1. Introduction

The new 2023–2027 CAP [

1] will be based on a new policy delivery model that will shift ‘from compliance to performance’. According to this model, the member states (MS) will have increased subsidiarity for planning and implementing CAP. Each MS will establish a single CAP ‘strategic plan’ (SP) covering interventions for both Pillar I (direct payments) and Pillar II (rural development). The preparation of the plan shall be based on quantitative and qualitative up-to-date information that provides a thorough analysis of the current situation in the country, it shall actively involve all related economic and social partners and it shall be connected to a set of common economic and biophysical indicators defined in the regulation.

One key issue for CAP strategic planning in the Greek case is related to the treatment of historical entitlements. These are entitlements to CAP payments with a unit value (i.e., value per hectare) related to the payments that a farmer received in the past. It first appeared in the 2003 Fischler CAP reform and is still applied in several MSs, albeit indirectly, as we explain in a subsequent section.

Historical entitlements lead to an unequal level of payments per hectare that reflects the pre-decoupling CAP regime. Two neighboring plots that belong to different farms may receive different payments per hectare, e.g., if the farms were used for different purposes, growing cotton and trees, for instance. In such cases, it is difficult to justify their maintenance under the CAP’s rationale of decoupled payments.

Indeed, the academic literature has explored their abolishment, especially in the periods preceding the discussions on CAP reforms. Matthews et al. [

2] used a GIS model to explore the effects on Scottish agriculture of abolishing historical entitlements and replacing them with a single area payment. Rochi [

3] used a social accounting matrix to examine the distributional effects of replacing historical entitlements in Italian agriculture with a regional flat rate. Ciaian et al. [

4] discussed the impact of different entitlement settings on the capitalization of the CAP payments. Marchand et al. [

5] simulated the impact of a flat rate system for Flanders using a positive mathematical programming model. Severini and Valle [

6] used a theoretical model to explore the relation between the availability of entitlements and land shadow prices. Erjavec et al. [

7] and Gocht et al. [

8] went even further by exploring the impact of an EU-wide flat area payment for CAP, i.e., the payment per hectare to be equal for any hectare in the EU.

From the political and policy side, there was also pressure for leaving historical entitlements behind. The process of decoupling the payments from any actual production choice was incompatible with the entitlements as the latter represented the coupled payments regime. In addition, CAP’s justification was moving slowly from food security and productivity towards the reward of public goods and the offering of ecosystem services. These were also incompatible with the entitlements. Their introduction was a compromise between the new CAP philosophy and the political need to introduce radical reforms gradually. Thus, very soon after their introduction in 2003, the 2008 CAP ‘Health Check’ [

9] called for a ‘move away from paying farmers on the basis of historical production towards a more even distribution per region’. The 2013 CAP reform [

10] introduced the ‘convergence’ process that would reduce variation between payments per hectare. In the current reform, the EU Parliament Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development in 2018 [

11] calls for modernizing the value of entitlements based on “historic references”. Finally, the new CAP regulation [

1] sets a minimum convergence threshold of 85%. This means that by 2027 no farm should have a payment per hectare of less than the 85% of the average value. This threshold is much closer to a uniform payment per hectare than the 60% threshold of the previous CAP.

Therefore, for Greek CAP strategic planning, the abolishment of historical entitlements seems to be a reasonable option. Still, this comes with some implications regarding the income of small farms. We gain some qualitative insights when we examine the distributions of payments per hectare and payments per farm.

The distribution of payments per hectare and per beneficiary for the different EU countries is shown in

Table 1. Greece had the highest variability (expressed with the interquartile range) in the EU, with many farms that received payments of more than 1000 euros/hectare and many other farms that received less than 100 euros/hectare. At the same time, Greece is among the member states with the lowest dispersion in the level of payments per farm.

Thus, although some farms receive very low payments per hectare and some others receive very high payments per hectare, their payments at the farm level are equal. This happens because the entitlements with high unit values belong to small farms, while the large farms possess low-value entitlements.

The abolishment of historical entitlements will lead to leveling the payment per hectare for all farms. This will reduce the total payments to small farms, since they have less land, and will result in transferring resources to larger farms. Moreover, if the distribution of high- and low-value entitlements is correlated with agricultural sub-sectors, it will be possible to have budgetary transfer across these sub-sectors. In order to take a well-informed decision, the above effects need to be quantified.

The objective of this paper is to provide insights related to the abolishment of historical entitlements. What will be the effect of the abolishment of the historical model on incomes across the various types of farming and farm economic sizes? How can policy makers use the intervention of redistributive payment to reverse any negative income effects? In order to answer these questions, we use static simulations that project income effects on the different economic sizes and types of farming. The innovative aspect of this research is twofold: first, there is the modeling of the redistribution scheme; and, second, there is the exploration of the effects of the abolishment of historical entitlements that is relevant for the strategic plans of ten MSs, as shown in the following section.

We first present a timeline of the historical entitlements across the various CAP reforms. Then, we present the simulated scenarios, the simulation steps and the data used. Finally, we present the results and close the paper with a discussion of our findings and our conclusions.

2. The Historical, Regional and Convergence Models of CAP

As we briefly show in

Table 2, CAP has evolved along two main axes. The first relates to the objectives of CAP, which initially focused on increasing productivity and gradually moved to environmental concerns. The second axis relates to the mechanisms employed, shifting from market to producer support and then to decoupled support.

The introduction of the historical entitlements came with the 2003 Fischler reform. The entitlements served the purpose of a smooth transition from the ‘producer support’ of the 1992 CAP (activity-specific payments related to the level of activity) to the decoupled payment regime of the 2003 CAP (payments decoupled from specific activities, not related to the level of activity). For this, the member states had the discretion to choose between two different implementations of the decoupled Single Farm Payment: a historical model that was based on historical entitlements and a regional model that was completely breaking the ties with the ‘producer support’ of the 1992 CAP [

15].

Under the historical model, transfers to farmers via the Single Payment Scheme (SPS) equaled the financial support they received in the ‘reference period’ (2000–2002), thus maintaining intact the past distribution of coupled payments across farmers. More specifically, according to this model, every farm received a Single Payment equal to the average payment for arable crops, beef and veal, milk, sheep and goat meat, olive trees, raisins, etc., that it had received in the 2000–2002 reference period. For example, a farm that specialized in cotton for 2000, 2001 and 2002 would receive a higher per hectare payment in CAP 2005–2013 compared to a farm growing apples, since cotton had high payments per hectare while apples had almost zero.

By contrast, under the regional model, all farms in a specific region received the same flat rate payment per hectare; the MSs could freely define the regions based on objective criteria or set a single flat rate payment for all farms at the country level. There was also a so-called hybrid model, where MSs could provide part of the single payment based on historical payments with the rest based on the flat rate per hectare payment. According to whether a part of historical payments was fixed or varied over time, there was a further distinction between static hybrid and dynamic hybrid models.

With the advent of the 2013 CAP, the Single Payment was split into different components. The most important were the Basic Payment and a ‘Greening Payment’ (its full name was ‘Payment for agricultural practices beneficial for the climate and the environment’). The MSs that applied the historical model had to move towards a flatter payment per hectare for the Basic Payment. This adjustment was termed internal convergence and the rate of the adjustment was left within a certain range at the MSs’ discretion. The available convergence options were: (a) a uniform unit value of payments effective either in 2015 or in 2020 (full convergence) or (b) a partial convergence of unit value of payments, so that by 2020 no farm has a very low value of payment per hectare. The redistributive scheme was also introduced, which allowed MSs to provide an extra payment per hectare to smaller farms. For the new MS, a simplified flat rate payment called SAPS (Single Area Payment Scheme) was also available.

In the 2023–2027 CAP, the Basic Payment Scheme will be renamed to Basic Income Support for Sustainability. The Redistributive Payment will become the Complementary income support and will be mandatory for member states to apply. Convergence for Basic Income Support is still an option, albeit more strict, so that no farm at the end of 2027 will have an entitlement value less than 85% of the average entitlement value.

We provide a summary of the above timeline in

Table 3.

In the 2003 Fischler reform, Greece selected the historical model, assigning entitlements to farms and connecting the value of each entitlement to the average payment that the farm received in 2000–2002 (implemented in 2008). Then, in the 2013 reform, it followed the partial convergence model. Three agronomic regions were defined: arable land, grassland/pasture and permanent crops. The flat-rate target value was different for each of those regions: 420 euro/ha for arable land, 500 euro/ha for permanent crops and 250 euro/ha for grassland. The implementation details of the Greek regional model were such that a farm could possibly hold some entitlement rights from the arable land region, others from the grassland region and others from the permanent crop regions. Thus, the actual payment that a farm received was an average of the regional payments weighted by the number of entitlements it held in each region. At 2019, due to the convergence, no unit value should be lower than 60% of the regional target flat-rate and the unit values that exceeded 100% of the regional average should have been reduced.

3. Scenarios, Data and the Simulation

The scenarios we simulate have two dimensions. The first one related to the abolishment or preservation of the historical entitlements and the second to the redistribution scheme.

Along the first dimension, we examine three configurations. The first scenario, named C85, is an accelerated convergence model, where, by the end of the programming period, no payment will be lower than 85% of the regional average. This corresponds to maintaining the historical entitlements. The second scenario, named R_F, is a regional flat-rate payment, i.e., within each region all farms receive the same payment per hectare. The third scenario, named C_F, is a country-level flat-rate payment, i.e., all farms in the country receive the same payment per hectare. The last two scenarios correspond to the abolishment of historical entitlements.

We combine these three scenarios with the redistribution measure, which is a mandatory intervention in the forthcoming CAP. For this, we keep the redistribution budget constant at 10% of the direct payments budget and we vary the redistribution payments per hectare. Since the budget remains constant, higher payments per hectare will result in fewer farms getting higher payments per hectare for redistribution and lower payments per hectare will have the opposite effect. We consider two relatively extreme cases. One is relatively tight in terms of how many farms benefit from redistribution and is therefore named R_few. In this scenario, we set the redistributive payment per hectare to be 55% of the maximum allowed payment per hectare, resulting in only around 30% of the farms getting redistribution payments. A second redistribution scenario, named R_many, provides a lower redistribution payment per hectare (25% of the maximum allowed payment), so that around 50% of the farms benefit from redistribution.

A summary of the scenarios is presented in

Table 4.

The simulation data is an anonymized random sample of 20,000 farms from the Greek payment authority (OPEKEPE) and corresponds to payments for 2019. For those farms, we have the total value of payments and the number of their entitlements for each agronomic region. In 2019, convergence had already terminated, so this data is valid until the new CAP becomes applicable on 1 January 2023. We also have for each farm the areas for each type of agricultural activity (e.g., durum wheat, barley, apple trees, etc.). Based on this information, we simulated the Type-of-Farming methodology used in the EU’s Farm Accountancy Data Network (FADN), and we assigned each farm to an FADN economic size and Type-of-Farming group.

The simulation steps are as follows. First, we assume that the basic payment (BPS) budget (including greening) of the current CAP 2014–2020 is represented by the payments of the sample farms (Equation (1)). We then deduce the represented national direct payments of CAP 2014–2020 from the BPS of CAP 2014–2020 using a multiplication factor (Equation (2)). In the 2014–2020 CAP’s national envelope for Greece, the basic payment was 871,068,024 euros per year, the direct payment budget was 1,818,660,043 euros per year and the multiplication factor was equal to their ratio, i.e., to 2.171656. Finally, we assume that the redistribution budget of the new 2023–2027 CAP will be 10% of the direct payments. The latter remains constant for both the current and the new CAP (Equation (3)). The new basic payment for 2023–2027 will be that of 2014–2020 with redistribution subtracted (Equation (4)).

where

is the CAP 2014–2020 national basic payment budget of our sample (greening is included),

is the payment for farm

f in agronomic region

r (as found in the data),

is the estimated sample’s direct payment (Pillar I) budget,

is the estimated sample’s redistribution budget and

is the CAP 2023–2027 national budget for the basic income support for the sustainability of our sample.

Then, for each farm and scenario, we estimate the new basic payment. For the two flat-rate scenarios, this is relatively straightforward. In the countrywide flat-rate scenario, each farm will receive the payment per hectare (it is the same across all farms) multiplied by the number of rights it holds (Equation (5)). In this scenario, the payment per hectare equals the 2023–2027 budget divided by the number of rights of all farms (Equation (6)).

For the regional flat-rate scenario, the payment for each farm is the sum of the payments for each agronomic region that it has rights to (Equation (7)). In this case, the payment per hectare is different for each agronomic region and depends on the share of the budget that was allocated in the 2014–2020 CAP to each region (Equation (8)).

where

is the CAP 2023–2027 basic payment of farm

f for the countrywide flat-rate scenario (euros),

is the payment per hectare for the countrywide flat-rate scenario (euros/ha),

is the number of rights of farm

f in agronomic region

r (ha),

is the CAP 2023–2027 basic payment for farm

f in the regional flat-rate scenario (euros),

is the estimated sample’s direct payment (Pillar I) budget,

is the payment per hectare for region

r in the regional flat-rate scenario (euros/ha) and

is the share of the CAP 2014–2020 budget that was allocated to region

r.

In the case of the convergence scenario, the estimations are a bit more complex. The new basic payment is the product of the rights the farm has in each agronomic region multiplied by a farm-specific payment per hectare (Equation (9)). This farm-specific payment depends on the relative position that the farm has in the regional payment-per-hectare distribution (Equation (10)). If the farm’s payment per hectare is between 85% and 100% of the regional average, then its payment per hectare does not change. If it is below 85%, then its new payment per hectare is set to 85% of the regional average, as at the end of the convergence period (2027) no farm shall be below this position. If the farm is above the average, the payment per hectare is reduced by a farm-specific ratio, so that the new CAP 2023–2027 basic payment budget equals the 2014–2020 budget. The calculation of this ratio is too complex to be presented here but the reader can find it in the simulation code in the

Supplementary Material.

where

is the CAP 2023–2027 basic payment of farm-f for the convergence scenario (euros),

is the CAP 2023–2027 payment per hectare for the convergence scenario, for farm

f and region

r (euros/ha),

is the CAP 2014–2020 payment per hectare from the data for farm

f and region

r (euros/ha),

is a farm-specific reduction of the CAP 2014–2020 payment per hectare (%) and

are the classes of farms according to the relation of their payment per hectare under CAP 2014–2020 to the regional average.

The above calculations are related to the basic payment of the new CAP 2023–2027. We also need to calculate the redistributive payment. As described at the beginning of the section, we have defined the two redistributive scenarios in relation to the maximum value that the redistribution unit value can theoretically take, i.e., according to the regulation, this equals the direct payment budget distributed to all entitlement rights (Equation (11)). We then estimate the redistribution payment of each farm. In Equation (12) we give the mathematical notation of its calculation. Its details are rather complex to explain here but they are well explained in the simulation script in the

Supplementary Material. Each scenario starts with the definition of a percentage of the maximum theoretical payment per hectare of redistribution (

). This leads to an estimate of an area threshold for each region that determines which farms will benefit from redistribution so that we do not exceed the redistribution budget (

). This also requires defining the number of hectares for which redistribution will be paid (

). If a small farm has 10 ha but redistribution will be paid only for the first 5 ha, then the payment for this farm will be only for its first 5 ha.

where

is the theoretical maximum payment per hectare of redistribution,

is the set of farms that are eligible for getting redistribution in scenario

s,

is the percentage of the maximum theoretical payment per hectare of redistribution for scenario

s (%) and

is the number of hectares for which redistribution will be paid (ha).

After estimating the basic payment for the three historical entitlement abolishment scenarios and the redistribution payments for the two redistribution payment scenarios, we estimate for each farm the overall payment difference between CAP 2014–2020 and CAP 2023–2027.

We provide the simulation script in the

Supplementary Material. It contains detailed comments so that one can follow the algorithm. It is coded in R and we provide instructions on how to run it and how to obtain the results that we present in the paper. Unfortunately, due to confidentiality issues, we cannot share the original dataset but instead we share a permutated version of it. The original records have been partitioned into several groups, and the values of each of the columns are shuffled within each group (for more information, see Majeed et al. [

17]). Thus, the reader will get slightly different results when running the script with the permutated data, but it is a compromise between the needs for research reproducibility and data confidentiality.

4. Results

First, we explore the direct effects of abolishing the historical entitlements. We compute them by comparing each of the two flat-rate scenarios (C_F and C_R) with the convergence scenario (C85).

In general, as expected, the abolishment leads to a payment decrease for farms of small economic size and a corresponding increase for those of high economic size (

Table 5). For farms with an economic size of less than 8000 euros, a reduction of approximately 10% takes place in the C_F (flat rate at the country level) scenario and one of 5% in the R_F scenario (flat rate at the regional level). This means that payments are transferred from small to large farms. However, the regional flat rate (scenario R_F) leads to a lower transfer of payments.

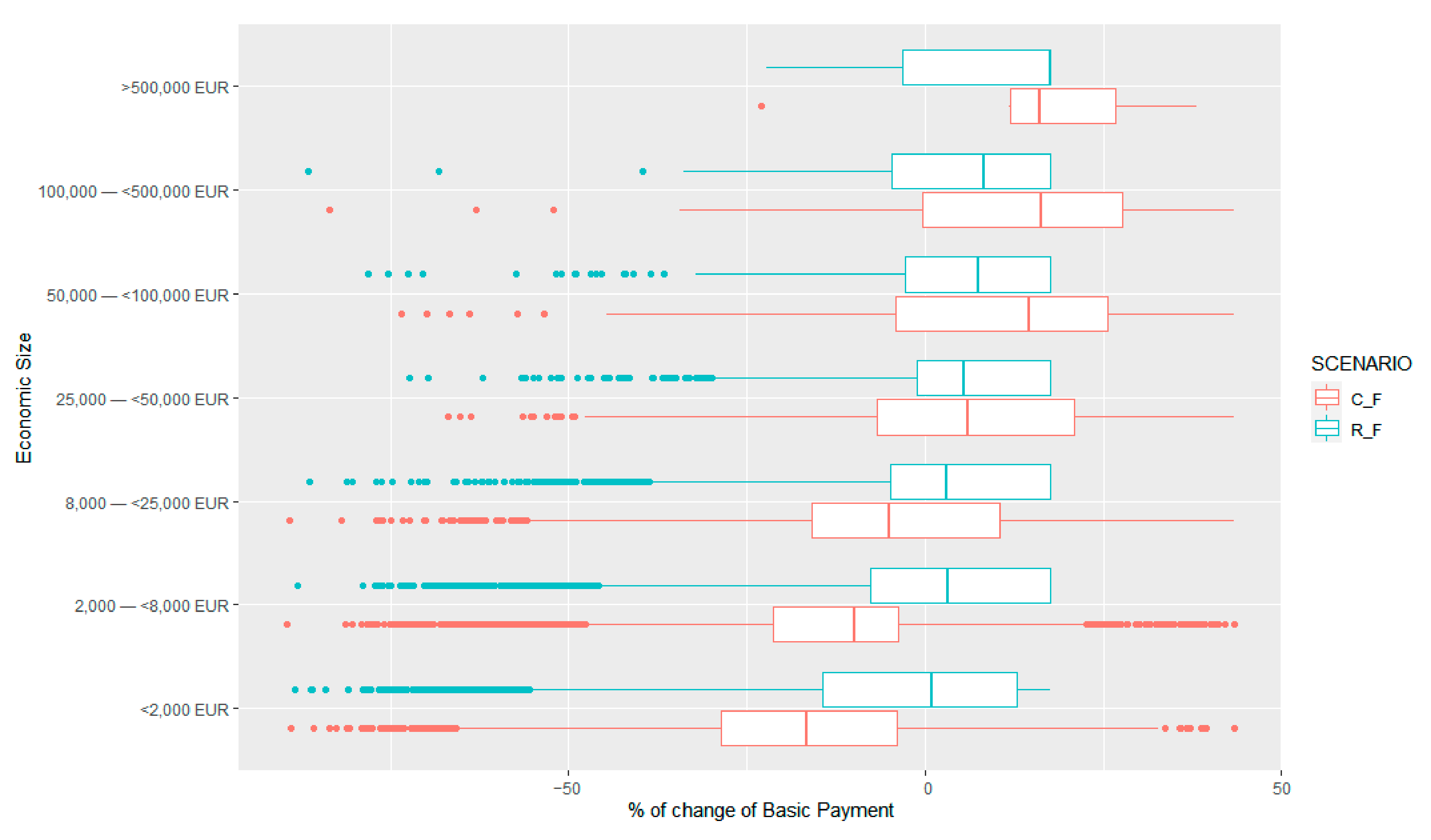

We present the distribution of the above effects across farms in

Figure 1. The distributional information is more useful. While the presentation of the results in economic size categories sums negative and positive effects, the distributional view allows one to see the number of farms and the intensity of the effects for farms that lose and gain. Indeed, for small farms (economic sizes of less than 8000 euros), the countrywide flat rate results in losses to almost all farms, while the regional flat rate has significantly milder effects, with the median of the loss/gain distribution being above 0 (i.e., the majority of the farms do not sustain losses).

Regarding the effects of abolishment on the different types of farming, as shown in

Table 6, certain sectors, like tobacco, other grapes and other permanent crops, will face a significant decrease of payments. The livestock sector will in general receive increased payments. Again, the regional flat rate leads to milder budgetary transfers

We present the distribution of the effects of the abolishment of historical entitlements for different types of farming in

Figure 2. Here it is more apparent that the regional flat rate has significantly more moderate results compared to the countrywide flat rate. Especially for sectors like olives, wine and other permanent crops, while with the countrywide flat rate there are losses for the majority of farms, with the regional flat rate the losses are quite limited.

In

Table 7, we present the results of the combination of abolishing or not abolishing historical entitlements with the two redistribution payment scenarios for different economic sizes. In general, redistribution, as expected, results in the transfer of funds from large to small farms. When more farms are included in the redistribution (R_many), the budget transfer is not as intense as in the case where fewer farms receive it (R_few). In the partial convergence scenario (C85), the redistribution effect is quite strong and results in large farms losing more than 10% of the budget. If historical entitlements are abolished (C_F and R_F) and are combined with a redistribution scenario, we get more smooth budgetary changes. Specifically, when the redistributive budget is focused more on the smaller farms (R_few), those farms either have minimal losses or even gains, in contrast to the current CAP.

In

Figure 3, we present the distribution of the effects of the above combinations. The columns contain the convergence or the abolishment scenarios, the rows the different redistribution scenarios. Each policy option is a combination of the two. For example, in the first cell of the figure, we show the policy option of continuing convergence (C85) and of providing redistribution to a few small farms (Red_few). The red line in the figure is a visual indication of the 0% losses or gains of a scenario. In general, the Red_few scenario results in some small farms having gains but it does not improve the position of the majority of small farms. This effect can be seen in the ‘2000–8000’ EUR economic size, where the median of Red_many is higher than that of Red_few in all scenarios.

In

Table 8, we present the same results but in relation to the different type of farming. In general, the regional flat rate gives smoother budget transfers between farm types and redistribution has mixed effects; sometimes it makes budgetary transfers lower and other times it makes them higher. However, there are sectors that will be negatively impacted in the majority of the scenarios, e.g., tobacco, grapes and citrus. The livestock sector will have budgetary gains in any of the scenarios.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The abolishment of historical entitlements will lead to a loss of income for small farms. In order to evaluate the impact of this loss we have compiled the average farm income from the FADN public database and the lower quantile (Q25) of the payment changes from our simulations (

Table 9).

For small farms (economic size of 2000–8000 euros), the losses are around 3–5% of the net farm income. For example, the highest losses are in the “Countrywide Flat Rate + Redistribution few” scenario. Twenty-five percent of the small farms will have a loss of more than 250 euros where the average net farm income is 4891 euros. For farms of 8000 to 25,000 euros, in the same scenario, 25% of the farms would have a loss of more than 684 euros, where the average net income is 10,819. The reader should have in mind that for Greek farms, CAP payments are often used as working capital, either directly or as bank collateral, for covering the variable costs of the production year (seeds, fertilizers, etc.). Whether these losses are significant and will lead to farms shutting down requires more data. First, the FADN income estimates are mean values and it is possible that there are farms with even lower incomes. It also depends on whether a small farm belongs to a full-time or a part-time farmer; in the latter case, the off-farm income may compensate for the small reductions in CAP payments. In any case, the abolishment of historical entitlements will lead to small farms either reducing the variable costs and/or shutting down, without being able to quantify the latter.

The exit of small farms may have wider impacts in the socio-economic fabric. Davidova et al. [

18] argue that very small farms correspond to poor rural households and thus their agricultural income is a kind of ‘social buffer’. In addition, small farms mainly practice mixed farming, which provides biodiversity ecosystem services. From the food system perspective, Rivera et al. [

19] found that in the EU there are cases where small farms make important contributions both to production and to local food availability. In Greece, almost 35% of the farms belong to farms with an economic size of less than 8000 euros; thus, the argument of Rivera needs to be taken into account.

The above discussion highlights the compromise that policy makers need to consider regarding the abolishment of the historical entitlements in the new CAP strategic plan. On one hand, the EU-related political target of a uniform payment per hectare and, on the other hand, the CAP objectives of ‘ensuring viable income’ and ‘jobs and growth in rural areas’.

Our results show that the policy makers can utilize the redistribution tool to achieve the desired compromise. However, its configuration can be quite complex. For example, different payments per hectare for different areas of land (e.g., one level of payment per hectare for the first two hectares and another one for the next two hectares, etc.). For this, a more detailed quantitative model is required for planning the redistribution measure; for instance, a goal-programming model that will determine the optimum configuration of land breaks and payments based on policy objectives (e.g., the decrease up to a limit for certain farm groups, the payment of a certain percentage of the redistribution budget to the smallest farms, etc.). The model will be constrained by the available budget.

Beyond the redistribution approach, the inclusion of both Pillar I and Pillar II in the new CAP strategic approach allows for greater flexibility. Policy makers could use rural development funds to compensate for any negative income effects on small farms. In addition, they could direct some of the coupled payment support to target sectors that will face income loss with the abolishment of historical entitlements. To conclude, we have shown that although the abolishment of historical entitlements is a desired and reasonable option in the Greek case, it may have negative implications for small farms and certain farming sectors. More data is required in order to gain insights into the impact of this income loss. Nevertheless, the redistribution scheme, now known as complementary income support, can be configured properly so that any problems can be alleviated. This configuration requires a more accurate quantitative model that will cater for the complexity of the redistribution intervention.