Developing an Evidence-Based Framework of Universal Design in the Context of Sustainable Urban Planning in Northern Nicosia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Universal Design

2.2. Urban Design Parameters

2.3. Social Sustainability

3. Material and Methodology

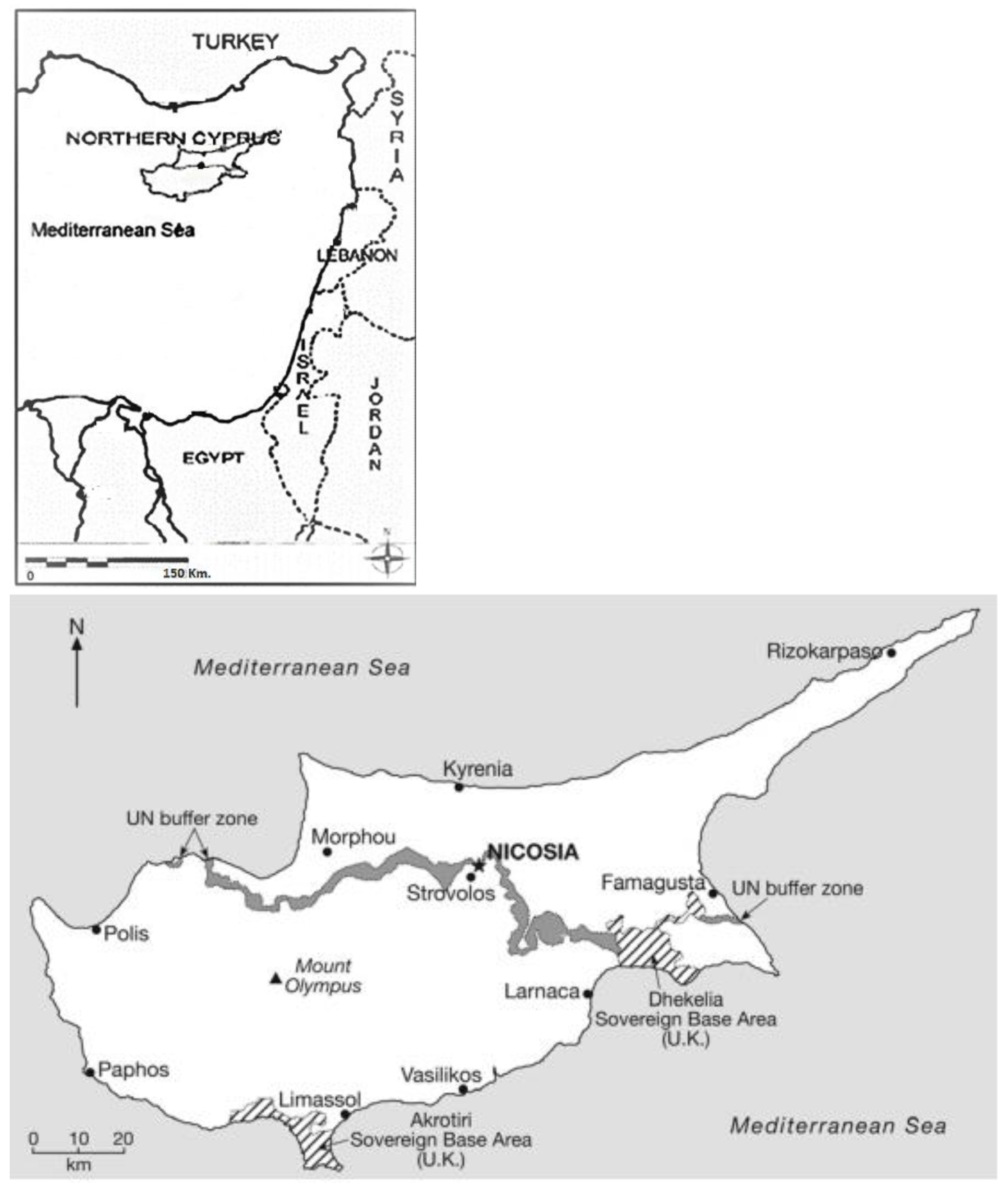

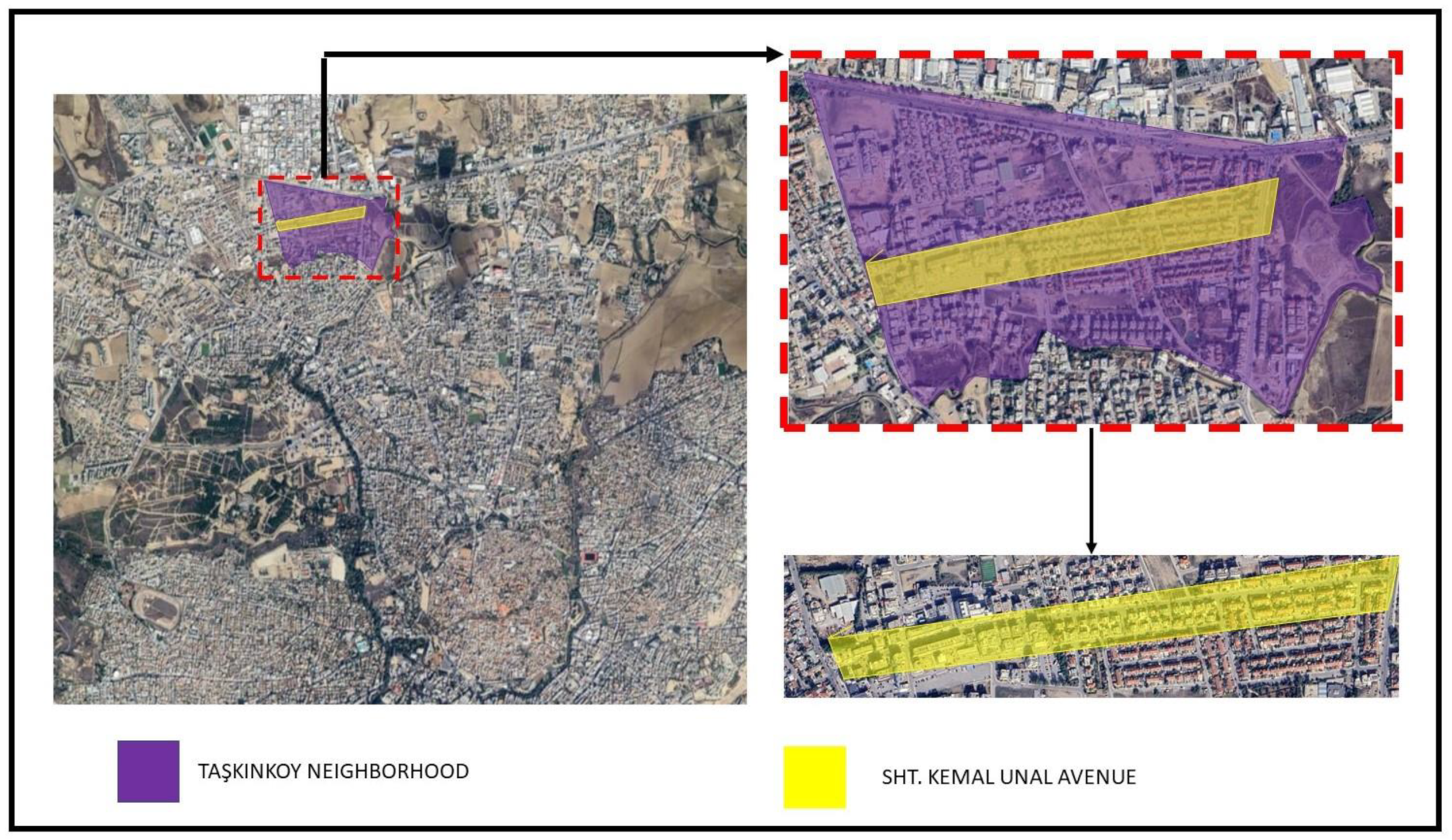

3.1. Research Area

3.2. Research Design

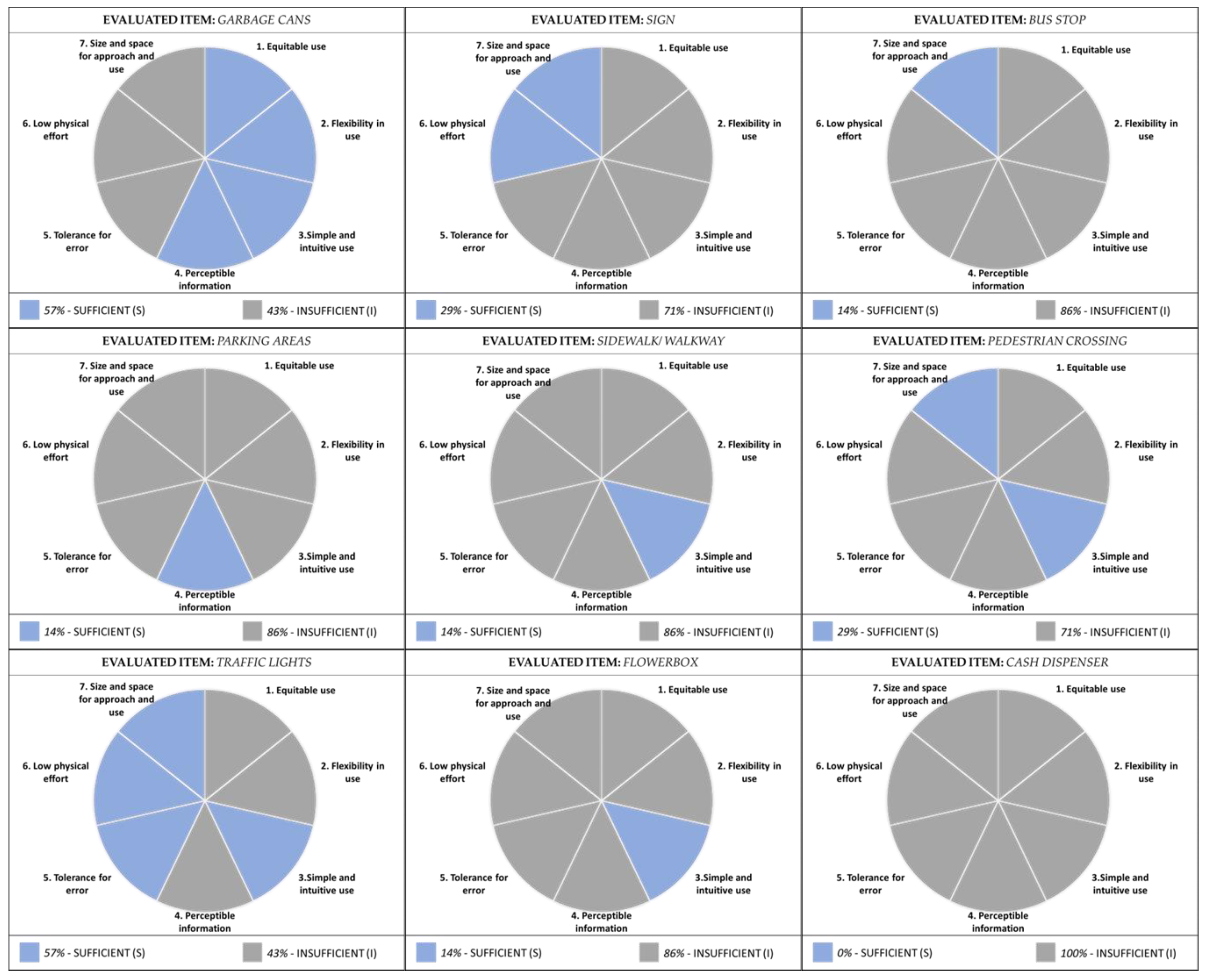

- Garbage cans

- Signs

- Bus stops

- Parking lots

- Sidewalks/walking paths

- Pedestrian crossing

- Traffic lights

- Flowerbox

- Cash dispenser

4. Findings

Limitations of the Study

| Urban Space Evaluation Form | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neighborhood Name: TAŞKINKÖY | Urban Spaces Name and Type: Sht. Kemal Ünal Avenue | |||||||

| Evaluated Item | Visual (S) | UD Principles | Evaluation | Sufficient (S)/Insufficient (I) | ||||

| Garbage Cans |  | Equitable use | Garbage cans can be used by different profiles of users, including disabled ones. | S | ||||

| Flexibility in use | They vary in material, size, and location. For this reason, it offers users opportunities for different needs. | S | ||||||

| Simple and intuitive use | Its function is easily understood by everyone. | S | ||||||

| Perceptible information | It is made of material with a contrasting color to its surroundings, increasing its perceptibility. | S | ||||||

| Tolerance for error | Users may have instant accidents because of the location. | I | ||||||

| Low physical effort | Short individuals or children cannot reach easily. | I | ||||||

| Size and space for approach and use | They are not suitable for the approach and use of children, short individuals, or wheelchair users. | I | ||||||

| Sustainable Urban Design Parameters | Accessibility | Connectivity | Walkability | Safety | Adaptability | Legibility | Comfort | |

| Score |

| x | o | x | x | o | o | o |

| Evaluated Item | Visual (S) | UD Principles | Evaluation | Sufficient (S)/Insufficient (I) | ||||

| Signs |  | Equitable use | They cannot be used by illiterate and visually impaired individuals. | I | ||||

| Flexibility in use | Since the information board is written in two languages (Turkish and English), individuals can choose the one that suits them. However, visually impaired and illiterate individuals cannot understand the explanation. | I | ||||||

| Simple and intuitive use | The signs and keys on the device are self-explanatory. However, there is no explanatory tool for the visually impaired. | I | ||||||

| Perceptible information | Information is not perceivable by all individuals. | I | ||||||

| Tolerance for error | Due to its location on the pavement, it is dangerous for people who walk distractedly or have poor eyesight. | I | ||||||

| Low physical effort | It is sufficient to press the keys for use easily. | S | ||||||

| Size and space for approach and use. | It is suitable for the approach and use of various users. | S | ||||||

| Sustainable Urban Design Parameters | Accessibility | Connectivity | Walkability | Safety | Adaptability | Legibility | Comfort | |

| Score |

| ✓ | o | x | x | ✓ | o | ✓ |

| Evaluated Item | Visual (S) | UD Principles | Evaluation | Sufficient(S)/Insufficient (I) | ||||

| Bus Stop |  | Equitable use | There is only one type of seating element. (h:50cm. w: 122cm. d: 40 cm.) | I | ||||

| Flexibility in use | A pavement ramp is not considered to overcome the level difference in order to reach the bus stops. | I | ||||||

| Simple and intuitive use | Necessary markings and directions have not been made so that the stops can be seen from a distance. | I | ||||||

| Perceptible information | There is no information board at the bus stops. | I | ||||||

| Tolerance for error | Since transparent material is used, it poses a danger to users visually impaired. | I | ||||||

| Low physical effort | Bus stops cannot be accessed without physical effort by users with wheelchairs. There is no ramp and textured surface. | I | ||||||

| Size and space for approach and use | Sufficient space has been left for wheelchair users or parents with strollers to stand. | S | ||||||

| Sustainable Urban Design Parameters | Accessibility | Connectivity | Walkability | Safety | Adaptability | Legibility | Comfort | |

| Score |

| ✓ | x | x | x | x | ✓ | x |

| Evaluated Item | Visual (S) | UD Principles | Evaluation | Sufficient (S)/Insufficient (I) | ||||

| Parking Areas |  | Equitable use | Parking spaces parallel to the road do not offer equal usage for all individuals. There is no car parking area for disabled users. | I | ||||

| Flexibility in use | Disabled parking space has not been arranged considering different types of users. | I | ||||||

| Simple and intuitive use | The parking lots along the street are not clearly distinguishable and understandable in terms of materials and design. | I | ||||||

| Perceptible information | There are information signs and payment points about parking times and pricing on the street. | S | ||||||

| Tolerance for error | The floor covering is deformed. It is dangerous for users. | I | ||||||

| Low physical effort | A curb ramp is not considered for access from the parking lot to the sidewalk. | I | ||||||

| Size and space for approach and use | Except for the manoeuvring area, it does not comply with the parking dimensions (250/500 cm.) determined for the vehicle. | I | ||||||

| Sustainable Urban Design Parameters | Accessibility | Connectivity | Walkability | Safety | Adaptability | Legibility | Comfort | |

| Score |

| ✓ | o | o | x | x | o | o |

| Evaluated Item | Visual (S) | UD Principles | Evaluation | Sufficient (S)/Insufficient (I) | ||||

| Sidewalk/Walkway |   | Equitable use | User diversity has been neglected. Sidewalk ramps have not been created and textured surfaces have not been used. The pavement surfaces are partially destroyed. | I | ||||

| Flexibility in use | Sidewalks along the street differ in terms of material size. Different users have not been taken into account, design has not been made according to user needs, such as pavement. | I | ||||||

| Simple and intuitive use | Pavement areas are distinguished. | S | ||||||

| Perceptible information | The property area, pedestrian area, and safety lane have not been determined separately. | I | ||||||

| Tolerance for error | Different elements, such as lighting in the pavement, cover the walking area and can cause an accident. | I | ||||||

| Low physical effort | There are no sidewalk ramps that help to ensure the continuity of the sidewalks. | I | ||||||

| Size and space for approach and use | Although the user density is the same, the sidewalk widths vary along the street. | I | ||||||

| Sustainable Urban Design Parameters | Accessibility | Connectivity | Walkability | Safety | Adaptability | Legibility | Comfort | |

| Score |

| x | x | x | x | x | o | x |

| Evaluated Item | Visual (S) | UD Principles | Evaluation | Sufficient (S)/Insufficient (I) | ||||

| Pedestrian Crossing |  | Equitable use | It cannot be used equally by all users due to deficiencies and errors in physical arrangements. | I | ||||

| Flexibility in use | User diversity is not taken into account. | I | ||||||

| Simple and intuitive use | It can be easily perceived from a certain distance because of the warning lines drawn on the floor. In addition, there are speed limiter ramps for vehicles located close to the pedestrian crossing. In order to be perceived at night, flashing warning lights have been considered, despite their location being inside the pedestrian crossing. | S | ||||||

| Perceptible information | There are no guide tracks for visually impaired individuals. | I | ||||||

| Tolerance for error | It may cause accidents due to its damaged ground. In addition, accidents may occur in terms of the location of the flashing warning lights. Positively, there are ramps on two sides of the crossing decreasing the driver speed. | I | ||||||

| Low physical effort | The junction of the sidewalk and the pedestrian crossing is not at the same level and a ramp is not considered. | I | ||||||

| Size and space for approach and use | It is suitable for all users in terms of its size. (w = 400 cm) | S | ||||||

| Sustainable Urban Design Parameters | Accessibility | Connectivity | Walkability | Safety | Adaptability | Legibility | Comfort | |

| Score |

| x | ✓ | ✓ | x | x | o | o |

| Evaluated Item | Visual (S) | UD Principles | Evaluation | Sufficient (S)/Insufficient (I) | ||||

| Traffic Lights |  | Equitable use | It is positioned to control vehicle traffic. Pedestrians using the street are not considered. | I | ||||

| Flexibility in use | There are no warning systems suitable for user diversity. | I | ||||||

| Simple and intuitive use | The colors of the lights have international validity. It is understood equally by all individuals. | S | ||||||

| Perceptible information | When approaching the traffic lights, there is no information sign stating that there is a traffic light at a certain distance. | I | ||||||

| Tolerance for error | Red light duration is arranged so that vehicles coming from different directions do not intersect. | S | ||||||

| Low physical effort | As it is automated, it does not require any physical power. | S | ||||||

| Size and space for approach and use | Light heights have dimensions that can be seen by users in the vehicle from a certain distance. (h = 346 cm.) | S | ||||||

| Sustainable Urban Design Parameters | Accessibility | Connectivity | Walkability | Safety | Adaptability | Legibility | Comfort | |

| Score |

| ✓ | ✓ | o | ✓ | o | o | o |

| Evaluated Item | Visual (S) | UD Principles | Evaluation | Sufficient (S)/Insufficient (I) | ||||

| Flowerbox |  | Equitable use | Since the flowerboxes cover the walking area on sidewalks, it is not suitable for visually impaired individuals or for individuals walking side by side as a group. | I | ||||

| Flexibility in use | Flowerboxes can be used as a divider and surrounding element by positioning the long side of them parallel to the road. | I | ||||||

| Simple and intuitive use | Because of the positions of the flowerbeds, the connection points of the vehicle road and the sidewalks are controlled and can be distinguished. | S | ||||||

| Perceptible information | It is not designed in a contrasting color with the environment. For this reason, its detectability is low. | I | ||||||

| Tolerance for error | Location of the flowerboxes in the pavement cover the walking area, and they can cause an accident. | I | ||||||

| Low physical effort | Since it covers the walking area, it causes changes in direction when walking. It is not suitable in terms of low physical effort. | I | ||||||

| Size and space for approach and use | Its height is not sufficient to be perceived by individuals. (h: 42 cm) | I | ||||||

| Sustainable Urban Design Parameters | Accessibility | Connectivity | Walkability | Safety | Adaptability | Legibility | Comfort | |

| Score |

| o | ✓ | x | x | o | o | o |

| Evaluated Item | Visual (S) | UD Principles | Evaluation | Sufficient (S)/Insufficient (I) | ||||

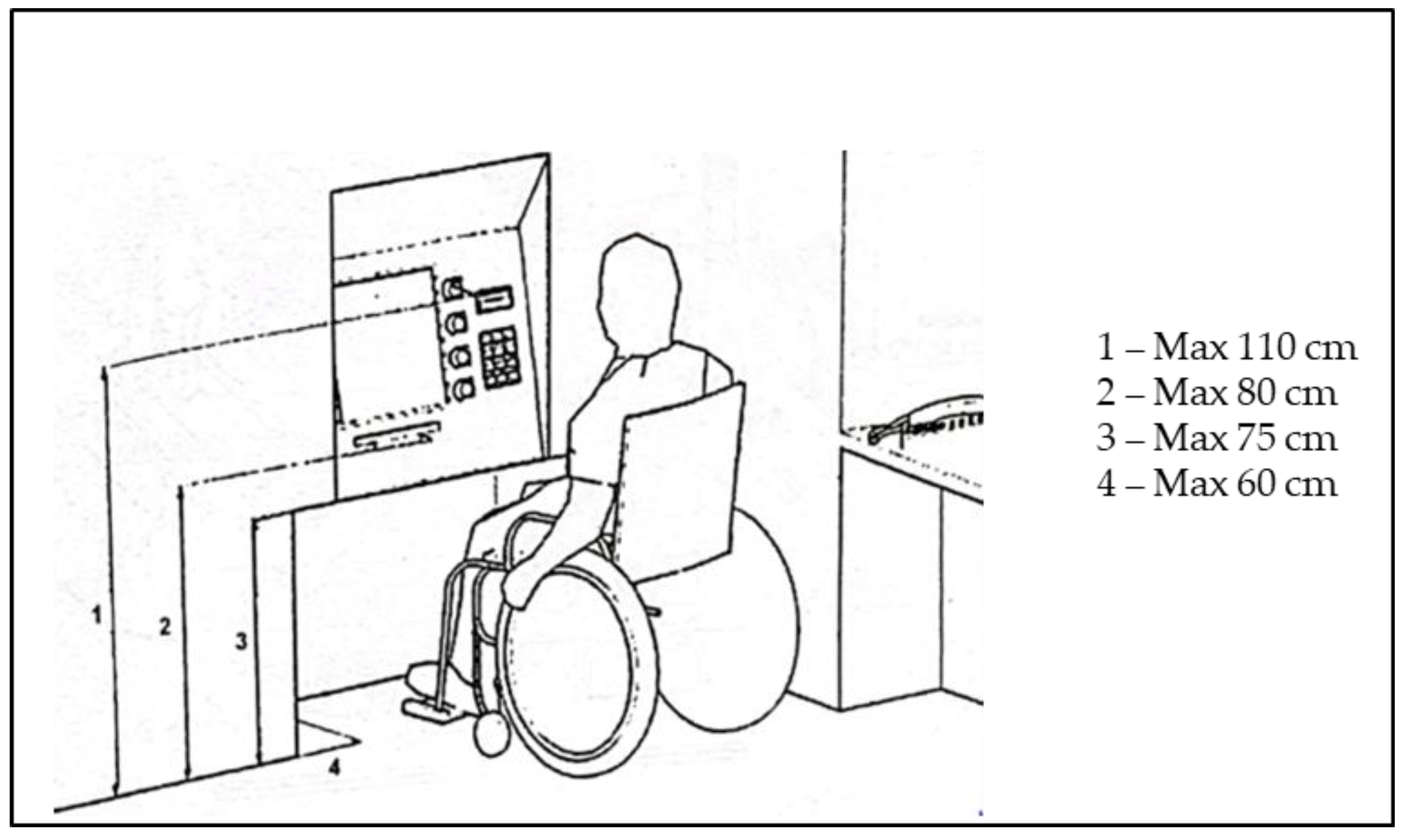

| Cash Dispenser |  | Equitable use | Due to its dimensions and the level difference between the pavement, it cannot be said to be of equal use. | I | ||||

| Flexibility in use | The user is not offered a choice in terms of dimensions for using machine. The principle of flexible use has been neglected. | I | ||||||

| Simple and intuitive use | Although the operation screen and keys are suitable for simple and intuitive use for different profile of users, illiterate individuals and/or visually impared cannot use it. | I | ||||||

| Perceptible information | Information for using is not perceptible for illiterate individuals or the visually impaired. | I | ||||||

| Tolerance for error | The level difference between the pavement and the access platform to the device can cause accidents. | I | ||||||

| Low physical effort | The level difference for accessing the device indicates that it is not suitable for the low physical effort principle. | I | ||||||

| Size and space for approach and use | Due to its size and the access platform, it is not suitable for all individuals in terms of approach and use. | I | ||||||

| Sustainable Urban Design Parameters | Accessibility | Connectivity | Walkability | Safety | Adaptability | Legibility | Comfort | |

| Score |

| x | o | o | x | x | o | o |

| Urban Space Items | Size | TSI Standards | A/I |

|---|---|---|---|

| Garbage Cans | height: 130 cm | height: 90–120 cm | I |

| Signs | height: 200 cm | starting point height: 105 cm end point height: 195 cm | I |

| Bus Stops | sitting element height: 50 cm | sitting element height: 41–46 cm | I |

| thick, non-matte, colored, reflective strips: not available | thick, non-matte, colored, reflective strips height: 100–140 cm | I | |

| Parking Lots | width: 202 cm length: 472 cm | width: 250 cm length: 500 cm | I |

| Sidewalks/Walkway | width: 145–856 cm (variable) | width: at least 150 cm | I |

| Pedestrian Crossing | width: 400 cm | width: min. 300 cm | A |

| Traffic Lights | Height: 346 cm | height: 450 cm | I |

| Flowerbox | height: 42 cm | height: 70 cm | I |

| Cash Dispenser | card point height: 121 cm cash point height: 100 cm | max. card point height: 110 cm max. cash point height: 80 cm | I |

5. Discussion

5.1. The Stops

- Necessary markings and directions should be made so that they can be easily found and seen from a distance.

- The stops are located inside the pavement at present. They should be positioned outside the pavement width and should not block the walking area.

- Since transparent material is used, two 15 cm thick non-matte, colored, reflective strips should be attached 100–140 cm above the surface in order to not pose a danger to users with vision problems.

- At each stop, there should be a legible and illuminated information sign stating which public transport vehicle the stop belongs to, the route number of the vehicle, the route and the name of the stop.

- The height of this plate from the ground must be at least 220 cm. Informative boards at the stops should be at a maximum height of 110–130 cm. On these boards, the route plan of the public transportation vehicles that will come to that stop, the closest taxi stand to that stop, and important telephone numbers such as emergency health should be listed. The location of the stop should be indicated by an arrow on the route plan, and other public transport routes on the route and, if any, transferable stops should be highlighted. There should be a city map, divided into zones by color, showing important public buildings and main streets. The information on the board should be designed taking into account the visually impaired, by using letters with large buttons, embossed city maps and route plan, and if necessary, voice notification mechanisms should be used.

- Necessary markings and directions should be made so that the stops can be easily found and seen from a distance.

- If transparent material is used at the stops, two 15 cm thick glossy, colored, reflective strips should be attached 100–140 cm above the ground on these surfaces in order to not pose a danger to visually impaired pedestrians.

- The sitting element height of the bus stop should be 41–46 cm.

5.2. Sidewalks/Walkway

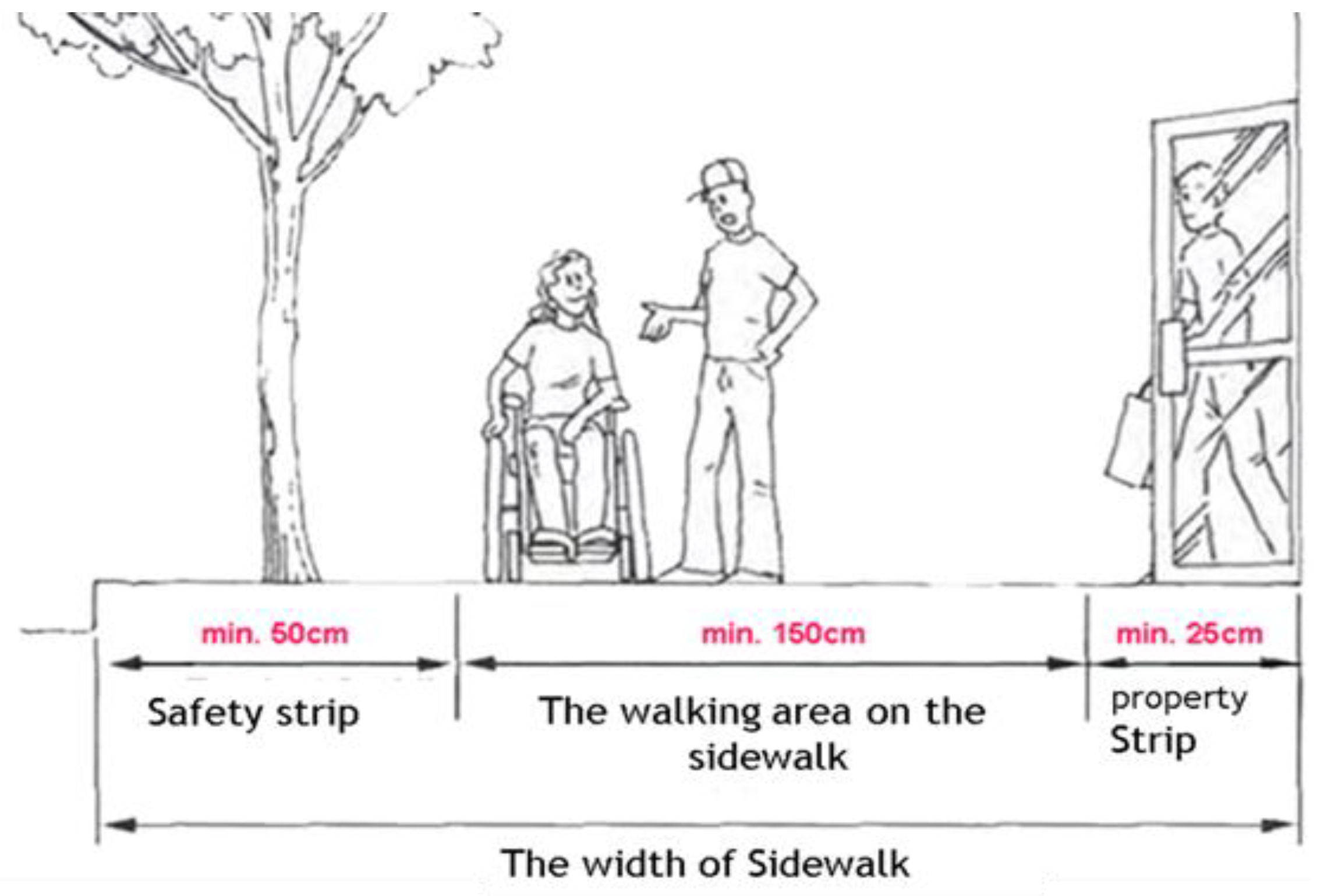

- They must be designed with the safety strip, sidewalk walking area and property area regulations given in the laws and regulations examined (Figure 6).

- The urban furniture (signs, flowerpots, trash cans, lighting elements, etc.) should be located within the safety strip area seen in the sidewalk section given in Figure 6.

- Damage to the sidewalk surface must be repaired and they should be covered with non-slip flooring materials without gaps.

- In the walking area of the sidewalk given in Figure 6, tactile surfaces should be made so that the visually impaired can move forward safely. These surfaces should be in contrast with their surroundings and in a noticeable tone.

- There should be no elements, such as overhanging branches, thorny plants, or signboards, which are below the head recovery distance affecting (less than 220 cm height) the walking area on the sidewalk area.

- Ramps should be built to ensure transition and continuity between pavements. Ramps should be at a suitable slope with sufficient width to ensure safety and continuity so that all pedestrians, including persons with reduced mobility, can move freely.

- There should be no obstacles on the pavement so that all pedestrians, including those with limited mobility, can use the pavements safely and comfortably. All reinforcements that may create horizontal and vertical obstacles should be located in the pedestrian safety strip on the pavement.

- The width of the walking area on the sidewalk should be at least 150 cm so that all pedestrians, including those with limited mobility, can move freely. Minimum safety strip, walking area, and property strip widths on the sidewalk vary according to the pedestrian density.

5.3. Parking Areas

- Parking spaces equal to 5% of the total number of parking lots should be arranged for disabled users [69].

- Markings should be made on the floor and on the vertically positioned plate in the parking spaces arranged for disabled users.

- Since the parking lot to be arranged is a parking lot parallel to the road, the required distance should be left for maneuvering and movement on the side and back of the parking space arranged for disabled users. Including these distances, parking spaces designed disabled users for one vehicle should be 700 cm/400 cm.

- The connection point from the parking lot to the pavement must be made with a ramp.

- Other parking spaces should be arranged in suitable dimensions for vehicles (250 cm/500 cm). They should be divided by lines on the floor.

- Disabled parking area dimensions (parallel to the road): width: 400 cm, length: 700 cm

- Standard parking area dimensions (parallel to the road): width: 250 cm, length: 500 cm [69].

5.4. Pedestrian Crossings

- The junction of the sidewalk and the pedestrian crossing is damaged. This damage must be repaired. The level difference between them must be overcome with a ramp. The material used for this ramp must be non-slip. The ramp width should be equal to the width of the pedestrian crossing.

- A warning surface should be laid at the beginning and end of the pedestrian crossing to ensure the safety of the visually impaired. In addition, there should be a guide mark on the ground along the pedestrian crossing.

- In order to be perceived at night in the current situation, the flashing warning lamps located inside the pedestrian crossing should be moved before and after the pedestrian crossing. Thus, drivers can be aware of the pedestrian crossing when approaching. Furthermore, the risk of hitting this element in moments of carelessness of the users within the net usable area of the pedestrian crossing will be eliminated.

- At pedestrian crossings without light control, drivers must be warned with a pedestrian crossing sign at least 20 m before the pedestrian crossing.

- Pedestrian crossings should be well lit from above, this lighting should be separate and brighter in a distinguishable change from road lighting.

- Pedestrian crossings should be well marked with landmarks.

- Pedestrian crossings on vehicle roads and intersections should not be cut with curbstones. Three-way inclined ramps should be built to the pedestrian path as wide as the width of the pedestrian crossing up to the vehicle road level. The ramp (slope 8%) should not overflow into the carriageway.

- In order to ensure the safe passage of visually impaired pedestrians, guide tracks and warning surfaces should be created in the surface texture of the level pedestrian crossings. The minimum width of the pedestrian crossing must be 300 cm.

5.5. Urban Furniture and Equipment

- Urban furniture must be located within the safety strip and/or property strip specified on the pavement. They should not be positioned in the walking area.

- They should be in sizes suitable for everyone, including wheelchair users, short individuals, children, or they should be designed in different sizes and/or features to offer options to the user.

- Information signs and/or digital devices (such as parking area payment points) should be supported with the Braille alphabet, audio warning systems, and/or visual content, taking into account visually impaired and illiterate individuals.

- Lighting elements should have features to illuminate both the pavement and the vehicle road along the street.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yıldırım, S.; Asilsoy, B.; Özden, Ö. Urban Resident Views about Open Green Spaces: A Study in Güzelyurt (Morphou), Cyprus. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 9, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, M. United Nations Population Fund: State of World Population 2007: Unleashing the Potential of Urban Growth; UNFPA: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Debnath, A.K.; Chin, H.C.; Haque, M.M.; Yuen, B. A methodological framework for benchmarking smart transport cities. Cities 2014, 37, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asilsoy, B.; Oktay, D. Exploring environmental behaviour as the major determinant of ecological citizenship. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 39, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozarisoy, B.; Altan, H. Developing an evidence-based energy-policy framework to assess robust energy-performance evaluation and certification schemes in the South-eastern Mediterranean countries. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2021, 64, 65–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boström, M. A missing pillar? Challenges in theorizing and practicing social sustainability: Introduction to the special issue. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2012, 8, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavik, T.; Keitsch, M.M. Exploring relationships between universal design and social sustainable develop-ment: Some methodological aspects to the debate on the sciences of sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossett, A.; Mirza, M.; Barnds, A.K.; Feidt, D. Beyond access: A case study on the intersection between accessibility, sustainability, and universal design. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2009, 4, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinna, F.; Garau, C.; Maltinti, F.; Coni, M. Beyond Architectural Barriers: Building a Bridge Between Disability and Universal Design. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications, Cagliari, Italy, 1–4 July 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 706–721. [Google Scholar]

- Lid, I.M. Universal design and disability: An interdisciplinary perspective. Disabil. Rehabil. 2014, 36, 1344–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinfeld, E.; Maisel, J. What Is Universal Design? 2012. Available online: http://idea.ap.buffalo.edu/about/universal-design/ (accessed on 29 November 2020).

- Carmona, M.; Tiesdell, S.; Heath, T.; Oc, T. Public Places Urban Spaces, the Dimensions of Urban Design, 2nd ed.; Architectural Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lotfata, A.; Ataöv, A. Urban streets and urban social sustainability: A case study on Bagdat street in Kadikoy, Istanbul. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 1735–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenghi, A. Universal Design in Sustainable Urban Planning. In Green Planning for Cities and Communities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 119–138. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, C.W. Urban open space in the 21st century. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2002, 60, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell: Oxford, UK; Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Conteh, F.M.; Oktay, D. Measuring liveability by exploring urban qualities of kissy street, Freetown, Sierra Leone. Open House Int. 2016, 41, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Disability. In WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data; World Health Organization (WHO): Valletta, Malta, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, S. Design for the Disabled; RIBA Publications: London, UK, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Mace, R. Universal Design: Barrier Free Environments for Everyone. Des. West 1985, 33, 147–152. [Google Scholar]

- Sınmaz, S. Engelsiz Kent Tasarımı Üzerine Bir Yöntem Önerisi. In Proceedings of the 2th International Architecture and Design Congress, Çanakkale, Turkey, 11–12 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Persson, H.; Åhman, H.; Yngling, A.A.; Gulliksen, J. Universal design, inclusive design, accessible design, design for all: Different concepts—One goal? On the concept of accessibility—Historical, methodological and philo-sophical aspects. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2015, 14, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mace, L.R.; Hardie, J.G.; Place, J.P. Accessible Environments: Toward Universal Design; Barrier Free Environments: Raleigh, NC, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Preiser, W.; Korydon, S. Unıversal Desıgn Handbook; Mcgraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ostroff, E. Universal design: An evolving paradigm. In Universal Design Handbook; MacGraw Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; Volume 2, pp. 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Mace, R.L. A Perspective on Universal Design. In Proceedings of the Designing for the 21st Century: An International Conference on Universal Design, New York, NY, USA, 19 June 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Null, R. Commentary on universal design. Hous. Soc. 2003, 30, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisel, J.L.; Ranahan, M. Beyond Accessibility to Universal Design. 2017. Available online: https://www.wbdg.org/design-objectives/accessible/beyond-accessibility-universal-design (accessed on 29 November 2020).

- Yiing, C.F.; Yaacob, N.M.; Hussein, H. Achieving sustainable development: Accessibility of green buildings in Malaysia. Procedia–Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 101, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imrie, R. Universalism, universal design and equitable access to the built environment. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 34, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Center for Universal Design. A Guide to Evaluating the Universal Design Performance of Products. N.C. State University. 2003. Available online: https://projects.ncsu.edu/ncsu/design/cud/pubs_p/docs/UDPMD.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2012).

- Ahmed, M.E.K.; Ergenoğlu, A.S. An Assessment of Street Design with Universal Design Principles: Case in Aswan/As-Souq. Megaron 2016, 11, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Harsritanto, B.I. Urban environment development based on universal design principles. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2018; Volume 31, p. 09010. [Google Scholar]

- Erlandson, R.; Psenka, C. Building Knowledge into the Environment of Urban Public Space: Universal Design for Intelligent Infrastructure. J. Urban Technol. 2014, 21, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, W.H. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. In Common Ground? Readings and Reflections on Public Space; Orum, A.M., Neal, Z.P., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Du, M.; Zhang, X. Urban greening: A new paradox of economic or social sustainability? Land Use Policy 2020, 92, 104487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratiwi, A.R.; Zhao, S.; Mi, X. Quantifying the relationship between visitor satisfaction and perceived accessibility to pedestrian spaces on festival days. Front. Archit. Res. 2015, 4, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, S.L.; Boarnet, M.G.; Ewing, R.; Killingsworth, R.E. How the built environment affects physical activity: Views from urban planning. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 23, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, F.; Cambra, P.; Gonçalves, A.B. Measuring walkability for distinct pedestrian groups with a participatory assessment method: A case study in Lisbon. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 157, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, A. What is a walkable place? The walkability debate in urban design. Urban Des. Int. 2015, 20, 274–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litman, T.A. Economic Value of Walkability; Victoria Transport Policy Institute: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- De Certeau, M. The Practice of Everyday Life; University of Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- De Certeau, M.; Giard, L.; Mayol, P. The Practice of Everyday Life: Living and Cooking; University of Minnesota Press: South Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1990; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, N.; Cerin, E.; Leslie, E.; Coffee, N.; Frank, L.D.; Bauman, A.E.; Sallis, J.F. Neighborhood walkability and the walking behavior of Australian adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007, 33, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, J.; Ujang, N. Comfort of walking in the city center of Kuala Lumpur. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 170, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauws, W.; De Roo, G. Adaptive planning: Generating conditions for urban adaptability. Lessons from Dutch organic development strategies. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2016, 43, 1052–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandieh, R.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Zandieh, M. Adaptability of Public Spaces and Mental Health Inequalities during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Urban Des. Ment. Health 2020, 6, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, E. An integrative theory of urban design. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2000, 66, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizenberg, E.; Jabareen, Y. Social sustainability: A new conceptual framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcraft, S.; Bacon, N.; Caistor-Arendar, L.; Hackett, T. Design for Social Sustainability: A Framework for Creating Thriving New Communities; Young Foundation: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Chan, E.H.W.; Xu, Y. Sustainable Development and the Rehabilitation of a Historic UrbanDistrict—Social Sustainability in the Case of Tianzifang in Shanghai: Sustainable Development, Social, Rehabilitation Urban Historic Districts, Shanghai. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 22, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littig, B.; Grießler, E. Social sustainability: A catchword between political pragmatism and social theory. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polese, M.; Stren, R. The Social Sustainability of Cities: Diversity and the Management of Change; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada; Buffalo, NY, USA; London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, J.; Legun, K.; Campbell, H.; Carolan, M. Social sustainability indicators as performance. Geoforum 2019, 103, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N. Are Good-Quality Environments Socially Cohesive? Measuring Quality and Cohesion in Urban Neighbourhoods. Town Plan. Rev. 2009, 80, 315–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierson, J.H. Tackling Social Exclusion: Promoting Social Justice in Social Work; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, E.; Daoud, S.; Alrabaiah, H.; Badawi, R. Exploring undergraduate students’ attitudes towards emergency online learning during COVID-19: A case from the UAE. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 119, 105699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, H. Sustainable Communities: The Potential for Eco-Neighbourhoods; Earthscan: Oxfordshire, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bramley, G.; Dempsey, N.; Power, S.; Brown, C.; Watkins, D. Social sustainability and urban form: Evidence from five British cities. Environ. Plan. A 2009, 41, 2125–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthill, M. Strengthening the ‘social’ in sustainable development: Developing a conceptual framework for social sustainability in a rapid urban growth region in Australia. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.; Brown, C. The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, D. Cyprus: The South and the North. In Urban Issues and Urban Policies in the New EU Countries; Ashgate Publishing Ltd.: Farnham, UK, 2005; pp. 205–231. [Google Scholar]

- Erengin, P. Lefkoşa İlçesi’nin (KKTC) Yönetsel Coğrafya Bakımından Analizi. In Proceedings of the TÜCAUM 30 Yıl Uluslararası Coğrafya Sempozyumu International Geography Symposium on the 30th Anniversary of TUCAUM, Ankara, Turkey, 3–6 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Asilsoy, B.; Oktay, D. Measuring the potential for ecological citizenship among residents in Famagusta, North Cyprus. Open House Int. 2016, 41, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, D. An analysis and review of the divided city of Nicosia, Cyprus, and new perspectives. Geography 2007, 92, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozarisoy, B.; Altan, H. Adoption of energy design strategies for retrofitting mass housing estates in Northern Cyprus. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TSI. 2021. Available online: https://intweb.tse.org.tr/Yetki/Login/Login.aspx?Durum=TR (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- TS 12576; Urban RoadsStructural Preventive and Sign Design Criteria on Accessibility in Sidewalks and Pedestrian Crossings. Turkish Standards Institute: Ankara, Turkey, 2012.

- TS9111; The Requirements of Accessibility in Buildings for People with Disabilities and Mobility Constraints. Turkish Standards Institute: Ankara, Turkey, 2011.

- Ostroff, E.; Preiser, W. Universal Design Handbook; MacGraw Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

| Principle | Description | Design Details |

|---|---|---|

| Equitable use | The design is useful and marketable to individuals with diverse abilities. It aims to find solutions that are fair to everyone and are offered for equal use to everyone. |

|

| Flexibility in use | The design accommodates a wide range of individual preferences and abilities. This principle is about allowing users to select a suitable alternative for them. |

|

| Simple and intuitive use | Use of the design is easy to understand, regardless of the user’s experience, knowledge, language skills, or current concentration level. It ensures that the designer makes the design understandable to all. This principle is providing simplicity in design, reducing unnecessary complexity, and providing information in a consistent manner. |

|

| Perceptible information | The design communicates necessary information effectively to the user, regardless of ambient conditions or the user’s sensory abilities. |

|

| Tolerance for error | The design minimizes hazards and the adverse consequences of accidental or unintended actions. In other words, designs should be designed to minimize errors and accidents that may arise from user behavior. |

|

| Low physical effort | The design can be used efficiently and comfortably and with minimum fatigue. |

|

| Size and space for approach and use | Principle of appropriate size and space is provided for approach, reach, manipulation, and use, regardless of user’s body size, posture, or mobility. |

|

| Physical Indicators | Non-Physical Indicators |

|---|---|

| *Sustainable Urban Forms Compactness Density Sustainable transportation Mixed land uses Ecological design *Sustainable Urban Design Parameters Accessibility Connectivity Walkability Safety Adaptability Legibility Comfort | *Equity *Security *Poverty *Human Rights *Social Justice *Quality of Life Sense of place Identity and culture Social capital Social cohesion |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duman, Ü.; Asilsoy, B. Developing an Evidence-Based Framework of Universal Design in the Context of Sustainable Urban Planning in Northern Nicosia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13377. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013377

Duman Ü, Asilsoy B. Developing an Evidence-Based Framework of Universal Design in the Context of Sustainable Urban Planning in Northern Nicosia. Sustainability. 2022; 14(20):13377. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013377

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuman, Ümran, and Buket Asilsoy. 2022. "Developing an Evidence-Based Framework of Universal Design in the Context of Sustainable Urban Planning in Northern Nicosia" Sustainability 14, no. 20: 13377. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013377

APA StyleDuman, Ü., & Asilsoy, B. (2022). Developing an Evidence-Based Framework of Universal Design in the Context of Sustainable Urban Planning in Northern Nicosia. Sustainability, 14(20), 13377. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013377