PBF)

3.3. Commoning Process

One may involve the local population through cultural associations that manage the municipalization process directly because I believe that we can only give people the chance to use the building but if the locals don’t participate through territorial organizations and the existing associations… […] I mean, for me is essential that people got involved because they feel that the building belongs to them. In this way, it’s possible to think about a future for the Mas di Sabe that overcomes its original purpose. (FAM)

Of course, it’s necessary to… make it available for the community and… find a usage that fits the current time. I mean, it’s essential not just to renovate the building and keep it closed, turning it into another cathedral of the desert… but… it should be accessible for communal and social uses. (CGM)

[I spoke with] *** and *** […] and we asked some questions, you know? Then I called the mayor to understand the progress of the building’s municipalization. (MBF)

[…] of course, once they [the local administration] found an architect and planned the renovation, we need to discuss and decide before they start working. Otherwise, we are forced to adapt, no? I believe… or better…*** asked me if we could meet again all together, no? A meeting… also with *** that has clear ideas on the project. (MBF)

[…] Then I think it is fairer if it’s the administration, the people, to choose how to put the ideas into practice… the essential thing is to save it [the Mas di Sabe], the way… for renovating it… I mean… which is the use… it’s vital that people express it… maybe through round table discussions, and meetings. (ECAF)

3.4. Energy

It depends on its [of the Mas di Sabe] future uses. If we use it as we’re doing right now, the energy won’t be necessary because [blurred word] it’s a small building, so it’d be necessary only to illuminate the interiors. (SIM)

Uhm… well, electricity… the minimum required. Honestly, I don’t think it needs a significant amount of electricity. (FMPM)

I would avoid electricity or any other energy. I mean, I’d keep it as it is. I would renovate it to prevent its collapse, but I would bring it back to the XVI century. (PBF)

I would never think about a photovoltaic installed on the structure, I mean, in many cases, it’s possible, but in cases like this one, I’d see it… difficult. It would be a sacrifice for Shelter’s purposes of safeguarding. (FAM)

Oh my God… [laugh] I’m smiling because here [in Veneto’s region] they [companies] dried out and spoiled all the streams with the excuse of renewable energy, I mean they built massive installations—by the way private—and they took away the watercourses from the valley, which were also a tourist attraction, so… I’d be careful in telling you about [laugh] renewable energy technologies. (MBF)

I don’t even know how to address this matter. We need to be careful about renewable energies because… well, the devil could hide behind them, creating environmental disasters and catastrophes that it’s better to avoid, no? So, for example, I refer to the hydroelectric or other activities that enrich only the promoters, which cling to subsidies… subsidies… and, thus, the renewable energies, ok. But they must be clarified, and well thought out. (SDZF)

I can tell you that […] in some places in Belluno’s province, some conflicts took place—some of them with positive results—regarding the usage of water for producing energy. And, of course, water is a renewable energy resource that implicates serious stuff, and we all know that thanks to the subsidies, and capitals of different kinds, European capitals, there was massive speculation on… the management of water as a resource, you know? for producing energy. So, well, obviously… this is something we need to consider. (DDDF)

3.5. Resources

Access to subsidies that support the local government in the renovation project (economic resources).

[…] We are at the starting point of the building’s renovation project. Having already acquired some properties through donations and having access to Shelter’s subsidies allows us to maintain the surrounding, no? However, after planning it, we’ll have to find a more significant contribution that will enable us to undertake the renovation in the forthcoming months and years. Because today we have some resources for supporting it physically, but currently we don’t have resources for renovating the building. Moreover, nowadays, the lack of resources limits even the energy issue. (SDZM)

Associations that promote activities and stimulate participation and access to the building (social resources).

[…] we founded the association in 2012, but we were more active in the early years—as I love to say—of the ‘Third Millenium’. We also had a positive reaction from the administration, which saw us being active on the territory, so it was assigned to us a headquarters […] free of charge. (PBF)

Cultural activities that are already available in the territory (cultural resources).

[…] there are some… small, well… let’s call them museums in the valley and… yes, with—I don’t know—maybe three or four exposition halls, that concern… themes… yes, for example, one of them concerns the manufacture of iron and nails, you know? That was one of the ancient activities in the valley. (LDRF)

Environmental heritage and local natural resources that might serve renewable energy to the building (ecological resources).

It’s a beautiful place because there is a vast field, there is the Civetta [mountain] on its front, the Pelmo [mountain] behind it, which make it a panoramic place […]. (AZF)

[…] solar energy might be certainly used. I don’t know about the wind. And… there is little water and… yes, I know there is a stream nearby, but I’m not sure it’s enough to produce energy. (CGM)

Otherwise… as a renewable resource, we have the wood from the forest that might be used for heating. (ECM)

[…] nearby there are no streams that allow the installation of a small hydroelectric plant… there’s something, but… it’s far away, maybe… sixty, seventy meters… that might be used for… creating a small waterfall that produces 1 KW of energy, that’s it. 1 KW or two max., because it has a limited flow rate. (SIM)

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baselice, A.; Lombardi, M.; Prosperi, M.; Stasi, A.; Lopolito, A. Key Drivers of the Engagement of Farmers in Social Innovation for Marginalised Rural Areas. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosworth, G.; Atterton, J. Entrepreneurial In-migration and Neoendogenous Rural Development. Rural Sociol. 2012, 77, 254–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewees, S.; Lobao, L.; Swanson, L.E. Local Economic Development in an Age of Devolution: The Question of Rural Localities. Rural Sociol. 2003, 68, 182–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumeier, S. Why do social innovations in rural development matter and should they be considered more seriously in rural development research?—Proposal for a stronger focus on social innovations in rural development research. Sociol. Rural. 2012, 52, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secco, L.; Pisani, E.; Burlando, C.; Christoforou, A. What Future for LEADER as a Catalyst of Social Innovation? In Social Capital and Local Development; Pisani, E., Franceschetti, G., Secco, L., Christoforou, A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 417–438. [Google Scholar]

- Pedroli, B. Towards new common and sharing interest in the landscape integrating natural and cultural heritage. Ex Novo J. Archeol. 2019, 4, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noak, A.; Federwisch, T. Social Innovation in Rural Regions: Older Adults and Creative Community Development. Rural Sociol. 2020, 85, 1021–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewanski, R. La Prossima Democrazia: Dialogo—Deliberazione—Decisione. 2016. Available online: https://www.cantierememoria.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Rodolfo-Lewanski_Laprossimademocrazia.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- López Cerezo, J.A.; Gonzáles, G. Lay knowledge and public participation in technological and environmental policy. Sci. Philos. Technol. Q. Electron. J. 1996, 2, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, N.; Rasouli, M.; Azhdai, B. The Attitude of the Local Community to the Impact of Building Reuse: Three Cases in an Old Neighborhood of Tehran. Herit. Soc. 2019, 11, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, V. Commoning: On the Social Organisation of the Commons. Economics 2013, 16, 433–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkbrenner, B.J.; Roosen, J. Citizens’ willingness to participate in local renewable energy projects: The role of community and trust in Germany. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 13, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisbois, M.C. Powershifts: A framework for assessing the growing impact of decentralised ownership of energy transitions on political decision-making. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 50, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stobbelaar, D.J.; Pedroli, B. Perspectives on landscape identity: A conceptual challenge. Landsc. Res. 2011, 36, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, B.S.; Stedman, R.C. A Comparative Analysis of Predictors of Sense of Place Dimensions: Attachment to, Dependence on, and Identification with Lakeshore Properties. J. Environ. Manag. 2006, 79, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olwig, K. Place contra space in a morally just landscape. Nor. J. Geogr. 2006, 60, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshansky, H.M.; Fabian, A.K.; Kaminoff, R. Place-identity: Physical world socialisation of the self. J. Environ. Psychol. 1983, 3, 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skogheim, R.; Simon, V.K.; Gao, L.; Dietze-Schirdewahn, A. Place identity with a historic landscape—An interview-based case study of local residents’ relationship with the Austrått Landscape in Norway. Herit. Soc. 2018, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schama, S. Landscape and Memory, 1st ed.; Alfred a Knopf Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Xavier, G. Is heritage an asset or a liability? J. Cult. Herit. 2004, 5, 301–309. [Google Scholar]

- Tassinari, P.; Torreggiani, D.; Benni, S.; Dall’Ara, E.; Pollicino, G. The FarmBuiLD model (farm building landscape design): First definition of parametric tools. J. Cult. Herit. 2011, 12, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, W. Cultural diversity, cultural heritage and human rights: Towards heritage management as human rights-based cultural practice. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2012, 18, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, M. Disciplining memory: Heritage tourism and the temporalisation of the built environment in rural France. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2009, 15, 76–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benni, S.; Carfagna, E.; Torreggiani, D.; Maino, E.; Bovo, M.; Tassinari, P. Multidimensional measurement of the level of consistency of farm buildings with rural heritage: A methodology tested on an Italian case study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sandström, E.; Ekman, A.K.; Lindholm, K.J. Commoning in the periphery—The role of the commons for understanding rural continuities and change. Int. J. Commons 2017, 11, 508–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linebaugh, P. Magna Carta Manifesto: Liberties and Commons for All, 1st ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- De Angelis, M.; Harvie, D. The commons. In The Routledge Companion to Alternative Organisation, 1st ed.; Parker, M., Cheney, G., Fournier, V., Land, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 280–294. [Google Scholar]

- Sardaro, R.; La Sala, P.; De Pascale, G.; Faccilongo, N. The conservation of cultural heritage in rural areas: Stakeholder preferences regarding historical rural buildings in Apulia, southern Italy. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessière, J. Local development and heritage: Traditional food and cuisine as tourist attractions in rural areas. Sociol. Rural. 1998, 38, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.A.; Hasshim, S.A.; Rozali, R. Residents’ preference on conservation of the Malay Traditional Village in Kampong Morten, Malacca. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 202, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coeterier, J.F. Lay peoples’ evaluation of historic sites. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2002, 59, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbwachs, M.; Ditter, F.J.; Ditter, V.Y. The Collective Memory, 1st ed.; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J.D.; Weigert, A. Trust as a Social Reality. Soc. Forces 1981, 63, 967–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licata, L.; Mercy, A. Collective memory, social psychology of. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Wright, J.D., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2015; Volume 4, pp. 194–199. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, O.; Licata, L.; Van der Linden, N.; Mercy, A.; Luminet, O. A waffle-shaped model for how realistic dimensions of the Belgian conflict structure collective memories and stereotypes. Mem. Stud. 2011, 5, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J.S. Acts of Meaning, 1st ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, M.T.G.; Silva, B.C.P.; Oliveira, H.M.; Fidelis, P.A. A importância da Sustentabilidade na Restauração do Patrimônio Histórico. Estudo de caso: Pontes; Construindo: Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2018; Volume 10, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Norrström, H. Sustainable and balanced energy efficiency and preservation in our built heritage. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2623–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, M.J. Buildings as history: The place of collective memory in the study of historic preservation. Symb. Interact. 2007, 30, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbetta, P. Social Research. Theory, Methods and Techniques, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Poggi, F.; Firmino, A.; Amado, M. Shaping energy transition at municipal scale: A net-zero energy scenario-based approach. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balest, J.; Hrib, M.; Dobšinskác, Z.; Paletto, A. The formulation of the National Forest Programme in the Czech Republic: A qualitative review. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 89, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balest, J.; Magnani, N. Contesto socio-culturale ed efficienza energetica nell’abitazione. Sociol. Urbana E Rural. 2021, 124, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, N.; Cittati, V.-M. Combining the multilevel perspective and socio-technical imaginaries in the study of community energy. Energies 2022, 15, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, M.J. The significance of saturation. Qual. Health Res. 1995, 5, 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbwachs, M. Les Cadres Sociaux de la Mémoire, 1st ed.; Felix, A., Ed.; Bibliothèque de philosophie contemporaine: Paris, France, 1925. [Google Scholar]

| Stakeholders | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Institutions | Regional and local level |

| Associations | Cultural, touristic, research |

| Companies | Touristic, agricultural |

| Citizens | Inhabitants, emigrants, natives |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cittati, V.-M.; Balest, J.; Exner, D. What Is the Relationship between Collective Memory and the Commoning Process in Historical Building Renovation Projects? The Case of the Mas di Sabe, Northern Italy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11870. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911870

Cittati V-M, Balest J, Exner D. What Is the Relationship between Collective Memory and the Commoning Process in Historical Building Renovation Projects? The Case of the Mas di Sabe, Northern Italy. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):11870. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911870

Chicago/Turabian StyleCittati, Valentina-Miriam, Jessica Balest, and Dagmar Exner. 2022. "What Is the Relationship between Collective Memory and the Commoning Process in Historical Building Renovation Projects? The Case of the Mas di Sabe, Northern Italy" Sustainability 14, no. 19: 11870. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911870

APA StyleCittati, V. -M., Balest, J., & Exner, D. (2022). What Is the Relationship between Collective Memory and the Commoning Process in Historical Building Renovation Projects? The Case of the Mas di Sabe, Northern Italy. Sustainability, 14(19), 11870. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911870