1. Introduction

Promoting economic growth and improving people’s livelihood by new urbanization is an important strategy for long-term development of Chinese society [

1]. For a long time, China’s local governments had no financing rights and generally relied on financing platforms to make up for the financial gap of new urbanization. The financing platform model has played an active role in the new urbanization, but it has also produced problems such as the government’s dependence on land finance and the neglect of debt risk [

2,

3,

4]. After 2013, social capital was used to participate in urban infrastructure investment and operation through franchise and other ways, broadening the financing channels and operation mode of new urbanization, and thus the government began to actively try to improve the public-private partnership (PPP) (Domestic and foreign enterprise legal persons have established modern enterprise management systems, which do not include financing platform companies and other state-owned enterprises controlled by the government at the corresponding level.) [

5]. How do we understand the transformation of the development model of new urbanization from a local financing platform to a PPP model? Exploring the internal logic of the transformation of the development model of new urbanization from a local financing platform to a PPP model is helpful to clarify the relationship between local government and local financing platforms. This helps to design the top-level architecture of local financing platform transformation, which is helpful to induce social capital to carry out continuous innovation, and constantly strengthen the project standard innovation management, and truly form a long-term partnership. This also helps the PPP model to achieve the best results in the construction of new urbanization, and to avoid the alienation of the local financing platform and ensure the smooth landing of PPP projects which helps to resolve local government debt risk and reduce the pressure on local debt. Lastly, this helps to give full play to the synergy between government and market resources to promote sustained and healthy economic development.

There have been many studies on the cooperation between the public and private sectors. Based on the incomplete contract theory, Ref. [

6] discussed the optimal boundary problem of the public sector in an incomplete contract framework and proposed a theoretical model (HSV model) for public sector ownership and private sector contracting. From the perspective of incomplete contract and property rights theory, this model analyzes the different effects of public sector ownership and private sector contracting on product and service cost and quality improvement input. As to the question of the optimal scope for the provision of public goods and services by the public sector, the authors considered that privatization measures should be taken in cases where the adverse effects on quality reduction in the cost of goods and services could be controlled, or where the problem of public sector employees sheltering interest groups is serious; conversely, public goods and services should be provided by the public sector. The HSV model considers the impact of different types of partners on the allocation of control rights but does not consider the impact of product attributes on the allocation of control rights. Ref. [

7] studied the allocation of control rights between the public and private sectors in the co-production of pure public goods with incomplete contract theory. Ref. [

8] studied the allocation of control rights between the public and private sectors when the product is quasi-public goods with incomplete contract theory. On the basis of incomplete contract theory, Ref. [

9] also established an analytical framework for the optimal allocation of different tasks (such as design, construction, operation, etc.) in PPP projects, examined the benefits and costs of integration from the perspective of property rights and incentives, and explored the efficiency of public-private partnerships based on the impact of ownership on innovative investment incentives. It is proven that when the government’s requirements for the early design stage are easier to be written into the PPP contract and the requirements for the later construction stage are not easy to be written into the PPP contract, the ‘bundling’ method should be adopted. That is, the same enterprises bear the PPP project design and construction at the same time; on the contrary, the design and construction tasks of PPP projects should be handed over to different enterprises by unbundling. The above theory explains the economic logic of the PPP model in the framework of incomplete contracts, and also provides the most basic theoretical basis for studying the distribution of control rights when the public sector and the private sector adopt the PPP model to cooperate in the production of public goods. However, it based on the public sector and the private sector. There is still a big difference between the private sector and the social capital in China’s PPP. At the same time, it does not take into account the role of the Chinese government in the development of the PPP model and cannot well understand the development of PPP in China and the development model of promoting the economy.

The development of PPP model in China has embedded its own unique style. In the process of new urbanization, due to rapid urbanization and fiscal decentralization, local governments choose to set up financing platform companies to alleviate the shortage of funds for local government construction through ‘local financing’, and also accumulate large debt risks [

10,

11]. The PPP model can not only broaden the source of funds, but also improve the efficiency of project construction, strengthen the government supervision function, alleviate the level of local debt, and help to improve the quality and efficiency of new urbanization construction [

12]. In the process of promoting PPP projects in China, the inconsistency between the goals of local governments and the central government leads to games, such as the game of fiscal and tax payment and the game of financial supervision [

13,

14,

15] and local governments that compete for growth [

16,

17,

18,

19], which plays a vital role. We will explore the following two issues: 1. whether local government debt promotes economic growth in the neoclassical framework and 2. whether PPP can be used as an alternative to local financing platforms to boost private investment and economic development. This can well explain the behavior of local governments in local debt expansion and help to understand the intrinsic motivation of the Chinese government to promote PPP development.

The relationship between public debt and economic growth is a time-honored issue. The literature [

20,

21,

22,

23] used the theoretical approach of neoclassical growth models to demonstrate that an increase in public debt reduces economic growth rates. Some of the empirical literature also confirms the negative relationship between government debt and economic growth [

24,

25,

26]. Ref. [

27] reviewed the existing 40 economic literature studies published during the period 2010 to 2020 on the relationship between public debt levels and economic growth and found that there is a nonlinear debt threshold above which debt has a significant deleterious impact on growth rates. At present, there are relatively few studies on local government debt and regional economic growth. China’s local government debt in recent years due to social concern and heated debate has gradually become a topic of academic attention. The existing literature shows that local government debt has a promoting effect on public goods financing and regional economic growth [

28,

29,

30,

31]. Based on the local debt balance data of 30 provinces in China from 2010 to the end of 2014, Ref. [

32] conducted an empirical study on the economic growth effect of local debt. It is found that there is an obvious threshold effect of economic growth in China’s local debt: when the debt rate is higher than about 112%, the positive significant effect basically approaches 0.

Local government debt to promote economic growth may ignore the cost of government intervention or government failure, especially ignoring the importance of investment cost compensation, so that the actual economic growth is based on unreality (such as relying on debt), eventually leading to economic and social unsustainable. Therefore, this paper understands the PPP model as an alternative to the urban investment bond and local financing platform model. Many literature studies [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37] put forward the PPP model instead of the financing platform to prevent local government debt risk, but few empirical literature studies examined the substitution relationship between the PPP model and the financing platform. In order to make up for the lack of relevant research, this paper integrates the relevant data of 287 prefecture-level cities in the CBRC’s (China Banking Regulatory Commission) list of local government financing platforms, the PPP of the Treasury Department’s project library [

38], the urban investment debt of Wind information [

39], CEIC (China entrepreneur Investment Club) [

40], and the China Urban Statistical Yearbook [

41]. Under the neoclassical growth framework, this paper empirically studies the operation mechanism of the financing platform and predicts the demand for PPP projects in prefecture-level cities. The study found that the financing platform model formed the local government’s dependence on land finance, and under its intervention, pushed up housing prices but not conducive to economic growth. Moreover, the existence of the financing platform hinders the development of PPP projects and is not conducive to the transformation and development of investment and financing.

The contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

The research on the relationship between public debt and economic growth basically focuses on the national level, which is also different from the provincial data of [

32]. Our research is based on prefecture-level city data, which has richer information and avoids provincial-level data. Ignoring the differences in industrialization, marketization, and urbanization between cities within provinces and regions may bring about cognitive biases, enriching the Chinese case study on the relationship between debt and economic growth.

Urban investment bonds and local financing platform data were constructed to study the operating mechanism of the local government financing platform and deepen the understanding of local governments on land financial dependence.

It verifies the alternative relationship between the PPP model and local financing platform model, deepens the understanding of PPP promoting economic growth mechanism, and makes up for the lack of relevant literature.

It enriches the economic growth theory of new institutional economics and provides a ‘Chinese model’ for developing countries.

The second part of this paper focuses on the research background and the inner logic of model selection from the perspective of literature. The third part is a statistical descriptive analysis of the data and an elaboration of the empirical research methodology. The fourth part is the prediction of the demand for PPP projects, and finally the conclusion and policy enlightenment of this paper.

2. Research Background and Internal Logic of Model Selection

Moderate government debt promotes economic growth, and excessive debt is not conducive to sustainable economic development. In terms of economic theory, at a moderate level of government debt, government debt may induce growth. Because government debt is used for public investment, the improvement of production efficiency through better services and infrastructure will drive the investment and production behavior of the private sector, which will have an impact on output and the real economy. Ref. [

42], using cross-sectional data from a group of countries, also concluded that public investment has a positive effect on private investment and economic growth. Ref. [

43] analyzed the data samples of Latin American countries from 1980 to 1995, and the results show that public investment has a significant pulling effect on private investment. Ref. [

44] selected the data of 19 representative developing countries from 1970 to 1998 for research. The results show that public investment has a significant effect on private investment and economic growth in major developing countries. At high debt levels, however, expected future tax increases would reduce the likely positive impact of government debt. The expansion of government debt has brought rising capital costs and future tax increases, and people will reduce investment and consumption, which could crowd out private investment and lead to lower output. Ref. [

45]’s study showed that when there is excess supply in the labor market and excess demand in the commodity market, an increase in public investment will completely crowd out private investment. Using the data of the United States and Canada from 1949 to 1976, Ref. [

46] also showed that public investment has a certain crowding-out effect on private investment. Ref. [

47] studied the cross-sectional data of OECD countries and found that public investment has a negative effect on private investment and is not conducive to economic growth.

In the process of China’s economic growth, investment plays an important role. In 2009, China achieved a GDP growth rate of up to 8.7%, but capital formation alone contributed up to 8% to growth and 92.3% to GDP. It can be said that China’s economic growth is heavily dependent on investment. In the process of promoting new urbanization, the financing platform realizes external borrowing through land mortgage, which is an important way to obtain the funds needed for municipal project construction. In 1994, the tax-sharing reform was implemented. The tax-sharing financial management system was designed according to the principle of “combining the power of affairs (the power of governments at all levels to deal with social public affairs and economic affairs based on different functions) with the financial power (the power of governments at all levels to organize various fiscal revenues and arrange various fiscal expenditures),” which further standardized the financial relationship between the central and local governments. In order to obtain municipal project construction funds and promote local economic and social development, local governments gave birth to the financing platform [

48]. The implementation of the tax-sharing system reform has brought about vertical competition between financial power and administrative power, and horizontal competition among local governments with GDP growth rate as the performance evaluation mechanism of local officials [

49], making local governments establish local financing platforms and rely on land for financing [

50,

51,

52], promoting the rapid development of the urban economy.

In the development mode of local financing platforms, land acts as a leverage to leverage urban construction financing, which also leads to the risk of local excessive borrowing. Ref. [

53] found that for infrastructure investment, only 10% came from financial investment, 90% was related to land, land transfer funds accounted for about 30%, and 60% was obtained through land mortgage financing channels. On the one hand, land transfer fees increase year by year. On the other hand, land mortgage loan increases year by year. With the deepening of China’s economic development, the land finance model gradually shows many problems. The pattern of “seeking development by land” began to have a negative impact on economic development and urbanization [

54]; it also exposes local governments to financial and credit risks [

55]. Related land finance and debt data is shown in

Table 1.

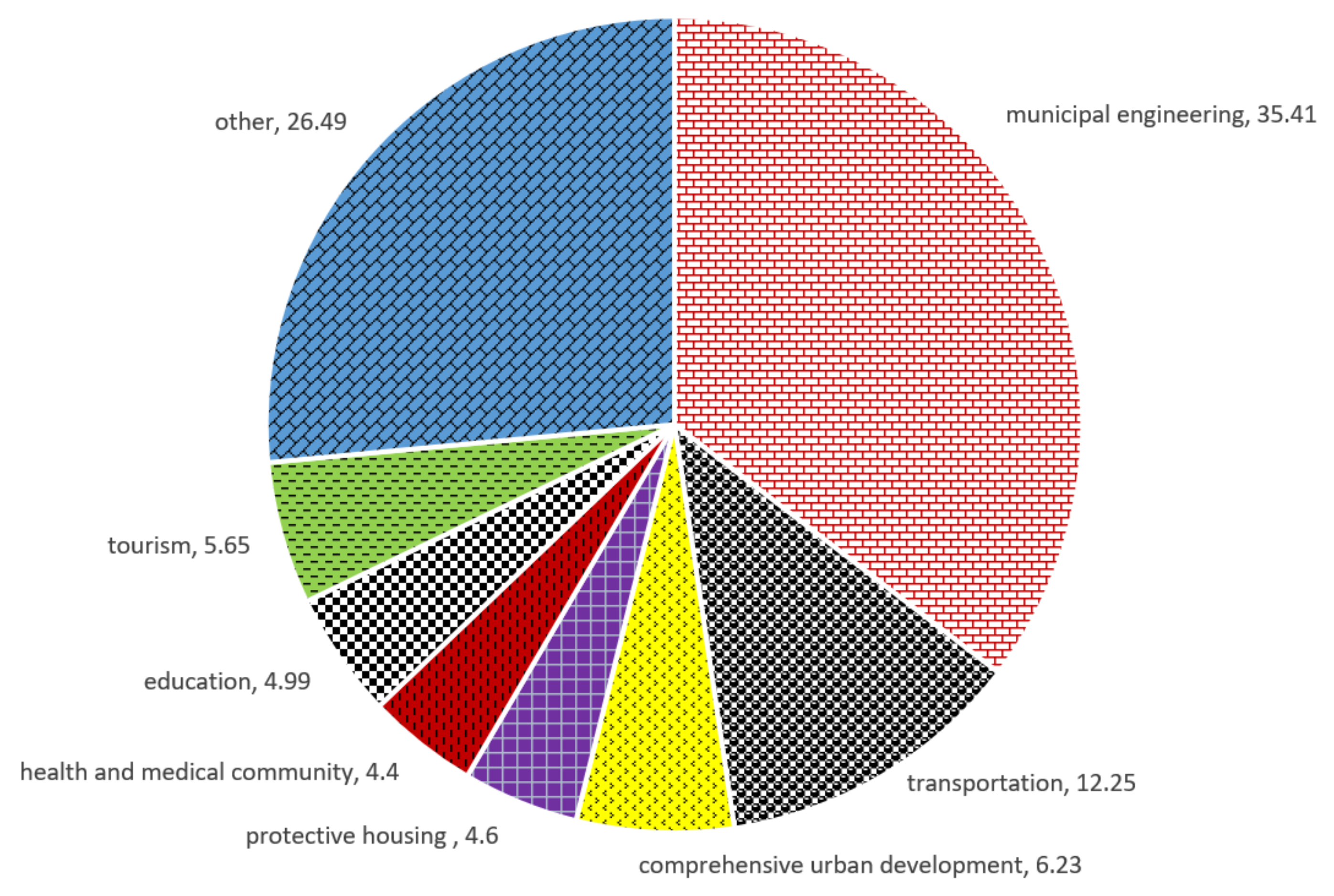

After the local financing platform is restricted, PPP projects can be used as a way to alleviate the financial pressure of local governments. According to data published by the National Audit Office (2013), about 70 percent of local government debt expenditures in recent years have been directed to municipal and transport facilities, and about 10 percent to land reserves, with three expenditures accounting for about 80 percent of all expenditures. The above expenditure items are key business areas in which PPP models are currently involved (see

Figure 1), Municipal engineering accounted for 35.41%, transportation accounted for 12.25%, and urban comprehensive development accounted for 6.23%. Protective housing accounted for 4.6%. By attracting private capital into municipal projects, PPP mode changes the financing mode of financing platforms, reduces the dependence of local governments on land finance, and reduces the debt risk of financing platforms. At the same time, local governments can allocate more financial resources to the field of social development.

In the investment and operation of urban infrastructure, PPP model, as a new management model, is easy to promote the establishment and improvement of incentive mechanism and improve the efficiency of construction and operation. The nonstandard management of financing platform has gathered debt risks, prompting the government to achieve institutional innovation through the PPP model. As a new management mode, PPP mode helps to form incentive mechanism, realize the transformation of public sector from traditional plan to market, and the private sector from market to social service. This ‘double shift’ allows institutional innovation that leverages private investment while limiting local governments’ overreliance on financing platforms through land finance to complete the short-term task of urbanization, ignoring the long-term risk of local debt accumulation, thereby improving infrastructure construction and operational efficiency. Therefore, on 18 May 2014 and 7 July 2015, the National Development and Reform Commission issued “notices on the issuance of the first batch of infrastructure and other fields to encourage social investment projects” and “Measures for the management of infrastructure and public utilities franchises” to encourage and guide social capital to participate in the construction and operation of infrastructure and public utilities, thereby improving the quality and efficiency of public services. Ref. [

56] thinks that there are three differences between the PPP model and the traditional financing model: Firstly, financing is only one of the purposes of the PPP model, as the government and the public sector can also effectively use the production and management technology of the private sector through the PPP model. Secondly, the PPP model more considers the overall risk minimization, compared to the public and private pursuit of risk minimization, and can better resolve the risk. Thirdly, corresponding to risk control, the PPP model pursues the maximization of social comprehensive benefits. It can be seen that the PPP model is an effective integration of public interests and market interests at the operational mechanism level, forming a management and operational mechanism superior to the separate role of the government and the market.