Does Public Participation Matter to Planning? Urban Sculpture Reception in the Context of Elite-Led Planning in Shanghai

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Conceptual Framework: The Cultural Elite-Led Approach to Public Participation and the Factors That Influence Art Reception

2.1. Elite-Dominated Public Participation in China’s Cultural Development Projects

2.2. Hypothesizing the Impact of Locality on Public Art Reception

2.2.1. Prominent Public Venues in City Centers

2.2.2. Neighborhoods

2.3. The Perspective of “Cultural Sustainability”

3. Research Methods

3.1. Research Design and Sampling Method

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Public Participation in Urban Sculpture Planning

4.1. The Background: Urban Sculpture Planning in Shanghai’s Urban Development

4.2. The Cultural Elite-Led Public Participation in Shanghai’s Urban Sculpture Planning

5. Results and Discussions: The Impact of Locality on Public Art Reception within the Elite-Led Context

5.1. Reverence towards Flagship Art Projects in Prominent Public Localities

5.2. Contested Spaces of Art in Neighborhoods

5.3. The Construction of Informal Urban Sculpture Sites in Daily Lives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Churchman, A. Public Participation around The World: Introduction to the Special Theme Issue. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2012, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Skeffington, A. Report of the Committee on Public Participation in Planning; HMSO: London, UK, 1969.

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowndes, V.; Pratchett, L.; Stoker, G. Trends in Public Participation: Part 1–Local Government Perspectives. Public Adm. 2001, 79, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilvers, J. Deliberating Competence. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2008, 3, 155–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, V.; Robert, B.P. The Companion to Development Studies; Hodder Education: London, UK, 2008; pp. 115–119. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M.S. Stakeholder Participation for Environmental Management: A Literature Review. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 2417–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, A.A. Three-Dimensional View of Public Participation in Scottish Land Use Planning. Plan. Theory 2010, 9, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyles, W.; White, S.S. Who Cares? Arnstein’s Ladder, The Emotional Paradox of Public Engagement, and (Re) imagining Planning as Caring. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2019, 3, 287–300, 298, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naess, P. Urban Planning and Sustainable Development. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2001, 9, 503–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dola, K.; Mijan, D. Public Participation in Planning for Sustainable Development: Operational Questions and Issues. Int. J. Sustain. Trop. Des. Res. Pract. 2006, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Teriman, S. Rethinking Sustainable Urban Development: Towards an Integrated Planning and Development Process. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 12, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G. Cultural Planning: An Urban Renaissance? Routledge: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dreeszen, C. Cultural Planning Handbook: A Guide for Community Leaders; Americans for the Arts: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Grodach, C. Beyond Bilbao: Rethinking Flagship Cultural Development and Planning in Three California Cities. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2010, 29, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstein, C. Cultural Development and City Neighborhoods; Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Grodach, C.; Loukaitou-Sideris, A. Cultural Development Strategies and Urban Revitalization: A Survey of US Cities. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2007, 13, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, D.R.; Michael, E.P. Environmental Psychology: Mapping Landscape Meanings for Ecosystem Management. In Human Dimensions in Assessment, Policy, and Management; Herry, K.C., Jason, C.B., Eds.; Sagamore Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 1999; pp. 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- Jordaan, T.; Puren, K. “We Love This Place”: Place Attachment and Community Engagement in Urban Conservation Planning. Chall. Mod. Technol. 2012, 3, 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F. Re-orientation of The City Plan: Strategic Planning and Design Competition in China. Geoforum 2007, 38, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, A.G.O.; Wu, F. The Transformation of the Urban Planning System in China from a Centrally-planned to Transitional Economy. Prog. Plan. 1999, 51, 167–252. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J. Producing Chinese Urban Landscapes of Public Art: The Urban Sculpture Scene in Shanghai. China Q. 2019, 239, 775–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B. Participatory and Deliberative Institutions in China. In The Search for Deliberative Democracy in China; Leib, E., He, B., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 175–196. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, J.H. Societal Challenges to Governance in China: Mapping the Major Trends. 2004. Available online: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/mapping-chinas-global-governance-ambitions/ (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Beyea, W. Place Making through Participatory Planning. In Handbook of Research on Urban Informatics: The Practice and Promise of the Real-Time City; Marcus, F., Ed.; Information Science Reference: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, B.; Cai, Y. Interests and Political Participation in Urban China: The Case of Residents’ Committee Elections. China Rev. 2015, 15, 95–116. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, J. Transitional Urban Community Organizations; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q. Building Urban China with Community Participation: Linking Well-Being and Empowerment; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, UK, 2004; unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Fang, K. Is History Repeating Itself? From Urban Renewal in the United States to Inner-city Redevelopment in China. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2004, 23, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. The Global and Local Dimensions of Place-making: Remaking Shanghai as a World City. Urban Stud. 2000, 37, 1359–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W. Study of Public Participation in Land-use Planning. China Land Sci. 2003, 17, 51–56. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ng, M.K.; Xu, J. Development Control in Post-reform China: The Case of Liuhua Lake Park, Guangzhou. Cities 2000, 17, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X. Forward to the Past: Historical Preservation in Globalizing Shanghai. City Community 2008, 7, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wu, F. China’s Emerging Neoliberal Urbanism: Perspectives from Urban Redevelopment. Antipode 2009, 41, 282–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J. “Creative Industry Clusters” and The “Entrepreneurial City” of Shanghai. Urban Stud. 2011, 48, 3561–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J. The “Entrepreneurial State” in “Creative Industry Cluster” Development in Shanghai. J. Urban Aff. 2010, 32, 143–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Sun, M. Artistic Urbanization: Creative Industries and Creative Control in Beijing. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2012, 36, 504–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. The Geographic Political Economy of Art District Formation in China: The Case of Songzhuang. Geoforum 2019, 106, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S.J. Known by The Network: The Emergence of Location-based Mobile Commerce. In Advances in Mobile Commerce Technologies; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2003; pp. 171–189. [Google Scholar]

- Albrechts, L. Strategic (spatial) Planning Reexamined. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2004, 31, 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrechts, L. In Pursuit of New Approaches to Strategic Spatial Planning: A European Perspective. Int. Plan. Stud. 2001, 6, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tippett, J.; Searle, B.; Pahl-Wostl, C.; Rees, Y. Social Learning in Public Participation in River basin Management—Early Findings from Harmoni COP European Case Studies. Environ. Sci. Policy 2005, 8, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faludi, A. The Performance of Spatial Planning. Plan. Pract. Res. 2000, 15, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, A. Putting the Public back into Governance: The Challenges of Citizen Participation and Its Future. Public Adm. Rev. 2015, 75, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, B.; Kothari, U. The Case for Participation as Tranny. In Participation: The New Tyranny; Cooke, B., Uma, K., Eds.; Zed Books: London, UK, 2001; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Aitken, M. Wind Power and Community Benefits: Challenges and Opportunities. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 6066–6075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, G.; Frewer, L.J. Public Participation Methods: A Framework for Evaluation. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2000, 25, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacione, M. The Power of Public Participation in Local Planning in Scotland: The Case of Conflict over Residential Development in the Metropolitan Green Belt. GeoJournal 2014, 79, 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pateman, C. Participation and Democratic Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Kweit, R.W.; Kweit, M.G. Implementing Citizen Participation in a Bureaucratic Society: A Contingency Approach; Praeger Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Townshend, T.; Pendlebury, J. Public Participation in the Conservation of Historic Areas: Case-studies from North-east England. J. Urban Des. 1999, 4, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redaelli, E. Cultural Planning in the United States: Toward Authentic Participation using GIS. Urban Aff. Rev. 2012, 48, 642–669, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendlebury, J. The conservation of historic areas in the UK: A case study of “Grainger Town”, Newcastle upon Tyne. Cities 1999, 16, 423–433, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, D. A Comparison of the Model Cities Program of St. Louis and Kansas City, Missouri. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- García, I. Community Participation as a Tool for Conservation Planning and Historic Preservation: The Case of “Community as A Campus” (CAAC). J. Hous. Built Environ. 2018, 33, 519–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J. Toward a New Concept of the “Cultural Elite State”: Cultural Capital and The Urban Sculpture Planning Authority in Elite Coalition in Shanghai. J. Urban Aff. 2017, 39, 506–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J. Rethinking the growth machine logic in cultural development: Urban sculpture planning in Shanghai. China Inf. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrower, M.L. Modeling Supply and Demand for Residential Real Estate: Testing Economic Theory at the Metropolitan Level. Doctoral Dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield, A. Citizenship and Community: Civic Republicanism and the Modern World; Routledge: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Polsby, N.W. Community Power and Political Theory; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1963; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, R.A. Who Governs? Power and Democracy in an American City; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Kweit, R.W.; Kweit, M.G. People and Politics in Urban America; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wahlström, M.H. Planning Cities4People: A Body and Soul Analysis of Urban Neighbourhoods. Public Manag. Rev. 2020, 22, 687–700, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. The Image of The City; MIT Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley, I. Responsive Environments: A Manual for Designers; Architectural Press: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, J. Reflections on Place and Place-making in the Cities of China. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2007, 31, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, A. Culture Sits in Places: Reflections on Globalism and Subaltern Strategies of Localization. Political Geogr. 2001, 20, 139–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeShazo, J.L.; Smith, Z.A. Administering public art programs in Arizona’s cities and towns: Development, operation, and promotion. J. Arts Manag. Law Soc. 2014, 44, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M. A Game of Appearance: Public Art and Urban Development—Complicity or Sustainability. In The Entrepreneurial City: Geographies of Politics, Regime and Representation; Amer, A., Ed.; John Wiley and Son Limited: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 203–204. [Google Scholar]

- Lacy, S. Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art; Bay Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J. Contextualizing Public Art Production in China: The Urban Sculpture Planning System in Shanghai. Geoforum 2017, 82, 89–101, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, P.C. Out of Order: The Public Art Machine. Artforum 1988, 27, 92–97. [Google Scholar]

- Day, D. Citizen Participation in the Planning Process: An Essentially Contested Concept? J. Plan. Lit. 1997, 11, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stivers, C. The Public Agency as Polis: Active Citizenship in the Administrative State. Adm. Soc. 1990, 22, 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, J. Planning in The Public Domain: From Knowledge to Action; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- McNair, R.H.; Caldwell, R.; Pollane, L. Citizen Participants in Public Bureaucracies: Foul Weather Friends. Adm. Soc. 1983, 14, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshansky, H.M.; Abbe, K.F.; Robert, K. Place-identity: Physical World Socialization of the Self. J. Environ. Psychol. 1983, 3, 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashmore, R.D.; Kay, D.; Tracy, M.-V. An Organizing Framework for Collective Identity: Articulation and Significance of Multidimensionality. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 130, 80–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Masso, A.; Dixon, J.; Durrheim, K. Place Attachment as Discursive Practice. In Place Attachment: Advances in Theory, Methods and Applications; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Dlamini, S.; Tesfamichael, S.G.; Mokhele, T. A Review of Place Identity Studies in Post-apartheid South Africa. South Afr. J. Psychol. 2021, 51, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lwoga, N.B.; Anderson, W.; Andersson, T.D.T. Influence of Participation, Trust and Perceptions on Residents’ Support for Conservation of Built Heritage in Zanzibar Stone Town, Tanzania. Ethiop. J. Environ. Stud. Manag. 2017, 10, 1179–1192. [Google Scholar]

- Castree, N. From Neoliberalism to Neoliberalisation: Consolations, Confusions, and Necessary Illusions. Environ. Plan. A 2006, 38, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, S. Debated Territory: Toward a Critical Language for Public Art. In Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art; Bay Press: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 1995; pp. 171–185. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, J. Pollock, V.; Paddison, R. Just Art for a Just City: Public Art and Social Inclusion in Urban Regeneration. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 1001–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcolm, M. Art Space and the City–Public Art and Urban Features; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wildavsky, A.B. Speaking Truth to Power; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- May, P.J. Reconsidering Policy Design: Policies and publics. J. Public Policy 1991, 11, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savini, F. The Endowment of Community Participation: Institutional Settings in Two Urban Regeneration Projects. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2011, 35, 949–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedman, R.C. Toward a Social Psychology of Place: Predicting Behavior from Place-based Cognitions, Attitude, and Identity. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A. Slumdog Cities: Rethinking Subaltern Urbanism. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2011, 35, 223–238, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soini, K.; Birkeland, I. Exploring the Scientific Discourse on Cultural Sustainability. Geoforum 2014, 51, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen, T.H. A Critique of the UNESCO Concept of Culture. In Culture and Rights, Anthropological Perspectives; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; pp. 127–148. [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury, N.; Gillette, E. Culture as a Key Dimension of Sustainability: Exploring Concepts, Themes, and Models; Creative City Network of Canada: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Macbeth, J. Towards an Ethics Platform for Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 962–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Der Pahlen, M.C.; Grinspoon, E. Promoting Traditional Uses of Medicinal Plants as efforts to Achieve Cultural and Ecological Sustainability. J. Sustain. For. 2002, 15, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, P.; Aberdeen, L.; Schuler, S. Tourism Impacts on an Australian Indigenous Community: A Djabugay Case Study. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, T.; Stronza, A. Dwelling’ with Ecotourism in the Peruvian Amazon: Cultural Relationships in Local—Global Spaces. Tour. Stud. 2008, 8, 313–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsey, E.R.; Steeves, H.L.; Porras, L.E. Advertising Ecotourism on the Internet: Commodifying Environment and Culture. N. Media Soc. 2004, 6, 753–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radović, D. Towards Culturally Responsive and Responsible Teaching of Urban Design. Urban Des. Int. 2004, 9, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, K.J.; Brudney, J.L.; Bohte, J. Applied Statistics for Public and Nonprofit Administration; Cengage Learning: Stamford, CT, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Municipal Urban Sculpture Committee Office (MUSCO). A Survey of Urban Sculpture Venues. 2017; (unpublished official document). (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zebracki, M. Beyond Public Artopia: Public Art as Perceived by Its Publics. GeoJournal 2013, 78, 303–317, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeile, P.; Resch, B.; Exner, J.P.; Sagl, G. Urban Emotions: Benefits and Risks in using Human Sensory Assessment for the Extraction of Contextual Emotion Information in Urban Planning. In Planning Support Systems and Smart Cities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 209–225. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J. Structuring Artistic Creativity for The Production of a “Creative City”: Urban Sculpture Planning in Shanghai. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2021, 45, 795–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chief Officer in the MUSCO; Shanghai, China. Personal communication, 7 February 2019.

- Experts in the Arts Committee; Shanghai, China. Personal communication, 12 December 2018.

- Shanghai People’s Government [SPG]. Shanghai Urban Sculpture Master Plan [Shanghai Chengshi Diaosu Zongti Guihua]. 2004; (unpublished official document). [Google Scholar]

- Chief Sculpture Officer at MUSCO; Shanghai, China. Personal communication, 17 May 2018.

- The Maintenance Manager of the Jing’an Sculpture Park; Shanghai, China. Personal communication, 22 July 2018.

- The Chief Sculpture Officer in Jing’an District and Huangpu; Shanghai, China. Personal communication. 23 May and 10 December 2018.

- The Vice Chief Manager of the Nanjing Road Investment Corporation; Shanghai, China. Personal communication, 13 January 2019.

- The Chief Sculpture Officer in Changning District; Shanghai, China. Personal communication, 23 May 2018.

- Questionnaire survey at the May 30th Sculpture. 2 March 2019.

- Residents in the Zhangjiaxiang Residential District; Shanghai, China. Personal communication, 25 May 2019.

- Questionnaire survey at the Zhangjiaxiang Neighborhood. 18 June 2019.

- Chen, Q.; Jiang, C.M. Amenities in the Zhangjiaxiang Residential District: Analysis of the Current Condition, 2003. Student Research Report at Fudan University. (unpublished document).

- Ling, F.F.; Chief Executive Officer of the Yuanming Group Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China. Personal communication, 20 August 2018.

- Site visit at the Lingshi Park. 30 March 2019.

- The Ronghua Residents’ Committee at the Gubei New Town; Shanghai, China. Personal communication, 3 August 2018.

- Site Visit at the Gubei New Town. 8 June 2018.

- Residents at the Zhangjiaxiang Residential District; Shanghai, China. Personal communication, 24 February 2019.

- Site Visit at the Taopu Neighborhood. 20 February 2019.

- Site Visit at the Jiuzi Park. 2 March 2019.

| Sculpture Venues | Venue Type | Number of Questionnaires Distributed | Valid Questionnaires | Date of Survey |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gubei New Town | High-end neighborhood | 30 | 29 | 8 June 2018 |

| Zhangjiaxiang Neighborhood | Working-class neighborhood (WN) | 20 | 20 | 18 June 2018 |

| Chenan Neighborhood | WN | 30 | 30 | 28 June 2018 |

| Jing’an Sculpture Park | Flagship-art project (FP)—contemporary art venue (CAV) | 40 | 36 | 28 June 2018 |

| Shanghai International Sculpture Centre | FP—CAV | 30 | 30 | 11 October 2018 |

| Bundbull | FP—iconic landmark (IL) | 15 | 15 | 26 March 2019 |

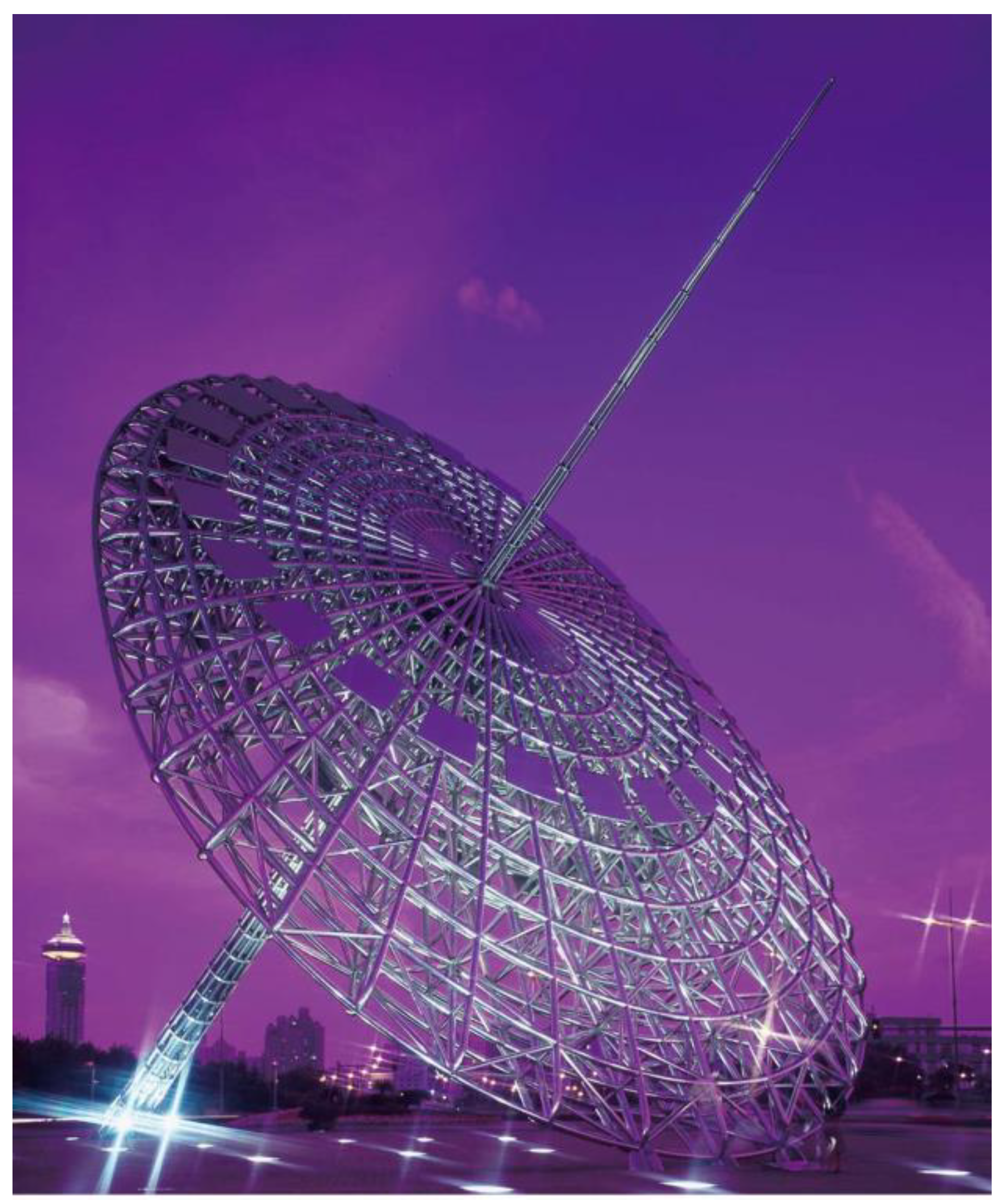

| Huamu Avenue Pudong | FP—IL | 30 | 30 | 18 June 2018 |

| 30 May Sculpture | FP—revolutionary monument | 15 | 14 | 2 March 2019 |

| Duolun Road Sculpture Walk | FP—historical monument | 30 | 26 | 28 October 2018 |

| Telephone Lady | Democratic monument | 15 | 14 | 1 March 2019 |

| Total/Rate | 255 | 244 (95.7%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, J.; Zheng, X. Does Public Participation Matter to Planning? Urban Sculpture Reception in the Context of Elite-Led Planning in Shanghai. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12179. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912179

Zheng J, Zheng X. Does Public Participation Matter to Planning? Urban Sculpture Reception in the Context of Elite-Led Planning in Shanghai. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):12179. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912179

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Jane, and Xiaohua Zheng. 2022. "Does Public Participation Matter to Planning? Urban Sculpture Reception in the Context of Elite-Led Planning in Shanghai" Sustainability 14, no. 19: 12179. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912179