Explaining Farmers’ Income via Market Orientation and Participation: Evidence from KwaZulu-Natal (South Africa)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

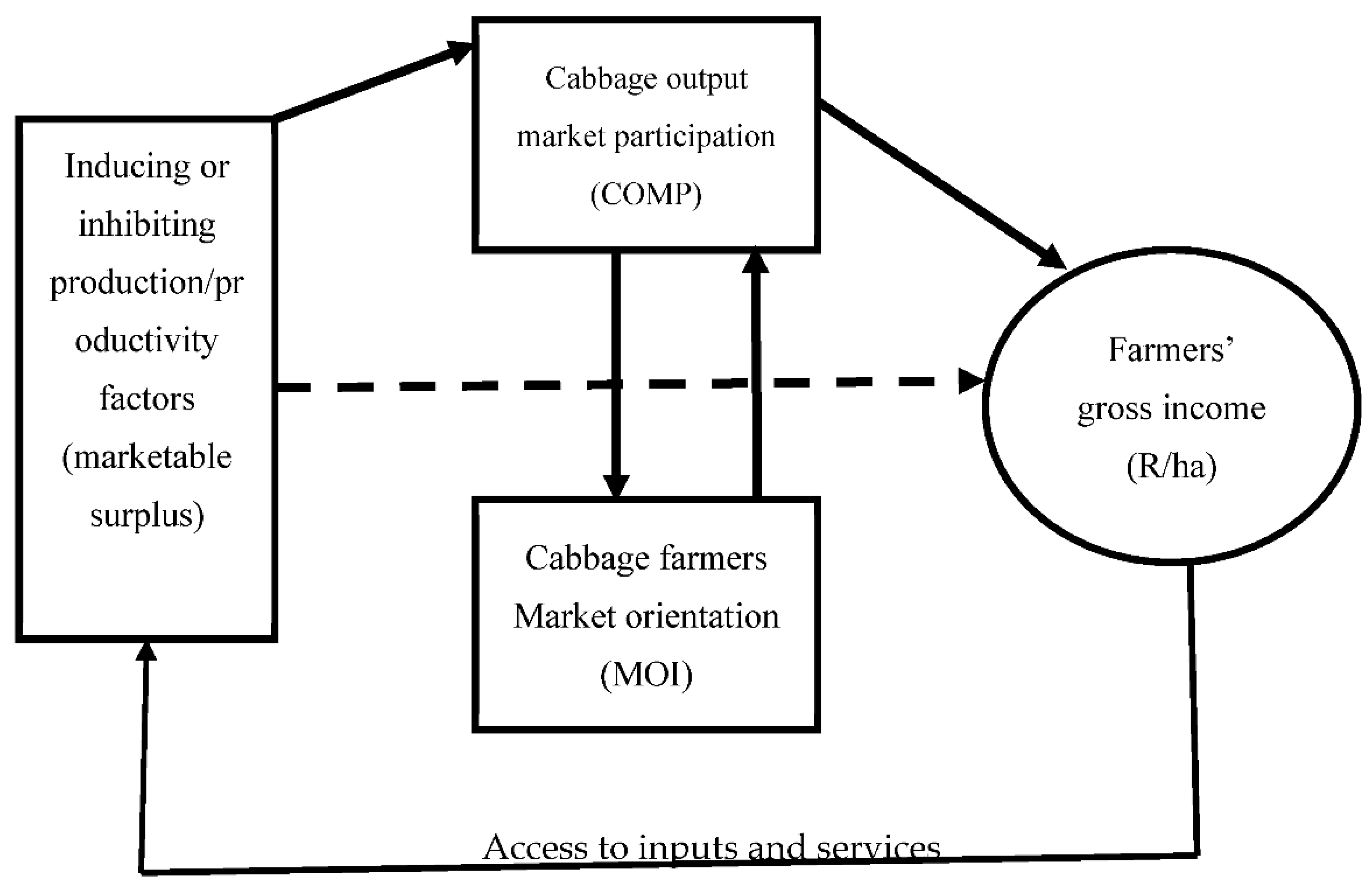

2. Conceptual Framework

3. Empirical Methodology

3.1. Study Area and Sampling

3.2. Cabbage Enterprise

3.3. Empirical Model

3.3.1. Estimation of Market Orientation Index (MOI)

3.3.2. Product Market Participation

3.3.3. Specification of the Two-Limit Tobit Regression Model

3.3.4. Estimation of Ordinary Least Square (OLS) Regression Model

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Descriptive Statistics of Categorical Variables

4.3. The Distribution of Market Participation and Orientation Indices

4.4. Determinants of Cabbage Market Participation

4.5. Determinants of Farmers’ Market Orientation

4.6. Determinants of Cabbage Income per ha

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hulke, C.; Kairu, J.K.; Diez, J.R. Development visions, livelihood realities–how conservation shapes agricultural value chains in the Zambezi region, Namibia. Dev. South. Afr. 2021, 38, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyo, B.; Kalema, B.M. A System Dynamics Model for Subsistence Farmers’ Food Security Resilience in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Syst. Dyn. Appl. IJSDA 2016, 5, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rubhara, T.; Mudhara, M. Commercialization and its determinants among smallholder farmers in Zimbabwe. A case of Shamva District, Mashonaland Central Province. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2019, 11, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremedhin, B.; Jaleta, M. Commercialization of smallholders: Is market participation enough? In Proceedings of the Joint 3rd African Association of Agricultural Economists (AAAE) and 48th Agricultural Economists Association of South Africa (AEASA) Conference, Cape Town, South Africa, 19–23 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, C.B. Smallholder market participation: Concepts and evidence from eastern and southern Africa. Food Policy 2008, 33, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regasa Megerssa, G.; Negash, R.; Bekele, A.E.; Nemera, D.B. Smallholder market participation and its associated factors: Evidence from Ethiopian vegetable producers. Cogent Food Agric. 2020, 6, 1783173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigei, G.; Bett, H.; Kibet, L. Determinants of Market Participation among Small-Scale Pineapple Farmers in Kericho County, Kenya. MPRA Paper 56149. 2014. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/56149/1/MPRA_paper_56149.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2021).

- Jayne, T.S.; Haggblade, S.; Minot, N.; Rashid, S. Agricultural commercialization, rural transformation and poverty reduction: What have we learned about how to achieve this? Gates Open Res. 2019, 3, 678. [Google Scholar]

- Yaseen, A.; Bryceson, K.; Mungai, A.N. Commercialization behaviour in production agriculture: The overlooked role of market orientation. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2018, 8, 579–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaleta, M.; Gebremedhin, B.; Hoekstra, D. Smallholder Commercialization: Processes, Determinants and Impact. ILRI Discussion Paper; International Livestock Research Institute: Nairobi, Kenya, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Iheke, O.R. Market orientation, innovation adoption and performance of food crops farmers in Abia State, Nigeria. Niger. Agric. J. 2021, 52, 188–200. [Google Scholar]

- Fanadzo, M.; Ncube, B. Challenges and opportunities for revitalising smallholder irrigation schemes in South Africa. Water SA 2018, 44, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ortmann, G.F.; King, R.P. Research on agri-food supply chains in Southern Africa involving small-scale farmers: Current status and future possibilities. Agrekon 2010, 49, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Loeper, W.; Musango, J.; Brent, A.; Drimie, S. Analysing challenges facing smallholder farmers and conservation agriculture in South Africa: A system dynamics approach. South Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2016, 19, 747–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWF. Climate Smart Smallholder Farming. 2021. Available online: https://www.wwf.org.za/our_work/initiatives/climate_smart_smallholder_farming/ (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Department of Agriculture. Most common indigenous food crops of South Africa. 2021. Available online: https://www.nda.agric.za/docs/Brochures/Indigfoodcrps.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- Xu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Lagnika, C.; Li, D.; Liu, C.; Jiang, N.; Song, J.; Zhang, M. A comparative evaluation of nutritional properties, antioxidant capacity and physical characteristics of cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. Capitate var L.) subjected to different drying methods. Food Chem. 2020, 309, 124935. [Google Scholar]

- Le Roux, B.; Van der Laan, M.; Vahrmeijer, T.; Annandale, J.G.; Bristow, K.L. Water footprints of vegetable crop wastage along the supply chain in Gauteng, South Africa. Water 2018, 10, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndlovu, P.N.; Thamaga-Chitja, J.M.; Ojo, T.O. Factors influencing the level of vegetable value chain participation and implications on smallholder farmers in Swayimane KwaZulu-Natal. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senyolo, G.M.; Wale, E.; Ortmann, G.F. Analysing the value chain for African leafy vegetables in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2018, 4, 1509417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchara, B.; Ortmann, G.F.; Mudhara, M.; Wale, E. Irrigation water value for potato farmers in the Mooi River Irrigation Scheme of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: A residual value approach. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 164, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.; Ojong, T.; Hauser, M.; Mausch, K. Does agricultural commercialisation increase asset and livestock accumulation on smallholder farms in Ethiopia. J. Dev. Stud. 2022, 58, 524–544. [Google Scholar]

- Phakathi, S.; Wale, E. Explaining variation in the economic value of irrigation water using psychological capital: A case study from Ndumo B and Makhathini, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Water 2018, 44, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gautam, M.; Ahmed, M. Too small to be beautiful? The farm size and productivity relationship in Bangladesh. Food Policy 2019, 84, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muyanga, M.; Jayne, T.S. Revisiting the farm size-productivity relationship based on a relatively wide range of farm sizes: Evidence from Kenya. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2019, 101, 1140–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkomoki, W.; Bavorová, M.; Banout, J. Factors associated with household food security in Zambia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olofsson, M. Socio-economic differentiation from a class-analytic perspective: The case of smallholder tree-crop farmers in Limpopo, South Africa. J. Agrar. Chang. 2020, 20, 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mujuru, N.M.; Obi, A. Effects of cultivated area on smallholder farm profits and food security in rural communities of the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mukwevho, R.; Anim, F.D.K. Factors affecting small scale farmers in accessing markets: A case study of cabbage producers in the Vhembe District, Limpopo Province of South Africa. J. Hum. Ecol. 2014, 48, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zantsi, S.; Cloete, K.; Möhring, A. Productivity gap between commercial farmers and potential emerging farmers in South Africa: Implications for land redistribution policy. Appl. Anim. Husb. Rural. Dev. 2021, 14, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Gebremedhin, B.; Tegegne, A. Market orientation and market participation of smallholders in Ethiopia: Implications for commercial transformation Selected Paper prepared for presentation. In Proceedings of the International Association of Agricultural Economists (IAAE) Triennial Conference, Foz do lguacu, Brazil, 18–24 August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hagos, A.; Dibaba, R.; Bekele, A.; Alemu, D. Determinants of market participation among smallholder mango producers in Assosa Zone of Benishangul Gumuz Region in Ethiopia. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2020, 20, 323–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tindiwensi, C.K.; Munene, J.C.; Sserwanga, A.; Abaho, E.; Namatovu-Dawa, R. Farm management skills, entrepreneurial bricolage and market orientation. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2020, 10, 717–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elum, Z.A.; Modise, D.M.; Marr, A. Farmer’s perception of climate change and responsive strategies in three selected provinces of South Africa. Clim. Risk Manag. 2017, 16, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DAFF. Vegetable Crops. 2015. Available online: http://www.daff.gov.za/publications (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Martey, E.; Etwire, P.M.; Wiredu, A.N.; Ahiabor, B.D. Establishing the link between market orientation and agricultural commercialization: Empirical evidence from Northern Ghana. Food Secur. 2017, 9, 849–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Braun, J. Agricultural commercialization: Impacts on income and nutrition and implications for policy. Food Policy 1995, 20, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, D.; Mitiku, F.; Negash, R. Commercialization level and determinants of market participation of smallholder wheat farmers in northern Ethiopia. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2021, 14, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alphonse, S.; Felix, B.; Jourdain, L.; Hippolyte, A. Market Participation and Technology Adoption: An Application of a Triple-Hurdle Model Approach to Improved Sorghum Varieties in Mali. Sci. Afr. 2021, 13, e00859. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, J.F.; Moffitt, R.A. The uses of Tobit analysis. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1980, 62, 318–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amemiya, T. Advanced Econometrics; T.J. Press Ltd.: Pad Stow, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, W.H. Econometric Analysis; Pearson Education India: Tamil Nadu, India, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, J.; DiNardo, J. Econometric Methods, 4th ed.; McGraw-HiU: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Agriculture. A Profile of the South African Cabbage Market Value Chain. A Profile of the South African Cabbage Market Value Chain. 2014. Available online: https://www.dalrrd.gov.za/doaDev/sideMenu/Marketing/Annual%20Publications/Cabbage%20Market%20Value%20Chain%20Profile%202019.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2021).

- Skinner, C. Street Trade in Africa: A Review. In School of Development Studies Working Paper No. 51; University of KwaZulu-Natal: Durban, South Africa, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, C. The struggle for the streets: Processes of exclusion and inclusion of street traders in Durban, South Africa. Dev. South. Afr. 2008, 25, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mmbando, F.E.; Wale, E.Z.; Baiyegunhi, L.J. Determinants of smallholder farmers’ participation in maize and pigeonpea markets in Tanzania. Agrekon 2015, 54, 96–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngenoh, E.; Kurgat, B.K.; Bett, H.K.; Kebede, S.W.; Bokelmann, W. Determinants of the competitiveness of smallholder African indigenous vegetable farmers in high-value agro-food chains in Kenya: A multivariate probit regression analysis. Agric. Food Econ. 2019, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carletto, C.; Corral, P.; Guelfi, A. Agricultural commercialization and nutrition revisited: Empirical evidence from three African countries. Food Policy 2017, 67, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rabbi, F.; Ahamad, R.; Ali, S.; Chandio, A.A.; Ahmad, W.; Ilyas, A.; Din, I.U. Determinants of commercialization and its impact on the welfare of smallholder rice farmers by using Heckman’s two-stage approach. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2019, 18, 224–233. [Google Scholar]

- Randela, R.; Alemu, Z.G.; Groenewald, J.A. Factors enhancing market participation by small-scale cotton farmers. Agrekon 2008, 47, 451–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, A.R.; Shively, G.E.; Masters, W.A. Farm productivity and household market participation: Evidence from LSMS data (No. 1005-2016-79000). In Proceedings of the International Association of Agricultural Economists Conference, Beijing, China, 16–22 August 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hlatshwayo, S.I.; Ngidi, M.; Ojo, T.; Modi, A.T.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Slotow, R. A Typology of the Level of Market Participation among Smallholder Farmers in South Africa: Limpopo and Mpumalanga Provinces. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, J.H.; Watson, M.W. Heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors for fixed effects panel data regression. Econometrica 2008, 76, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mirzaei, O.; Micheels, E.T.; Boecker, A. Product and marketing innovation in farm-based businesses: The role of entrepreneurial orientation and market orientation. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2016, 19, 99–130. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A.D. On-farm crop species richness is associated with household diet diversity and quality in subsistence-and market-oriented farming households in Malawi. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muhammad-Lawal, A.; Amolegbe, K.B.; Oloyede, W.O.; Lawal, O.M. Assessment of commercialization of food crops among farming households in Southwestern, Nigeria. Ethiop. J. Environ. Stud. Manag. 2014, 7, 520–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geta, E.; Bogale, A.; Kassa, B.; Elias, E. Productivity and efficiency analysis of smallholder maize producers in Southern Ethiopia. J. Hum. Ecol. 2013, 41, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albizua, A.; Bennett, E.M.; Larocque, G.; Krause, R.W.; Pascual, U. Social networks influence farming practices and agrarian sustainability. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0244619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferede, T.; Gemechu, D. An Econometric Analysis of the Link between Irrigation, Markets and Poverty in Ethiopia: The Case of Smallholder Vegetable and Fruit Production in the North Omo Zone, SNNP Region. 2006. Available online: https://www.gtap.agecon.purdue.edu/resources/download/2504.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- Baiyegunhi, L.J.S.; Fraser, G.C. Smallholder farmers’ access to credit in the Amathole district municipality, eastern Cape Province, South Africa. J. Agric. Rural. Dev. Trop. Subtrop. JARTS 2014, 115, 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Birachi, E.A.; Ochieng, J.; Wozemba, D.; Ruraduma, C.; Niyuhire, M.C.; Ochieng, D. Factors influencing smallholder farmers’ bean production and supply to market in Burundi. Afr. Crop Sci. J. 2011, 19, 335–342. [Google Scholar]

- Owuor, G.; Wangia, S.M.; Onyuma, S.; Mshenga, P.; Gamba, P. Self-Help Groups, A milk supply chain. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2004, 31, 103–121. [Google Scholar]

- McArthur, J.W.; McCord, G.C. Fertilizing growth: Agricultural inputs and their effects in economic development. J. Dev. Econ. 2017, 127, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, D.; Owusu-Sekyere, E.; Owusu, V.; Jordaan, H. Impact of agricultural extension service on adoption of chemical fertilizer: Implications for rice productivity and development in Ghana. NJAS-Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2016, 79, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Chandio, A.A.; Hussain, I.; Jingdong, L. Fertilizer consumption, water availability and credit distribution: Major factors affecting agricultural productivity in Pakistan. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2019, 18, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abokyi, E.; Strijker, D.; Asiedu, K.F.; Daams, M.N. The impact of output price support on smallholder farmers’ income: Evidence from maize farmers in Ghana. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, U.K.; Das, G.; Das, M.; Mathur, T. Small growers’ direct participation in the market and its impact on farm income. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2021, 11, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayi, S.K.; Nkurunziza, J.D. Small holder farmers and sustainable commodity development. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2015, 11, 241–254. [Google Scholar]

| Irrigation Scheme | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Makhathini | 155 | 46.69 |

| Ndumo B | 70 | 21.08 |

| Bululwane | 52 | 15.66 |

| Tugera Ferry | 55 | 16.57 |

| Total | 332 | 100 |

| Variables | Description and Measurement | Mean | Std.Dev | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| * LAND_CABBAGE | Size of land allocated for cabbage production (ha) | 0.55 | 0.85 | 0 | 5 |

| FERTILIZER | Quantity of Basal fertilizer applied (Kg/ha) | 97.26 | 93.16 | 0 | 350 |

| MANURE | Quantity of manure applied (Kg/ha) | 54.53 | 93.92 | 0 | 750 |

| PESTICIDES | Quantity of pesticides applied (Litres/ha) | 7.72 | 21.29 | 0 | 200 |

| LABOUR | Number of labour/ha employed | 17.21 | 28.44 | 0 | 241 |

| AGE | Age of a farmer | 49.40 | 12.51 | 19 | 87 |

| EDUCATION | Education level of a farmer (years) | 4.59 | 4.52 | 0 | 15 |

| HOUSEHOLD_SIZE | Household size (Number of members in the household) | 7.26 | 4.59 | 1 | 38 |

| EXPERIENCE_FARMING | Farmer’s experience in farming (years) | 15.65 | 12.60 | 0 | 59 |

| IRRIGATION_YEARS | Farmer’s experience in irrigation | 9.98 | 10.78 | 0 | 50 |

| DISTANCE_MARKET | Distance from the farm to the market (walking minutes) | 13.28 | 15.84 | 0 | 120 |

| * QUANTITY_CABBAGE | Output produced-quantity of cabbage (Kg) | 4030.50 | 7135.74 | 20 | 8300 |

| QUANTITY_SOLD | Quantity of cabbage sold (Kg) | 3630.47 | 6525.83 | 0 | 51,600 |

| CABBAGE_PRICE | Selling price of cabbage (Rands/Kg) | 4.97 1 | 2.00 | 1.5 | 16.67 |

| ** COMP | Crop output market participation index | 0.83 | 0.25 | 0 | 1 |

| ** MOI | Market orientation index | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0 | 0.43 |

| ** CABBAGE_INCOME | Gross income from selling cabbage (Rands) | 17,668.69 1 | 35,774.36 | 0 | 290,000 |

| Variable | Description | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| GENDER | Farmer gender (1 = Male; 0 = otherwise) | 0.33 | 0.47 |

| TYPES OF IRRIGATION SYSTEMS | Types of irrigation systems used (1 = Sprinkler, 0 = Otherwise) | 0.49 | 0.50 |

| MARITAL STATUS | Farmer’s marital status (1 = Married, 0 = otherwise) | 0.45 | 0.50 |

| MAIN OCCUPATION | Farmer’s main occupation (1 = Full time farmer, 0 = Otherwise) | 0.87 | 0.34 |

| TYPES OF MARKET | Type of the market where the crops are sold (1 = Hawkers, 0 = Otherwise) | 0.33 | 0.47 |

| SOCIAL GRANT | Social grant receiver (1 = Yes, 0 = Otherwise) | 0.83 | 0.37 |

| GROUP MEMBERSHIP | Farmers are members of informal groups (1 = Yes, 0 = No) | 0.55 | 0.50 |

| Variables | Coefficients | Marginal Effects | Robust Std. Err. | t | p > t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production factors | |||||

| FERTILIZER | −0.00002 | −0.00002 | 0.00001 | −1.91 | 0.058 * |

| MANURE | −0.00004 | −0.00004 | 0.00001 | −2.93 | 0.004 ** |

| PESTICIDE | 0.00005 | 0.00005 | 0.00005 | 1.06 | 0.29 |

| NUMBER_OF_LABOUR | −0.00008 | −0.00008 | 0.00005 | −1.54 | 0.125 |

| IRRIGATION_TYPE | 0.00096 | 0.00096 | 0.03170 | 0.03 | 0.976 |

| Socioeconomic factors | |||||

| MARITAL_STATUS | −0.00015 | −0.00015 | 0.03423 | 0 | 0.996 |

| AGE | −0.00091 | −0.00091 | 0.00171 | −0.53 | 0.593 |

| EDUCATION | 0.00033 | 0.00033 | 0.00397 | 0.08 | 0.933 |

| HOUSEHOLD_SIZE | 0.00582 | 0.00582 | 0.00351 | 1.66 | 0.098 * |

| EXPERIENCE_FARMING | −0.00054 | −0.00054 | 0.00170 | −0.32 | 0.752 |

| IRRIGATION_YEARS | 0.00184 | 0.00184 | 0.00172 | 1.07 | 0.287 |

| GENDER | 0.01941 | 0.01941 | 0.03345 | 0.58 | 0.562 |

| Marketing and institutional factors | |||||

| DISTANCE_MARKET | 0.00134 | 0.00134 | 0.00099 | 1.35 | 0.177 |

| CREDIT | 0.02722 | 0.02722 | 0.03313 | 0.82 | 0.412 |

| CABBAGE_SELLING_PRICE | 0.00935 | 0.00935 | 0.00814 | 1.15 | 0.252 |

| GROUP_MEMBERSHIP | −0.03304 | −0.03304 | 0.03219 | −1.03 | 0.306 |

| SOCIAL GRANT | −0.02455 | −0.02455 | 0.04292 | −0.57 | 0.568 |

| MARKET_TYPE | −0.02630 | −0.02630 | 0.03395 | −0.77 | 0.439 |

| _cons | 0.83501 | 0.11130 | 7.5 | 0.000 | |

| Number of obs | 327 | ||||

| LR chi2(18) | 40.82 | ||||

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0016 | ||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.1776 | ||||

| Log-likelihood | −94.477 |

| Variables | Coefficients | Marginal Effects | Robust Std. Err. | T | p > t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production factors | |||||

| FERTILIZER | −0.00003 | −0.00003 | 0.00001 | −2.680 | 0.008 ** |

| MANURE | −0.00004 | −0.00004 | 0.00002 | −2.480 | 0.014 ** |

| PESTICIDE | −0.00001 | −0.00001 | 0.00006 | −0.230 | 0.818 |

| NUMBER_OF_LABOUR | −0.00021 | −0.00021 | 0.00007 | −3.280 | 0.001 *** |

| IRRIGATION_TYPE | 0.00260 | 0.00260 | 0.03729 | 0.070 | 0.944 |

| Socioeconomic factors | |||||

| MARITAL_STATUS | −0.00774 | −0.00774 | 0.04005 | −0.190 | 0.847 |

| AGE | −0.00048 | −0.00048 | 0.00198 | −0.240 | 0.810 |

| EDUCATION | 0.00895 | 0.00895 | 0.00461 | 1.940 | 0.053 * |

| HOUSEHOLD_SIZE | 0.00774 | 0.00774 | 0.00400 | 1.940 | 0.054 * |

| EXPERIENCE_FARMING | 0.00439 | 0.00439 | 0.00199 | 2.200 | 0.028 ** |

| IRRIGATION_YEARS | −0.00335 | −0.00335 | 0.00202 | −1.660 | 0.099 * |

| GENDER | 0.03434 | 0.03434 | 0.03921 | 0.880 | 0.382 |

| Marketing and institutional factors | |||||

| DISTANCE_MARKET | −0.00014 | −0.00014 | 0.00116 | −0.120 | 0.903 |

| CREDIT | 0.08691 | 0.08691 | 0.03874 | 2.240 | 0.026 ** |

| CABBAGE_SELLING_PRICE | −0.01081 | −0.01081 | 0.00931 | −1.160 | 0.246 |

| GROUP_MEMBERSHIP | 0.07839 | 0.07839 | 0.03776 | 2.080 | 0.039 ** |

| SOCIAL GRANT | −0.04846 | −0.04846 | 0.05009 | −0.970 | 0.334 |

| MARKET_TYPE | −0.05325 | −0.05325 | 0.03961 | −1.340 | 0.180 |

| _cons | 0.35368 | 0.12919 | 2.740 | 0.007 | |

| Number of obs | 327 | ||||

| LR chi2(18) | 74.55 | ||||

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0000 | ||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.2374 | ||||

| Log-likelihood | −119.71651 |

| Variables | Coefficients | Std. Err. | t | p > t |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production factors | ||||

| COMP | 12.8158 | 7.0627 | 1.81 | 0.071 * |

| MOI | −8.7424 | 5.3420 | −1.64 | 0.103 |

| FERTILIZER | −0.0007 | 0.0008 | −0.82 | 0.412 |

| MANURE | 0.0041 | 0.0013 | 3.07 | 0.002 ** |

| PESTICIDE | 0.0427 | 0.0051 | 8.35 | 0.000 *** |

| NUMBER_OF_LABOUR | 0.0231 | 0.0056 | 4.13 | 0.000 *** |

| IRRIGATION_TYPE | 0.3970 | 3.3375 | 0.12 | 0.905 |

| Socioeconomic factors | ||||

| MARITAL_STATUS | 0.8598 | 3.5951 | 0.24 | 0.811 |

| AGE | 0.1027 | 0.1788 | 0.57 | 0.566 |

| EDUCATION | 0.1218 | 0.4172 | 0.29 | 0.771 |

| HOUSEHOLD_SIZE | 0.1739 | 0.3650 | 0.48 | 0.634 |

| EXPERIENCE_FARMING | −0.2030 | 0.1800 | −1.13 | 0.26 |

| IRRIGATION_YEARS | −0.1778 | 0.1826 | −0.97 | 0.331 |

| GENDER | −0.9634 | 3.5307 | −0.27 | 0.785 |

| Marketing and Institutional factors | ||||

| DISTANCE_MARKET | −0.0031 | 0.1052 | −0.03 | 0.977 |

| CREDIT | −1.5523 | 3.5104 | −0.44 | 0.659 |

| CABBAGE_SELLING_PRICE | 2.0947 | 0.8432 | 2.48 | 0.014 ** |

| GROUP_MEMBERSHIP | 0.9731 | 3.4361 | 0.28 | 0.777 |

| SOCIAL GRANT | −2.113168 | 4.54097 | −0.47 | 0.642 |

| MARKET_TYPE | 0.948109 | 3.579589 | 0.26 | 0.791 |

| _cons | 2.039741 | 13.00145 | 0.16 | 0.875 |

| Number of obs | 327 | |||

| F(20, 306) | 7.82 | |||

| R-squared | 0.3382 | |||

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.2950 | |||

| Root MSE | 29.165 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mkuna, E.; Wale, E. Explaining Farmers’ Income via Market Orientation and Participation: Evidence from KwaZulu-Natal (South Africa). Sustainability 2022, 14, 14197. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114197

Mkuna E, Wale E. Explaining Farmers’ Income via Market Orientation and Participation: Evidence from KwaZulu-Natal (South Africa). Sustainability. 2022; 14(21):14197. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114197

Chicago/Turabian StyleMkuna, Eliaza, and Edilegnaw Wale. 2022. "Explaining Farmers’ Income via Market Orientation and Participation: Evidence from KwaZulu-Natal (South Africa)" Sustainability 14, no. 21: 14197. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114197

APA StyleMkuna, E., & Wale, E. (2022). Explaining Farmers’ Income via Market Orientation and Participation: Evidence from KwaZulu-Natal (South Africa). Sustainability, 14(21), 14197. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114197