Advanced Bioethanol Production from Source-Separated Bio-waste in Pilot Scale

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Analytical Methods

2.3. Experimental Methods

2.3.1. Lab-Scale

2.3.2. Bench-Scale

2.3.3. Pilot-Scale

3. Results

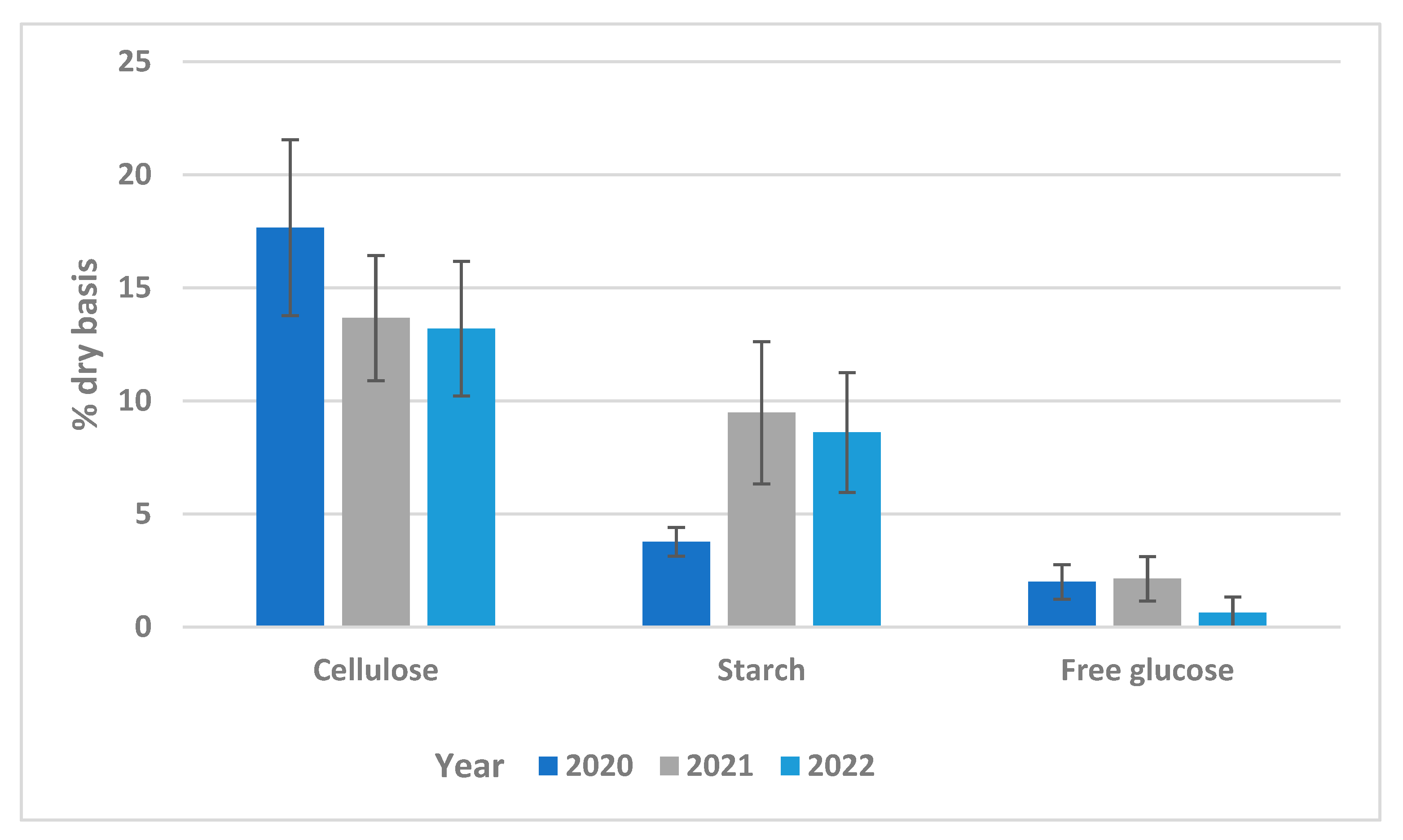

3.1. Raw Material

3.2. Lab-Scale

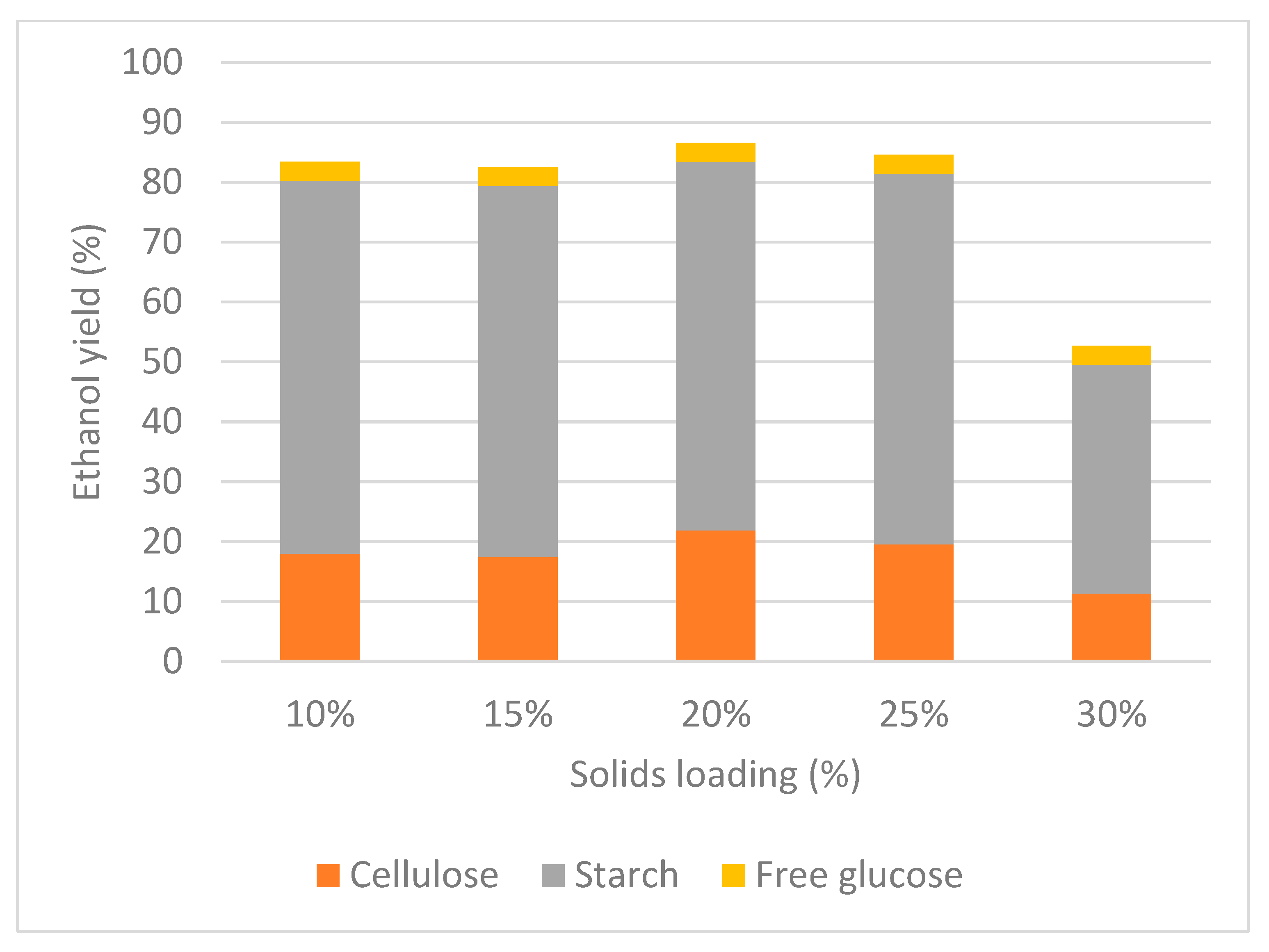

3.3. Bench-Scale

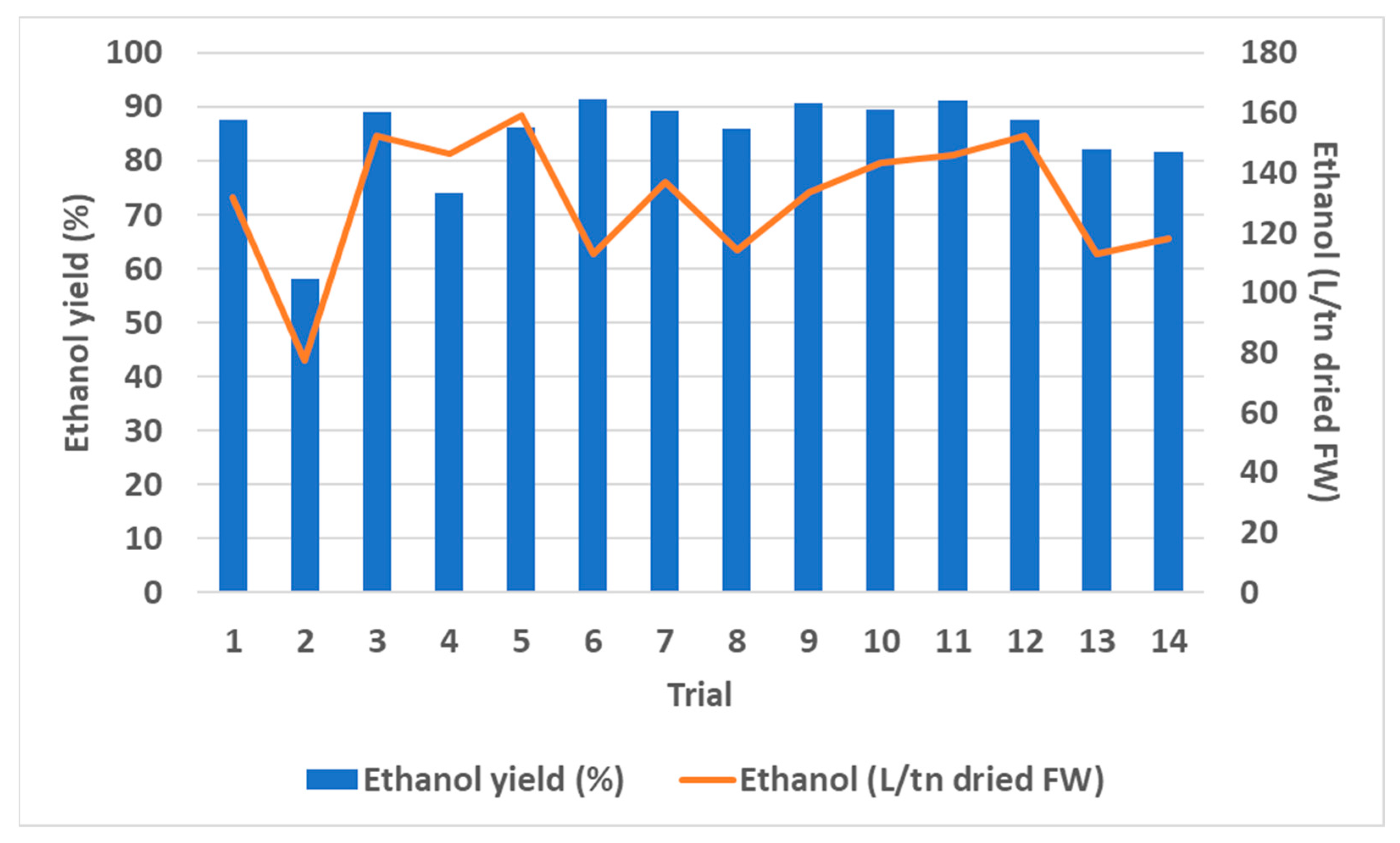

3.4. Pilot Plant

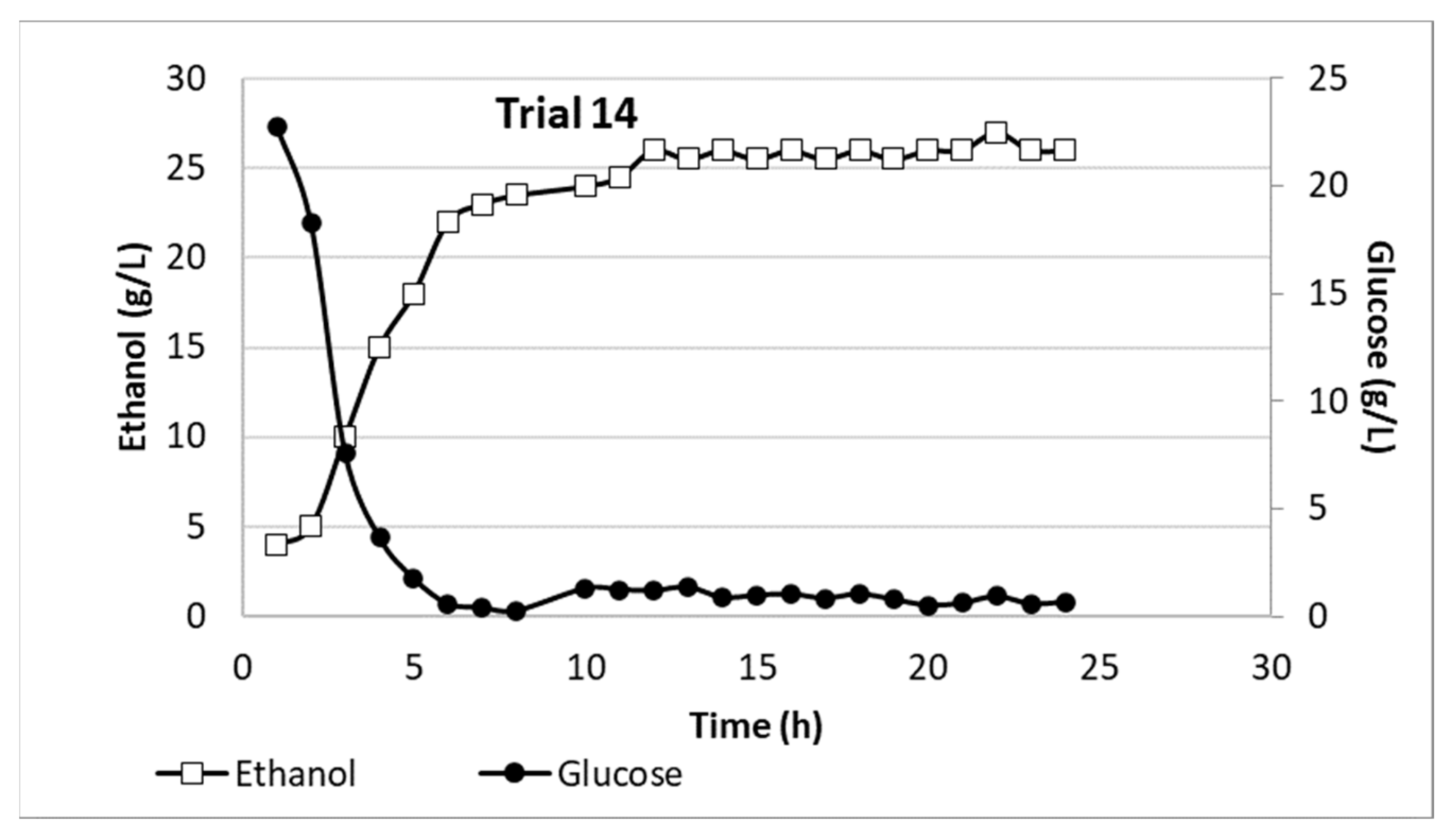

3.4.1. Bioconversion Process

3.4.2. Ethanol Recovery

4. Conclusions

- the yield of ethanol production was 86.6 ± 4.9%;

- the degradation of starch was very high equal to 94.6 ± 2.4%; and

- the degradation of cellulose was measured equal to 76.8 ± 5.2%.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The European Food Information Council (EUFIC). Food Waste in Europe: Statistics and Facts about the Problem. 2021, pp. 1–7. Available online: https://www.eufic.org/en/food-safety/article/food-waste-in-europe-statistics-and-facts-about-the-problem (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Sönnichsen, N. Fuel Ethanol Production Worldwide in 2021, by Country. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/281606/ethanol-production-in-selected-countries/ (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Rosales-Calderon, O.; Arantes, V. A Review on Commercial-Scale High-Value Products That Can Be Produced alongside Cellulosic Ethanol. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2019, 12, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschnitz-Garbers, M.; Gosens, J. Producing Bio-Ethanol from Residues and Wastes—A Technology with Enormous Potential in Need of Further Research and Development. Policy Brief 2015, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Barampouti, E.M.; Mai, S.; Moustakas, K.; Malamis, D.; Loizidou, M.; Passadis, K.; Stoumpou, V. Chapter 3—Advanced Bioethanol Production from Biowaste Streams. In Recent Advances in Renewable Energy Technologies; Jeguirim, M., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; Volume 2, pp. 77–154. ISBN 9780128235324. [Google Scholar]

- Haldar, D.; Shabbirahmed, A.M.; Singhania, R.R.; Chen, C.W.; Di Dong, C.; Ponnusamy, V.K.; Patel, A.K. Understanding the Management of Household Food Waste and Its Engineering for Sustainable Valorization- A State-of-the-Art Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 358, 127390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Zeng, H.; Wang, Z. Review on Technology of Making Biofuel from Food Waste. Int. J. Energy Res. 2022, 46, 10301–10319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Larroche, C.; Dussap, C.G. Comprehensive Assessment of 2G Bioethanol Production. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 313, 123630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barampouti, E.M.; Mai, S.; Malamis, D.; Moustakas, K.; Loizidou, M. Liquid Biofuels from the Organic Fraction of Municipal Solid Waste: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 110, 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devos, R.J.B.; Colla, L.M. Simultaneous Saccharification and Fermentation to Obtain Bioethanol: A Bibliometric and Systematic Study. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2022, 17, 100924. [Google Scholar]

- Alibardi, L.; Cossu, R. Composition Variability of the Organic Fraction of Municipal Solid Waste and Effects on Hydrogen and Methane Production Potentials. Waste Manag. 2015, 36, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntaikou, I.; Menis, N.; Alexandropoulou, M.; Antonopoulou, G.; Lyberatos, G. Valorization of Kitchen Biowaste for Ethanol Production via Simultaneous Saccharification and Fermentation Using Co-Cultures of the Yeasts Saccharomyces Cerevisiae and Pichia Stipitis. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 263, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.Y.; Kong, F.; Cui, Z.; Zhao, L.; Ma, J.; Ren, N.Q.; Liu, B.F. Cogeneration of Hydrogen and Lipid from Stimulated Food Waste in an Integrated Dark Fermentative and Microalgal Bioreactor. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 287, 121468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.Y.; Lam, H.P.; Karthikeyan, O.P.; Wong, J.W.C. Optimization of Food Waste Hydrolysis in Leach Bed Coupled with Methanogenic Reactor: Effect of PH and Bulking Agent. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 3702–3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junoh, H.; Yip, C.H.; Kumaran, P. Effect on Ca(OH)2 Pretreatment to Enhance Biogas Production of Organic Food Waste. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2016, 32, 012013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafid, H.S.; Abdul Rahman, N.; Md Shah, U.K.; Samsu Baharudin, A.; Zakaria, R. Direct Utilization of Kitchen Waste for Bioethanol Production by Separate Hydrolysis and Fermentation (SHF) Using Locally Isolated Yeast. Int. J. Green Energy 2016, 13, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavouraki, A.I.; Angelis, E.M.; Kornaros, M. Optimization of Thermo-Chemical Hydrolysis of Kitchen Wastes. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cekmecelioglu, D.; Uncu, O.N. Kinetic Modeling of Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Pretreated Kitchen Wastes for Enhancing Bioethanol Production. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 735–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, E.; Taheri, M.E.; Passadis, K.; Novacovic, J.; Barampouti, E.M.; Mai, S.; Moustakas, K.; Malamis, D.; Loizidou, M. Valorisation of Restaurant Food Waste under the Concept of a Biorefinery. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2020, 11, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uncu, O.N.; Cekmecelioglu, D. Cost-Effective Approach to Ethanol Production and Optimization by Response Surface Methodology. Waste Manag. 2011, 31, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunqing, Z.; Han, X.; Hui, J.; Weihua, Q. Enhance the Ethanol Fermentation Performance of Kitchen Waste Using Microwave Pretreatment. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, Y.; An, M.Z.; Tang, Y.Q.; Syo, T.; Osaka, N.; Morimura, S.; Kida, K. Production of Fuel Ethanol and Methane from Garbage by High-Efficiency Two-Stage Fermentation Process. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2009, 108, 508–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Wang, P.; Zhai, Z.; Yao, J. Fuel Ethanol Production from Concentrated Food Waste Hydrolysates in Immobilized Cell Reactors by Saccharomyces Cerevisiae H058. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2011, 86, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, J.C.; Pak, D. Feasibility of Producing Ethanol from Food Waste. Waste Manag. 2011, 31, 2121–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, H.C.; Song, I.S.; Kim, J.C.; Shirai, Y.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, J.K.; Chung, S.O.; Kim, D.H.; Oh, K.K.; Cho, Y.S. Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Food Waste and Ethanol Fermentation. Int. J. Energy Res. 2009, 33, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafid, H.S.; Nor ‘Aini, A.R.; Mokhtar, M.N.; Talib, A.T.; Baharuddin, A.S.; Umi Kalsom, M.S. Over Production of Fermentable Sugar for Bioethanol Production from Carbohydrate-Rich Malaysian Food Waste via Sequential Acid-Enzymatic Hydrolysis Pretreatment. Waste Manag. 2017, 67, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.K.; Oh, B.R.; Shin, H.J.; Eom, C.Y.; Kim, S.W. Statistical Optimization of Enzymatic Saccharification and Ethanol Fermentation Using Food Waste. Process Biochem. 2008, 43, 1308–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Storms, R.; Tsang, A. A Quantitative Starch-Iodine Method for Measuring Alpha-Amylase and Glucoamylase Activities. Anal. Biochem. 2006, 351, 146–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghose, T.K. Measurement of Cellulose Activities. Pure Appl. Chem. 1987, 59, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluiter, A.; Hames, B.; Ruiz, R.; Scarlata, C.; Sluiter, J.; Templeton, D.; Crocker, D. Determination of Structural Carbohydrates and Lignin in Biomass: Laboratory Analytical Procedure (LAP); NREL/TP-510-42618; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2012; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sluiter, A.; Hames, B.; Hyman, D.; Payne, C.; Ruiz, R.; Scarlata, C.; Sluiter, J.; Templeton, D.; Nrel, J.W. Determination of Total Solids in Biomass and Total Dissolved Solids in Liquid Process Samples; NREL/TP-510-42621; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2008; pp. 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sluiter, A.; Ruiz, R.; Scarlata, C.; Sluiter, J.; Templeton, D. Determination of Extractives in Biomass. Natl. Renew. Energy Lab. 2005, 12, 838–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 21st ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; 874p. [Google Scholar]

- Sofokleous, M.; Christofi, A.; Malamis, D.; Mai, S.; Barampouti, E.M. Bioethanol and Biogas Production: An Alternative Valorisation Pathway for Green Waste. Chemosphere 2022, 296, 133970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passadis, K.; Christianides, D.; Malamis, D.; Barampouti, E.M.; Mai, S. Valorisation of Source-Separated Food Waste to Bioethanol: Pilot-Scale Demonstration. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2022, 12, 4599–4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Bhadana, B.; Chauhan, P.S.; Adsul, M.; Kumar, R.; Gupta, R.P.; Satlewal, A. Understanding the Effects of Low Enzyme Dosage and High Solid Loading on the Enzyme Inhibition and Strategies to Improve Hydrolysis Yields of Pilot Scale Pretreated Rice Straw. SSRN Electron. J. 2022, 327, 125114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.L.; Jansen, J.L.C.; Davidsson, Å.; Christensen, T.H. Effects of Pre-Treatment Technologies on Quantity and Quality of Source-Sorted Municipal Organic Waste for Biogas Recovery. Waste Manag. 2007, 27, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakali, A.; MacRae, J.D.; Isenhour, C.; Blackmer, T. Composition and Contamination of Source Separated Food Waste from Different Sources and Regulatory Environments. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 314, 115043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alder, P.; Markova, E.V.; Granovsky, V. The Design of Experiments to Find Optimal Conditions a Programmed Introduction to the Design of Experiments; Mir Publishers: Moscow, Russia, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, W.G.; Cox, G.M. Experimental Designs, 2nd ed.; Sons, J.W., Ed.; John WIley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1957; ISBN 978-0471545675. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Gao, M.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Shirai, Y. Pilot-Scale Open Fermentation of Food Waste to Produce Lactic Acid without Inoculum Addition. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 104354–104358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingren, A.; Galbe, M.; Zacchi, G. Techno-Economic Evaluation of Producing Ethanol from Softwood: Comparison of SSF and SHF and Identification of Bottlenecks. Biotechnol. Prog. 2003, 19, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamanou, D.G.; Malamis, D.; Mamma, D.; Kekos, D. Bioethanol from Dried Household Food Waste Applying Non-Isothermal Simultaneous Saccharification and Fermentation at High Substrate Concentration. Waste Biomass Valorization 2015, 6, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruwajoye, G.S.; Sewsynker-Sukai, Y.; Kana, E.B.G. Valorisation of Cassava Peels through Simultaneous Saccharification and Ethanol Production: Effect of Prehydrolysis Time, Kinetic Assessment and Preliminary Scale Up. Fuel 2020, 278, 118351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, E.; Saragas, K.; Taheri, M.E.M.E.; Novakovic, J.; Barampouti, E.M.; Mai, S.; Moustakas, K.; Malamis, D.; Loizidou, M. The Role of Enzyme Loading on Starch and Cellulose Hydrolysis of Food Waste. Waste Biomass Valorization 2019, 10, 3753–3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, R.; Narisetty, V.; Nagarajan, S.; Agrawal, D.; Ranade, V.V.; Salonitis, K.; Venus, J.; Kumar, V. High-Level Fermentative Production of Lactic Acid from Bread Waste under Non-Sterile Conditions with a Circular Biorefining Approach and Zero Waste Discharge. Fuel 2022, 313, 122976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uçkun Kiran, E.; Liu, Y. Bioethanol Production from Mixed Food Waste by an Effective Enzymatic Pretreatment. Fuel 2015, 159, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konti, A.; Papagiannakopoulou, P.; Mamma, D.; Kekos, D.; Damigos, D. Ethanol Production from Food Waste in West Attica: Evaluation of Investment Plans under Uncertainty. Biofuels 2020, 11, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsakas, L.; Kekos, D.; Loizidou, M.; Christakopoulos, P. Utilization of Household Food Waste for the Production of Ethanol at High Dry Material Content. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2014, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taheri, M.E.; Salimi, E.; Saragas, K.; Novakovic, J.; Barampouti, E.M.; Mai, S.; Malamis, D.; Moustakas, K.; Loizidou, M. Effect of Pretreatment Techniques on Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Food Waste. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2021, 11, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Low Level (−) | High Level (+) | Center |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpirizymeXL (μL/g starch) | 20 | 60 | 40 |

| NS87014 (μL/g cellulose) | 100 | 250 | 175 |

| S. cerevisiae (% w/w) | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| % | Dry Basis (%) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batch | Date of Delivery | Moisture | Fats and Oil | Water Soluble Solids | Ash | Volatile Solids | Cellulose | Hemicellulose | Starch | Acid Soluble Lignin | Acid Insoluble Residue | Free Glucose |

| 1 | 15/9/2020 | 75.7 ± 1.1 | 11.0 ± 0.8 | 37.7 ± 0.5 | 11.7 ± 0.4 | 88.3 ± 0.4 | 13.6 ± 1.8 | 33.8 ± 1.1 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 9.2 ± 1.2 | 1.6 ± 0.5 |

| 2 | 29/9/2020 | 78.0 ± 0.9 | 13.0 ± 0.6 | 32.1 ± 2.6 | 13.3 ± 1.7 | 86.8 ± 1.7 | 19.7 ± 5.3 | 6.8 ± 1.5 | 2.9 ± 0.9 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 10.3 ± 1.2 | 1.6 ± 0.3 |

| 3 | 13/10/2020 | 76.2 ± 0.8 | 13.2 ± 0.3 | 35.2 ± 4.2 | 11.6 ± 0.5 | 88.4 ± 0.5 | 18.7 ± 3.8 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 4.5 ± 1.6 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 9.5 ± 1.4 | 2.6 ± 0.2 |

| 4 | 27/10/2020 | 76.8 ± 0.9 | 11.8 ± 0.5 | 35.0 ± 1.0 | 12.3 ± 0.2 | 87.7 ± 0.2 | 23.8 ± 1.5 | 4.4 ± 3.1 | 3.8 ± 0.8 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 9.5 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.0 |

| 5 | 24/11/2020 | 76.0 ± 0.7 | 8.8 ± 1.0 | 34.1 ± 0.8 | 12.6 ± 0.2 | 87.4 ± 0.2 | 16.2 ± 1.7 | 4.2 ± 1.1 | 4.5 ± 0.9 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 16.1 ± 0.5 | 2.8 ± 1.1 |

| 6 | 1/12/2020 | 75.1 ± 0.6 | 13.7 ± 1.9 | 37.7 ± 0.7 | 13.4 ± 0.4 | 86.6 ± 0.4 | 13.9 ± 0.9 | 3.9 ± 1.5 | 3.4 ± 2.4 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 6.6 ± 0.9 | 2.5 ± 1.1 |

| 7 | 26/1/2021 | 73.2 ± 0.7 | 13.6 ± 1.4 | 33.6 ± 1.0 | 7.4 ± 0.4 | 92.6 ± 0.4 | 15.4 ± 1.8 | 8.7 ± 1.8 | 7.4 ± 0.7 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 8.9 ± 0.4 | 3.9 ± 0.1 |

| 8 | 9/2/2021 | 72.6 ± 0.9 | 11.2 ± 2.1 | 25.5 ± 1.3 | 10.0 ± 2.4 | 90.0 ± 2.4 | 18.4 ± 2.4 | 8.7 ± 1.2 | 9.7 ± 2.7 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 13.2 ± 2.4 | 2.4 ± 0.2 |

| 9 | 20/4/2021 | 73.9 ± 0.8 | 14.6 ± 1.6 | 27.7 ± 0.7 | 7.5 ± 0.5 | 92.5 ± 0.5 | 16.0 ± 3.8 | 8.5 ± 0.7 | 10.4 ± 1.7 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 17.9 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 1.2 |

| 10 | 25/5/2021 | 71.5 ± 1.0 | 14.2 ± 1.0 | 26.8 ± 1.3 | 7.2 ± 2.6 | 92.8 ± 2.6 | 11.8 ± 2.7 | 4.7 ± 1.2 | 17.0 ± 2.3 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 15.1 ± 1.0 | 1.7 ± 0.1 |

| 11 | 8/6/2021 | 76.7 ± 1.0 | 8.9 ± 1.1 | 37.4 ± 1.3 | 9.7 ± 0.2 | 90.4 ± 0.2 | 10.1 ± 2.0 | 13.0 ± 0.3 | 8.9 ± 0.2 | 10.1 ± 0.0 | 1.2 ± 1.3 | 0.3 ± 0.1 |

| 12 | 12/10/2021 | 79.2 ± 0.6 | 16.1 ± 1.4 | 29.5 ± 1.1 | 10.5 ± 0.2 | 89.5 ± 0.2 | 10.1 ± 1.8 | 8.3 ± 0.9 | 7.3 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 12.7 ± 1.2 | 2.2 ± 0.3 |

| 13 | 2/11/2021 | 79.1 ± 0.5 | 10.9 ± 1.5 | 36.5 ± 1.2 | 6.0 ± 0.3 | 94.0 ± 0.3 | 14.1 ± 1.6 | 9.5 ± 1.2 | 7.3 ± 0.9 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 11.7 ± 0.7 | 2.2 ± 0.2 |

| 14 | 23/11/2021 | 76.0 ± 0.6 | 13.4 ± 0.2 | 29.4 ± 1.1 | 9.1 ± 2.2 | 90.9 ± 2.2 | 14.4 ± 2.7 | 2.3 ± 0.9 | 10.3 ± 0.9 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 19.4 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 0.3 |

| 15 | 7/12/2021 | 78.4 ± 0.3 | 12.0 ± 1.3 | 30.8 ± 2.5 | 11.5 ± 0.3 | 88.5 ± 0.3 | 12.7 ± 5.8 | 9.3 ± 1.7 | 7.1 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 12.4 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.1 |

| 16 | 22/02/2022 | 76.1 ± 0.4 | 5.6 ± 2.0 | 36.0 ± 1.7 | 9.6 ± 0.9 | 90.4 ± 0.9 | 13.6 ± 1.5 | 19.3 ± 2.4 | 11.1 ± 1.0 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 11.2 ± 1.8 | 2.1 ± 0.1 |

| 17 | 8/3/2022 | 77.3 ± 0.3 | 8.9 ± 0.8 | 38.6 ± 3.0 | 8.8 ± 0.7 | 91.2 ± 0.7 | 9.2 ± 2.5 | 12.9 ± 4.4 | 7.8 ± 1.0 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 10.0 ± 1.2 | 1.0 ± 0.0 |

| 18 | 22/03/2022 | 72.3 ± 0.4 | 10.0 ± 1.1 | 42.4 ± 0.5 | 9.6 ± 0.2 | 90.4 ± 0.2 | 12.7 ± 1.0 | 15.0 ± 1.5 | 8.0 ± 0.8 | 1.1 ± 0.0 | 9.0 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.0 |

| 19 | 5/4/2022 | 77.1 ± 0.4 | 6.9 ± 1.3 | 38.2 ± 1.0 | 8.4 ± 0.6 | 91.6 ± 0.6 | 9.8 ± 0.6 | 15.6 ± 0.1 | 11.9 ± 0.6 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 10.7 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 2.6 |

| 20 | 3/5/2022 | 74.7 ± 0.1 | 12.1 ± 2.5 | 32.2 ± 1.9 | 9.7 ± 0.4 | 90.3 ± 0.3 | 11.5 ± 5.0 | 10.3 ± 6.1 | 10.2 ± 1.0 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 10.5 ± 1.0 | 0.1 ± 0.5 |

| 21 | 18/05/2022 | 74.5 ± 0.2 | 8.1 ± 0.7 | 29.5 ± 2.0 | 4.6 ± 0.6 | 95.4 ± 0.6 | 15.5 ± 0.3 | 9.9 ± 1.9 | 5.6 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 17.8 ± 2.7 | 0.1 ± 0.6 |

| 22 | 1/6/2022 | 79.0 ± 0.2 | 8.9 ± 1.0 | 22.9 ± 0.9 | 8.9 ± 0.3 | 91.1 ± 0.3 | 15.2 ± 2.1 | 20.2 ± 1.0 | 9.8 ± 1.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 22.8 ± 1.2 | 0.1 ± 1.5 |

| 23 | 21/06/2022 | 75.8 ± 0.3 | 9.9 ± 1.4 | 29.3 ± 2.5 | 4.6 ± 1.5 | 95.4 ± 1.5 | 17.9 ± 0.1 | 8.1 ± 2.3 | 4.4 ± 0.9 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 21.4 ± 1.4 | 0.1 ± 0.6 |

| Successive Seasons | Cellulose | Starch | Free Glucose | Degrees of Freedom | t0.05 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020–2021 | 0.718 | 1.742 | 0.327 | 13 | 2.160 |

| Result | Not significant | Not significant | Not significant | ||

| 2021–2022 | 0.118 | 0.212 | 4.166 | 15 | 2.131 |

| Result | Not significant | Not significant | Significant |

| Successive Seasons | Cellulose | Starch | Free Glucose | Degrees of Freedom | t0.05 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winter–Spring | 0.122 | 0.070 | 0.661 | 13 | 2.160 |

| Result | Not significant | Not significant | Not significant | ||

| Spring–Summer | 0.080 | 0.131 | 1.560 | 8 | 2.306 |

| Result | Not significant | Not significant | Not significant | ||

| Summer–Autumn | 0.061 | 0.141 | 7.413 | 6 | 2.447 |

| Result | Not significant | Not significant | Significant | ||

| Autumn–Winter | 0.277 | 0.508 | 2.212 | 11 | 2.201 |

| Result | Not significant | Not significant | Significant |

| Experiments | Spirizyme (μL/g Starch) | NS87014 (μL/g Cell.) | S.cerevisiae (% w/w) | Ethanol (g/L) | Glucose (g/L) | TOC (g/L) | Solids Degradation (%) | Ethanol Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 | 100 | 1% | 13.0 ± 0.00 | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 16.1 ± 0.3 | 49.6 ± 0.2 | 78.4 ± 0.4 |

| 2 | 20 | 250 | 1% | 14.0 ± 0.00 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 16.3 ± 0.4 | 50.6 ± 1.2 | 84.6 ± 0.1 |

| 3 | 60 | 100 | 1% | 13.0 ± 0.00 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 16.3 ± 0.5 | 49.6 ± 0.5 | 78.2 ± 0.7 |

| 4 | 60 | 250 | 1% | 14.5 ± 0.71 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 17.0 ± 0.3 | 51.7 ± 0.9 | 87.7 ± 4.3 |

| 5 | 20 | 100 | 3% | 12.0 ± 0.00 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 16.1 ± 0.4 | 45.5 ± 1.3 | 72.6 ± 0.0 |

| 6 | 20 | 250 | 3% | 13.0 ± 0.00 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 16.8 ± 0.1 | 44.7 ± 3.2 | 78.7 ± 0.0 |

| 7 | 60 | 100 | 3% | 13.0 ± 0.00 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 16.8 ± 0.2 | 46.1 ± 0.9 | 78.2 ± 0.0 |

| 8 | 60 | 250 | 3% | 13.5 ± 0.00 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 17.2 ± 0.2 | 46.8 ± 0.6 | 81.6 ± 0.6 |

| 9 | 40 | 175 | 2% | 13.5 ± 1.00 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 16.9 ± 0.7 | 47.4 ± 1.7 | 81.7 ± 6.1 |

| Trial | Solid Loading (%) | Ethanol (g/L) | Glucose (g/L) | Ethanol Yield (%) | Cellulose Degradation (%) | Starch Degradation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | 12.3 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 83.4 ± 0.4 | 56.2 ± 1.2 | 97.8 ± 1.1 |

| 2 | 15 | 19.3 ± 1.1 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 82.5 ± 0.3 | 54.5 ± 1.1 | 97.1 ± 0.9 |

| 3 | 20 | 28.8 ± 1.2 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 86.5 ± 0.3 | 64.1 ± 1.0 | 96.5 ± 0.8 |

| 4 | 25 | 37.5 ± 2.0 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 84.6 ± 0.3 | 71.4 ± 1.4 | 97.1 ± 0.2 |

| 5 | 30 | 30.0 ± 2.2 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 52.7 ± 0.8 | 63.1 ± 1.1 | 96.6 ± 0.4 |

| Degradation Efficiency (%) | Trial | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | Mean Value | |

| Total Solids | 46.3 | 46.4 | 63.9 | 70.2 | 68.0 | 64.3 | 68.5 | 65.7 | 67.7 | 68.8 | 65.5 | 65.3 | 68.1 | 64.5 | 63.8 ± 7.6 |

| Starch | 89.5 | 95.4 | 92.4 | 95.2 | 95.7 | 95.9 | 90.8 | 83.2 | 96.4 | 93.4 | 96.1 | 96.4 | 95.8 | 96.9 | 93.8 ± 3.8 |

| Cellulose | 73.6 | 38.8 | 74.3 | 88.3 | 78.8 | 72.5 | 82.3 | 71.1 | 68.9 | 75.6 | 76.0 | 77.5 | 80.3 | 81.7 | 74.3 ± 11.4 |

| Oils | 62.8 | 56.1 | 57.4 | 70.2 | 74.6 | 9.2 | 70.7 | 84.9 | 37.0 | 42.9 | 24.8 | 76.5 | 64.1 | 68.5 | 57.1 ± 21.4 |

| WS | 52.6 | 53.5 | 68.0 | 70.2 | 68.0 | 64.3 | 68.5 | 65.7 | 78.8 | 78.3 | 74.3 | 69.6 | 79.2 | 73.3 | 68.9 ± 8.2 |

| Hemicellulose | 12.2 | 22.9 | 79.3 | 62.6 | 37.1 | 77.1 | 67.3 | 45.0 | 55.7 | 68.8 | 70.0 | 64.1 | 46.6 | 54.4 | 54.5 ± 19.9 |

| ASL | 27.3 | 1.2 | 39.2 | 83.0 | 42.1 | 27.6 | 44.7 | 55.8 | 67.4 | 51.3 | 34.9 | 0.8 | 24.9 | 64.1 | 40.3 ± 23.5 |

| AIR | 28.3 | 0.2 | 15.2 | 57.2 | 62.0 | 29.6 | 46.4 | 57.1 | 42.3 | 5.2 | 42.7 | 66.4 | 44.7 | 33.9 | 38.0 ± 20.5 |

| Property | Measurement Unit | Method | Limit | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density at 15 °C | g/mL | EN ISO 12185 | 0.7951 | |

| Methanol | % w/w | EN 15721 | <1.0 | 0.01 |

| Propan-1-ol | % w/w | EN 15721 | 0.15 | |

| Butan-1-ol | % w/w | EN 15721 | 0.01 | |

| Butan-2-ol | % w/w | EN 15721 | 0.27 | |

| 2-Methylpropan-1-ol | % w/w | EN 15721 | 0.00 | |

| 2-Methylbutan-1-ol | % w/w | EN 15721 | 0.15 | |

| 3-Methylbutan-1-ol | % w/w | EN 15721 | 0.00 | |

| Higher saturated (C3–C5) mono alcohol | % w/w | EN 15721 | <2.0 | 0.57 |

| Ethanol and higher saturated alcohol | % w/w | EN 15721 | >98.7 | 99.91 |

| Water | % w/w | EN 15489 | <0.3 | 0.450 |

| Total acidity (expressed as acetic acid) | % w/w | EN 15491 | <0.007 | 0.001 |

| Electrical Conductivity at 25 °C | uS/cm | EN 15938 | <2.5 | 0.20 |

| Appearance | - | EN 15769 | Clear | Clear |

| Color | - | EN 15769 | Colorless | Colorless |

| Inorganic chloride | mg/kg | EN 15484 | <6.0 | 0.1 |

| Sulfate | mg/kg | EN 15492 | <4.0 | 1.0 |

| Involatile material | mg/100 mL | EN 15691 | <10 | 1 |

| Total Sulphur | ppm-w | ASTM D-5453 | <10.0 | 2.1 |

| Time (h) | Conditions | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | Stirring Rate (%) | Stirring Time (min/h) | |

| 0–8 | 35 | 35 | 40 |

| 9–24 | 35 | 20 | 25 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsafara, P.; Passadis, K.; Christianides, D.; Chatziangelakis, E.; Bousoulas, I.; Malamis, D.; Mai, S.; Barampouti, E.M.; Moustakas, K. Advanced Bioethanol Production from Source-Separated Bio-waste in Pilot Scale. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12127. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912127

Tsafara P, Passadis K, Christianides D, Chatziangelakis E, Bousoulas I, Malamis D, Mai S, Barampouti EM, Moustakas K. Advanced Bioethanol Production from Source-Separated Bio-waste in Pilot Scale. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):12127. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912127

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsafara, Panagiota, Konstantinos Passadis, Diogenis Christianides, Emmanouil Chatziangelakis, Ioannis Bousoulas, Dimitris Malamis, Sofia Mai, Elli Maria Barampouti, and Konstantinos Moustakas. 2022. "Advanced Bioethanol Production from Source-Separated Bio-waste in Pilot Scale" Sustainability 14, no. 19: 12127. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912127

APA StyleTsafara, P., Passadis, K., Christianides, D., Chatziangelakis, E., Bousoulas, I., Malamis, D., Mai, S., Barampouti, E. M., & Moustakas, K. (2022). Advanced Bioethanol Production from Source-Separated Bio-waste in Pilot Scale. Sustainability, 14(19), 12127. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912127