1. Introduction

Solidarity in social life is a vanishing value. However, in situations of danger, weakening or illness, the existing system of social networks allows members of society to survive a period of emergency. A similar situation applied to the socio-economic abruptness caused by COVID-19 [

1,

2]. The most difficult one for many families was the loss of a loved one. Some modes of financial support at such times are the funeral allowances and survivor pensions paid.

Without referring to the real amount of benefits, the Polish social security system can be assessed as one of the better developed in Europe, although at the same time, very complicated. This is judged by the risks covered by the system. For historical reasons, in the Polish model, the main source of social insurance rights and the system in many elements is of an insurance nature, i.e., it requires a contribution cost to be paid in advance, as well as the fulfilment of additional conditions, such as the minimum contribution period, etc. [

3] As the final stage of the abolition of open pension funds (OFEs) is approaching, the Polish old-age pension system will once again be an entirely pay-as-you-go system (PAYG) with an intergenerational contract. Thus, social security is a way of sharing current production between those who work and those who benefit [

4]. Additionally, although individualism is retained in the old-age pension calculation methodology (the amount of the pension depends on the contributions collected), the sustainability of the system depends on the economic base and thus, among other things, “on the possibility of obtaining contributions in the area of the defined insurance community, the imputation of which in a given financial year depends on real relations” [

5]. While old age pensions are becoming increasingly dependent on individual contributions—disability pensions followed by survivor pensions, remain solidarity benefits. As the right to receive them applies after 5 years of contributions, their amount depends on past salaries, the base value of wages in the economy and is covered by the contributions of all insured persons.

The core institution in the Polish social security system is the Social Insurance Institution (ZUS). It operates the Social Insurance Fund (FUS) within which there are separate sub-funds [

6]:

Old-age pension fund—the fund is financed by contributions from employees and employers as well as subsidies from the budget; benefits are paid from this fund to offset the risk of old age, i.e., the difficulty of earning an income due to reduced psychological and physical capacity resulting from age;

The disability fund covers, among others, disability pensions as well as benefits related to the risk of death of the breadwinner (survivor pension);

Sickness fund—fed by the contributions of the insured only with subsidies from the state budget; the fund finances benefits related to loss of income as a result of illness (temporary inability to work) and benefits resulting from the risk of maternity (maternity leave, paternity leave). It should be noted that the sickness fund is not a source of funding for the costs of medical services (doctor’s visit, surgery, reimbursable medicines)—this is financed by health insurance which is not a separate insurance system;

Accident fund—financed solely by the employer’s contributions, covering various types of benefits arising from the risk of accident at work and occupational disease, including benefits related to sick leave, rehabilitation, inability to continue working, benefits to the family of a worker who has died as a result of an accident or occupational disease.

Benefits paid by the Social Insurance Institution (ZUS), including from the social insurance system, are presented in

Table 1. Not all of them are of an insurance nature, i.e., they are financed from contributions to the four funds mentioned above. Some are financed by subsidies from the state budget (e.g., funeral benefits, veteran’s allowances), some from the Labour Fund (pre-retirement benefits).

The benefits analysed in the article, although financed from a single fund, are based on different eligibility criteria. Funeral allowance is not only available to the family of the deceased, but often also to neighbors, friends or institutions, i.e., all those who have actually covered the costs of burying the deceased person. However, it is not a benefit that is paid on every death as benefit in cash—the deceased person or their loved one must be covered by some kind of social security title, even a non-contributional one. The value of the allowance is fixed and as of 2011 amounts to PLN 4000 (about EUR 900).

In turn, the condition for the award of a survivor pension from a deceased person is that he or she was entitled to an old-age pension or a disability pension, before his or her death, or this person should have been fully-filed to meet the conditions required for obtaining one of those benefits. In general, the deceased must have been covered by social security. The catalogue of persons entitled to a survivor pension is very narrow. These include children (own or adopted) up to the end of their schooling, a spouse (in a very few cases), grandchildren and siblings (if supported by the deceased). The amount of the survivor pension is a direct derivative of the method of calculating the disability pension, and it, again, is directly related to the old-age pension calculation rules. In the following sections, we will discuss the most important issues affecting the (under)development of the survivor pension system in Poland [

7].

For the first time, the old-age pension and disability pension (including survivor benefit) were distinguished in 1954. The level of pension and other benefits based on it became partly dependent on wage level. The minimum eligibility insurance period for disability pension was equal to 5 years, and for the old-age pension, 15 years. At the beginning of economic regime transformation in 1989, the disability pension system was universal, with very moderate eligibility criteria and low cash benefits. In the first few years, it served as a de facto protection against unemployment and a channel for the transfer of social support [

8,

9]. In 1997, reform of disability assessment was initiated. The definition became more economic and now, it is concerning the ability to work. The revolutionary old-age pension reform introduced in 1999 forced the allocation of the disability pensions into a separate financial pool—the Disability Fund. This made it evident that the cost of the disability pension was not much lower than the old-age pension, and that developed benefits in kind and additional privileges for the disabled made this even more costly. The effect of using a disability system as a buffer for economic transformation was the number of disability pension’s beneficiaries nearly equal to old-age pensioners. Since then, there were no systemic changes or reduction of services and kinds of benefits granted, but the administrators’ activity focused on expense reductions [

9].

With the introduction of the new principles of the social insurance system construction in Poland, i.e., as of 1 January 1999, the disability insurance contribution had been gradually reduced from 13 to 6.0 percent of the assessment basis in 2008. This resulted in a renewed increase in the deficit of the disability fund. For this reason, among others, as of 1 February 2012, the disability insurance contribution rate was raised again to 8.0%. From 1 December 2017, the Act [

10] entered into force, which stipulated that the right to an incapacity pension is granted only to a person who does not have an established right to an old-age pension. This regulation was the driving force behind a further decline in the number of people receiving pensions financed from the disability fund, as it shifts the burden of payments to the pension fund.

In following years, the access criteria were narrowed, the assessment committees were stricter, with the consequence that the number of people receiving pensions has halved in the last decade (

Table 2). However, all these changes did not apply to survivor pensions. The rules for awarding them have remained unchanged since the 1950s, making the essential benefit of family policy dependent on disability policy. While just a decade ago, the number of people receiving disability pensions and survivor benefits was similar, at the end of 2021, family members’ benefit was paid to twice as many people as the disability pension and more than that, it accounts for almost 70% of the value of the disability fund.

One of the components through which the performance of the disability fund can be assessed is its financial balance [

11]. The disability fund has been recording surpluses of contributions’ income over pay-outs since 2018. This trend continues in 2020 and 2021 as well. In the explanations provided by ZUS, it was pointed out that the good financial condition is largely due to revenues from foreigners working in Poland (mainly from Ukraine), who pay contributions and, for the most part, have not yet qualified for benefits. It was the publication of the results of the disability fund for 2021 that encouraged the authors to ask the research question: Does the surplus in the fund mean that the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent high wave of deaths left the fund’s situation unaffected? While in the case of the disability benefit it can take more than a year from the illness to the award of the benefit, in the case of the analysed benefits, payment is made almost immediately after the death of the insured. For funeral allowance, this is generally 7–14 days, for survivor pension, around 1–3 months. There is a perception in the public domain of significant increases in public health expenditure, the highest number of deaths since the Second World War, resulting not only from COVID-19 but also limited access to health care during the lockdown. The disability fund pays benefits as a direct consequence of the death of the insured—will social costs than also increase with the pandemic? The study will therefore confront the impact of the increase in deaths on the number of survivor pensions and funeral allowance.

Although the Polish social security system has been analysed by many researchers (J. Auleytner [

12], Golinowska [

13,

14], M. Rymsza [

15], R. Szarfenberg [

16] and M. Góra [

17]), isolated research on the disability fund is marginal. The few works include publications by W. Nagel [

18], W. Błoch [

19] and D. Dzienisiuk [

20]. Polish research mostly focuses on the pension system, leaving the disability fund in the domain of disability policy research. However, ongoing economic, social and demographic changes mean that the disability fund functions less as the main source of security for people with disabilities and increasingly influences family policy. This study addresses, for the first time, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the operation of the disability fund, i.e., the number of death and survivor benefits paid out, taking into account changes in the structure of benefits paid out from the fund. Therefore, the aim of this article is to verify the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the situation of the disability fund in Poland. The study considers the impact of deaths on the number of survivor and funeral benefits paid. We selected benefits which are a direct consequence of the death of the insured person and do not involve a medical assessment or subsequent steps in the insurance procedure as is the case, for example, for incapacity benefits.

2. Methodology

Four years were included in the study: 2018 and 2019 as pre-pandemic years and 2020 and 2021 as pandemic years. For the presentation of changes in the structure of the disability fund, data for the years 2011–2021 are also presented. The data from publications of the Polish Social Insurance Institution, the Central Statistical Office in Warsaw and the Polish Ministry of Health were used. In order to check whether the COVID-19 pandemic had an impact on the number of benefits from the disability fund, an analysis of the number of death and survivor pensions was carried out. Dynamic analysis and basic statistics were used. The total number of deaths and deaths caused by COVID-19 were also analysed comparatively. In addition, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were determined between the total number of deaths and deaths due to COVID-19 and the number of funeral allowance and survivor pensions awarded.

The analysis of the dynamics was restricted to the determination of single-basis indices according to the formula:

where:

—value of the phenomenon in the selected period,

—the value of the phenomenon in the base period.

This makes it possible to determine by how much percentage the value of the analysed phenomenon changed in comparison to the base period (the so-called base).

The group of basic statistics included: the arithmetic mean determined from the formula:

where:

—number of observations,

—value of the phenomenon in particular periods,

maximum and minimum value and median determined from the formula:

The first version of the formula is used when n is an even number, the second version is used when it is an odd number. It is necessary here to use a non-decreasingly ordered series.

Correlation is a measure of a monotonic relationship between two variables. A monotonic relationship between two variables occurs when either as the value of the first variable increases, the value of the second variable increases, or as the value of the first variable increases, the value of the second variable decreases [

21].

The Pearson linear correlation coefficient is determined from the formula:

where:

, —arithmetic mean of the variables for which the correlation coefficient is determined,

, —successive values of the variables for which the correlation coefficient is determined.

The Pearson correlation coefficient takes values in the range of .

When interpreting the results, the classification according to J. Guilford was used, where [

22]:

|r|= 0—lack of correlation,

0.0 < |r| ≤ 0.1—dim correlation,

0.1 < |r| ≤ 0.3—weak correlation,

0.3 < |r| ≤ 0.5—average correlation,

0.5 < |r| ≤ 0.7—high correlation,

0.7 < |r| ≤ 0.9—very high correlation,

0.9 < |r| < 1.0—almost full correlation,

|r| = 1—full correlation.

3. Results

The research began with an analysis of the number of funeral allowance collected.

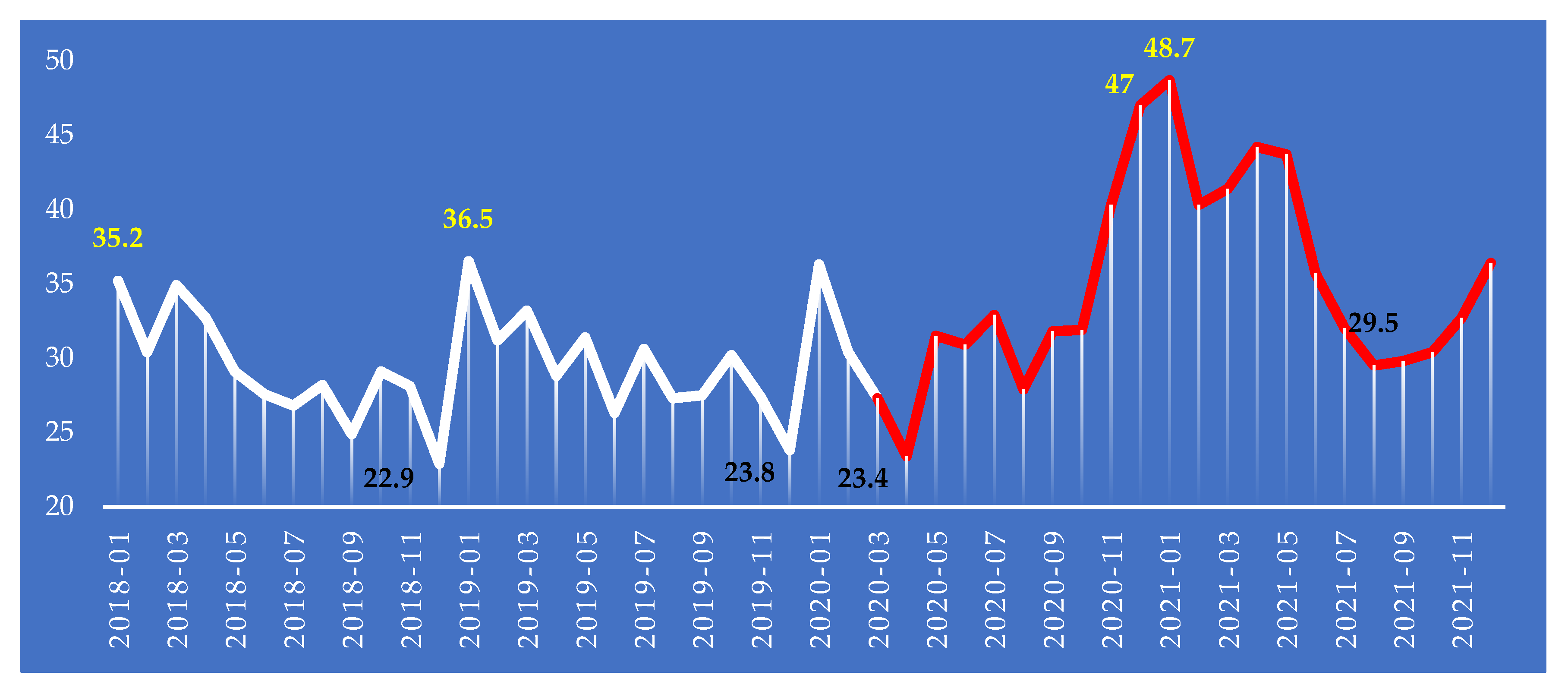

Figure 1 shows the development of the number of funeral allowance collected from 2018 to 2021 on a monthly basis. The red colour indicates the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic and its dormant periods. The maximum (yellow) and minimum (black) values recorded in the following years are also marked (

Table 3).

The average number of people drawing a funeral allowance increased significantly in 2020 and 2021. Compared to 2018, these were increases of 11.90% and 27.13%, respectively, while compared to 2019, the increases were 10.54% and 25.58%, respectively. The maximum number of people who received benefits also increased. In 2020, this was 47,000 people (December), while in the following year, it was 48,700 people (January). As can be seen in

Figure 1, a decisive increase can be seen at the end of 2020/2021, with a much lower number of benefits drawn in the summer of 2021 (a minimum of 29.5 in August 2021) and further increases in the fourth quarter of 2021. The median number of death benefits collected is also significantly higher in 2020 and 2021 (

Table 3). All indications are that the number of funeral benefits are linked to successive waves of COVID-19-related illnesses and deaths.

The above patterns are also confirmed when analysing the dynamics (

Figure 2). Changes are illustrated by comparing the pandemic years 2020–2021 with the same two-year preceding period (2018–2019). For 2018 and 2019, the volumes of the number of benefits in 2020 and 2021 were compared sequentially. Assuming that the first recorded death resulting from the COVID-19 disease in Poland occurred on 14 March 2020, and the number of deaths gradually increased, from June 2020 and 2021, the number of funeral allowance paid was significantly higher than in previous years. The largest increases were recorded in December 2020 and 2021.

The next step is to analyse the number of benefit recipients receiving a survivor pension.

Figure 3 shows the evolution of the number of survivor pension recipients from 2018 to 2021 on a monthly basis. The red colour indicates the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic and its dormant periods. The maximum (yellow) and minimum (black) values recorded in the following years are also marked (

Table 4).

The average number of people drawing a survivor pension decreased in 2020 and 2021. Compared to 2018, these were decreases of 1.73% and 2.78%, respectively, while compared to 2019, the decreases were 0.92% and 1.47%, respectively. The maximum number of people drawing a survivor pension also fell. The highest numbers of people drawing survivor pensions in 2018–2020 were in January, while in 2021, they were in July and August. The lowest numbers of people claiming this benefit, throughout the period under review, were recorded in October. This may be due to the fact that in September and October, entitled persons are required to submit documents confirming the continuation of their education. In the absence of such documents, the benefit lapses. The median number of recipients of the survivor pension is also decreasing year on year (

Table 4).

The above patterns are also confirmed when analysing the dynamics (

Figure 4). Changes are illustrated by comparing the pandemic years 2020–2021 with the same two-year preceding period (2018–2019). For 2018 and 2019, the figures for the number of recipients receiving a survivor pension in 2020 and 2021 are compared sequentially.

The next stage of the study is to analyse the total number of deaths.

Figure 5 shows the evolution of the total number of deaths from 2018 to 2021 on a monthly basis. The red colour indicates the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic and its dormant periods. The maximum (yellow) and minimum (black) values recorded in the following years are also marked (

Table 5).

The average number of deaths increased significantly in 2020 and 2021. Compared to 2018, these were increases of 18.06% and 26.11%, respectively, while compared to 2019, the increases were 19.13% and 27.25%, respectively. The maximum number of deaths has also increased. In 2020, it was 60,515 (November), while the following year, there was a decrease in the maximum number of deaths to 57,630 (December). Despite this decrease, the number of deaths was much higher than in 2018–2019. As can be seen in

Figure 5, a definite increase can be seen at the end of 2020 and 2021, while the summer period saw the lowest numbers of deaths. The median total number of deaths is also significantly higher in 2020 and 2021 (

Table 5). All indications are that the higher number of deaths is due to the COVID-19 pandemic (

Figure 6).

Figure 6 shows the number of deaths due to COVID-19. Both deaths due to COVID-19 without comorbidities and deaths due to COVID-19 and comorbidities were considered (data on deaths announced by the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Poland).

The above patterns are also confirmed when analysing the dynamics (

Figure 7). Changes are illustrated by comparing the pandemic years 2020–2021 with the same two-year preceding period (2018–2019). For 2018 and 2019, the volumes of the total number of deaths in 2020 and 2021 are compared sequentially. A clear increase in the total number of deaths, compared to previous years, is evident.

The final stage of the study is a brief analysis presented in

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 showing scatter plots and correlation coefficient values between variables. All determined correlation coefficients are statistically significant (

p < 0.05).

The relationship between the total number of deaths and the number of funeral allowance is characterised by a high correlation with a positive direction (r = 0.5887). This means that as the total number of deaths increases, the number of funeral allowances granted increases.

The relationship between the total number of deaths and the number of survivor pensions awarded is also characterised by a high correlation. However, in this case, the correlation has a negative direction (). This means that as the total number of deaths increases, the number of survivor pensions awarded decreases. As mentioned earlier, these pensions are predominantly granted after the death of a parent to underage and studying children. It can therefore be inferred that it is predominantly elderly people with no minor offspring who die.

The relationship between the number of COVID-19 deaths and the number of funeral allowance is characterised by a very high correlation with a positive direction (). This means that as the number of deaths due to COVID-19 increases, the number of funeral allowance granted increases.

The relationship between the number of COVID-19 deaths and the number of recipients of survivor pensions is characterised by an average correlation with a negative direction (). This means that as the number of deaths increases, the number of survivor pension recipients decreases. Similarly, as with the total number of deaths, this indicates a higher mortality rate among elderly people with no dependents and education.

4. Conclusions

Research into the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on socio-economic phenomena began almost as quickly as the pandemic itself. First and foremost, they concerned the impact on the income potential of households dependent on social security benefits [

23]. The first study (published in August 2022) on the impact of COVID-19 on the disability pension system focused rather on the reduction in accessibility to the system [

24]. The findings presented indicated the difficulty in capturing the time gap between actual illnesses and claims made or benefits awarded. The study presented here, due to the selection of benefits, is devoid of these biases. For this study, we have chosen benefits which are a direct consequence of the insured’s death and do not involve a medical assessment or subsequent steps within the insurance procedure as is the case, for example, for disability benefits.

The results obtained should be assessed as inconclusive. In the case of funeral allowances, an increase in the number of deaths translates directly into an increase in the number of allowances paid. However, the results of the research indicate that, despite the very broad inclusion of those entitled to receive the benefit, in many cases, it is not paid. This may apply to homeless people or those who, as a result of emigration, fell out of the social support system after returning to the country. Taking into account the practice of the Polish funeral market, this is probably not due to a lack of knowledge or activity on the part of the beneficiaries, as Polish funeral houses can act on behalf of the beneficiaries and commonly do so.

The results obtained from the study of survivor pensions also raise a number of further questions. Assuming that the increase in the number of deaths mainly concerned older age cohorts, the increase in the percentage of deaths also included the 40+ age group, i.e., the group where children become entitled in the event of the death of a parent. In addition, for the elderly, one would expect entitlement to be acquired by spouses or close family members (siblings, grandchildren). Research has not shown such a trend. So where can we see the reasons for the decline in survivor pensions despite the increase in deaths? This is all the more surprising as the award of survivor pensions is not discretionary, but is granted on the basis of the insured’s documented service record. Sometimes, however, such documentation is difficult to collect, especially if it relates to the period before the introduction of the IT systems. Moreover, in the 1990s and the first decade of the current century, many people were not insured due to lack of work or undeclared work. Thus, it may happen that eligible persons are not able to show 5 years of insurance coverage. Another factor is the low fertility rate of families—about 25% of families in Poland have no children. The change in the family model also means that there are fewer and fewer situations in which the spouse remains economically inactive and the survivor pension may be the only source of income. Nevertheless, the research presented in this article confirms that there is no impact of the increased number of deaths on the increase in the number of survivor pensions and therefore, there is no negative impact of the COVID-19 implications on the disability fund. That should be, however, seen as the first stage of a long-term research into the changes in the social insurance system caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The results presented can also contribute to the discussion on the legitimacy of maintaining survivor pensions in their current form and financing them through the disability fund and the methodological link to disability pensions. At the heart of the discussion, however, is the question of a paradigm shift based on maintenance obligations and a new definition of social solidarity. Survivor pensions are an example of one of the few benefits where this solidarity still applies.