Abstract

The value of historical railways and their important role in social, economic, technical, political, and cultural terms has led to their inclusion as industrial heritage attractions. This study aims to evaluate the heritage value of the Oraviţa–Anina linear railway, the first mountain railway in Romania. The assessment of the value of the railway involved both quantitative and qualitative methods. The value was assessed on the basis of a rigorous quantitative evaluation of key attributes of heritage railway, using a system of criteria and indicators. On the other hand, the selected qualitative methodology facilitated the critical interpretation of the perception of the local community as a beneficiary of the railway heritage and as an active stakeholder involved in its reuse. The qualitative evaluation of the heritage railway was also highlighted based on a critical analysis of tourists’ perceptions. The results indicate the usefulness of a mixed methodology for the complex evaluation of the value of a heritage railway and its sustainable capitalization. Railway tourism is a sustainable solution meant to stimulate interest in learning about local history and culture, and can at the same time contribute to the fulfillment of knowledge of the motivations that drive tourist demand.

1. Introduction

In Europe, railway heritage was not initially included in cultural patrimony because it belongs to the industrial field and was perceived as a recent legacy of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries [1] (p. 8). The development of rail transport is closely linked to the Industrial Revolution [2,3,4]. The emergence of steam locomotives marked an important stage of the Industrial Revolution, with rail transport contributing to the development of industrialization worldwide, serving various industries [2]. At the same time, rail transport also contributed to the development of society in the nineteenth century [3], representing a symbol of progress in different countries [5]. Over time, the railways developed significantly and facilitated long-distance freight and passenger transport, spreading from the United Kingdom to other countries [6].

Railway transport has significantly contributed to the development of Romania in different historical stages. The first railways were put into use on the current territory of Romania in the second part of the 19th century, in the provinces of Banat and Transylvania, annexed at that time by the Austrian Empire and, respectively, the Kingdom of Hungary, which later, following the dualist pact, have become Austria-Hungary (1867) [7,8]. The construction of the first railways was linked to serving some areas of the extractive industry (in Banat: coal, in Transylvania: gold, silver, salt, coal), in order to facilitate the transport of exploited resources to the sales markets [9]. In numerous cases, as a result of financial constraints and technical restrictions related to the geographical setting (predominantly mountainous), numerous narrow-gauge lines were also built [9]. The unification of Romanian provinces of Moldova and Walachia in 1859, marked a turning point in the creation of a framework conducive to economic development, due to the implementation of fundamental reforms that contributed to the modernization of the Romanian state (e.g., to improve and expand the transport infrastructure). The first railways were built under concession starting with the second half of the 19th century, one of the most important lines being the one that connected the country’s capital with the Danube port of Giurgiu (1869) [10]. Furthermore, in the same period, in the province of Dobrogea, annexed by the Ottoman Empire, the Cernavodă-Constanţa railway (1870) built by the English company Danube and Black Sea Railway (DBSR) [7,8]. In 1918, the union of the Kingdom of Romania with the regions of Transylvania, Banat, Bessarabia and Bucovina was achieved. This important historical event generated the development of the Romanian Railway Society, which built different railways according to the conception of Romanian engineers [7,8]. During the communist period (1945–1989), significant investments were made in the development of railways to support the rapid industrialization process of the country, to which is added the construction of railways in rural areas. Starting from 1990, after the fall of the communist regime, Romania is among the European countries with a dense railway network, but at the same time, the process of maintaining and modernizing the railway infrastructure is relatively slow due to financial limitations.

The inclusion of railway vestiges in the sphere of cultural heritage initially faced with two obstacles: a lack of recognition of its cultural and technological value, resulting from its perception as an element of infrastructure with ordinary qualities, to which were added legislative obstacles [1]. Awareness of the heritage value of industrial heritage came late, in the context of deindustrialization, which led to underutilization, abandonment, and the deterioration of many industrial heritage sites [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20], including those making up transport infrastructure [12,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Abandoned railway lines are frequently found in areas where mining or heavy industry units are no longer operational [12,29]. The progressive modernization of railway infrastructure was another factor that led to the abandonment of many historical railway lines, some of which are elements of architecture and civil engineering that have great value [21,30,31,32]. Thus, a legislative framework was created for the conservation of industrial monuments by registering them in the category of cultural assets. The important role played by railways in the development of countries and their multiple values (historical, technical, social, economic, political, and cultural) have led to their inclusion as industrial heritage attractions [12,21,24,31,33,34,35,36,37]. The components of railway transport, built at the beginning of the 19th century, unimaginable a generation ago, represented by outstanding railway technical elements (steam locomotives) or functional buildings (signal boxes, maintenance workshops) are considered innovative elements of the period of the Industrial Revolution that have heritage value in a certain environment, a fact that justified their inclusion in the sphere of industrial archeology [4,38].

The railway heritage includes: heritage railways, working railway, tramways, railway museums, railway journeys in historical wagons, tram museums, and tourist railways; buildings or infrastructure related to the protection of railways, technical skills of construction and management of railways (freight stations, locomotive and tram depots, construction and maintenance workshops, etc.), but also intangible labor memory [23,29,31,39,40,41,42].

In recent years, railway heritage has been capitalized on as a tourist resource in many countries [12,31,43], which has ensured a second life for historical railways, vintage trains, and railway buildings [25]. Tourism is seen as a form of railway heritage conservation and at the same time provides a link with history [24,44]. Additionally, the conservation of railway heritage elements has been ensured by including them in technical museums [44,45], representing the conservation of technological artifacts [46] as static exhibits [43,47]. Some authors have developed the idea of “preservationism” related to the conservation of railway heritage elements as a reaction to modernization and even as collective nostalgia related to the industrial past [2,25,43,48,49,50,51]; rapid deindustrialization has generated a deep sense of the loss of technology (steam locomotives) and of the associated social life [44] (p. 152). From the conservation perspective, the need to highlight the links between the railway heritage and the history through the manner of exhibiting and presenting the types of artefacts to the general public has been justified. In this context, special attention is paid to the concept of heritage railways, which refers to the historical railways that have lost their original function and are reused for tourist purposes as a way of preserving them in the form of a dynamic museum [43]. The term of “dynamic museum” refers to the touristic use of the heritage railways as a way of preserving and extending their existence as well as the memory of the railways. Thus, “dynamic museum” highlights the historical, technological and aesthetic values of heritage railways that indicate the opposition to static preservation [43]. The historical or heritage railways differ from the tourist railways, both in terms of purpose and duration of the journey, as well as in the travel experience offered [43]. In the case of heritage railways, which usually operate irregularly and occasionally, the train is the attraction itself due to its physical characteristics (old equipment: steam locomotives, wagons) [51,52]. Thus, the mode of transport becomes the focal point of the tourist trip, to which the landscapes are added as secondary attractions of the destination [52]. Among the most interesting international heritage railways, we can mention: Talyllyn Railway (built in 1886) [47], which is the first historical line included in the tourist circuit in Great Britain [51], Semmering from Austria, the Rhaetian railway between Switzerland and Italy [2,12], the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway in India, the Yunnan–Vietnam Railway between China and Vietnam [34], etc.

The tourist railway operates according to a regular schedule, and the trip has integrated tourist services, to which are added marketing services, which differentiates them from traveling by train as a means of public transport [43]. In this case, regular trains are used (called tourist trains, e.g., in Brazil: Expresso Turístico—Tourist Express, Estrada de Ferro Campos de Jordão—Campos de Jordão Railway) which have the role of providing transport to different tourist destinations. Unlike historical and cultural trains, the main attraction of tourist trains is represented by the landscape [43] (p. 27).

Although there is a strong relationship between tourism and railway heritage, however, the tourist use of the railway has not always been linked to heritage [43]. Heritage railways were exploited for tourism purposes in the context marked by deindustrialization, the modernization of the railway transport (abandonment of steam locomotives and re-equipment with new means of transport: high-speed trains) or even the privatization of the railway transport and the concession of some railway lines (for example, Brazil), factors that generated a reduction in the use of the old trains and steam locomotives [43]. The authors Moraes and Oliveira (2017) [43] believe that this context cannot be associated with the end of the railway era, but on the contrary, the lack of railway services for travelers influences the interest of tourists for certain travel experiences. In this context, the closing of many historical railways and the inclusion of a limited number of them in the tourist circuit, indirectly triggered the tourist experience because there is little offer [43]. The conservation of railway heritage elements has also contributed to their popularization and recognition by the general public through railway tourism [29,34].

The development of railway tourism is also opportune because it represents an ecological and sustainable form of transport [29,53]. The railway is considered an environmentally friendly and efficient form of public transport mostly due to its low emissions and the reliability of its service [23,53]. In this regard, the European Commission launched in 2021 the campaign “The European Year of Rail” to highlight the sustainability, innovation, and safety of rail transport by encouraging its use both by passengers and for freight transport to facilitate the EU’s Green Deal target of becoming climate-neutral by 2050 [54]. The railway verges offer strips natural habitats for a variety of species [55,56,57,58] and/or corridors for biodiversity: green infrastructure along the rail can play an important role in connecting wildlife [56,57,58]. However, linear transportation infrastructures (including railways) can be both a lifeline for ecosystems and a physical barrier between areas of wildlife protection, thus blocking migration corridors pollution [56]; it generate wildlife mortality from collisions with trains, noise and light pollution as well as air pollution [56,58]. However, railways are less harmful than roads to both fauna and flora: the railway corridor is typically narrow [58] and thus occupies less physical space [56]; the railway tracks are slightly elevated, allowing animals to migrate underneath [56]. Special attention was paid to the measures to mitigate the damages that the railways could generate (fauna crossings made in the form of above-ground and underground passages that can be installed retroactively [56], preventing the passage of animals (for example, by enclosure) measure that can be applied for collision hotspots [58].

In the field of heritage protection, historical railways are related to the concept of “heritage corridor” [59] which implies a similar meaning with linear heritage such as “cultural route“ [59]. “Culture route“ is defined as a linear landscape with a collection of cultural resources along which the function of communication is one of the most important parts to reflect diverse types of culture and social development in the past [59]. ICOMOS representatives from the International Committee of Cultural Itineraries (ICCI) believe that the innovation introduced to this concept reveals the heritage content of a specific phenomenon of mobility and human exchanges, facilitated through the route. Beyond its character as a mode of communication or transport, the existence and significance of the cultural route can be explained by its use for a specific purpose and by the fact that it has generated heritage values and cultural properties associated with it that reflect mutual influences between different cultural groups as result of its own specific dynamics over long historical periods [60].

Some authors consider that rail transport could be the most appropriate way to make sustainable mobility policies at an international level [53]. As a result, the use of rail transport for both citizens and tourists is encouraged in different countries [25]. If we refer to the particular situation of the use of historic steam engines and vintage trains on heritage railways, whose operation involves the burning of coal, this is an activity that generates pollution and is in contradiction with the tendency to limit or even completely prevent the burning of fossil fuels. The regulations regarding the orientation towards an economy without carbon emissions adopted in different countries, threaten the activity of the operation of heritage railways [55]. Debates on this topic raise the issue of whether it is sufficient to invoke the rarity and cultural importance of steam locomotives used on heritage railways to justify the fact that this activity generates pollution that can be compensated by ecological regulations (e.g., planting trees) [55]. Carbon emissions are a major concern, including for representatives of technical museums, industrial heritage organizations and heritage railways, and the solution requires the identification of some forms of sustainable future use of steam locomotives. Furthermore, identifying the best solutions is a challenge and requires collaboration between experts from technical museums and industrial collections, from fields related to industrial heritage (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) and environmental education [55]. These debates are useful because they justify the continuation of railway tourism in a sustainable way by foreshadowing the future planning of how steam locomotives will operate. In this context, the ethics of modifying historic engines to use new low-emission technologies has been brought into discussion. Historic engines are often adapted to new or modified fuels over the course of their working lives [55] to improve their performance [61]. However, this measure does not comply with the conservation criteria applicable to collections hosted by accredited British museums, and its implementation will be difficult to accept in the next 5–10 years [55]. An alternative solution would be to build engines that use new technologies to demonstrate mechanical principles. This alternative solution is necessary, especially in the event that the burning of fossil fuels would be permanently prohibited [55]. From the point of view of authenticity, adaptations are interesting from the perspective of explaining changes in processes or work models [61]. At the same time, the negotiation of new climate regulations at the local and national level are considered compensation measures for the carbon emissions generated by the historic engines that would allow the current ecological legislation to coexist with the historic engines. These compensatory measures are justified by the cultural importance of the steam locomotives which provide a directly lived experience and which allow at the same time to explain to visitors the history and reality of industrial work, thus contributing to the public’s appreciation of the past which, in the absence of their operation them, it would be irrelevant [55].

With regard to the current debates regarding the technical interventions on the historic engines with the aim of extending their functionality, it is also necessary to approach the ways in which the historical importance of the steam locomotives can be reconciled with the need to operate them for tourist purposes [47]. Extending their functionality involves technical revisions necessary to ensure the highest possible standards of operational safety. At the same time, revisions must be compatible with the exigencies of conservation practices [47] that limit changes to artifacts to prevent imminent heritage losses [62]: e.g., minimal interventions on its components and appearance [47]. For example, in the UK, the operation of steam locomotives on heritage railways is based on compliance with a conservation management plan which includes a series of overhaul guidelines (e.g., replacing existing components where absolutely necessary, using replication of damaged components by reusing the original components taken from other locomotives or, when the second situation is not possible, the replacement components must be of the same material) [47]. There is also the situation when some locomotives used on heritage railways have been rebuilt or replicated following the remanufacture of almost exact copies of an original [47], a situation that affects the historical importance and authenticity of vintage trains [47,61]. On the other hand, it was necessary to make some compromises in order to comply with the safety and operation standards of some steam locomotives that have registered a long industrial use followed by a re-use for tourist purposes. Conservation is not without contradictions [62], especially since this also involves interpretation [47]. Compromises are acceptable to the extent that a steam locomotive is capable of operating to be kept in service. In this context, a development of the railway market is foreshadowed, emphasizing the value of heritage railways as well as the quality of the travel experience [25,63].

Given the importance and complexity of railway heritage, researchers’ interest in its optimal evaluation, conservation, and monetization through railway tourism is justified. As a result, this study aims to assess the heritage value of the historical mountain railway Oraviţa–Anina, to serve as a useful tool in its sustainable use as a linear cultural site by local, regional, and national decision makers. The multiple meanings associated with this historical railway necessitated the use of mixed methodology (quantitative and qualitative), with the results being processed with the support of ArcGIS software (ESRI, Redlands, CA, USA), allowing for its promotion as a linear heritage attraction.

The objectives of this study are: (1) to evaluate, in a complex manner, the historical railway Oravița—Anina, both from the perspective of its values as a railway heritage resource, applying an evaluation system, and from the perspective of the perception of the local population and of tourists to justify its reuse as a heritage tourist attraction; (2) to identify the main stakeholders and their degree of involvement in the tourist reuse of the heritage railway Oraviţa-Anina. In order to fulfill the objectives of the study, the authors used a quantitative evaluation based on a system of six key attributes analyzed in close correlation with the criteria and indicators adapted to the specific characteristics of the railway heritage, and a qualitative evaluation focused on the critical interpretation of the local community’s perception as a heritage beneficiary and stakeholder that can be involved in its reuse. The qualitative methodology facilitated understanding the voice of the local community in its attempt to sustainably reuse heritage railway. This important aspect draws attention to the need for community involvement also in the future stages of the research regarding the vision of local development correlated with the increase in the benefits generated by railway tourism. At the same time, the qualitative methodology validated the attractiveness of the railway heritage to tourists through a critical analysis of tourists’ behavior. In order to better establish and clarify the purpose and objectives of the study, the main research questions were formulated: What are the heritage values of the historical Oraviţa-Anina railway?; How can the values of the heritage railway be evaluated in a complex manner? What is the perception of the local population towards the heritage railway? Is the local population an active stakeholder in the action of reusing the railway as a heritage attraction? What is the degree of appreciation of the tourists regarding the heritage railway Oraviţa-Anina?

2. Literature Background

Railway heritage is among the most valuable elements of industrial patrimony [4,12,30,34,59], due to several values: the technological one (the pioneering elements from the period of the Industrial Revolution, which can be unique); the fact that railways had economic significance, as well as social and political importance. This justified the inclusion of some railways (e.g., Semmering in Austria) on the World Heritage List from the mid-1990s [25,50,64]. The usual criteria for the classification of classical cultural assets have been adapted by UNESCO representatives to make them applicable to railways [2,64]: a creative work indicative of genius; the influence of, and on, innovative technology; an outstanding or typical example; and illustrative of economic or social developments. Industrial heritage includes remnants of an industrial civilization [3,4,12,14,17] whose management as cultural attractions based on multiple uses (recreational, educational) can generate significant benefits today, especially in the context marked by the reduction of industrial activities and the development of the services [12,13,24]. Industrial heritage attractions can be further sub-divided into specific types of attractions, of which railway heritage forms one category [12,24,31]: “transport attractions” [65]. At the same time, the railway heritage has an aesthetic and educational value, these being arguments for its touristic exploitation [51].

The heritage generated by railways is seen as a high point in railway tourism [52], and generate a particular experience [12,38,43,52]. Heritage railway routes can be traversed with original locomotives (steam locomotives) and wagons for aesthetic and technological reasons, proving that, despite their age, they can still be functional today [44] which explains the emotional appeal of steam locomotives [38]. Traveling on heritage trains contributes to the discovery by tourists of some elements of railway heritage such as depots that were previously forbidden places but now can be visited respecting strict health and safety regulations [44]. Erving Goffman (quoted in Hallsall, 2001) [44] (p. 153) considers depots and railway workshops as representing the back regions which attract interest of tourists because they are associated with intimacy of relations and authenticity of experiences. The inclusion of heritage railways in the tourist circuit by operators increases the number of tourists, especially of stereotypic eccentric railway enthusiasts; thus, heritage railways can be classified as objects of the collective tourist gaze [44] (p. 153).

Heritage trains are also considered objects of romantic interest, giving passengers the opportunity to relive an old travel experience or others the opportunity to have an experience with a historic train for the first time [44]. The presence of artefacts and their observation while they function, represent for visitors an opportunity to live an experience of the past directly [51]. The railway heritage is part of the memory of those who initially used the old trains, which they associate with a historical period [52], namely the Industrial Revolution. In the case of vintage trains, the heritage involved creates a sense of belonging to the subject, especially for those who had a direct relationship with the railways, either through their use or because they had a certain function within railway transport [52].

Some heritage railways run only part of the original route and are not connected to a railway network, in most cases running only occasionally. As a rule, historical railways that have a short route length are open to the public during weekends and public holidays. Historical railways with longer lengths are operational throughout the week [51]. Many heritage railways have a narrow gauge [31,35,66,67], but they can also have a broad gauge (1435 mm). Some heritage trains run on the national network, and others may have a route in several countries [23,29,31,39,40].

Attractions associated with heritage railway can also be part of other heritage assets: as a means of ensuring the mobility and access of visitors within a destination and tourism attractions [12,31,44], or by facilitating travel to tourist attractions in ways that make them part of the tourist experience [12,31,44,52]. Thus, tourist monetization on the heritage railway attractions can also contribute to the capitalization of other elements of industrial or cultural patrimony [12,31]. Additionally, the geographical location greatly influences the successful operation of tourist railways and in particular of heritage railways. Development perspectives present the railways located in attractive tourist regions and in the vicinity of large cities [12,66] as a result of the fact that the presence of both a tourist railway and heritage railways is not enough to transform a certain location into a tourist destination [43].

In this context, railway tourism involves the analysis of several aspects as a result of its complexity: the problem of tensions between the value of use and the symbolic value [43]: the way of using historical railways should be evaluated from an ethical perspective, especially when attention is drawn to the aesthetics of the heritage elements and less to the historical value and narratives that accompany them [51]; tensions between the need to generate income and the desire to manage a credible heritage railway [51], respectively the issue of financing the conservation of heritage attractions and their exploitation and maintenance [47,51,66]. These tensions are based on the issue of the current debate on the sustainability of railway tourism, especially the capitalization of the heritage railways as a historical representation, as an educational tool, on the one hand, and the heritage railway reused as a theme park, which corresponds rather to ensuring the current needs of recreation and entertainment, on the other [51].

The railways are also analyzed in relation to the landscapes they cross; the railway is considered a tool used to perceive landscapes, and a creator and reformer of the landscape [23] (p. 3), thus presenting aesthetic value and increasing the attractiveness of the landscape it crosses [12]. In addition, due to the way they are structured, railways serve as a useful platform for appreciating and contemplating cultural landscapes [5,23,25,53,68], especially for tourists who want to discover the aesthetic and cultural value of the area located in the vicinity of the important tourist centers [53]. As with other forms of tourism, there is a close link between rail tourism and environmental resources [12].

The attractiveness of the railways is also conferred by the aesthetics of the landscape. During the Industrial Revolution, the train, perceived as a large industrial machine, was considered to be in contrast with the aesthetic natural landscape. Over time, due to the development of railway tourism, its negative image changed, contributing to the increase to the attractiveness of train travel [23]. Moreover, the railway elements facilitate the journey along a recreational route [5,25,29,31,69]. A slower rail trip allows tourists to observe more details of the landscape: the local culture, the dynamics, and the social values of the community [70,71]; buildings with architectural value [70,71]; thus, the landscape becomes as a way of interpreting the place [71]. The wagon frames the landscape and surrounds the traveler [71]. Although this situation imposes a distance, it also allows a more careful understanding of the landscapes [71] and leads to an abstraction based on the nature of the journey: the train, unlike other means of transport, is considered one of the best aids to thinking: the views do not have the potential monotony of those from a ship or an airplane; at the same time, after a train journey passengers can feel that they were in contact with emotions and ideas important to them [71]. Traveling by train is described as a proto-cinematic experience, a fact highlighted by its relatively constant speed (unlike traveling on foot or by car) and by offering a panorama over the landscape [71]. The choice of a particular type of train (high speed or slow) is determined by the traveler’s preference to linger and understand a place and the wider landscape in which they are. For example, regional architectural variations will not be easily visible in the case of a high-speed train journey, although the diversity of landscape types can be identified [71]. The analysis of the relationship between the landscape and the railway was materialized creatively through the concept of a “scenic railway,” defined as a railway used for leisure, entertainment, sightseeing, and heritage experiences [23] (p. 4). The railway is the core bordered by related functional, cultural and historical heritage assets [59]. Thus, considering the particular assets of railway heritage and the cultural resources located along the way, as forming a whole, it is considered a heritage landscape distributed in a linear space [59] (p. 1). The historical value of the railway is conferred both by technical, military and cultural communication, as well as by the “route“ [59].

Some authors consider that cultural landscapes and railways also have educational value [25,43,51,53] because it determines how people learn about the landscape through a simple and sometimes distant or fleeting observation depending on the type of train selected [71]. The railway also allows landscapes inaccessible to other modes of transport to be admired largely due to the geometric limitations of its route [53,71]. Thus, traveling by train is an option of the traveler who prefers a scenic experience of great aesthetic value [53].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

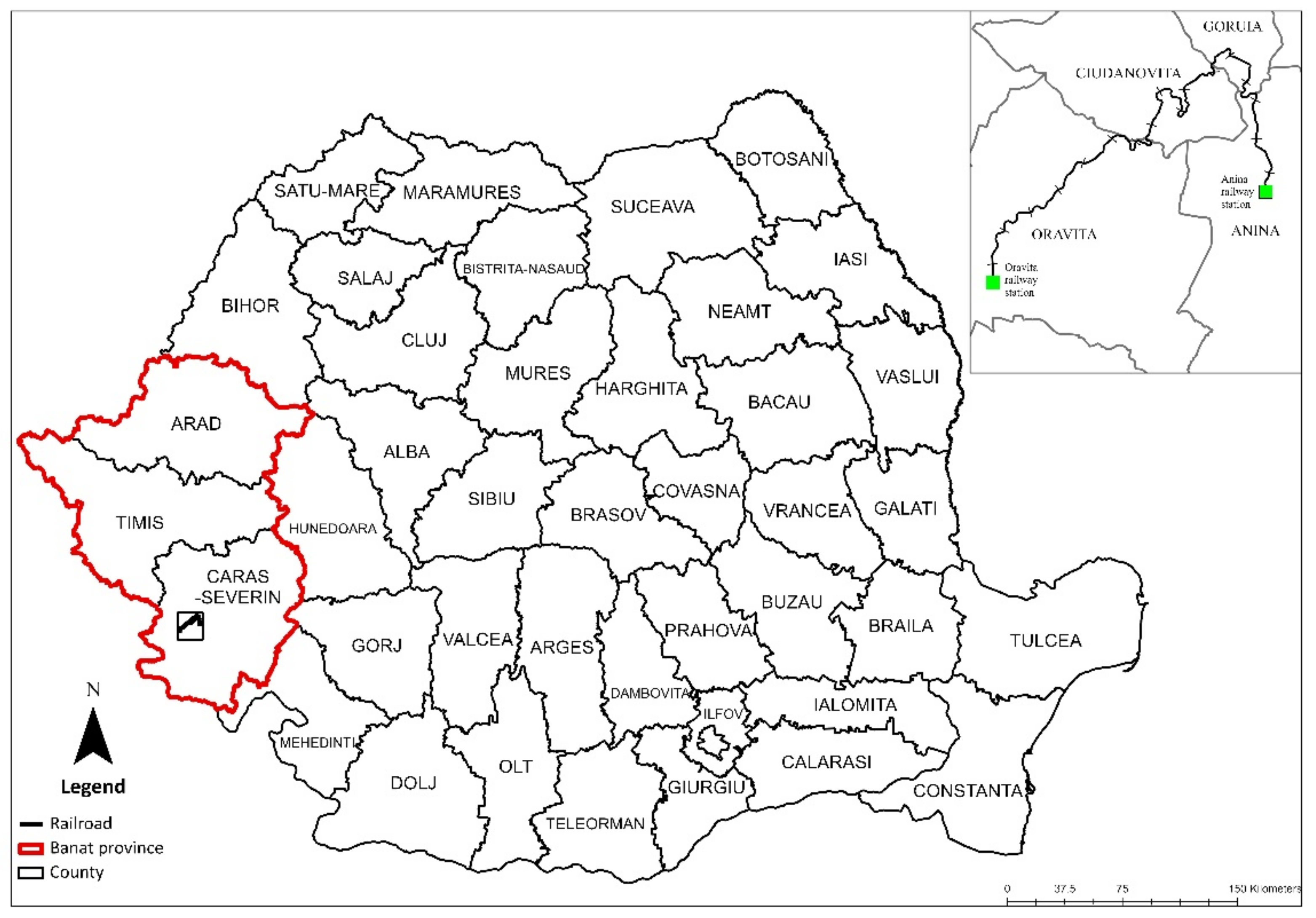

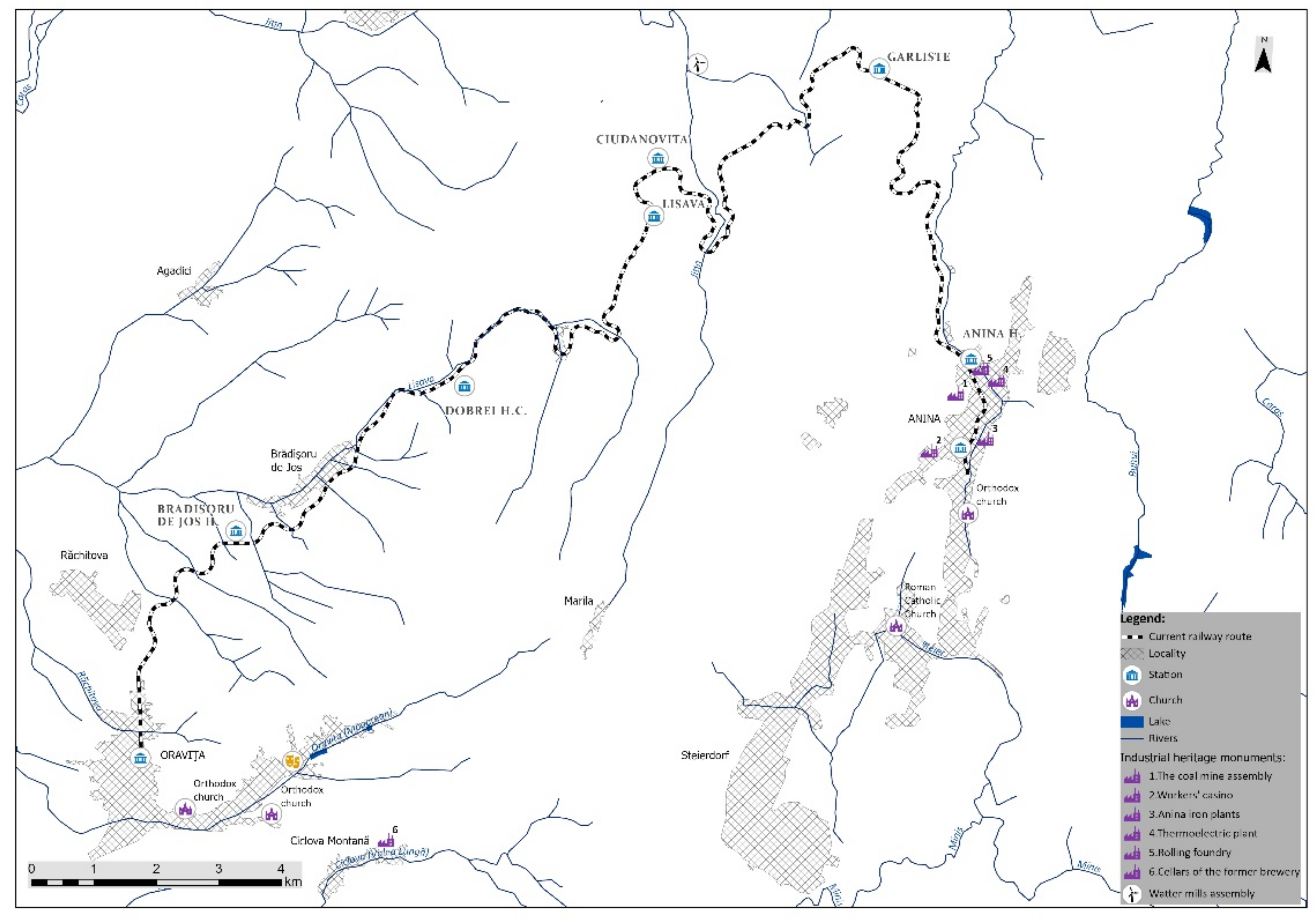

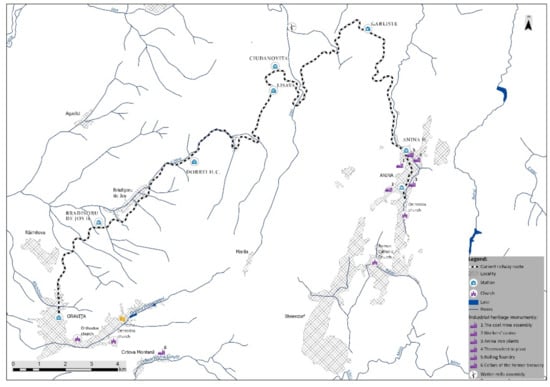

The Oraviţa–Anina line is one of the most spectacular and difficult railways in Romania due to the fact that its construction required works of engineering art made in a mountainous environment in the absence of modern technologies. The historical railway is located in the southwestern part of Romania, in Banat province (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location of Oraviţa–Anina railway. Source: processed by the authors.

Oraviţa–Anina was the first and most important mountain railway line on the current Romanian territory [7,8]. It has served freight transport since 1863 and has been open to passenger traffic since 1869 [7,72]. The construction of the railway line was considered a strategic investment by the Austrian Empire in order to transport the coal mined in the southern part of the Banat province, to the Danube and from here by ship to Vienna. The coal mines in Banat are the oldest in Romania and were linked to the interests of the Austrian Empire and later of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which annexed this province from the early 18th century to the first half of the 20th century [73,74]. Therefore, the railway was also called the “coal line” [7,74].

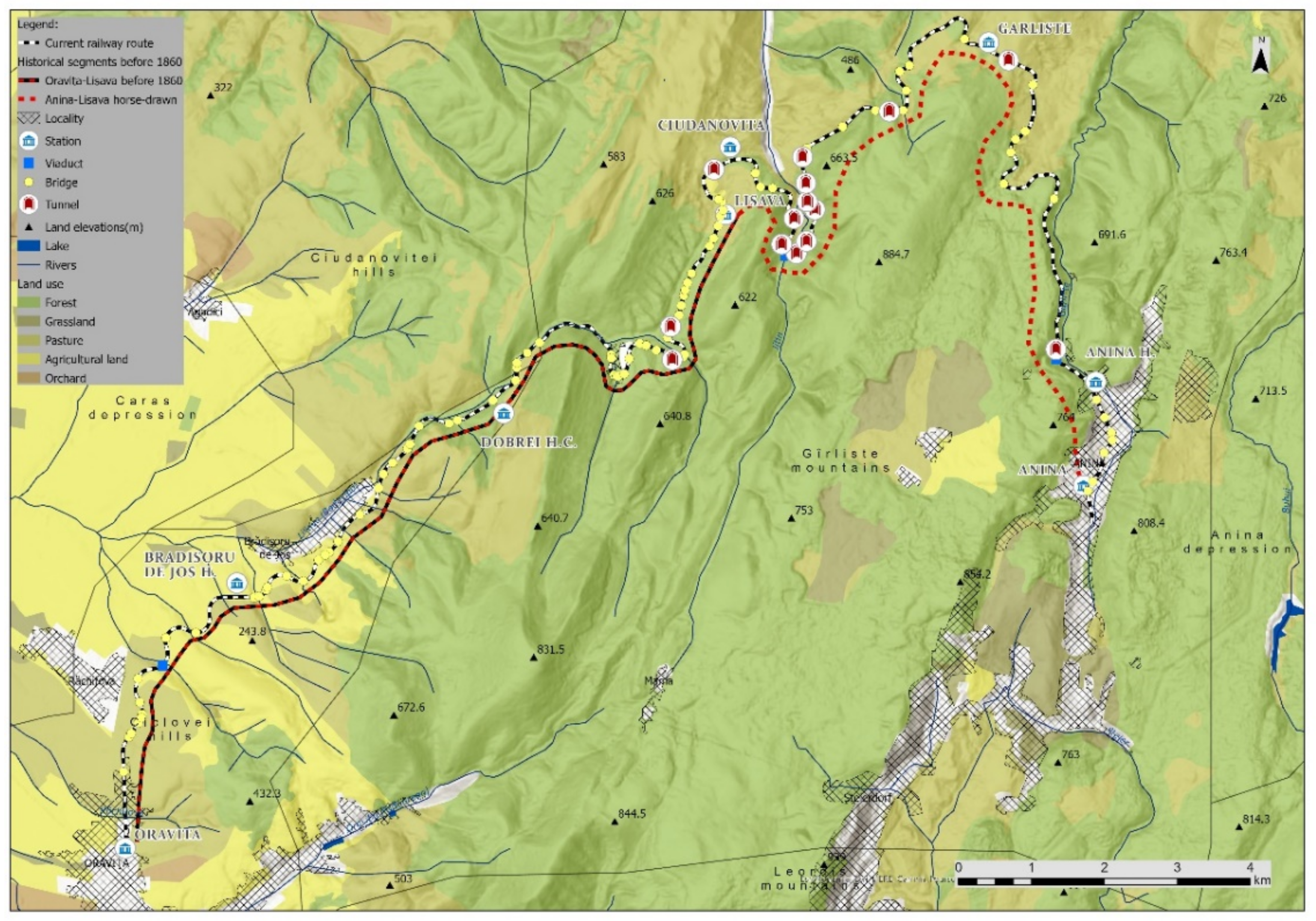

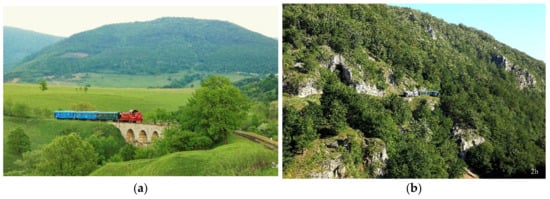

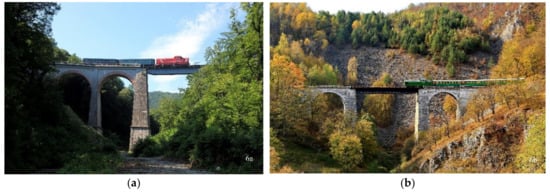

The spectacular route, which is 33.4 km long [7,8], crosses of areas that are distinguished both by the increase in altitude and by the various forms of relief: from the town of Oraviţa, located in a depression area characterized by low altitudes (220 m), the line climbs to the town of Anina (559 m altitude), located in a mountainous area. Thus, the route has a level difference of 339 m. The Oraviţa–Anina railway is a linear site that includes a succession of natural and cultural landscapes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The succession of mountain and hilly landscapes along the railway route: (a) viaduct between Brădişorul de Jos halt and town of Oraviţa; (b) railway route in mountain area before the Schlucht viaduct (near the town of Anina). Source: Dorobanţu Mircea.

Along the route, the views are picturesque; in some segments, the railway passes through limestone outcrops, which impose very narrow widths on the route. Due to its antiquity, the railway was included in the Heritage List [75], being classified as an industrial site of national importance. The Oraviţa–Anina line has a normal gauge.

3.2. Methodology

The methodology of the study involved a combination of various methods based on which the tourist attractiveness of the historical railway Oraviţa–Anina was evaluated. We consulted various studies focused on quantitative assessment of railway heritage elaborated by organizations in the field of railway transport, scientific articles in the technical field, cultural heritage, architecture, geography, etc. [12,34,61,76,77].

Taking into account the patrimonial value of the analyzed railway site, the qualitative method was applied because it allows for an in-depth interpretation of its significance for the local community and the degree of appreciation of the tourist experience.

The authors used Geographic Information System (GIS) to analyze the data in depth and adequately represent the diversity of the component elements of the historical railway. GIS has also been applied in studies dedicated to linear historical sites in the category of railway heritage [50], historical roads [78,79], or nature tourism routes [80].

3.2.1. Selection of Criteria and Indicators for Evaluating the Values and Tourist Attractiveness of the Heritage Railway

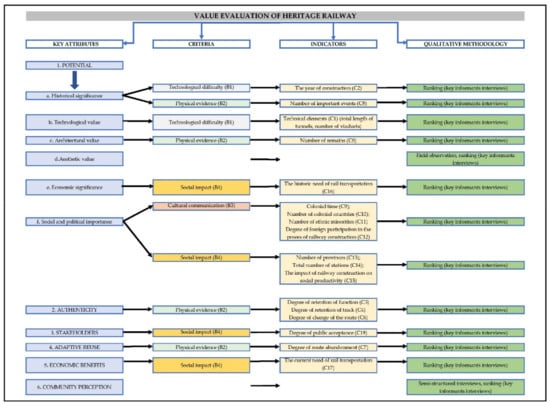

The authors used a framework for assessing the heritage value of the railway site that includes six key attributes adapted to the railway heritage, proposed by Xie (2006) [77] and also called critical success factors [12], as well as a number of associated indicators proposed by Jiang, Shao, and Baas (2009) [59]. The six key attributes are:

- The potential that justifies the selection of some elements of railway heritage as cultural tourist attractions at the same time offers an interaction between visitors and local heritage.

- Authenticity.

- Stakeholders.

- Adaptive reuse.

- Economic benefits correlated with economic sustainability.

- Community perception and social sustainability.

- The tourist potential of the heritage railways consists ofof its multiple types of value [12,23]. A set of criteria for assessing the potential of heritage railways has been established [12,23,59,77,78]:

(a). Historical significance correlated with historical characters and events

(b). Technological value, uniqueness, and representativeness;;

(c). Architectural value;

(d). Aesthetic value and the relationship between the railway site and the landscape;

(e). Economic significance;

(f). Social and political importance.

- (a)

- Historical significance. The railway has a historical past and a narrative behind it, related to the context of its formation and functioning in the era of the Industrial Revolution. Additionally, its historical value is linked with historical people, events, and activities that influence its originality and authenticity [34]. Each railway attraction is special, being defined by its own location and history [12,34].

- (b)

- Technological value is a basic criterion for assessing valuable railway heritage elements, which is also the attribute that individualizes them among other categories of industrial heritage [59]. Due to railway heritage belonging to industrial patrimony, numerous studies concluded that, unlike classical cultural assets, industrial ones present significant technological value. The construction of historical railways involved several technical difficulties that had to be solved by engineers [59], which gives them uniqueness and representativeness: steep slopes, height, number of curves and loops, slope arrangement, safety measures, construction of technical engineering elements (bridges, tunnels, and viaducts, as well as types of locomotive); for example, specific technical solutions were needed for mountain railways: loop lines and spiral loops, specially designed engines, etc. [34].

- (c)

- The architectural features reflect both local cultural and historical elements, as well the characteristics of the geographical settings. The stations are considered the main elements for the study of architectural aesthetics from previous periods, being one of the oldest industrial heritage assets observed by the public [50].

- (d)

- The railways have aesthetic qualities enhancing the landscape through which they pass [12,53]. The landscape is seen as being integrated into the railway heritage. The quality of the landscape becomes significant for railway heritage and tourism [23,81]. An area with high landscape value contributes to shaping a significant tourism value. For instance, in the case of the railways included in the UNESCO World Heritage List, the railway is understood as a force that generated the transformation of the land and the railway together, as a landscape, representing an attraction for tourists [23]. In addition, the historical railways that cross picturesque landscapes are identified as resistant infrastructure [23] associated with technological value, especially in mountainous areas where the arrangement of the railways has been difficult. Additionally, heritage railways are associated with historical events and public memories of their construction, and facilitated the transport of passengers over long distances and in hard-to-reach areas. Thus, some historical railways are reconstructed as typical cultural routes included in the category of linear historical sites to ensure the connection of tourist activities and preserve the integrity of the heritage in a landscape [23,50].

- (e)

- Economic value. The railway has played the role of transport in history [3,5,34], either as a means of transport for mining industry, urban tram, or forest railway, providing goods and services, generating economic benefits for development of the industry [34]. As previously highlighted, the cumulative action of some economic factors, such as deindustrialization, modernization or privatization of railway transport, determined the closure of many historical railways. Several heritage railway were included in tourist circuits which implies economic benefits: the economic impact generated by the direct revenues obtained from visitors, direct and indirect jobs; investments regarding either restoring and adaptive reuse of original buildings (for cultural or tourist purposes: accommodation units, railway museums) [12,24,32,33,34,66,82,83,84].

- (f)

- Social or political importance. The social and implicit cultural meanings of a heritage railway are also reflected in the communications along the railway routes, such as its role in connecting ethnic minorities [34,59], the public’ attitude towards the railway in the current period, the spread of technologies between different countries, and foreign participation in the railway construction process [34] (p. 2).

- 2.

- Stakeholders: monetization of railway heritage is correlated with the diversity of the stakeholders [12,25,34,77]: active members of core organizations, community and potential tourists, planners, and local businesses.

- 3.

- Authenticity is a basic feature of cultural resources [85,86,87,88,89,90,91] and implicitly of industrial ones [12,25,77,82,92]. Authenticity is a main factor in shaping the vitality of industrial heritage attractions being associated with the concept of genius loci—the spirit of a place [77]. The concept of authenticity has a particular relevance for industrial heritage objectives [92], which is linked to the degree of preservation of installations and equipment (authentic object may be considered as one made from the original components or one whose components correspond to the original model design) [61]. So, authenticity is related to the origin of the objectives, and to the use of authentic objects, in this case the use of historical trains. Authenticity is also related to the way of restoring the elements of heritage railways [25] in order to be reused for cultural or tourist purposes. Movement is an essential part of industrial heritage elements, especially machines and engines. The functioning of industrial heritage objects is part of their essence, as is the conception of the original design. However, the operational use causes wear, which determines over time the repair or replacement of some components, which is why some conservators opt for their inclusion in museums (as static exhibits), thus their authenticity being threatened [61]. This approach is justified if the technical object is unique and has considerable historical importance. The manner of care and display of the technical objects will depend on the recommendations of experts focused on ethical and practical aspects [61].

- 4.

- Adaptive reuse: in the case of railway heritage sites, the reuse of old locomotives, wagons, and traditional lines involves technological limitations, especially if the railway requires certain types of trains with certain technical characteristics [25,82]. The cultural reuse of railway sites is motivated by the possibility of making industrial sites known to visitors as elements of the past. At the same time, for most elements of railway heritage where the main feature of the attraction is the reuse of historical locomotives, wagons, and traditional lines to preserve their use as a means of transport [12,44], they require investments in functional equipment in the form of leisure-oriented transport [31,82], including high maintenance costs [23,82]. Often, the adaptive reuse can compensate for the losses associated with deindustrialization [12,25,46,77], which also implies its importance in the economic sustainability of the monetization of the railway, there being a mutual influence of this criterion with the economic one.

- 5.

- The economic benefits are quantified by the economic impact generated outside of the direct income obtained from visitors: indirect jobs; investments in cultural and implicitly tourism monetization [12,33,82,93]. The economic sustainability of the railway heritage elements is also highlighted by the process of reusing abandoned railway infrastructure, which is related to the circular economy theory that prevents the demolition of old railway buildings and inside seeks to give them a new use in order to make improvements in the environmental, economic, and social dimensions of sustainability: efficiency of materials, cost reduction, and conservation of intrinsic values [82], adaption of heritage industrial buildings to improve energy efficiency: savings in embodied energy by maintenance of traditional buildings using locally sourced materials (buildings based traditionally on their thermal mass for heat, cooling, natural light and ventilation), operational savings (by insulation or renewable energy) [94]. Some authors draw attention to the financial sustainability of tourist railways that must be analyzed, taking into account several factors that may affect the budget such as the seasonality of tourism and the ratio between the resources required for the operation of tourist railways and the number of travelers [12,25].

- 6.

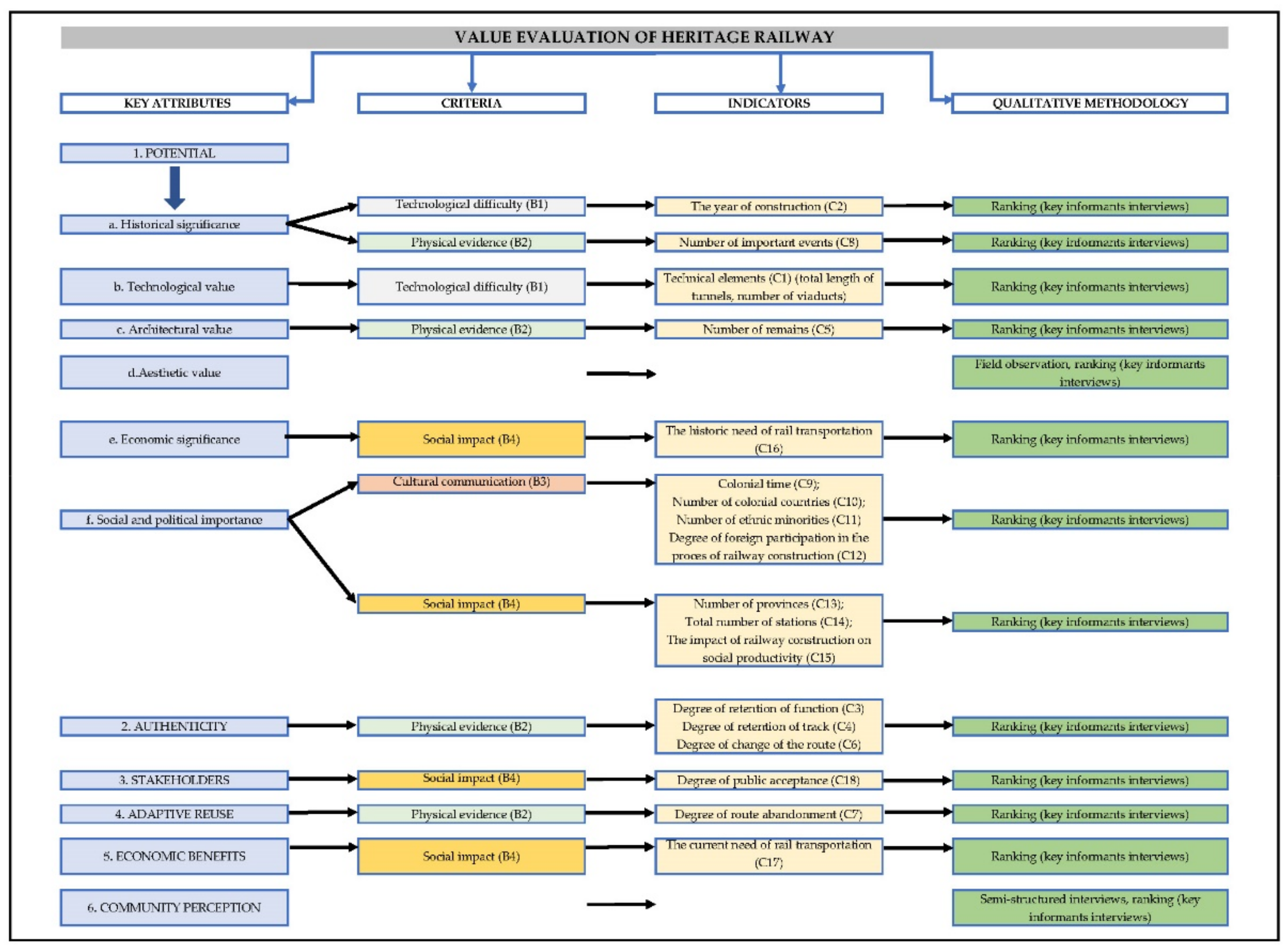

- Community perception and social sustainability. The attitude of the community in relation to the local cultural heritage is very important because it can influence the degree of its optimal capitalization. Various studies have pointed out that the local population shows a strong sense of attachment and identity long after industrial units or railways have been closed [12,73,95,96,97]. Often, the population also has feelings of regret and nostalgia that they associate with the industrial past, related to the disappearance of lucrative and social activities as a result of the decline generated by the closure of industry or railways, as well as the state of precarious conservation of the railway heritage elements (e.g., steam locomotives) [25,44,73]. Thus, the perception of the local community regarding the railway heritage can be analyzed through the prism of social sustainability, with the feeling of attachment correlated with the desire to preserve and capitalize on it [25,66]. To define the value characteristics of the historical Oraviţa–Anina railway, a synthetic assessment of the six key attributes was developed using four categories of criteria and 18 indicators. The criteria and indicators are adapted to the specific characteristics of railway heritage, as proposed by Jiang, Shao, Baas (2019) [59] (p. 5): Technical Difficulty (B1), Physical Evidence (B2), Cultural Communication (B3), and Social Impact (B4). The correlation of the six key attributes with the criteria and related indicators was synthetically represented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Methodological diagram of the way of evaluating the values of the heritage railway. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 3. Methodological diagram of the way of evaluating the values of the heritage railway. Source: own elaboration.

The criterion of Technical Difficulty (B1) consists of 9 important elements with technical value (C1) for defining the heritage railway and the era in which it was built: length of the railway, number of tunnels, total length of tunnels, number of viaducts, total length of viaducts, maximum height difference, slope, gauge, minimum radius of curve. Another important indicator is the year of construction of the railway (C2) whose interpretation from a technical point of view reflects the fact that the older a railway is, the higher its level of technical difficulty [59].

The Physical Evidence Criterion (B2) was applied to evaluate the authenticity and integrity of the analyzed heritage railway: degree of retention of function (C3): it refers to the evaluation of the degree of functionality (partial or total, including the original locomotive); degree of retention of the track (C4): the degree of preservation of the originality of the railway (partial or total); number of remains (C5): richness of heritage; degree of route modification (C6): retains the original line and historic additions to the line; degree of route abandonment (C7): it refers to the state of the route: intact or partial abandoned; number of important events (C8): historical importance [59] (p. 5).

The criterion of Cultural Communication (B3) includes indicators related to the characteristics of cultural changes along the historical railway: colonial time (C9), number of colonial countries (C10): types of foreign culture, number of ethnic minorities (C11): types of minority culture, degree of foreign participation in railway construction (C12): foreign methods of construction and design of the engineering project [59] (p. 5).

The Social Impact criterion (B4) includes indicators selected on the basis of historical and current social development and the demand for the railway [61]: number of provinces (C13): spatial dimension of social impact; total number of stations (C14): the influence on the population that lived nearby; the impact of railway construction on social productivity (C15): the significant impact generated by the railway on social and economic development that marked the transition from a rural agricultural society to an urban industrial society; the historic need of railway transportation (C16): the historic functional importance of the railway; the current need of railway transportation (C17): it refers to the functional importance of the railway at present; degree of public acceptance (C18): the public attitude on railway heritage including history, heritage, and conservation in the current period [61] (Figure 3). Regarding the value evaluation of the Oraviţa–Anina historical railway, out of all the objective indicators, eleven (C1, C2, C9, C17 were analyzed by consulting various bibliographic sources (some of a technical character, developed by specialists in the field of railways, tourist monographs, etc.). The analysis of indicators C3 to C8 resulted from the field research. The last indicator (C18) correlated with the third key attribute (stakeholders) was derived from the interpretation of the results obtained both from the field research and the application of semistructured interviews with members of the local population, including railway employees. For the sixth attribute (Community perception), qualitative methodology was used, based on the application and interpretation of semi-structured interviews (Figure 3).

In order to prioritize and parameterize the quantitative evaluation of the values of the heritage railway Oraviţa-Anina, the authors applied a qualitative method of ranking the key attributes, using as a model the trial application [57]. This method proposed by Baker [57] assumed the evaluation of the potential value of three railway corridors in the province of Nova Scotia, Canada, as recreation routes, using specific criteria (e.g., user satisfaction, non-use values, etc.). Since the present study is focused on the analysis of the heritage values of a historical railway, the authors adapted the method using the key attributes, criteria and evaluation indicators specific to the heritage railways (Figure 3). The second stage of the method involves a ranking of the values. It was necessary to adapt the way of ranking the values used in the trial application. In the case of the evaluation of railway corridors as recreational routes, the method of quantifying the attributes of the route from the perspective of user satisfaction is specified in previous similar studies (measuring magnitude of change in user satisfaction starting from certain values calculated for ideal recreation routes) [57]. In the case of the studies focused on the evaluation of the values of historical railways, the authors identified only one paper [59] in which the values are compared according to their degree of importance, through the relationships between criteria and indicators, using a separate statistical normalization method of data to establish positive and negative correlations. As a result of the fact that the authors do not have advanced knowledge of statistics, the ranking of the attributes of the Oraviţa-Anina railway was achieved by giving scores on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 means a low degree of importance and 5 a very high degree.

According to the methods applied by Baker [57] and Jiang et al. [59], the ranking must be done by different experts called key informants [57] to increase the degree of objectivity of the evaluation [57,59]. Thus, 6 experts were selected: three specialists in the field of railway transport within the Romanian Railways (the first and second experts worked in the Passenger Traffic and Railway Traction Services in Bucharest; the third is the head of the Oraviţa station) and 2 architects and an urban planner who have expertise in the evaluation of elements of industrial and railway heritage respectively.. The first architect is affiliated to the Polytechnic University of Timişoara, and the other two to the “Ion Mincu” University of Architecture and Urbanism—Bucharest. The discussions with experts, focused on the evaluation and ranking of the patrimonial values of the analyzed railway, were carried out in the form of interviews. According to the trial application method, the discussions with experts also aimed at evaluating the criteria established in this study in terms of their suitability and usefulness, leading to suggestions regarding the improvement of the method. Furthermore, this method involves a comparison of the railway evaluation criteria proposed by researchers with those used by experts [57]. The results of this comparison are useful in indicating whether the initial values proposed by the researchers are adequate measures to evaluate the potential of the railway route and whether important criteria for measuring it have been overlooked. The interviews took place either physically with experts from Bucharest or by telephone with experts from other cities, as it was difficult for the interviewer to travel long distances. The interviews were conducted in September 2022. The duration of the interviews was between 30 and 40 min.

3.2.2. Collection of Data

To collect data related to the historical and economic context that generated the need to construct the Oraviţa–Anina railway, we consulted books, technical reports, and monographs. We also gathered technical information related to the construction of the railway. The documentation also involved a review of specialist literature.

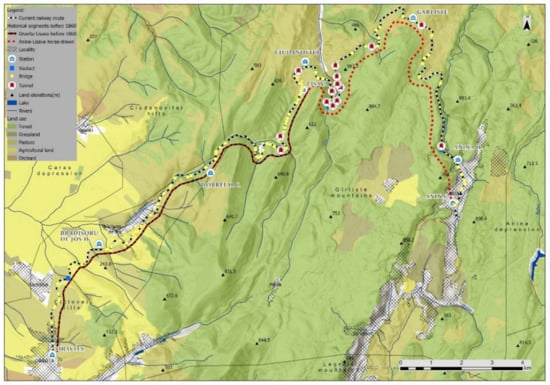

The data sources used to represent the railway site included photograms, old topographic maps, digital elevation models, and data obtained from topo-cadastral measurements that were previously performed by the authors using the total station. To these were added photos taken by the authors during several field campaigns (2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, and 2021) to capture beauty of the railway and the landscapes it crosses. A database was created in File Geodatabase format. This type of database is used to store attributes related to entities represented in vector form. Vector data were obtained as a result of field measurements using modern technologies (using a total station), after digitization or from data in raster format following the vectorization operation. The data were organized in vector and raster format [50,98]. Vector data included polygons, polylines, and points along with their attributes [50,98]. The polygon dataset included characteristics such as vegetation distribution, land use, boundaries of territorial administrative units, roads, constructions; the polyline dataset contains the railway itself, water bodies, etc.; the set of points includes the distribution of heritage assets, points of interest located along the route (viaducts, tunnels, etc.).

3.2.3. Data Processing

Data processing consisted of analyzing and overlapping data, customizing the thematic map. In order to draw the limits of the route of the historical railway, criteria applied in other studies dedicated to the delimitation of the heritage corridors were used: natural landscape boundaries (e.g., ridge boundaries, water boundaries), cultural boundaries based on the definition of a cultural buffer that allows delimitation based on the distribution of cultural heritage elements around administrative centers [50,78], the sphere of cultural influence: the area seen as a cultural whole [61] and the administrative boundaries [50,78]. Along the linear railway site were the following administrative territorial units: two towns, Oraviţa and Anina, and two communes, Ciudanoviţa and Goruia.

A geodatabase was created to represent the railway and the associated heritage elements (stations, viaducts, bridges, depots), as well as other cultural heritage elements, using the ArcGIS digital platform, specifically the ArcGISPro application 2.9.3. The importance of creating a geospatial database is correlated with the need to assess the complexity of the railway heritage, facilitating its integration with other elements of natural and cultural heritage in a coherent form. There is currently special interest in integrating geoinformation data into heritage databases through the use of GIS software that has the ability to correlate geographical and alphanumeric information, also extremely useful in representing heritage elements along a historical route whose distribution in the territory is dispersed [62]. Based on the creation of the geodatabase, a model was elaborated that reflects the geographical reality, the emphasis being on the representation of the typology of the railway heritage assets. At the same time, particularities of the geographical framework represented by high values of the declivity were highlighted.

The qualitative method (for site research) has been applied in various studies focused on railway [29,44] or industrial heritage [95,97] because it allows for the use of various investigative techniques, based on which the researcher can analyze and evaluate in depth a case study from the perspective of the perceptions of the community [44,95,97], the scenic authenticity of the place, and the tourist gaze [44]. The active participation of the researcher is followed by a critical interpretation of the results. The authors conducted on-site research to observe the particular characteristics of the historical Oraviţa–Anina railway line during five field campaigns.

Additionally, the authors analyzed, based on participatory observation, the community’s perception of the tourist use of the railway and the behavior of tourists. Thus, discussions were held in the form of semistructured interviews with members of the local community, including railway employees, focused on analyzing their perception concerning the tourist reuse of the railway. Eighty-six semistructured interviews were conducted in the two terminus stations, the towns of Oraviţa and Anina. The duration of the semi-structured interviews was 35–45 min. Thirty-nine interviews took place in July and forty-seven took place in September 2021.

The semistructured interview was organized around the following open questions:

1. Do you consider that the Oraviţa–Anina railway defines the tourist image of the town where you live?

2. How do you appreciate the reuse of the railway as a tourist objective?

3. What are the elements that draw tourists to frequent the tourist railway?

4. Mention at least one favorable element and one weak point regarding the way of capitalizing the railway as a tourist objective.

The two towns have similar populations by age group: 0–19 years: Anina 20% and Oraviţa 18%, respectively; young population (20–29 years): 27.6% and 27%, respectively; adult population (30–64) 37% and 39%, respectively; and population aged 65 and over: 15.4% and 16%, respectively (statistical data calculated by authors, source: National Institute of Statistics) [99]. Regarding the age of respondents, the young population (up to 18) represents 34.6% (including people who have reached age of 18), the adult population 44.1%, and the elderly population 21.3%. The educational status of the respondents was quite varied, with more than half having secondary education. The respondents had varied occupations, which was relevant to the study (Table 1).

Table 1.

The social and demographical characteristics of respondents.

As participating observers, the role of the authors was also to critically analyze the behavior of tourists at the stations and during the train journey. The observation of the tourists’ behavior was made by the researchers as “bystanders” [44], who evaluated in a detached way the degree of appreciation of the tourist experience.

4. Results

As mentioned earlier, the authors assessed the value of the historical Oraviţa–Anina railway using six key attributes adapted to the railway heritage, as proposed by Xie (2006) [77], also called critical success factors [12], as well as a number of associated indicators [61], in order to quantify its tourist attractiveness.

4.1. The Potential of the Railway

The potential of the railway was assessed on the basis of its multiple types of value.

(a) Historical significance. The early construction of the Oraviţa–Anina railway (1847–1863) was related to the need to transport coal mined in the southern part of the historic province of Banat (Anina mining basin) to the Danube port Baziaş, and from here, by ships on the Danube, to Vienna. Coal was used mainly by large Danube shipping companies, the best known of which was the Donau Dampfschiffahrt Gesellschaft (D.D.S.G., established in 1829) [7]. The transport of coal from Anina to Oraviţa was carried out with difficulty until the construction of the railway, using carts [100]. The intensification of the coal exploitation from the Anina mine and the discovery of new coal deposits (at Gârlişte and Jitin) necessitated the building of the Oraviţa–Anina line. The Austrian professor Franz Xavier Riepl elaborated the first project of a railway network for the Austrian Empire, between 1829 and 1835, which also included a proposal to build a line connecting the Anina mining basin with the Danube port Baziaş [72]. Initially, the Oraviţa–Baziaş railway segment was built (started in 1847 and opened in 1854, originally used for the transport of coal and other goods from Oraviţa to the Danube; from November 1, 1856, it was also used for passenger transport). Later, the Oraviţa–Anina railway segment was built at the initiative of the director of the Banat mines, the aulic councilor Gustav von Gränzestein. However, the costs of building a standard gauge railway line were quite high. If we also take into account the fact that the line was going to cross a very difficult route through the mountains from Anina to Oravița, we understand why, at the beginning, a less expensive solution was chosen for this line. Initially, the railway had two segments: the first on the route Anina (Steyerdorf is the German name) to Lişava with horse traction, with a length of 25.7 km, which was used for the crossing of the sections with large slopes; this segment started in 1847, and was completed in 1854; the second segment, the Lişava–Oraviţa distance, with a length of 6.8 km, was a railway with steam locomotive traction. The traction on the provisional line Lişava–Oraviţa, with a different route than today, was ensured with type 1B–n2 locomotives, of the same type as those used on the rest of the line to Baziaş [7,72]. Part of the route of this narrow line can still be found today. Between Anina and Gârliște, one can see the tunnels of the former line next to the tunnels of the normal gauge line, then, near the Gârliște station, one can still see the embankment of the former line, as well as the tunnel, and the route can also be seen through the forest to Jitin Valley. Here, the narrow line ran much higher up the slope on the right bank of the valley. At the end of the embankment, towards Ciudanovița, there was also a shaft through which the wagons were lowered into Jitin Valley, to then reach Lișava station [100]. After 1852, with the increase in performance of steam traction, the decision was made to change the construction method of the horse-drawn segment.

Due to a financial crisis, the imperial authorities decide to sell to the Royal Privileged Caesar–Austrian State Railway Company (StEG) its mining, metallurgical, and forestry properties in Banat and Bohemia, together with a 90-year concession for the construction and use of a railway network. Due to the difficulty of transporting coal on the route by horse traction, StEG assumed the reconstruction of the railway project from Lişava to Anina by arranging a new route on which steam locomotives would be used. Between 1861–1863, the construction of the new normal railway with steam traction on the Oraviţa-Anina route was completed [72].

(b) Technological value.

The route of the railway crosses mountainous areas around Anina and on the Lişava–Gârlişte segment, later passing through a hilly area near Oraviţa town, with a level difference of 339 m and very small curvature lines. Thus, from a technical point of view, the difficulty of the route required the construction of a prototype steam locomotive and wagons with a particular structure. The construction of the locomotive and wagons was designed with a smaller distance between the axles with a length and a light weight of only 42 tf, so as to avoid train derailment in areas with high declivity for reasons of railway safety [7]. This limits the maximum speed to 20 km/h, and even lower in segments with high declivities. The curves, numbering 160, represent 70% of the total length of the route; 129 curves (81%) have a radius of curvature of less than 200 m, representing 20 km in total [100]. Due to the very small radii of curvature of the route, some of which are only 114 m, and the slopes of up to 20 mm/m, the Oraviţa–Anina line is very similar to the famous Gloggnitz–Mürzzuschlag (Semmeringbahn) mountain line from Austria, which crosses the Alps Mountains through the Semmering pass (897 m altitude) [7]. This is why the Oraviţa–Anina line was called the “Banatian Semmering” [7,72,74,101].

The locomotive prototype was used only on this line and marked the history of rail transport. Due to their originality, the first steam locomotives that ran on the Oraviţa-Anina line, figures in the great treaties of steam traction. Due to the uniqueness, conferred by the orginal constructive solutions adopted, the first locomotive used on this railway was named no. 500 STEYERDORF (German name of Anina town).

It was presented at two universal exhibitions, in 1862 in London and later in 1867 in Paris, where it attracted great interest from specialists [7]. Thus, the first steam locomotive was designed in 1861 by the Austrian engineer Pius Fink, who worked in the Vienna locomotive factory of the StEG Company. In order not to exceed the axle load imposed, Fink designed an articulated tender locomotive with five coupled axles, similar to those designed by the Austrian engineer Wilhelm Freiherr von Engerth for the railway crossing the Semmering Pass in Austria. Engineer Pius Fink devised an ingenious way of coupling the wheels on axles in the form of a parallelogram, and an injector of his own design [7] (pp. 90–91). Through this construction, the tender frame took over part of the weight of the boiler, and the locomotive could fit in curves with a radius of up to 90 m. In order not to exceed the maximum permissible load of 9.5 t/axle, the water reserve was no longer placed in the tender, but in a special wagon, on two axles, insulated against frost, attached immediately after the locomotive. Because the maintenance of this type of locomotive was difficult and expensive, also presenting the inconvenience of having a relatively high weight, in 1891, due to the increase in train tonnage and traffic, new locomotives-tender were built on the Oraviţa–Anina line, with four coupled axles (compared to five axles in the first model), making them more modern and stronger [7]. In the history of the railway networks, there are few lines that required the construction of special locomotives and therefore the Oraviţa–Anina line is of special interest. Between 1919 and 1922, the Romanian railways (CFR) bought several E-h2 type locomotives, necessary to replace low-powered locomotives of old construction. The kkStB series 80 locomotive (type E-h2) was developed by the famous Austrian engineer Karl Gölsdorf and was an improvement on the kkStB 180 series locomotives (the prototype built in 1900 at Wiener Lokomotivfabriks AG, Floridsdorf). For this purpose, the Austrian type 80 was chosen, being in operation on the lines on Austria, with excellent results, since 1909 [7]. The locomotives of Romanian railways were initially supposed to receive numbers 5001–5010 (the order from 1919), but, with the introduction of the new numbering scheme in 1920, they were included in the 50.001– 50.080 series. Starting in 1956, there were new, more powerful CFR 50.000 series locomotives as passenger traffic increased. The Oraviţa depot was the last “bastion” of the CFR 50.000 series. The last CFR 50.000 series locomotives were withdrawn from service in 1981, and most of them were scrapped by 1988 (Figure 4a,b). Only two copies of the series were preserved: 50.025 (StEG 4483/1921), at the locomotive museum in Reşita, and 50.065 (StEG 4498/1921), in front of Oraviţa station. To repair the locomotive 50.065, in May 1994 at IMMR 16 February Cluj-Napoca, the boiler and other parts from the locomotive 50.078 were used, kept especially for this purpose by the late engineer Nicolae Călina, from the Traction Division Timişoara.

Figure 4.

(a,b) The four-axle steam locomotive prototype. Source: Merciu Florentina-Cristina.

It is important to mention that, on the Oraviţa–Anina line, the traffic conditions did not undergo significant changes compared to the opening year. The only notable change is the replacement of steam locomotives with dieselelectric one, on four axles, having a special construction, in the sense that they were designed especially for this line, later also being used on industrial lines. The diesel electric locomotives, originally designed by Electroputere Craiova Plant as locomotives of the 040-DA series, were manufactured at the 23 August Plant in Bucharest using component parts from the 1250 HP diesel–hydraulic locomotives in production (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The diesel locomotive currently in use on the Oraviţa–Anina railway. Source: Merciu Florentina-Cristina.

The passenger carriages were also modified. The old Hungarian wagons built at the end of the 19th century, being very old, were replaced by other short wagons. Additionally, particular to this line, the comfort and safety of operation of the wagons raised problems, so the Romanian railways modified the new wagons on four axles, unlike the old wagons that only had two axles [7,8]. The new carriages keep the interior arrangement of the timeThe construction of the line required artisanal engineering works by architects Karl Maniel and Iohan Ludvic Dolhodir [7,100]. Along the 33.4 km route, support walls and cuts in the mountain rock were made over a length of 21.3 km [72]. The engineering works are represented by 14 tunnels with a total length of 2084 m, 10 viaducts totaling 842 m, and numerous bridges and footbridges [7] (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Spatial distribution of railway engineering elements along the Oraviţa–Anina railway transposed on a 3D terrain model. Source: Processed by the authors.

Of note are the Racoviţă viaduct, with 11 openings, 115 m long, and located at a height of 26.5 m; and the Jitin viaduct, with seven openings, measuring 37 m high and 130.8 m long (Figure 7a). The longest tunnel is Gârlişte, at 661 m [72]. In 1978, the number of counter rails placed in difficult curves increased, increasing the speed from 15 to 20 km/h [8] (p. 41). Italian stonemasons also took part in the construction of the railway, using a mortar similar in composition to the Roman one, which explains the endurance of the tunnels and viaducts [74].

Figure 7.

(a) Jitin viaduct which crosses the homonymous valley. (b) Schlucht viaduct (near Anina). Source: Dorobanţu Mircea.

The Lişava–Gârlişte route segment is considered to be the most spectacular along the railway line. It has a high density of engineering works, with 8 tunnels and 25 footbridges for water drainage, and two bridges. This segment, considered to be the point of maximum technical performance of the entire railway [74], with a length of 11,139 m, is mostly traveled through on a slope of 10,942 m [100]. The maximum slope is 21‰ (with short sections of 23‰) for 5188 m. The length of the support walls is 2572 m, and the length of the rock excavations is 7988 m. [100]. The tunnels, viaducts, and bridges are artisanal engineering works because they were dug by hand with chisel, hammer, and drill (Figure 8a,b), in the absence of dynamite, which was invented three years after the completion of the works.

Figure 8.

(a) Tunnel dug into the rock. Source: Dorobanţu Mircea. (b) Succession of technical works near Anina. Source: Merciu Florentina-Cristina.

The rocks in the vicinity of the line break off into slabs. For digging, deep holes were made with a drill in the area where slabs were separated, then steel wedges were inserted by hammering into these holes. The wedges, being of a larger diameter than the hole, push the stone slabs apart, causing them to break and fall. The stone slabs were removed using rudimentary cranes with wooden beams that had fixed and movable pulleys.

(c) Architectural value.

The railway stations and other outbuildings along the route (Oraviţa depot, offices for rail staff, waiting rooms) stand out for their architectural value given their shape, proportions, and general design qualities, elements that give them the style of railway buildings. Due to their historical and architectural value, they have been classified as historical monuments along with the engineering constructions. Oraviţa and Anina stations have special architectural value. Oraviţa is the oldest railway station in Romania and was built according to the plan of the engineer Karl Bach [102]. The construction of Oraviţa station was completed in 1847 [75]. The building was equipped with an elevator. The elevator no longer exists, but the space where it was still exists. There is also a passage from the station to the platform above the street level, to ensure access of the station staff to the platform—a first for the period [7]. The Oraviţa train station has perforated wooden gussets on wooden pillars that support the ridge of the roof of the main façade (Figure 9a,b).

Figure 9.

Oraviţa station: the simple architecture is marked by gussets with floral motifs: (a) 2010 (b) 2021. Source: Merciu Florentina-Cristina.

The perforated wooden gussets have a decorative role, having an elaborate shape and floral motifs, but also a function of resistance to the upper part of the pillars. We can note the use of more complicated cuts, as well as the alternation of “gaps” and “full” elements in the drawing, which leads to a realization of real lacework in wood, with obvious aesthetic appeal (Figure 9a).

Additionally, another way to decorate the building is with plaster applications made in relief (“stuccos”), like above the window frame. Stuccos are made up of geometric motifs (a rosette placed centrally between two broken lines). Gussets and stuccos have been highlighted in recent years, when the station of Oraviţa was renovated, with a lighter color (white) than the color applied on the main facade (yellow) (Figure 9b).

Anina train station, of elongated shape, is built of brick, which is also reminiscent of the construction of old industrial buildings. The brick gives the station an austere and elegant look (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Anina station is built of brick. Source: Merciu Florentina-Cristina.

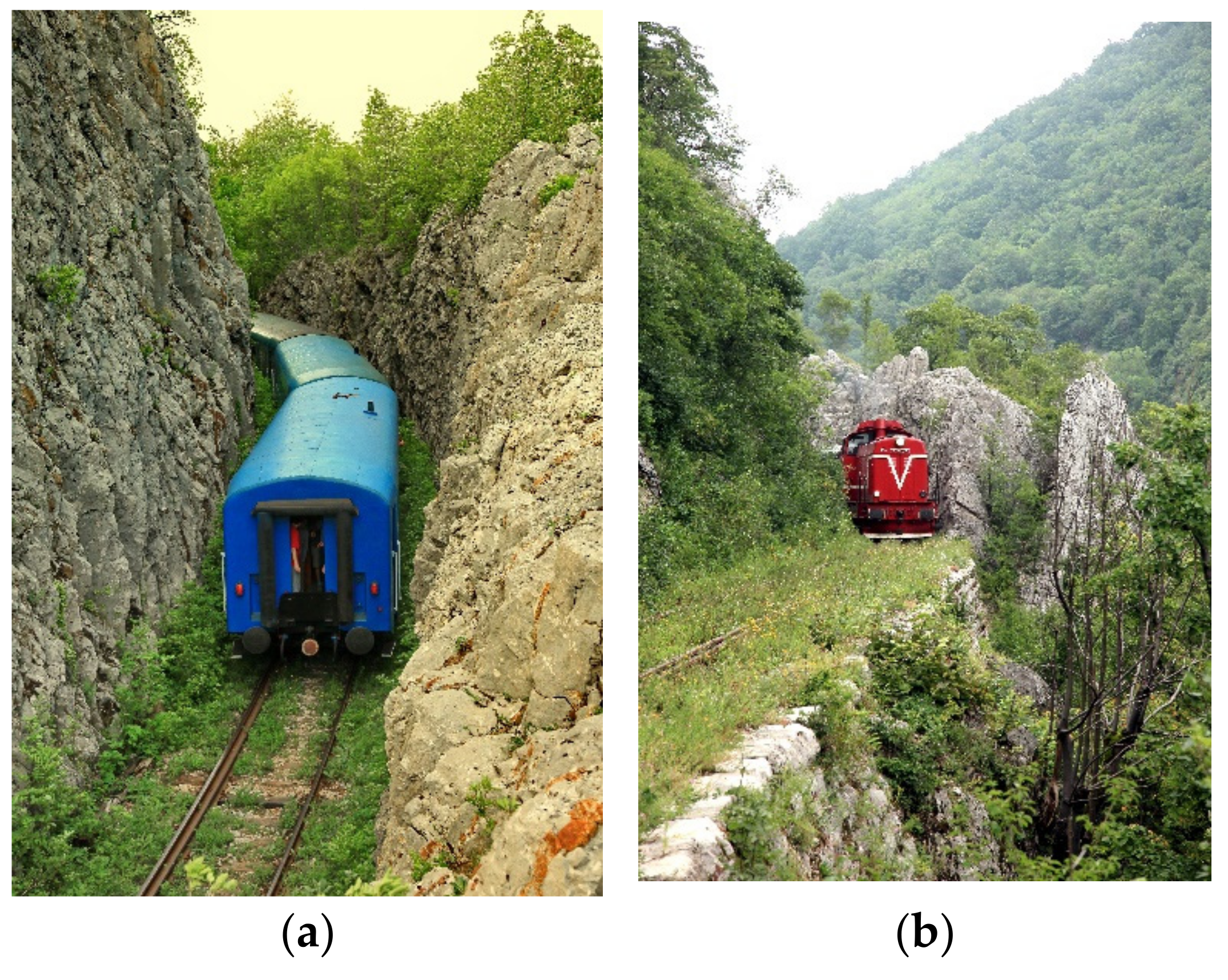

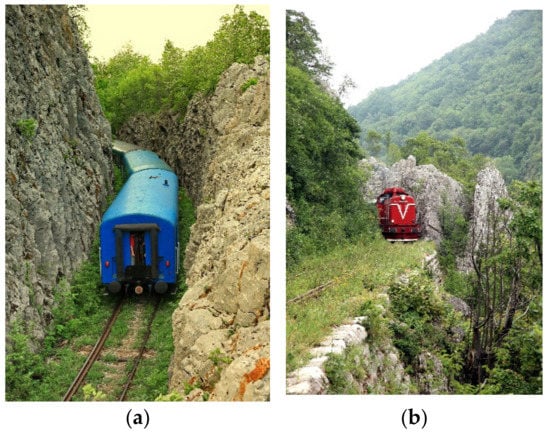

(d) Aesthetic value and the relationship of the railway with the landscape.

The Oraviţa–Anina railway line has significant aesthetic value due to the shape and architectural details of the railway buildings, as well as to the picturesque landscapes along the route. From Oraviţa, the route goes through a succession of landscapes, hilly to mountainous. The Lişava–Anina route segment has the highest landscape value because it crosses an area of mountains that have limestone outcrops. The train also crosses narrow areas delimited by limestone vertical walls (Figure 11a,b).

Figure 11.

Karst landscape along the Oraviţa–Anina railway. (a) A train specific to the line crossing the limestone cliffs at the entrance to Jitin Valley from Ciudanoviţa (Source: Dorobanţu M.) (b) Electric diesel locomotive 69-003-9 with the passenger train at the exit from the limestone cliffs to Jitin Valley from Ciudanoviţa. Source: Dorobanţu Mircea.

Of the length of the railway, two-thirds crosses mountainous areas, through forest or limestone cliffs.

(e) The economic value.