2. Defining Best Practices

A best practice is a term that is thought to have originated from the business and finance sector in the 1960s [

1]. The term denotes a procedure or working method that produces a desired or most efficient result (often a product), and has therefore become a preferred standard within an industry. Some best practices have undergone a rigid trial-and-error process, and are expounded by an authority or expert body to become an accepted or recommended practice, or just the best way to do things compared to an alternative. They have been demonstrated to improve people’s quality of life and can be evidence-based practices that have worked in diverse situations in a variety of settings. The terminology has now been adopted in various fields and professions, such as construction, marketing, healthcare and human service fields, even in heritage management.

In the field of heritage management, defining ‘best practices’ raises several dilemmas [

2], in particular when we look at the social dimension of heritage. Contemporary heritage management is not just about material buildings, objects and sites, but primarily about

people and their values. This prioritising of the living population makes it almost impossible to have a standardised approach; what works for one community, or in one region or heritage site may not apply to another context under different circumstances. There are also issues with who—which authority and in what political climate—decides what a best practice is. While certain aspects of heritage management require experts when dealing with technical aspects of conservation, ethical issues may arise if a (set of) best practice(s) is accepted by a governing organisation that has not taken fully into account the full spectrum of stakeholders involved in heritage management. This raises the question of who benefits from a particular approach and who may even be (emotionally, socially, economically) damaged by it. Likewise, the term ‘highest standards’ that are celebrated through awards are subject to shifting paradigms in a discipline that is rapidly changing. Intrinsic heritage values expounded by experts, such as historic or artistic values, that long dominated heritage management, have now made way for more instrumental values [

3] such as economic, social/community and environmental values.

However, just because it is nearly inconceivable to adopt a best practice that offers a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach, the cultural heritage field does have ample examples of practices that can be called inspirational. The European Cultural Heritage Strategy for the 21st Century of the Council of Europe (CoE) promotes a “shared and unifying approach to cultural heritage management” [

4], and collects examples that are renamed ‘good practices’, indicating that there is no one ‘best’ method or action. It focuses on three components: a social component, a territorial and economic component, and a knowledge and education component. Rather than following a generic framework of best practices, perhaps developing a tailor-made approach unique to each site or community is a ‘good or ‘inspirational practice’ [

1].

Acknowledging that there is no fixed definition of a ‘best practice’ in heritage management, where values are approached reflexively to be more inclusive, which criteria must the nominations then meet to be considered for an award or prize? On the website of the Europa Nostra Awards, in the

About section, the function of the awards is to “celebrate and promote the highest standards” in the field of heritage [

5]. It unfortunately does not further define or elaborate what those standards are, while it does display the awards as a catalogue of ‘best practices’.

It further reads:

“The Awards provide a wide-ranging portfolio of high-quality examples which help to illustrate best practices and promote the exchange of ideas and approaches. The Awards scheme constitutes a rich database of best practices in heritage, which are geographically and thematically diverse. This database is also widely used for research purposes.”

The EAA Heritage Prize webpage also contains little information on what it considers good practices, except that the main aim of the prize is to reward individuals or organisations for their “outstanding contribution to either the protection or presentation of European archaeological heritage” [

6].

Before delving further into the question of criteria, a brief outline for the two major heritage awards must be given.

4. Analysis

A conceptual content analysis was applied to analyse the results of the winners of both the Europa Nostra Awards and the EAA Heritage Prize in the period from 2015 to 2020. In the case of Europa Nostra these were 168 awards, for the EAA we included eleven prizes. We worked with public information from the websites. First the award category, the type of heritage and the values mentioned in the justifications were identified and counted. We also looked at the locations where the heritage or winner originated from, the audiences targeted (if applicable) and at the gender ratio of both award recipients and judges. We developed the categories interactively, during the analysis. Then a deeper analysis of the content was applied to place the aforementioned types and values into context and identify if patterns and perhaps trends are detectable.

It must be stressed that based on the information given on the websites, it was at times difficult to assess why some nomination projects received an award while others did not. When inquiring about the nomination dossiers via e-mail, Europe Nostra first agreed to send the files, but none were received after repeated gentle requests. The EAA was approached to provide nomination dossiers as well, but this request was denied too due to issues with privacy. Information on its award winners and their laudations were also retrieved from the website.

4.1. What Wins?

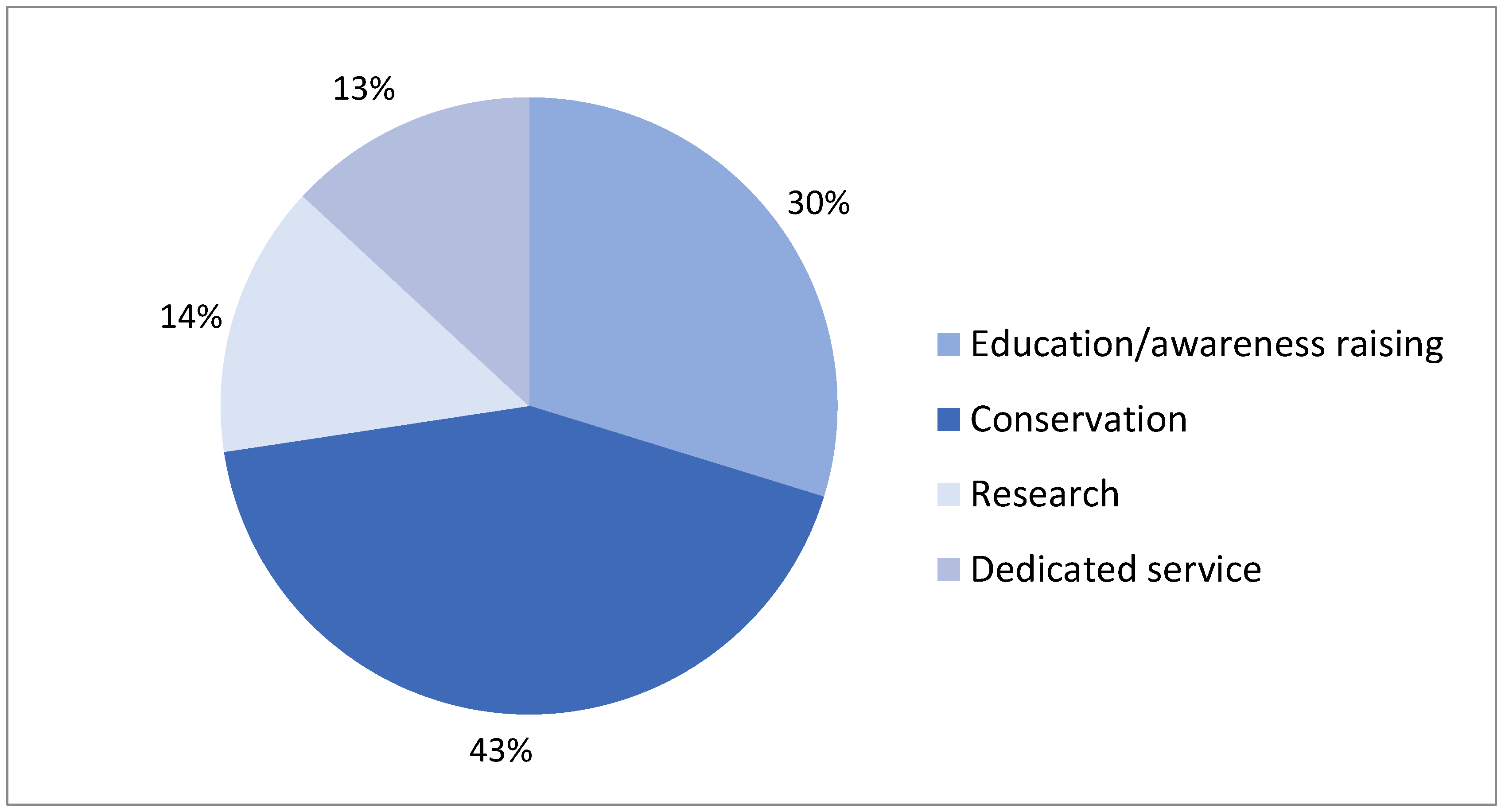

In the past six years (2015–2020) Europa Nostra awarded most awards (72) in the category of conservation (

Figure 1), with education and awareness raising following at quite a distance (50 awards). This may suggest that conservation efforts are a prevailing and dominant practice, with presumably the largest number of nominations. This focus on conservation also suggests it to be the heritage practice that is valued most by the awarding organisation. It may also mean the heritage domain has been most successful in developing best practices in conservation, as this has been a focal point of heritage practices since the ICOMOS Venice Charter was introduced in 1964 as a guideline for good practice for restoring monuments and sites [

18]. Perhaps it even reflects that defining and acknowledging good practices is easier or more straightforward for working with material than working with people (e.g., in education). We can however see a slightly decreasing dominance of this focus on conservation across the years (

Figure 2), with 2020 being an anomaly, as the number of awards was much smaller in this period (possibly due to the COVID-19 pandemic).

The EAA Heritage Prizes can be categorized in individual or institutional categories. However, this is a new categorisation that was initiated as of 2018. Up and including 2018, most of the winners were individuals. Between the period 2015–2020 seven individuals received the prize, and four were given to collectives. All of the recipients had two or more overlapping criteria, of which heritage was mentioned the most (

Figure 3).

4.2. Type of Heritage

By examining the Europa Nostra Awards, we found that there is a wide variety of types of heritage represented in the awarded practices (

Figure 4). Providing a distinctive categorization is a challenge, however, as many heritage projects relate to more than one type of heritage. We based the classification therefore on characterizations provided by the nomination texts, instead of on our own predefined categories, and classified most projects in multiple categories. Built heritage, consisting of historic buildings (and the subcategory of architecture) clearly stand out as a main category. It was followed by the category of intangible heritage, for which it was observed that quite a large part was connected with built heritage. Only just over half (56%) of this category of intangible heritage—47 awarded practices—related to intangible heritage exclusively. There is thus clearly less attention for intangible forms of heritage if it is not connected with built heritage.

Objects are third in line and obviously the subjects of many awarded heritage practices as well. Crafts and skills, as a subcategory of intangible heritage, receives quite some attention as well. This division also shows the categories that were least addressed by these good practices in this particular time period; maritime heritage, archaeology, green heritage (e.g., historical parks and gardens), military heritage, heritage of infrastructure and transportation, and heritage relating to subsistence and food production.

For the EAA Heritage Prize, the division of tangible and intangible seems unreasonable due to the recognition of the EAA jury that both tangible and intangible heritage are deeply interconnected and co-dependent. As Laurajane Smith declared, all heritage is subject to a process of cultural production and always contains an intangible component [

19]. Yet, since archaeology mostly deals with material culture, and the focus seems to be on preservation or protection of tangible remains, the EAA Heritage Prizes can be categorized in only tangible heritage. However, they are subdivided into cultural landscape, archaeological, military, industrial, religious, and Indigenous heritage (

Figure 5). A few winners showed an overlap. Three are also listed as World Heritage Sites. Three prizes were categorized as other since they did not specifically mention a type of heritage.

What is noticeable is that in both award systems, the emphasis on buildings (architecture) and their conservation, restoration and protection is prominent. Another pattern that is detectable in both is that the interconnectedness with intangible heritage is highlighted. This includes various aspects of intangible heritage such as (local) knowledge concerning tangible heritage, identity and traditions and social practice.

4.3. Urban versus Rural Heritage

For the Europa Nostra awards we also looked at locations and whether there was an equal amount of attention for heritage in urban and rural contexts. Of all 112 practices for which the context was explicitly mentioned on the awards webpage, it turned out that a majority (52%) related to heritage assets in an urban context, and 38 per cent showcased rural heritage (

Figure 6). A small group (10%) could not be assigned to just one category. It was noticeable that over the years the share of rural contexts has been diminishing, except in 2019, which showed a reversed pattern (

Figure 7).

Given the strong focus on buildings and architecture, as reflected in the practices that were nominated and awarded, there may thus be more heritage assets, in quantitative terms, in the urban environment. This may be a historically grown inequality, reflecting a society and profession that throughout the past of heritage management valued heritage assets found in urban contexts more than in rural areas and thus safeguarded more of the first than the latter. This inequality in terms of the volume of subjects that can be nominated for a good practice may explain this difference in the awards distribution.

It raises the question of whether there are more opportunities for heritage professionals (e.g., knowledge, skills, capacity and financial means) to develop good practices in an urban context. Additionally, do city dwellers receive more opportunities to benefit from heritage practices than inhabitants of rural and remote places? Since 29.1 per cent of the population in the European Union lived in rural areas in 2018 [

20], the awards distribution suggests that a large group of the population is far less served by heritage activities and as such potentially deprived of the societal benefits associated with such activities. Given the value of heritage as an acknowledged driver of development and of (social) wellbeing, this does not sound like a situation political powers wish for. The European Commission, for instance, already considers the percentage of population at risk of social exclusion and poverty higher in rural and remote areas than in the urban context [

21]. It is therefore most probably not the intention of heritage policies and strategies to make a distinction in favour of urban populations. The latter would need heritage activities with a social or economic dimension just as much as city dwellers.

In the figures on the Europa Nostra awards, an interesting trend is however detectable. For the awards given to eastern European projects, 17% related to a rural environment, 41.5% to an urban context, but the awarded projects in Western Europe related in 28% to a rural context and in 32.5% to a city. This suggests that in the last six years there was at least in a large part of Europe and in the largest amount of prizes a near equal appreciation of heritage practices in both rural and urban contexts.

4.4. Who Wins?

From 2015 until 2020, 168 laureates won the Europa Nostra Awards, of which 25 per cent was located in the geographical eastern part of Europe (for this analysis it included the USSR and its satellite states in the Comecon, and Turkey), 75 per cent west of it. This strong geographical focus on the west is striking. Given that the aim of the awards is to showcase excellence, it suggests there are far fewer good practices in the eastern part of Europe. Even worse is the total absence of several countries in the list of laureates, suggesting they have no appreciated practices at all. An encouraging trend can be noticed, however (

Figure 8); while in 2015 the share of awards for eastern Europe was 17 per cent only, in 2019 and 2020 it had increased to 29 per cent.

Historically, Spain, Italy and the United Kingdom have applied for entry nominations the most and have therefore won the most awards—40% of all nominations in the past 19 years originated from these three countries, and one third of all awards won since 2002 have been won by these three nations. In the ‘facts & figures’ page on the Europa Nostra Award website, it is acknowledged that these three countries have ranked in the top three since 2002 [

22]. It does not come as a surprise that these countries dominate the winners list as well.

It can be seen however, that while in 2015 the share for ‘east’ and ‘west’ was 20 per cent and 80 per cent, respectively, it was one third and two-thirds in 2020. Despite a persisting imbalance, the tendency is toward a declining difference.

Regarding the EAA Heritage Prize, between 2015 and 2020, three awards have gone to Spanish initiatives, three to British recipients. The Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Turkey and Italy each received one prize in the past six years. Additionally, in this case, we can establish that the majority of the prizes are going to Western European states. If we look at all thirty award winning individuals and organisations since 1999, the pattern is even more apparent; 25 recipients come from the western European states, three from eastern European states, one from Turkey, and one went to the Council of Europe which represents all European member states. This does suggest a western bias. Even more striking is the absence of a long list of states which from 1999 to 2020 never made it to the stage. As this prize represents best practices, not getting awards may suggest that these states do not develop or apply highly appreciated practices in archaeology.

It must be stressed that due to the lack of access to nomination files, it cannot be stated with certainty that there is a bias in recognizing best practices from nominations or in the appreciation and subsequent rewarding of practices.

4.5. Gender Diversity

We also looked at the gender of both the jury and the recipients of the awards and prizes. For this, the Europa Nostra Awards website provided more information than the EAA website, therefore the results are not holistic.

From 2015 to 2020 the Europa Nostra awards for dedicated services (21) consisted of eight individuals and 13 organisations (

Figure 9). Only two of these individuals were women (25%). In total, 29 per cent of the awards went to men, 9 per cent to women.

For one particular year, 2019, we looked in more detail at the awards and included the jury gender distribution. This year was selected because we then worked on these awards for the purpose of collecting inspirational examples of European heritage practices fostering social responsibility [

1]. In this year there are 15 men versus 8 women in total in the jury for all four categories. This indicates inequity at the decision-making level. When we disaggregate the data per category, it shows the categories for ‘Education, training and awareness-raising’ consists of three women and two men, and ‘dedicated service’ has an equal number of two per gender. However, the category of ‘Conservation’ is skewed towards a male bias where the jury consists of seven male and two female members. The category of ‘Research’ only has one woman on the jury, compared with four men. Because of the greater inequity in the latter two categories, the overall number of juries is heavily male-dominated.

Looking at the gender distribution of the recipients of all awards in 2019, out of the 27 laureates, 14 awards were bestowed upon men or male leaders of the project, six recipients were women or women-led projects, three projects had an equal gender representation and of four projects data were not included (or maybe not relevant).

When linking the gender data of the winning projects to the gender make-up of the juries, the findings are striking (see

Table 3). Apart from the category of ‘Education, training and awareness-raising’, which shows a more or less gender equal distribution of the awards, in all the other categories, the majority of the awards went to men or men-led projects. Even the category ‘Dedicated service by individual or organisation’, with a gender equal jury, awarded only male-led projects.

When we combine these figures on 2019 with the overall gender distribution (

Figure 9), a consistent gender bias appears. Interestingly the pattern is reversed for ‘education’, a field that has been subject to feminisation, with according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) on average 69.6 per cent of all teachers at all levels being women in 2018 [

23]. This is confirmed by the

Gender gaps in the Cultural and Creative Sectors report of 2020 by The European Expert Network on Culture and Audiovisual (EENCA), which states that across the cultural and creative sectors, there is an inclination towards more women working in educational trajectories [

24]. This development may account for the larger proportion of women as juries in this category, and more awards going to women because they are overrepresented in the field. However, it does not mean that male-led initiatives remain unawarded. This is in stark contrast to the category ‘conservation’ where the male heavy jury have awarded six prizes to men or men-led initiatives. Compared to the category ‘dedicated service’ with a gender equal jury, no women received an award.

Education is not the only field where more women than men are employed. The whole sector of cultural heritage and related professions also sees an overrepresentation of women working in different areas, such as librarians, museum workers, heritage managers, architects and archaeologists to name a few examples [

24,

25]. A survey (in 2015) on workers in the UK information sectors conducted by the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals and the Archives and Records Association [

26] reveals that this workforce is made up of 78.1% of women and only 29.1% of men. The report Discovering the Archaeologists of Europe 2012–14 also shows that across the whole of Europe, at least half (50.7%) of the employees in archaeology are women [

17]. These numbers beg the question of why men receive more awards. We will return to this in the discussion.

The EAA Heritage Prize Committee consists of four to five members who serve a three-year term with the possibility of re-appointment [

27]. So far, most members had been active as former executive board members or in other committees. Using the Wayback Machine of The Internet Archive (web.archive.org, accessed 15 November 2021), we have been able to retrieve who was on the committee from September 2015 until now. During September 2015 to September 2019, the committee consisted of two men and two women. One of the men held the chair of the committee. In September 2019, another woman joined the committee making a total of five members, with the same male chair. Since the start of the prize, no woman has acted as chair.

Looking at the gender ratio of the EAA Heritage Prize winners, a gender equal committee does not guarantee an equitable distribution of prizes among the genders. Excluding the 2015 prizes for which the committee composition could not be accounted for using the Wayback Machine, only two women won a prize in 2016 and in 2020. Two groups whose gender composition is unknown won prizes in 2016 and 2017. From 2018 until 2020, five prizes went to men or men-led projects. Rather than a trend towards gender equality, we see a male bias from 2016 to 2020. Similar to the Europa Nostra Awards, a gender equal jury or committee does not translate into a gender balanced award system.

4.6. Whom Do Best Practices Address?

For both prizes we analysed if the awarded practices addressed specific target audiences and in case of societal engagement, to whom this engagement was directed. In the Europa Nostra Awards, less than a third (29%) of the best practices explicitly mentioned a specific social group that was meant to benefit from the heritage project. The local community was mentioned most, followed by young people (children and students) and volunteers (

Figure 10). This illustrates the importance of the social dimension of these heritage practices. What is, however, striking, is that there seems to be a discrepancy between those we can call insiders and outsiders in terms of opportunities to be included. Marginalized groups (defined as ‘Different groups of people within a given culture, context and history at risk of being subjected to multiple discrimination due to the interplay of different personal characteristics or grounds, such as sex, gender, age, ethnicity, religion or belief, health status, disability, sexual orientation, gender identity, education or income, or living in various geographic localities’ by the European Institute of Gender Equality), who for whatever reason are less or not involved in mainstream economic, political, cultural and social activities, are hardly mentioned as specifically targeted groups. Of all 168 best practices awarded between 2015 and 2020, only two were stated to be explicitly or exclusively directed toward people with disabilities and another two toward (contemporary) refugees. (Ethnic) Minority groups figured in four other projects.

Unlike the Europa Nostra Awards, nine out of the 11 best practices highlighted by the EAA award mention specific target audiences who have been engaged or who benefit from their practices (

Figure 11). The local community was mentioned in 47 per cent of these cases, followed by academics (16%) and students and visitors (each 11%). None of the best practices mentioned the inclusion of people with disabilities, while the target group “minorities” (mentioned once) refers to ethnic minorities.

Many groups experiencing marginalisation or struggles to gain access to resources and full participation (such as the homeless, sick people, the unemployed, addicts, etc.) were not mentioned at all in either award system and remain invisible in these best practices. This is a recurring observation which the authors also made in regard to the inspirational heritage practices they studied in five European countries [

1] and in analyses of World Heritage nomination dossier [

28]. Given the acknowledged potential of heritage projects to make a difference for people in terms of well-being and quality of life, initiators of heritage projects could make a bigger effort to address such groups as well. Moreover, organisations such as Europa Nostra and the EAA could use their influence to further encourage inclusion of the marginalized and invisible groups by supporting and showcasing precisely such initiatives.

4.7. Values and Societal Objectives

For a considerable number of 74 (44%) of the Europa Nostra awards an explicit societal aim was mentioned, with a large variety of aims that could be placed under the ‘social component’ of the Council of Europe’s Cultural Heritage Strategy for the 21st Century [

4]. Among these, accessibility is mentioned most (

Figure 12), although not in relation to specific target groups such as disabled persons (as was discussed above). These figures also show a limited amount of attention to improving diversity and well-being. Half of the aims mentioned refer to the Council’s economic development component. It is striking that re-use of heritage and revitalizing regions are important aims, while tourism seems to have become subordinate. Employment is not mentioned often either, but it may be considered part of sustainable development and capacity building.

In the EAA awards, local engagement and social improvement are valued highly as well (

Figure 13), even though such objectives do not seem to be explicitly visible in the award criteria and organizational aims that are geared towards the knowledge component. Striking is that the value of economic development has been mentioned four times as a decisive component of winning EAA Heritage Prize projects. This seems to contradict the prize’s aim and criterion to “discourage a focus upon

any commercial value” (emphasis added by the authors). Tourism, on the other hand, is only mentioned twice.

When comparing the two award systems, it is interesting to note that the (instrumental) societal values mentioned in the justifications are abundant but diverge quite a lot. The value of accessibility that is recurring in the Europa Nostra Awards is not reflected in the EAA Heritage Prize, while objectives focusing on ethics, diversity and for instance gender equality—all part of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals—are absent from the Europa Nostra justifications.

5. Discussion and Recommendations

The observations resulting from our analysis of awards tell us that the practice of highlighting and celebrating best practices in heritage management needs reflection. Prize giving organisations should be aware of the position they are in, as role models, and that this brings along a moral obligation. They need to give the right example to their members and to the wider profession. As defining and awarding best practices thus relates to leadership, governance and ethics, in the authors’ opinion it also requires accountability. As membership organisations of professionals dealing with the topical subject of heritage, which is part of EU governance strategies, they can be expected to show responsiveness to a diversifying society. They therefore also need to be willing to reflect on potential inequalities and (implicit) biases they perhaps unconsciously and probably unwillingly maintain or even strengthen by showcasing exemplary methods and practices.

The need for accountability pleads for a larger transparency, to start with. It is only by looking at the awarded practices in a holistic manner, over several years, across the whole of the European continent, that patterns and trends may occur. It is therefore important to iterate the limited availability of data on the nomination dossiers the authors had. We were able to only work with the data made available via the public websites, and only on winning dossiers. Acting as moral compasses, awards demand openness regarding both the selection process and the composition of juries.

Justifying diversity and inclusion is equally important in celebrating best practices, as in all other contemporary governance activities. We observed in our sample a strong gender bias, with men receiving many more awards, which begs an explanation and a mitigation strategy. We can think of three possible effects reflected in this, and which need to be addressed. First, it is possible that the juries had to select from an already biased pool of nominations and that the awards only highlight the gender imbalance present in society. While the cultural heritage sector provides employment to a predominant part of women, they are underrepresented in senior management and leadership positions [

24,

25]. Top positions in research institutes are still dominated by men, and may put more male than female practices forward for honourable distinction.

Equally possible is the presence of implicit bias leading to structural gender disparities in awards. What has been called the “Matilda Effect” [

29] is an under-recognition of women’s contribution in science. Van den Brink and Benschop [

30] have scrutinized academic evaluations of Dutch professorial tenure that are alleged to be merit-based and objective, but in reality only uphold inequalities. Through problematising the social construct of ‘academic excellence’ and the ideology of meritocracy, they showed that the gendered selection process disadvantages women, with women being held to a higher standard than men and expected to excel at every level, when this is not anticipated of men [

30]. This gender disparity in awards is also seen in the so-called STEM domain (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) [

31], in performance ratings [

32] and in student research awards [

33]. Moreover, an increased representation of women does not automatically mean the professional field becomes more gender equal. This bias is sustained by both men and women because of internalized assumptions about men being perceived as more competent than women [

34,

35]. Due to such biased expectations, such as men being more competitive, excellent, available, etc., we thus create a barrier to women becoming researchers. The Gender Social Norms Index of 2020 illustrates that 86 per cent of women also show at least one clear bias towards gender equality and women’s empowerment [

36], which corroborates earlier research on gender stereotypes in the workplace [

37]. Thus, the cultural heritage sector where women are well represented does not mean it is free of gender bias. Rather, thinking that gender bias is no longer an issue may actually be a key driver of widening the gender gap, leading to fewer women being promoted to leadership positions because of the belief that gender equality has been achieved [

35].

Lastly, the role of women as

creators of cultural heritage has been undervalued and marginalized. According to UNESCO, women’s culture-making and culture-transmitting activities are often seen as mundane, domestic, every-day duties, less prestigious than man-made architectural or industrial heritage which concerted efforts are made to conserve [

38]. Moreover, these efforts are born from choosing and using heritage values to construct an androcentric narrative of the past that portrays men as powerful and heroic, but excludes indigenous, disabled and non-male humans [

39]. It even renders their contributions invisible, which can be seen in contemporary heritage exhibitions, popular books, school books etc. (e.g., [

40]).

We therefore see the need for award organisations to close the jury gender gap. The advice given is for committees to become aware of gender practices at play, and that these committees should be held accountable for the decision-making process [

30]. However, diversity in decision-making teams alone is not enough to create an inclusive climate. Empirical studies have shown that what is needed too is inclusive leadership [

41]. Inclusive leadership, which sustains a climate in which the norm is to be open to differences and to value these, has a positive impact on inclusiveness in governance [

41]. Such leaders “seek to understand other cultures, challenge the status quo, and be an advocate of equity for all” [

42]. Leaders of organisations awarding excellent practices should therefore be self-reflective regarding their inclusive leadership performance. However, this is not to say that members should wait for boards to change themselves. Here lies a task for members of organisations such as EAA and Europa Nostra as well, as members have the power to vote for representatives that embrace and commit to diversity and equity.

A third and final recommendation relating to our plea for accountability is to frequently revisit the award selection criteria. They need to be assessed, ideally by ethics committees, for clarity, relevance, timeliness and equity, and for the values they promote. This is important for three reasons. First of all because criteria for selecting best practices which are relics from the past may easily reflect the more traditional heritage management paradigms, its intrinsic values and historical approaches and may not necessarily encourage new and instrumental uses of heritage or promote the whole range of values associated with heritage practices. In the awards discussed in this chapter, heritage as a driver of economic development is for instance a value and practice well-acknowledged as a good approach, and it is frequently addressed as a societal aim by heritage practitioners, but in doing so there seems to be a risk of exclusion of marginalized groups or people living in rural or remote regions. Future award nominations and juries could easily be asked to take such inequalities into account by enhancing the criteria. A second example concerns social objectives. These are clearly included in contemporary practices and appreciated by juries as well, but there is still a world to win too. The practice of using heritage to make a difference for individuals in terms of well-being and quality of life, for instance, is hardly visible in the awards yet, at least it is not mentioned explicitly. We believe there is great potential to promote heritage as a resource to attain the United Nations 2030 Agenda and its Sustainable Development Goals [

43], thus, if awards are meant as best practices, illustrating both the sector’s managerial state of affairs and its societal responsibility, criteria encouraging social equity and human rights are key.

Another reason to re-evaluate the criteria relates to the categories of heritage so far included most. Looking at the process of what type of heritage is considered to have value, “assigning significance to heritage is the outcome of choice and has a direct connection with participation in decision-making processes.” [

38]. The gender disparity as discussed above demands for an increased valuing of historic relics traditionally associated with women’s roles, such as the heritage of taking care, food production, textile work, or birthing practices.

A third reason to revisit awards criteria relates to the language used. Vocabulary is powerful in terms of promoting inclusiveness and diversity. Language can reflect implicit bias and—when used unconsciously—continue to promote stereotypes. It can, however, also help avoid bias and support diversity and inclusion. Implicit bias means that we assign qualities like innovation, excellence, leadership, dedication, etc. much easier to men than women. Additionally, a category such as (excellent) research is much more linked with men, as was discussed above. We believe the vocabulary used in awards criteria is therefore part of the problem of a lack of diversity in award winners. Award criteria using a vocabulary that leads to subjective evaluations of ‘outstanding’ achievements and ‘excellent’ contributions and a dedication that is ‘beyond normal’ should therefore be avoided.