Urban Soundscapes in the Imaginaries of Native Digital Users: Guidelines for Soundscape Design

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Background

2.1.1. Projective Techniques

2.1.2. Semiotic Analysis of Narratives

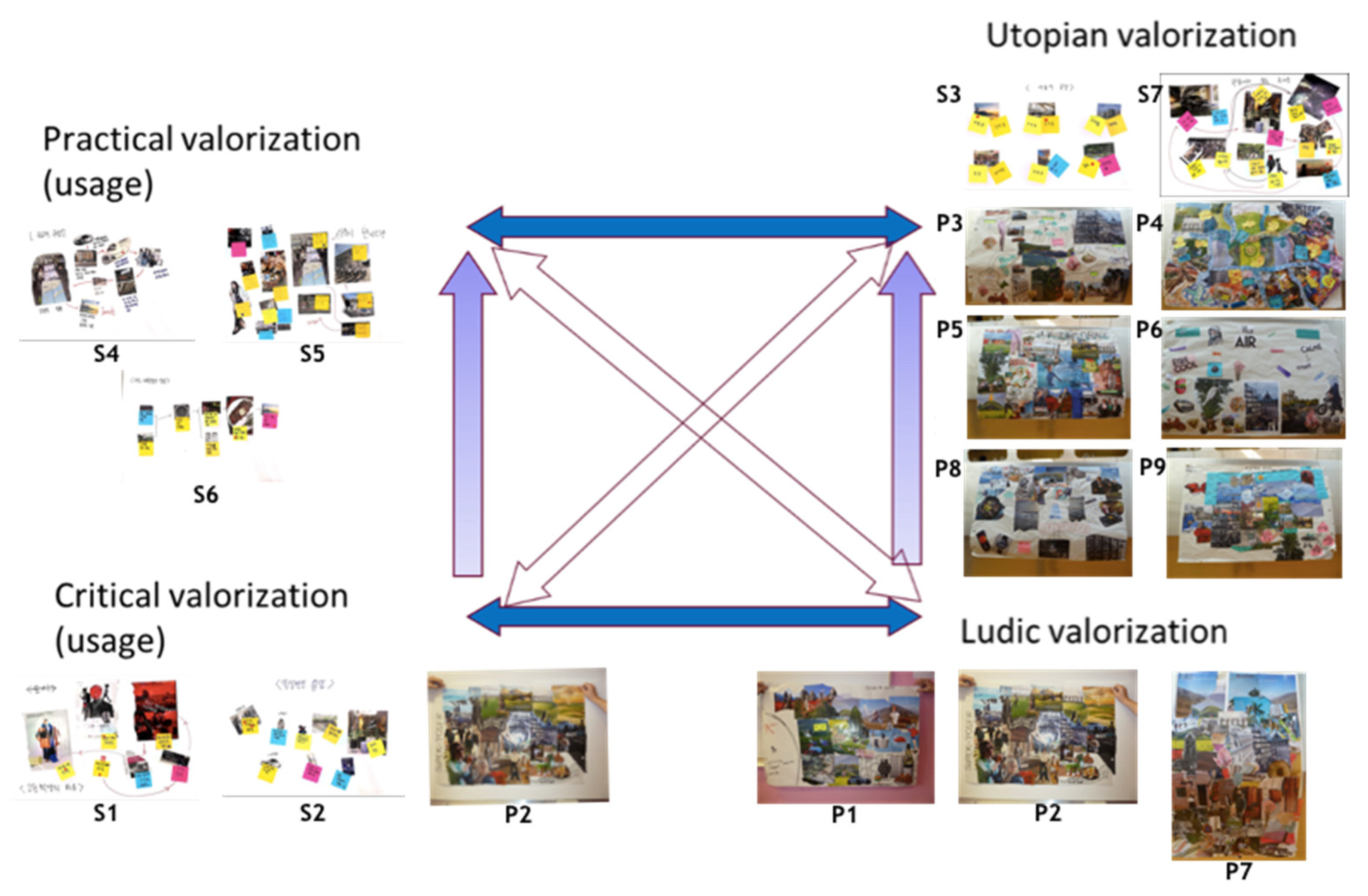

Semiotic Square

- Contradictions between contradictory signs on diagonal lines;

- Implications between complementary signs, orientated from the bottom to the top on vertical lines.

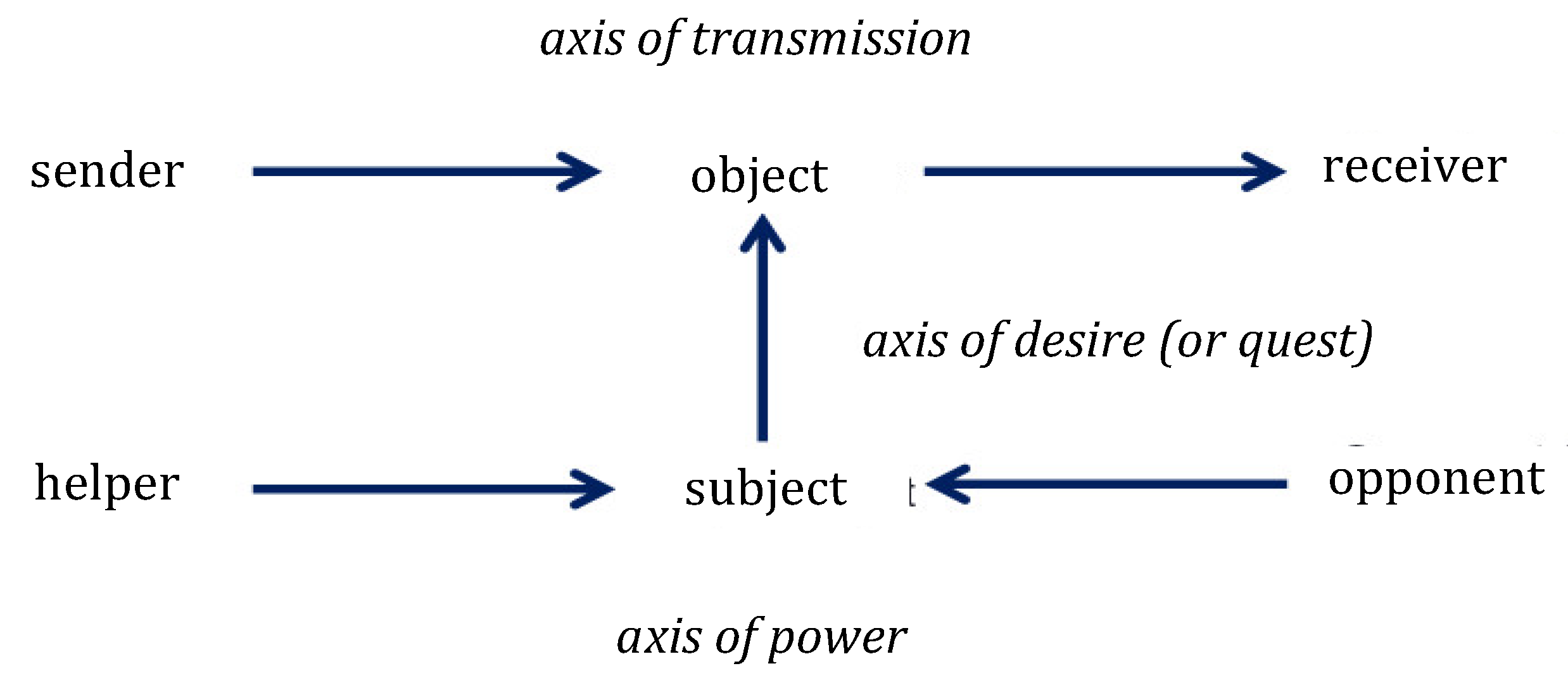

Actantial Model

- The quest (or desire) axis links the subject (or hero) to the object (of the quest);

- The transmission axis links, through the objects, the sender who initiated the quest to the receiver who benefits from it;

- The power axis opposes the helper to the opponent in their interaction with the subject.

2.2. Methodology

3. Results

Presentation: We have always thought that people in the city are always busy and busy. The first thing that comes to mind in Seoul is the crowded crowd at night. However, we think people feel a lot of tiredness because many people use subway public transport at similar times. We think people have a lot of interesting and fun activities to solve this fatigue. So, people are gathering together and enjoying it. To express this, we put a picture on the bottom left. And even in repetitive everyday life, many people spend a lot of time trying to find a lot of restaurants or a lot of cafes. Seoul has a high proportion think finding the joy in life when compared with other cities, go to the cafe through the act of enjoying food from places such as street vendors. And we thought that there are a lot of cars in Seoul and we can find many good cars in particular. But we thought the car noise was much worse than other cities. There are a lot of parks abroad, and in Seoul, there are more street trees than parks, so overall Seoul seems to have a strong forest feel. We thought that there was a small green space in the middle rather than a big park, so we put a picture in the middle. And the picture on the bot-tom right has recently had a lot of fine dust, so we tried putting people's attention.

Interview: We thought that the high population and vehicle density of the city could affect the noise of the city, and the environmental factors such as fine dust could also affect the soundscape visually and physically. These noises cause irritation and fatigue to people, and people think that they can get into the inner space such as restaurants and cafes to get out of it, to have fun or rest, or to find green spaces like forests. we felt that the overall feeling about the city was loud and desolate, and many people walked quickly in expressions. We thought that there were a lot of vehicles, a street tree, and a cafe.

B: so we have a city that is rather dynamic, so there are many people in the streets, there are singers, people who hitchhike, where we can eat too, with a whole new system: the food that is brought by small trains in the restaurants.

G: with cooks on board then who can, so who receive the orders, and who can prepare them on the train and suddenly they get the train around in town and it saves the number of cooks, so it's more handy. Uh then we also wanted to show that it was a city where there was a lot of animations, so there is a show of Harley motorcycles, as well as the singers, who are there to show that there is really a lot of entertain-ment in the city. Then we have a cycling club, right here, who likes to go for a little bit of a slam, and that's all there. We also wanted to show that this town could be in a lot of different sets, so we put icebergs, the mountain, and uh that. (Laughter)

B: And also we hesitated between putting either buildings or houses but we rather put buildings because it is more economical in terms of building materials, space, and that is what it is needed in the cities. Otherwise we put some cars that are all elec-tric of course, because we should not skimp on electricity, so I think that's it.

G: There are also cars that are also miniaturised. You can adopt your car. It's super handy. And we also have a lot of other means of travel like, so I had introduced the cycling club, but you can also come by bike to the restaurant, or on skateboard take his photos for insta, it can be handy. And I think I've been around, if you have any questions.

Mod.: What do the cars on the right mean?

G: It was to symbolize that there were, perhaps, still remnants of motorways, but that now there were no more gasoline cars on them ... that we did not destroy the mo-torways that's what I meant.

Mod.: So it's more to show the motorway than the cars actually?

G: Yes.

Mod.: And so why are all the characters in the lower left?

G: This is because it is the district of activity of the city and that the rest was rather for going on vacation, so uh... Finally, people are rather having fun in the city than going on vacation, but they can do it if they want to, that's why there's a little bit of it too, for example there are people who make a picnic, I don't know if we can see them.

Mod.: The hitchhikers who are in the centre, can you tell us about them?

G: In fact they wanted to go to the restaurant but they changed their mind, and they will go to the plain that is there. And so to go there, they are obliged to take the road that is there, but they do not have an electric car because they have no money.

Mod.: Okay, so it's characters who wanted to move to the right?

G: Yes, but also it is also as well to symbolize the cleaner means of transportation, like hitchhiking.

Mod.: Good; so they move to the right.

- First, find in the narration the hero and the object of the quest. Usually, these are rather obvious.

- Find the three tests of the quest, which are also rather obvious.

- Find the helpers and the opponents from the roles they play in the tests.

- Find the sender, usually the narrator, and the receiver, whom the narration is addressed to.

- Finally, fill in the other cells of the grid.

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with the Literature

4.2. Toward Guidelines for Soundscape Planning

4.2.1. Natural Elements as Helpers

4.2.2. Emotions and Feelings

4.2.3. Quest and Reward: Experiencing Soundscapes

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Polack, J.D.; Taupin, P.; Jo, H.I.; Jeon, J.Y. Guidelines for soundscape mapping and urban soundscape design derived from the imaginaries of digital native users. In Proceedings of the InterNoise2020, Seoul, Korea, 24–26 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Polack, J.D.; Taupin, P.; Jo, H.I.; Jeon, J.Y. Urban soundscapes in the imaginaries of digital native users in France and Korea. In Proceedings of the Forum Acusticum 2020, Lyon, France, 7–11 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Raimbault, M.; Dubois, D. Urban soundscapes: Experiences and knowledge. Cities 2005, 22, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aletta, F.; Kang, J.; Axelsson, Ö. Soundscape descriptors and a conceptual framework for developing predictive soundscape models. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 149, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taupin, P. The contribution of narrative semiotics of experiential imaginary to the ideation of new digital customer experiences. Semiotica 2019, 230, 447–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, A.F. Applied Imagination; Scribner: New York, NY, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Gatignon, H.; Gotteland, D.; Haon, C. Making Innovation Last; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, M.A.; Haley, E.; Bartel, S.K.; Taylor, R.E. Using Qualitative Research in Advertising. Strategies, Techniques, and Applications; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wunenburger, J.J. The Urban Imaginary: An Exploration of the Possible or of the Originary? In The City that Never Was; Exhibition Catalogue; Centre of Contemporary Culture of Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Torgue, H. Architecture et Territoire: Matières et Esprit du Lieu. Available online: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00503805/document (accessed on 24 May 2019).

- Greimas, A.J. Sémantique Structural, 2nd ed.; PUF: Paris, France, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Floch, J.M. La contribution d’une sémiotique structurale à la conception d’un hypermarché. Rech. Appl. Mark. 1989, 4, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Propp, V. Morphology of the Folktale; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, D. Categories as acts of meaning: The case of categories in olfaction and audition. Cogn. Sci. Q. 2000, 1, 35–68. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, E. Représentations individuelles, représentations collectives. Revue de Métaphysique et de Morale 1898, 6, 273–302. [Google Scholar]

- Greimas, A.J. Du Sens II—Essais Sémiotiques; Editions du Seuil: Paris, France, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, J.Y.; Hong, J.Y.; Lee, P.J. Soundwalk approach to indentify urban soundscape individually. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2013, 134, 803–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axelsson, Ö.; Nilsson, M.E.; Berglund, B. A principal components model of soundscape perception. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2010, 128, 2836–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, J.Y.; Hong, J.Y.; Lavandier, C.; Lafon, J.; Axelsson, Ö.; Hurtig, M. A cross-national comparison in assessment of urban park soundscapes in France, Korea, and Sweeden through laboratory experiments. Appl. Acoust. 2018, 133, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guastavino, C. The Ideal Urban Soundscape: Investigating the Sound Quality of French Cities. Acta Acust. United Acust. 2006, 92, 945–951. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/TS12913-1:2014Acoustics—Soundscape—Part 1: Definition and Conceptual Framework, ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1974.

- Giedion, S. Space, Time and Architecture: The Growth of a New Tradition, 5th ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer, K. What are emotions? And how can they be measured? Soc. Sci. Inf. 2005, 44, 695–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piano-Stairs. Available online: https://www.designoftheworld.com/piano-stairs/ (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Wood, W. Good Habits, Bad Habits: The Science of Making Positive Changes that Stick; Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Andreani, J.C.; Conchon, F. Les Techniques d’enquêtes Expérientielles: Vers une Nouvelle Génération de Méthodologies Qualitatives (Experiential Survey Techniques: Towards a New Generation of Qualitative Methodologies). Marketing Trend Congress. 2002. Available online: http://archives.marketing-trends-congress.com/2002/Materiali/Paper/Fr/ANDREANI%20CONCHON.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Pine, B.J., II; Gilmore, J.H. Welcome to the Experience Economy. Harvard Business Review. July–August Issue. 1998. Available online: http://www.academia.edu/download/33727940/pine___gilmore_welcome_to_experience_economy.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- DeJean, J. The Essence of Style: How the French Invented High Fashion, Fine Food, Chic Cafes, Style, Sophistication and Glamour; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Durand, G. Les Structures Anthropologiques de l’imaginaire, 11th ed.; Dunod: Paris, France, 1992. [Google Scholar]

| Matrix for Content Analysis of Experiential Narratives | Categories and Invariants | S7: Pleasure in “Repetition” |

|---|---|---|

| Actantial units Enunciations of “do” and “be” | Functions (“do”) | We think, use, gathering enjoying, spend time, find, go, enjoying food, walk quickly |

| Indices (“be”) + atmospheric indices | Busy and busy, comes to mind, feel, there are, car noise, street trees, putting people’s attention | |

| Categories of actants | Subject | Tired people |

| Object | Pleasure (cf. title) | |

| Sender | I or we (the authors of the collage) | |

| Receiver | People in the city | |

| Helper | Other people, food, greenery (cf. images) | |

| Opponent | Cars, dust (= pollution), crowd at night (top left and right + bottom right corners of the collage) = all that creates “noise” | |

| Initial lack | - | Tiredness, irritation, fatigue |

| Figures (sensory perception) and themes (concepts) Recurrence of semes that can be identified in several signs of the same text | Characters | We, people, crowd, vendors |

| Mythical figures | - | |

| Metaphors | Street trees = strong forest feel | |

| Rhetorical figures Hypotyposis | - | |

| Philosophical figures (Taoist way of thinking) | - | |

| Regrouping by themes and prototypical categories | Green, forest, | |

| Isotopies | We, people, fatigue, repetitive, everyday, high proportion, a lot of | |

| Isotopies that are “forms” of atmospheric components | Busy people, crowded at night, subway, a lot of restaurants, a lot of cars, car noise much worse than in other cities, street trees rather than parks, a lot of fine dust | |

| Euphoria vs. dysphoria (Positive-pleasure vs. negative-displeasure) | Feelings and emotions | Tiredness, interesting and fun, strong forest feel The city is loud and desolate, expressionless |

| 3 tests | Qualifying: Principal: Glorifying: | People together (bottom left image) Cafés (top middle image) Small green space in the middle |

| Value objects of the experiential quest | modal elements (competences) (know-how, can-do) | Can find many good cars, can get into |

| Value object of the quest | Finding the joy in life, have fun and rest, find green space | |

| Value object of transmission | Fun |

| Categories and Invariants | S4 “Composition of School Road” | S1 “High School Student’s Day” | P1 “Diver City” | P4 “Gif upon Bures” | S7 “Pleasure in “Repetition”” |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Actants in the Actantial Model | |||||

| Subject | We | I or we, high school student | People, we, I | We, one, people we know | Tired people |

| Object | Noise less audible | - | Living and very diverse landscape | Nature | Pleasure (cf. title) |

| Sender | We | We | We, it, I | We | I or we (the authors of the collage) |

| Receiver | - | - | People, they, we | Our friends, them | People in the city |

| Helper | The Han River, earphones, and music | Gathering with close friends, speech | Green spaces, the Calanques, hill, sea | Roads, railways, the ease of transportation | Other people, food, green (cf. images) |

| Opponent | Subway noise, tired road | Noise of the city, cold air | Concrete jungle, concrete, traffic | The airplane | Cars, dust (= pollution), crowd at night (top-left and right + bottom-right corners of the collage) = all that creates “noise” |

| Initial lack | - | Very tired every morning | Stimulating environment | Quick access to nature, no stop | Tiredness, irritation and fatigue |

| The 3 TESTS of the Actantial Model | |||||

| Qualifying test: Decisive test: Glorifying test: | - | - | Very urban part Very, very focused part on spirituality, religious Green spaces, quite varied landscapes | Park in the middle Activities around: bars, night outings Access to nature | People together (bottom-left image) Cafés (top-middle image) Small green space in the middle |

| Modalities (skills) modality of knowing- how-to-do, modality of being-able-to-do | Modeling, relaxed through earphones and music | - | We are null at drawing You can see, they can go, one cannot reach it, it can be said, it can replace, what one wants, one can project and see, it can represent | We can leave for where we want when we want, we can leave, one can go where one wants, looking around while moving, they can leave for where they want | Can find many good cars, can get into |

| Object of value (quest) | - | - | - | Leave the city, nature | Finding the joy in life, have fun and rest, find green space |

| Object of value (transmission) | Restoring fatigue, relax | - | We have a lot of things | Change air, what suits them … in their life | Fun |

| Valorisation | Practical | Critical | Ludic | Utopian | Utopian |

| Narrative | Helpers | Opponents | Feelings and Emotions | Reward | Val. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1: High school student’s day | Gathering with close friends, speech | Noise of the city, cold air | Anguished look, tired, I feel cold. The overall feeling for the city is despicable and indifferent. | - | C |

| S2: Everyday holiday | The five senses | A lot of daily noise, noise level | Unconsciously, not conscious, the feel of complex interaction with the five senses | The restaurant | C |

| S3: Daily life in Seoul | Sun, market, clothes, children talking | Crowded, noisy crowd | A sense of relief, desire to buy clothes, curiosity about what clothes to wear, a sense of achievement and hard feelings, some boredom and comfort at the same time, feel the concentricity | Relief | U |

| S4: Composition of school road | The Han River, earphones and music | Subway noise, tired road | Feeling tired | Restoring fatigue, relax | P |

| S5: Well-begun is half-done | Other places, restaurant, large mart, small party | School, graduation, Wangsin-ri street | Envious feelings, feeling of being lively and happy, feels warm to prepare for Christmas. Felt very loud, felt as loud and unpleasant noise, like loud and unpleasant nose, feel sympathetic, very sensitive, feels warm, not uncomfortable, feel good, do not feel at all sensitively. | - | P |

| S6: Everyday life of college students | Coffee, meat (?), acoustic environment | (Dangerous) scooter, professor’s voice, acoustic environment | The crowded, loud, and annoying feeling; were nervous, expressing noisy feelings, feel frustration and tiredness, feel relieved and satisfied, feel exhausted, our mind is finished. Feel nervous and uncomfortable, feel calm and warm, feels tense, feel frustrated; feel various discomfort, calmness, etc | Quality of life (?) | P |

| S7: Pleasure in “repetition” | Other people, food, green (cf. images) | Cars, dust, crowd at night, noise in the city | Tiredness, interesting and fun, strong forest feeling. Irritation and fatigue, the city is loud and desolate, expressionless | Finding the joy in life, have fun and rest, find green space | U |

| P1: Diver city | Green spaces, the Calanques, hill, sea | Concrete jungle, concrete, traffic | Dreary, sad, stimulating, alive, put in the spotlight, spiritual, mysterious, flourishing | Living and very diverse landscape | L |

| P2: Super pose | Train, electric cars, bike, skateboard, road, cleaner means of transportation | - | A little bit of slam, want | Car, plain Setting sun (on collage only) | C/L |

| P3: Universalis | Tourism that finances, chick districts | Abused men and women, cars | Quietly, nice, very pleasant to live, not too suffocating, more beautiful | Very pleasant city to live in | U |

| P4: Gif upon Bures | Roads, railways, the ease of transportation | The airplane | A cocoon, silent, “alone in front of oneself”, communicate the least, healthy loneliness | Leave the city, nature | U |

| P5: The floral city | Plate of food, forest, nature, on foot | Means of locomotion | - | The ideal city To live one’s life | U |

| P6: The air city | Nature, heritage, culture, electric cars, bikes, public transportation | Noise pollution | Quiet, sad, gray, warmer, nicer, pretty | Reinvent the city, make it close to nature | U |

| P7: Babylon | Nature, bikes, electric scooters, animals | - | - | Need for nature, for colors | L |

| P8: Serenissima | Bridges, paths, museums, cinemas, concert halls, restaurants, cafés, solar energy | Business district, regulated life, the new city | A little stressful, quiet and calm, nostalgia, soul, nice | The city Vintage style, history | U |

| P9: Title.exe | Belief(s), religions, superheroes, technologies, birds | The enemy | Quieter, more Zen, greener, more relaxing | Fresh start Live together in peace | U |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Polack, J.-D.; Taupin, P.; Jo, H.I.; Jeon, J.Y. Urban Soundscapes in the Imaginaries of Native Digital Users: Guidelines for Soundscape Design. Sustainability 2022, 14, 632. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020632

Polack J-D, Taupin P, Jo HI, Jeon JY. Urban Soundscapes in the Imaginaries of Native Digital Users: Guidelines for Soundscape Design. Sustainability. 2022; 14(2):632. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020632

Chicago/Turabian StylePolack, Jean-Dominique, Philippe Taupin, Hyun In Jo, and Jin Yong Jeon. 2022. "Urban Soundscapes in the Imaginaries of Native Digital Users: Guidelines for Soundscape Design" Sustainability 14, no. 2: 632. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020632

APA StylePolack, J.-D., Taupin, P., Jo, H. I., & Jeon, J. Y. (2022). Urban Soundscapes in the Imaginaries of Native Digital Users: Guidelines for Soundscape Design. Sustainability, 14(2), 632. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020632