Abstract

Crime statistics indicate that the total number of annually reported crimes decreased steadily between 2008 and 2019 in South Africa. However, annually reported robberies have been steadily increasing over the same period. Additionally, South Africa remains plagued by high income inequality. This paper presents a system dynamics simulation model describing the relationships between education inequality, income inequality and robbery in South Africa. The model employs strain theory to project the effectiveness of interventions aimed at increasing South African education levels to decrease income inequality and thereby reduce robbery. The model explored robbery prevention interventions aimed at increasing South African education levels to reduce the current high level of income inequality. The results suggest that reducing robbery incidents through improved education levels will require a long time to become effective but will have long-lasting effects. Furthermore, the results indicate that combinations of interventions generate more substantial effects than the sum of effects produced by interventions applied in isolation.

1. Introduction

1.1. Crime in South Africa

In the South African context, robbery is defined as the theft of property by deliberately using violence or threats of violence to gain possession of property [1]. These offences are listed under robbery with aggravating circumstances in the annually released statistical reports of the South African Police Service (SAPS).

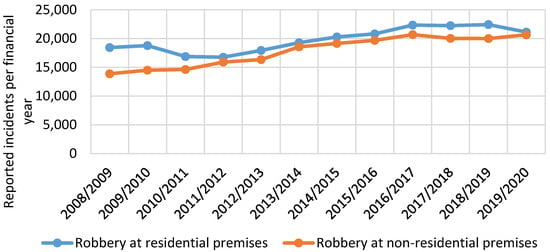

Figure 1 shows the trend of robberies at residential- and non-residential premises. Robbery at residential premises rose by 14.60% from 18,438 incidents during the 2008/2009 financial year to 21,130 incidents for 2019/2020. Robbery at non-residential premises increased by 48.73% from 13,885 to 20,651 incidents during the same period. This shows that, even though recorded crime incidents in South Africa have been decreasing, recorded incidents of robbery at residential- and non-residential premises have gradually increased. We conclude from this that although governmental strategies to reduce crime in South Africa may have helped to reduce some categories of crime, the strategies have not been effective for robbery in particular.

Figure 1.

Incidents of robbery at residential- and non-residential premises recorded in South Africa for the financial years 2008/2009 to 2018/2020 [2].

1.2. Income Inequality in South Africa

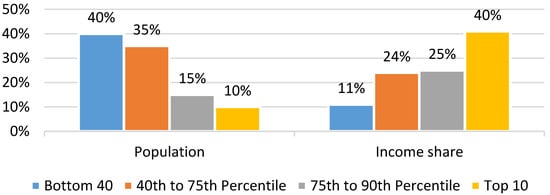

According to the World Development Indicators with 0.63, South Africa exhibited the highest Gini coefficient in 2018. From the Income and Expenditure Surveys for 2005/06 and 2010/11 and the Living Conditions Surveys for 2014/15, Sulla and Zikhali [3] calculated the income shares of the South African population during 2015, as can be seen in Figure 2. The figure compares the total annual income of a population group with its respective population size. The population groups have been ranked from the lowest-earning to the highest-earning according to the following percentile ranges: 0–40, 40–75, 75–90 and 90–100. As shown in the figure, 41% of the South African annual income has been earned by only 10% of the population, whilst 40% of the population with the lowest income earned only 11% of the total annual income in 2015. This shows the significant inequality present in South Africa’s income distribution.

Figure 2.

Income shares of the South African population in 2015 (Amended from [3]).

1.3. Education Inequality as a Cause of South African Income Inequality

Sulla and Zikhali [3] state that among various factors affecting inequality, education and labour market affiliation are primarily responsible for overall inequality in South Africa. Among other types of inequality, South Africa is marked by high wealth inequality. This arises from high income-inequality and inequality of opportunity for children [3].

In a study investigating higher education access and success of the 2008 National Senior Certificate (NSC) cohort, van Broekhuizen, van der Berg and Hofmeyr [4] show that learners from poorer schools were far less likely to access universities to pursue undergraduate diplomas and undergraduate degrees within six years of writing the 2008 NSC examinations.

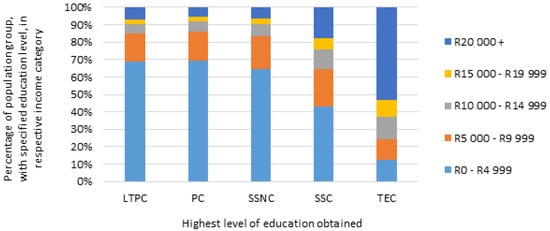

Access to and completion of higher education levels also considerably affects household income. Insight into this phenomenon may be gained from investigating the results of the General Household Surveys (GHS) conducted between 2009 and 2018 [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Figure 3 shows household incomes (household incomes were measured in South African Rands per month) according to the highest education level reached by the individual. The results from Figure 3 were derived by calculating the averages for the data available from GHS 2009 up to GHS 2018. The education levels considered are: less than primary school completed (LTPC), primary school completed (PC), secondary school not completed (SSNC), secondary school completed (SSC) and tertiary education completed (TEC) (tertiary education in this case only consists of diplomas with Grade 12/Standard 10, bachelor’s degrees, post-graduate diplomas and honours degrees). Figure 3 shows that about 53% of the population that has obtained tertiary education are living in households of the highest income group. On the other hand, 68.6, 69.1 and 64.6% of the population that have obtained LTPC, PC and SSNC, respectively, are living in households of the lowest income group. This suggests that the completion of tertiary education is a strong determinant of household income in South Africa.

Figure 3.

Averages of household income according to highest education level of the individual derived from data of the 2010–2018 General Household Surveys.

1.4. Linking Income Inequality and Crime in South Africa

Although the drivers of crime are far more complex and varied, the link between income inequality and crime has been much explored in the academic literature (discussed in more detail in Section 2). In an attempt to investigate the influence of local inequality on violent- and property crime in South Africa, [15] found evidence of the causal relationship between inequality and property crime in the South African context.

By drawing on extant criminology theories (discussed in Section 2), this study attempts to investigate core drivers of robbery in the context of South African education- and income inequality. The core objective is to develop a policy-testing tool using system dynamics (SD) modelling to explore the possible outcomes that education interventions may have on crime. System Dynamics modelling is a computer-based methodology especially suitable for modelling high-level system dynamics of complex behaviours. The method uses tools such as causal loop diagrams to conceptualize feedback loops and stock and flow diagrams to implement them as a system of differential equations (See Section 3 for a detailed explanation of the method).

Through the SD methodology, it is also possible to model the longer-term effects of policy interventions and highlight appropriate time frames over which results take effect.

The objectives pursued in this article are:

- Formulate a system dynamics model that captures the fundamental factors relating to the link between income inequality and crime in South Africa;

- Test the model according to the model testing guidelines discussed by Sterman [16] to determine the credibility of the model concerning the problem addressed;

- Develop and compare different strategies addressing the identified core drivers to reduce the number of annual robbery incidents;

- Recommend future research for model improvement.

The following section unpacks the core theories used in this modelling study (Section 2), followed by the methodology (Section 3). Next, the formulation of the model is discussed in Section 4 with the model tests policy formulation, followed by the limitations and future work (Section 5) and conclusions (Section 6).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Drivers of Crime in South Africa

It is not possible to give a single explanation for South Africa’s high levels of crime and increasing levels of violent crime, but rather a number of explanations exist that may help to understand the driving forces behind them [17,18]. These explanations should consider, among other causes, the link between the country’s violent history, the impact of the increasing availability of firearms, the growth in organized crime and the result of a poorly functioning criminal justice system [18].

Additionally, crime may not be prevented only through law enforcement and the criminal justice system. Ideally, criminal acts should be prevented even before the criminal justice system needs to intervene. Therefore, crime and violence may be prevented in various ways through social crime prevention approaches that address social and economic challenges. Such approaches, however, require commitment and an understanding of the complex dynamics that function in a specific society [19]. Therefore, explaining the causes of crime and violence in South Africa is not a simple task [17].

In a report prepared for the South African Minister of Safety and Security by the CSVR, it is stated that ‘the core of the problem of violent crime in South Africa is a culture of violence and criminality, associated with a strong emphasis on the use of weapons’ [20]. The report states that several specific factors may be seen as contributing to sustaining this culture. Some (additional factors discussed in the report include social exclusion, the proliferation of firearms, organized criminal economies and the legacy of war in Southern Africa [17]) of these factors, as discussed in the report, are listed in Table 1 and supported with more recent references.

Table 1.

Some of the factors described as sustaining the culture of violence and criminality in South Africa [20].

Taking into account the multiple factors mentioned in Table 1, it becomes apparent that the problem of high and increasing levels of violent crime in South Africa is complex and multifaceted. To achieve focus on this complexity, the scope of this study was the drivers of aggravated robbery forming part of violent crime within the context of South African inequality. The relationship between inequality and crime, concerning criminological theory and empirical evidence, will be further discussed in the following sub-sections.

2.2. Theories Advocating the Link between Inequality and Crime

The causal relationship between inequality and crime is advocated by three main ecological theories of crime, namely: Becker’s [34] economic theory of crime, Shaw and McKay’s [35] social disorganization theory and Merton’s [36] strain theory [37]. Rather than substitutes, these three theories should be seen as complimentary, where each theory focuses on different aspects of the link between inequality and crime. Strain theory focuses on various stresses that may induce crime. Social disorganization theory examines informal social controls (informal social control refers to the ability of local neighbourhoods to oversee the behaviour of their residents and the proficiency of neighbourhoods to socialize their residents normally [38] of crime [37]. Economic theory of crime primarily examines the rational decision-making process that potential offenders face when weighing up the possible gains of offending against the consequences (imposed by the legal system) of being caught [39].

In a collaborative effort, Akers, Sellers and Jennings [40] composed an overview of various criminological theories. In their chapter on anomie (anomie refers to a state of normlessness in modern society as a situation that advances higher rates of behaviour violating social norms [32,33] and strain theories (the words ‘anomie’ and ‘strain’ are frequently used interchangeably when making reference to Merton’s [36] theory and later theories shaped by his view [4]), they introduce anomie/strain theory as having much in common with social disorganization theory. Akers, Sellers and Jennings [40] describe a social system, such as a community or society, to be socially organized and integrated if a common consensus exists on its values and norms, a firm bond is found among its members and communal interaction occurs in a peaceful manner. Conversely, the social system is said to be disorganized or anomic when its social cohesion or integration is distorted, social control is deteriorating or when its members are in disagreement. Social disorganization- and anomie theories both advocate that disintegration of cohesion within a social system leads to higher rates of crime [40].

Social disorganization and anomie theories differ according to the proposed mechanism by which disorder increases criminal incidents. Social disorganization theory suggests that rapid change and disorder debilitate a social system’s ability to restrain the behaviour of its members. This allows for the growth of criminal values that contrast conventional values, thereby increasing the likelihood of crime within the social system. Anomie/strain theory proposes that social disintegration specifically debilitates the moral hold that norms and laws have on the members of the social system. In this view, crime is likely to occur only if the disintegration is combined with blocked or limited access to economic objectives. Such an anomic structural condition generates a strain on system members. Criminal behaviour then arises as one of the ways that people adapt to this type of strain [40].

Anomie/strain theory strongly relies on the work of one of the founders of sociology, Émile Durkheim [41,42] referred to a state of normlessness in modern society as a situation that advances higher rates of behaviour violating social norms. This state he called anomie. Merton [36] applied Durkheim’s approach to modern industrial societies [40]. This was the beginning of anomie/strain theory, which was further developed by various other authors such as Agnew [43], Rosenfeld and Messner [44] among others [40]. Research that looks for empirical evidence for these theories finds some support for their hypotheses, but the relationships are usually not strong [40]. On the other hand, research investigating the link between inequality and crime, which may be derived from the above description of anomie/strain theories, has found more significant support. Supporting arguments for the causal link between inequality and crime will be discussed next.

2.3. Empirical Evidence of the Relationship between Inequality and Crime

In a longstanding study, Danziger used an economic model to investigate the influence of income inequality (Danziger [45] used a Gini coefficient of family incomes as the measure of inequality) on robbery using crime rates for 1970, as reported by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) for 222 Standard Metropolitan Statistical Areas (SMSAs) in the United States of America. The regression results showed that income inequality positively correlated with robbery rates in the 222 SMSAs [45]. In a similar study, Jacobs [46] found similar results. Blau and Blau [47] tested the hypothesis stating that a specific type of inequality is likely to create conflict, manifesting as criminal violence incidents. Their results suggest that economic inequality, among other inequalities, does promote criminal violence [9]. Hsieh and Pugh [48] conducted a meta-analysis of 34 aggregate data studies that reported on violent crime, poverty and income inequality. The meta-analysis showed that the studies generated 76 zero-order correlation coefficients for all measures of violent crime with either income inequality or poverty.

Furthermore, 74 of the coefficients were positive, and nearly 80% of these were of at least moderate strength (>0.25). The study concluded that both poverty and income inequality are associated with violent crime. Kelly [37] investigated the relationship between inequality and crime using crime data taken from the 1991 FBI Uniform Crime reports. Here, robbery falls under violent crime. The results show that inequality has a strong and robust impact on violent crime for the given data set.

Lederman, Loayza and Menéndez [49] conducted a cross-country study for about 39 countries with national data from 1980–1994. Their study verified that income inequality (income inequality was measured by the Gini coefficient) and growth rate (growth rate was measured as per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rate) are robust determinants of violent crime incidents for the examined datasets. Fajnzylber, Lederman and Loayza [50] conducted a similar study to investigate the robustness and causality of the link between income inequality and violent crime, such as homicide and robbery, across countries. Their results indicate that incidents of considered violent crime and income inequality are positively correlated, thereby reflecting the causal effect of inequality on crime rates.

Most of the previously-mentioned studies have been conducted with a focus on the United States of America. In their attempt to investigate the influence of local inequality on violent- and property crime in South Africa, Demombynes and Özler [15] examined, among others, the approaches in some of the literature above and identified various limitations. Their study addressed these limitations and applied their approach to South Africa. Their results agree with sociological theories, which argue that inequality leads to crime in general, and economic theories that associate inequality with property crime. This provides evidence that the causal relationship between inequality and property crime exists in the South African context.

3. Methodology

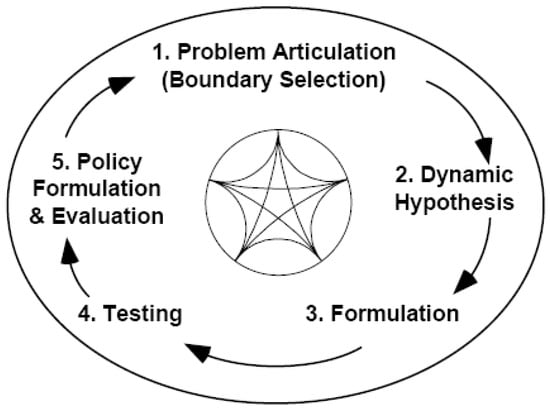

System dynamics is a method to aid in describing and understanding complex systems [16]. The methodology has been effectively used to model public policy problems [51,52]. SD methodology allows the researcher to test the consequences of changes to the system structure or inputs and explore desirable system changes [53]. Policy development can take place from there. As described by Sterman and shown in Figure 4 and further discussed below, SD modelling is an iterative process. The SD process, as laid out in this article, consists of five steps (1) Problem articulation, (2) Dynamic hypothesis, (3) Formulation of the stock and flow diagram, (4) Testing, (5) Policy formulation and evaluation [16].

Figure 4.

Steps of the SD methodology.

3.1. Step 1: Problem Articulation

The foremost step of the modelling process is articulating the problem behaviour of the system. This first step enables the modeller to also state a clear purpose for the model. The purpose acts as the “logical knife” of what to include in the model and also to set the model boundaries. This is summarized in Section 4.1.

3.2. Step 2: Develop a Dynamic Hypothesis

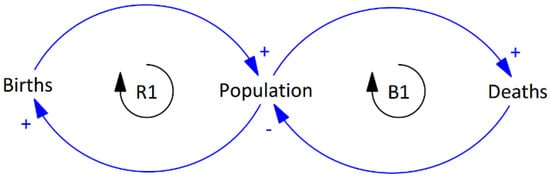

The dynamic hypothesis is the formulation of a theory of how the system developed a problem behaviour. The dynamics of the problem assist the modeller in describing feedback loops through causal loop diagrams (CLDs)—shown in Section 4.2. The procedure for creating the basic model of a population is shown below as an example to explain the modelling methodology briefly. Figure 5 shows a CLD of a population growth dynamic. This example shows variables (births, population, deaths) and arrows linking these variables (with polarities indicating the direction of the relationship). These connections, in turn, create feedback loops. For example, the notation R1 shows a positive reinforcing loop while B1 shows a balancing loop (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Causal loop diagram of a population.

3.3. Step 3: Model Formulation

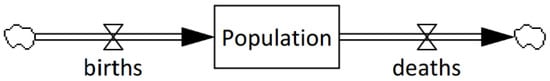

Stock and flow diagrams are developed during model formulation to represent the CLDs mathematically (a system of differential equations). The computational modelling of the system was done using Vensim software in Figure 6. The basic Stock and Flow diagram is shown in Section 4.3.

Figure 6.

Stock and flow diagram of a population.

3.4. Step 4: Testing

Testing the model comprises much more than simply replicating historical data. Tests were conducted on the model to ensure dimensional consistency, the sensitivity of the model in terms of policy recommendations and uncertainty in assumptions. These tests are vital tools for identifying flaws in the model and are described in Section 4.4.

3.5. Step 5: Policy Formulation and Evaluation

After the researchers developed confidence in the model’s structure and behaviour, the “what-if” testing of various policy options could be executed on the model. This is discussed in more detail in Section 4.5.

4. Model Development

4.1. Problem Articulation

As mentioned in the introductory chapter, South Africa continues to experience an increasing trend in robbery at residential- and non-residential premises, despite ongoing crime prevention policies. In this study, we build on criminology theories to explain the causes for violent crime in South Africa. The investigation revealed that a culture of crime and violence is the core driver of South African violent crime. Furthermore, it was discovered that even though crime is a hugely complex issue and has many drivers, inequality, among others, is considered one of the factors sustaining this culture. As the study’s scope aligns with the South African 2030 NDP, this study focuses on violent property crime in the context of South African inequality. We now deductively unpack our dynamic hypothesis in the following section.

4.2. Develop a Dynamic Hypothesis

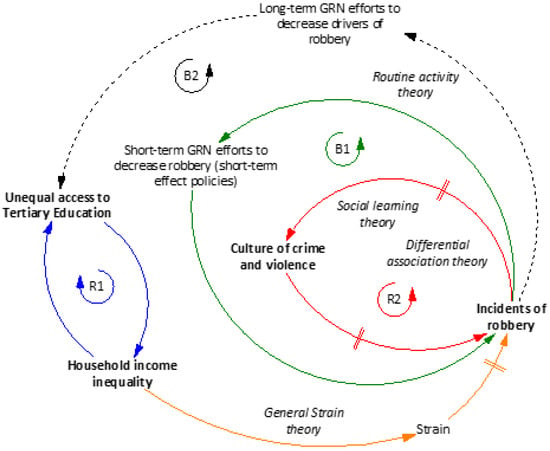

This study’s dynamic hypothesis is a working theory that attempts to explain the increasing trend of robbery in South Africa in the context of South African education- and income inequality. Figure 7 is a simplified representation of the dynamic hypothesis for this study, presented in the form of a high-level causal loop diagram, and indicates some of the underlying forces that have been found to drive robbery in South Africa in the context of income- and education inequality.

Figure 7.

Dynamic hypothesis for drivers of robbery in the context of South African income- and education inequality.

The first reinforcing loop (R1) represents the relationship between unequal access to tertiary education (as in Section 4, tertiary education in this case only consists of diplomas with Grade 12/Standard 10, bachelor’s degrees, post-graduate diplomas and honours degrees) and household income inequality. Here, an increase in household income inequality is postulated to lead to higher inequality of access to tertiary education. A higher inequality of access to tertiary education, in turn, also increases household income inequality. According to strain theory, an increase in household income inequality also causes an increase in strain. Then, according to strain theory, an increase in this strain leads to an increased chance of robbery [3]. From this point, the second reinforcing loop (R2) emerges.

R2 is mainly motivated by the arguments of social learning theory and differential association theory. For these theories, exposure to certain norms and values means that they are learned by individuals exposed to them [54,55]. Therefore, an increase in robbery incidents causes a higher exposure to norms and values that view robbery as a legitimate means of reducing the strain caused by household income inequality. It follows that individuals learn more of these norms in society. An increase in these norms leads to a rise in a culture of crime and violence, which is a sustaining factor. This, then again, leads to more incidents of robbery. The first balancing loop (B1) also emerges from this point.

B1 represents the short-term efforts of the government to reduce the number of robberies. These focus on a quick reduction of the chances of possible robbery incidents that already motivated potential offenders would commit. Here, the force that motivates people is not addressed but rather the factors needed for a crime to occur. According to routine activity theory, a criminal act minimally requires three elements. These elements are (1) a potential offender, (2) a suitable target and (3) the absence of guardians that might prevent the act from occurring successfully [56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69]. In B1, the government aims to eliminate elements two and three to reduce incidents of crime. The final balancing loop (B2) also emerges from incidents of robbery.

B2 represents long-term efforts of the government to reduce the core drivers that motivate people to commit robbery. According to routine activity theory, as defined by Cohen and Felson [56], this strategy addresses the first element required for a criminal act to occur: a potential offender. Addressing the factors that motivate people to commit robbery may be done in various ways. In this study, however, the focus is on South African income- and education inequality. Therefore, the motivation to commit robbery will be addressed by targeting South African income- and education inequality.

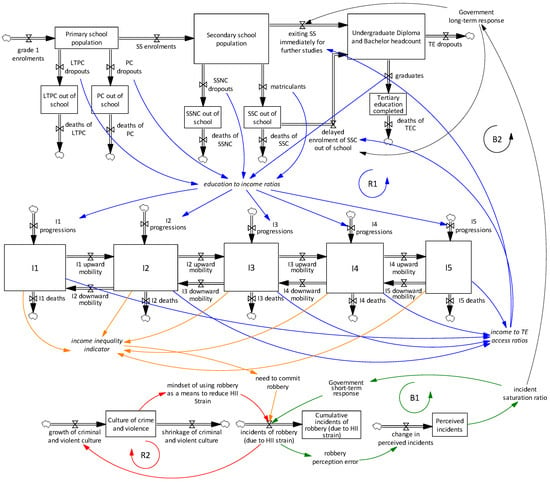

4.3. Model Formulation

This section presents a high-level overview of the formal stock and flow model in Figure 8. Firstly, a simplified overview of the entire model is provided. Then, the model is described in more detail according to the three sub-structures that make up the whole model. Figure 8 is a simplified representation of the simulation model’s entire stock and flow structure (the detailed stock and flow diagram explanations are available in the full thesis at this link: https://scholar.sun.ac.za/handle/10019.1/110013?show=full accessed on 11 October 2022).

Figure 8.

Simplified stock and flow structure of entire simulation model.

The first sub-structure, which may be referred to as the education structure, represents populations of South Africans according to their highest level of education (See the Appendix A, Table A1 for the model boundary chart). Education levels range from ‘less than primary complete’ (LTPC) to ‘tertiary education (as in the dynamic hypothesis, tertiary education in this case only consists of diplomas with Grade 12/standard 10, bachelor’s degrees, post-graduate diplomas and honours degrees. This constraint was implemented mainly due to information of NSC cohort progressions to higher education institutions being available only for the given degrees and diploma) completed’ (TEC). Education levels that are lower than LTPC, such as pre-schooling and no education at all, were not accounted for. The structure accounts for population groups that are currently enrolled at primary-, secondary- and tertiary education institutions. The structure also accounts for population groups that have either completed a specific education level or dropped out before completing a specific education level and discontinued any further learning.

The second sub-structure, which may be referred to as the income structure, represents populations of South Africans according to their average monthly household incomes and is a co-flow of the education structure (See the Appendix A, Table A2 for the model boundary chart). The income levels of the five population stocks correspond to the income categories shown in Figure 8, where I1 represents the population with the lowest average monthly household income and I5 the population with the highest average monthly household income. The five inflows, labelled as ‘progressions’, are influenced by five outflows from the education structure according to ratios similar to those in Figure 3.

People may flow between income category stocks according to each stock’s respective upward- and downward mobility rate. The structure accounts for population deaths through outflows at each income category stock. The income category stocks of the income structure influence two flows from the education structure and represent access to tertiary education through access ratios. This, therefore, creates the first reinforcing loop (R1) describing the relationship between tertiary education access inequality and household income inequality.

The third sub-structure, which may be referred to as the crime structure, represents incidents of robbery due to household income inequality and the culture of crime and violence associated with it (See the Appendix A, Table A3 for the model boundary chart). The income structure influences the crime structure through an income inequality indicator that, in turn, affects the need to commit robbery, which then influences the flow of incidents of robbery due to household income inequality.

From this point, the second reinforcing loop (R2) emerges. Incidents of robbery due to household income inequality strain influence the flow representing the growth of the culture of crime and violence. The stock representing the culture of crime and violence currently present in society affects the mindsets of individuals regarding the use of robbery as a legitimate means to reduce the strain imposed on them due to household income inequality. This, then returns to influence the flow representing robbery incidents due to household income inequality and completes the second reinforcing loop (R2).

From this point, the first balancing loop (B1) also emerges. In this loop, the government’s short-term response to the current number of robbery incidents is delayed by a structure that distinguishes between the actual number- and the perceived number of robbery incidents. The government’s response is then influenced by the perceived number of robbery incidents and affects the actual number of robbery incidents. This response is introduced as the degree to which the number of opportunities to commit robbery is reduced by the government interventions, thereby closing the first balancing loop (B1).

The second balancing loop (B2) emerges from the incident saturation ratio. B2 represents long-term effect interventions introduced by the government to target drivers of robbery. In this study, these drivers are economic- and educational inequality. In the model, this is defined as increased access to tertiary education for those who have obtained the NSC.

4.4. Model Testing

The simulation model was subjected to several tests to determine the level of confidence that may be attached to the model’s results. These tests included (1) boundary adequacy tests, (2) structure assessment, (3) dimensional consistency, (4) parameter assessment, (5) extreme conditions, (6) integration errors, (7) behaviour reproduction and (8) sensitivity analysis. Results from three of these tests will be briefly discussed here.

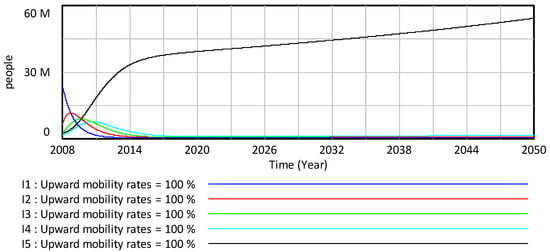

Various extreme conditions were tested to determine whether the model behaves realistically even when subjected to such unlikely conditions. The tests revealed that the model does behave realistically under extreme conditions. An example of this may be seen in Figure 9. For this extreme-conditions test, all upward mobility rates of the income sub-model increased to 100% since 2008. It was expected that the population stocks I1 up to I4 would decrease sequentially as each stock reached a new equilibrium and finally levelled out. Population stock I5 should initially increase dramatically as the other stocks reach their new equilibrium conditions. After the system reaches a new equilibrium, the I5 stock should gradually increase. The test revealed that the model behaved as expected, as may be observed in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Simulation results of stocks I1–I5 for extreme condition test.

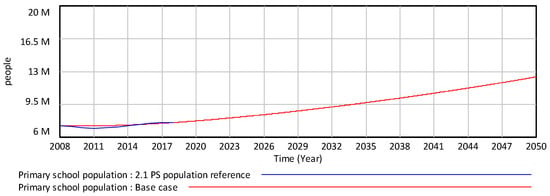

Additionally, the authors evaluated the model with the behaviour reproduction test. Sterman [69] provides quantitative and qualitative methods to perform this test. For this study, only qualitative methods of behaviour reproduction testing were applied. The simple qualitative behaviour reproduction test used for this study involved visually comparing the results of predicted variables of the simulation to real-world data. The test revealed that the model’s results generally follow the data trends.

An example of this may be observed in Figure 10, which shows the real-world data (the real-world data for the primary school population was obtained from annual reports, called ‘School Realities’, published by the Department for Basic Education in South Africa [57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67] of the primary school population in blue and the simulation results in red. From the graph, it can be observed that the simulation results generally fit the real-world data. The simulation model has been calibrated to achieve this fit.

Figure 10.

Behaviour reproduction test for primary school population stock of education sub-model.

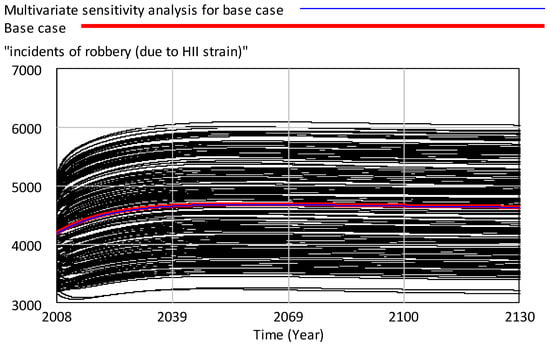

Furthermore, the researchers performed sensitivity analysis. We tested for numerical- and behaviour-mode sensitivity. This was done to test the robustness of the conclusions drawn from the simulation model against the uncertainty of the assumptions made. Monte Carlo simulation was used to identify 12 highly uncertain constants that were highly influential regarding the results generated by the model’s four key output parameters. The four key output parameters of the model are called “Ratio of Tertiary education completed”, “Income Inequality Indicator (III)”, “Incidents of robbery (due to household inequality strain)” and “Culture of crime and violence”. Multivariate sensitivity analysis was then performed with these constants. This was done by randomly varying them between the minimum and maximum values that correspond to 75 and 125% of the estimated constant (base) values, as may be seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameters and corresponding values used for multivariate sensitivity analysis.

The sensitivity analysis revealed that all four key output parameters of the model exhibit numerical sensitivity, whereas only two of these initially exhibit slight behaviour mode sensitivity. An example of this may be seen in Figure 11, showing the results of the multivariate sensitivity analysis for the robbery incidents variable. Figure 11 indicates that this variable exhibits considerable numerical sensitivity. Further on, the simulation runs below the base case run, shown in Figure 11, suggest that this variable initially exhibits slight behaviour mode sensitivity.

Figure 11.

Individual simulation runs of the ‘incidents of robbery (due to HII strain)’ variable produced during multivariate sensitivity analysis under base case conditions.

From these tests, the authors concluded that the simulation model might be considered adequate regarding the model’s purpose. Further parameter estimation may be performed to decrease the model’s degree of numerical- and behaviour mode sensitivity. The following section summarizes the main results generated by the simulation model.

4.5. Policy Formulation and Evaluation

Six major levers for interventions were identified throughout the development of the model. These interventions are listed and briefly described in Table 3. As per the focus of our study, all interventions tested focus on the education system of South Africa. The first intervention represents a 50% reduction in secondary school dropouts. The following five interventions aim to increase access to tertiary education for pupils who have successfully completed Grade 12. The model was constructed in such a manner that tertiary education access rates for Grade 12 pupils from different household income categories may be adjusted independently. The second intervention, therefore, represents an increase in access to tertiary education for Grade 12 pupils living in households with an average monthly income between R0 and R4999. The third, fourth-, fifth- and sixth interventions are similar to the second intervention, but the income categories of Grade 12 pupils differ for each of these interventions, as described in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of identified intervention points.

To test the impact of the six defined interventions, eleven scenarios were designed (listed in Table 4). Interventions one to six were abbreviated as I1 to I6. Scenarios 1 to 6 represent the six interventions applied in isolation. Scenarios 7 to 11 represent various combinations of the six interventions.

Table 4.

Scenarios developed from the six identified interventions.

From the results (See Table 5), the following policy implications regarding violent property crime prevention, are suggested.

Table 5.

Summary of results generated from scenarios.

The initial increase of robberies caused by interventions due to initial increases in income inequality may be subdued with short-term approaches that aim at reducing the opportunity of robbery rather than the motivation for robbery. These interventions may include measures such as increased police visibility and the implementation of neighbourhood patrol organizations.

Scenario 1, representing a 50% reduction in the secondary school dropout rate, exhibited the most significant reduction of income inequality and, therefore, the most considerable reduction of robbery among scenarios testing interventions in isolation. When tested in combination with other interventions, the secondary school dropout reduction also generated the most considerable synergistic effects. Therefore, the results suggest that, amongst the tested interventions, reducing secondary school dropout is the most effective intervention explored. For this reason, secondary school dropout may be considered a considerable long-term intervention point in the fight against violent property crime.

Branson, Hofmeyr and Lam (2014) used the second wave (the National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS) has been repeated every two or three years since 2007. Each interview round is referred to as a “wave”. The second wave refers to the interview round conducted in 2010 [68] of the National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS) to identify determinants of school dropout in South Africa. Their results indicate that school dropout is significantly larger in secondary school than in primary school [68]. In addition, the authors found that survey respondents most often stated pregnancy, insufficient funds and work-related responsibilities as the main reasons for dropping out of school before completing Grade 12 [68]. This indicates that the application of intervention 1 would require a broad range of strategies to address the various reasons for dropping out of secondary school.

Interventions 2 to 6 increased tertiary education access rates for Grade 12 pupils, from five household income categories, to 50%. The results show progressively lower (albeit small) reductions in robbery for each intervention that targets a higher income category. This behaviour pattern seems to occur for two reasons. Firstly, the relative population sizes of Grade 12 pupils from the five household income categories mean that increased access for larger populations generates more tertiary education enrolments. Secondly, the different percentage increases of tertiary education access rates applied to Grade 12 pupils from different household income categories mean that higher tertiary education access rate increases, from the current rate, mean more tertiary education enrolments. In other words, the results indicate that the more Grade 12 pupils access tertiary education, the more income inequality is reduced, which generates a more significant reduction in robbery incidents over time. This, of course, will also be dependent on sufficient capacity increases in the tertiary education systems.

In their study on tertiary education access and success, [4] used a nationally representative dataset on Grade 12 learners and university students to determine three major bottlenecks preventing the increase in university access in South Africa (from the supply-side). The first bottleneck is the weak progression of Grade 1 learners towards Grade 12 [4]. Official enrolment figures indicate that only about 60% of learners who start primary school progress to Grade 12 to write the final National Senior Certificate (NSC) examinations [69]. Secondly, only a few learners who manage to write the NSC examinations achieve a pass mark that makes them eligible for undergraduate studies. Less than 38 and 32% of Grade 12 learners who passed the NSC examinations, respectively, achieved diploma and bachelor’s passes. Thirdly, only a few of those learners who achieve diploma and bachelor passes actually proceed to enrol at university. Only 20% of the 2008 NSC cohort (the 2008 NSC cohort refers to all learners who wrote the 2008 National Senior Certificate (NSC) examinations) advanced to enrol at public universities between 2009 and 2014 [4].

The results shown in Table 5 align with the findings of van Broekhuizen, van der Berg and Hofmeyr [4]. Table 5 shows that a combination of all interventions in scenario 11 (entailing a lower secondary school dropout rate with higher tertiary education access for Grade 12 learners from all income categories) generated the most significant increase in tertiary education completion. This then produced the most significant decrease in income inequality and, therefore, the greatest reduction in robbery incidents. However, as stated by van Broekhuizen, van der Berg and Hofmeyr, many questions regarding tertiary education access in South Africa remain unanswered. For example, it is still unclear why so many Grade 12 learners who appear to be eligible for university studies do not enter public universities. It is also unclear to what extent home backgrounds and financial constraints determine whether learners can proceed to university [4]. This implies that further research is needed to answer these questions.

Overall, the simulation results suggest that a reduction of robbery incidents through the decrease in income inequality, brought about by increased education levels among South Africans, will require a long time to take effect. The models had to run over a 100-year time horizon to show significant results in the predicted outputs due to the generational pressures placed on children through poverty and inequalities. However, the findings from this study do suggest that such interventions also generate long-lasting effects, which would require a long time to reverse. Additionally, the results indicate that combinations of interventions generate more substantial effects than the sum of effects for interventions applied in isolation. Therefore, the interventions discussed may help produce long-lasting reductions in income inequality that eventually lead to sustained reductions in robbery. Due to the synergistic effects exhibited by the results, it seems that the discussed interventions would generate more desirable results when applied in combination. This aligns with the argument of Kruger et al. [19] which maintains that the complexity of crime and violence requires various factors to be considered to implement integrated and sustained interventions that receive a continuous commitment from a range of role players.

5. Limitations and Future Work

As is the case for any simulation study, this study exhibits several limitations. This section describes some core limitations of the model and briefly describes how these limitations may be addressed to improve and expand the model in the future.

The structure of the income sub-model only allows for a crude estimation of income inequality. The model only accounts for five income categories, in R5000 intervals, with the highest income category allowing for an infinite range. The model structure is restricted to five income categories to keep the model simple. The highest income category already begins at R20,000 due to the limited upper-income ranges generated by the General Household Surveys (GHS) conducted between 2009 and 2017. In the future, more and smaller ranges of income categories may be incorporated to generate a more accurate representation of income inequality.

The model focused explicitly on violent property crime. However, future work may also include exploring the expansion of this model to other areas of crime. The general idea that inequality leads to crime suggests that this may hold promise.

The model is represented at a national level due to inadequate access to data at lower aggregation levels. A lower level of aggregation at provincial or municipal levels would allow more accurate representations of the real system. The development of the model at a national level does, however, indicate the system’s behaviour as a whole without having to spend more resources on modelling all provinces or municipal areas.

Sensitivity analysis revealed that the model contains several highly uncertain parameters, which are also significantly influential regarding the model’s four key output parameters. Therefore, the model exhibits considerable numerical sensitivity. Additionally, it was found that the model does exhibit slight behaviour mode sensitivity at the beginning of the simulation period. This, therefore, calls for further parameter estimation. Additionally, policy sensitivity was not tested for. This may also be performed in the future to better understand the range of uncertainties that exist regarding results generated by the tested interventions.

6. Conclusions

This article presented the problem of an increasing trend of annual robberies in South Africa between 2008 and 2019. Various literature was presented, discussing factors that influence South African violent crime. The arguments from this literature suggest that one of the factors influencing South African violent crime is income inequality. This income inequality is suggested to exist in close relationship with education inequality. Furthermore, criminological theory and empirical evidence advocating the relationship between inequality and crime were presented for various countries, including South Africa.

Aligned with arguments of criminological theories and evidence provided by empirical studies, this article presented a system dynamics simulation model describing relationships between education inequality, income inequality and robbery in South Africa. The results section presented robbery prevention interventions aimed at increasing South African education levels to reduce the current high level of income inequality.

From the generated results, it may be concluded that sustained reductions in secondary school dropouts and sustained increases in tertiary education access may require considerable time before South African robbery incidents are reduced substantially through these interventions. However, the results suggest that these interventions may produce long-lasting reductions in income inequality and, therefore, also long-lasting reductions of robbery in South Africa. Furthermore, due to the synergistic effects exhibited by the results, it seems that the discussed interventions would generate more desirable results when applied in combination.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.A. and S.G.; methodology, F.A. and S.G.; software, F.A.; validation, F.A. and S.G.; formal analysis, F.A.; investigation, F.A.; resources, S.G.; data curation, F.A.; writing—original draft preparation, F.A. and S.G.; writing—review and editing, F.A. and S.G.; visualization, F.A.; supervision, S.G.; project administration, S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the Faculty of Engineering at Stellenbosch University (protocol code 10190 and approved on 24 July 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Model boundary chart for education sub-model.

Table A1.

Model boundary chart for education sub-model.

| Endogenous | Exogenous | Excluded |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 enrolments, Primary school population Primary school pupils dropping out before completing Grade 7 Population, not enrolled in any educational institution, whose highest- and final level of education is less than Grade 7 Deaths of people forming part of populations that are not enrolled in an educational institution Primary school pupils dropping out of the school system after completing Grade 7 Population, not enrolled in any educational institution, whose highest- and final level of education is Grade 7 Secondary school enrolments Secondary school population Secondary school pupils dropping out before completing Grade 12 Population, not enrolled in any educational institution, whose highest- and final level of education is less than Grade 12 Enrolments for AET and FET after either dropping out of- or completing secondary school The flow representing matriculants moving to an intermediate state population where some will continue to tertiary education, while most will not Population, not enrolled in any educational institution, whose highest- and partially final level of education is Grade 12 Population, not enrolled in any educational institution, whose highest- and partially final level of education is Grade 12 Matriculants immediately enrolling at tertiary education institutions Matriculants delaying enrolment at tertiary education institutions for up to 5 years Population enrolled at tertiary education institutions for undergraduate degrees and diplomas of NQF levels 6, 7 and 8 Students dropping out of undergraduate degrees and diplomas of NQF levels 6, 7 and 8 Graduations of students studying undergraduate degrees and diplomas of NQF levels 6, 7 and 8 Population, not enrolled in any educational institution, whose highest- and final level of education is an undergraduate degree or diploma of NQF level 6, 7 or 8 Births in South Africa Deaths in South Africa South African population Tertiary education access rates for matriculants from households with different incomes | Percentage of total South African population entering Grade 1 annually Normal dropout rates of primary school pupils Percentage of primary school population that is in grade 7 Transition rate from primary school to secondary school Dropout rate of secondary school pupils AET and FET enrolment rates Percentage of secondary school population that is in grade 12 Percentage of Grade 12 population that does not immediately continue to tertiary education Dropout rate for students enrolled at tertiary education institutions for undergraduate degrees and diplomas of NQF levels 6, 7 and 8 Graduation rate of students studying undergraduate degrees and diplomas of NQF levels 6, 7 and 8 Crude South African birth rate Crude South African death rate Percentages governing the delay of enrolment for matriculants from households with differing incomes, which do access tertiary education within five years of matriculation | Tertiary education other than undergraduate degrees and diplomas equivalent to NQF levels 6, 7 and 8 People without any level of education Quality of education offered at educational institutions The effect of early childhood development on dropout and educational attainment |

Table A2.

Model boundary chart for income sub-model.

Table A2.

Model boundary chart for income sub-model.

| Endogenous | Exogenous | Excluded |

|---|---|---|

| Flows representing progressions into the various household income categories Populations representing people not attending any educational institution according to five income categories Upward- and downward mobility of people between the five income category populations Deaths of people in the five income category populations | Ratios determining the distribution of progressions of people with various education levels into different income category populations Upward- and downward mobility rates of flows between the five income category populations South African crude death rate | Availability of jobs affecting people’s earning capability Employment- and unemployment levels Influence of populations with AET and FET qualifications on household income levels Influence of other tertiary qualifications, besides those named, on income levels |

Table A3.

Model boundary chart for robbery sub-model.

Table A3.

Model boundary chart for robbery sub-model.

| Endogenous | Exogenous | Excluded |

|---|---|---|

| Income Inequality Indicator (III) The need to commit robbery due to household income inequality Incidents of robbery due to household income inequality Level of criminal and violent culture present in the South African society Growth and decay of South African culture of crime and violence Mindset of people regarding the use of robbery as a means of reducing the strain imposed by household income inequality Difference between actual incidents of robbery and perceived number of robbery incidents Adjustment between perceived and actual incidents of robbery Perceived number of robbery incidents Ratio of actual- over possible incidents of robbery Short-term government response to number of robberies occurring Long-term government response to number of robberies occurring | Maximum strain attainable due to income inequality Relation of the Income Inequality Indicator (III) to strain due to household income inequality Factor determining the sustaining effect that incidents of robbery have on the culture of crime and violence Maximum culture of crime and violence attainable in the societyTime required for present culture of crime and violence to fade from society Number of opportunities to commit robbery in a year Time interval between robbery incident reports Time needed to adjust robbery incident perception error Time available for robbery incidents to occur Relation of number of robberies to short-term government response Relation of number of robberies to long-term government response | Other types of crime influenced by strain due to household income inequality Impact of other types of strain on the occurrence of robbery Other factors influencing the culture of crime and violence in the society Additional factors influencing an individual’s mindset regarding the act of committing robbery (e.g., rational choice theory) Reporting error influencing the authorities’ perceptions regarding robbery incidents |

References

- Burchell, J.M. Principles of Criminal Law, 3rd ed.; Juta: Lansdowne, South Africa, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- South African Police Service. 2017/2018 Annual Crime Report; South African Police Service: Pretoria, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sulla, V.; Zikhali, P. Overcoming Poverty and Inequality in South Africa: An Assessment of Drivers, Constraints and Opportunities; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- van Broekhuizen, H.; van der Berg, S.; Hofmeyr, H. From Grade 12 into, and through, university: Higher education access and success for the 2008 national NSC cohort. In Post-School Education and the Labour Market in South Africa; Rogan, M., Ed.; HSRC Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 2018; pp. 79–99. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa. South Africa—General Household Survey 2010; Statistics South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa.

- Statistics South Africa. South Africa—General Household Survey 2011. Available online: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0318/P03182010.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Statistics South Africa. South Africa—General Household Survey 2012. Available online: https://www.datafirst.uct.ac.za/dataportal/index.php/catalog/445 (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Statistics South Africa. South Africa—General Household Survey 2013. Available online: https://www.datafirst.uct.ac.za/dataportal/index.php/catalog/486 (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Statistics South Africa. South Africa—General Household Survey 2014. Available online: https://www.datafirst.uct.ac.za/dataportal/index.php/catalog/526 (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Statistics South Africa. South Africa—General Household Survey 2015. Available online: https://www.datafirst.uct.ac.za/dataportal/index.php/catalog/715 (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Statistics South Africa. South Africa—General Household Survey 2016. Available online: https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/2879 (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Statistics South Africa. General Household Survey 2017 Dataset; DataFirst: Pretoria, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa. South Africa—General Household Survey 2018. Available online: https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/3512 (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Statistics South Africa. General Household Survey 2018 Dataset; DataFirst: Pretoria, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demombynes, G.; Özler, B. Crime and local inequality in South Africa. J. Dev. Econ. 2005, 76, 265–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterman, J. Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modelling for a Complex World, 1st ed.; McGraw-Hill, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- CSVR. The Violent Nature of Crime in South Africa; CSVR: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schönteich, M.; Louw, A. Crime in South Africa: A Country and Cities Profile; Institute for Security Studies: Pretoria, South Africa, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kruger, T.; Lancaster, L.; Landman, K.; Liebermann, S.; Louw, A.; Robertshaw, R. Making South Africa Safe: A Manual for Community-based Crime Prevention; CSIR: Delhi, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- CSVR. Tackling Armed Violence: Key Findings and Recommendations of the Study on the Violent Nature of Crime in South Africa; CSVR: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, G.; Vermaak, C. Economic inequality as a source of interpersonal violence: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa and South Africa. South African J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2015, 18, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Enamorado, T.; López-Calva, L.F.; Rodríguez-Castelán, C.; Winkler, H. Income inequality and violent crime: Evidence from Mexico’s drug war. J. Dev. Econ. 2016, 120, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekoya, A.F. Income Inequality and Violent Crime in Nigeria: A Panel Corrected Standard Error Approach. Ibadan J. Peace Dev. 2019, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Anser, M.K.; Yousaf, Z.; Nassani, A.A.; Alotaibi, S.M.; Kabbani, A.; Zaman, K. Dynamic linkages between poverty, inequality, crime, and social expenditures in a panel of 16 countries: Two-step GMM estimates. J. Econ. Struct. 2020, 9, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufrancos, H.G.; Power, M.; Pickett, K.E.; Richard, W. Income Inequality and Crime: A Review and Explanation of the Time–series Evidence. Sociol. Criminol. 2013, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheteni, P.; Mah, G.; Yohane, K.Y. Drug-related crime and poverty in South Africa. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2018, 6, 1534528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazorodze, B.T. Youth unemployment and murder crimes in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2020, 8, 1799480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrinder, N. Untangling the Determinants of Crime in South Africa. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, 2013. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Andresen, M.A. Unemployment, business cycles, crime, and the Canadian provinces. J. Crim. Justice 2013, 41, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewkes, R.; Sikweyiya, Y.; Morrell, R.; Dunkle, K. Gender Inequitable Masculinity and Sexual Entitlement in Rape Perpetration South Africa: Findings of a Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, T.; Myers, B.J.; Louw, J.; Lombard, C.; Flisher, A.J. The relationship between substance use and delinquency among high-school students in Cape Town, South Africa. J. Adolesc. 2013, 36, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mncube, V.; Madikizela-Madiya, N. Gangsterism as a cause of violence in South African schools: The case of six provinces. J. Sociol. Soc. Anthropol. 2014, 5, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaliyo, J.-C. Townships as Crime ‘Hot-Spot’ Areas in Cape Town: Perceived Root Causes of Crime in Site B, Khayelitsha. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 596–603. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G.S. Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach. J. Polit. Econ. 1968, 76, 169–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, C.R.; McKay, H.D. Juvenile Delinquency and Urban Areas; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, R.K. Social Structure and Anomie. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1938, 3, 672–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M. Inequality and Crime. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2000, 82, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bursik, R.J. Social disorganization and theories of crime and delinquency: Problems and prospects. Criminology 1988, 26, 519–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garoupa, N. Economic Theory of Criminal Behavior. In Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Akers, R.L.; Sellers, C.S.; Jennings, W.G. Criminological Theories: Introduction, Evaluation, and Application, 7th ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, E. Le Suicide: Étude de Sociologie On Suicide; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 1897. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, E. Suicide: A Study in Sociology; Free Press: Glencoe, IL, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew, R. Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology 1992, 30, 47–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, R.; Messner, S.F. Crime and the American Dream, 1st ed.; Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Danziger, S. Explaining Urban Crime Rates. Criminology 1976, 14, 291–296. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, D. Inequality and Economic Crime. Sociol. Soc. Res. 1981, 66, 12–28. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, J.R.; Blau, P.M. The cost of inequality: Metropolitan structure and violent crime. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1982, 47, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.-C.; Pugh, M.D. Poverty, income inequality, and violent crime: A meta-analysis of recent aggregate data studies. Crim. Justice Rev. 1993, 18, 182–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederman, D.; Loayza, N.; Menéndez, A.M. Violent Crime: Does Social Capital Matter? Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 2002, 50, 509–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajnzylber, P.; Lederman, D.; Loayza, N. Inequality and Violent Crime. J. Law Econ. 2002, 45, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, J.W. Industrial Dynamics; M.I.T. Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaffarzadegan, N.; Lyneis, J.; Richardson, G.P. How small system dynamics models can help the public policy process. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2011, 27, 22–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruyt, E. Small System Dynamics Models for Big Issues: Triple Jump towards Real-World Complexity. TU Delft Library: Delft, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, T. Social Learning Theory. In Oxford Bibliographies Online; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bosiakoh, T.A. Differential Association Theory. In Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L.E.; Felson, M. Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: A Routine Activity Approach. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1979, 44, 588–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Basic Education South Africa. School Realities 2008; Department for Basic Education South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2008. Available online: https://www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=KQB1AFSaSOk%3D&tabid=462&portalid=0&mid=1327&forcedownload=true (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Department for Basic Education South Africa. School Realities 2009; Department for Basic Education South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2009. Available online: https://www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=pcHIu5M4Xeo%3D&tabid=462&portalid=0&mid=1327&forcedownload=true (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Department for Basic Education South Africa. School Realities 2010; Department for Basic Education South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2010. Available online: https://www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=UdGRjcHLNik%3D&tabid=462&portalid=0&mid=1327&forcedownload=true (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Department for Basic Education South Africa. School Realities 2011; Department for Basic Education South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2011. Available online: https://www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=X16-OOIfxAk%3D&tabid=462&portalid=0&mid=1327&forcedownload=true (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Department for Basic Education South Africa. School Realities 2012; Department for Basic Education South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2012. Available online: https://www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=XnCbuP9in7k%3D&tabid=462&portalid=0&mid=1327&forcedownload=true (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Department for Basic Education South Africa. School Realities 2013; Department for Basic Education South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2013. Available online: https://www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=SqEviUGpJng%3D&tabid=462&portalid=0&mid=1327&forcedownload=true (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Department for Basic Education South Africa. School Realities 2014; Department for Basic Education South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2014. Available online: https://www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=qWrI-U3L4WY%3D&tabid=462&portalid=0&mid=1327&forcedownload=true (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Department for Basic Education South Africa. School Realities 2015; Department for Basic Education South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2015. Available online: https://www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=qGIz6zeGMhE%3D&tabid=462&portalid=0&mid=1327&forcedownload=true (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Department for Basic Education South Africa. School Realities 2016; Department for Basic Education South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2016. Available online: https://www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=ZdTAcZEVeMY%3D&tabid=462&portalid=0&mid=1326&forcedownload=true (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- Department for Basic Education South Africa. School Realities 2017; Department for Basic Education South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2017. Available online: https://www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=KVwfNwZG728%3D&tabid=462&portalid=0&mid=1327&forcedownload=true (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- Department for Basic Education South Africa. School Realities 2018; Department for Basic Education South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2018. Available online: https://www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=Wggp_-rXzAc%3D&tabid=462&portalid=0&mid=1326&forcedownload=true (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit. What Is NIDS? Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit: Cape Town, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- van Wyk, C. An overview of key data sets in education in South Africa. South African J. Child. Educ. 2015, 5, 146–170. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).