Commercial Real Estate Market at a Crossroads: The Impact of COVID-19 and the Implications to Future Cities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Data

4. Method

5. Results

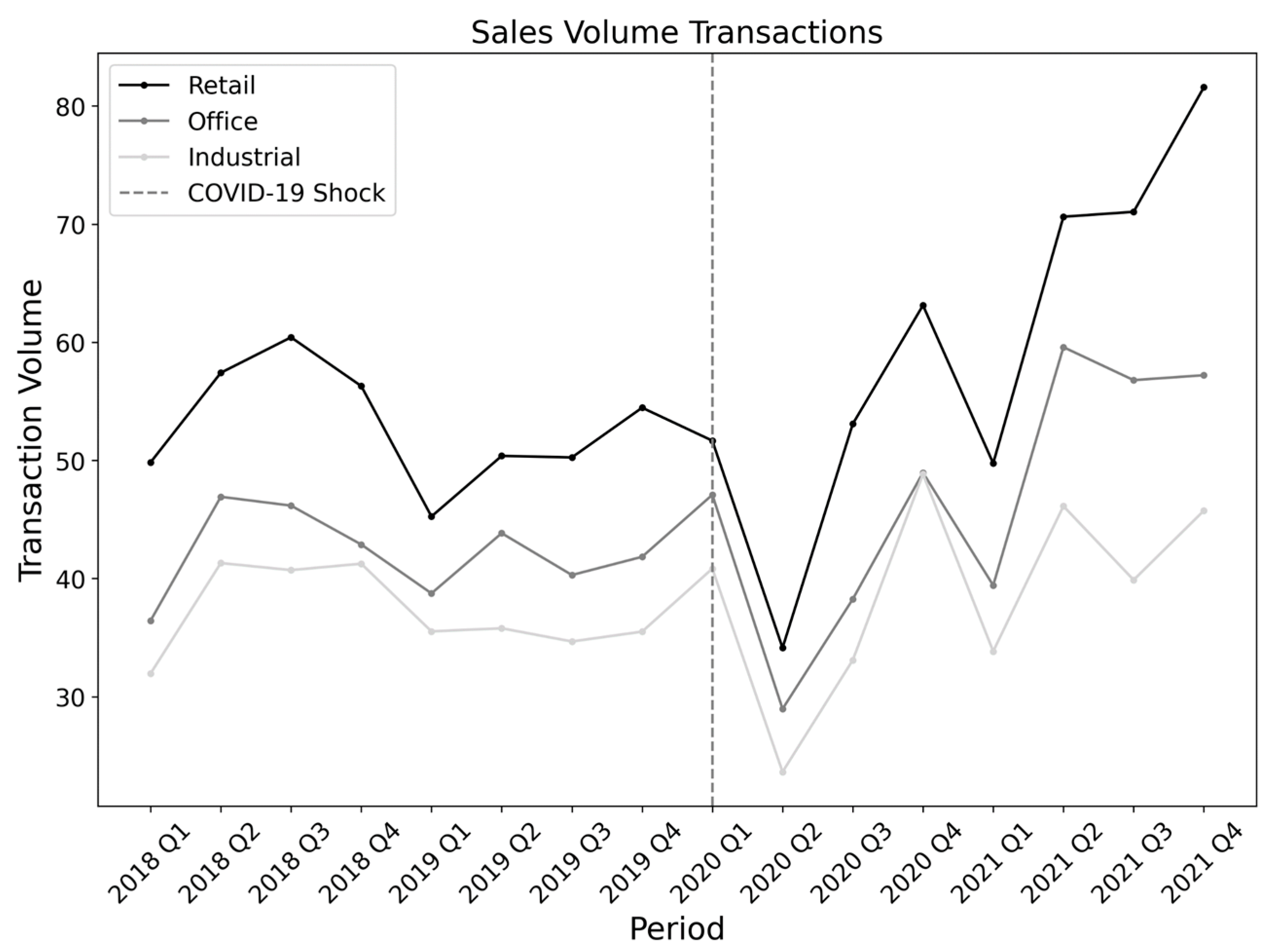

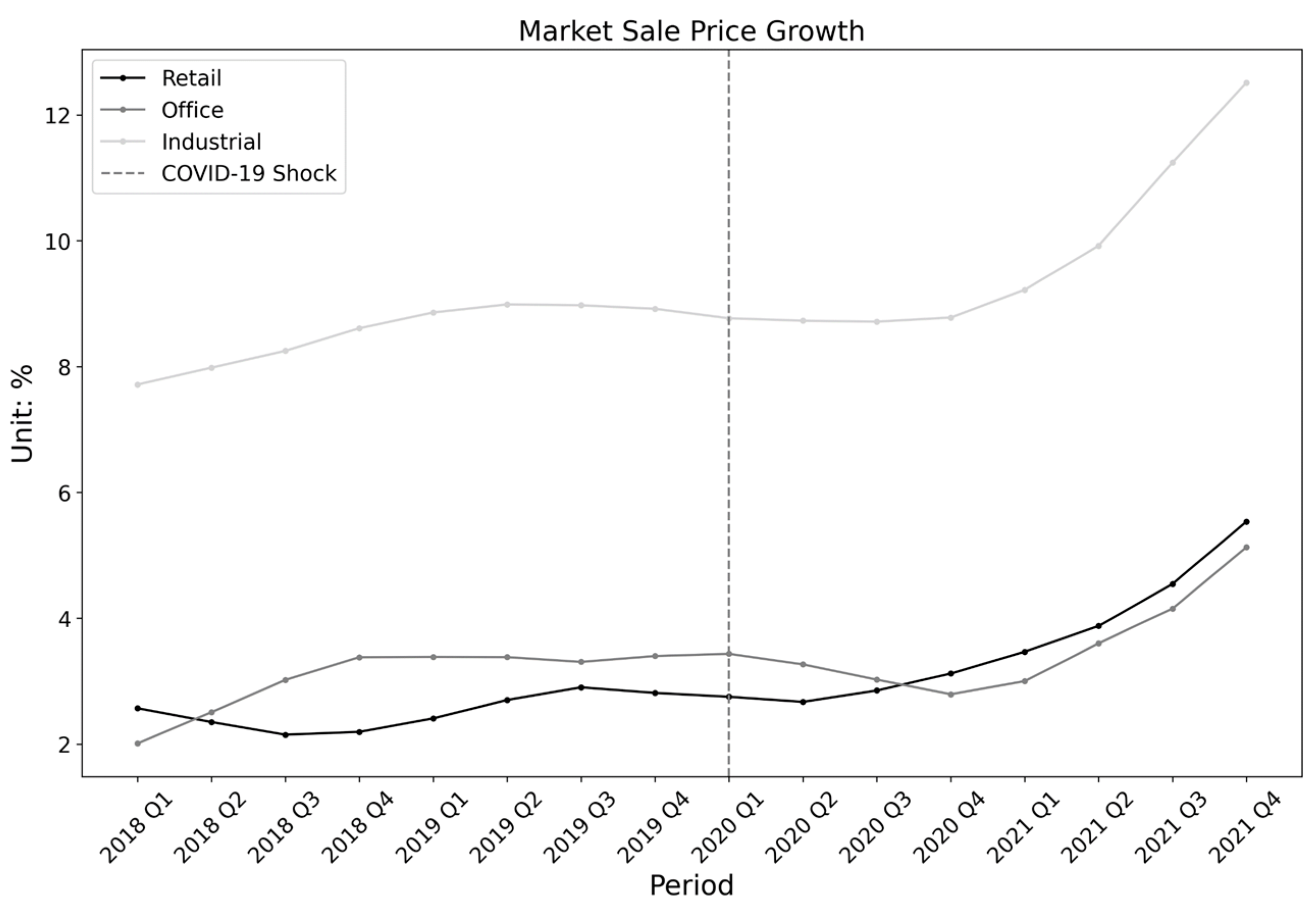

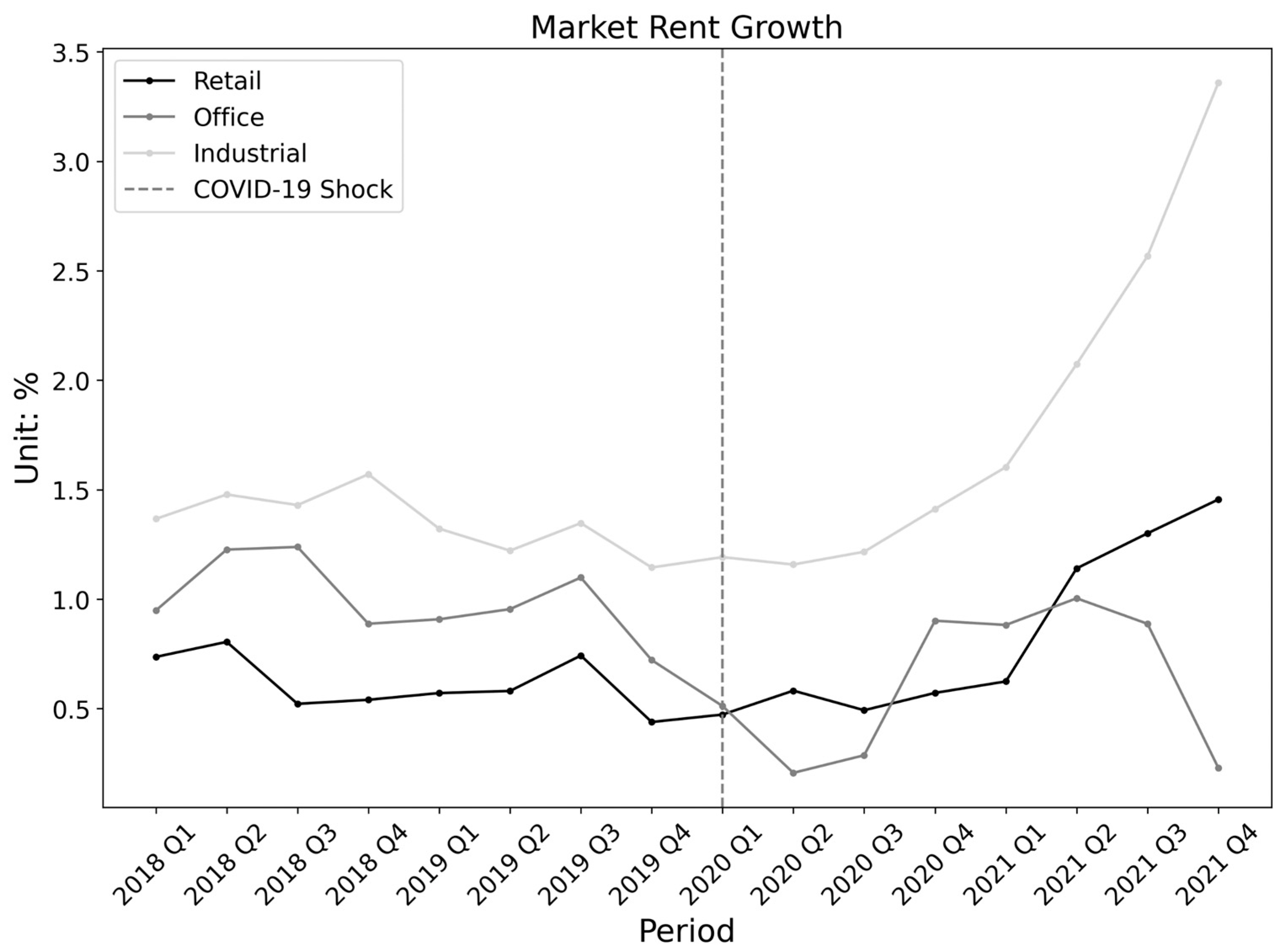

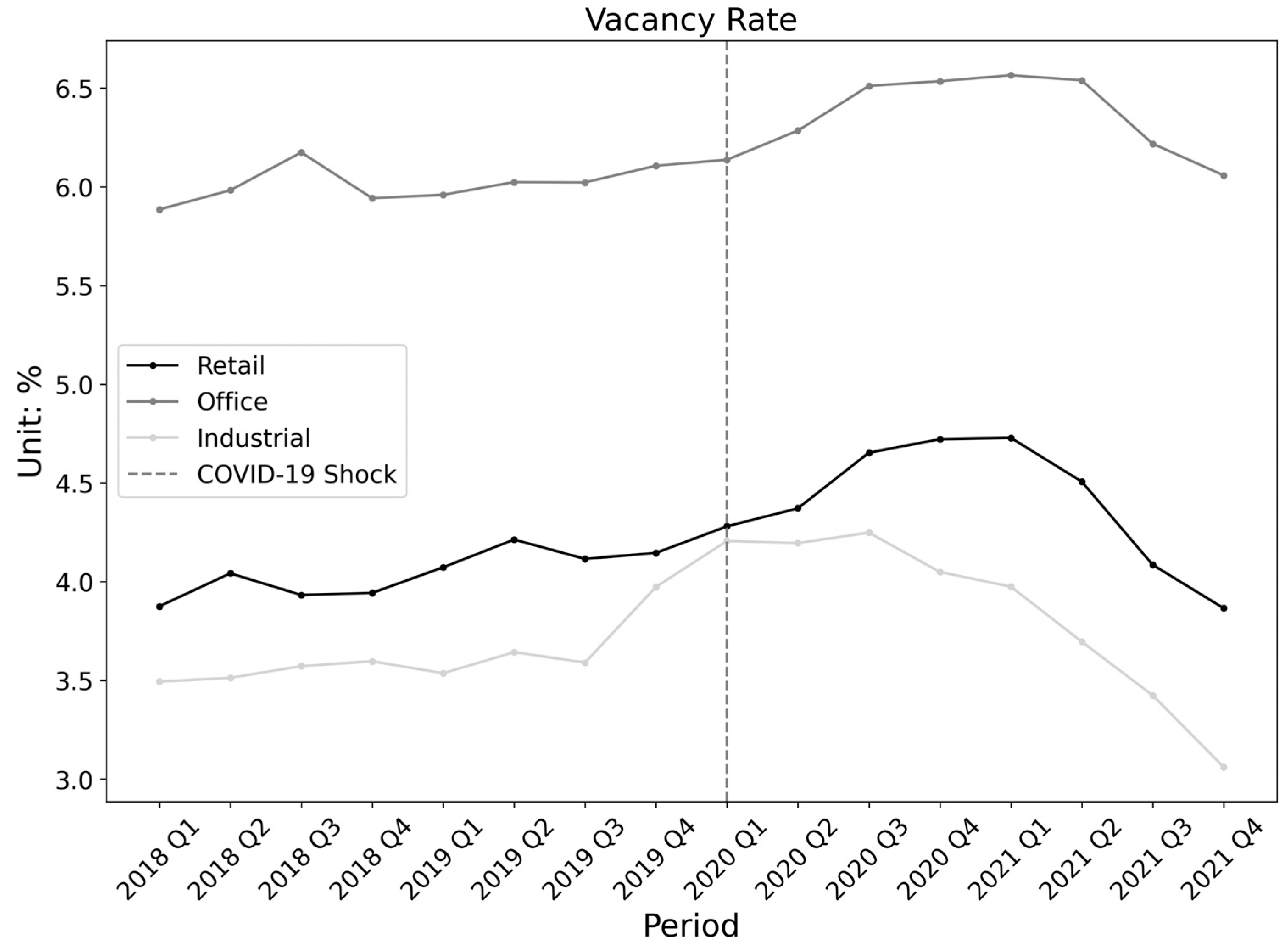

5.1. Descriptive Analysis

5.2. The Impact on Retail Properties

5.3. The Impact on Office Properties

5.4. The Impact on Industrial Properties

5.5. Robustness Check Wich COVID Shocks at Different Geographical Scale

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

8. Limitations and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| ln COVID Case in Metro Area, Current Quarter | ln COVID Case in Metro Area, Last Quarter | ln COVID death in Metro Area, Current Quarter | ln COVID Death in Metro Area, Last Quarter | ln COVID case in Florida, Current Quarter | ln COVID cases in the U.S. | ln COVID Deaths in Florida, Current Quarter | ln COVID Deaths in the U.S. | Million Employment | Percentage of Dates Requiring Facial Mask | Percentage of Dates Requiring Stay at Home | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ln COVID case in metro area, current quarter | 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.97 | 0.88 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.11 | 0.28 | 0.34 |

| ln COVID case in metro area, last quarter | 0.93 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.88 | 0.09 | 0.22 | 0.32 |

| ln COVID death in metro area, current quarter | 0.97 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.14 | 0.27 | 0.35 |

| ln COVID death in metro area, last quarter | 0.88 | 0.97 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.28 |

| ln COVID case in Florida, current quarter | 0.97 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.83 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | −0.01 | 0.23 | 0.30 |

| ln COVID cases in the U.S. | 0.96 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.82 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | −0.01 | 0.23 | 0.29 |

| ln COVID deaths in Florida, current quarter | 0.98 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.85 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 | −0.01 | 0.24 | 0.31 |

| ln COVID deaths in the U.S. | 0.96 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | −0.01 | 0.25 | 0.30 |

| Million employment | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.13 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 1.00 | 0.18 | 0.16 |

| Percentage of dates requiring facial mask | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 1.00 | 0.65 |

| Percentage of dates requiring facial mask | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.16 | 0.65 | 1.00 |

References

- Andersen, A.L.; Hansen, E.T.; Johannesen, N.; Sheridan, A. Consumer Responses to the COVID-19 Crisis: Evidence from Bank Account Transaction Data. 2020. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3609814 (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Chen, H.; Qian, W.; Wen, Q. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on consumption: Learning from high-frequency transaction data. AEA Pap. Proc. 2021, 111, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R. The Death and Life of the Central Business District; CityLab: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ramani, A.; Bloom, N. The Donut Effect of COVID-19 on Cities; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrero, J.M.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S.J. Why Working from Home Will Stick; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.; Mittal, V.; Van Nieuwerburgh, S. Work From Home and the Office Real Estate Apocalypse. 2022. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4124698 (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- Gujral, V.; Palter, R.; Sanghvi, A.; Vickery, B. Commercial Real Estate Must Do More Than Merely Adapt to Coronavirus; McKinsey: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, S.S.; Strange, W.C.; Urrego, J.A. JUE insight: Are city centers losing their appeal? Commercial real estate, urban spatial structure, and COVID-19. J. Urban Econ. 2022, 127, 103381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, D.C.; Wang, C.; Zhou, T. A first look at the impact of COVID-19 on commercial real estate prices: Asset-level evidence. Rev. Asset Pricing Stud. 2020, 10, 669–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Bai, G.; Wang, S.; Ai, M. Extraction and monitoring approach of dynamic urban commercial area using check-in data from Weibo. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 45, 508–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Li, W.; Wu, J.; Lin, J.; Chu, J.; Xia, C. How can the urban landscape affect urban vitality at the street block level? A case study of 15 metropolises in China. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2021, 48, 1245–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Z.J. The real estate risk fix: Residential insurance-linked securitization in the Florida metropolis. Environ. Plan. Econ. Space 2020, 52, 1131–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifam Marthya, K.; Major, M.D. Real estate market trends in the first new urbanist town: Seaside, Florida. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2022, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The New York Times. Coronavirus in the U.S.: Latest Map and Case Count. The New York Times. 2022. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/us/covid-cases.html (accessed on 22 May 2022).

- McCann, A. State Economies Hit the Most by Coronavirus; WalletHub: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Donihue, M.; Avramenko, A. Decomposing consumer wealth effects: Evidence on the role of real estate assets following the wealth cycle of 1990–2002. BE J. Macroecon. 2007, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Geltner, D. Commercial Real Estate and the 1990–1991 Recession in the United States. Working Paper for the Korea Development Institute. 2013, pp. 1–35. Available online: https://mitcre.mit.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Commercial_Real_Estate_and_the_1990-91_Recession_in_the_US.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2020).

- Aizenman, J.; Jinjarak, Y. Real estate valuation, current account and credit growth patterns, before and after the 2008–9 crisis. J. Int. Money Finance 2014, 48, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yunus, N. Transmission of shocks across global real estate and equity markets: An examination of the 2007–2008 housing crisis. Appl. Econ. 2018, 50, 3899–3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackworth, J. Inner-city real estate investment, gentrification, and economic recession in New York City. Environ. Plan. A 2001, 33, 863–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R. The local geographies of the financial crisis: From the housing bubble to economic recession and beyond. J. Econ. Geogr. 2011, 11, 587–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmazer, T.; Babiarz, P.; Liu, F. The impact of diminished housing wealth on health in the United States: Evidence from the Great Recession. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 130, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, H.; Song, Y.; Sohn, S.; Ahn, K. Real estate soars and financial crises: Recent stories. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, L.E.; Case, K.E. How the Commercial Real Estate Boom Undid the Banks; Conference Series; Federal Reserve Bank of Boston: Boston, MA, USA, 1992; Volume 36, pp. 57–113. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Titman, S.D.; Twite, G.J. REIT and Commercial Real Estate Returns: A Postmortem of the Financial Crisis. Real Estate Econ. 2015, 43, 8–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, S. Understanding coronanomics: The economic implications of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Dev. Areas 2021, 55, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.R.; Orsi, M.J.; Bond, E.J. Pandemic recovery analysis using the dynamic inoperability input-output model. Risk Anal. Int. J. 2009, 29, 1743–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Rogers, J.H.; Zhou, S. Global economic and financial effects of 21st century pandemics and epidemics. COVID Econ. 2020, 5, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altig, D.; Baker, S.; Barrero, J.M.; Bloom, N.; Bunn, P.; Chen, S.; Davis, S.J.; Leather, J.; Meyer, B.; Mihaylov, E. Economic uncertainty before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Public Econ. 2020, 191, 104274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrus, A.; Field, E.; Gonzalez, R. Loss in the time of cholera: Long-run impact of a disease epidemic on the urban landscape. Am. Econ. Rev. 2020, 110, 475–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.P.; Friedt, F.L.; Lautier, J.P. The impact of the Coronavirus pandemic on New York City real estate: First evidence. J. Reg. Sci. 2022, 62, 858–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Lima, W.; Lopez, L.A.; Pradhan, A. COVID-19 and Housing market effects: Evidence from US shutdown orders. Real Estate Econ. 2021, 50, 303–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francke, M.; Korevaar, M. Housing markets in a pandemic: Evidence from historical outbreaks. J. Urban Econ. 2021, 123, 103333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiren, Z.; Jieming, Z.; Yan, G. Implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for urban informal housing and planning interventions: Evidence from Singapore. Habitat Int. 2022, 127, 102627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milcheva, S. Volatility and the cross-section of real estate equity returns during COVID-19. J. Real Estate Finance Econ. 2021, 65, 293–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, D.; Thompson, A.K.; Geltner, D. Recent Drops in Market Liquidity May Foreshadow Major Drops in US Commercial Real Estate Markets; MIT Center for Real Estate Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CoStar. CoStar Commercial Real Estate Solutions; CoStar: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fuerst, F.; McAllister, P. Green noise or green value? Measuring the effects of environmental certification on office values. Real Estate Econ. 2011, 39, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geltner, D. Real estate price indices and price dynamics: An overview from an investments perspective. Annu. Rev. Financ. Econ. 2015, 7, 615–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. The U.S. Census Bureau Classification of Metropolitan Areas; U.S. Census Bureau: Suitland, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, J.; Hamilton, S.W. Risk and return in the Canadian real estate market. Can. J. Adm. Sci. Can. Sci. Adm. 1999, 16, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreal, S.; Adair, A.; Brown, L.; Webb, J. Pricing and time on the market for residential properties in a major UK city. J. Real Estate Res. 2009, 31, 209–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grashuis, J.; Skevas, T.; Segovia, M.S. Grocery shopping preferences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R.; Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Storper, M. Cities in a post-COVID world. Urban Stud. 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G. Has SARS infected the property market? Evidence from Hong Kong. J. Urban Econ. 2008, 63, 74–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, P. The Sun Belt’s Surging Office Market. Available online: https://www.commercialsearch.com/news/the-pandemic-related-acceleration-of-sun-belt-office-markets/ (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Storper, M.; Venables, A.J. Buzz: Face-to-face contact and the urban economy. J. Econ. Geogr. 2004, 4, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napiera\la, T.; Leśniewska-Napiera\la, K.; Burski, R. Impact of geographic distribution of COVID-19 cases on hotels’ performances: Case of Polish cities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, J.M.; Hochberg, Y.V. Risk perceptions and politics: Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 142, 862–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, X. COVID-19 and restaurant demand: Early effects of the pandemic and stay-at-home orders. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 3809–3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, P.K.; Phan, D.H.B.; Liu, G. COVID-19 lockdowns, stimulus packages, travel bans, and stock returns. Finance Res. Lett. 2021, 38, 101732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Chau, K.W.; Chen, Y. Impacts of information asymmetry and policy shock on rental and vacancy dynamics in retail property markets. Habitat Int. 2021, 111, 102359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The New York Times. See Reopening Plans and Mask Mandates for All 50 States. The New York Times. 2021. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/states-reopen-map-coronavirus.html (accessed on 9 August 2022).

- Zhang, D.; Zhu, P.; Ye, Y. The effects of E-commerce on the demand for commercial real estate. Cities 2016, 51, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, G.; Soebarto, V.; Zuo, J. Vacancy Visual Analytics Method: Evaluating adaptive reuse as an urban regeneration strategy through understanding vacancy. Cities 2021, 115, 103220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean | Standard Deviations | Minimum | Maximun | Number Of Observations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Office | Market Rent Growth | 0.0081 | 0.0074 | −0.0157 | 0.0290 | 384 |

| Vacancy Rate | 0.0618 | 0.0212 | 0.0123 | 0.1178 | 384 | |

| Sales Volume Transactions | 44.6204 | 44.8145 | 1.0000 | 255.0000 | 382 | |

| Market Sale Price Growth | 0.0330 | 0.0156 | −0.0081 | 0.0967 | 384 | |

| Retail | Market Rent Growth | 0.0072 | 0.0046 | −0.0079 | 0.0307 | 384 |

| Vacancy Rate | 0.0422 | 0.0115 | 0.0131 | 0.0781 | 384 | |

| Sales Volume Transactions | 56.2057 | 52.2201 | 1.0000 | 287.0000 | 384 | |

| Market Sale Price Growth | 0.0306 | 0.0204 | −0.0285 | 0.0940 | 384 | |

| Industrial | Market Rent Growth | 0.0159 | 0.0066 | 0.0056 | 0.0526 | 384 |

| Vacancy Rate | 0.0374 | 0.0166 | 0.0002 | 0.0938 | 384 | |

| Sales Volume Transactions | 38.0079 | 42.5893 | 1.0000 | 190.0000 | 378 | |

| Market Sale Price Growth | 0.0914 | 0.0183 | 0.0334 | 0.1715 | 384 | |

| ln COVID case, current quarter | 4.29 | 4.56 | 0.00 | 12.16 | 384 | |

| ln COVID death, current quarter | 2.34 | 2.69 | 0.00 | 7.80 | 384 | |

| Million employment | 0.36 | 0.40 | 0.02 | 1.42 | 384 | |

| Percentage of staying at home | 4.94 | 21.10 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 384 | |

| Percentage of wearing facial mask | 6.54 | 23.25 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 384 | |

| Market Rent Growth | Vacancy Rate | Market Sale Price Growth | Sales Volume Transactions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ln COVID case in metro area, current quarter | −0.000110 (0.000102) | 0.000319 * (0.000138) | 0.000307 (0.000464) | −0.903 * (0.376) | ||||

| ln COVID case in metro area, last quarter | 0.000600 *** (0.000111) | 0.0000342 (0.000130) | 0.00136 * (0.000618) | 2.387 *** (0.477) | ||||

| ln COVID death in metro area, current quarter | 0.000125 (0.000144) | 0.000507 * (0.000244) | 0.00153 (0.000796) | −2.694 *** (0.577) | ||||

| ln COVID death in metro area, last quarter | 0.000729 *** (0.000115) | 0.0000551 (0.000208) | 0.00127 (0.00103) | 5.372 *** (0.901) | ||||

| Million Employment | 0.0530 *** (0.00819) | 0.0500 *** (0.00810) | −0.000676 (0.0157) | 0.00103 (0.0154) | 0.187 * (0.0835) | 0.187 * (0.0874) | 135.6 (110.9) | 97.04 (106.3) |

| Percentage of dates requiring facial mask | −0.0000497 *** (0.00000904) | −0.0000510 *** (0.00000917) | 0.0000212 (0.0000135) | 0.0000225 (0.0000132) | −0.00000402 (0.0000578) | −0.00000299 (0.0000598) | 0.000205 (0.0876) | −0.0141 (0.0879) |

| Percentage of dates requiring stay at home | −0.0000229 (0.0000125) | −0.0000207 (0.0000137) | 0.0000109 (0.0000234) | 0.0000138 (0.0000247) | −0.0000273 (0.0000732) | −0.0000233 (0.0000737) | −0.245 * (0.0993) | −0.203 (0.102) |

| Q2 | 0.00187 *** (0.000241) | 0.00221 *** (0.000212) | 0.000101 (0.000649) | 0.0000124 (0.000636) | 0.000884 (0.000888) | 0.00150 * (0.000684) | 4.221 (2.069) | 5.682 ** (1.996) |

| Q3 | 0.00157 *** (0.000295) | 0.00166 *** (0.000339) | −0.00121 * (0.000431) | −0.00143 ** (0.000394) | 0.000932 (0.000869) | 0.000593 (0.000916) | 8.495 *** (2.186) | 10.19 *** (2.207) |

| Q4 | 0.000659 (0.000387) | 0.000783 (0.000391) | −0.00142 ** (0.000502) | −0.00162 ** (0.000498) | 0.00220 (0.00134) | 0.00237 (0.00125) | 10.72 ** (2.922) | 10.11 *** (2.491) |

| constant | −0.0140 *** (0.00296) | −0.0131 *** (0.00297) | 0.0414 *** (0.00599) | 0.0411 *** (0.00586) | −0.0434 (0.0302) | −0.0432 (0.0316) | −1.878 (39.74) | 11.72 (38.01) |

| Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| R-squared | 0.427 | 0.426 | 0.106 | 0.0971 | 0.228 | 0.218 | 0.297 | 0.339 |

| F Statistics | 54.51 | 106.3 | 5.411 | 6.224 | 11.61 | 11.65 | 9.161 | 13.45 |

| Number of Observations | 384 | 384 | 384 | 384 | 384 | 384 | 384 | 384 |

| Market Rent Growth | Vacancy Rate | Market Sale Price Growth | Sales Volume Transactions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ln COVID case in metro area, current quarter | −0.000765 ** (0.000226) | 0.000215 (0.000208) | 0.000682 (0.000574) | 0.334 (0.829) | ||||

| ln COVID case in metro area, last quarter | 0.000527 * (0.000232) | 0.000215 (0.000219) | 0.000112 (0.000485) | 0.805 (0.804) | ||||

| ln COVID death in metro area, current quarter | −0.00133 *** (0.000251) | 0.0000574 (0.000350) | 0.00125 (0.000816) | −1.190 (0.859) | ||||

| ln COVID death in metro area, last quarter | 0.000998 *** (0.000226) | 0.000705 (0.000382) | 0.000102 (0.000663) | 3.213 ** (0.962) | ||||

| Million Employment | 0.00928 (0.00912) | −0.00159 (0.0108) | −0.0653 * (0.0264) | −0.0676 * (0.0262) | 0.135 ** (0.0414) | 0.141 ** (0.0414) | 198.4 (123.4) | 178.7 (127.6) |

| Percentage of dates requiring facial mask | −0.0000119 (0.0000210) | −0.0000165 (0.0000215) | 0.00000750 (0.0000244) | 0.00000572 (0.0000236) | −0.0000726 (0.0000471) | −0.0000714 (0.0000474) | −0.00224 (0.0365) | −0.0105 (0.0360) |

| Percentage of dates requiring stay at home | −0.0000427 (0.0000227) | −0.0000405 (0.0000226) | −0.0000259 (0.0000225) | −0.0000169 (0.0000233) | −0.0000337 (0.0000632) | −0.0000289 (0.0000645) | −0.167 (0.0849) | −0.128 (0.0827) |

| Q2 | 0.000451 (0.00112) | 0.000968 (0.00104) | 0.00000228 (0.000596) | 0.0000252 (0.000565) | 0.00349 *** (0.000794) | 0.00332 *** (0.000641) | 6.899 * (2.692) | 7.108 * (2.720) |

| Q3 | 0.00121 (0.000889) | 0.00195 * (0.000878) | 0.000304 (0.000686) | 0.000283 (0.000734) | 0.00425 *** (0.000874) | 0.00367 *** (0.000795) | 5.361 *** (1.418) | 5.915 ** (1.603) |

| Q4 | −0.00143 (0.000877) | −0.00108 (0.000749) | −0.000367 (0.000971) | −0.000775 (0.000910) | 0.00684 *** (0.00151) | 0.00638 *** (0.00117) | 6.346 ** (2.215) | 4.837 * (2.103) |

| constant | 0.00630 (0.00329) | 0.00958 * (0.00392) | 0.0835 *** (0.00972) | 0.0846 *** (0.00966) | −0.0216 (0.0153) | −0.0233 (0.0154) | −34.83 (44.45) | −26.92 (45.52) |

| Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| R-squared | 0.101 | 0.0987 | 0.0952 | 0.0996 | 0.153 | 0.151 | 0.210 | 0.235 |

| F Statistics | 7.209 | 6.507 | 4.523 | 5.100 | 17.46 | 12.37 | 11.21 | 15.10 |

| Number of Observations | 384 | 384 | 384 | 384 | 384 | 384 | 382 | 382 |

| Market Rent Growth | Vacancy Rate | Market Sale Price Growth | Sales Volume Transactions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ln COVID case in metro area, current quarter | −0.000354 (0.000181) | 0.000839 ** (0.000271) | 0.000735 * (0.000323) | 0.0822 (0.256) | ||||

| ln COVID case in metro area, last quarter | 0.00123 *** (0.000188) | −0.000829 * (0.000310) | 0.00121 ** (0.000379) | 0.493 (0.296) | ||||

| ln COVID death in metro area, current quarter | −0.000270 (0.000174) | 0.00111 * (0.000432) | 0.00158 * (0.000622) | −1.741 * (0.646) | ||||

| ln COVID death in metro area, last quarter | 0.00182 *** (0.000167) | −0.00113 * (0.000455) | 0.00173 ** (0.000511) | 2.724 ** (0.815) | ||||

| Million Employment | 0.0171 (0.0101) | 0.00687 (0.0109) | −0.0335 (0.0333) | −0.0218 (0.0328) | 0.0533 (0.0586) | 0.0526 (0.0582) | 189.5 * (79.58) | 167.7 * (78.45) |

| Percentage of dates requiring facial mask | −0.0000903 *** (0.0000131) | −0.0000943 *** (0.0000138) | 0.0000634 * (0.0000247) | 0.0000668 * (0.0000267) | −0.000136 *** (0.0000343) | −0.000137 ** (0.0000364) | 0.0290 (0.0402) | 0.0228 (0.0389) |

| Percentage of dates requiring stay at home | −0.0000197 (0.0000177) | −0.0000112 (0.0000199) | 0.00000403 (0.0000458) | 0.00000391 (0.0000485) | −0.000106 (0.0000517) | −0.0000903 (0.0000563) | −0.141 * (0.0590) | −0.107 (0.0562) |

| Q2 | 0.000453 * (0.000201) | 0.00120 *** (0.000205) | −0.000332 (0.000754) | −0.00104 (0.000784) | 0.00261 ** (0.000804) | 0.00297 *** (0.000724) | 2.422 * (0.881) | 2.607 ** (0.787) |

| Q3 | 0.00233 *** (0.000316) | 0.00274 *** (0.000322) | −0.00150 (0.00105) | −0.00225 (0.00117) | 0.00581 *** (0.000957) | 0.00533 *** (0.000839) | 1.421 (1.137) | 2.213 * (1.059) |

| Q4 | 0.00331 *** (0.000397) | 0.00347 *** (0.000320) | −0.000799 (0.00124) | −0.00140 (0.00116) | 0.00866 *** (0.00119) | 0.00811 *** (0.00108) | 5.620 * (2.221) | 4.405 * (1.986) |

| constant | 0.00592 (0.00360) | 0.00927 * (0.00398) | 0.0490 *** (0.0125) | 0.0455 ** (0.0122) | 0.0618 ** (0.0210) | 0.0627 ** (0.0211) | −34.67 (28.95) | −26.02 (28.57) |

| R-squared | 0.488 | 0.503 | 0.0666 | 0.0612 | 0.372 | 0.366 | 0.201 | 0.232 |

| Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| F Statistics | 90.12 | 86.95 | 4.920 | 4.855 | 23.75 | 23.31 | 4.958 | 4.487 |

| Number of Observations | 384 | 384 | 384 | 384 | 384 | 384 | 378 | 378 |

| Market Rent Growth | Vacancy Rate | Market Sale Price Growth | Sales Volume Transactions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retail property market | ||||||||

| ln COVID case in metro area, current quarter | −0.0000178 (0.00020) | −0.000324 (0.00079) | 0.000112 (0.00133) | 1.097 (0.925) | ||||

| ln COVID case in metro area, last quarter | 0.000597 *** (0.00010) | 0.0000559 (0.00015) | 0.00137 * (0.00062) | 2.319 *** (0.367) | ||||

| ln COVID death in metro area, current quarter | 0.000163 (0.00024) | −0.000526 (0.00070) | 0.000458 (0.00126) | −2.740 ** (0.922) | ||||

| ln COVID death in metro area, last quarter | 0.000725 *** (0.00012) | 0.000156 (0.00024) | 0.00138 (0.00100) | 5.376 *** (0.897) | ||||

| ln COVID case in Florida, current quarter | −0.0000635 (0.00011) | −0.000015 (0.00006) | 0.000441 (0.00059) | 0.000401 (0.00031) | 0.000134 (0.00106) | 0.000416 (0.00062) | −1.373 * (0.631) | 0.018 (0.275) |

| Office property market | ||||||||

| ln COVID case in metro area, current quarter | 0.000507 (0.00035) | 0.00186 * (0.00083) | −0.000738 (0.00095) | 2.39 (1.785) | ||||

| ln COVID case in metro area, last quarter | 0.000484 ** (0.00017) | 0.00016 (0.00028) | 0.000159 (0.00044) | 0.741 (0.835) | ||||

| ln COVID death in metro area, current quarter | 0.000215 (0.00051) | 0.000659 (0.00053) | −0.000263 (0.00098) | −1.858 * (0.742) | ||||

| ln COVID death in metro area, last quarter | 0.000848 ** (0.00023) | 0.000646 (0.00036) | 0.000249 (0.00064) | 3.277 ** (0.927) | ||||

| ln COVID case in Florida, current quarter | −0.000873 *** (0.00021) | −0.000599 *** (0.00015) | −0.00113 * (0.00054) | −0.000234 (0.00027) | 0.000975 (0.00054) | 0.000586 (0.00030) | −1.416 (0.820) | 0.26 (0.328) |

| Industrial property market | ||||||||

| ln COVID case in metro area, current quarter | −0.00031 (0.00045) | 0.000692 (0.00065) | 0.00138 (0.00121) | 0.808 (0.50000) | ||||

| ln COVID case in metro area, last quarter | 0.00123 *** (0.00019) | −0.000824 * (0.00031) | 0.00119 ** (0.00035) | 0.468 (0.30900) | ||||

| ln COVID death in metro area, current quarter | −0.000342 (0.00033) | 0.000522 (0.00084) | 0.000514 (0.00105) | −3.494 * (1.32200) | ||||

| ln COVID death in metro area, last quarter | 0.00183 *** (0.00017) | −0.00107 * (0.00045) | 0.00183 ** (0.00050) | 2.892 ** (0.88900) | ||||

| ln COVID case in Florida, current quarter | −0.0000302 (0.00023) | 0.0000281 (0.00009) | 0.000101 (0.00041) | 0.000228 (0.00031) | −0.00044 (0.00079) | 0.000414 (0.00035) | −0.5 (0.27600) | 0.685 * (0.31100) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wen, Y.; Fang, L.; Li, Q. Commercial Real Estate Market at a Crossroads: The Impact of COVID-19 and the Implications to Future Cities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12851. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912851

Wen Y, Fang L, Li Q. Commercial Real Estate Market at a Crossroads: The Impact of COVID-19 and the Implications to Future Cities. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):12851. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912851

Chicago/Turabian StyleWen, Yijia, Li Fang, and Qing Li. 2022. "Commercial Real Estate Market at a Crossroads: The Impact of COVID-19 and the Implications to Future Cities" Sustainability 14, no. 19: 12851. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912851

APA StyleWen, Y., Fang, L., & Li, Q. (2022). Commercial Real Estate Market at a Crossroads: The Impact of COVID-19 and the Implications to Future Cities. Sustainability, 14(19), 12851. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912851