1. Introduction

With the growth of fierce competition in the global economy, it is essential for companies to attract, hire, train, develop, and manage the best talents in order to achieve the strategic and operational goals of the organization [

1]. Among the different talents, foreign employees with a diverse set of skills are regarded as critical for firms seeking to remain competitive in global markets [

2]. Moreover, different scholars considered them to be key factors in the success of many organizations [

3]. Reachability to highly educated and skilled global human resources not only helps global firms implement their business strategies but also helps to fill the depleted talent pool of domestic organizations [

4] and meet the need for cross-cultural flexible talents [

5]. With the rise of globalization and ease of mobility, different countries, especially in the west, have witnessed a rapid increase in the number of talented foreign employees [

6], which has prompted various researchers to focus on this segment of the market. For instance, in Hungary, foreign employees who work full or part-time in the Hungarian service sector account for nearly 15% of the total employees in this sector [

7,

8]. According to Bove and Elia [

9], an increase in the number of talented foreign employees may bring a variety of new skills and experiences when relocating to the host country, potentially aiding in the acceleration of new technological innovation. From an economic perspective, it may even be beneficial to urban and regional economic growth in host countries [

10]. Therefore, the international employees’ mobility topic has become an important one in the field of management and organization [

11].

Along the same vein, the flow of international students accounts for a considerable part of the emerging high-skilled global labor market [

12,

13]. In many cases, foreign students possess the attributes that employers want in the labor market, as they may have been in the host country for many years, including language skills, cultural familiarity, and adaptability, besides their personal work-related qualifications [

14]. Previous research has shown that hiring foreign students can improve the business experience and innovation ability of the company, as these students may bring cross-cultural experience and ability as well as a new business perspective from their own country [

15]. Therefore, it would be logical to see international graduates as potentially significant resources of skilled labor for the host country in the future [

16].

For international students, their views and experiences regarding staying in the country for work after graduation may change as they experience different aspects of the host country during their study periods [

10]. Working in a foreign country may be different from working at home in a few ways, which could make it hard for them to fit in with the organization of the host country and make them feel isolated [

16]. In this case, the difficulties that the students may encounter in securing suitable employment in the host country are a major factor in their decisions to return to their home countries or to relocate to countries other than the host country [

1]. Some of these factors include the ability to overcome language barriers and fit in with society and are considered among the most significant factors in determining whether international students can obtain employment in the country where they are studying [

13]. These difficulties have been boosted in the last few months as different occasions have hit the economy worldwide generally and in Europe especially, such as the pandemic and the current geopolitical and economic problems that hit the region. Such a crisis may be the main reason for employees to withdraw from the host country, as their stress may increase. Rudolph et al. [

17] mention that in the time of a crisis, the uncertainty and stress among international employees in the host countries increase rapidly; they may further face inequalities and be more negatively impacted economically and emotionally.

Another issue that may push students towards not staying in the host country may stem from the internal policy of the host country. In some Western countries that advocate nationalism or national protectionism, international students are encouraged to return to their home countries after graduation [

18]. For example, the encouragement of foreign students is not a priority policy goal for the Hungarian government as they suggest that those students may be ambassadors to promote Hungarian higher education in their home countries, which may further promote scientific, economic, and cultural ties between Hungary and third-world countries [

19]. The effect of this policy was clear in a recently published report regarding international students who earned degree certificates in Hungary between 2021 and 2019. The report, which was put together by the Tempus Foundation and the Ministry of Education, shows that almost 60% of international graduates no longer live in Hungary [

20]. According to the report, reasons for leaving Hungary after graduation include the need to be close to family; a lack of knowledge of the Hungarian language; attitudes of employers; and labor market conditions, such factors may affect employment opportunities [

20]. Therefore, the organizational roles in providing support for such segments of the labor market may be vital in the intention to stay in Hungary.

The topic of foreign employees in organizations has been attracting different researchers in the last few years [

21]. They are facing increased stress and psychological and economic pressures more than before (as post-effects of the COVID-19 crisis) [

22]. Employees who feel stressed or uncertain would appreciate any type of support from their organizations, which could help them cope with the difficulties that they may face and integrate into the host country [

23]. Thus, POS may be a fundamental factor that predicts the intention of employees to stay in the host country. When employees perceive that their organization’s management supports them, they tend to consider it as evidence that their organization cares about them and their needs; employees translate this positively and reciprocate with positive behaviors [

24]. Additionally, when employees perceive that the required support is available to assist them in adjusting to work and life in the host country, it will have a favorable impact on their social interactions with their organization. In turn, this may have a positive influence on work and non-work-related expatriation outcomes (such as job satisfaction and adjustment in the host country) [

25]. POS has also been linked to intercultural adjustment as a way to reduce stress in other studies [

26]. Intercultural adjustment is considered one of the most critical elements that predict the intention to stay in the host country [

23].

According to Tanova and Ajayi [

23], organizational climate plays an important role in this regard. Different studies have linked organizational climate to the intention of foreign employees to stay in the host country. Churchill et al. [

27] have described organizational climate as the sum of the social elements that make up an employee’s work environment. Different dimensions have been suggested for organizational climate based on the way it is viewed [

28,

29], one of these dimensions according to many researchers is conflict management climate (CMC). According to previous studies, an effective CMC can buffer bullying and negative feelings in the workplace, which leads to fewer problems and stress in the workplace. A positive CMC can be a subsequence of perceived organizational support (POS) [

29]. The POS can be considered a significant predictor of organizational climate because it can foster positive attitudes toward it [

30]. It can further reduce stress among the individuals in the organization, which can increase their work satisfaction [

31].

As we could notice in the literature in the Hungarian context, there is little literature on the career intentions of international students and their experiences of looking for jobs after graduation in the host country [

15]. Previous studies have shown that the intentions of international students in Hungary to be employed abroad are influenced by their overseas study experiences and attributes [

32]. However, they did not consider whether their work experiences would affect their intentions to stay. In recent years, Hungary has witnessed a rapid increase in the number of international students that are enrolled in full-time education as different scholarship programs have been offered by both the government and the EU to students from all over the world [

7]. This may provide the Hungarian economy and organizations with good opportunities to attract talents from various backgrounds to work during (or after) their studies. However, it is still not clear how these organizations can change the students’ plans to stay in Hungary, either directly (by providing them with support) or indirectly (by creating a good organizational climate for dealing with conflicts or by helping them adjust to the new culture). With economic and political problems becoming worse, this issue is more important than ever. This study, according to our knowledge, is the first empirical survey of international students in Hungary to investigate how part-time and internship experiences affect their intentions to stay and work in the host country after graduation, which will be important for both Hungarian researchers and managers. The study will attempt to answer the following questions: what effect does POS have on international students who are currently working during their studies in Hungary, and what roles do CMC and intercultural adjustment play in this relationship?

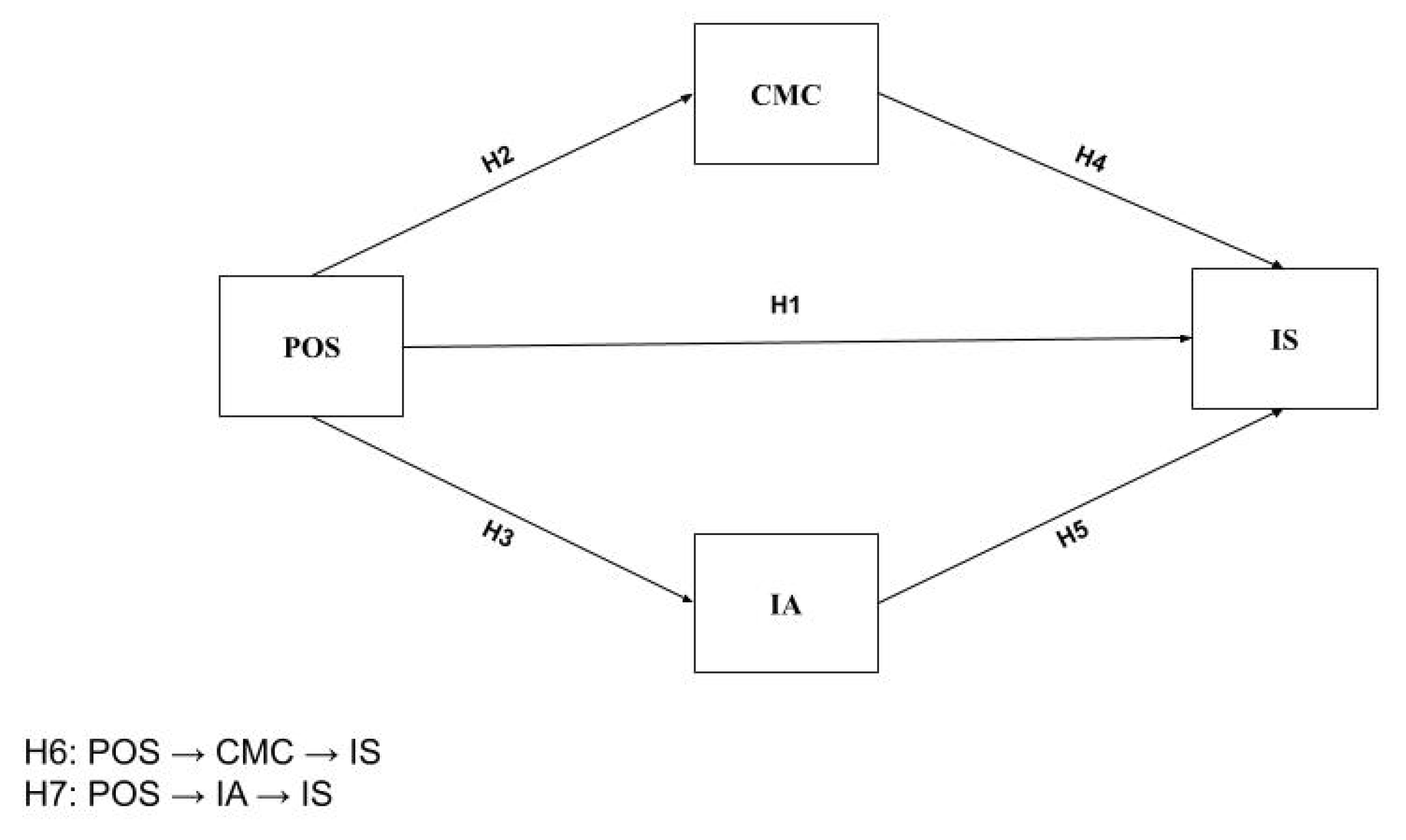

This study’s main objective is to assess the effect of POS on the intention to stay in Hungary of foreign students who work as interns or part-time employees. The research also seeks to determine the roles of CMC and intercultural adjustment in this relationship. In addition, it attempts to demonstrate the connection between POS and CMC and intercultural adjustment, respectively. This paper begins by introducing the theoretical background of the research, reviewing the relevant literature, and putting forward the research hypothesis and the conceptual framework for the study. In the next section, data collection and analysis are presented, and then the results are discussed. Lastly, the paper concludes with research limitations and directions for future research.

5. Discussion

This study focused on international students who came to Hungary for the purpose of studying and who later obtained a part-time job or internship during (or at the end of) their studies. The primary purpose of this study was to find out how the current organizational support that is perceived by these segments of employees is reflected in their intention of staying in Hungary. The study also attempted to figure out what role conflict management climate and intercultural adjustment play in this relationship, since these two variables may have direct effects on how long employees want to stay in the country where they are currently staying.

The findings of this study show that perceived organizational support does not have any direct effect on the intentions of employees to stay in the country where they work after university. This result contradicts the previous study [

73], which finds that POS is positively impacting the intention to stay among the females that work in the service sector in the UAE. On the other hand, our results are in line with the study of Cao et al. [

25], who also found that there is no direct relationship between POS and the intentions of employees to stay in their host countries (in German companies).

The results further reveal that POS has a direct positive impact on CMC and that impact is significantly strong, indicating the important role POS plays in building a positive climate for conflict climate among the employees in Hungary. This result is in line with previous studies that shed light on this relationship [

75,

111]. Therefore, our results confirm again the importance of POS in achieving a positive climate for conflict among the foreign employees that work in Hungary.

In addition, our results highlight the role of POS in promoting intercultural adjustment, which indicates that when employees perceive organizational support at work, they will feel better adjusted to work, general living, and interactions at work. These results are consistent with findings from prior research on the importance of POS for expatriate workers’ intercultural adjustment in the host country [

26,

83].

Subsequently, the findings reveal that the conflict management climate does not have any impact on the intention to stay among international employees in Hungary. That means that CMC does not effectively change the intentions of employees to stay in their host countries. This result is contrary to some previous studies that indicate the role of organizational climate in motivating employees to stay in their host countries (e.g., [

23]). While the employees’ intercultural adjustment is positively associated with higher levels of the intention to stay in the host country, this result is in line with previous studies that have given attention to this relationship [

23,

73].

When testing mediation, the results show that only intercultural adjustment could be a mediator between POS and the intention to stay. This means that if employees have a positive perception of organizational support, they are likely to be more interculturally adjusted inside and outside of the organization, which in turn reflects their intentions to stay in the host country. The results also showed that although POS alone, with the absence of any mediator, could be a predictor of the intention to stay in Hungary, when intercultural adjustment is effective, the role of POS is weak and not very important in the intention to stay in Hungary.

6. Conclusions and Limitations

With the increasing number of students going abroad for further study, their career development choices and directions may also change greatly. Among them, the important impacts of this change are the internships or part-time work experiences these students obtain while studying (or at the end of their courses), which enable international students to gain work experiences and subsidize the cost of living. They can also greatly enhance international students’ perceptions of the organizational climate of the host country’s enterprises. This study mainly examined the possible roles of conflict management climate (CMC) and intercultural adjustment (IA) in the relationship between perceived organizational support (POS) and the intention to stay (IS) in Hungary to work after graduation.

The results of the analysis show that, unlike what was expected, perceived organizational support does not have a direct impact on international students’ intention to stay in Hungary. However, the perceived organizational support of international students could promote their intercultural adjustment, which further has a great impact on their intentions to stay and work abroad. In addition, it is also worth noting that the intercultural adjustment of international students is the only factor that has a direct and significant effect on the intention to stay and work in Hungary in this study. Thus, by providing more help from organizations’ management to international students, they are more likely to stay and work in the host country as they will be more interculturally adjusted. Besides the aforementioned findings, the results also show that POS is directly enhancing CMC and intercultural adjustment among the students, which could be important for maintaining a healthy work environment for organizations.

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

The study contributed to the relatively scarce literature on international students from Hungarian-based contexts, which, for the first time, specifically combines international students’ part-time or internships with their post-graduation mobility intentions. In this sense, the study identifies the factors affecting the intention to stay of international students in Hungary from a new perspective, the organizational climate of the enterprise. This undoubtedly expands the important factors affecting the intention to stay in the literature and also opens up a new path for related research in the future.

6.2. Practical Contributions

This study has implications for helping to deepen international students’ understanding of the factors affecting their staying in the host country after graduation. For international students, it is imperative to focus on enhancing the ability to interculturally adjust during their studies. This involves linking the awareness of self-adjustment with actual internship and part-time experience to consciously develop and adapt to the organizational environment of the host country’s enterprises. For companies interested in strengthening employee diversity, given the link between intercultural adjustment and the retention of international students, understanding the changes in their adjustment and their determinants is essential to developing appropriate recruitment and retention strategies.

The study also connected the organizational context with the intention to stay in the country, indicating the role of organizations in affecting the decisions of those foreign talents to stay in the host country. The study can also be important for managers in Hungary as it showed that when there are employees with good intercultural adjustment, the importance of POS is insignificant. This is significant because if organizations can ensure positive intercultural adjustment among their foreign employees, they may be less stressed in providing support for these employees, potentially saving organizations’ resources in the long run.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

There are several limitations to this study. First, the study samples are only from international students in Hungary, thus reducing the generalizability of our study. As noticed by the researchers, Hungarian companies prefer to recruit and retain Hungarian-speaking employees; language has become a great obstacle for international students to stay in Hungary after graduation, which in turn could be a hidden factor for students not staying in the host country that impacts their intentions to stay indirectly, which could be considered another limitation. Second, the study examined the possible impact of POS on the intention to stay in the host country through two variables. However, only one of them has a direct impact on it. Based on these limitations, the researchers suggest that future research studies test more factors that impact the intention to stay in the host country and focus more on language knowledge as a moderator in the relationship, which eventually may produce more comprehensive and in-depth results.