The Relationship between Figureheads and Managerial Leaders in the Private University Sector: A Decentralised, Competency-Based Leadership Model for Sustainable Higher Education

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Research Gap and Scope: Objective and Questions

- How does the relationship between a “figurehead” and the managerial leadership team work?

- How does this relationship influence business success?

- Do the principles in education or the goal of business drive success?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Genesis of “Figurehead” Leadership: Implications for Education

2.2. Transformations in Educational Leadership

2.3. Transformation of University Philosophy: Challenges for Private University Leadership

2.4. International Comparative Significance

3. Research Context

3.1. Private University Sector: Nature of Ownership

3.2. Governance and Leadership

4. Research Design

4.1. Methodological Approach: Justification for the Qualitative Method

4.2. Domains’ (Instrument) Development: Secondary Data Collection, Analysis, and Reliability

4.3. Sampling and Triangulation for Interviews: Primary Data

4.4. Primary Data Collection, Analysis: Confidentiality and Coding

5. Findings and Discussions

5.1. Relationship between Figurehead and Managerial Leadership

5.2. Dynamic Changes in Figurehead Leadership: Management Crisis

5.3. Leadership and Business Success

5.4. Factors Influencing Success: Education Philosophy or Business Motive

5.5. Diversity in Revenue Collection and Leadership Dynamics: A Way Forward

6. Implications, Further Research, and Limitations

6.1. Theoretical Implication and Its Practice

6.2. Decentralised, Competency-Based Leadership Model: Sustainable Higher Education

6.3. Further Research and Limitations

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morrison, A.J. Developing a global leadership model. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2000, 39, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, T. From Management to Leadership: Semantic or Meaningful Change? Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2008, 36, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, C.; Lee, J.S.K.; Lan, L.L. Why Women Say No to Corporate Boards and What Can Be Done: “Ornamental Directors” in Asia. J. Manag. Inq. 2014, 24, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.; Lo, W. Running Universities as Enterprises: University Governance Changes in Hong Kong. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 2007, 27, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G.M. Quality assurance for private universities in Bangladesh: A quest for specialised institutional governance, management and regulatory mechanism. Int. J. Comp. Educ. Dev. 2019, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G.M.; Parvin, M.; Roslan, S. Growth of private university business following “oligopoly” and “SME” approaches: An impact on the concept of university and on society. Soc. Bus. Rev. 2021, 16, 306–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altbach, P. Higher education and the WTO: Globalization run amok. Int. High. Educ. 2001, 23, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, S.; Ilyas, M.; Hameed, A. Student satisfaction and impact of leadership in private universities. TQM J. 2013, 25, 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Hee, T.F.; Piaw, C.Y. A Qualitative Analysis of the Leadership Style of a Vice-Chancellor in a Private University in Malaysia. Sage Open 2015, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijazi, S.; Kasim, A.F.; Daud, Y. Leadership Styles and Their Relationship with the Private University Employees’ Job Satisfaction in United Arab Emirates. J. Public Adm. Gov. 2016, 6, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhana, S.; Udin, U.; Suharnomo, S.; Ud, F.M. Transformational Leadership and Innovative Behavior: The Mediating Role of Knowledge Sharing in Indonesian Private University. Int. J. High. Educ. 2019, 8, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, B.; Ayoubi, R.M. Leadership styles at Syrian higher education: What matters for organizational learning at public and private universities? Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2015, 29, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G.M.; Forhad, A.R.; Ismi, I.A. Can education as an ‘International Commodity’ be the backbone or cane of a nation in the era of fourth industrial revolution? A comparative study. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 159, 120184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shammari, M.; Waleed, R. Entrepreneurial intentions of private university students in the kingdom of Bahrain. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2018, 10, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, M.T. Student intimidation, no pay and hunger strikes: The challenges facing Heads of Department in Bangladesh colleges. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2020, 42, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, M.; James, C.; Fertig, M. The difference between educational management and educational leadership and the importance of educational responsibility. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2019, 47, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G.M.; Roslan, S.; Al-Amin, A.Q. Does GATS’ Influence on Private University Sector’s Growth Ensure ESD or Develop City ‘Sustainability Crisis’—Policy Framework to Respond COP21. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, M. Solo and distributed leadership: Definitions and dilemmas. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2012, 40, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottery, M. The Challenges of Educational Leadership; Paul Chapman: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gunter, H. Labels and labelling in the field of educational leadership. Discourse-Stud. Cult. Politics Educ. 2004, 25, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, P. Authenticity in the bureau-enterprise culture: The struggles for authentic meaning. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2007, 35, 295–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, T.; Glover, D. School leadership models: What do we know? Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2014, 34, 553–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, T. Moving the school forward: Problems reported by novice and experienced principals during a succession process in Chile. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2018, 62, 201–208. [Google Scholar]

- Rosser, V.J. A national study on midlevel leaders in higher education: The unsung professionals in the academy. High. Educ. 2004, 48, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; Spillane, J. Distributed leadership through the looking glass. Manag. Educ. 2008, 22, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ameijde, J.D.J.; Nelson, P.C.; Billsberry, J.; Meurs, M.V. Improving leadership in Higher Education institutions: A distributed perspective. High. Educ. 2009, 58, 763–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, T. Leadership and context: Why one-size does not fit all. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2017, 46, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, J.H. The Idea of University Defined and Illustrated; Oxford University: London, UK, 1852. [Google Scholar]

- May, T.; Perry, B. The role of universities in setting the knowledge economy Agenda. J. Int. Aff. 2018, 72, 182–184. [Google Scholar]

- McKelvey, M.; Buenstorf, G.; Broström, A. The knowledge economy, innovation and the new challenges to universities. Innovation 2018, 20, 84–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G.M.; Al-Amin, A.Q.; Forhad, M.A.R.; Mubarak, M.S. Does the private university sector exploit sustainable residential life in the name of supporting the fourth industrial revolution? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 159, 120200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, J. Institutional ownership and governance. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2020, 36, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Effective leadership in higher education: A literature review. Stud. High. Educ. 2008, 32, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altbach, P.G. Twisted roots: The Western impact on Asian higher education. In From Dependence to Autonomy; Altbach, P.G., Selvaratnam, V., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazelkorn, E.; Gibson, A. Global science, national research, and the question of university rankings. Palgrave Commun. 2017, 3, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazelkorn, E.; Gibson, A. Public goods and public policy: What is public good, and who and what decides? High. Educ. 2019, 78, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, W.; Bennion, A. The United Kingdom: Academic Retreat or Professional Renewal? In Changing Governance and Management in Higher Education; Locke, W., Cummings, W., Fisher, D., Eds.; The Changing Academy—The Changing Academic Profession in International Comparative Perspective; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 2, pp. 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, W.; Cummings, W.K.; Fisher, D. Comparative Perspectives: Emerging Findings and Further Investigations. In Changing Governance and Management in Higher Education; Locke, W., Cummings, W., Fisher, D., Eds.; The Changing Academy—The Changing Academic Profession in International Comparative Perspective; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 2, pp. 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazelkorn, E. Globalization and the Continuing Influence of Rankings—Positive and Perverse—On Higher Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zulfqar, A.; Valcke, M.; Devos, G.; Shahzad, A. Leadership and decision-making practices in public versus private universities in Pakistan. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2016, 17, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBrayer, J.S.; Jackson, T.; Pannell, S.S. Balance of Instructional and Managerial Tasks as it Relates to School Leaders’ Self-Efficacy. J. Sch. Leadersh. 2018, 28, 596–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J. Doing Your Research Project; Open University: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. Descriptive Statistics; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bolster, C.H. Revisiting a Statistical Shortcoming when Fitting the Langmuir Model to Sorption Data. J. Environ. Qual. 2008, 37, 1986–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G.M. Three parameters of urban K8 education during pre- and post-COVID 19 restrictions: Comparison of students of slums, tin-sheds, and flats in Bangladesh. Educ. Urban Soc. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, K.P.; Russo, C.J.; Dieterich, C.A.; Osborne, A.G.; Synder, N.D. Legal Issues in Special Education: Principles, Policies, and Practices; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, G.M. Does online provide sustainable HE or aggravate diploma disease? Evidence from Bangladesh—A comparison of conditions before and during COVID-19. Technol. Soc. 2022, 66, 101677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Carracedo, F.; Moreno-Pino, F.M.; Romero-Portillo, D.; Sureda, B. Education for Sustainable Development in Spanish University Education Degrees. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J.P. Distributed Leadership; Jossey-Bass: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, C.J. Summary and Recommendations for the Teaching of Religion in Public Schools; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Weisser, C.R. Defining sustainability in higher education: A rhetorical analysis. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2017, 18, 1076–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunter, H. Distributed Leadership: A Study in Knowledge Production. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2013, 41, 555–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G.M. Transforming the paradigm of public university leadership into a more political one in emerging nations—A case of Bangladesh. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, in press.

- Alam, G.M.; Asimiran, S.; Ismail, I.A.B.; Ahmad, N.A. The relationship between ornamental and managerial leader in private university sector: Who runs the show and makes a difference? Int. J. Educ. Reform. 2022, in press. [CrossRef]

| RQ | Primary Tool(s) | Auxiliary Tool(s) | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| How is the relationship between figurehead and managerial leadership established? | Document reviews | Interviews | Qualitative |

| How does this relationship influence business success? | Interviews | Document review | Qualitative |

| Does education philosophy or business motives drive success? | Interviews | Literature review, interpretation of the findings, and discussion of earlier research questions | Qualitative |

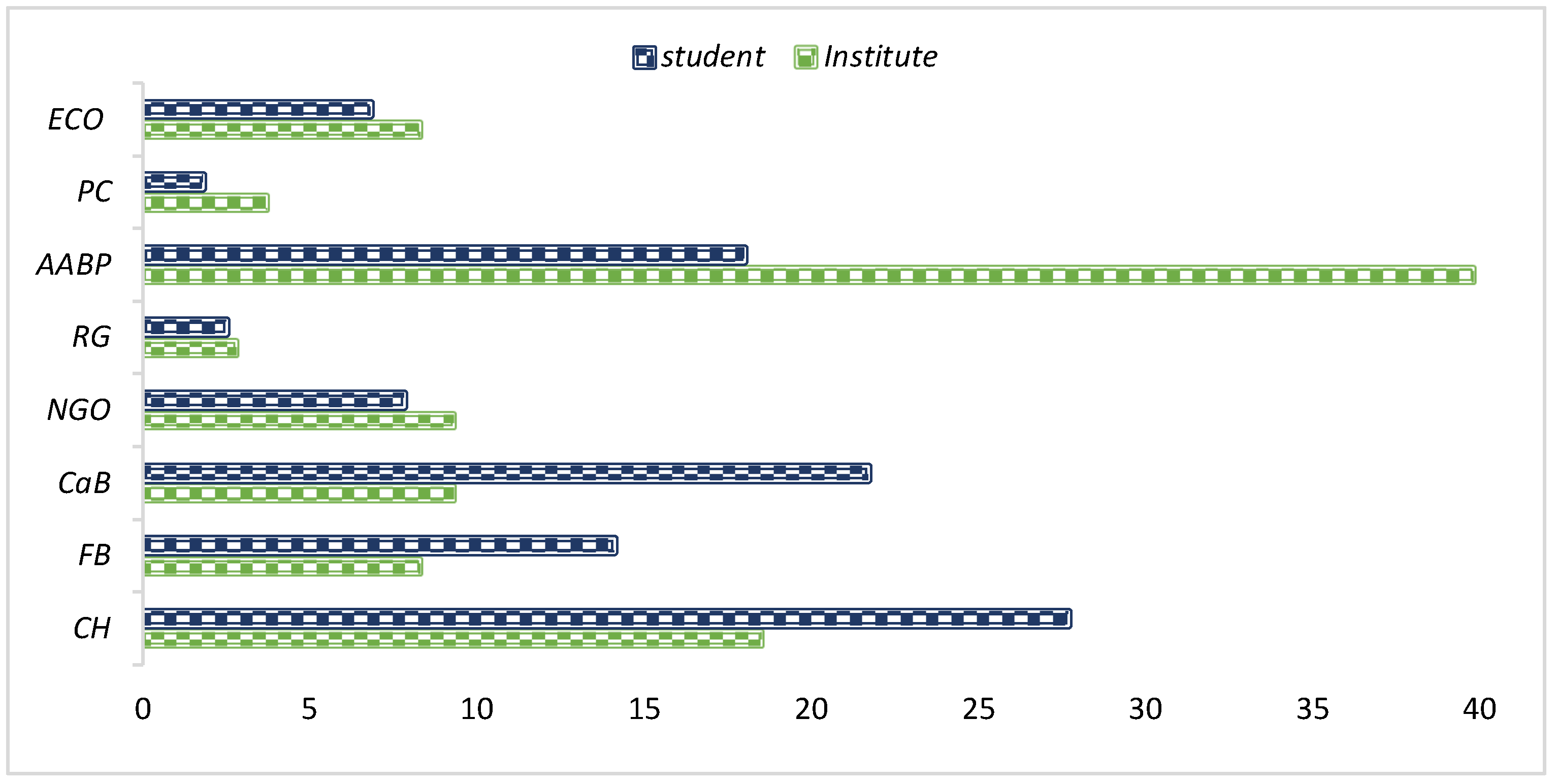

| Type of University Based on Ownership | University Number | BoT | Management | Academics | Students | Total Respondents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH | 3 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 18 |

| FB | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 12 |

| CaB | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 12 |

| NGO | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 12 |

| RG | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| AABP | 5 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 30 |

| PC | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| ECO | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 12 |

| Total | 18 | 18 | 18 | 36 | 36 | 108 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alam, G.M. The Relationship between Figureheads and Managerial Leaders in the Private University Sector: A Decentralised, Competency-Based Leadership Model for Sustainable Higher Education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12279. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912279

Alam GM. The Relationship between Figureheads and Managerial Leaders in the Private University Sector: A Decentralised, Competency-Based Leadership Model for Sustainable Higher Education. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):12279. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912279

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlam, Gazi Mahabubul. 2022. "The Relationship between Figureheads and Managerial Leaders in the Private University Sector: A Decentralised, Competency-Based Leadership Model for Sustainable Higher Education" Sustainability 14, no. 19: 12279. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912279

APA StyleAlam, G. M. (2022). The Relationship between Figureheads and Managerial Leaders in the Private University Sector: A Decentralised, Competency-Based Leadership Model for Sustainable Higher Education. Sustainability, 14(19), 12279. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912279