Cittàslow as An Alternative Path of Town Development and Revitalisation in Peripheral Areas: The Example of The Lublin Province

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Essence of Revitalisation Processes and Cittàslow Movement

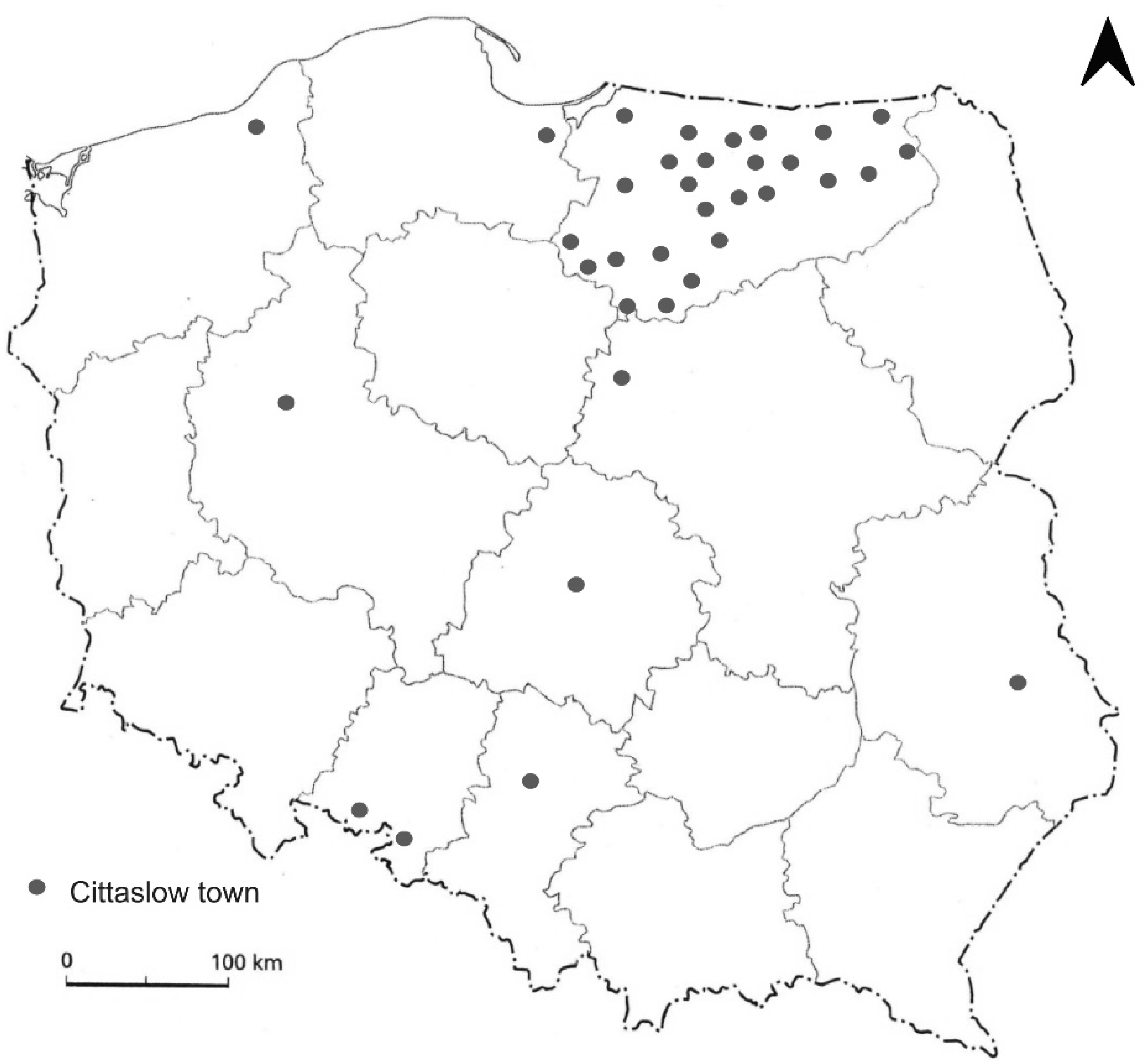

1.2. Revitalisation and Cittàslow in Poland

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Examination Procedures

- Change in population size per 1000 inhabitants;

- Share of pre-working age population in total population in 2020 in %;

- Share of working age population in total population in 2020 in %;

- Share of post-working age population in total population in 2020 in %;

- Post-working age population per 100 working age population in 2020;

- Feminisation rate in 2020;

- Average three-year (2019–2020) population growth rate in ‰;

- Average three-year (2019–2020) net migration rate in ‰;

- Number of employed people per 1000 inhabitants in 2020;

- Entities entered in the National Official Business Register (REGON) per 10,000 inhabitants in 2020;

- Entities newly registered in the National Official Business Register (REGON) per 10,000 inhabitants 2020;

- Foundations, associations and social organisations per 10,000 inhabitants in 2020;

- Business support institutions per 10,000 national economy entities in 2020;

- Share of I&R enterprises in the total number of enterprises in 2020 in %;

- Number of SME (0–249 people) per 10,000 inhabitants;

- Number of apartments per 1000 inhabitants in 2020;

- Average usable floor space per 1 person in m2 in 2020;

- Length of the water supply network in km per 100 km2 in 2020;

- Length of the sewage network in km per 100 km2 in 2020;

- Length of the gas distribution network in km per 100 km2 in 2020;

- Water supply coverage in % of the total population in 2020;

- Sanitation coverage in % of the total population in 2020; and

- Gas grid coverage in % of total population in 2020.

3. Results

3.1. Typology of the Towns of the Lublin Province

- -

- A metropolitan centre designated to boost international and national functions (Lublin) and a local centre participating in the development of metropolitan functions (Świdnik).

- -

- Sub-regional centres (four towns) (Biała Podlaska, Chełm, Puławy and Zamość).

- -

- Local urban centres that play an important role in the functions of the public sector, designated for the strengthening and development of sub-regional functions (six towns) (Biłgoraj, Hrubieszów, Janów Lubelski, Kraśnik, Łuków and Włodawa).

- -

- Local urban centres performing an important public sector function (nine towns) (Biłgoraj, Hrubieszów, Janów Lubelski, Krasnystaw, Kraśnik, Lubartów, Łęczna, Łuków, Międzyrzec Podlaski, Opole Lubelskie, Parczew, Radzyń Podlaski, Ryki, Tomaszów Lubelski and Włodawa).

- -

- Urban centres designated for boosting national and regional specialist functions (nine towns) (Kazimierz Dolny, Zwierzyniec, Nałęczów, Krasnobród, Dęblin, Szczebrzeszyn, Terespol, Poniatowa and Rejowiec Fabryczny).

- -

- Urban centres in which basic functions are concentrated and which are places of development of supra-local specialist functions (14 towns) (Annopol, Józefów, Kock, Modliborzyce, Ostrów Lubelski, Stoczek Łukowski, Łaszczów, Urzędów, Tyszowce, Tarnogród, Frampol, Lubycza Królewska, Siedliszcze and Rejowiec), as well as centres supporting the diffusion of the metropolitan potential (three towns) (Piaski, Bychawa and Bełżyce).

3.2. Findings of the Survey

3.3. Case Studies

- -

- To improve the quality of life of the inhabitants of the revitalisation areas (Bełżyce, Janów Lubelski, Poniatowa and Włodawa);

- -

- To develop local entrepreneurship in the revitalisation areas and increase the level of economic activity of its inhabitants (Bełżyce, Janów Lubelski, Poniatowa and Włodawa); and

- -

- To ensure a high-quality of the environment, among others, by increasing the cleanliness and aesthetics of green areas (Bełżyce, Janów Lubelski and Poniatowa).

- -

- To increase the attractiveness of the revitalisation areas by ensuring a high quality and availability of technical, transport and socio-economic infrastructure (Bełżyce and Janów Lubelski);

- -

- To improve safety (Janów Lubelski and Włodawa);

- -

- To counteract social exclusion by limiting social pathology in the revitalisation areas (Włodawa and Poniatowa);

- -

- To improve the technical condition and energy efficiency of public buildings and housing stock (Janów Lubelski); and

- -

- To revive tourism through the use of local resources and to design attractive and functional public spaces, equipped with appropriate infrastructure to serve the needs of residents and entrepreneurs (Poniatowa).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dmytrenko, A.; Kuzmenko, T.; Kobylarczyk, J.; Paprzyca, K. The Problems of Small Towns in Ukraine and Poland. Tech. Trans. 2019, 10, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harasimowicz, A. Suburbanizacja a Rola Obszarów Otaczających Miasto–Ujęcie Teoretyczne. Stud. Miej. 2018, 29, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffner, K. Procesy Suburbanizacji a Polityka Miejska w Polsce. In Miasto—Region—Gospodarka w Badaniach Geograficznych. W stulecie Urodzin Profesora Ludwika Straszewicza; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2016; pp. 75–110. [Google Scholar]

- Pucherová, Z.; Mišovičová, R.; Bugár, G.; Grežo, H. Changes in Landscape Structure in the Municipalities of the Nitra District (Slovak Republic) Due to Expanding Suburbanization. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykała, Ł. Główne Wyzwania Rozwojowe Polskich Miast-Elementy Diagnozy; Obserwatorium Polityki Miejskiej IRMiR; Instytut Rozwoju Miast i Regionów: Warszawa-Kraków, Poland, 2019; pp. 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Musiał-Malago, M. Wybrane Aspekty Kurczenia Się Miast w Polsce. Stud. Miej. 2018, 29, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasse, A.; Bernt, M.; Großmann, K.; Mykhnenko, V.; Rink, D. Varieties of Shrinkage in European Cities. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2013, 23, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Fernandez, C.; Audirac, I.; Fol, S.; Cunningham-Sabot, E. ‘Shrinking Cities: Urban Challenges of Globalization. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2012, 36, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, R.; Bagchi-Sen, S.; Knight, J.; Frazer, A. Shrinking Cities: Understanding Urban Decline in the United States; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Siedentop, S.; Fina, S. Urban Sprawl beyond Growth: The Effect of Demographic Change on Infrastructure Costs. Flux 2010, 1, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroka, B. Dychotomia Procesu Urbanizacji, Czyli Rozlewanie Miast Kurczących Się w Kontekście Systemu Planowania Przestrzennego; Instytut Rozwoju Miast i Regionów: Warszawa, Poland; Kraków, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Stryjakiewicz, T.; Jaroszewska, E.; Marcińczak, S.; Ogrodowczyk, A.; Rumpel, P.; Siwek, T.; Slach, O. Współczesny Kontekst i Podstawy Teoretyczno-Metodologiczne Analizy Procesu Kurczenia Się Miast. In Kurczenie Się Miast w Europie Środkowo-Wschodniej; Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Poznań, Poland, 2014; pp. 9–14. ISBN 978-83-7986-024-1. [Google Scholar]

- Musiał-Malago, M. Problematyka identyfikacji i pomiaru procesu kurczenia się miast. Biuletyn KPZK PAN 2018, 272, 174–187. [Google Scholar]

- Szymańska, D.; Grzelak-Kostulska, E. Problematyka Małych Miast w Polsce w Świetle Literatury. Biul. KPZK PAN 2005, 220, 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gzell, S. Fenomen Małomiejskości; Akapit DTP: Warszawa, Poland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mania, W. Współczesne Transformacje i Zagrożenia Krajobrazów Małych Miast. Pr. Kom. Kraj. Kult. PTG 2008, 10, 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Górski, Ł.; Maćkiewicz, B.; Rutkowski, A. Przynależność Do Polskiej Krajowej Sieci Cittaslow a Rynek Nieruchomości. In Alternatywne Modele Rozwoju Miast. Sieć miast Cittàslow; Monografie; Politechnika Łódzka: Łódź, Poland, 2017; pp. 123–134. ISBN 978-83-7283-826-1. [Google Scholar]

- Strzelecka, E. (Ed.) Alternatywne Modele Rozwoju Miast. Sieć Miast Cittaslow; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Łódzkiej: Łódź, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honoré, C. Praise of Slow: How a Worldwide Movement Is Challenging the Cult of Speed, Paperback Ed. ed; Orion: London, UK, 2005; ISBN 978-0-7528-6414-3. [Google Scholar]

- Strzelecka, E. Rewitalizacja Miast w Kontekście Zrównoważonego Rozwoju. Bud. I Inżynieria Sr. 2011, 2, 661–668. [Google Scholar]

- Lorens, P. Rewitalizacja Miast w Polsce. Pierwsze Doświadczenia; Urbanista: Warszawa, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Strzelecka, E. Network Model of Revitalization in the Cittàslow Cities of the Warmińsko-Mazurskie Voivodship. Barom. Reg. 2018, 3, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farelnik, E. Revitalisation as a Tool for the Development of Slow City (Cittaslow). JESI 2021, 9, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaszczak, A.; Kristianova, K.; Pochodyła, E.; Kazak, J.K.; Młynarczyk, K. Revitalization of Public Spaces in Cittaslow Towns: Recent Urban Redevelopment in Central Europe. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaszczak, A.; Pochodyła, E.; Płoszaj-Witkowska, B. Transformation of Green Areas in Central Squares after Revitalization: Evidence from Cittaslow Towns in Northeast Poland. Land 2022, 11, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska-Szczepkowska, J.; Jaszczak, A.; Žukovskis, J. Overcoming Socio-Economic Problems in Crisis Areas through Revitalization of Cittaslow Towns. Evidence from North-East Poland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manella, G.; de Salvo, P.; Calzati, V. Verso Modelli Di Governo Urbano Sostenibile e Solidale: Il Caso Cittaslow in Emilia-Romagna. Sociol. Urbana Rural. 2017, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presenza, A.; Perano, M. The Cittaslow Certification and Its Effects on Sustainable Tourism Governance. SSRN J. 2015, 5, 40–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radstrom, S. A Place-Sustaining Framework for Local Urban Identity: An Introduction and History of Cittàslow. Ital. J. Plan. Pract. 2011, 1, 90–113. [Google Scholar]

- Zagroba, M.; Pawlewicz, K.; Senetra, A. Analysis and Evaluation of the Spatial Structure of Cittaslow Towns on the Example of Selected Regions in Central Italy and North-Eastern Poland. Land 2021, 10, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, H.; Knox, P.L. Slow Cities: Sustainable Places in a Fast World. J. Urban Aff. 2006, 28, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sept, A.; Potz, P. Cittàslow-Germany: Dove i Piccoli Centri Urbani Si Rappresentano. U3 I Quad. 2013, 3, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sept, A. ‘Slowing down’ in Small and Medium-Sized Towns: Cittaslow in Germany and Italy from a Social Innovation Perspective. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2021, 8, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur-Belzyt, K. Współczesne Podstawy Rozwoju Małych Miast Na Przykładzie Sieci Miast Cittàslow. Probl. Rozw. Miast 2014, 3, 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Szczepańska, A.; Pietrzyk, K. Perspektywa Rozwoju Sieci Miast Cittaslow w Regionie Warmii i Mazur Na Przykładzie Morąga. Acta Sci. Pol. Adm. Locorum 2018, 17, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadęcka, E. ”Slow City” as a Local Development Model. Econ. Reg. Stud./Stud. Ekon. I Reg. 2018, 11, 84–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaszczak, A.; Kristianova, K. Social and Cultural Role of Greenery in Development of Cittaslow Towns. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 603, 032028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaszczak, A.; Morawiak, A.; Żukowska, J. Cycling as a Sustainable Transport Alternative in Polish Cittaslow Towns. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senetra, A.; Szarek-Iwaniuk, P. Socio-Economic Development of Small Towns in the Polish Cittaslow Network—A Case Study. Cities 2020, 103, 102758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzbicka, W. Socio-Economic Potential of Cities Belonging to the Polish National Cittaslow Network. Oeconomia Copernica 2020, 11, 203–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodziński, Z.; Kurowska, K. Cittaslow Idea as a New Proposition to Stimulate Sustainable Local Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadzka, A.K. Architectural and Urban Attractiveness of Small Towns: A Case Study of Polish Coastal Cittaslow Towns on the Pomeranian Way of St. James. Land 2021, 10, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzbicka, W. Activities Undertaken in the Member Cities of the Polish National Cittaslow Network in the Area of “Energy and Environmental Policy”. Energies 2022, 15, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadway, M. Implementing the Slow Life in Southwest Ireland: A Case Study of Clonakilty and Local Food. Geogr. Rev. 2015, 105, 216–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pink, S.; Servon, L.J. Sensory Global Towns: An Experiential Approach to the Growth of the Slow City Movement. Environ. Plan. A 2013, 45, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadzka, A.K. Accessibility of Polish and Nordic Cittàslow Towns. Barom. Reg. 2018, 16, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pink, S.; Lewis, T. Making Resilience: Everyday Affect and Global Affiliation in Australian Slow Cities. Cult. Geogr. 2014, 21, 695–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Kim, S. The Potential of Cittaslow for Sustainable Tourism Development: Enhancing Local Community’s Empowerment. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2016, 13, 351–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmens, J.; Freeman, C. The Value of Cittaslow as an Approach to Local Sustainable Development: A New Zealand Perspective. Int. Plan. Stud. 2012, 17, 353–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ada, E.; Yener, D. Peyzaj Potansïyelïnïn Korunmasinda Cittaslow-Slow City Bïrlïğïnïn Değerlendïrïlmesï. İnönü Üniv. Sanat Ve Tasarım Derg. 2017, 7, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kalisiak, A. Analiza Możliwości Włączenia Rawy Mazowieckiej Do Sieci Cittàslow w Kontekście Doświadczeń Lidzbarka Warmińskiego. In Alternatywne Modele Rozwoju Miast. Sieć Miast Cittàslow; Monografie; Politechnika Łódzka: Łódź, Poland, 2017; pp. 282–302. ISBN 978-83-7283-826-1. [Google Scholar]

- Szczepańska, M.; Świderski, A. Idea Miast Dobrego Życia—Cittàslow. Diagnoza Możliwości Przystąpienia Miasta Sierakowa Do Sieci Cittàslow w Kontekście Procesów Rewitalizacyjnych. Rozw. Reg. I Polityka Reg. 2017, 39, 155–173. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek, U. Koncepcja Slow City i Jej Wdrażanie w Małych Miastach Obszaru Metropolitalnego. Przykład Murowanej Gośliny i Schneverdingen. Rozw. Reg. I Polityka Reg. 2019, 48, 119–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernat, S.; Flaga, M. Landscape of Small Towns in Lubelskie Province. Part 1–Problems of Landscape Shaping. Diss. Cult. Landsc. Comm. 2020, 43, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajdys, D.; Ślebocka, M. Rewitalizacja Miast We Współpracy z Podmiotem Prywatnym w Formule Partnerstwa Publiczno-Prywatnego; Edu-Libri: Kraków, Poland; Legionowo, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ustawa z Dnia 9 Października 2015 r. o Rewitalizacji. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu20150001777 (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- Jarczewski, W.; Kułaczkowska, A. Rewitalizacja: Raport o Stanie Polskich Miast; Instytut Rozwoju Miast i Regionów: Warszawa, Poland; Kraków, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jadach-Sepioło, A.; Tomczyk, E.; Spadło, K.; Lipczyńska, K.; Sęk, P.; Sochaczewska, M. (Eds.) Ewaluacja Systemu Zarządzania i Wdrażania Procesów Rewitalizacji w Polsce; Instytut Rozwoju Miast i Regionów: Warszawa, Poland; Kraków, Poland, 2021; ISBN 978-83-65105-67-7. [Google Scholar]

- Konecka-Szydłowska, B. Zróżnicowanie Polskiej Sieci Miast Cittàslow w Aspekcie Społeczno-Gospodarczym. In Alternatywne Modele Rozwoju Miast. Sieć Miast Cittaslow; Politechnika Łódzka: Łódź, Poland, 2017; pp. 61–73. ISBN 978-83-7283-826-1. [Google Scholar]

- Szarek-Iwaniuk, P. Potencjały i Bariery Rozwoju Małych i Średnich Miast Na Przykładzie Polskiej Krajowej Sieci Miast Cittaslow. ZP 2019, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dams-Lepiarz, M. Małe Miasta w Sieci Osadniczej Województwa Lubelskiego w Okresie Transformacji Ustrojowej w Polsce. Ann. UMCS 2003, 58, 157–172. [Google Scholar]

- Mazur-Belzyt, K. Małe Miasta w Dobie Równoważenia Rozwoju; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Śląskiej: Gliwice, Poland, 2018; ISBN 978-83-7880-537-3. [Google Scholar]

- Zadęcka, E. Cittàslow-Koncepcja Dobrego Życia w Małym Mieście. Stud. Ekon. 2018, 348, 129–143. [Google Scholar]

- Twardzik, M. Wyzwania Rozwojowe Dla Małych Miast w Polsce—Przegląd Wybranych Koncepcji. Stud. Ekon. 2017, 327, 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Batyk, I.; Woźniak, M. Benefits of Belonging to the Cittaslow Network in the Opinion of Residents of Member Cities. Econ. Reg. Stud./Stud. Ekon. I Reg. 2019, 12, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furmankiewicz, M.; Królikowska, K. Partnerstwa Terytorialne: Na Obszarach Wiejskich w Polsce w Latach 1994–2006; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2010; ISBN 978-83-7717-021-2. [Google Scholar]

- Miszczuk, A. Uwarunkowania Peryferyjności Regionu Przygranicznego; Norbertinum: Lublin, Poland, 2013; ISBN 978-83-7222-494-1. [Google Scholar]

- Wesołowska, M. Wsie Znikające w Polsce: Stan, Zmiany, Modele Rozwoju; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej: Lublin, Poland, 2018; ISBN 978-83-227-9137-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bernat, S.; Kałamucka, W. Krajobraz w Doświadczeniu Mieszkańców Wiejskich Obszarów Peryferyjnych Na Przykładzie Woj. Lubelskiego. Stud. Obsz. Wiej. 2011, 26, 189–202. [Google Scholar]

- Przesmycka, E. Przeobrażenia Zabudowy i Krajobrazu Miasteczek Lubelszczyzny; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Lubelskiej: Lublin, Poland, 2001; ISBN 978-83-88110-04-7. [Google Scholar]

- Strategia Rozwoju Społeczno-Gospodarczego Polski Wschodniej Do Roku 2020. In Aktualizacja, Załącznik do Uchwały 121; Ministerstwo Rozwoju Regionalnego: Warszawa, Poland, 2013.

- Jakubowski, A.; Bronisz, U. Konkurencyjność Pogranicza Polsko-Ukraińskiego Na Tle Europejskim. In Wyzwania Rozwojowe Pogranicza Polsko-Ukraińskiego; Wydawnictwo Norbertinum: Lublin, Poland, 2017; pp. 35–59. ISBN 978-83-7222-610-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kałamucka, W. Jakość Życia i Zabezpieczenie Egzystencji z Perspektywy Geograficznej; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej: Lublin, Poland, 2017; ISBN 978-83-7784-942-2. [Google Scholar]

- Flaga, M. Model Przemian Demograficznych w Regionach Wyludniaja̜cych sie̜ Polski: Na Przykladzie Wojewodztwa Lube; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej: Lublin, Poland, 2018; ISBN 978-83-227-9157-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bank Danych Lokalnych GUS. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Ward, J.H. Hierarchical Grouping to Optimize an Objective Function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1963, 58, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strulak-Wójcikiewicz, R.; Łatuszyńska, M. Metody Oceny Oddziaływania Przedsięwzięć Inwestycyjnych Na Środowisko Naturalne. Stud. I Pr. Wydziału Nauk. Ekon. I Zarządzania 2014, 37, 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Heffner, K.; Solga, B. Lokalne Centra Rozwoju Obszarów Wiejskich—Znaczenie i Powiązania Małych Miast. Stud. Obsz. Wiej. 2000, 11, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Regionalna Polityka Miejska Województwa Lubelskiego 2017. Available online: https://rpo.lubelskie.pl/ (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- Bartłomiejski, R.; Kowalewski, M. Polish Urban Allotment Gardens as ‘Slow City’ Enclaves. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R. Meaningful Types in a World of Suburbs. Suburbanization in Global Society. Res. Urban Sociol. 2010, 10, 15–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarczewski, W.; Sroka, B. Kurczenie Się Polskich Miast a Rewitalizacja. In Raport o Stanie Polskich Miast: Rewitalizacja; IRMIR: Kraków, Poland; Warszawa, Poland, 2019; pp. 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Champion, T. Urbanization, Suburbanization, Counterurbanization and Reurbanization. In Handbook of Urban Studies; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2001; pp. 143–161. [Google Scholar]

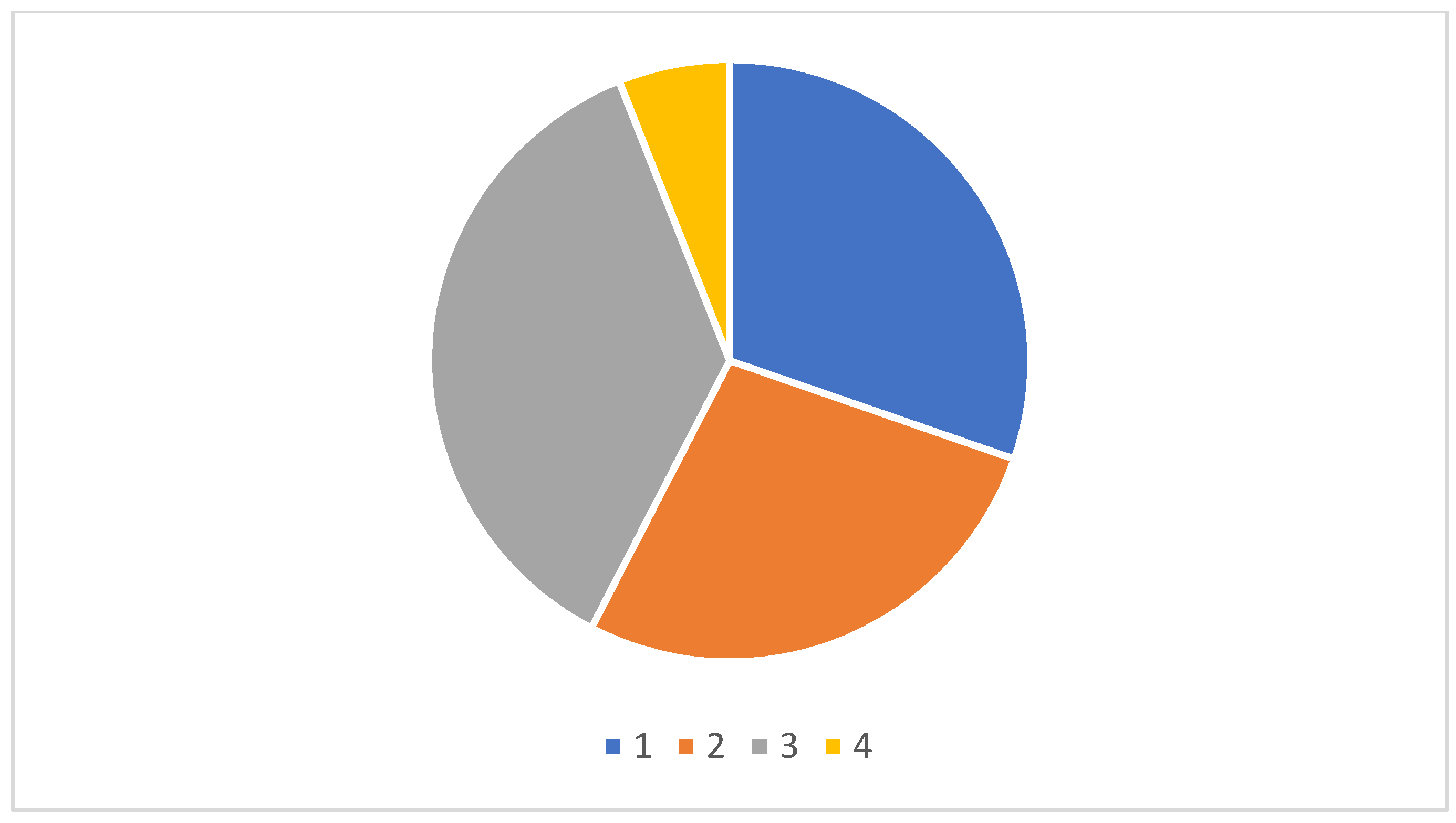

| Category 1: Energy and environmental policy |

|

| Category 2: Infrastructure policy |

|

| Category 3: Quality of urban life policy |

|

| Category 4: Agricultural, artisan and tourist policies |

|

| Category 5: Policies for hospitality, training and awareness |

|

| Category 6: Social cohesion |

|

| Category 7: Partnerships |

|

| County | Towns by County | Area in Ha | Population in Number of People | Population Density (People/km2) | Town Privileges Granted (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bialski | Międzyrzec Podlaski | 2003 | 16,667 | 832 | 1440/41 |

| bialski | Terespol | 1011 | 5457 | 540 | 1779 |

| biłgorajski | Biłgoraj | 2110 | 26,114 | 1238 | 1578 |

| biłgorajski | Frampol | 467 | 4041 | 60 | 1993 (1736) |

| biłgorajski | Goraj | 762 | 917 | 127 | 2021 (1405) |

| biłgorajski | Józefów | 500 | 2473 | 495 | 1988 (1725) |

| biłgorajski | Tarnogród | 1069 | 3304 | 309 | 1987 (1567) |

| chełmski | Rejowiec Fabryczny | 1428 | 4328 | 303 | 1962 |

| chełmski | Siedliszcze | 1316 | 1406 | 107 | 2016 (1548) |

| chełmski | Rejowiec | 650 | 2026 | 312 | 2017 (1547) |

| hrubieszowski | Hrubieszów | 3303 | 17,232 | 522 | 1400 |

| janowski | Janów Lubelski | 1480 | 11,661 | 788 | 1640 |

| janowski | Modliborzyce | 789 | 1459 | 185 | 2014 (1642) |

| krasnostawski | Krasnystaw | 4213 | 8028 | 58 | 1394 |

| krasnostawski | Izbica | 947 | 1933 | 204 | 2022 (1750) |

| kraśnicki | Kraśnik | 2610 | 33,917 | 1300 | 1919 (1377) |

| kraśnicki | Annopol | 773 | 2436 | 315 | 1996 (1761) |

| kraśnicki | Urzędów | 1291 | 1679 | 130 | 2016 (1405) |

| lubartowski | Lubartów | 1391 | 21,636 | 1555 | 1543 |

| lubartowski | Kamionka | 589 | 1712 | 365 | 2021 (1450) |

| lubartowski | Kock | 1678 | 3238 | 193 | 1919 (1417) |

| lubartowski | Ostrów Lubelski | 2977 | 2089 | 70 | 1919 (1548) |

| lubelski | Bełżyce | 2346 | 6399 | 273 | 1958 (1417) |

| lubelski | Bychawa | 669 | 4814 | 720 | 1958 (1537) |

| łęczyński | Łęczna | 1900 | 18,675 | 983 | 1467 |

| łukowski | Łuków | 3575 | 29,441 | 824 | 1369 |

| łukowski | Stoczek Łukowski | 915 | 2480 | 271 | 1916 (1546) |

| opolski | Józefów nad Wisłą | 365 | 902 | 247 | 2018 (1687) |

| opolski | Opole Lubelskie | 1512 | 8320 | 550 | 1418 |

| opolski | Poniatowa | 1526 | 8980 | 588 | 1962 |

| parczewski | Parczew | 805 | 10,555 | 1311 | 1401 |

| puławski | Puławy | 5049 | 46,965 | 930 | 1906 |

| puławski | Kazimierz Dolny | 3044 | 2534 | 83 | 1927 (14th c.) |

| puławski | Nałęczów | 1382 | 3727 | 270 | 1963 |

| radzyński | Radzyń Podlaski | 1931 | 15,428 | 799 | 1468 |

| rycki | Dęblin | 3833 | 15,887 | 414 | 1954 |

| rycki | Ryki | 2722 | 9531 | 350 | 1957 (1782) |

| świdnicki | Świdnik | 2035 | 38,763 | 1905 | 1954 |

| świdnicki | Piaski | 844 | 2531 | 300 | 1993 (1456) |

| tomaszowski | Tomaszów Lubelski | 1329 | 18,783 | 1413 | 1621 |

| tomaszowski | Lubycza Królewska | 392 | 2424 | 618 | 2016 (1759) |

| tomaszowski | Łaszczów | 501 | 2111 | 421 | 2010 (1549) |

| tomaszowski | Tyszowce | 1852 | 2054 | 111 | 2000 (1419) |

| włodawski | Włodawa | 1797 | 12,915 | 719 | 1534 |

| zamojski | Krasnobród | 699 | 3074 | 440 | 1994 |

| zamojski | Szczebrzeszyn | 2912 | 4962 | 170 | 1352 |

| zamojski | Zwierzyniec | 619 | 3101 | 501 | 1990 |

| Town | Share of Parks, Town Greens and Green Areas in Neighbourhoods in the Total Town Area (%) | Share of Green Areas in the Total Town Area (%) | Number of Beds in Year-Round Accommodation Facilities | Number of Public Libraries Per 10,000 Inhabitants | Number of Cultural Centres, Clubs and Community Centres Per 10,000 Inhabitants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bełżyce | 2.3 | 3.22 | no data | 3.1 | 1.6 |

| Janów Lubelski | 0.7 | 2.66 | 288 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Poniatowa | 1.3 | 2.21 | 160 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Włodawa | 2.0 | 3.86 | 0 | 1.5 | 0.8 |

| Town | Programme Type M—Municipal C—Communal | Percent of Town Area under Revitalisation (%) | Mean for Lublin Province Towns with <50,000 Inhabitants | Number of Projects | Mean for Lublin Province Towns with <50,000 Inhabitants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bełżyce | M | 1.10 | 8.78 | 24 | 20.5 |

| Janów Lubelski | M | 0.8 | 7 | ||

| Poniatowa | M | 10.5 | 18 | ||

| Włodawa | M | 18.63 | 15 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bernat, S.; Flaga, M. Cittàslow as An Alternative Path of Town Development and Revitalisation in Peripheral Areas: The Example of The Lublin Province. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114160

Bernat S, Flaga M. Cittàslow as An Alternative Path of Town Development and Revitalisation in Peripheral Areas: The Example of The Lublin Province. Sustainability. 2022; 14(21):14160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114160

Chicago/Turabian StyleBernat, Sebastian, and Małgorzata Flaga. 2022. "Cittàslow as An Alternative Path of Town Development and Revitalisation in Peripheral Areas: The Example of The Lublin Province" Sustainability 14, no. 21: 14160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114160

APA StyleBernat, S., & Flaga, M. (2022). Cittàslow as An Alternative Path of Town Development and Revitalisation in Peripheral Areas: The Example of The Lublin Province. Sustainability, 14(21), 14160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114160