Wildlife Knowledge and Attitudes toward Hunting: A Comparative Hunter–Non-Hunter Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

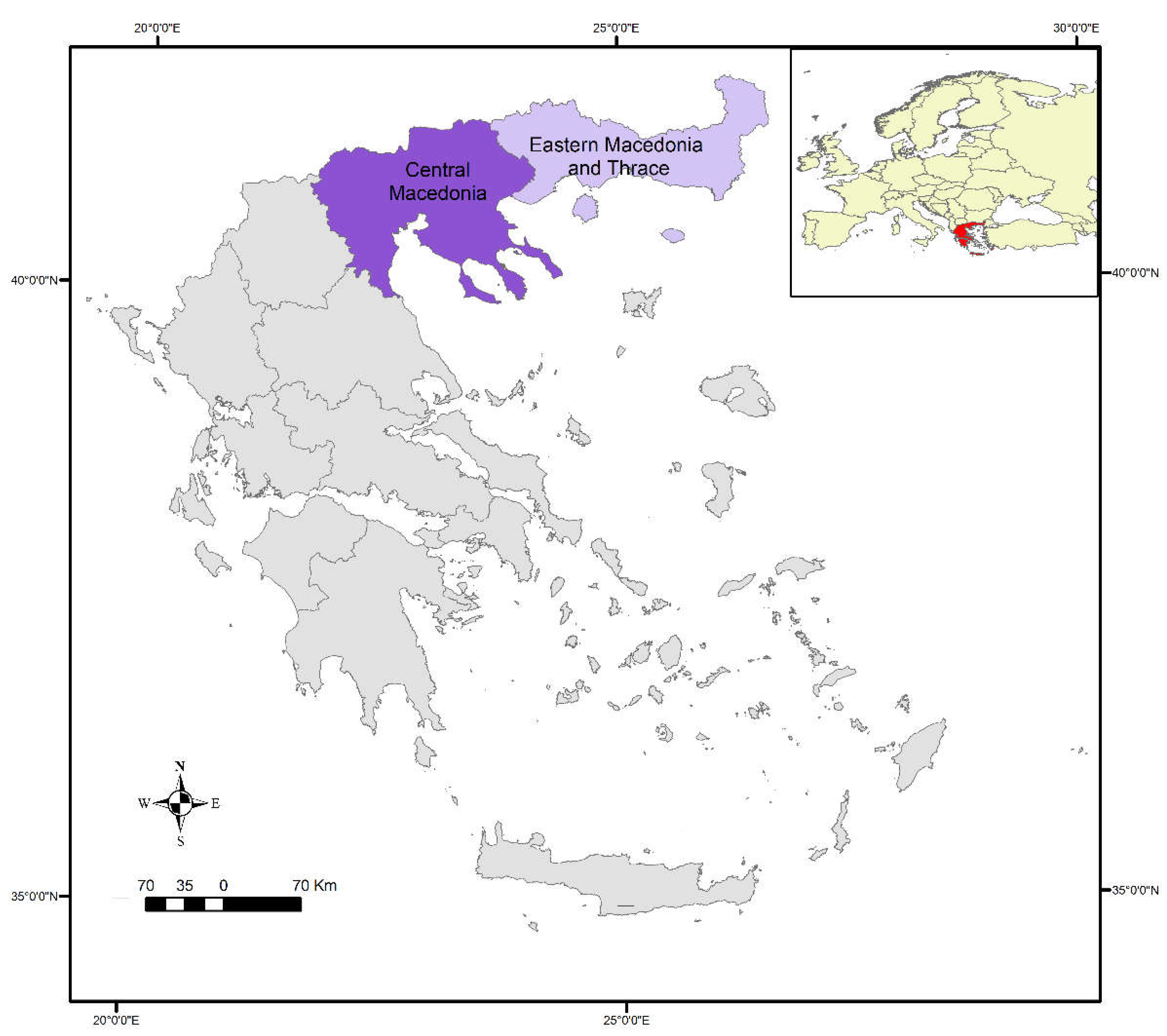

2.1. Sampling Protocol

2.2. Research Design

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographics

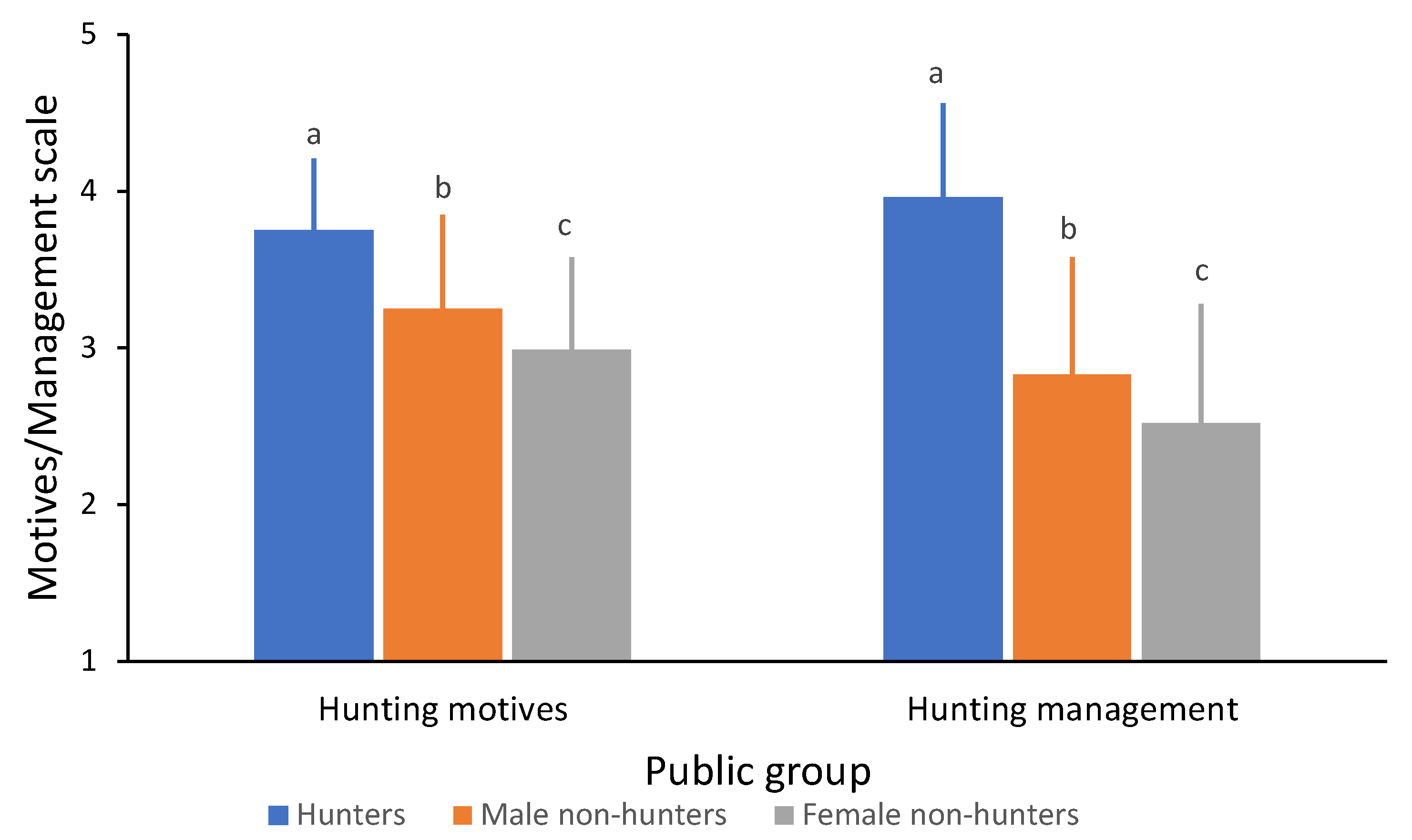

3.2. Acceptability of Motives for Hunting

3.3. Attitudes toward Hunting as a Management Tool

3.4. Knowledge about Wildlife

3.5. Effects of Sociodemographic Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Attitudes toward Hunting

4.2. Knowledge about Wildlife

4.3. The Effect of Sociodemographics

4.4. Management Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heberlein, T.A.; Ericsson, G. Ties to the countryside: Accounting for urbanites attitudes toward hunting, wolves, and wildlife. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2005, 10, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øian, H.; Skogen, K. Property and possession: Hunting tourism and the morality of landownership in rural Norway. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2016, 29, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, R. Outdoor Recreation; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wightman, A.; Higgins, P.; Jarvie, G.; Nicol, R. The cultural politics of hunting: Sporting estates and recreational land use in the highlands and Islands of Scotland. Cult. Sport Soc. 2002, 5, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.; Sandström, C.; Delibes-Mateos, M.; Arroyo, B.; Tadie, D.; Randall, D.; Hailu, F.; Lowassa, A.; Msuha, M.; Kereži, V.; et al. On the multifunctionality of hunting—An institution analysis of eight cases from Europe and Africa. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2013, 56, 531–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffelfinger, J.R.; Geist, V.; Wishart, W. The role of hunting in North American wildlife conservation. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2013, 70, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, L.H.; Jenkins, M.A.; Webster, C.R.W.; Zollner, P.A.; Shields, J.M. Herbaceous layer response to 17 years of controlled deer hunting in forested natural areas. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 175, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.L.; Decker, D.J.; Siemer, W.E.; Enck, J.W. Trends in hunting participation and implications for management of game species. In Trends in Outdoor Recreation, Leisure and Tourism; Gartner, W.C., Lime, D.W., Eds.; CAB International: Oxon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, J. Fishing and Hunting Recruitment and Retention in the US from 1990 to 2005. Addendum to the 2001 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and wildlife-Associated Recreation; Report 2001-11; US Fish & Wildlife Service: Arlington, VA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- FACE. Annual Report 2009–2010. Available online: http://www.face.eu/sites/deafult/files/attachments/data_hunters-region_sept_2010.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Pinet, J.-M. The Hunters in Europe. Federation of Associations for Hunting and Conservation of the EU. FACE. 1995. Available online: https://www.kora.ch/malme/05_library/5_1_publications/P_and_Q/Pinet_1995_The_hunters_in_Europe.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Cerri, J.; Ferretti, M.; Coli, L. Where the wild things are: Urbanization and income affect hunting participation in Tuscany, at the landscape scale. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2018, 64, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredo, M.J.; Sullivan, L.; Don Carlos, A.W.; Dietsch, A.M.; Teel, T.L.; Bright, A.D.; Bruskotter, J.T. America’s Wildlife Values: The Social Context of Wildlife Management in the US; Colorado State University, Department of Human Dimensions of Natural Resources: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Manfredo, M.J.; Teel, T.L.; Berl, R.E.W.; Bruskotter, J.T.; Kitayama, S. Social value shift in favour of biodiversity conservation in the United States. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, E.; Lee, J.G.; Widmar, N.J.O. Perceptions of hunting and hunters by US respondents. Animals 2017, 7, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daigle, J.J.; Hrubes, D.; Ajzen, I. A comparative study of beliefs, attitudes, and values among hunters, wildlife viewers, and other outdoor recreationists. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2002, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamborg, C.; Jensen, F.S.; Sandøe, P. Attitudes to the shooting of rear and release birds among landowners, hunters and the general public in Denmark. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontsiotis, V.J.; Vadikolios, G.; Liordos, V. Acceptability and consensus for the management of game and nongame crop raiders. Wildl. Res. 2020, 47, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liordos, V.; Kontsiotis, V.J.; Emmanouilidou, F. Understanding stakeholder preferences for managing red foxes in different situations. Ecol. Process. 2020, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R. Public perceptions of predators, particularly the wolf and coyote. Biol. Conserv. 1985, 31, 167–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J. Extinction of experience: The loss of human–nature interactions. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louv, R. The Nature Principle: Human Restoration and the end of Nature-deficit Disorder; Algonquin Books: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Echeverri, A.; Karp, D.S.; Naidoo, R.; Tobias, J.A.; Zhao, J.; Chan, K.M.A. Can avian functional traits predict cultural ecosystem services? People Nat. 2020, 2, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCleery, R.A.; Moorman, C.E.; Peterson, M.N. (Eds.) Urban Wildlife Conservation: Theory and Practice; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fazio, R.H.; Chen, J.; McDonel, E.C.; Sherman, S.J. Attitude accessibility, attitude behavior consistency, and the strength of the object-evaluation association. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 47, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holsman, R.H. Goodwill hunting? Exploring the role of hunters as ecosystem stewards. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2000, 28, 808–816. [Google Scholar]

- Loveridge, A.J.; Reynolds, J.C.; Milner-Gulland, E.J. Does sport hunting benefit conservation? In Key Topics in Conservation Biology; Macdonald, D.W., Service, K., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 224–241. [Google Scholar]

- Bouthillier, F.; Shearer, K. Understanding knowledge management and information management: The need for an empirical perspective. Inf. Res. 2002, 8, 141. Available online: http://InformationR.net/ir/8-1/paper141.html (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- García-López, R.; Villegas, A.; Pacheco-Coronel, N.; Gómez-Álvarez, G. Traditional use and perception of snakes by the Nahuas from Cuetzalan del Progreso, Puebla, Mexico. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017, 13, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liordos, V.; Kontsiotis, V.J.; Nevolianis, C.; Nikolopoulou, C.E. Stakeholder preferences and consensus associated with managing an endangered aquatic predator: The Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra). Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2019, 24, 446–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, A.; Yonle, R. Socio-ecological assessment of squamate reptiles in a human-modified ecosystem of Darjeeling, Eastern Himalaya. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2022, 27, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, M.D.; Jones, M.F.; Criscione, A. The Sportsman’s Voice: Hunting and Fishing in America; Venture Publishing: State College, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Teel, T.L.; Krannich, R.S.; Schmidt, R.H. Utah stakeholders’ attitudes toward selected cougar and black bear management practices. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2002, 30, 2–15. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3784630 (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Ljung, P.E.; Riley, S.J.; Heberlein, T.A.; Ericsson, G. Eat prey and love: Game-meat consumption and attitudes toward hunting. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2012, 36, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamborg, C.; Søndergaard Jensen, F. Attitudes toward recreational hunting: A quantitative survey of the general public in Denmark. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2017, 17, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedman, R.C.; Decker, D.J. Illuminating an overlooked hunting stakeholder group: Nonhunters and their interest in hunting. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 1996, 1, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEECC. Forest Service Activities for the Year 2010; Ministry of Environment, Energy and Climate Change Report: Athens, Greece, 2012. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Sokos, C.K. The Disappearance of Greek Hunters: Predicting Hunting Licences. Available online: https://www.ihunt.gr/%CE%B7-%CE%B5%CE%BE%CE%B1%CF%86%CE%AC%CE%BD%CE%B9%CF%83%CE%B7-%CF%84%CF%89%CE%BD-%CE%B5%CE%BB%CE%BB%CE%AE%CE%BD%CF%89%CE%BD-%CE%BA%CF%85%CE%BD%CE%B7%CE%B3%CF%8E%CE%BD-%CF%80%CF%81%CF%8C%CE%B2%CE%BB/ (accessed on 15 June 2022). (In Greek).

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision (ST/ESA/SER.A/420). United Nations. Available online: https://population.un.org/wup/Publications/Files/WUP2018-Report.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Liordos, V. Membership trends and attitudes of a Greek hunting community. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2014, 60, 821–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellenic Statistical Authority. Population Census 2011. Available online: http://www.statistics.gr/portal/page/portal/ESYE/PAGE-census2011 (accessed on 15 June 2022). (In Greek).

- Vaske, J.J. Survey Research and Analysis: Applications in Parks, Recreation and Human Dimensions; Venture Publishing Inc.: State College, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning EMEA: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Grandy, J.W.; Stallman, E.; Macdonald, D.W. The science and sociology of hunting: Shifting practices and perceptions in the United States and Great Britain. In The State of the Animals II; Salem, D.J., Rowan, A.N., Eds.; Humane Society Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 107–130. [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan, D.C.; Leitch, K. Conservation with a gun: Understanding landowner attitudes to deer hunting in the Scottish Highlands. Hum. Ecol. 2008, 36, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treves, A.; Martin, K.A. Hunters as stewards of wolves in Wisconsin and the northern Rocky Mountains, USA. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2011, 24, 984–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, G.; Heberlein, T.A. “Jägare talar naturens språk” (Hunters speak nature’s language): A comparison of outdoor activities and attitudes toward wildlife among Swedish hunters and the general public. Z. Jagdwiss. 2002, 48, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; Larson, L.; Dayer, A.; Stedman, R.; Decker, D. Are wildlife recreationists conservationists? Linking hunting, birdwatching, and pro-environmental behavior. J. Wildl. Manag. 2015, 79, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, A.; Delibes-Mateos, M.; Caro, J.; Viñuela, J.; Díaz-Fernández, S.; Casas, F.; Arroyo, B. Does small-game management benefit steppe-birds of conservation concern? A field study in central Spain. Anim. Conserv. 2015, 18, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Anaya, A.; Herrero, J.; García-Serrano, A.; García-González, R.; Prada, C. Wild boar battues reduce crop damages in a protected area. Folia Zool. 2016, 65, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez-López, A.; Alkemade, R.; Schipper, A.M.; Ingram, D.J.; Verweij, P.A.; Eikelboom, J.A.J.; Huijbregts, M.A.J. The impact of hunting on tropical mammal and bird populations. Science 2017, 356, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, B.; Monaco, A.; Bath, A.J. Beyond standard wildlife management: A pathway to encompass human dimension findings in wild boar management. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2015, 61, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liordos, V. Sociodemographic analysis of hunters’ preferences: A Greek hunting club perspective. Zool. Ecol. 2014, 24, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, T.B.; McKeegan, D.E.F.; Cribbin, C.; Sandøe, P. Animal ethics profiling of vegetarians, vegans and meat-Eaters. Anthrozoös 2016, 29, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmyhr, L.; Willebrand, T.; Hörnell-Willebrand, M. General experience rather than of local knowledge is important for grouse hunters bag size. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2012, 17, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.A.; Graefe, A.R. Effect of harvest success on hunter attitudes toward white-tailed deer management in Pennsylvania. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2001, 6, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, A.J. ‘Bats, snakes and spiders, oh my!’ How aesthetic and negativistic attitudes, and other concepts predict support for species protection. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liordos, V.; Kontsiotis, V.J.; Anastasiadou, M.; Karavasias, E. Effects of attitudes and demography on public support for endangered species conservation. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 595, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liordos, V.; Kontsiotis, V.J.; Kokoris, S.; Pimenidou, M. The two faces of Janus, or the dual mode of public attitudes towards snakes. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 621, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, J.N.; Gramann, J.H. Predicting effectiveness of wildlife education programs: A study of students’ attitudes and knowledge toward snakes. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 1989, 17, 501–509. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3782720 (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Ballouard, J.M.; Provost, G.; Barre, D.; Bonnet, X. Influence of a field trip on the attitude of schoolchildren toward unpopular organisms: An experience with snakes. J. Herpetol. 2012, 46, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, S.; Jacobson, S.K. Human-Wildlife Conflict and Environmental Education: Evaluating a Community Program to Protect the Andean Bear in Ecuador. J. Environ. Educ. 2012, 43, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greving, H.; Bruckermann, T.; Schumann, A.; Straka, T.M.; Lewanzik, D.; Voigt-Heucke, S.L.; Marggraf, L.; Lorenz, J.; Brandt, M.; Voigt, C.C.; et al. Improving attitudes and knowledge in a citizen science project about urban bat ecology. Ecol. Soc. 2022, 27, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Motive Statements a Hunting Is Acceptable Because... | Hunters (n = 146) | Non-Hunters (n = 315) | F2,458 | Factor Loadings b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 156) | Female (n = 159) | Hunters | Non-Hunters | |||

| It promotes contact with nature. | 4.88 ± 0.38 A | 3.77 ± 1.13 B | 3.45 ± 1.25 B | 84.803 *** | 0.91 | 0.72 |

| It is exciting. | 4.69 ± 0.67 A | 3.75 ± 0.96 B | 3.65 ± 0.93 B | 68.953 *** | 0.93 | 0.62 |

| It provides identity. | 3.13 ± 1.41 A | 3.31 ± 1.03 A | 3.29 ± 1.10 A | 2.314 | 0.69 | 0.65 |

| It is an important means of socializing. | 4.21 ± 1.09 A | 3.45 ± 1.13 B | 3.09 ± 1.14 B | 32.472 *** | 0.88 | 0.64 |

| It is a source of pride. | 3.42 ± 1.38 A | 4.35 ± 0.73 B | 4.06 ± 0.99 B | 49.556 *** | 0.80 | — |

| It offers peace and quiet and helps in reducing stress. | 4.81 ± 0.63 A | 3.92 ± 0.93 B | 3.66 ± 0.74 B | 89.677 *** | 0.93 | 0.66 |

| It is a recreational activity. | 4.77 ± 0.65 A | 2.38 ± 1.61 B | 2.09 ± 1.45 B | 182.185 *** | 0.75 | 0.83 |

| It is done for collecting trophies. | 1.83 ± 1.12 A | 1.52 ± 0.98 AB | 1.34 ± 0.78 B | 8.465 *** | 0.66 | 0.72 |

| It provides meat. | 2.00 ± 1.05 A | 2.78 ± 1.37 B | 2.26 ± 1.27 A | 19.140 *** | 0.69 | — |

| Attitude Statements a | Hunters (n = 146) | Non-Hunters (n = 315) | F2,458 | Factor Loadings c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 156) | Female (n = 159) | Hunters | Non-Hunters | |||

| It is acceptable to hunt animals when their populations are abundant. | 3.88 ± 1.11 A | 3.55 ± 1.14 A | 2.83 ± 1.23 B | 35.767 *** | 0.84 | 0.64 |

| It is acceptable to hunt animals that were reared and released by people. | 3.52 ± 1.50 A | 2.84 ± 1.01 B | 2.49 ± 1.09 B | 30.497 *** | 0.80 | 0.84 |

| Hunting helps keep nature in balance. | 4.21 ± 1.00 A | 3.23 ± 1.21 B | 2.86 ± 1.18 B | 55.662 *** | 0.92 | 0.65 |

| Hunting helps reduce agricultural damage by reducing animal populations. | 4.08 ± 1.17 A | 3.00 ± 1.41 B | 2.63 ± 1.27 B | 60.763 *** | 0.84 | 0.72 |

| Hunting helps control predators such as foxes and martens. | 4.13 ± 1.07 A | 2.47 ± 1.49 B | 2.51 ± 1.51 B | 82.335 *** | 0.82 | 0.79 |

| Hunting commonly results in a species becoming threatened or endangered. b | 3.77 ± 1.20 A | 1.75 ± 0.91 B | 1.80 ± 1.13 B | 146.762 *** | 0.62 | 0.65 |

| Hunting helps control wildlife diseases by reducing animal populations. | 4.02 ± 1.18 A | 3.11 ± 0.79 B | 2.89 ± 0.66 B | 60.078 *** | 0.78 | — |

| Hunting provides funds used to manage other wildlife species that are not hunted. | 3.94 ± 1.29 A | 2.63 ± 1.44 B | 2.26 ± 1.33 B | 65.546 *** | 0.85 | 0.83 |

| The demand for hunting maintains wildlife habitats. | 4.10 ± 0.93 A | 2.92 ± 1.02 B | 2.39 ± 1.00 C | 116.385 *** | 0.86 | — |

| Knowledge Statements a | Hunters (n = 146) | Non-Hunters (n = 315) | F2,458 | Factor Loadings c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 156) | Female (n = 159) | Hunters | Non-Hunters | |||

| Brown bears mostly eat meat. b | 3.63 ± 1.30 A | 3.54 ± 1.37 A | 3.92 ± 1.25 A | 1.077 | — | — |

| Black storks nest in trees. | 3.71 ± 0.65 A | 2.75 ± 0.85 B | 2.95 ± 1.08 B | 31.766 *** | 0.84 | — |

| Common European adders are male nose-horned vipers. b | 3.52 ± 1.02 A | 2.93 ± 0.93 B | 2.85 ± 0.85 B | 22.375 *** | 0.58 | 0.54 |

| Eurasian otters are rodents. b | 2.50 ± 1.21 A | 2.27 ± 1.25 A | 2.43 ± 1.36 A | 1.002 | 0.61 | 0.59 |

| Eurasian otters mostly eat cultivated seeds and fruits. b | 4.35 ± 0.99 A | 3.03 ± 1.19 B | 2.66 ± 1.09 B | 103.861 *** | — | 0.52 |

| Northern, white-breasted hedgehogs mostly eat leaves and grasses. b | 3.25 ± 1.48 A | 2.16 ± 0.95 B | 2.28 ± 1.00 B | 39.597 *** | — | 0.50 |

| Red foxes might carry rabies | 4.54 ± 0.94 A | 4.36 ± 0.74 A | 4.32 ± 0.81 A | 1.381 | 0.73 | — |

| Red and roe deer shed their antlers each year. | 4.38 ± 0.97 A | 3.23 ± 1.12 B | 3.09 ± 1.43 B | 49.912 *** | 0.65 | 0.63 |

| Roe deer are monogamous. | 2.52 ± 1.16 A | 2.73 ± 1.18 A | 2.92 ± 1.15 A | 1.945 | — | 0.53 |

| Turtles are a common sight in winter. b | 3.90 ± 1.40 A | 2.24 ± 1.09 B | 2.23 ± 0.96 B | 89.655 *** | 0.77 | 0.67 |

| Brown hares nest in burrows. b | 3.77 ± 1.64 A | 2.33 ± 1.29 B | 2.51 ± 1.45 B | 43.714 *** | — | 0.53 |

| Female brown hares give birth to one young each year. b | 4.56 ± 1.02 A | 3.88 ± 1.26 B | 3.80 ± 1.38 B | 22.587 *** | — | 0.56 |

| Ducks feed during the day and sleep during the night. b | 4.12 ± 1.23 A | 2.34 ± 1.20 B | 2.54 ± 1.25 B | 98.231 *** | 0.67 | 0.59 |

| Female ducks have colorful plumage. b | 4.48 ± 1.00 A | 3.40 ± 1.27 B | 3.65 ± 1.32 B | 35.901 *** | 0.57 | — |

| Eurasian woodcocks prefer wet, densely vegetated habitats. | 4.79 ± 0.54 A | 3.72 ± 1.03 B | 3.75 ± 0.97 B | 76.066 *** | 0.68 | — |

| Rock partridges are galliforms. | 4.40 ± 0.87 A | 3.65 ± 0.88 B | 3.58 ± 0.97 B | 37.197 *** | 0.81 | — |

| Rock partridges form pairs at the end of winter. | 4.10 ± 0.85 A | 2.91 ± 0.64 B | 2.89 ± 0.72 B | 134.868 ** | — | 0.59 |

| Turtle doves are migratory birds. | 4.71 ± 0.89 A | 3.43 ± 1.15 B | 3.68 ± 1.11 | 73.934 *** | — | — |

| Wild boars can mate with domestic pigs. | 4.56 ± 0.83 A | 3.35 ± 1.12 B | 3.26 ± 0.96 B | 78.025 *** | 0.77 | 0.65 |

| Wild boars take mud baths to cool themselves. b | 2.85 ± 1.67 A | 1.90 ± 0.91 B | 2.08 ± 1.04 B | 22.342 *** | 0.83 | — |

| Hunters (n = 146) | Non-Hunters (n = 315) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hunting and Management | Hunting Motives | Wildlife Knowledge | Hunting and Management | Hunting Motives | Wildlife Knowledge | |

| Hunting motives | 0.388 *** | - | - | 0.489 *** | - | - |

| Wildlife knowledge | 0.208 *** | 0.056 | - | 0.208 *** | 0.134 * | - |

| Age | −0.078 | −0.028 | −0.016 | 0.244 *** | 0.558 *** | 0.521 *** |

| Gender (female) | - | - | - | −0.123 * | −0.147 * | 0.076 |

| Education (higher) | 0.061 | 0.007 | 0.057 | −0.05 | 0.033 | 0.234 *** |

| Pet ownership | 0.373 *** | 0.023 | 0.074 | 0.001 | −0.009 | 0.031 |

| Eat game | - | - | - | 0.118 * | 0.074 | −0.027 |

| Hunters’ kin/friends | 0.078 | 0.205 *** | 0.075 | 0.109 * | 0.151 * | 0.172 ** |

| Hunting experience | 0.279 *** | 0.054 | 0.329 *** | - | - | - |

| Constant | 1.569 | 3.933 *** | 4.184 *** | 0.873 ** | 1.351 *** | 1.991 *** |

| adj. R2 | 0.337 | 0.194 | 0.219 | 0.715 | 0.527 | 0.290 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Raftogianni, G.; Kontsiotis, V.J.; Liordos, V. Wildlife Knowledge and Attitudes toward Hunting: A Comparative Hunter–Non-Hunter Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14541. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114541

Raftogianni G, Kontsiotis VJ, Liordos V. Wildlife Knowledge and Attitudes toward Hunting: A Comparative Hunter–Non-Hunter Analysis. Sustainability. 2022; 14(21):14541. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114541

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaftogianni, Georgia, Vasileios J. Kontsiotis, and Vasilios Liordos. 2022. "Wildlife Knowledge and Attitudes toward Hunting: A Comparative Hunter–Non-Hunter Analysis" Sustainability 14, no. 21: 14541. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114541

APA StyleRaftogianni, G., Kontsiotis, V. J., & Liordos, V. (2022). Wildlife Knowledge and Attitudes toward Hunting: A Comparative Hunter–Non-Hunter Analysis. Sustainability, 14(21), 14541. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114541