1. Introduction

Green consumers may choose to purchase green products to minimize pollution and mitigate the global environmental crisis [

1]. While conventional consumers focus on maximizing immediate self-benefits, green consumers consider the long-term benefits of their purchases to others and the environment [

2]. For example, green consumers may choose recycled or remanufactured products to contribute to green development toward global sustainability [

3]. Meanwhile, businesses can engage in the green movement and create a green brand image by offering green products [

4]. There are many factors driving green purchase behaviors. According to the theory of planned behavior (TPB), behavior is directly influenced by behavioral intention. Specifically, the TPB identifies three antecedents of behavioral intention: (1) attitude, (2) subjective norms, and (3) perceived behavioral control. In the green product context, attitude has been the most important determinant of purchase intention. However, despite customers’ growing positive attitude toward green products, actual purchases of green products are still relatively low. Previous studies revealed the discrepancy between consumers’ favorable attitude toward green consumption and actual purchase behavior [

5]. For example, White et al. [

6] reported that 65% of participants in a recent survey stated that they would like to buy products that advocate sustainability, but only 26% of them did so. The gap between consumers’ desire and their actual actions can be referred to as the “green attitude-behavior gap”. The discrepancy between consumers’ green positive attitudes toward the environmentally-friendly products and the purchase of green products has been studied in previous literatures [

7,

8,

9]. Prior studies have attempted to close the “green attitude-behavior gap” by employing the TPB model [

10,

11]. Based on TPB, it has been proved that green purchase intention acts as the mediator of green attitudes and green purchase [

12,

13,

14], thus, it is crucial to establish green purchase intention among consumers to create opportunities for green products. Consequently, identifying relevant direct and indirect factors linking with TPB determinants and driving green purchase intentions is an important contribution to sustainable product marketing and sustainability.

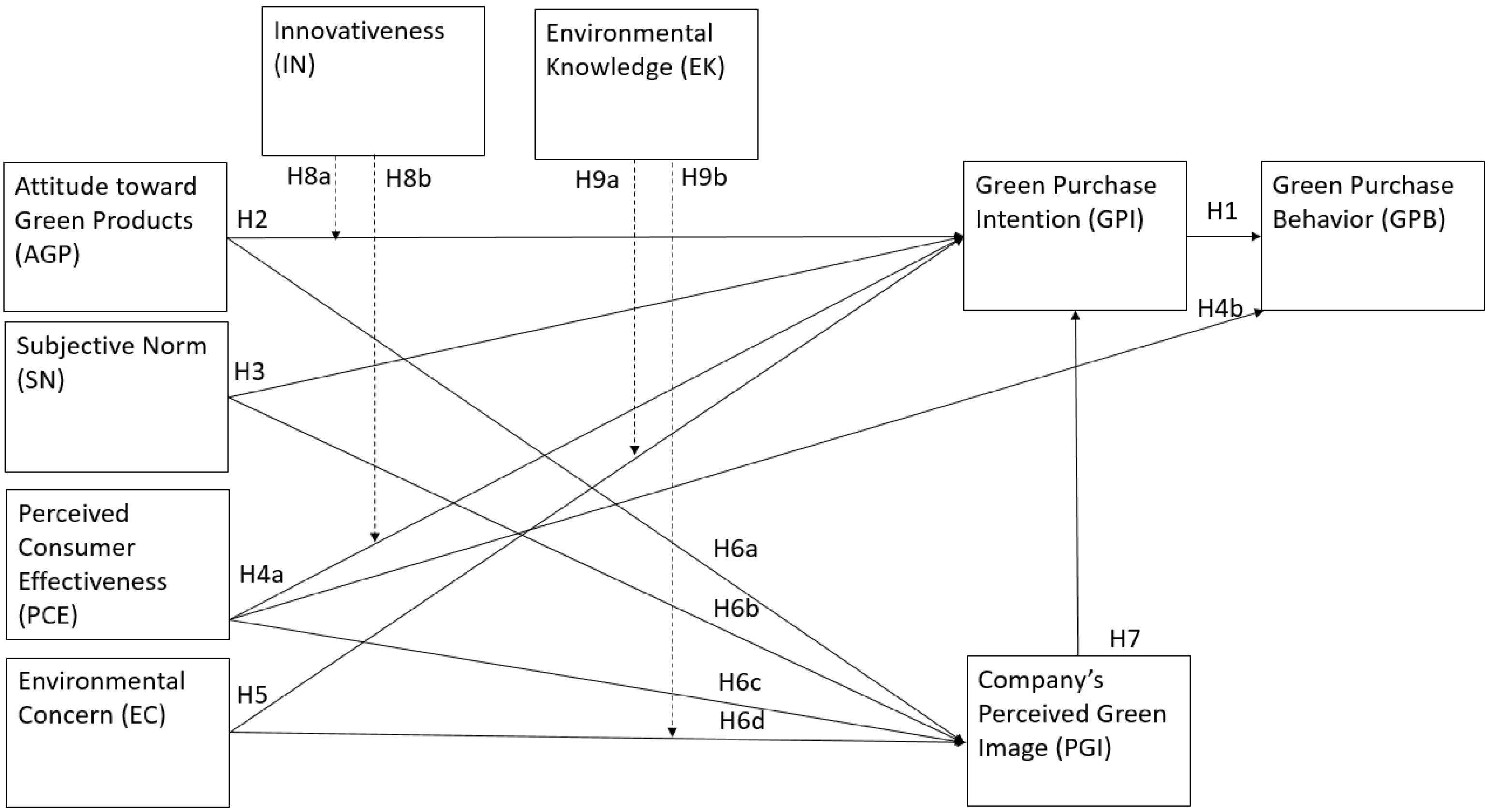

To complement the existing literature, this study proposed an extended TPB model with modifications in three aspects. First, we added environmental concerns as another antecedent of green purchase intention. In the green product context, apart from positive attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, consumers’ environmental concerns may directly impact green purchase intention. Second, we added the company’s perceived green image into the model to explore its plausible mediating role in encouraging green product purchase intention. Apart from the sales amount, which is the immediate goal of the business, marketers of green products should also focus on the company’s positive green image because the reputation of the producer significantly influences the product selection, and perceived green brand image significantly influences consumers’ green product selection [

15]. Green corporate image has been widely studied in hospitality research [

16,

17], and we aimed to extend the study on the influence of a company’s perceived green image on the consumer behavior in the context of green product purchase. Thus, marketers should increase the environmental value of products or services in the eyes of consumers to emphasize the distinction between green and non-green practices [

18]. Third, we suggested that consumer innovativeness and environmental knowledge may exert moderating effects on certain relationships. Markets for environmentally friendly goods are expanding with new green innovation. Consumers with a high level of innovativeness tend to have a stronger intention to buy green products [

19,

20]. This study attempted to examine the moderating role of consumer innovativeness on the relationship between attitudes and perceived behavioral control and green purchase intention. Furthermore, cognitive factors such as environmental knowledge are plausible factors affecting the intention and action of green product purchases. Aspara et al. [

21] identified that better knowledge leads to greater responsiveness and more engagement in environmentally friendly behaviors. Hence, we aimed to investigate the moderating effect of environmental knowledge on the relationship between environmental concerns and green purchase intention as well as the company’s perceived green image. The empirical evidence derived from this extended TPB model provides a guideline for green marketers on the factors enhancing the intention to purchase sustainable products.

In accordance with previous studies [

22,

23,

24,

25], structural equation modeling (SEM) was used for data analysis due to its applicability to demonstrate structural relationships in a complex model. Unlike other methods of statistical modeling, SEM supports the inclusion of both interdependent variables and interactions in a given phenomenon. SEM has been commonly applied in sustainability research such as supply chain management [

24], construction and architecture [

26], as well as green purchase intention [

27]. Therefore, it is appropriate for analyzing the proposed extended TPB model, which consists of antecedents, dependent variables, mediators, and moderators.

The remainder of this paper presents the empirical study and analysis. First,

Section 2 portrays the relevant literature review and hypotheses.

Section 3 explains the research methodology, while

Section 4 demonstrates the hypothesis testing results.

Section 5 discusses the theoretical and managerial implications. Lastly,

Section 6 concludes the main findings.

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Measurement Model

IBM SPSS 26 and Smart PLS 3.3 were applied to conduct the analyses and assess the quality of the measurement model. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was adopted to check the convergent validity and discriminant validity of the model. First, the internal reliability of the measurement model was investigated by using Cronbach’s alpha (α) and composite reliability (CR). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients exceeding 0.7 [

125] prove internal consistency. The CR for all constructs should be above 0.7 [

126]. As shown in

Table 2, Cronbach’s alpha and CR for all constructs were above the threshold values. Then, convergent validity was evaluated by examining whether the average variance extracted (AVE) values were above 0.5 [

127].

Table 2 illustrates that all AVE values are greater than 0.5, reaffirming that the items adequately reflect the constructs. Next, discriminant validity was tested using the Fornell–Larcker criterion [

127]. Discriminant validity is proved when a latent variable demonstrates more variance in its associated indicator variables than the variance of the other latent constructs in the same model. Accordingly, the square root of AVE for each construct should be larger than the correlations with other latent constructs [

128].

Table 3 shows that the square root of AVE for each construct is larger than the correlation between the constructs, thereby indicating the discriminant validity among constructs.

4.2. Structural Model

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was applied to test the hypothesized model. SEM is distinctive for its advantages of accounting for all covariance in the data, allowing the simultaneous analysis of correlations, shared variance, path coefficients, and their significance when testing for the main effects [

25,

129]. In accordance with previous studies [

23,

24,

27,

130,

131], instead of covariance-based structural equation modelling (CB-SEM), we performed partial least square equation modelling (PLS-SEM) because of its suitability in handling non-normal data. Moreover, PLS-SEM is more flexible in identifying the relationship between measurement items and the constructs, comparing with CB-SEM [

23,

132,

133,

134].

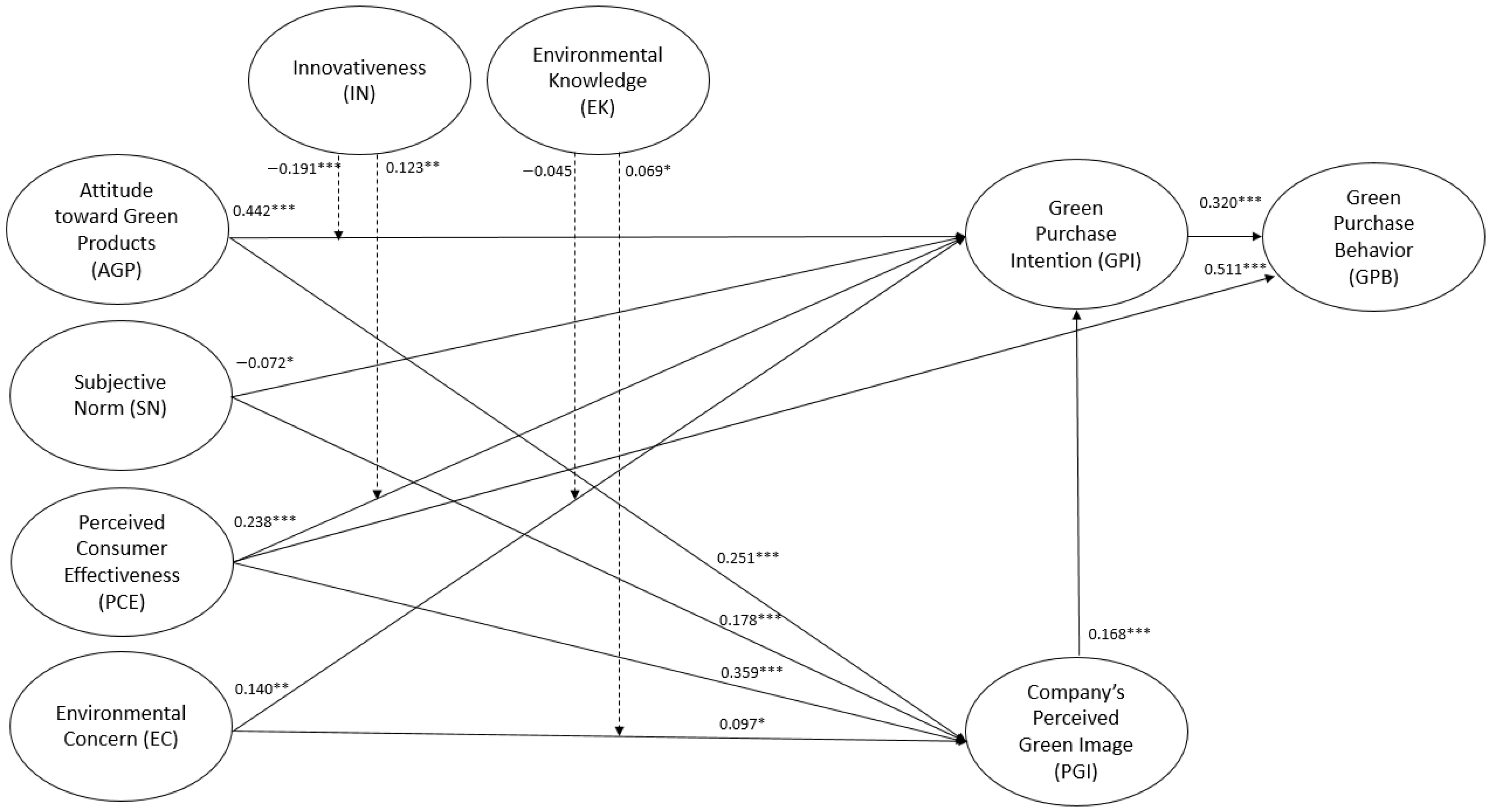

Figure 2 and

Table 4 show the results of the direct effects of the hypothesized model with the path coefficients in a standardized form. As displayed in

Table 4, green purchase intention (GPI) had a significant positive effect on green purchase behavior (GPB) (ß = 0.320, t = 7.704,

p < 0.001), providing support for H1 that intention to purchase can be an effective predictor of the actual purchase of green products. Attitude toward green products (AGP) had a significant positive effect on green purchase intention (GPI) (ß = 0.442, t = 9.560,

p < 0.001), validating H2. However, the relationship between subjective norm (SN) and green purchase intention (GPI) was statistically significant but not supported since the direction of the relationship was negative (ß = −0.072, t = 2.488,

p < 0.05). Hence, H3 was not supported.

Perceived consumer effectiveness significantly impacted both GPI (ß = 0.238, t = 4.846, p < 0.001) and GPB (ß = 0.511, t = 11.602, p < 0.001) in the positive direction. Thus, our findings supported H4a and H4b.

Environmental concern (EC) also showed a significant positive effect on green purchase intention (GPI) (ß = 0.140, t = 3.418, p < 0.01); therefore, H5 was supported.

Regarding H6, we proved that all four antecedents had a significant positive influence on the company’s perceived green image (PGI). Those four antecedents included attitude toward green products (ß = 0.251, t = 4.804, p < 0.001), subjective norms (ß = 0.178, t = 4.589, p < 0.001), perceived consumer effectiveness (ß = 0.359, t = 7.112, p < 0.001), and environmental concerns (ß = 0.097, t = 1.991, p < 0.05), providing support for H6a, H6b, H6c, and H6d. Last, we found that a company’s perceived green image had a significant positive influence on green purchase intention (ß = 0.168, t = 4.252, p < 0.001), implying that a positive green reputation eventually leads to purchase intention in the green product context.

4.3. The Results for Moderating Effects

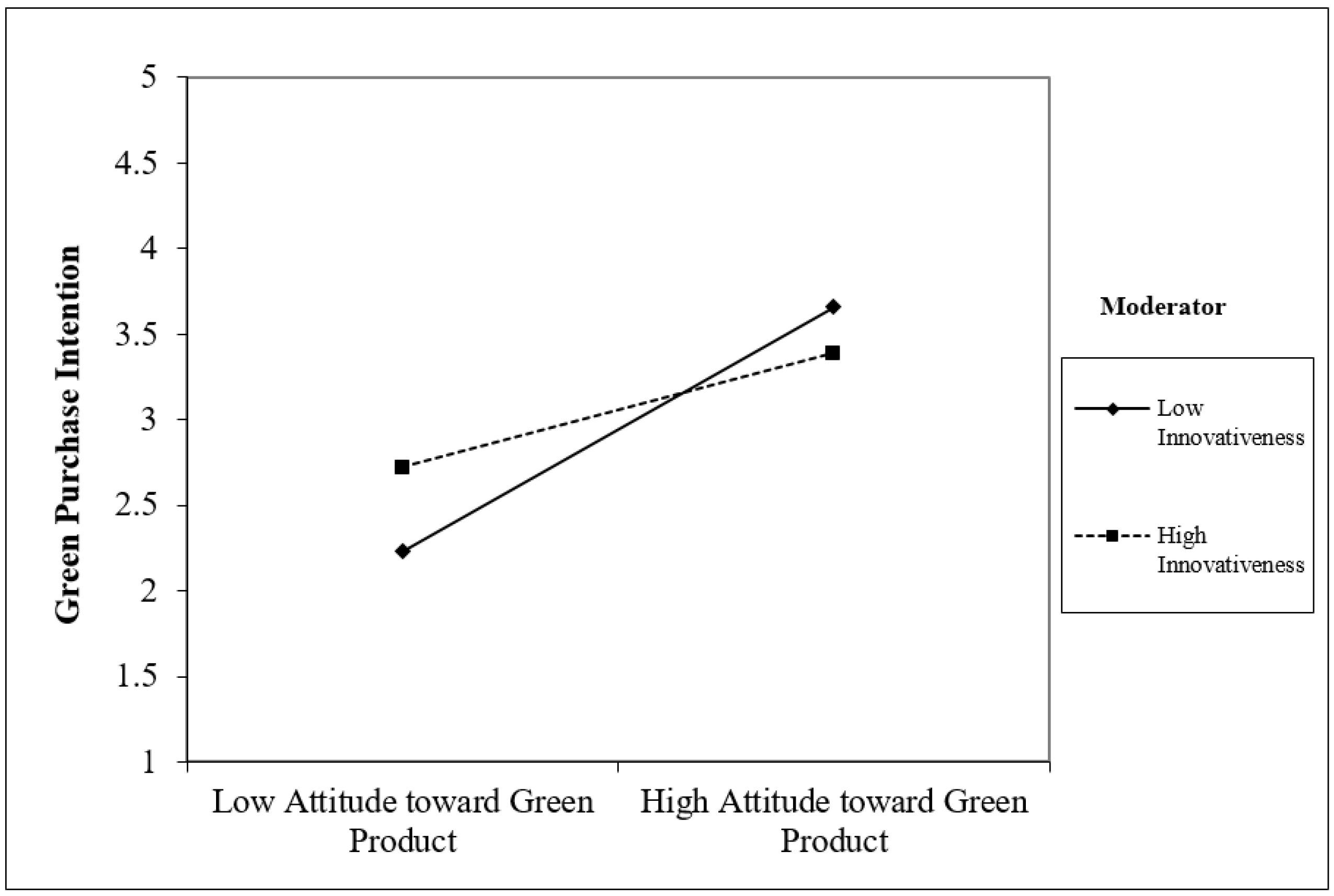

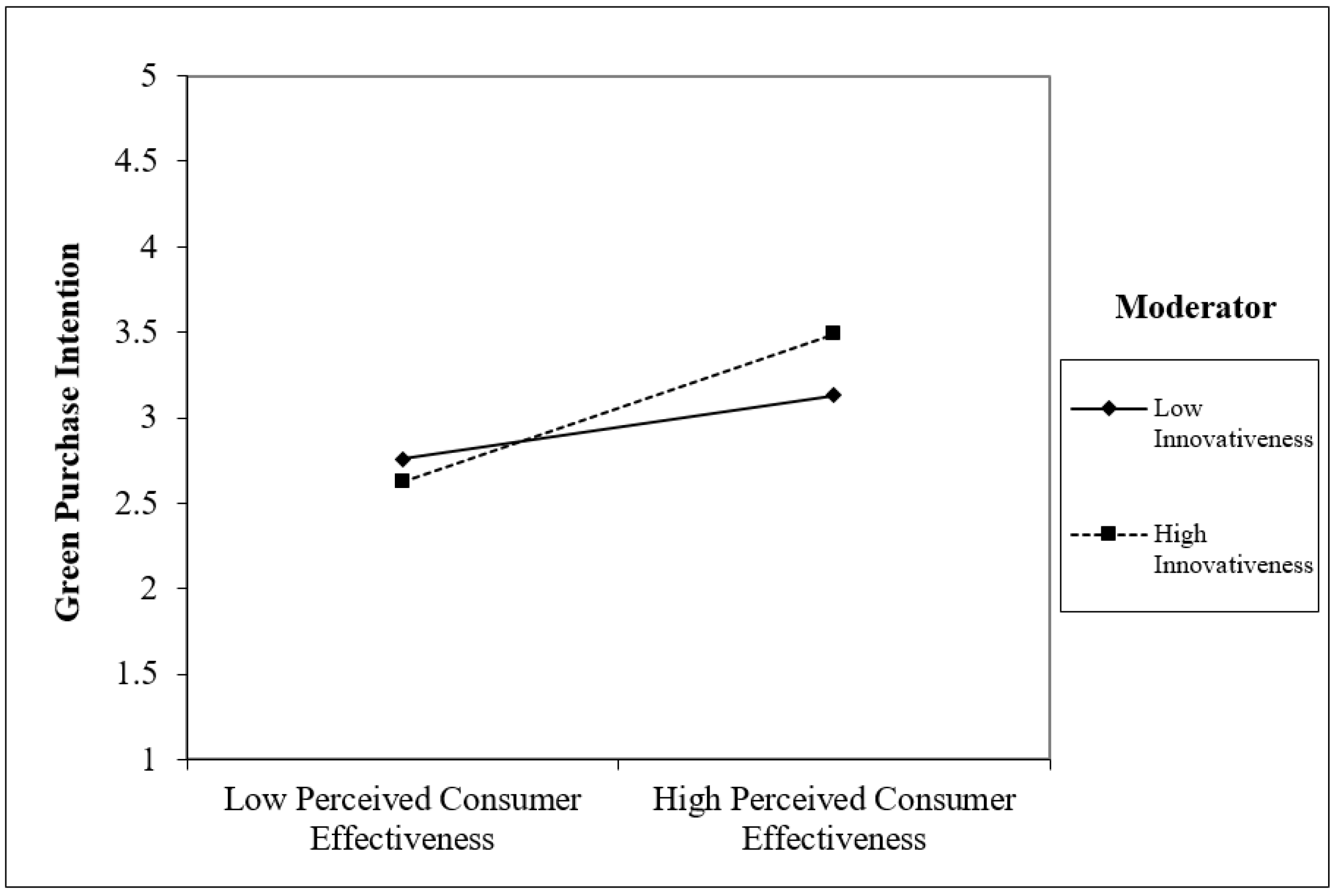

We used the latent moderated effect model to test the moderating effect of innovativeness (IN) and environmental knowledge (EK). To examine the moderating effect of innovativeness, we added the interaction term of attitude toward green products × innovativeness (AGP × IN) and perceived consumer effectiveness × innovativeness (AGP × IN) into the model. As illustrated in

Table 5, both interaction terms of IN showed statistically significant moderating effects. However, innovativeness negatively moderated the relationship between attitude toward green products and green purchase intention (ß = −0.191, t = 4.387,

p < 0.001), therefore H8a is not supported as we hypothesized that the moderating effect should be in the positive direction. Simultaneously, innovativeness positively moderated the relationship between perceived consumer effectiveness and green purchase intention (ß = 0.123, t = 2.800,

p < 0.01), thus, H8b is supported.

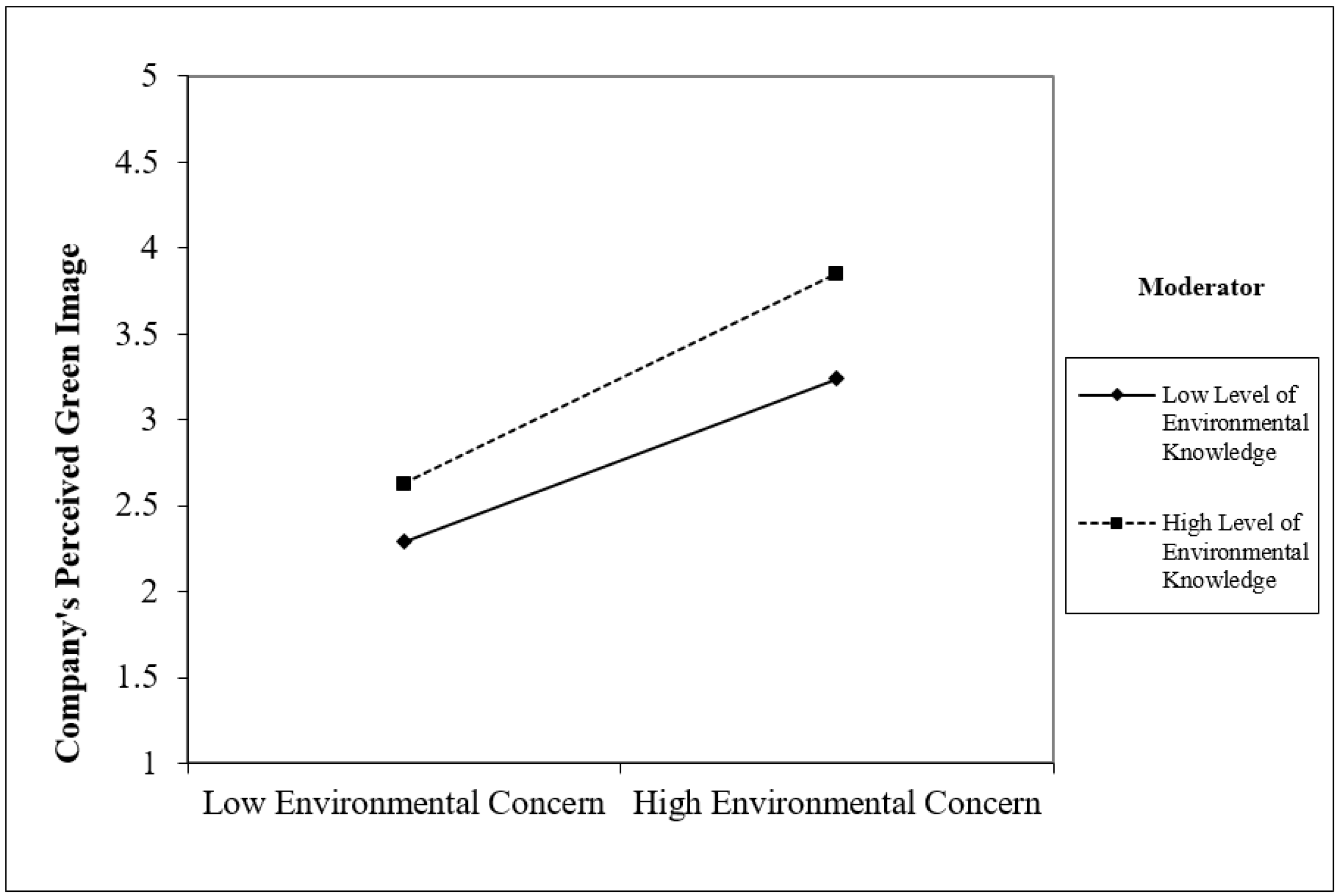

The moderating effect of environmental knowledge was investigated by adding the interaction terms of environmental concern × environmental knowledge (EC × EK) into the model.

Table 5 provides evidence that environmental knowledge did not significantly moderate the relationship between environmental concerns and green purchase intention (ß = −0.045, t = 1.818,

p > 0.05), therefore, H9a is not supported. However, environmental knowledge exerted a positive moderating effect on the relationship between environmental concerns and a company’s perceived green image (ß = 0.069, t = 2.013,

p < 0.05), hence, H9b is supported.

We followed the method of Dawson [

135] to visualize the moderating effect in a plot diagram.

Figure 3 shows that the positive relationship between attitude toward green products and green purchase intention weakened when consumer innovativeness increased.

Figure 4 shows that the relationship between perceived consumer effectiveness and green purchase intention strengthened when consumer innovativeness increased.

Figure 5 shows that the relationship between environmental concerns and a company’s perceived green image strengthened when the consumer’s level of environmental knowledge increased.

4.4. Multigroup Analysis

Acceptance and adoption of green products may vary across geographical locations due to factors such as cultural values [

31]. For instance, the recyclable materials are more relevant in the United States than in Germany, implying that consumers’ expectations on green products differ depending on where they live; thus, companies need to explore how targeted segments value the environment and green products [

136]. Previous studies have investigated the green purchase behaviors in developed countries such as the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan [

137,

138,

139]. Interestingly, in recent years, many have examined consumers’ selection of green products in developing economies [

45,

48,

51], signaling the potential of developing countries in promoting green consumerism and long-term resource efficiency. Apart from geographical locations, a consumer’s experience in using a green product also has a massive impact on whether they will continue to use it [

140]. Consumer perceptions of new green products are established based on indirect experience, which is insufficient to make a purchase decision. Furthermore, consumers with a high level of experience using certain products tend to have more direct experience-based information than consumers with a low level of experience [

141]. As a result, the amount of experience may have a distinct impact on the determinants of adopting green products.

Accordingly, we conducted two multigroup analyses to examine whether there is a difference between: (1) samples from developed and developing countries, and (2) samples with a high and low level of experience in purchasing and using green products.

Using the country as the grouping variable, we divided respondents into 711 (73.00%) from developed countries and 255 (26.18%) from developing countries.

Table 6 presents the results of the multigroup analysis (MGA) regarding the respondents’ country, pointing out one significant difference for the path of H1. The influence of green purchase intention on green purchase behavior is higher in developing countries than in developed countries (ß = −0.059,

p < 0.05).

Using the level of use experience as the grouping variable, we considered a green purchase experience value greater than or equal to 4.00 to be a high level of experience.

Table 7 explains the results of the multigroup analysis regarding the level of experience with green products, identifying the significant difference for the path of H6d. Environmental concern positively influences the company’s perceived green image when consumers already have a high level of experience with green products. In contrast, consumers with a relatively low level of experience with green products showed negative influences on the company’s green reputation (ß = 0.202,

p < 0.05).

5. Discussion

5.1. General Discussion

We employed the theory of planned behavior to examine the direct and indirect antecedents of consumers’ green product purchase behavior. As predicted in H1, green purchase intention appeared to be a meaningful predictor of green purchase behavior. Our model hypothesized four main antecedents of green purchase intention, and three of them, including attitude toward green products in H2, perceived consumer effectiveness (PCE) in H4a, and environmental concern in H5, significantly led to the intention to purchase the environmentally friendly product. Moreover, PCE also directly influenced green purchase behavior in a positive direction, confirming H4b. However, subjective norms were significantly related to green purchase intention but in the negative direction. Therefore, H3 was rejected, which contrasts with existing literature [

40,

49,

50]. The results implied that social norms do not necessarily play indispensable roles in the context of green purchases. Consumers might not pay attention to social influence when purchasing green product and individual self-driven and self-control (such as PCE) factors play more crucial roles in this context instead.

Our findings showed that all four antecedents, including attitude toward green products in H6a, subjective norms in H6b, perceived consumer effectiveness in H6c, and environmental concerns in H6d, significantly and positively influenced a company’s perceived green image. Furthermore, perceived green image significantly and positively affected green purchase intention, as hypothesized in H7. These significant relationships showed that the four main antecedents also relate to long-term marketing management by stimulating the company’s green reputation, and a positive reputation would eventually lead to actual future purchases through the mediating role of green purchase intention.

In addition, this study investigated the moderating role of consumer innovativeness, which is a consumer trait, and environmental knowledge, which is one of the cognitive factors. We found the negative interaction effect of attitude toward green products and innovativeness on green purchase intention. A negative interaction coefficient means that the two-variables effect is smaller than the sum of the single-variable effects. In this case, green purchase intention was established in both low- and high-innovativeness conditions. Consequently, the effect of attitude toward green products is more important than that of consumer innovativeness; therefore, H8a was not supported. Meanwhile, innovativeness positively moderates the relationship between perceived consumer effectiveness and green purchase intention; thus, H8b was supported. Accordingly, encouraging consumer innovativeness would be beneficial to targeting consumers with high PCE.

Finally, we explored the moderating effects of environmental knowledge. We found that environmental knowledge did not significantly moderate the relationship between environmental concerns and green purchase intention; therefore, H9a was not supported. However, environmental knowledge significantly and positively moderated the relationship between environmental concerns and the company’s perceived green image; hence, H9b was supported. The findings identified the potential of environmental knowledge to facilitate green product purchase via the company’s green reputation enhancement among environmentally conscious consumers.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

This study contributed to the existing literature by proposing the extended theory of planned behavior model to investigate consumers’ green product purchase behavior. First, while most previous TPB research identified that environmental concern acts as an antecedent of attitudes [

31,

79], our findings proved that environmental concern directly and positively relates to green purchase intention. Therefore, apart from attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, environmental concern is an impactful predictor of consumers’ intention to purchase green products. Second, we found that the company’s perceived green image mediates main antecedents and green purchase intention. Moreover, a company’s perceived green image directly relates to green purchase intention, implying that it indirectly stimulates green purchase intention via the mediating role of purchase intention. While most previous studies examined the impact of a company’s green image on customers’ attitudes and behavior in the context of service providers such as restaurants, hotels, and airlines [

16,

17], our study broadened research on companies’ green image in the context of green products. By boosting the company’s green image, a business can stimulate actual future purchases through the mediating effect of the green purchase intention. Notable, subjective norms do not directly impact green purchase intention, but they indirectly relate to future purchase intention via the mediating role of a company’s perceived green image, as green corporate image involves long-term reputation management.

Third, we added consumer innovativeness, which is a consumer trait, into the model to examine its moderating effect. While prior studies have investigated the antecedent role of consumer innovativeness on new product purchase intention [

19], our study proposed that consumer innovativeness plays a moderating role. We found a positive moderating effect of innovativeness on the relationship between perceived consumer effectiveness and green purchase intention. Therefore, for a consumer with high PCE, a higher level of innovativeness would positively enhance the purchase intention as one is more eager to try a new product. However, we found a negative moderating effect of innovativeness on the relationship between attitude toward green products and green purchase intention. It is possible that when a consumer already has a high sense of innovativeness, he or she tends to feel open and eager to try new products on the market. Hence, the relationship between attitude toward green products and green purchase intention weakens because the intention to buy the green product has already been influenced by innovativeness. Fourth, we added environmental knowledge, which is a cognitive factor, to the model to examine its moderating role. Previous studies have demonstrated that environmental knowledge is an antecedent of green purchase intention [

7,

77], while our study focuses more on the moderating effect. We found that environmental knowledge significantly and positively moderated the relationship between environmental concerns and the company’s perceived green image. However, environmental knowledge did not significantly moderate the relationship between environmental concerns and green purchase intention, but the relationship approached the significance level (

p = 0.069). The finding implies that a better understanding of environmental issues would indirectly enhance green purchases via the mediating role of green image. Thus, promoting environmental knowledge to consumers likely results in a positive green image of companies that offers green products and eventually results in consumers’ green product purchases.

Last, in line with the theory and hypothesized model, our empirical results showed that PCE influenced the purchase of green products directly and indirectly via the mediating role of green purchase intention. However, unlike previous studies [

7,

63], our findings revealed that the direct effect of PCE on green purchase behavior is more prominent than the effect of purchase intention. Therefore, apart from green purchase intention, encouraging a tremendous level of PCE would effectively lead to actual purchases.

5.3. Managerial Implications

Some managerial implications can be derived from the current study. First, marketers may encourage green product purchase intention by enhancing consumers’ environmental concerns. Apart from positive attitudes toward green products and perceived consumer effectiveness, our findings confirmed that environmental concerns also directly and positively influence green purchase intention. Therefore, promoting environmental concerns through advertising, marketing campaigns, and environmental education programs is recommended.

Second, marketers should also focus on not only consumers’ green purchase intention, but also their companies’ green image. Most of the time, businesses focus on generating income from sales without adequate focus on reputation management. A company’s green image is a powerful driver of its reputation. However, this relationship has only been widely studied in service sector contexts such as hotels and restaurants. This study has proven that a company’s green image also plays an influential role in sustaining a reputation for green products. It is recommended that marketers of environmentally friendly products pay attention to not only the sales amount but also the positive green image of the company. In the short run, marketers need to stimulate a positive attitude in consumers toward green products by enhancing the message framing by clearly explaining that green products are beneficial to customers, their families, and their communities. Encouraging more positive attitudes via messaging and advertising would lead to greater purchase intention and higher actual sales. However, social influence might not effectively stimulate green purchase intention, as we fail to confirm the antecedent role of subjective norms. Hence, it is preferable to focus on the positive impact of making a difference toward sustainability and to emphasize the ecological benefits. In the long run, marketers can stimulate future sales of sustainable products by strengthening the positive green image of a company. Drivers of a company’s green image include positive attitudes toward green products, subjective norms, perceived consumer effectiveness, and environmental concerns. By focusing on promoting green product features and benefits and companies’ positive green image, marketers can contribute to sustaining the green product business and encouraging sustainable consumption.

Third, encouraging consumer innovativeness can be a useful strategy to increase green purchase intention, especially for consumers who have a high level of perceived consumer effectiveness. To target customers who have strong beliefs that they can contribute to environmental protection by buying green products, we suggest stimulating sales by promoting new and innovative green products, as consumers with high innovativeness would want to try newly launched products that are less harmful to the environment.

Fourth, green marketers may emphasize consumers’ environmental knowledge to improve companies’ green image and increase sales. Environmental education is recommended to increase consumers’ awareness. As environmental knowledge positively moderates the relationship between environmental concerns and the company’s perceived green image, an environmental education campaign would eventually drive more purchases of green products via the company’s green image of offering ecologically friendly products.

Fifth, marketers of green products may choose to focus on a specific target market to increase green purchase behaviors in consumers. Consumers’ acceptance and selection of green products varies by country. In this study, we attempted to reveal differences between samples from developed and developing countries using multigroup analysis. The results showed that the effect of green purchase intention on green purchase behavior is higher in developing countries than in developed countries. If the firm focuses mainly on the immediate sales amount, then it may be more beneficial to target markets in developing countries.

Last, we employed multigroup analysis to test whether different levels of experience using green products modify the hypothesized relationships in the main model. The results revealed that consumers with a relatively low level of experience using green products showed a negative influence of environmental concern on the company’s green image. Meanwhile, consumers with a high level of experience showed a positive influence of environmental concern on the company’s perceived green image. Therefore, marketers should provide more opportunities for consumers to try and become familiar with green products to enhance the company’s positive green image and eventually result in future purchases.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Despite the adequate number of statistical samples, the generalizability of our findings may be limited. Among all 974 samples, 50% are from the United States, while 31% are from Asia. We lacked samples that represent Europe, Australia, and Africa; thus, the interpretation of the findings may not be applicable to these populations. Future research may adopt sampling methods that result in more globally representative samples. Alternatively, future research may be conducted in certain countries of interest to green products.

In addition, the measurement items used in this study were modified from the existing literature; therefore, they may fail to cover newly established aspects of the green consumer market. Future research might include add-ons to the field of green marketing by developing new measurement tools that reflect modern consumer perception and behaviors. Moreover, measurements other than questionnaire surveys may be applied to complement the empirical investigations. For instance, the measurement of environmental knowledge may be in the form of quizzes on environmental awareness.

Ultimately, using a one-time questionnaire survey may not perfectly eliminate concerns of common method bias. Furthermore, the results collected cannot reflect a causal relationship between the variables. Concerns of common method bias may be addressed by: (1) requesting the respondents to complete each part of the questionnaires at different time points and (2) using different data sources for each variable. For example, green purchase intention can be measured by a self-report questionnaire, while green purchase behavior can be captured by actual purchases of the respondents during a specified period. Meanwhile, quasi-experimental or experimental research should be conducted to empirically demonstrate a causal effect and enable manipulations of the relationship between relevant constructs.

6. Conclusions

The current study investigated the factors driving consumers’ purchase of green products based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). We extended the TPB model by including environmental concern as a new antecedent, a company’s perceived green image as a mediator, and consumer innovativeness and environmental knowledge as the moderators. The findings showed that in addition to green attitudes and perceived consumer effectiveness (PCE), environmental concern also influences consumers’ intention to purchase green products. Furthermore, our empirical results confirm that a company’s perceived green image mediates the relationship between other antecedents and green purchase intention. Therefore, to close the green attitude-behavior gap, green marketers should try to encourage purchase intention by promoting positive attitude toward green product, perceived consumer effectiveness, and environmental concern to drive immediate sales. At the same time, future sales can be encouraged by establishing a positive green image of the company. Particularly, marketers may focus on target consumers with high PCE by launching new types of green product, because consumer innovativeness positively moderates the relationship between PCE and purchase intention. For both marketers and policymakers, environmental knowledge should be promoted via educational institutions, broadcasts, press, social media, and other types of media, as it positively moderates the relationship between environmental concern and a company’s perceived green image.