How Did the COVID-19 Pandemic Affect Functional Relationships in Activities between Members in a Tourism Organization? A Case Study of Regional Tourism Organizations in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Stakeholders in Tourism

2.2. Impact of COVID-19 on Tourism

2.3. Idea of Regional Structures in Tourism

2.4. Organization of Tourism in Poland

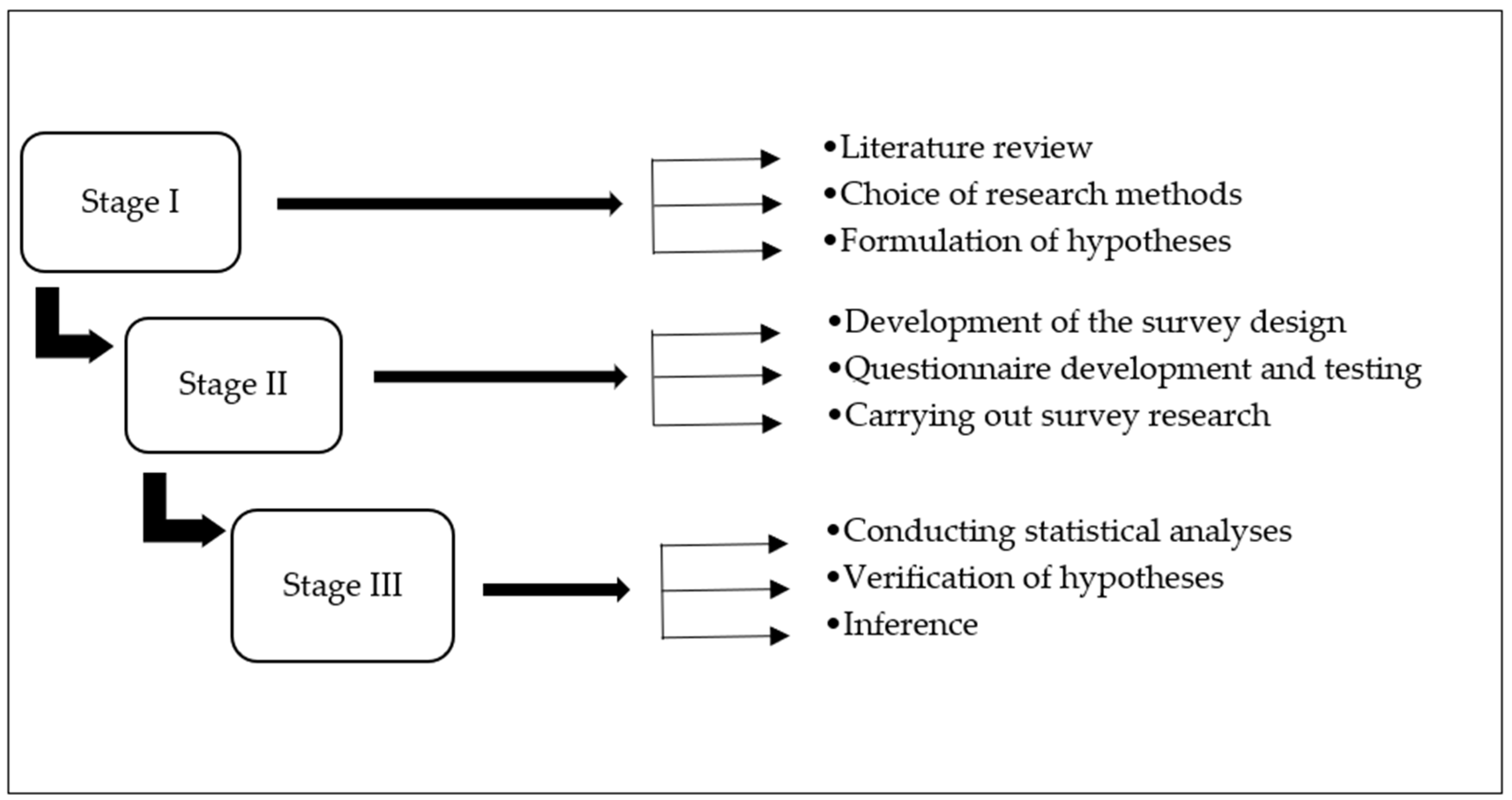

3. Materials and Methods

- Forms of the organization’s activity (including member support strategy) in the period before and during the COVID-19 pandemic,

- The nature of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the organization, especially regarding relations with members,

- Types of activities undertaken by the organization for the benefit of organization members in order to reduce the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic,

- Changes introduced in the organization’s model of activities and in the forms and types of relationships with members caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The importance of the activities of regional tourism organizations in the period before (BP) and during (DP) the COVID-19 pandemic;

- Forms of regional tourism organizations’ activities in the period before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, in terms of marketing activities (MA) and support strategies (SSA);

- Medians of point values broken down into variables of marketing activities (Mema) and variables of the support strategy (Mess);

- The nature of the pandemic’s impact on organizations (AR1–8—limitations of the organization’s activity, expressed by 8 partial variables), and their relations with member entities (SR1–3—structural relations-3 partial variables);

- Support for member entities during a pandemic, in terms of actions taken (AT1–8—8 partial variables) and planned actions (PA1–9—9 partial variables);

- Relationships between the impact on the activities of the organization (AR1–10), changes in relations with member entities (SR1–3), and the actions taken (AT1–8) and planned actions (PA1–9) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Further Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fedyk, W.; Sołtysik, M.; Bagińska, J.; Ziemba, M.; Kołodziej, M.; Borzyszkowski, J. Changes in DMO’s Orientation and Tools to Support Organizations in the Era of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, F.; van Niekerk, M.; Koseoglu, M.A.; Bilgihan, A. Interdisciplinary research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Overtourism? Understanding and Managing Urban Tourism Growth Beyond Perceptions. 2018. Available online: www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284419999 (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Andriotis, K. Community Groups Perceptions of and Preferences for Tourism Development: Evidence from Crete. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2005, 29, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, S.; Sharples, M.; Foster, C. Stakeholder engagement in the design of scenarios of technology-enhanced tourism services. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 4, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šegota, T.; Mihalič, T.; Kuščer, K. The impact of residents’ informedness and involvement on their perceptions of tourism impacts: The case of Bled. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavan, B. Tourism stakeholder exclusion and conflict in a small island. Leis. Stud. 2017, 36, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatipoglu, B.; Alvarez, M.D.; Ertuna, B. Barriers to stakeholder involvement in the planning of sustainable tourism: The case of the Thrace region in Turkey. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmyślony, P.; Pilarczyk, M. Identification of overtourism in Poznań through the analysis of social conflicts. Stud. Perieget. 2020, 30, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, E.T. Stakeholders in sustainable tourism development and their roles: Applying stakeholder theory to sustainable tourism development. Tour. Rev. 2007, 62, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hieu, V.M.; Rašovská, I. A proposed model on Stakeholders Impacting on Destination Management as mediator to achieve sustainable tourism development. Trendy V Podn. 2018, 8, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasian, S.; Onn, G.; Arnautovic, D. Overtourism in Dubrovnik in the eyes of local tourism employees: A qualitative study. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2020, 6, 1775944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Mendoza, H.; Santana Talavera, A.; León, C.J. The Role of Stakeholder Involvement in the Governance of Tourist Museums: Evidence of Management Models in the Canary Islands. Herit. Soc. 2018, 11, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiryluk, H.; Glińska, E.; Ryciuk, U.; Vierikko, K.; Rollnik-Sadowska, E. Stakeholders engagement for solving mobility problems in touristic remote areas from the Baltic Sea Region. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arizpe, M.; Arizpe, O.; Gamez, A. Communication and public participation processes in the sustainable tourism planning of the first capital of the Californias. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2008, 115, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ong, C.-E.; Minca, C.; Felder, M. The historic hotel as ‘quasi-freedom machine’: Negotiating utopian visions and dark histories at Amsterdam’s Lloyd Hotel and ‘Cultural Embassy’. J. Herit. Tour. 2014, 10, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzeszczyk, T. Metody Oceny Projektów z Dofinansowaniem Unii Europejskiej; Wydawnictwo Placet: Warszaw, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dolnicar, S.; Zare, S. COVID19 and Airbnb–Disrupting the Disruptor. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nientied, P. Rotterdam and the question of new urban tourism. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2020, 7, 344–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vegnuti, R. Cinque Terre, Italy—A case of place branding: From opportunity to problem for tourism. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2020, 12, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. 2020: Worst Year in Tourism History with 1 Billion Fewer International Arrivals. 2021. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/news/2020-worst-year-in-tourism-history-with-1-billion-fewer-international-arrivals (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Bausch, T.; Gartner, W.C.; Ortanderl, F. How to Avoid a COVID-19 Research Paper Tsunami? A Tourism System Approach. J. Travel Res. 2020, 60, 467–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uğur, N.G.; Akbıyık, A. Impacts of COVID-19 on global tourism industry: A cross-regional comparison. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 36, 100744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, P.; Chowdhary, N. Czy pandemia COVID-19 czasowo zatrzymała zjawisko overtourism? Turyzm/Tourism 2021, 31, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Martínez, C.L.; Kampmeier, S.; Kümpers, P.; Schwierzeck, V.; Hennies, M.; Hafezi, W.; Kühn, J.; Pavenstädt, H.; Ludwig, S.; Mellmann, A. A Pandemic in Times of Global Tourism: Superspreading and Exportation of COVID-19 Cases from a Ski Area in Austria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58, e00588-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, G.D.; Thomas, A.; Paul, J. Reviving tourism industry post-COVID-19: A resilience-based framework. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 37, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, S.; Botero, C.M. Beach Tourism in Times of COVID-19 Pandemic: Critical Issues, Knowledge Gaps and Research Opportunities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassler, P.; Fan, D.X. A tale of four futures: Tourism academia and COVID-19. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 38, 100818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godovykh, M.; Ridderstaat, J. Health outcomes of tourism development: A longitudinal study of the impact of tourism arrivals on residents’ health. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 17, 100462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.Z.; Ahmed, O.; Aibao, Z.; Hanbin, S.; Siyu, L.; Ahmad, A. Epidemic of COVID-19 in China and associated Psychological Problems. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 51, 102092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, F.; Nørfelt, A.; Josiassen, A.; Assaf, A.G.; Tsionas, M.G. Understanding the COVID-19 tourist psyche: The Evolutionary Tourism Paradigm. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 103053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Kock, F. The coronavirus pandemic–A critical discussion of a tourism research agenda. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Kozak, M.; Yang, S.; Liu, F. COVID-19: Potential effects on Chinese citizens’ lifestyle and travel. Tour. Rev. 2020, 76, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehto, X.; Davari, D.; Park, S. Transforming the guest–host relationship: A convivial tourism approach. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2020, 6, 1069–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomes, N. “Destroyer and Teacher”: Managing the Masses during the 1918–1919 Influenza Pandemic. Public Health Rep. 2010, 125, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seraphin, H.; Ivanov, S. Overtourism: A revenue management perspective. J. Revenue Pricing Manag. 2020, 19, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niezgoda, A.; Markiewicz, E.; Kowalska, K. Internal Substitution in the Tourism Market: Effects of the Covid-19 Pandemic; Poznań University of Economics and Business Press: Poznań, Poland, 2021; pp. 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Cahyanto, I.; Sajnani, M.; Shah, C. Changing dynamics and travel evading: A case of Indian tourists amidst the COVID 19 pandemic. J. Tour. Futur. 2021; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins-Kreiner, N.; Ram, Y. National tourism strategies during the Covid-19 pandemic. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 89, 103076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquin, A.G.; Schwitzguébel, A.C. Analysis of Barcelona’s tourist landscape as projected in tourism promotional videos. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2021, 7, 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzyszkowski, J. Organizacje Zarządzające Obszarami Recepcji Turystycznej. In Istota, Funkcjonowanie, Kierunki Zmian; Wydawnictwo Uczelniane Politechniki Koszalińskiej: Koszalin, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Baidal, J.A.I. REGIONAL TOURISM PLANNING IN SPAIN. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.P.F.; Muñoz, M.M.; Alarcón-Urbistondo, P. Regional tourism competitiveness using the PROMETHEE approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 73, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, R.; Khoo-Lattimore, C.; Arcodia, C. Understanding the contribution of stakeholder collaboration towards regional destination branding: A systematic narrative literature review. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamann, S. Destination Marketing Organizations in Europe. An In-Depth Analysis; Destination Marketing Association International (DMAI)–NHTV Breda University of Applied Sciences: Breda, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Critical research on the governance of tourism and sustainability. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nipa, N.J.; Sultana, J.; Rahman, H. Prospect of Private-Public Partnership in Tourism of Bangladesh. J. Investig. Manag. 2015, 4, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkoumas, A. Evaluating a standard for sustainable tourism through the lenses of local industry. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valente, F.; Dredge, D.; Lohmann, G. Leadership and governance in regional tourism. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, A. Regional Tourism Organisations in New Zealand form 1980 to 2005: Process of Transition and Change; Department of Tourism and Hospitality Management University of Waikato: Hamilton, New Zealand, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Klimek, K.; Doctor, M. Are alpine destination management organizations (DMOs) appropriate entities for the commercialization of summer tourism products? J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 10, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malenkina, N.; Ivanov, S. A linguistic analysis of the official tourism websites of the seventeen Spanish Autonomous Communities. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 204–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S.; Ives, C. The restructuring of New Zealand’s Regional Tourism Organisations. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 371–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presenza, A. The Performance of a Tourist Destination. Who Manages the Destination? Who Plays the Audit Role? University of Molise: Campobasso, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, B. The independence referendum in Scotland: A tourism perspective on different political options. J. Tour. Futur. 2016, 2, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalandides, A.; Kavaratzis, M.; Boisen, M.; Atorough, P.; Martin, A. The politics of destination marketing. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2012, 5, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedyk, W.; Sołtysik, M.; Oleśniewicz, P.; Borzyszkowski, J.; Weinland, J. Human resources management as a factor determining the organizational effectiveness of DMOs: A case study of RTOs in Poland. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 828–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeuring, J.H. Discursive contradictions in regional tourism marketing strategies: The case of Fryslân, The Netherlands. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2016, 5, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowska, J. Ścieżki rozwoju organizacyjnego turystyki w Polsce—Od rewolucyjnego po ewolucyjny system. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu 2012, 258, 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Zawilińska, B. Działalność lokalnych organizacji turystycznych w Karpatach Polskich. Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. W Krakowie 2010, 842, 103–119. [Google Scholar]

- Borzyszkowski, J. Organizacja i Zarządzanie Turystyką w Polsce; CeDeWu: Warszaw, Poland; Wyższa Szkoła Bankowa w Gdańsku: Gdańsk, Poland, 2011.

- USTAWA z dnia 25 czerwca 1999 r. o Polskiej Organizacji Turystycznej. Available online: https://www.pot.gov.pl/attachments/article/1420/Tekst%20jednolity%20ustawy%20o%20Polskiej%20Organizacji%20Turystycznej.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Morrison, A.M. Marketing and Managing Tourism Destinations; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S. Destination Marketing: An Integrated Marketing Communication Approach; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherland, 2008; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Dębski, M. Współpraca interesariuszy destynacji w procesie kreowania jej konkurencyjności. Organ. I Kierowanie. Organ. Manag. 2012, 152, 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Walas, B. Marketingowa Strategii Rozwoju Turystyki POT 2012–2020; Polska Organizacja Turystyczna: Warszawa, Poland, 2012.

- Ministerstwo Rozwoju, Pracy i Technologii. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/rozwoj-praca-technologia/departament-turystyki. (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Żegleń, P.; Rzepko, M. Działalność regionalnych organizacji turystycznych (ROT-ów) i ich wpływ na rozwój turystyki w regionie na przykładzie Podkarpackiej Regionalnej Organizacji Turystycznej. Ekon. Probl. Tur. 2018, 41, 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Lulewicz-Sas, A. Ewaluacja jako narzędzie doskonalenia organizacji. Optimum. Stud. Ekon. 2013, 3, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedyk, W.; Morawski, M. Regionalne organizacje turystyczne—Organizacjami współpracy. Prawda czy fałsz? Folia Tur. 2014, 32, 241–274. [Google Scholar]

- Fedyk, W. Struktura zarządów regionalnych organizacji turystycznych w Polsce jako uwarunkowanie skuteczności działania organizacji. Rozpr. Nauk. Akad. Wych. Fiz. We Wrocławiu 2015, 51, 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- Fedyk, W. Regionalne organizacje turystyczne jako Destination Management Company—Probiznesowy model działania. Folia Tur. 2018, 47, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedyk, W.; Morawski, M.; Bakowska-Morawska, U.; Langer, F.; Jandová, S. Model of cooperation in the network of non-enterprise organizations on the example of Regional Tourist Organizations in Poland. Ekon. Probl. Tur. 2018, 44, 113–137. [Google Scholar]

- Fedyk, W.; Kachniewska, M. Uwarunkowania skuteczności funkcjonowania regionalnych organizacji turystycznych w Polsce w formule klastra. Ekon. Probl. Tur. 2016, 33, 135–150. [Google Scholar]

- Gołembski, G.; Niezgoda, A. Organization of tourism in Poland after twenty years of systemic changes. In European Tourism Planning and Organisation Systems: The EU Member States; Costa, C., Panyik, E., Buhalis, D., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2014; pp. 243–256. [Google Scholar]

- Fortes, S.; Mantovaneli Junior, O. Desarrollo regional y turismo enBrasil. políticasenel Valle Europeo. Estud. Y Perspect. Tur. 2009, 18, 655–671. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, S.; Scott, N. Successful tourism clusters: Passion in paradise. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 46, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Collaborative destination marketing: A case study of Elkhart county, Indiana. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shouk, M.A. Destination management organizations and destination marketing: Adopting the business model of e-portals in engaging travel agents. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 35, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejarque-Bernet, J. Modelosinnovadores de Gestión y Promo-Comercializaciónturísticaen un Entorno de Competencia; XIV CongresoAECIT: Gijón, Spain, 2010; pp. 645–662. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, A. COVID-19 crisis: A new model of tourism governance for a new time. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2020, 12, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cehan, A.; Eva, M.; Iațu, C. A multilayer network approach to tourism collaboration. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuščer, K.; Eichelberger, S.; Peters, M. Tourism organizations’ responses to the COVID-19 pandemic: An investigation of the lockdown period. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 25, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillmayer, M.; Scherle, N.; Volchek, K. Destination Management in Times of Crisis-Potentials of Open Innovation Approach in the Context of COVID-19? In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Wörndl, W., Koo, C., Stienmetz, J.L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ritchie, B.W.; Verreynne, M. Building tourism organizational resilience to crises and disasters: A dynamic capabilities view. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 882–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabiddu, F.; Lui, T.-W.; Piccoli, G. Managing value co-creation in the tourism industry. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 42, 86–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihova, I.; Buhalis, D.; Moital, M.; Gouthro, M.B. Social layers of customer-to-customer value co-creation. J. Serv. Manag. 2013, 24, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trunfio, M.; della Lucia, M. Co-creating value in destination management levering on stakeholder engagement. E Rev. Tour. Res. 2019, 16, 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, T.; Hai, N.T.T. Hospitality, tourism, human rights and the impact of COVID-19. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2397–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, K.; Nhamo, G.; Chikodzi, D. COVID-19 cripples global restaurant and hospitality industry. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 1487–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.T.; Park, J.; Li, S.; Song, H. Social costs of tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orchiston, C.; Prayag, G.; Brown, C. Organizational resilience in the tourism sector. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 56, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.W.; Jiang, Y. A review of research on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management: Launching the annals of tourism research curated collection on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 79, 102812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawalha, I. Managing adversity: Understanding some dimensions of organizational resilience. Manag. Res. Rev. 2015, 38, 346–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Before the Pandemic BP | During the Pandemic DP | MED±QD Differences | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marketing activities (MA) | ||||

| Traditional promotional activities | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 3.0 ± 0.5 | −2.0 ± 0.75 | 0.002 |

| Modern promotional activities | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 0.169 |

| Tourist information | 5.0 ± 0.5 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | −0.5 ± 1.0 | 0.012 |

| Service reservation | 1.0 ± 1.75 | 2.5 ± 2.0 | 0.0 ± 1.25 | 0.441 |

| Product development | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 4.0 ± 0.5 | −0.5 ± 0.5 | 0.024 |

| Support strategy activities (SSA) | ||||

| Planning of tourism development | 4.0 ± 0.25 | 4.0 ± 0.75 | 0.0 ± 0.75 | 0.959 |

| Development of human resources | 4.0 ± 0.0 | 4.0 ± 0.75 | 0.0 ± 0.75 | 0.767 |

| Development of ICT | 4.0 ± 1.5 | 5.0 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 0.008 |

| Crisis management | 2.5 ± 0.75 | 4.5 ± 1.0 | 1.5 ± 0.75 | 0.003 |

| Cooperation with the environment | 5.0 ± 0.5 | 5.0 ± 0.5 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.345 |

| Promoting the idea of sustainable development | 4.0 ± 0.75 | 4.0 ± 0.75 | 0.0 ± 0.5 | 0.477 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fedyk, W.; Sołtysik, M.; Bagińska, J.; Ziemba, M.; Kołodziej, M.; Borzyszkowski, J. How Did the COVID-19 Pandemic Affect Functional Relationships in Activities between Members in a Tourism Organization? A Case Study of Regional Tourism Organizations in Poland. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12671. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912671

Fedyk W, Sołtysik M, Bagińska J, Ziemba M, Kołodziej M, Borzyszkowski J. How Did the COVID-19 Pandemic Affect Functional Relationships in Activities between Members in a Tourism Organization? A Case Study of Regional Tourism Organizations in Poland. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):12671. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912671

Chicago/Turabian StyleFedyk, Wojciech, Mariusz Sołtysik, Justyna Bagińska, Mateusz Ziemba, Małgorzata Kołodziej, and Jacek Borzyszkowski. 2022. "How Did the COVID-19 Pandemic Affect Functional Relationships in Activities between Members in a Tourism Organization? A Case Study of Regional Tourism Organizations in Poland" Sustainability 14, no. 19: 12671. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912671

APA StyleFedyk, W., Sołtysik, M., Bagińska, J., Ziemba, M., Kołodziej, M., & Borzyszkowski, J. (2022). How Did the COVID-19 Pandemic Affect Functional Relationships in Activities between Members in a Tourism Organization? A Case Study of Regional Tourism Organizations in Poland. Sustainability, 14(19), 12671. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912671