Regional Governance for Food System Transformations: Learning from the Pacific Island Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Documentary Data

2.2.2. Qualitative Interviews

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

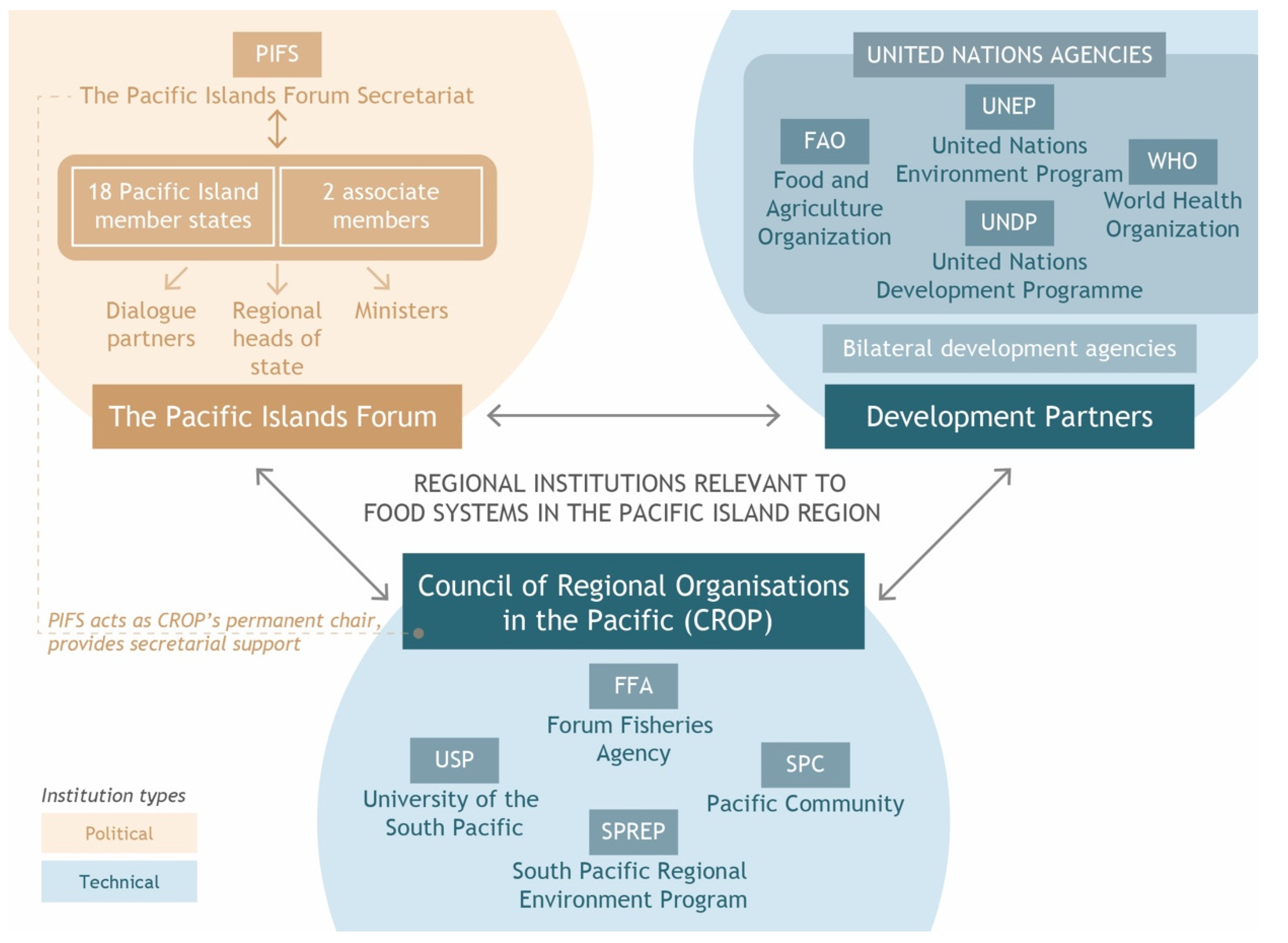

3.1. Institutional Structures Relevant to Food Systems

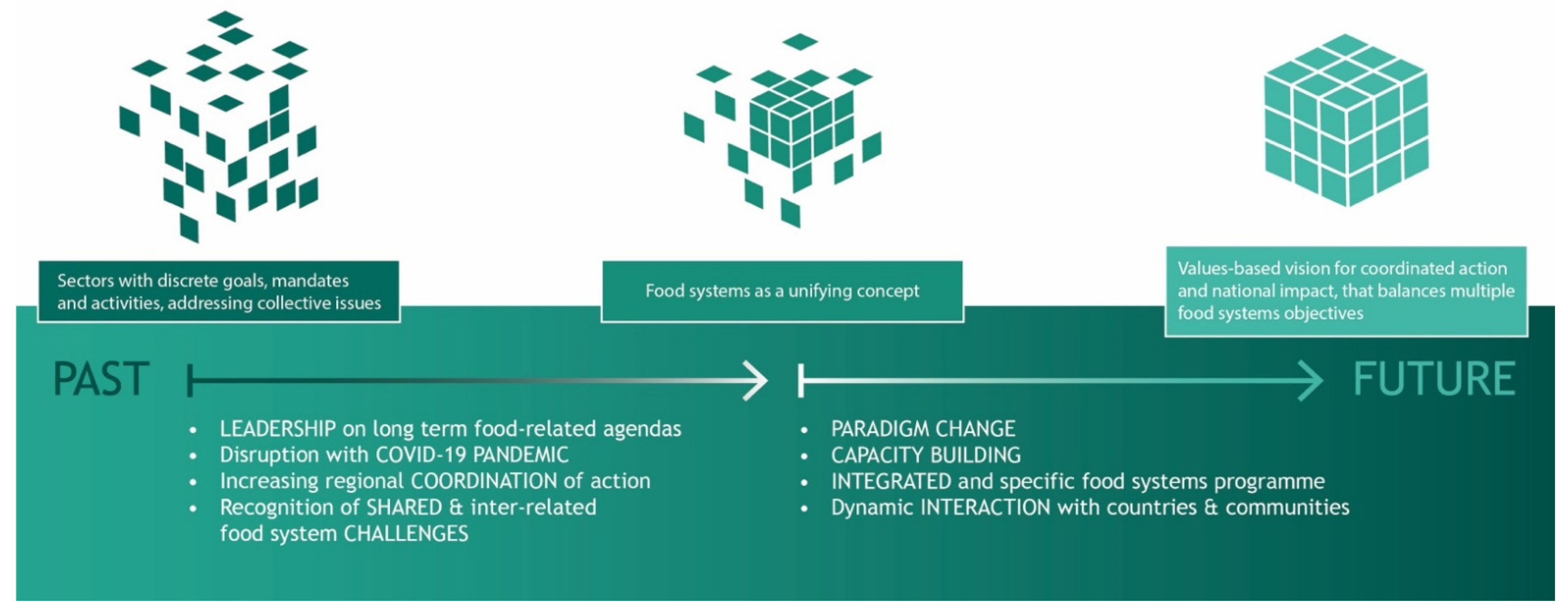

3.2. Evolution and Disruption in Regional Food Systems Governance

3.2.1. Existing Coordination and Integration Relevant to Food Systems

3.2.2. Movement towards ‘Food Systems’ at the Regional Level

“The language around [food systems] and the approach is something which is not fully understood. … that needs to be articulated in a way which everybody can see their role within it. So … it’s useful to have this discussion, to build that awareness, to show that how people are engaged in food systems and how they can build upon it. … I think, for the region, it’s pretty new.”(#8_environment_regional)

3.2.3. Recent Food System Disruption with the COVID-19 Pandemic

3.3. Perception of the Purpose of a Regional Approach to Food Systems

3.3.1. Address Multiple Shared and Inter-Related Challenges Related to Food Systems

“laissez faire market forces do not necessarily deliver what’s considered by governments to be the desirable food systems outcome.”(#5_fisheries_regional)

3.3.2. Improve Coordination across Silos

“Because invariably, those of us working in the agriculture space and in the coastal fisheries space are talking to exactly the same communities… It’s about trying to join our offerings up.”(#19_health_DevPartner)

“…too often we concentrate on the economics and the financial gains, but we don’t factor in …sustainability [or] quality of life.”(#4_environment_DevPartner)

3.3.3. Facilitate Constructive Engagement on Policy Issues between International, Regional and National Actors

“It started from those community workshops … Fiji, took that onto the regional meeting. And out of that regional meeting… it’s taken back to the countries. And then eventually it’ll go to the international forum. And whatever is decided at the international forum should come down to the region from the region, run down to the nations, nations, then it comes down to the government, NGOs, and to the community. That’s the pathway.”(#2_environment_NGO)

“A lot of traditional structures [related to the environment and conservation] have either been minimized or weakened. Bringing them back at the national level is sometimes hard. But when you have agreed …regional declarations, then it makes it easier for government to make some of these hard decisions because they don’t feel like they’re doing it alone. It’s something that we’ve all agreed we’d do.”(#4_environment_DevPartner)

3.4. Characteristics of a “Good” Regional Approach to Food Systems in the Pacific Island Region

3.4.1. Rooted in Values

“I think it helped us to project, from a perspective of authority as a region, that we actually contributed very significantly to the global food system. We produce over 50% of the world’s tuna…. it helped highlight our traditional capability and the resilience that that brings to our food systems, as well as the contribution to the global environment.”(#12_environment_regional)

3.4.2. Meeting Multiple Objectives

“…so it’s not only looking at resources and revenue through fisheries… but it’s really what defines the Pacific people. … it’s really how that looks at livelihoods of our people, the health and nutrition that comes through this… the resources that comes from the ocean, which gives food security.”(#9_strategic_regional)

“…that blue economy side of it seems to be an area which is going to be critically important for the Pacific, getting that right in terms of the economics associated with fishing is something which we all would need to get on top of because it’s such a big earner for many parts of the Pacific.”(#8_environment_regional)

“There’s that nexus between natural foods and having a healthy ecosystem.”(#4_environment_DevPartner)

“…[we need] to put in place things that help communities to be able to live healthier lifestyles but also be able to accrue some [economic] benefit. [Although] Maybe not as much economic benefit as they would have if they’d cultivated, say, rice instead of traditional crops.”(#4_environment_DevPartner)

3.4.3. Balancing Tensions

“We would like to concentrate on producing good food and preserving the environment, but it has to balance with what’s economical.”(#2_environment_NGO)

“the food system is struggling to deliver sufficient nutritious food, but it’s also struggling to provide people with livelihoods as well… very vulnerable to external shocks, to climate change… It’s not a resilient system.”(#19_health_DevPartner)

“…we’ve got two things going: one is the push for commercialization and export of agricultural and forestry products, versus sustainability. We want to have a food system that is sustainable, but we want to scale that, and export. Governments are still really promoting systems that are not sustainable, in more intensive use of agrochemicals, shift to high levels of mechanization shifts to scale. All of these things if they’re not managed well, lead to some of the environmental damage that we’ve already got, and worse.”(#7_agriculture_regional)

3.4.4. Meaningful Support and Resources for Countries

“Regional frameworks …provide templates to countries who are often looking for that guidance and that expertise and we provide pooled capability to support.”(#12_environment_regional)

“we are a lending library of expertise”(#5_fisheries_regional)

“a regional public good to similar countries, similar members who are having similar issues because of climate change… Well, it can only be through a regional organization. It doesn’t come from a donor. It has to be a technical service.”(#1_strategic_regional)

“One of the mechanisms [is] creating dashboards and indicators. You might be familiar with the MANA dashboard in the public health space, there’s the coastal fishery scorecard. There are a lot of these different tools which exist.”(#14_strategic_regional)

3.5. Learnings for Strengthening a Regional Approach for Food Systems

3.5.1. Paradigm Change

“The scope of further improvement from here is getting out of our boxes and joining forces in a way which is more coordinated and more holistic.”(#5_fisheries_regional)

“[With respect to food systems] within our region, we do need to have the more philosophic and visionary language around how we work together, and what we do.”(#7_agriculture_regional)

3.5.2. Capacity Building

“They’ve had the silos approach for so long now, if we’re to make any quantum leaps or come up with game changing solutions, we are going to have to reach out beyond our own particular mandates and it’s going to take a team building approach to integrate the programming approach, taking a holistic view.”(#5_fisheries_regional)

“You will never get a unified program of work until you get a fungible source of programmatic funds that can be moved around commensurate with the absorptive capability of the country and the different ministries that needs to be a part of that journey.”(#12_environment_regional)

“USP [the University of the South Pacific], I think could have a growing role in the research piece, but also in the education piece. Ideally, we’ll start to have graduates coming out of USP in the relevant sectors that are coming out with an understanding of the systems approaches, and what is needed. I think they’ve got a valuable role to play as well but that’s a medium to long term change in what they’re teaching.”(#7_agriculture_regional)

3.5.3. New Modes of Coordination

“The risk is if we establish something too formal [for food systems], we’ll end up with another siloed framework. We want to avoid that.”(#7_agriculture_regional)

“Pick one or two things that are really catalytic as priorities for action.”(#3_strategic_DevPartner)

“When you say translation, it’s about making it suitable to the context of the country, where you take into consideration the culture, the accessibility, the work, the capacity of the country, and things like that.”(#21_health_regional)

3.5.4. Dynamic Interaction with Countries and Communities

“Before we develop a regional framework or policy, we need to consult members first. And if there is a political will and interest for us to go ahead to develop these policies or framework, then …we will have discussions with every stakeholder who are interested …consultations and coordination are key. …we want to see that there is an ownership from member states that, yes, they drive that process, and they want to bring that to its implementation.”(#15_strategic_regional)

“…you need the people who have this ability to be able to make these linkages and translate it…[to] bring down the information from the region to the nation, nation to the province, province right down to the community level.”(#2_environment_NGO)

“a lot of these micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) are the local ones. So if you want to empower local people… it’s important to look at some of these MSMEs [who] are really the genuine local producers.”(#17_environment_regional)

4. Discussion

5. Study Strengths and Limitations

6. Broader Reflections on Regional Food Systems Governance

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, J.; Ding, X.; Gao, H.; Fan, S. Reshaping Food Policy and Governance to Incentivize and Empower Disadvantaged Groups for Improving Nutrition. Nutrients 2022, 14, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Secretary-General’s Chair Summary and Statement of Action on the UN Food Systems. Summit: Inclusive and Transformative Food Systems Nourish Progress to Achieve Zero Hunger. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/food-systems-summit/news/making-food-systems-work-people-planet-and-prosperity (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- HLPE. Food Security and Nutrition: Building a Global Narrative Towards 2030; HLPE: Rome, Italy, 2020; Volume 112. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Sustainable Food Systems: Concepts and Framework; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Popkin, B.M.; Corvalan, C.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M. Dynamics of the double burden of malnutrition and the changing nutrition reality. Lancet 2020, 395, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, L.; Hawkes, C.; Webb, P.; Thomas, S.; Beddington, J.; Waage, J.; Flynn, D. A new global research agenda for food. Nature 2016, 540, 30–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition. Food Systems and Diets: Facing the Challenges of the 21st Century; Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinburn, B.A.; Kraak, V.I.; Allender, S.; Atkins, V.J.; Baker, P.I.; Bogard, J.R.; Brinsden, H.; Calvillo, A.; De Schutter, O.; Devarajan, R. The Global Syndemic of Obesity, Undernutrition, and Climate Change: The Lancet Commission report. Lancet 2019, 393, 791–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béné, C.; Oosterveer, P.; Lamotte, L.; Brouwer, I.D.; de Haan, S.; Prager, S.D.; Talsma, E.F.; Khoury, C.K. When food systems meet sustainability—Current narratives and implications for actions. World Dev. 2019, 113, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanzo, J.; Davis, C.; McLaren, R.; Choufani, J. The effect of climate change across food systems: Implications for nutrition outcomes. Glob. Food Secur. 2018, 18, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbow, C.; Rosenzweig, C.; Barioni, L.G.; Benton, T.G.; Herrero, M.; Krishnapillai, M.; Liwenga, E.; Pradhan, P.; Rivera-Ferre, M.G.; Sapkota, T.; et al. Food Security. In Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems; Shukla, P.R., Buendia, J.S.E.C., Masson-Delmotte, V., Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Zhai, P., Slade, R., Connors, S., van Diemen, R., Ferrat, M., et al., Eds.; NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS): New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, S.; Teng, P.; Chew, P.; Smith, G.; Copeland, L. Food system resilience and COVID-19–Lessons from the Asian experience. Glob. Food Secur. 2021, 28, 100501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klassen, S.; Murphy, S. Equity as both a means and an end: Lessons for resilient food systems from COVID-19. World Dev. 2020, 136, 105104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020. Transforming Food Systems for Affordable Diets; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020.

- Rosenzweig, C.; Mbow, C.; Barioni, L.G.; Benton, T.G.; Herrero, M.; Krishnapillai, M.; Liwenga, E.T.; Pradhan, P.; Rivera-Ferre, M.G.; Sapkota, T. Climate change responses benefit from a global food system approach. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thow, A.M.; Greenberg, S.; Hara, M.; Friel, S.; Sanders, D. Improving policy coherence for food security and nutrition in South Africa: A qualitative policy analysis. Food Secur. 2018, 10, 1105–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, S.M.; Thow, A.M.; Ghosh-Jerath, S.; Leeder, S.R. Identifying the Barriers and Opportunities for Enhanced Coherence between Agriculture and Public Health Policies: Improving the Fat Supply in India. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2015, 54, 603–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkes, C.; Thow, A.M.; Downs, S.; Ghosh-Jerath, S.; Snowdon, W.; Morgan, E.; Thiam, I.; Jewell, J. Leveraging agriculture and food systems for healthier diets and noncommunicable disease prevention: The need for policy coherence. In Expert Paper for the Second International Conference on Nutrition; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Reeve, E.; Ravuvu, A.; Farmery, A.; Mauli, S.; Wilson, D.; Johnson, E.; Thow, A.-M. Strengthening Food Systems Governance to Achieve Multiple Objectives: A Comparative Instrumentation Analysis of Food Systems Policies in Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Schutter, O.; Jacobs, N.; Clément, C. A ‘Common Food Policy’ for Europe: How governance reforms can spark a shift to healthy diets and sustainable food systems. Food Policy 2020, 96, 101849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börzel, T.A. Theorizing Regionalism: Cooperation, Integration, and Governance. In The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Regionalism; Börzel, T.A., Risse, T., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 41–63. [Google Scholar]

- Söderbaum, F. Theories of regionalism. In Routledge Handbook of Asian Regionalism; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, K.A. The WTO and regional/bilateral trade agreements. In Handbook of International Trade Agreements; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Fry, G. The ‘new’ Pacific diplomacy and the transformation of regionalism. In Framing the Islands; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2019; pp. 275–304. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd, R.; Reeve, E.; Sparks, E.; George, A.; Vivili, P.; Tin, S.T.W.; Buresova, D.; Webster, J.; Thow, A.-M. The politics of food in the Pacific: Coherence and tension in regional policies on nutrition, the food environment and non-communicable diseases. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morioka, K.; McGann, M.; Mackay, S.; Mackey, B. Applying information for national adaptation planning and decision making: Present and future practice in the Pacific Islands. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2020, 20, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, M.R.; Schwarz, A.-M.; Wini-Simeon, L. Towards defining the Blue Economy: Practical lessons from pacific ocean governance. Mar. Policy 2018, 88, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hau’ofa, E. Our Sea of Islands. In We Are the Ocean: Selected Works; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2008; pp. 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Malielegaoi, T.L.S. Remarks by Hon. Tuilaepa Lupesoliai Sailele Malielegaoi Prime Minister of the Independent State of Samoa at the High-Level Pacific Regional Side Event by PIFS on Our Values and Identity as Stewards of the World’s Largest Oceanic Continent, The Blue Pacific. Available online: https://www.forumsec.org/2017/06/05/remarks-by-hon-tuilaepa-lupesoliai-sailele-malielegaoi-prime-minister-of-the-independent-state-of-samoa-at-the-high-level-pacific-regional-side-event-by-pifs-on-our-values-and-identity-as-stewards/ (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Fry, G. Conclusion: Power and diplomatic agency in Pacific regionalism. In Framing the Islands; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2019; pp. 305–326. [Google Scholar]

- Latu, C.; Moodie, M.; Coriakula, J.; Waqa, G.; Snowdon, W.; Bell, C. Barriers and Facilitators to Food Policy Development in Fiji. Food Nutr. Bull. 2018, 39, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waqa, G.; Bell, C.; Snowdon, W.; Moodie, M. Factors affecting evidence-use in food policy-making processes in health and agriculture in Fiji. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmery, A.K.; Kajlich, L.; Voyer, M.; Bogard, J.R.; Duarte, A. Integrating fisheries, food and nutrition–Insights from people and policies in Timor-Leste. Food Policy 2020, 91, 101826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krapohl, S. Games regional actors play: Dependency, regionalism, and integration theory for the Global South. J. Int. Relat. Dev. 2020, 23, 840–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grbich, C. Qualitative Research in Health: An Introduction; Allen & Unwin: Sydney, Australia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Börzel, T.A.; Risse, T. Grand theories of integration and the challenges of comparative regionalism. J. Eur. Public Policy 2019, 26, 1231–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatier, P. Knowledge, policy-oriented learning and policy change: An advocacy coalition framework. Sci. Commun. 1987, 8, 649–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P.A. Policy Paradigms, Social Learning, and the State: The Case of Economic Policymaking in Britain. Comp. Polit. 1993, 25, 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivusalo, M.; Schrecker, T.; Labonté, R. Globalization and Policy Space for Health and Social Determinants of Health. In Globalization and Health: Pathways, Evidence and Policy; Ronald Labonte, T.S., Packer, C., Runnels, V., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew, N.L.; Allison, E.H.; Brewer, T.; Connell, J.; Eriksson, H.; Eurich, J.G.; Farmery, A.; Gephart, J.A.; Golden, C.D.; Herrero, M.; et al. Continuity and change in the contemporary Pacific food system. Glob. Food Secur. 2022, 32, 100608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition. Nutrition and Food Systems; United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, E. Research for Health Policy; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bacchi, C. Introducing the ‘What’s the problem represented to be?’approach. In Engaging with Carol Bacchi: Strategic Interventions and Exchanges; University of Adelaide Press: Adelaide, Australia, 2012; pp. 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Iese, V.; Wairiu, M.; Hickey, G.M.; Ugalde, D.; Salili, D.H.; Walenenea Jr, J.; Tabe, T.; Keremama, M.; Teva, C.; Navunicagi, O. Impacts of COVID-19 on agriculture and food systems in Pacific Island countries (PICs): Evidence from communities in Fiji and Solomon Islands. Agric. Syst. 2021, 190, 103099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, P.; Thow, A.M.; Tutuo Wate, J.; Nonga, N.; Vatucawaqa, P.; Brewer, T.; Sharp, M.K.; Farmery, A.; Trevena, H.; Reeve, E.; et al. COVID-19 and Pacific food system resilience: Opportunities to build a robust response. Food Secur. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsy, H.; Salami, A.; Mukasa, A.N. Opportunities amid COVID-19: Advancing intra-African food integration. World Dev. 2021, 139, 105308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candel, J. EU food-system transition requires innovative policy analysis methods. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 296–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thow, A.M.; Apprey, C.; Winters, J.; Stellmach, D.; Alders, R.; Aduku, L.N.E.; Mulcahy, G.; Annan, R. Understanding the Impact of Historical Policy Legacies on Nutrition Policy Space: Economic Policy Agendas and Current Food Policy Paradigms in Ghana. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2020, 10, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruben, R.; Cavatassi, R.; Lipper, L.; Smaling, E.; Winters, P. Towards food systems transformation—five paradigm shifts for healthy, inclusive and sustainable food systems. Food Secur. 2021, 13, 1423–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alders, R.G.; Ratanawongprasat, N.; Schönfeldt, H.; Stellmach, D. A planetary health approach to secure, safe, sustainable food systems: Workshop report. Food Secur. 2018, 10, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, P.; Taherzadeh, A. Working Co-operatively for Sustainable and Just Food System Transformation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, T.; Tschirley, D.; Liverpool-Tasie, L.S.O.; Awokuse, T.; Fanzo, J.; Minten, B.; Vos, R.; Dolislager, M.; Sauer, C.; Dhar, R.; et al. The processed food revolution in African food systems and the double burden of malnutrition. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 28, 100466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krapohl, S.; Fink, S. Different Paths of Regional Integration: Trade Networks and Regional Institution-Building in Europe, Southeast Asia and Southern Africa. JCMS J. Common Mark. Stud. 2013, 51, 472–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börzel, T.A.; Risse, T. Identity Politics, Core State Powers and Regional Integration: Europe and beyond. JCMS J. Common Mark. Stud. 2020, 58, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, E.D.; Solingen, E. Regionalism. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2010, 13, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukuitonga, C. The future of Pacific regionalism: Challenges and prospects (Macmillan Brown lecture series for 2016). Pac. Dyn. J. Interdiscip. Res. 2017, 1, 340–347. [Google Scholar]

- Swinburn, B. Power Dynamics in 21st-Century Food Systems. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.; Leach, M. Transforming Food Systems: The Potential of Engaged Political Economy. Available online: https://bulletin.ids.ac.uk/index.php/idsbo/article/view/3041/Online%20article (accessed on 1 October 2022).

| Primary Area of Expertise (n = 21) | Institutional Representation (n = 21) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceans/Fisheries | Health | Land/Agriculture | Environment | Economic/Strategic | Regional Agency | Development Partner | NGO |

| 2 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 11 | 8 | 2 |

| Code (Group) | Sub-Codes |

|---|---|

| Purpose of Pacific regionalism | |

| How does regionalism work in practice | Regionalism in practice |

| Regional agency activities and priorities | |

| Influences on regional agreements | |

| Regional–national interface | |

| Food system policy | Food system priorities (regional) |

| Food system priorities (national) | |

| Challenges for food systems policy | |

| Success in food systems policy and agenda setting | |

| Food systems (ideas and narratives) | |

| Capacities | Narratives about capacity (regional) |

| Narratives about capacity (national) | |

| Actors | Private sector |

| Regional institutions | |

| National government | |

| Civil Society Organizations | |

| United Nations and other international institutions | |

| Academia | |

| Champions | |

| Where research could contribute | |

| Opportunities to improve food systems and policy | |

| Integration of nutrition and environment | |

| Frames | Environment |

| Nutrition | |

| Economic issues | |

| Gender | |

| Regional Commitment or Strategy | Institutional Origin | Stated Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Pacific Leaders Gender Equality Declaration endorsed in 2012 | Endorsed by Pacific Islands Forum Leaders | “Leaders commit to implement specific national policy actions to progress gender equality in the areas of gender responsive government programs and policies, decision making, economic empowerment, ending violence against women, and health and education” |

| Framework for Pacific Regionalism, 2014 | Endorsed by Pacific Islands Forum Leaders | “Our principal objectives are: Sustainable development that combines economic social, and cultural development in ways that improve livelihoods and well-being and use the environment sustainably; Economic growth that is inclusive and equitable; Strengthened governance, legal, financial, and administrative systems; and Security that ensures stable and safe human, environmental and political conditions for all.” (p. 3) |

| Small Island Developing States Accelerated Modalities of Action (Samoa Pathway), 2014 | UN General Assembly | “The present Samoa Pathway presents a basis for action in the agreed priority areas [for the sustainable development of small island developing States]” (p. 10) |

| A Roadmap for Responding to the Non-Communicable Disease (NCD) Crisis in the Pacific (2014) DRAFT | World Bank | “This report responds to the request by the Forum Economic Ministers Meeting (FEMM) for a ‘Roadmap’ to respond to NCDs… This proposed Roadmap is intended to help ‘operationalise’ the already agreed [global] frameworks and strategies for responding to NCDs in ways that are affordable and cost-effective.” (p. 19) |

| The Pacific Youth Development Framework,2014–2023 | SPC, with Pacific Youth Council | “The framework aims to be a catalyst for investment in youth, rather than a regional youth programme. It aims to facilitate shared decision-making based on evidence and contributions from relevant communities of practice, and to support Pacific Island countries and territories in implementing their development objectives for youth.” (p. 3) |

| Regional Roadmap for Sustainable Pacific Fisheries, 2015–2025 | FFA and SPC | The Roadmap sets clear goals and targets against which progress will be measured. (p. 1) |

| New Song for Coastal Fisheries, 2015 | SPC Heads of Fisheries; Forum Fisheries Committee; Ministerial Forum Fisheries Committee Meeting | “The ‘new song’ is the innovative approach to dealing with declines in coastal fisheries resources and related ecosystems… designed to provide direction and encourage coordination, cooperation and an effective use of regional and other support services in the development of coastal fisheries management. At the regional level, it brings together initiatives and stakeholders with a shared vision of coastal fisheries management” (p. III) |

| Cleaner Pacific 2025: The Pacific Regional Waste and Pollution Management Strategy, 2016–2025 | Secretariat of SPREP | “The Pacific Regional Waste and Pollution Management Strategy 2016–2025 is a comprehensive blueprint to help improve the management of waste and pollution over the next ten years. It was developed in full consultation with 21 member countries and has captured the waste and pollution management priorities of the region.” (p. 3) |

| The Pacific Roadmap for Sustainable Development endorsed in 2017 | Leaders of the Pacific Islands Forum | “The roadmap outlines how the region will track and report on its progress against regional actions and the means of implementation for sustainable development in the Pacific.” (p. 2) |

| Framework for Resilient Development in the Pacific: An Integrated Approach to Address Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management, 2017–2030 | PIFS; SPC; SPREP; Special Representative of the Secretary-General; United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction | “The Framework for Resilient Development in the Pacific: An Integrated Approach to Address Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management provides high level strategic guidance to different stakeholder groups on how to enhance resilience to climate change and disasters, in ways that contribute to and are embedded in sustainable development.” (p. 2) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thow, A.M.; Ravuvu, A.; Iese, V.; Farmery, A.; Mauli, S.; Wilson, D.; Farrell, P.; Johnson, E.; Reeve, E. Regional Governance for Food System Transformations: Learning from the Pacific Island Region. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12700. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912700

Thow AM, Ravuvu A, Iese V, Farmery A, Mauli S, Wilson D, Farrell P, Johnson E, Reeve E. Regional Governance for Food System Transformations: Learning from the Pacific Island Region. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):12700. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912700

Chicago/Turabian StyleThow, Anne Marie, Amerita Ravuvu, Viliamu Iese, Anna Farmery, Senoveva Mauli, Dorah Wilson, Penny Farrell, Ellen Johnson, and Erica Reeve. 2022. "Regional Governance for Food System Transformations: Learning from the Pacific Island Region" Sustainability 14, no. 19: 12700. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912700

APA StyleThow, A. M., Ravuvu, A., Iese, V., Farmery, A., Mauli, S., Wilson, D., Farrell, P., Johnson, E., & Reeve, E. (2022). Regional Governance for Food System Transformations: Learning from the Pacific Island Region. Sustainability, 14(19), 12700. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912700