Assessing the Health and Environmental Benefits of a New Zealand Diet Optimised for Health and Climate Protection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Optimising a Healthy, Sustainable Diet

- ‘All nutrients scenario’: All macronutrients and micronutrients with NZ or international nutrient recommendations (RDI or other) used as constraints: protein, polyunsaturated fat, fibre, calcium, iron, zinc, selenium, phosphorus, potassium, vitamin C, folate, niacin, riboflavin, thiamine, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, vitamin A, vitamin D, vitamin E, iodine, sodium, total fat, saturated fat and total sugars (N = 24)

- Micronutrients scenario: calcium, iron, zinc, selenium, phosphorus, potassium, vitamin C, folate, niacin, riboflavin, thiamine, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, vitamin A, vitamin D, vitamin E, iodine and sodium (N = 18)

- Fruit and vegetable intakes met or exceeded the age- and gender-specific guidelines (in grams/day (g/d))

- Red meat intake did not exceed the 500 g a week guideline

- Total grain intakes met the age- and gender-specific guidelines (the recommendations for this food group are in KJ rather than grams, e.g., Women over 70 years should have 3 serves with a serve being 500 KJ)

- Protein foods met the age and gender specific guidelines (in KJ rather than grams)

- Milk and milk products met the age and gender specific guidelines (in KJ rather than grams)

2.2. Translating the EAT-Lancet Diet for Modelling

2.3. DIET Multi-State Life-Table (MSLT) Modelling

3. Results

3.1. Optimisation Results

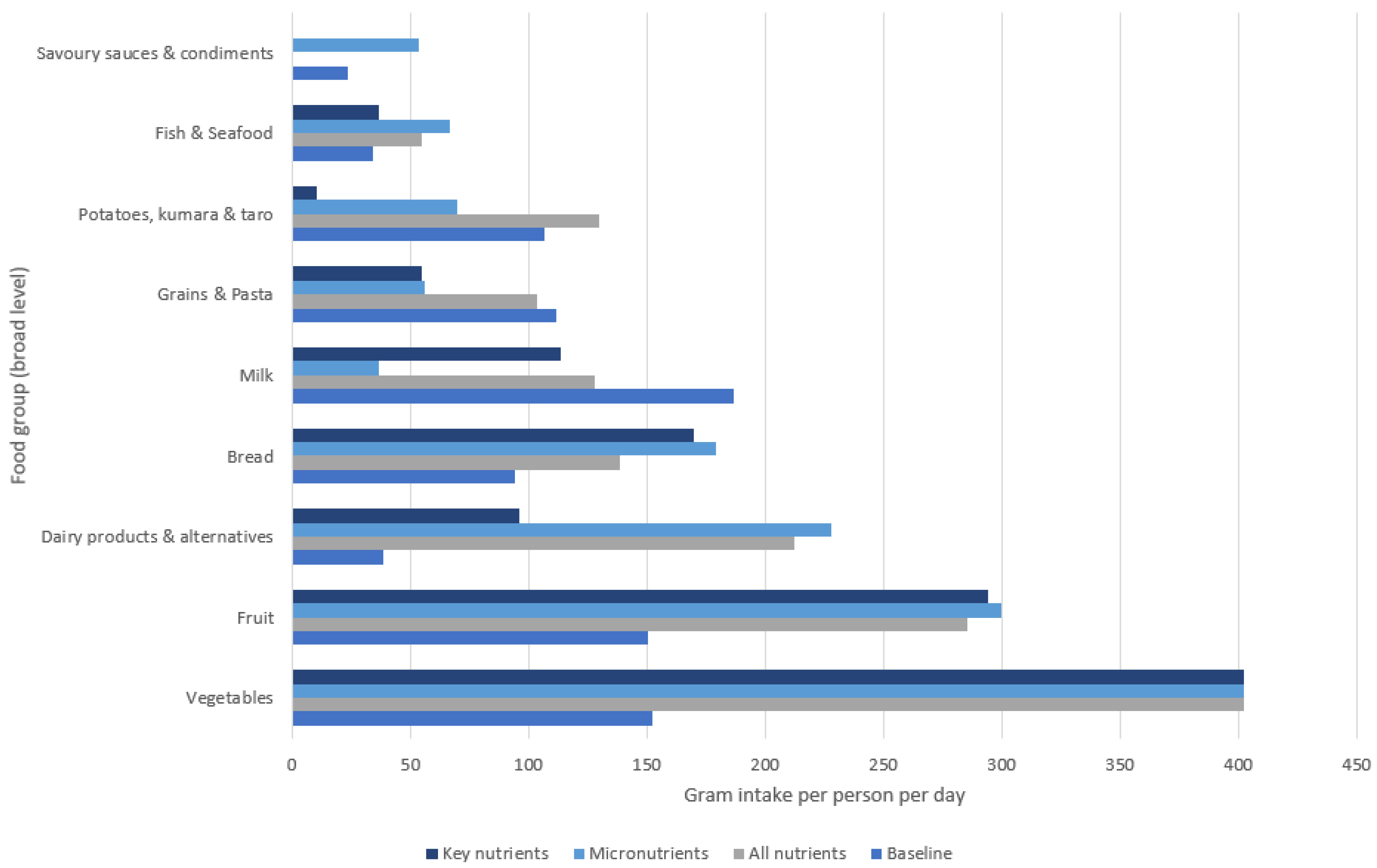

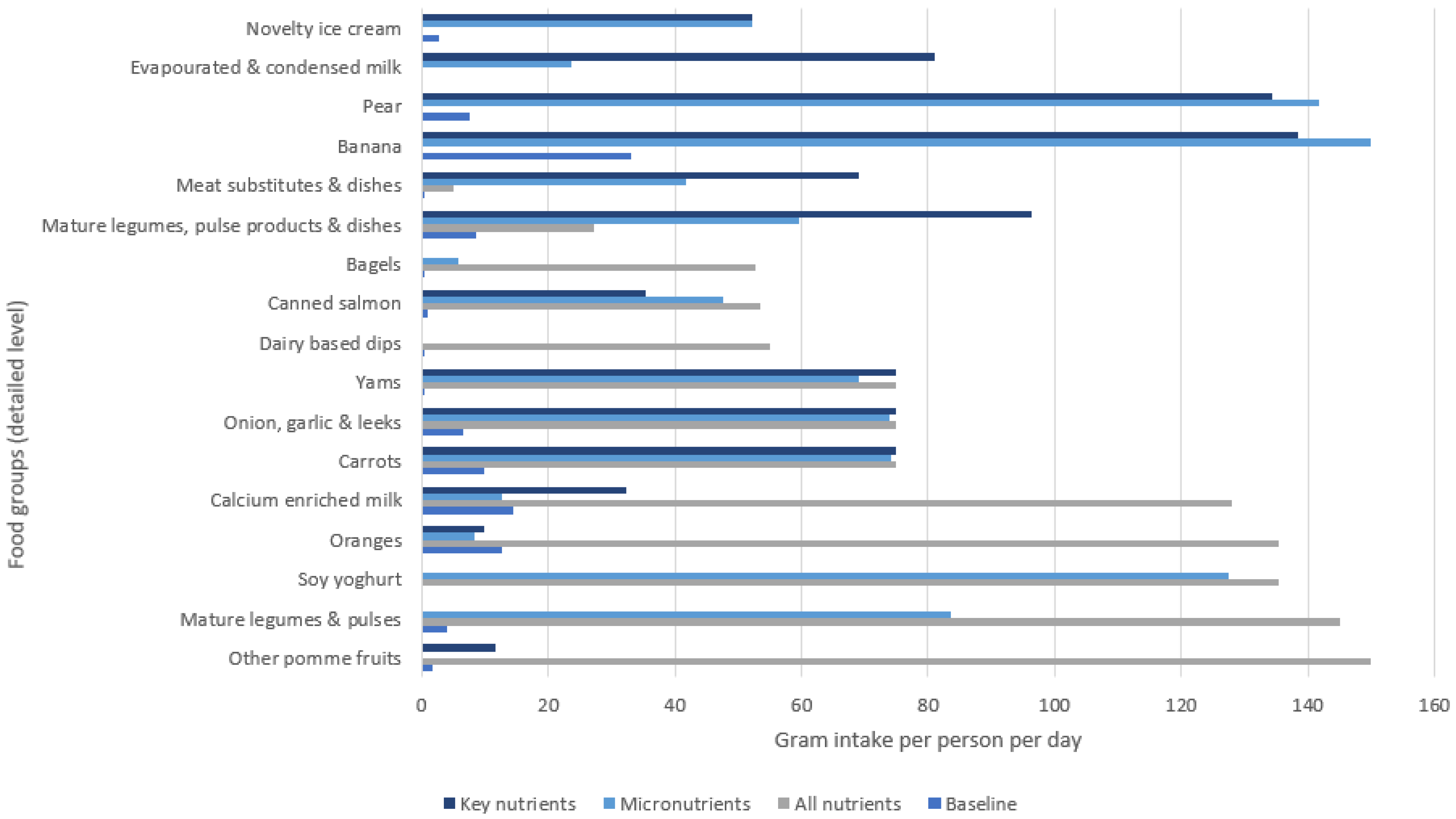

3.2. Selected Food Groups in Optimisation Scenarios

3.3. DIET MSLT Modelling Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Afshin, A.; Sur, P.J.; Fay, K.A.; Cornaby, L.; Ferrara, G.; Salama, J.S.; Mullany, E.C.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abebe, Z. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanogiannis, N.; Lawes, C.M.; Turley, M.; Tobias, M.; Vander Hoorn, S.; Mhurchu, C.N.; Rodgers, A. Nutrition and the burden of disease in New Zealand: 1997–2011. Public Health Nutr. 2005, 8, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- A Focus on Nutrition: Key Findings from the 2008/09 NZ Adult Nutrition Survey. Available online: https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/focus-nutrition-key-findings-2008-09-nz-adult-nutrition-survey (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Whitmee, S.; Haines, A.; Beyrer, C.; Boltz, F.; Capon, A.G.; de Souza Dias, B.F.; Ezeh, A.; Frumkin, H.; Gong, P.; Head, P. Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: Report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1973–2028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Corvalan, C.; Hales, S.; McMichael, A.J.; Butler, C.; McMichael, A. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Health Synthesis; World health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Swinburn, B.A.; Kraak, V.I.; Allender, S.; Atkins, V.J.; Baker, P.I.; Bogard, J.R.; Brinsden, H.; Calvillo, A.; De Schutter, O.; Devarajan, R. The global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change: The Lancet Commission report. Lancet 2019, 393, 791–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springmann, M.; Godfray, H.C.J.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. Analysis and valuation of the health and climate change cobenefits of dietary change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 4146–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.L.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, I.I.I.F.S.; Lambin, E.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J. Planetary boundaries: Exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, J.; Cleghorn, C.; Macmillan, A.; Mizdrak, A. Healthy and Climate-Friendly Eating Patterns in the New Zealand Context. Environ. Health Perspect. 2020, 128, 017007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N.; Cleghorn, C.L.; Cobiac, L.J.; Mizdrak, A.; Nghiem, N. Achieving Healthy and Sustainable Diets: A Review of the Results of Recent Mathematical Optimization Studies. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, S389–S403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, R.; Milner, J.; Dangour, A.D.; Haines, A.; Chalabi, Z.; Markandya, A.; Spadaro, J.; Wilkinson, P. The potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the UK through healthy and realistic dietary change. Clim. Chang. 2015, 129, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dooren, C.; Tyszler, M.; Kramer, G.F.; Aiking, H. Combining low price, low climate impact and high nutritional value in one shopping basket through diet optimization by linear programming. Sustainability 2015, 7, 12837–12855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieux, F.; Perignon, M.; Gazan, R.; Darmon, N. Dietary changes needed to improve diet sustainability: Are they similar across Europe? Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gephart, J.A.; Davis, K.F.; Emery, K.A.; Leach, A.M.; Galloway, J.N.; Pace, M.L. The environmental cost of subsistence: Optimizing diets to minimize footprints. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 553, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, M.A.; Springmann, M.; Hill, J.; Tilman, D. Multiple health and environmental impacts of foods. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 23357–23362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health: Data and Statistics, Nutrition Survey, 2008/09 Adult Nutrition Survey. 2011. Available online: http://www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/indexmh/dataandstatistics-survey-nutrition (accessed on 1 August 2011).

- Andersen, L.S.; Gaffney, O.; Lamb, W.; Hoff, H.; Wood, A. A Safe Operating Space for New Zealand/Aotearoa. Translating the Planetary Boundaries Framework; Ministry for the Environment: Wellington, New Zealand, 2020; Available online: https://www.stockholmresilience.org/download/18.66e0efc517643c2b810218e/1612341172295/Updated%20PBNZ-Report-Design-v6.0.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Wilson, N.; Nghiem, N.; Ni Mhurchu, C.; Eyles, H.; Baker, M.G.; Blakely, T. Foods and dietary patterns that are healthy, low-cost, and environmentally sustainable: A case study of optimization modeling for New Zealand. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, N.B.; Madsen, M.L.; Hansen, T.H.; Allin, K.H.; Hoppe, C.; Fagt, S.; Lausten, M.S.; Gøbel, R.J.; Vestergaard, H.; Hansen, T. Intake of macro-and micronutrients in Danish vegans. Nutr. J. 2015, 14, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seves, S.M.; Verkaik-Kloosterman, J.; Biesbroek, S.; Temme, E.H. Are more environmentally sustainable diets with less meat and dairy nutritionally adequate? Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 2050–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magkos, F.; Tetens, I.; Bügel, S.G.; Felby, C.; Schacht, S.R.; Hill, J.O.; Ravussin, E.; Astrup, A. A perspective on the transition to plant-based diets: A diet change may attenuate climate change, but can it also attenuate obesity and chronic disease risk? Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. Eating and Activity Guidelines for New Zealand Adults: Updated 2020; Ministry of Health: Wellington, New Zealand, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cleghorn, C.; Blakely, T.; Nghiem, N.; Mizdrak, A.; Wilson, N. Technical Report for BODE3 Intervention and DIET MSLT Models, Version 1. Burden of Disease Epidemiology, Equity and Cost-Effectiveness Programme; Technical Report no. 16; Department of Public Health UoO, Wellington, Ed.; Department of Public Health UoO: Wellington, New Zealand, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Forouzanfar, M.H.; Alexander, L.; Anderson, H.R.; Bachman, V.F.; Biryukov, S.; Brauer, M.; Burnett, R.; Casey, D.; Coates, M.M.; Cohen, A. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015, 386, 2287–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, J.A.; Vos, T.; Hogan, D.R.; Gagnon, M.; Naghavi, M.; Mokdad, A.; Begum, N.; Shah, R.; Karyana, M.; Kosen, S. Common values in assessing health outcomes from disease and injury: Disability weights measurement study for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013, 380, 2129–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvizhinadze, G.; Nghiem, N.; Atkinson, J.; Blakely, T. Cost Off-Sets Used in BODE3 Multistate Lifetable Models Burden of Disease Epidemiology, Equity and Cost-Effectiveness Programme (BODE3); Technical Report: Number 15; University of Otago: Wellington, New Zealand, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hoolohan, C.; Berners-Lee, M.; McKinstry-West, J.; Hewitt, C. Mitigating the greenhouse gas emissions embodied in food through realistic consumer choices. Energy Policy 2013, 63, 1065–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, M.; Blakely, T.; Kvizhinadze, G.; Harris, R. Why equal treatment is not always equitable: The impact of existing ethnic health inequalities in cost-effectiveness modeling. Popul. Health Metr. 2014, 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blakely, T.; Cleghorn, C.; Petrović-van der Deen, F.; Cobiac, L.J.; Mizdrak, A.; Mackenbach, J.P.; Woodward, A.; van Baal, P.; Wilson, N. Prospective impact of tobacco eradication and overweight and obesity eradication on future morbidity and health-adjusted life expectancy: Simulation study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2020, 74, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| GHG Emissions (% of Baseline) | Price (% of Baseline) | Energy Intake (% of Baseline) | Total Grams of Diet, Excluding Beverages Except Milk (% of Baseline) * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All nutrients scenario | ||||

| Total population ** | 1.83 (54%) | $12.82 (79%) | 8778 (100%) | 1548 (118%) |

| Māori males | 1.87 (42%) | $13.83 (70%) | 10,000 (90%) | 1640 (109%) |

| Māori females | 1.79 (62%) | $12.57 (88%) | 8542 (110%) | 1514 (132%) |

| non-Māori males | 1.85 (46%) | $13.13 (71%) | 9104 (90%) | 1580 (106%) |

| non-Māori females | 1.82 (63%) | $12.40 (87%) | 8292 (110%) | 1507 (128%) |

| Micronutrients scenario | ||||

| Total population ** | 1.66 (49%) | $16.42 (100%) | 9358 (106%) | 1480 (112%) |

| Māori males | 1.66 (37%) | $18.65 (94%) | 10,515 (95%) | 1594 (106%) |

| Māori females | 1.95 (67%) | $14.36 (100%) | 8542 (110%) | 1562 (136%) |

| non-Māori males | 1.65 (41%) | $18.58 (100%) | 10,406 (103%) | 1590 (106%) |

| non-Māori females | 1.62 (56%) | $14.32 (100%) | 8292 (110%) | 1338 (113%) |

| Key nutrients scenario | ||||

| Total population ** | 1.59 (47%) | $14.29 (87%) | 8704 (99%) | 1265 (96%) |

| Māori males | 1.60 (36%) | $16.02 (81%) | 10,000 (90%) | 1424 (95%) |

| Māori females | 1.95 (67%) | $11.36 (79%) | 7581 (98%) | 1283 (112%) |

| non-Māori males | 1.59 (39%) | $15.02 (81%) | 9108 (90%) | 1285 (86%) |

| non-Māori females | 1.53 (53%) | $13.81 (96%) | 8292 (110%) | 1215 (103%) |

| Optimised Sustainable NZ Diet (Percent of Baseline Intake) | EAT-Lancet Diet (Percent of Baseline Intake) | |

|---|---|---|

| ∆ Fruit (g/day) | 135.4 (90%) | 50.2 (33%) |

| ∆ Vegetables (g/day) | 250.1 (164%) | 266.8 (175%) |

| ∆ Red meat (g/day) | −53.1 (−100%) | −45.3 (−85%) |

| ∆ Processed meat (g/day) | −56.7 (−91%) | −60.8 (−97%) |

| ∆ SSB (g/day) | −109.3 (−100%) | −109.2 (−100%) |

| ∆ Nuts and seeds (g/day) | 8.4 (137%) | 43.9 (712%) |

| ∆ Sodium (mg/day) | −453.5 (−21%) | −611.6 (−29%) |

| ∆ PUFA (% of total energy) | 2.7 (53%) | 7.7 (150%) |

| Non-Māori | Māori | Māori | Ethnic Groups Combined | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Gains: QALYs | Health Gains: QALYs | Equity Analysis Health Gains: QALYs * | Health Gains: QALYs | Net Health System Cost Savings (2011 NZ$ Billion) | |

| Optimised sustainable NZ diet | |||||

| Sex groups combined ** | 1,057,000 (843,800 to 1,290,900) | 313,600 (260,000 to 372,500) | 428,900 (349,200 to 517,600) | 1,370,600 (1,107,600 to 1,664,000) | $19.7 (14.8 to 25.1) |

| Men | 621,500 | 167,500 | 228,600 | 789,000 | $11.9 |

| Women | 435,500 | 146,000 | 200,400 | 581,600 | $7.8 |

| Per capita *** | 283.3 (345.2) | 465.1 (600.7) | 636.2 (823.7) | 311.1 | $4473.8 |

| EAT-Lancet diet | |||||

| Sex groups combined ** | 1,035,200 (829,400 to 1,267,200) | 339,600 (279,700 to 406,600) | 462,000 (375,500 to 563,800) | 1,374,800 (1,110,000 to 1,676,000) | $20.5 (15.5 to 26.3) |

| Men | 609,200 | 198,500 | 268,700 | 807,800 | $12.6 |

| Women | 426,000 | 141,100 | 193,300 | 567,000 | $7.9 |

| Per capita *** | 277.5 (337.8) | 503.7 (650.3) | 685.3 (886.9) | 312.1 | $4649.7 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cleghorn, C.; Nghiem, N.; Ni Mhurchu, C. Assessing the Health and Environmental Benefits of a New Zealand Diet Optimised for Health and Climate Protection. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13900. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113900

Cleghorn C, Nghiem N, Ni Mhurchu C. Assessing the Health and Environmental Benefits of a New Zealand Diet Optimised for Health and Climate Protection. Sustainability. 2022; 14(21):13900. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113900

Chicago/Turabian StyleCleghorn, Christine, Nhung Nghiem, and Cliona Ni Mhurchu. 2022. "Assessing the Health and Environmental Benefits of a New Zealand Diet Optimised for Health and Climate Protection" Sustainability 14, no. 21: 13900. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113900

APA StyleCleghorn, C., Nghiem, N., & Ni Mhurchu, C. (2022). Assessing the Health and Environmental Benefits of a New Zealand Diet Optimised for Health and Climate Protection. Sustainability, 14(21), 13900. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113900