Does Entrepreneur Moral Reflectiveness Matter? Pursing Low-Carbon Emission Behavior among SMEs through the Relationship between Environmental Factors, Entrepreneur Personal Concept, and Outcome Expectations

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development of the Study

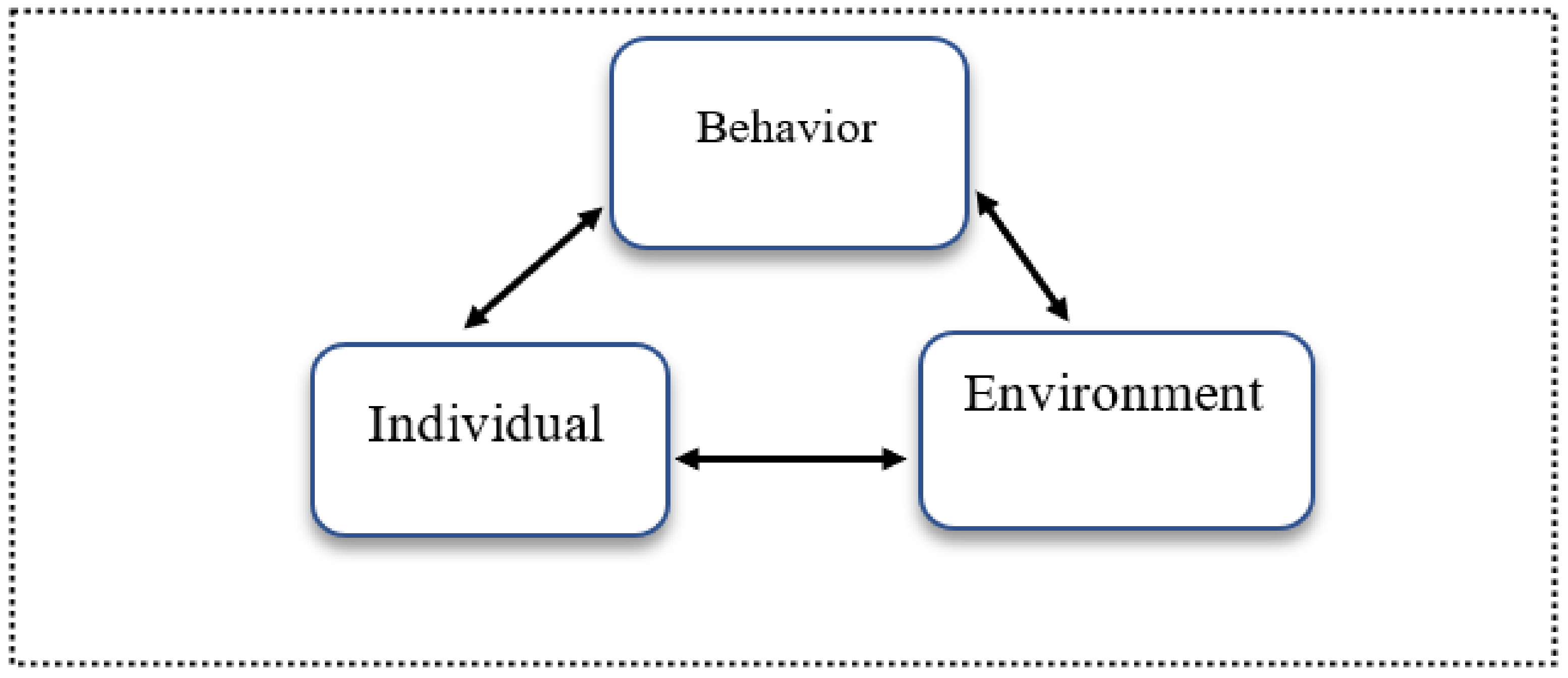

2.1. Social Cognitive Theory (SCT)

2.2. Environmental Influence and Entrepreneur Low-Carbon Behavior

2.2.1. Climate Change Influence and Entrepreneur LCB

2.2.2. Public Media Influence and Entrepreneur LCB

2.2.3. Corporate Social Responsibility Influence and Entrepreneur LCB

2.3. Entrepreneur Personal Self-Concepts and Low-Carbon Behavior

2.3.1. Entrepreneur Green Production Self-Efficacy and LCB

2.3.2. Entrepreneur Self-Monitoring and GPS

2.3.3. Entrepreneur Self-Esteem and GPS

2.3.4. Entrepreneur Self-Esteem and GPS

2.4. Entrepreneur Outcome Expectations and Entrepreneur LCB

2.5. The Moderating Effect of Moral Reflectiveness (EMR)

2.6. Conceptual Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Procedures

3.2. Construct Operationalization

3.2.1. Environmental Influence

3.2.2. Entrepreneur Personal-Concept

3.2.3. Entrepreneur Personal-Concept

3.2.4. Entrepreneur Moral Reflectiveness

3.2.5. Entrepreneur Low-Carbon Behavior

3.3. Method of Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Profile of Participants

4.2. Validity and Reliability Assessment of the Model

4.3. Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT)

4.4. Bias

4.5. Assessment of the Structural Equation Model

4.6. Structural Equation Modelling-Path Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions, Research Implication, and Future Direction

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Theoretical Implications

6.3. Practical Implications

6.4. Limitation and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iqbal, S.; Akhtar, S.; Anwar, F.; Kayani, A.J.; Sohu, J.M.; Khan, A.S. Linking green innovation performance and green innovative human resource practices in SMEs; a moderation and mediation analysis using PLS-SEM. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ur, H.M.R.; Asim, S. Impact of Entrepreneurial Leadership on Innovative Work Behavior: Examining Mediation and Moderation Mechanisms. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2020, 13, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ali, K.A.; Ahmad, M.I.; Yusup, Y. Issues, impacts, and mitigations of carbon dioxide emissions in the building sector. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhao, R.; Chuai, X.; Xiao, L.; Cao, L.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Q.; Yao, L. China’s pathway to a low carbon economy. Carbon Balance Manag. 2019, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kirton, J. BRICS Climate Governance in 2020. 2020. Available online: http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/biblio/Kirton_BRICS_Climate_Governance_2020.html (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Su, J.; Pan, Y. Impact of Stakeholder Behavior on the Carbon Emission Reduction in Supply Chain. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Advanced Education, Management and Humanities (AEMH 2019), Wuhan, China, 19–21 July 2019; Volume 352, pp. 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gifford, R.; Kormos, C.; Mcintyre, A. Behavioral dimensions of climate change: Drivers, responses, barriers, and interventions. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2011, 2, 801–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grottera, C.; La Rovere, E.L.; Wills, W.; Pereira, A.O. The role of lifestyle changes in low-emissions development strategies: An economy-wide assessment for Brazil. Clim. Policy 2020, 20, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, T.J.; McMullen, J.S. Toward a theory of sustainable entrepreneurship: Reducing environmental degradation through entrepreneurial action. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 50–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, F.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, Y. How Does Policy Perception Affect Green Entrepreneurship Behavior? An Empirical Analysis from China. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2021, 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Zhou, R.; Anwar, M.A.; Siddiquei, A.N.; Asmi, F. Entrepreneurs and environmental sustainability in the digital era: Regional and institutional perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eliyana, A.; Musta’in, A.R.S.; Sridadi, A.R.; Widiyana, E.U. The role of self-efficacy on self-esteem and entrepreneurs achievement. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraj, E.; Martinez, E. Environmental values and lifestyles as determining factors of ecological consumer behaviour: An empirical analysis. J. Consum. Mark. 2006, 23, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilg, A.; Barr, S.; Ford, N. Green consumption or sustainable lifestyles? Identifying the sustainable consumer. Futures 2005, 37, 481–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.Y.; Hsu, M.H. Using Social Cognitive Theory to Investigate Green Consumer Behavior. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2015, 24, 326–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niamir, L.; Filatova, T.; Voinov, A.; Bressers, H. Transition to low-carbon economy: Assessing cumulative impacts of individual behavioral changes. Energy Policy 2018, 118, 325–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Cultivate Self-efficacy for Personal and Organizational Effectiveness. In The Blackwell Handbook of Principles of Organizational Behaviour; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England Bayrón, C. Social Cognitive Theory, Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Entrepreneurial Intentions: Tools to Maximize the Effectiveness of Formal Entrepreneurship Education and Address the Decline in Entrepreneurial Activity. Rev. Griot (Etapa IV-Colección Complet. 2013, 6, 66–77. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea, D.; Buckley, F.; Halbesleben, J.; Gibbs, D.; O’Neill, K.; Wei, C.F.; Yu, J.; Huang, T.L.; Brando-Garrido, C.; Montes-Hidalgo, J.; et al. Self-regulation in entrepreneurs: Integrating action, cognition, motivation, and emotions. Emerg. Econ. Transform. Int. Bus. Brazil, Russ. India China 2020, 10, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams Middleton, K. Developing Entrepreneurial Behavior: Facilitating Nascent Entrepreneurship at the University; Chalmers University of Technology: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ojo, A.O.; Alias, M. Conceptualising Social Media Entrepreneurial Engagement from the Socio-Cognitive Theory. J. Entrep. Res. Pract. 2021, 2021, 846138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.J.; Guerrero, M.D. Social cognitive theory. In Routledge Handbook of Adapted Physical Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; Volume 6, pp. 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Sung, C.S. Does social media use influence entrepreneurial opportunity? A review of its moderating role. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luthans, F.; Stajkovic, A.D.; Ibrayeva, E. Environmental and psychological challenges facing entrepreneurial development in transitional economies. J. World Bus. 2000, 35, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miranda, I.T.P.; Moletta, J.; Pedroso, B.; Pilatti, L.A.; Picinin, C.T. A Review on Green Technology Practices at BRICS Countries: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211013780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations The Paris Agreement | United Nations. 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/paris-agreement (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- IPCC Global Warming of 1.5 °C. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- United Nations Climate Reports | United Nations. 2020. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/reports (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- United Nation Climate Change COP26 Reaches Consensus on Key Actions to Address Climate Change | UNFCCC. Available online: https://unfccc.int/news/cop26-reaches-consensus-on-key-actions-to-address-climate-change (accessed on 27 November 2021).

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jain, V.K.; Gupta, A.; Tyagi, V.; Verma, H. Social media and green consumption behavior of millennials. J. Content Community Commun. 2020, 10, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Luo, S. Consumers’ intention and cognition for low-carbon behavior: A case study of Hangzhou in China. Energies 2020, 13, 5830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caitlyn Loeffler, B. What Are the Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility Initiatives on; Georgetown University: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, T.; Liu, Q.; Chen, S.; Wang, S.; Lai, K.K. Pricing decisions of CSR closed-loop supply chains with carbon emission constraints. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sampene, A.K.; Li, C.; Agyeman, F.O.; Robert, B.; Moses, S.; Salomon, A.A. A Critical assessment of the role of Entrepreneurship. Eur. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2021, 9, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Buendía-Martínez, I.; Monteagudo, I.C. The role of CSR on social entrepreneurship: An international analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, O.; Shepherd, D.A. Different Strokes for Different Folks: Entrepreneurial Narratives of Emotion, Cognition, and Making Sense of Business Failure. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 375–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ceresia, F.; Mendola, C. Am I an Entrepreneur? Entrepreneurial Self-Identity as an Antecedent of Entrepreneurial Intention. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbery, R.; Lean, J.; Moizer, J.; Haddoud, M. Entrepreneurial identity formation during the initial entrepreneurial experience: The influence of simulation feedback and existing identity. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 85, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brando-Garrido, C.; Montes-Hidalgo, J.; Limonero, J.T.; Gómez-Romero, M.J.; Tomás-Sábado, J. Relationship of academic procrastination with perceived competence, coping, self-esteem and self-efficacy in Nursing students. Enfermería Clínica (Engl. Ed.) 2020, 30, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Obschonka, M.; Schwarz, S.; Cohen, M.; Nielsen, I. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: A systematic review of the literature on its theoretical foundations, measurement, antecedents, and outcomes, and an agenda for future research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 110, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. How Does Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy Influence Innovation Behavior? Exploring the Mechanism of Job Satisfaction and Zhongyong Thinking. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Lin, C.; Zhao, G.; Zhao, D. Research on the effects of entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial self-efficacy on college students’ entrepreneurial intention. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karoly, P.; Kanfer, F.H. Self-control: A behavioristic excursion into the lion’s den. Behav. Ther. 1972, 3, 398–416. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea, D.; Buckley, F.; Halbesleben, J. Self-regulation in entrepreneurs: Integrating action, cognition, motivation, and emotions. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 7, 250–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hernández, Y.C.U.; Cueto, O.F.A.; Shardin-Flores, N.; Luy-Montejo, C.A. Academic procrastination, self-esteem and self-efficacy in university students: Comparative study in two peruvian cities. Int. J. Criminol. Sociol. 2020, 9, 2474–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pautina, M.R.; Puluhulawa, M.; Djibran, M.R. The Correlation Between Interest In Entrepreneurship And Students’ Self-Esteem. J. Bus. Behav. Entrep. 2018, 2, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elazar, Y. Adam Smith on impartial patriotism. Rev. Polit. 2021, 83, 329–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veljkovic, S.M.; Maric, M.; Subotic, M.; Dudic, B. Family Entrepreneurship and Personal Career Preferences as the Factors of Di ff erences in the Development of Entrepreneurial Potential of Students. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wei, C.F.; Yu, J.; Huang, T.L. Exploring the drivers of conscious waste-sorting behavior based on sor model: Evidence from Shanghai, China. In Proceedings of the 2020 Management Science Informatization and Economic Innovation Development Conference (MSIEID), Guangzhou, China, 18–20 December 2020; pp. 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandstätter, H. Personality aspects of entrepreneurship: A look at five meta-analyses. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2011, 51, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luc, P.T. Outcome expectations and social entrepreneurial intention: Integration of planned behavior and social cognitive career theory. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, E.W.; Bendickson, J.S.; McDowell, W.C. Revisiting entrepreneurial intentions: A social cognitive career theory approach. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2018, 14, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.C.; Unidos, E.; Liguori, E.W.; Unidos, E. How and when is self-efficacy related to entrepreneurial intentions: Exploring the role of entrepreneurial outcome expectations and subjective norms. Revista de Estudios Empresariales. Segunda Época 2019, 1, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Ullah, Z.; Mahmood, A.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Han, H.; Scholz, M. Corporate social responsibility at the micro-level as a “new organizational value” for sustainability: Are females more aligned towards it? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PAGE Partnership for Action on Green Economy (PAGE) Jiangsu Province, China (2015-2020)—Greenjobs AP. Available online: https://apgreenjobs.ilo.org/project/copy2_of_greener-business-asia/partnership-for-action-on-green-economy-page-jiangsu-province-china-2015-2020 (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- Dong, K.; Sun, R.; Hochman, G. Do natural gas and renewable energy consumption lead to less CO2 emission? Empirical evidence from a panel of BRICS countries. Energy 2017, 141, 1466–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Kubota, J.; Han, R.; Zhu, X.; Lu, G. Does urbanization lead to more carbon emission? Evidence from a panel of BRICS countries. Appl. Energy 2016, 168, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Impeding ecological sustainability through selective moral disengagement. Int. J. Innov. Sustain.Dev. 2007, 2, 8–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enuoh, R.; Pepple, G.J.; Cross, C.; State, R.; Etim, G.S.; Bassey, A. Green entrepreneurship and business performance in Nigeria: A conceptual review. Solid State Technol. 2021, 63, 15767–15775. [Google Scholar]

- Alwakid, W.; Aparicio, S.; Urbano, D. The influence of green entrepreneurship on sustainable development in Saudi Arabia: The role of formal institutions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Nsiah, T.K.; Charles, O.; Ayisi, A.L. Credit risk, operational risk, liquidity risk on profitability. A study on South Africa commercial Banks. A PLS-SEM Analysis. Rev. Argentina Clínica Psicológica 2020, XXIX, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Fangwei, Z.; Siddiqi, A.F.; Ali, Z.; Shabbir, M.S. Structural Equation Model for evaluating factors affecting quality of social infrastructure projects. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed, M.; Polas, H. The effects of individual characteristics on women intention to become social entrepreneurs? J. Public Aff. 2020, 21, e2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Using Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in International Advertising Research: Basic Concepts and Recent Issues. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233408729_Using_Partial_Least_Squares_Path_Modeling_in_International_Advertising_Research_Basic_Concepts_and_Recent_Issues (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- Harman, H.H. Modern Factor Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago IL, USA, 1976; ISBN 0226316521. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayati, P.; Wulandari, D.; Eko, B.; Wibowo, A. Heliyon Does entrepreneurship education promote vocational students ’ entrepreneurial mindset? Heliyon 2020, 6, e05426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y.; Singh, S. On the use of structural equation models in experimental designs: Two extensions. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1991, 8, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS Path Modeling in New Technology Research: Updated Guidelines. 2016. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382/full/pdf (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Marcoulides, G.A.; Chin, W.W.; Saunders, C. A critical look at partial least squares modeling. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiang, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Li, G. Golden apples or green apples? The effect of entrepreneurial creativity on green entrepreneurship: A dual pathway model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.M.; Ou, S.J. Research on low-carbon behavioural identity with the New Environmental Paradigm Scale. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 267, 022014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.W.; Su, Z.Y.; Huang, C.W.; Shadiev, R. The influence of environmental, social, and personal factors on the usage of the app “Environment Info Push”. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, L.; Xu, Y.; Liu, G.; Wang, T.; Du, C. Understanding Firm Performance on Green Sustainable Practices through Managers’ Ascribed Responsibility and Waste Management: Green Self-Efficacy as Moderator. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liao, H.-Y.; Hsu, C.-T.; Chiang, H.-C. How does green intellectual capital influence employee pro-environmental behavior? The mediating role of corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 2, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Green creative behavior in the tourism industry: The role of green entrepreneurial orientation and a dual-mediation mechanism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1290–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, C. 10 Actions That Companies Can Put in Place to Fight Climate Change. Available online: https://youmatter.world/en/actions-companies-climate-change-environment-sustainability/ (accessed on 19 November 2021).

| Background Information | Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 685 | 67% |

| Female | 330 | 33% | |

| Age of SMEs | <1 Year | 95 | 9% |

| 1–5 Years | 257 | 25% | |

| 6–10 Years | 360 | 35% | |

| 11–15 Years | 273 | 27% | |

| >15 Years | 30 | 3% | |

| Industrial Sector | High-Tech | 32 | 3% |

| Green technology Enterprise | 65 | 6% | |

| Services | 110 | 11% | |

| Manufacturing | 553 | 54% | |

| Construction | 221 | 22% | |

| Others | 34 | 3% | |

| Number of Employees | 5–30 Workers | 115 | 11% |

| 31–50 Workers | 240 | 24% | |

| 51–100 Workers | 422 | 42% | |

| More than 100 Workers | 238 | 23% |

| Variables/Indicators | Items | Outer Loadings | CA (α > 0.7) | Rho_A (>0.7) | CR (ρc) (>0.7) | AVE (>0.5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC1 | 0.770 | 0.880 | 0.934 | 0.911 | 0.680 | |

| CC2 | 0.851 | |||||

| Climate Change Influence (CC) | CC3 | 0.939 | ||||

| CC4 | 0.914 | |||||

| CC5 | 0.895 | |||||

| PM1 | 0.810 | 0.906 | 0.912 | 0.930 | 0.726 | |

| PM2 | 0.860 | |||||

| Public Media Influence (PM) | PM3 | 0.846 | ||||

| PM4 | 0.853 | |||||

| PM5 | 0.889 | |||||

| SR1 | 0.761 | 0.898 | 0.899 | 0.925 | 0.713 | |

| SR2 | 0.832 | |||||

| Social Responsibility (SR) | SR3 | 0.875 | ||||

| SR4 | 0.873 | |||||

| SR5 | 0.874 | |||||

| SM1 | 0.737 | 0.838 | 0.851 | 0.880 | 0.559 | |

| SM2 | 0.841 | |||||

| Entrepreneur Self-Monitor (SM) | SM3 | 0.877 | ||||

| SM4 | 0.851 | |||||

| SM5 | 0.833 | |||||

| SM6 | 0.852 | |||||

| SP1 | 0.822 | 0.798 | 0.820 | 0.864 | 0.566 | |

| SP2 | 0.857 | |||||

| Entrepreneur Self-Pref. (SP) | SP3 | 0.856 | ||||

| SP4 | 0.825 | |||||

| SP5 | 0.804 | |||||

| SE1 | 0.821 | 0.889 | 0.906 | 0.916 | 0.645 | |

| SE2 | 0.854 | |||||

| Entrepreneur Self-Esteem (SE) | SE3 | 0.864 | ||||

| SE4 | 0.858 | |||||

| SE5 | 0.715 | |||||

| SE6 | 0.861 | |||||

| GPS1 | 0.738 | 0.815 | 0.835 | 0.868 | 0.530 | |

| GPS2 | 0.855 | |||||

| Green Prod. Self-efficacy (GPS) | GPS3 | 0.762 | ||||

| GPS4 | 0.819 | |||||

| GPS5 | 0.825 | |||||

| GPS6 | 0.808 | |||||

| POE1 | 0.717 | 0.896 | 0.896 | 0.921 | 0.660 | |

| POE2 | 0.768 | |||||

| Personal Outcome Exp. (POE) | POE3 | 0.815 | ||||

| POE4 | 0.863 | |||||

| POE5 | 0.845 | |||||

| POE6 | 0.856 | |||||

| EGO1 | 0.884 | 0.838 | 0.940 | 0.862 | 0.515 | |

| EGO2 | 0.814 | |||||

| EGO3 | 0.822 | |||||

| Green Prod. Out. Exp. (EGO) | EGO4 | 0.789 | ||||

| EGO5 | 0.781 | |||||

| EGO6 | 0.870 | |||||

| LCB1 | 0.836 | 0.889 | 0.891 | 0.916 | 0.644 | |

| LCB2 | 0.842 | |||||

| Low-Carbon Behavior (LCB) | LCB3 | 0.806 | ||||

| LCB4 | 0.757 | |||||

| LCB5 | 0.772 | |||||

| LCB6 | 0.799 |

| CC | EGO | GPS | LCB | PM | POE | SE | SM | SP | SR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | ||||||||||

| EGO | 0.877 | |||||||||

| GPS | 0.577 | 0.816 | ||||||||

| LCB | 0.299 | 0.545 | 0.862 | |||||||

| PM | 0.290 | 0.621 | 0.936 | 0.708 | ||||||

| POE | 0.317 | 0.528 | 0.762 | 0.943 | 0.785 | |||||

| SE | 0.296 | 0.575 | 0.912 | 0.972 | 0.969 | 0.877 | ||||

| SM | 0.942 | 0.986 | 0.754 | 0.471 | 0.524 | 0.464 | 0.492 | |||

| SP | 0.647 | 0.721 | 0.745 | 0.765 | 0.627 | 0.866 | 0.690 | 0.709 | ||

| SR | 0.310 | 0.480 | 0.693 | 0.895 | 0.689 | 0.984 | 0.805 | 0.427 | 0.880 |

| Construct | R2 | Adj R2 | VIF | Q2 | F2 | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCB | 0.975 | 0.975 | 1.846 | 0.413 | 0.037 | 0.042 |

| GPS | 0.958 | 0.958 | 1.424 | 0.402 |

| Hypothesis Path | (β) | T Statistics | P-Stats | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Relationship | |||||

| H1 | Climate Change Influence-> Entrepreneur LCB | 0.661 | 10.436 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2 | Public Media Influence -> Entrepreneur LCB | 1.795 | 12.956 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3 | Entrepreneur Social Responsibility-> LCB | 1.807 | 13.375 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H4 | Green Production Self-efficacy -> Entrepreneur LCB | 0.362 | 11.525 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H5 | Entrepreneur Self-monitoring-> Green Production Self-efficacy | 0.367 | 17.639 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H6 | Entrepreneur Self-esteem -> Green Production Self-efficacy | 0.817 | 50.238 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H7 | Entrepreneur Self-preference-> Green Production Self-efficacy | −0.103 | 7.584 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H8 | Personal Outcome Expectation-> Entrepreneur LCB | −1.061 | 7.843 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H9 | Green prod. Outcome Expectation-> Entrepreneur LCB | −0.315 | 9.409 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Indirect/Moderating Path | |||||

| H10 H11 | EMR*EGO -> LCB EMR*POE -> LCB | 0.673 0.601 | 10.521 10.340 | 0.000 0.000 | Supported Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cai, L.; Kwasi Sampene, A.; Khan, A.; Oteng-Agyeman, F.; Tu, W.; Robert, B. Does Entrepreneur Moral Reflectiveness Matter? Pursing Low-Carbon Emission Behavior among SMEs through the Relationship between Environmental Factors, Entrepreneur Personal Concept, and Outcome Expectations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 808. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020808

Cai L, Kwasi Sampene A, Khan A, Oteng-Agyeman F, Tu W, Robert B. Does Entrepreneur Moral Reflectiveness Matter? Pursing Low-Carbon Emission Behavior among SMEs through the Relationship between Environmental Factors, Entrepreneur Personal Concept, and Outcome Expectations. Sustainability. 2022; 14(2):808. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020808

Chicago/Turabian StyleCai, Li, Agyemang Kwasi Sampene, Adnan Khan, Fredrick Oteng-Agyeman, Wenjuan Tu, and Brenya Robert. 2022. "Does Entrepreneur Moral Reflectiveness Matter? Pursing Low-Carbon Emission Behavior among SMEs through the Relationship between Environmental Factors, Entrepreneur Personal Concept, and Outcome Expectations" Sustainability 14, no. 2: 808. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020808