A Systematic Review of the Delphi–AHP Method in Analyzing Challenges to Public-Sector Project Procurement and the Supply Chain: A Developing Country’s Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Project Procurement Management

2.2. Project Supply Chain Management

2.3. Challenges to Public Sector Development Projects in Bangladesh

2.4. Sustainable Development: Public Sector Project Procurement and Supply Chain Management

3. Methodology and Data Collection

3.1. MCDM: Delphi and AHP Techniques

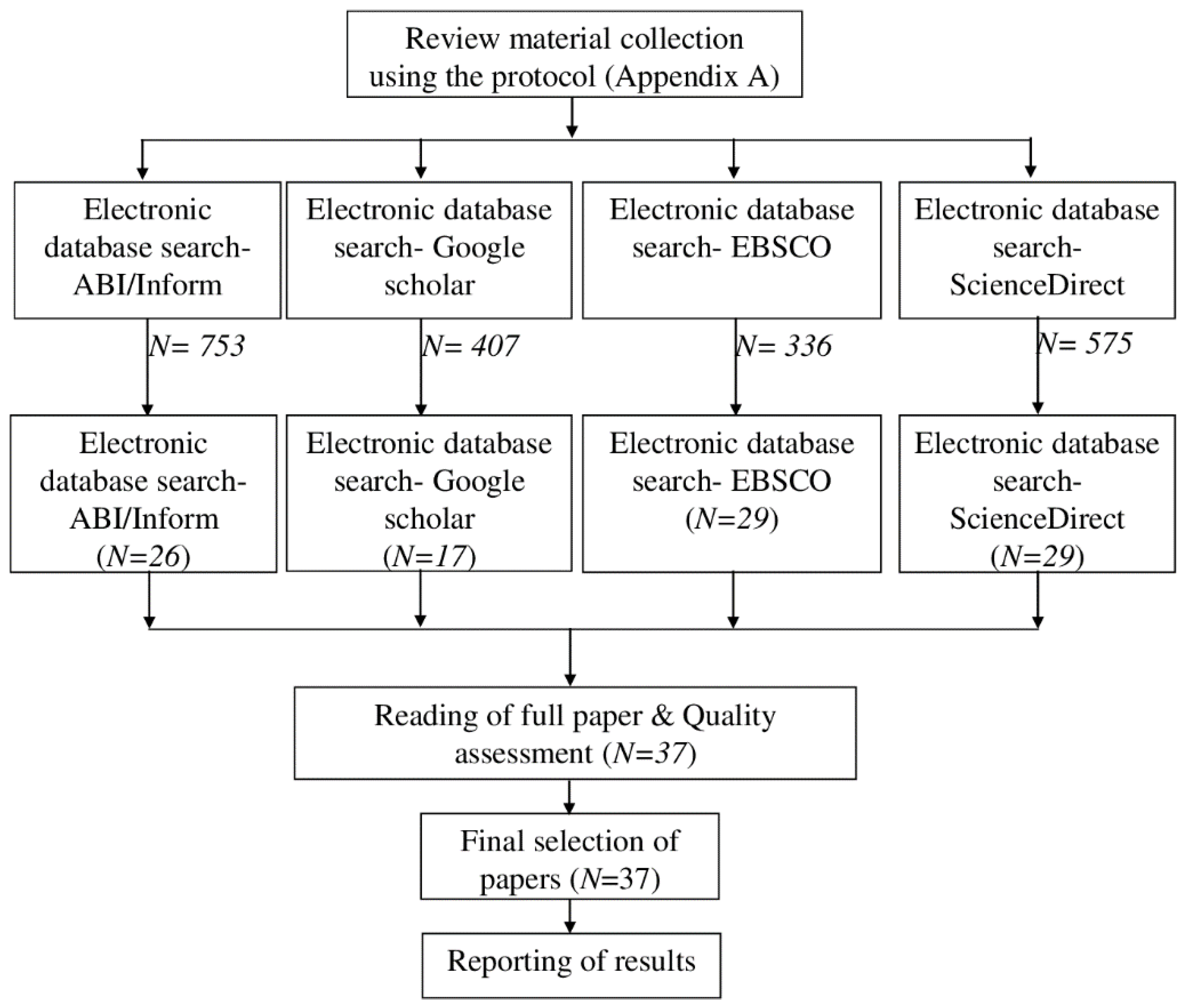

3.2. Systematic Review

3.2.1. Stage 1: Review Planning as Highlighted Earlier, the Aim of This Study Is to Review the Literature on the Delphi–AHP Method to Address the following Two Questions

3.2.2. Stage 2: Conducting the Review

3.2.3. Stage 3: Reporting and Dissemination

4. Result and Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

4.2. Relative Strengths and Limitations of the Delphi and/or AHP Method

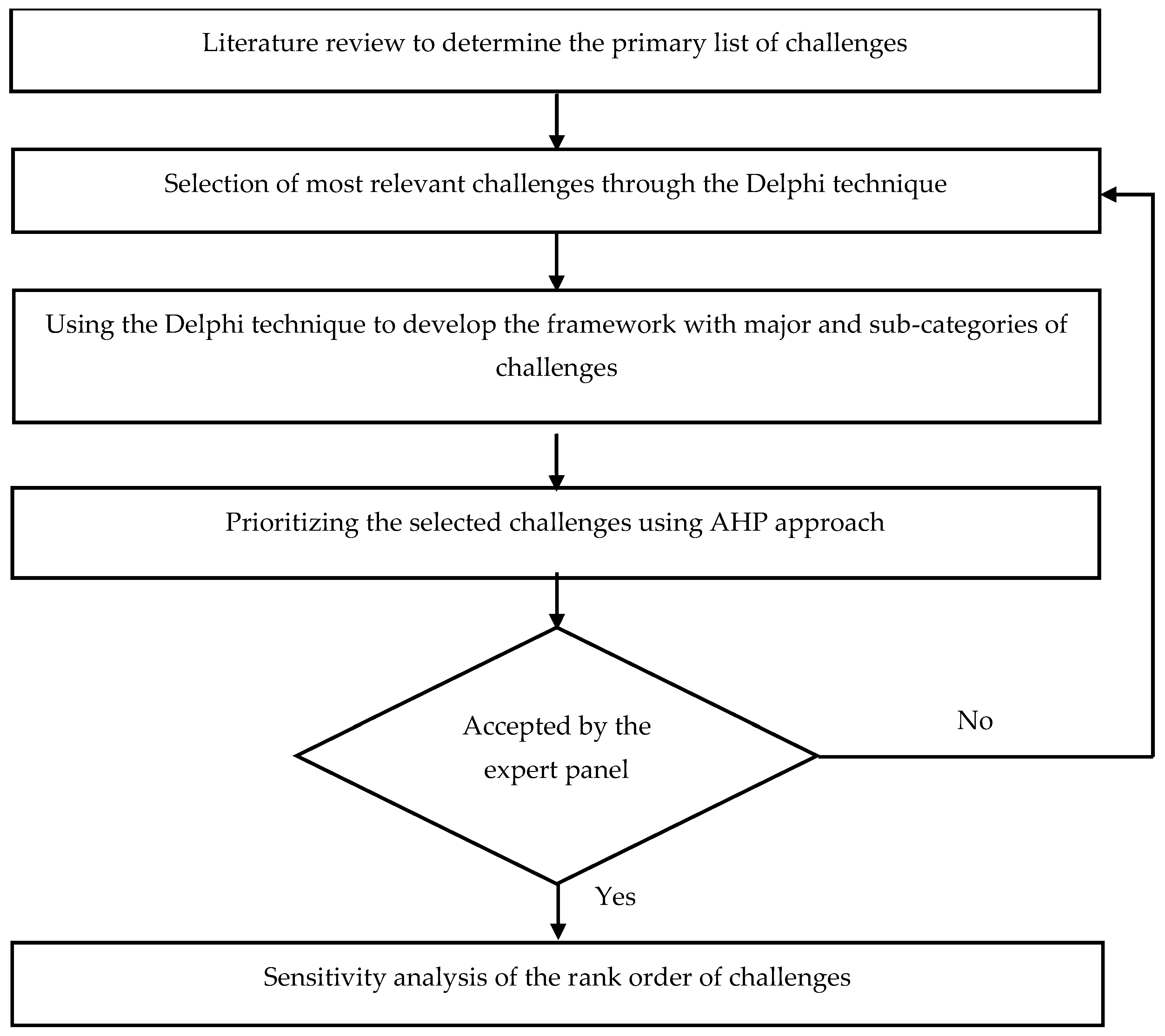

4.3. Best-Practice Approach: Best-Practice Framework using Delphi–AHP Method

4.3.1. Step I: Literature Review to Determine the Primary List of Challenges

4.3.2. Step II: Selection of Most Relevant Challenges through the Delphi Technique Using Semi-Structured Questionnaire and Experts’ Opinion

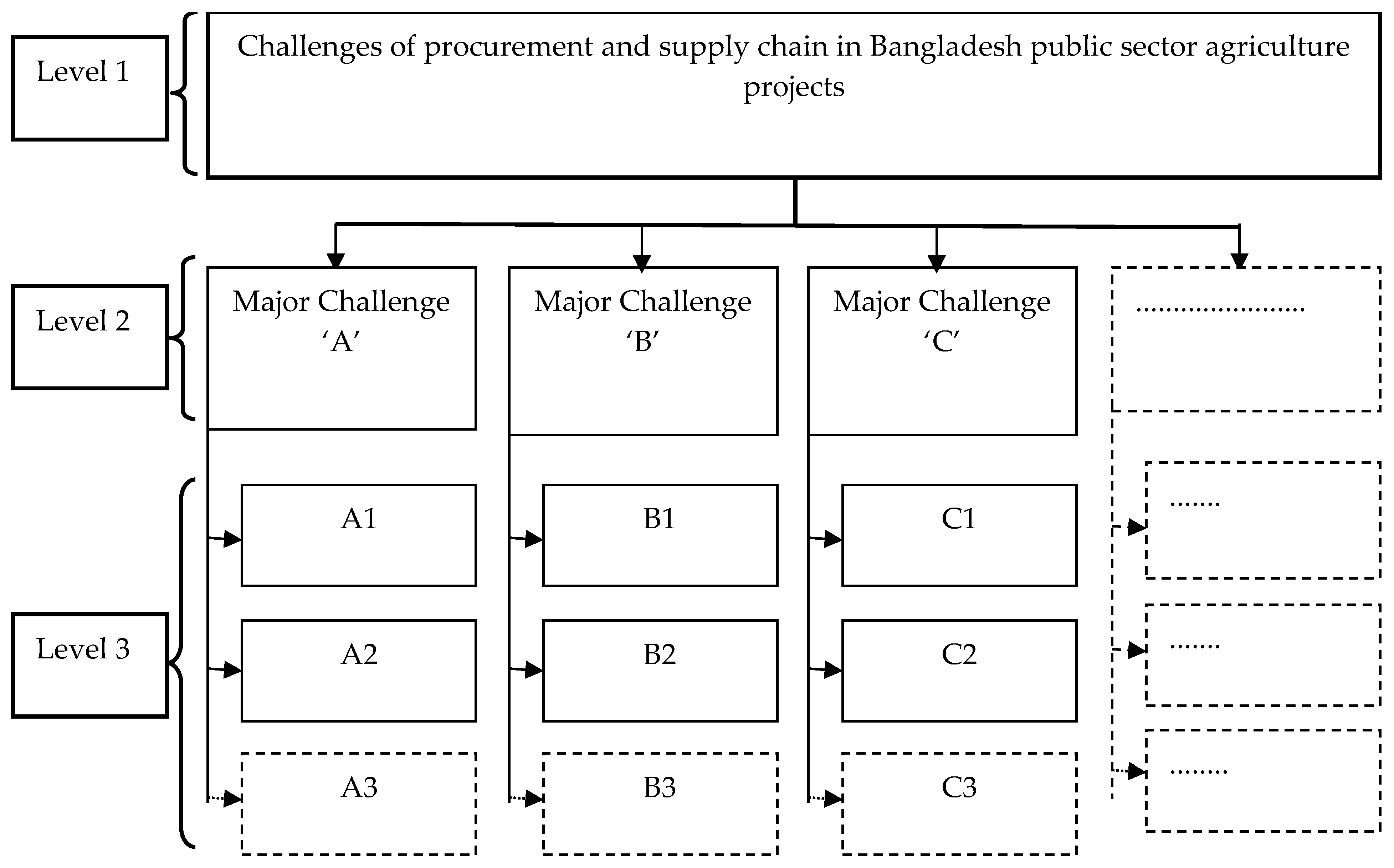

4.3.3. Step III: Development of the Framework having Major and Sub-Categories of Challenges for AHP Analysis

4.3.4. Step IV: Prioritizing the Selected Challenges Using the AHP Approach

4.3.5. Step V: Sensitivity Analysis of the Rank Order of the Challenges

4.4. Contribution of the Research Findings

- Because no substantial research has been found on the application of the Delphi and AHP method in analyzing supply chain challenges issues of public sector development projects in a developing country context, the review findings would directly contribute to the existing literature on the methodology and supply chain context. Furthermore, the study recommended a best-practice research framework along with a detailed process description based on the existing literature review. Additionally, the study also reveals some disadvantages of these tools, and it also proposes some other alternative tools (i.e., Delphi and BWM instead of Delph and AHP). Consequently, the findings would also be very useful in future research decision-making when selecting analytical tools for such research.

- Professionals involved in the planning and management of similar types of projects would greatly benefit from the methodological framework in analyzing the challenges of development project procurement and supply chain issues in a developing country context. Furthermore, because developing countries have limited resources to implement development projects, this analytical tool would be invaluable in practitioners’ decision-making processes to address the most pressing challenges more effectively while ensuring value for money.

- Furthermore, the finding has some indirect impact on society as well. One of the key objectives of the review is to identify whether the Delph and AHP methods would be applicable for analyzing procurement and supply chain challenges of public sector agriculture projects or not. According to the finding, the tools have been identified as one of the most effective tools for conducting such research activities. Such specific review findings will assist not only researchers or academics but also professionals in identifying key challenges to public sector development projects initiated for the countries’ sustainable agricultural development. As a result, the discovery will have an indirect impact on agricultural development, which will benefit social development as well.

- Finally, policymakers involved in making policies for project supply chain management approaches and challenges mitigating approaches can also benefit from these analytical tools in order to better understand the critical challenges to the project procurement and supply chain and, thus, carry out more successful agricultural development projects.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Objectives of the study: | Refer to Section 1 (Introduction). |

| Research questions: | Refer to Section 3.2.1. |

| Strategy to identify studies: | Development of the search strings (Table 1). |

| Searching of ABI/Inform, EBSCO, Google Scholar (GS), ScienceDirect databases. | |

| Search on 18-year period (2000–2019). | |

| Selection of the studies: | Selection criteria 1: titles and abstracts screening; |

| Selection criteria 2: introduction, methodology, conclusion and looking over the paper’s content. | |

| Selection criteria 3: assessment about the quality of journals (scholarly and peer-reviewed journals), accessibility (English language papers), theoretical (Delphi or AHP method in identifying challenges to procurement and/or supply chain management in public sector agriculture project in developing countries) and empirical content (qualitative) and unit of analysis (research methodology along with the analytical tools). | |

| Selection criteria 4: quality appraisal of papers. Papers should be assessed according to its argument, contribution, theoretical bases and methodological rigor. | |

| Data extraction and monitoring process: | Reading of full papers focusing on the methodology; Identification of informational contents with respect to research questions. |

| Data analysis and synthesis: | Descriptive content analysis by crossing data from different concepts and literature. |

| Answering research questions from what is already answered in the literature. |

Appendix B

| Methods | Reference |

|---|---|

| Literature review (LR) + Delphi | [67,82,83] |

| Literature review + Delphi + AHP | [20,93] |

| Literature review + AHP | [7,54,58,81] |

| Literature review + Survey + AHP | [61] |

| Literature review + Expert opinion + AHP | [42,71,80,84,114] |

| Case study + AHP | [55,60,78] |

| Case study + SCOR-FAHP | [65] |

| Literature review + Fuzzy Delphi + AHP | [18] |

| Literature review + Expert opinion + Fuzzy AHP | [59,64,73,74] |

| Literature review + Expert opinion + AHP + Fuzzy AHP | [68] |

| Literature review + Expert opinion + Fuzzy Delphi + Fuzzy AHP | [72] |

| Literature review + Expert opinion + Fuzzy Delphi + BWM | [76] |

| Literature review + AHP + TOPSIS | [70] |

| Literature review + Hybrid AHP + Fuzzy TOPSIS/PROMETHEE/Diagraph and Matrix | [79] |

| Case + Fuzzy AHP + Fuzzy TOPSIS | [75] |

| Case + Literature review + Fuzzy AHP + Fuzzy TOPSIS | [62] |

| Expert opinion + Fuzzy AHP + Fuzzy TOPSIS | [66] |

| Survey + Fuzzy AHP + Fuzzy TOPSIS | [77] |

| Literature review + Expert opinion + AHP + SAW | [63] |

| Literature review + Expert opinion + AHP+ DEMATEL | [69] |

| Literature review + AHP-integrated QFD approach | [56] |

| Literature review + OM-AHP | [57] |

References

- Jum’a, L.; Zimon, D.; Ikram, M. A relationship between supply chain practices, environmental sustainability and financial performance: Evidence from manufacturing Companies in Jordan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.R.; Alam, M.J.; Tabassum, N.; Burton, M.; Khan, N.A. Investigating supply chain challenges of public sector agriculture development projects in Bangladesh: An application of modified Delphi-BWM-ISM approach. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, B.; Debnath, A.; Chiu, A.S.F.; Ahmed, W. Circular economy-driven two-stage supply chain management for nullifying waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 339, 130513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, P.; Maffioli, A.; Salazar, L. Introduction to the special feature: Evaluating the impact of agricultural projects in developing countries. J. Agric. Econ. 2011, 62, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, J.D.B.; Reidsma, P.; Giller, K.; Todman, L.; Whitmore, A.; van Ittersum, M. Sustainable development goal 2: Improved targets and indicators for agriculture and food security. Ambio 2019, 48, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addo-Duah, P.; Westcott, T.; Mason, J.; Booth, C.; Mahamadu, A.M. Developing capability of public sector procurement in Ghana: An assessment of the road subsector client. Constr. Res. Congr. 2014, 2053–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ahsan, K.; Paul, S.K. Procurement issues in donor-funded international development projects. J. Manag. Eng. 2018, 34, 04018041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasik, S. Are public projects different than projects in other sectors? preliminary results of empirical research. Procedia. Comput. Sci. 2016, 100, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golini, R.; Kalchschmidt, M.; Landoni, P. Adoption of project management practices: The impact on international development projects of non-governmental organizations. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 650–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, K. Determinants of the performance of public sector development projects. Int. J. Manag. 2012, 29, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, G.Y.; Al-Mharmah, H.A. Project management practice by the public sector in a developing country. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2000, 18, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, K.; Gunawan, I. Analysis of cost and schedule performance of international development projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2010, 28, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damoah, I.S.; Akwei, C.A.; Oduro Amoako, I.; Botchie, D. Corruption as a source of government project failure in developing countries: Evidence from Ghana. Proj. Manag. J. 2018, 49, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A. Public procurement and corruption in bangladesh confronting the challenges and opportunities. J. Public Adm. Policy Res. 2010, 2, 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Planning Commission (PC). The 7th Five Year Plan (FY 2016-FY2020). 2015. Available online: https://www.plancomm.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/plancomm.portal.gov.bd/files/aee61c03_3c11_4e89_9f30_d79639595c67/7th_FYP_18_02_2016.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Hossain, M. Sustainable Procurement Is the Agenda. 2018. Available online: Cptu.gov.bd/upload/publication/2018-08-16-15-45-40-Newsletter-CPTU-July-2018.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2020).

- Ministry of Agriculture (MoA). Seventh Five Year Plan (7FYP). 2016. Available online: https://moa.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/moa.portal.gov.bd/policies/f2005dba_0b1c_4d25_a4dd_e2e0f3b53ee7/Seventh_FYP_MoA.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Bouzon, M.; Govindan, K.; Rodriguez, C.M.T.; Campos, L.M.S. Identification and analysis of reverse logistics barriers using Fuzzy Delphi Method and AHP. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 108, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.; Lin, F. Developing a decision model for brand naming using Delphi method and Analytic Hierarchy Process. Asis Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2013, 25, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moktadir, M.; Ali, S.M.; Mangla, S.K.; Sharmy, T.A.; Luthra, S.; Mishra, N.; Garza-Reyes, J.A. Decision modeling of risks in pharmaceutical supply chains. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2018, 118, 1388–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, M.E. Procurement: Process overview and emerging project management techniques. Chapter Eleven; In The Wiley Guide to Project Technology, Supply Chain & Procurement Management; Morris, P., Pinto, J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, J. Benchmarking in public procurement. Benchmarking Int. J. 2008, 15, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlinson, S.; Walker, D. Culture and its impact upon project procurement. In Procurement Systems: A Cross-Industry Project Management Perspective, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2007; Chapter 8; pp. 301–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PMI. PMBOK Guide|Project Management Institute. PMBOK Guide. 2017. Available online: https://www.pmi.org/pmbok-guide-standards/foundational/PMBOK (accessed on 16 April 2022).

- Handfield, R.; Nichols, J.E.L. Supply Chain Redesign: Transforming Supply Chains into Integrated Value Systems; Ft Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chattered Institute of Procurement and Supply (CIPS). Scope and Influence of Procurement and Supply; The Chartered Institute of Procurement & Supply (CIPS): Stamford, UK, 2019; PE9 3NZ; ISBN 978-1-86124-288-4. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP). Supply Chain Management Terms and Glossary. 2013. Available online: https://cscmp.org/CSCMP/Educate/SCM_Definitions_and_Glossary_of_Terms.aspx (accessed on 23 September 2022).

- Basu, R.; Wright, J.N. Managing Global Supply Chains, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvez, M. Analyzing Public Procurement Process Operational Inefficiencies in Bangladesh: A Study on Department of Public Health Engineering (dphe). Ph.D. Thesis, BRAC University, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank (WB). An Overview of the World Bank Group’s Work in Bangladesh. 2017. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/bangladesh (accessed on 22 October 2017).

- Hamiduzzaman, M. Planning and managing of development projects in Bangladesh: Future challenges for government and private organizations. J. Public Adm. Policy Res. 2014, 6, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- IMED. Project Completion Report. Implementation Monitoring and Evaluation Division (IMED), Bangladesh. 2020. Available online: https://imed.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/imed.portal.gov.bd/page/315d64be_c080_478a_8b14_fddea2e03f02/MinofAgriculture_23_5_20191.docx (accessed on 29 August 2020).

- Lysenko-Ryba, K.; Zimon, D. Customer behavioral reactions to negative experiences during the product return. Sustainability 2021, 13, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, S.R. Utilizing and adapting the Delphi method for use in qualitative research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2015, 14, 1609406915621381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Jang, Y.C. Application of Delphi-AHP methods to select the priorities of weee for recycling in a waste management decision-making tool. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 128, 941–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moktadir, M.A.; Ali, S.M.; Kusi-Sarpong, S.; Shaikh, M.A.A. Assessing challenges for implementing industry 4.0: Implications for process safety and environmental protection. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2018, 117, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.; Sandford, B. The Delphi technique: Making sense of consensus. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2007, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.Y.; Huang, C.Y.; Huang, C.J. The application of modified Delphi method and AHP to analyze the influential factors of leading vegetarianism trends in Taiwan. IJRRAS 2016, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Taleai, M.; Nasir, K.; Mansourian, A. Using Delphi-AHP method to survey major factors causing urban plan implementation failure. Artic. J. Appl. Sci. 2008, 8, 2746–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Sutherland, J.W. Development of multi-criteria decision-making model for remanufacturing technology portfolio selection. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1939–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.K.; Cheffi, W. Green supply chain performance measurement using the analytic hierarchy process: A comparative analysis of manufacturing organisations. Prod. Plan. Control. 2013, 24, 702–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Kaliyan, M.; Kannan, D.; Haq, A.N. Barriers analysis for green supply chain management implementation in Indian industries using Analytic Hierarchy Process. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 147, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaan, J.; Mangla, S. Decision Modeling Approach for Eco-Driven Flexible Green Supply Chain. In Systemic Flexibility and Business Agility; Sushil, Chroust, G., Eds.; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2015; pp. 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T. The Analytic Hierarchy Process: Planning, Priority Setting, Resource Allocation; RWS Publications: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, C.R.; Christopher, M.; Lago Da Silva, A. Achieving supply chain resilience: The role of procurement. Supply Chain. Manag. 2014, 19, 626–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Marcos, J.; Burr, M. Co-producing management knowledge. Manag. Decis. 2004, 42, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brereton, P.; Kitchenham, B.; Budgen, D.; Turner, M.; Khalil, M. Lessons from applying the systematic literature review process within the software engineering domain. J. Syst. Softw. 2007, 80, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoli, C.; Schabram, K. A Guide to Conducting a Systematic Literature Review of Information Systems Research. Sprouts Work. Pap. Inf. Syst. 2010, 10, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. guidance on conducting a systematic literature review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S.; Gold, S. Conducting content-analysis based literature reviews in supply chain management. Supply Chain. Manag. 2012, 17, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Collins, A.M.; Coughlin, D.; Kirk, S. The role of Google Scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.; Huberman, A. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ahsan, K.; Rahman, S. Green public procurement implementation challenges in Australian public healthcare sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 100, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, R.J.; Subramanian, N.; Gunasekaran, A.; Palaniappan, P.L.K. Influence of non-price and environmental sustainability factors on truckload procurement process. Ann. Oper. Res. 2017, 250, 363–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.M.H.; Umme, N.J.; Nuruzzaman, M. Strategies for mitigating supply-side barriers in the apparel supply chain: A study on the apparel industry of Bangladesh. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2018, 19, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Cooper, O. An orders-of-magnitude AHP supply chain risk assessment framework. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 182, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enyinda, C.; Gebremikael, F.; Ogbuehi, A.O. An analytical model for healthcare supply chain risk management. Afr. J. Bus. Econ. Res. 2014, 9, 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly, K.K.; Guin, K.K. A Fuzzy AHP approach for inbound supply risk assessment. Benchmarking 2013, 20, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudenzi, B.; Borghesi, A. Managing risks in the supply chain using the AHP method. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2006, 17, 114–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadge, A.; Kaklamanou, M.; Choudhary, S.; Bourlakis, M. Implementing environmental practices within the Greek dairy supply chain drivers and barriers for SMEs. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 1995–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, S.S.; Khanbabaei, M.; Sabzehparvar, M. A model for supply chain risk management in the automotive industry using Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process and Fuzzy TOPSIS. Benchmarking 2018, 25, 3831–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaberidoost, M.; Olfat, L.; Hosseini, A.; Kebriaeezadeh, A.; Abdollahi, M.; Alaeddini, M.; Dinarvand, R. Pharmaceutical supply chain risk assessment in Iran using Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and Simple Additive Weighting (SAW) methods. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2015, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakhar, M.; Srivastava, M.K. Prioritization of drivers, enablers and resistors of agri-logistics in an emerging economy using Fuzzy AHP. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 2166–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Li, J.; Shen, S. Supply chain risk assessment and control of port enterprises: Qingdao port as case study. Asian J. Shipp. Logist. 2018, 34, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabra, G.; Ramesh, A. Analyzing drivers and barriers of coordination in humanitarian supply chain management under fuzzy environment. Benchmarking 2015, 22, 559–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kembro, J.; Näslund, D.; Olhager, J. Information sharing across multiple supply chain tiers: A Delphi study on antecedents. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 193, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kansara, S. Information technology barriers in Indian sugar supply chain: An AHP and Fuzzy AHP approach. Benchmarking 2018, 25, 1978–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangla, S.K.; Govindan, K.; Luthra, S. Critical success factors for reverse logistics in Indian industries: A structural model. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 129, 608–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.; Chen, J.; Liu, T. Response to demand uncertainty of supply chains: A value-focused approach with AHP and TOPSIS. Int. J. Ind. Eng. 2018, 25, 739–756. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Luthra, S.; Haleem, A. Benchmarking supply chains by analyzing technology transfer critical barriers using AHP approach. Benchmarking 2015, 22, 538–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Mangla, S.K.; Agrawal, V.; Sharma, K.; Gupta, D. When risks need attention: Adoption of green supply chain initiatives in the pharmaceutical industry. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 3554–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangla, S.K.; Kumar, P.; Barua, M.K. Risk analysis in green supply chain using Fuzzy AHP approach: A case study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 104, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangla, S.; Govindan, K.; Luthra, S. Prioritizing the barriers to achieve sustainable consumption and production trends in supply chains using Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 151, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazam, M.; Xu, J.; Tao, Z.; Ahmad, J.; Hashim, M. A Fuzzy AHP-TOPSIS framework for the risk assessment of green supply chain implementation in the textile industry. Int. J. Supply Oper. Manag. 2015, 2, 548–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebi, I.; Arab, A.; Moghadam, M. Analyzing the barriers to humanitarian supply chain management: A case study of the Tehran Red Crescent Societies. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 24, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samvedi, A.; Jain, V.; Chan, F.T.S. Quantifying risks in a supply chain through integration of Fuzzy AHP and Fuzzy TOPSIS. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2013, 51, 2433–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenherr, T.; Tummala, V.; Harrison, T. Assessing supply chain risks with the Analytic Hierarchy Process: Providing decision support for the offshoring decision by a US manufacturing company. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2008, 14, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthil, S.; Murugananthan, K.; Ramesh, A. Analysis and prioritisation of risks in a reverse logistics network using hybrid multi-criteria decision-making methods. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 179, 716–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Bhat, A. Identification and assessment of supply chain risk: Development of AHP model for supply chain risk prioritisation. Int. J. Agil. Syst. Manag. 2012, 5, 350–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K. Prioritizing the factors for coordinated supply chain using Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). Meas. Bus. Excell. 2013, 17, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabish, S.Z.S.; Jha, K.N. Analyses and evaluation of irregularities in public procurement in India. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2011, 29, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, M.A.; Handayani, N.U.; Mustikasari, A. Factors for implementing green supply chain management in the construction industry. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2018, 11, 651–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Blackhurst, J.; Chidambaram, V. A model for inbound supply risk analysis. Comput. Ind. 2006, 57, 350–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffie, N.A.M.; Shukor, N.A.M.; Rasmani, K.A. Fuzzy Delphi Method: Issues and challenges. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Logistics, Informatics and Service Sciences, LISS 2016, Sydney, Australia, 24–27 July 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, S.; Govindan, K.; Kannan, D.; Mangla, S.K.; Garg, C.P. An integrated framework for sustainable supplier selection and evaluation in supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 1686–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. There is no mathematical validity for using fuzzy number crunching in the Analytic Hierarchy Process. J. Syst. Sci. Syst. Eng. 2006, 15, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, J. Best-Worst multi-criteria decision-making method. Omega 2015, 53, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadjadi, S.J.; Karimi, M. Best-Worst multi-criteria decision-making method: A robust approach. Decis. Sci. Lett. 2018, 7, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, X.; Tang, M.; Liao, H.; Shen, W.; Lev, B. The state-of-the-art survey on integrations and applications of the Best Worst Method in decision making: Why, what, what for and what’s next? Omega 2019, 87, 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameyaw, E.; Hu, Y.; Shan, M.; Chan, A.P.C.; Le, Y. Application of Delphi Method in Construction Engineering and Management Research: A Quantitative Perspective. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2016, 22, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. How to make a decision: The Analytic Hierarchy Process. Inf. J. Appl. Anal. 1994, 24, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moktadir, M.; Ali, S.; Paul, S.; Shukla, N. Barriers to big data analytics in manufacturing supply chains: A case study from Bangladesh. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 128, 1063–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusworth, J.W.; Franks, T.R. Managing Projects in Developing Countries; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twose, P.; Jones, U.; Cornell, G. Minimum standards of clinical practice for physiotherapists working in critical care settings in the United Kingdom: A Modified Delphi Technique. J. Intensive Care Soc. 2018, 20, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasson, F.; Keeney, S. Enhancing rigour in the Delphi technique research. Technol. Forecast. Soc Chang. 2011, 78, 1695–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeney, S. The Delphi Technique. In The Research Process in Nursing; Gerrish, K., Anne, L., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, Y.; Wang, S.; Chan, A.P.C.; Cheung, E. Understanding the risks in China’s PPP projects: Ranking of their probability and consequence. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2011, 18, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon, C.K.H.; Chan, A.P.C.; Yam, M.C.H. Empirical study to investigate the difficulties of implementing safety practices in the repair and maintenance sector in Hong Kong. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2012, 138, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.P.C.; Yung, E.H.K.; Lam, P.T.I.; Tam, C.M.; Cheung, S.O. Application of Delphi method in selection of procurement systems for construction projects. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2001, 19, 699–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Ross, S. Sport sponsorship decision making in a global market: An approach of Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). Sport Bus. Manag. 2012, 2, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambasivan, M.; Fei, N. Evaluation of critical success factors of implementation of iso 14001 using Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP): A case study from Malaysia. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1424–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoli, C.; Pawlowski, S.D. The Delphi method as a research tool: An example, design considerations and applications. Inf. Manag. 2004, 42, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avella, J.R. Delphi panels: Research design, procedures, advantages, and challenges. Int. J. Dr. Stud. 2016, 11, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, E.W.; Li, H. Information Priority-Setting for Better Resource Allocation Using Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). Inf. Manag. Comput. Secur. 2001, 9, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Rank from comparisons and from ratings in the Analytic Hierarchy/Network Processes. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2006, 168, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. An exposition of the AHP in reply to the paper “remarks on the Analytic Hierarchy Process”. Manag. Sci. 1990, 36, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. What is relative measurement? the ratio scale phantom. Math. Comput. Model. 1993, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.; Kearns, K. Analytical Planning: The Organization of Systems; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, E.; Pereyra-Rojas, M. Understanding the Analytic Hierarchy Process. In Practical Decision Making; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, M.; Braglia, M. The Analytic Hierarchy Process applied to maintenance strategy selection. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2000, 70, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananda, J.; Herath, G. The use of Analytic Hierarchy Process to incorporate stakeholder preferences into regional forest planning. For. Policy Econ. 2003, 5, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.; Sharma, M.K. Multi-criteria supplier selection model using the Analytic Hierarchy Process approach. J. Model. Manag. 2016, 11, 326–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, S.; Mangla, S.; Xu, L.; Diabat, A. Using AHP to evaluate barriers in adopting sustainable consumption and production initiatives in a supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 181, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search Strings | Primary Selection | First Selection | Second Selection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (Procurement OR purchase) AND (“supply chain*”) AND (challenge OR barrier) AND (“Delphi method*” OR “AHP method*”) | 1141 | 52 | 13 |

| 2 | (“Delphi method*” OR “AHP method*”) AND (procurement* OR “supply chain*”) AND (challenge* OR factor*) AND (“developing countries*”) | 560 | 16 | 5 |

| 3 | (“Delphi method*” OR “AHP method*”) AND (procurement* OR “supply chain*”) AND (challenge* OR factor*) AND (“public project*”) AND (“developing countries*”) | 225 | 20 | 5 |

| 4 | (“Delphi method*” OR “AHP method*”) AND (procurement* OR “supply chain*”) AND (challenge* OR factor*) AND (“public project*”) AND (agriculture*) AND (“developing countries*”) | 145 | 13 | 6 |

| (a) Primary Search | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| String (ST) | Primary Search | |||

| ABI | GS | EBSCO | Science Direct | |

| ST-1 | 420 | 369 | 3 | 349 |

| ST-2 | 327 | 10 | 2 | 221 |

| ST-3 | 5 | 21 | 195 | 4 |

| ST-4 | 1 | 7 | 136 | 01 |

| Total: | Primary search = 2071 | |||

| (b) First Selection | ||||

| String (ST) | First Selection | String (ST) | First Selection | |

| ABI | ABI | |||

| ST-1 | 16 | 12 | 0 | |

| ST-2 | 9 | 1 | 1 | |

| ST-3 | 1 | 2 | 17 | |

| ST-4 | 0 | 2 | 11 | |

| Total: | First selection = 101 | |||

| (c) Second Selection | ||||

| String (ST) | Second Selection | String (ST) | Second Selection | |

| ABI | ABI | |||

| ST-1 | 6 | 7 | 0 | |

| ST-2 | 4 | 0 | 1 | |

| ST-3 | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| ST-4 | 0 | 2 | 4 | |

| Total: | Second selection = 37 | |||

| References | Challenges/Factors/Risks | Procurement/Supply Chain | Industry/Sector/Project | Study Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [54] | Challenges | Green procurement | Public healthcare | Australia |

| [7] | Challenges | Procurement | ID public projects | Bangladesh |

| [55] | Factors | Procurement | Automotive and logistic | Not specified |

| [18] | Barriers | Reverse logistics | Electrical–electronic | Brazil |

| [56] | Barriers | Supply chain | Apparel | Bangladesh |

| [57] | Risks | Supply chain | Telecom | China |

| [58] | Risks | Supply chain | Healthcare | Nigeria |

| [59] | Risks | Inbound supply chain management | Not specified | Not specified |

| [60] | Risks | Supply chain | Not specified | Not specified |

| [61] | Barriers | Food supply chain | Dairy Food | Greece |

| [42] | Barrier | Green supply chain | Manufacturing | India |

| [62] | Risks | Supply chain | Automotive | Iran |

| [63] | Risks | Supply chain | Pharmaceutical | Iran |

| [64] | Driver, enabler, and resistor | Logistics | Agri-logistic | India |

| [65] | Risks | Supply chain | Coastal port | China |

| [66] | Barriers | Supply chain management | Humanitarian | India |

| [67] | Factors | Supply chain | Global supply chain information sharing | Not specified |

| [68] | Barriers | Supply chain | Sugar manufacturing | India |

| [69] | Barriers | Supply chain | Plastic manufacturing | India |

| [70] | Risks | Supply chain | Electronic | Taiwan |

| [71] | Barrier | Supply chain | Manufacturing | Not specified |

| [72] | Risks | Green supply chain | Pharmaceutical | India |

| [73] | Risks | Green supply chain | Plastic engineering | India |

| [69] | Success factors | Reverse logistics | Manufacturing | India |

| [74] | Barrier | Supply chain | Auto manufacture | India |

| [20] | Risks | Supply chain | Pharmaceutical | Bangladesh |

| [36] | Barriers | Supply chain | Manufacturing | Bangladesh |

| [75] | Risks | Green supply chain | Textile industry | Pakistan |

| [76] | Barriers | Supply chain | Humanitarian | Iran |

| [77] | Risks | Supply chain | Not specified | Not specified |

| [78] | Risks | Supply chain | Manufacturing | US |

| [79] | Risks | Reverse logistics | Plastic recycling | India |

| [80] | Risks | Supply chain | Automotive | India |

| [81] | Factors | Supply chain | Not specified | India |

| [82] | Irregularities | Procurement | Public construction | India |

| [83] | Factors | Green supply chain | Construction | India |

| [84] | Risks | Inbound supply chain management | Not specified | Not specified |

| Importance Intensity | Definition | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Equal Importance | Two activities contribute equally to the objective |

| 3 | Moderate importance | Experience and judgement slightly favor one over another |

| 5 | Strong importance | Experience and judgement strongly favor one over another |

| 7 | Very strong importance | Activity is strongly favored, and its dominance is demonstrated in practice |

| 9 | Absolute importance | The importance of one over another, affirmed in the highest possible order |

| 2, 4, 6, 8 | Intermediate values | Used to represent the compromise between the priorities listed above |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khan, M.R.; Alam, M.J.; Tabassum, N.; Khan, N.A. A Systematic Review of the Delphi–AHP Method in Analyzing Challenges to Public-Sector Project Procurement and the Supply Chain: A Developing Country’s Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14215. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114215

Khan MR, Alam MJ, Tabassum N, Khan NA. A Systematic Review of the Delphi–AHP Method in Analyzing Challenges to Public-Sector Project Procurement and the Supply Chain: A Developing Country’s Perspective. Sustainability. 2022; 14(21):14215. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114215

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhan, Md. Raquibuzzaman, Mohammad Jahangir Alam, Nazia Tabassum, and Niaz Ahmed Khan. 2022. "A Systematic Review of the Delphi–AHP Method in Analyzing Challenges to Public-Sector Project Procurement and the Supply Chain: A Developing Country’s Perspective" Sustainability 14, no. 21: 14215. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114215

APA StyleKhan, M. R., Alam, M. J., Tabassum, N., & Khan, N. A. (2022). A Systematic Review of the Delphi–AHP Method in Analyzing Challenges to Public-Sector Project Procurement and the Supply Chain: A Developing Country’s Perspective. Sustainability, 14(21), 14215. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114215