1. Introduction to Urban Greenery in the Context of Climate Change

The issue of urban green spaces in the urban environment heavily resonated in discussions working around urban planning. All over the world, the urban environment issue, as well as its sustainability, the optimisation of its effect on the environment, and adaptation to climate change, have been addressed in the last few decades [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The importance of green spaces in the urban environment is gaining attention as a powerful tool in climatic adaptation strategies. Cities are homes to ever-increasing numbers of inhabitants, which hikes up the demand for space and unbuilt plots. Therefore, urban greenery is becoming a greatly desired article on the market, enhancing the quality of city life [

5,

6].

There is a lot of discussion on climate change today. Although the public receives ambiguous information from time-to-time, the latest reports on climate change prepared by more than 600 scientists from around the world are unambiguous in their conclusions [

7,

8]. A major part of the global increase in average temperature in the second half of the 20th century is conditioned by increasing anthropogenic greenhouse gas concentrations [

9,

10,

11].

Following the World Economic Forum Global Risks reports, climate change has been identified among the top five most serious global problems [

12]. It has been an ongoing issue of argument with no doubts regarding the warming progress—individual scenarios differ only in the values of the temperature increase (1.5–4.5 °C by 2100 on average) [

10]. Temperature increase brings wide ranging problems whereby the effects can be seen on a blanket basis in all sectors and spheres of human interest [

13,

14,

15]. Therefore, human society should prepare for the consequences of climate change and its future problems by adopting adaptation measures. Since most people around the world live in cities, densely urbanised areas are specific to climate change consequences [

16]. Considering known facts, the issue of sustainable development and climate change features appears more and more frequently in strategic documents and urban planning strategies [

17,

18].

Taking into account the Framework Convention on Climate Change (9 May 1992) and the Kyoto Protocol (16 February 2005), countries have adopted the aim of decreasing greenhouse gas emissions. Within this frame of reference, the European Commission issued several important papers, for example, the Green Paper, the White Paper, and the Europe 2020 Strategy [

19,

20].

Apart from legislation, the topicality of the issue is endorsed by the large number of events addressing climate change. “C 40 Cities” is an association of cities targeting to support measures that should result in a reduction in greenhouse gasses, having more than 80 of the world’s cities with more than 600 million inhabitants. The association focuses on consequences and improvements in public health and the life quality of citizens [

21].

Generally, urban green spaces are fundamental tools for improving microclimate conditions. It decreases temperature and makes the urban environment cooler, it also facilitates water management by absorbing rainwater [

22,

23]. Moreover, building greenery systems (on facades or roofs) improves the thermal performance of building construction. It helps to decrease dustiness and has irreplaceable social functions [

24,

25]. Therefore, green spaces in the urban environment should begin featuring in strategies and concepts for adapting to the consequences of climate change. In this context, the term “Smart City” was brought to the public’s attention; the concept articulates innovative solutions based on new technologies and supports communication [

26,

27]. As an intelligent city, Smart City “primarily consists of communication between the city and its inhabitants, with the aim of involving them in administration and changing their habits” [

28]. Many events are held in order to present and apply the latest Smart City solutions. To name the prominent ones, the recently hosted conferences and summits include, for example:

Summit Smart City 360—organised by the European Alliance for Innovation with the intention of connecting the private and public sectors with new technologies (also in Bratislava from 22–24 November 2016). It is a platform for exchanging new knowledge and experiences gained in the Smart City sphere and brings insights into the multi-disciplinary context of solving economic, social, and technological issues. It focuses on alternative energy issues, the Smart City, or transportation and combines research, industry, and government organisations.

SUSTAINIA—takes patronage over the community of inhabitants, organisations, and companies that work together to bringing new solutions to the sustainable development of cities. Every year, it issues publications that present readers with specific examples of innovative solutions: Cities 100, Sustainia 100 [

29].

Furthermore, urban green spaces are one of the main factors establishing the quality of urban environments; they fulfil not only micro-climate and health functions, but also aesthetic and psychological functions that directly influence the human population [

30]. When dealing with the influence of urban green spaces on humans, the human factor needs to be kept in mind [

30]. When viewed from a human perspective, these spaces are often perceived somewhat differently than they are when viewed from the perspective of urban planning. A living city is created by the variability of impulses and inspirations. Inhabitants who pass through the city perceive urban greenery through their current views and feelings.

1.1. Urban Greenery Issue Abroad and Contemporary Challenges

Initially, we analysed current urban greenery issues together with the different approaches taken by cities, emphasising new trends and the use of new technologies in participatory urban planning. It is generally known that green areas directly or indirectly fulfil several environmental functions. Due to these reasons, it is necessary to monitor the following factors in cities:

share of green areas per territory of built-up structures;

availability of green areas for inhabitants;

amount and/or size of green areas per inhabitant;

and connectivity of green areas in the structure of a municipality and in relation to the countryside.

The availability of green areas and public spaces for inhabitants reaches the value of 100% in some European cities, such as, for instance, Brussels, Copenhagen, Paris, Milan, and Madrid [

31]. European cities establish policies and specific solutions for the urban greenery issue in different ways. Even if adaptation mechanisms to climate change are in every urban plan and strategy, a variety of approaches apply [

32]. Approaches to the management and planning of urban greenery or towards the implementation of adaptation measures differ regarding the tools used and the level of comprehensiveness. Cities try to meet the set goals through formal regulations, public education, raise awareness initiatives, public participation, or using new beneficial technologies (

Table 1).

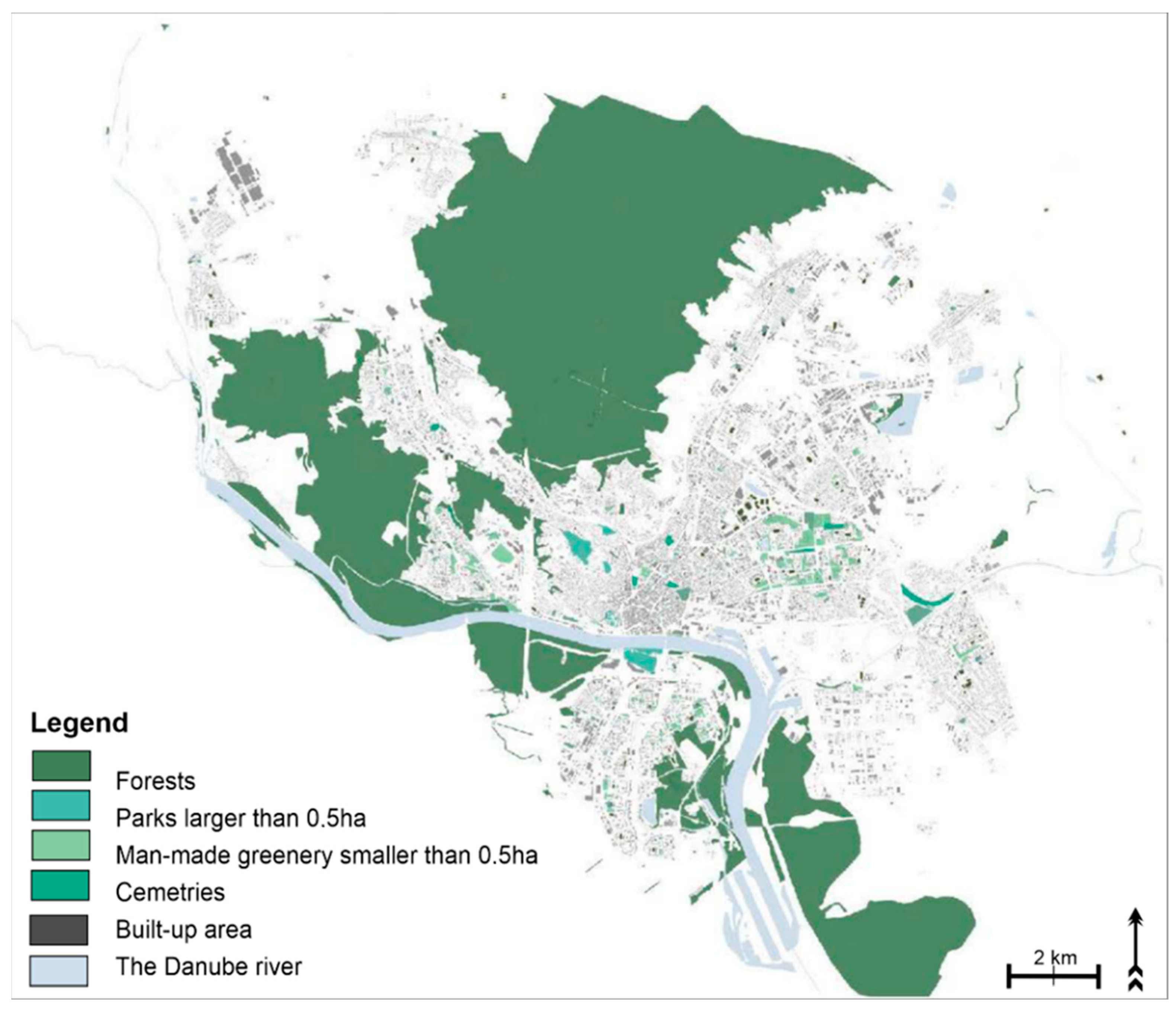

1.2. The Study Area of Bratislava and Its Climate Change Strategies

Bratislava is the capital and largest city of Slovakia. Officially, the population of the city is about 429,564. However, it is estimated to be more than 660,000—approximately 150% more inhabitants than state official figures [

37]. The estimated number of inhabitants is higher due to the temporary stays of people who work in the city but whose permanent residence is outside of the capital. Bratislava is located in southwestern Slovakia, and it has a specific geographical location. It spreads on the foothills of the Little Carpathians and concurrently occupying both banks of the Danube River and the left bank of the Morava River. Bordering Austria and Hungary, it is the only European capital that borders two sovereign states. It is only 18 kilometres from the border with Hungary and only 60 kilometres from the Austrian capital, Vienna. The city has a total area of 36,758 km

2, making it the second-largest city in Slovakia by area size [

38] (

Figure 1).

Bratislava lies in the north temperate zone and has a moderately continental climate with mean annual temperature (1990–2009) of around 10.5 °C (50.9 °F), average temperature of 21 °C (70 °F) in the warmest month and −1 °C (30 °F) in the coldest month, four distinct seasons, and precipitation spread rather evenly throughout the year. It is often windy, with a marked variation between hot summers and cold, humid winters. The city is in one of the warmest and driest parts of Slovakia [

39].

Recently, the transitions from winter to summer and summer to winter have been rapid, with short autumn and spring periods. Snow occurs less frequently than previously. Extreme temperatures (1981–2013)—record high: 39.4 °C (102.9 °F), record low: −24.6 °C (−12.3 °F). Some areas are vulnerable to floods from the Danube and Morava rivers. New flood protection has been built on both banks [

40].

Regarding the urban greenery issue, the Bratislava Municipal Authority published “Strategy on the Adverse Impacts of Climate Change in the Region of the Slovak Capital City of Bratislava” (hereinafter referred to only as “Strategy”) introducing appropriate adaptation and mitigation measures against climate change. In relation to urban greenery, the following measures have been proposed:

To increase the number of urban green spaces in the city by planting trees in streets and parking lots, creating small green areas (“pocket park”), greenery systems on building facades, and setting up greenery on roofs;

To improve the quality of urban green spaces;

To improve the accessibility of urban green spaces;

To ensure the revitalisation of selected green areas and renewed areas in courtyards [

41].

The idea to combine individual green areas into one integral green system and connect built-up areas with the countryside has been widely discussed over the last decade. The city tries to accomplish the green and blue infrastructure goals through incentives, instructions, and guidelines. The programme “Bratislava prepares for climate change” (2014–2016) presents the first example in this field. a. In the period from 19 August 2014 to 30 April 2016, it was a pilot area to demonstrate rainwater retention in an urbanised environment. The project was financed partly by the EEA and Norway Grants and from the national budget, with the total sum amounting to EUR 3,337,640. The pilot project’s aim was to give a practical exhibition of the state of preparedness against the consequences of climate change—increasing temperatures, heatwaves, and droughts alternating with downpours, primarily emphasising the issue of rainwater management, i.e., strengthening the spatial differentiation of urban greenery and consequently absorption areas. More than 20 projects were implemented as a part of the greenery programme in the city [

42].

The issue of planning public greenery on a city level falls within the competence of the Municipal Architect Office. Several programmes were set up to address the possibility of inhabitants participating in the resolution to the urban greenery issues. One of these programmes, “To adopt greenery”, allows inhabitants to take care of a green area of their choice [

42]. Furthermore, the Municipal Authority opened a small grant scheme programme to the city’s inhabitants with the intention of supporting the construction of rainwater retention elements on corresponding plots. The Municipal Authority has undertaken to contribute 50% of the funding on projects that cost up to EUR 1.000. With regard to newly projected rainwater retention facilities, inhabitants were provided with relevant consultancy services. The city uses a public website, “

www.bratislava.sk” (accessed on 27 October 2022), to communicate the demands, visions, and wishes of its inhabitants. It is an integrated website covering all areas of interest.

The city was basically historically formed by its ancient centre with the surrounding villages. There are 17 municipal districts (Staré Mesto, Ružinov, Vrakuňa, Podunajské Biskupice, Nové Mesto, Rača, Vajnory, Karlova Ves, Dúbravka, Lamač, Devín, Devínska Nová Ves, Záhorská Bystrica, Petržalka, Jarovce, Rusovce, Čuňovo). The districts also administer public greenery areas. Maintenance of individual plots is shared by the city and the relevant urban districts.

2. The Research Aim

The research presented in this article focused on analysing and resolving current urban greenery issues, whether they apply to the city of Bratislava or are transcendent globally. The main goal was to assess the spatial and functional characteristics of current urban greenery in the city of Bratislava and to define maintenance measures and urban greenery renewal proposals with regard to the active participation of citizens.

Our research is based on a premise that the quality of urban greenery is enhanced by the city residents’ attitudes and demands. It defines the basic approaches that cities can take towards managing and planning vegetation, along with the scope, complexity, and their interests (from small-scale planning to large-scale planning, along with the inhabitants´ participation). Furthermore, this contribution gives examples of ways to use new technologies as part of a city´s communication with its inhabitants.

The current urban greenery condition is analysed and described with a special emphasis on the untapped potential of green areas on housing estates. Using examples from abroad, cases of successful revitalisation of urban greenery areas on housing estates are given, and the main problems faced by the selected region are assessed. The study gives examples of interactive online technology usage as a part of the city’s communication with its inhabitants. The possibility of the inhabitants’ participation in the creation of the city’s image through small green areas is considered for future urban greenery management. The inhabitants may markedly influence the quality of the urban environment. Therefore, our research emphasises the importance of motivating inhabitants and choosing communication methods efficiently with the view of accomplishing common goals. In addition, the research outcomes highlight the beneficial effect of appropriately defined urban planning management and strategies in order to create a higher-quality urban environment.

3. Methodology

Correct set-up and management of the residents’ activities may help them reach a common goal, but it is a challenge. When looking at cities from a human perspective, small green areas that find themselves in an inhabitant’s field of vision gain prominence. These include spaces that are visually perceived as greenery, although they are publicly inaccessible (private and semi-public spaces). These impulses can be embodied in multiple types of spaces [

43,

44,

45]. Following the philosophy of citizen participation in urban greenery creation, design, maintenance, and management, a workflow consisting of three main steps was proposed:

evaluation of the current urban greenery state (area size and spatial distribution of vegetation forms);

assessment of the availability and potential of urban greenery for citizens and management problems;

identification of small urban green areas and management of common urban greenery in Bratislava, together with a proposal of an interactive communication platform to improve participatory planning.

3.1. The Present State of the Urban Greenery in Bratislava

The proposal of formulating a typology of small green areas is based on problems the city currently faces. Analysing current trends, it tries to arrive at a solution by increasing the inhabitants’ participation. The proposal focuses on supporting the development of small green areas by choosing the right method of communication with the public. The proposal directly relies on inhabitants’ participation, which is why it is not possible to offer a scaled ground-plan solution.

To analyse the status of urban greenery, the classification presented in the city´s Greenery Master Plan 1999 was adopted. The plan distinguishes between public and private greenery, while public green spaces have three main categories:

Furthermore, areas with a total area of more than 0.5 ha and forests are included in the assessment with the following categories [ha]:

Eleven city districts were included in our assessment, where 93.22% of the total green area is located (out of which 74.68% were park areas, 89.63% were smaller landscaped areas, and 99.87% were estate greenery). They were also selected due to the high concentration of housing estates. At the same time, the majority of Bratislava’s population lives in these districts (97.5%). The evaluation presented in

Figure 2 includes the following city districts: Devínská Nová Ves, Dúbravka, Karlova Ves, Lamač, Nové Mesto, Petržalka, Podunajské Biskupice, Rača, Ružinov, Staré Mesto, Vrakuňa.

Geodata were processed in Quantum Geographic Information System (GIS) (QGIS) “Pi” π 3.14. A coordinate reference system, S-JTSK (Greenwich)/Krovak East North (EPSG code 5514) was set for all datasets. Online datasets provided by the national Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC) were accessed through the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) protocol using a WMS QGIS client. The following base maps for the urban areas and vegetation analyses were downloaded from the websites:

Open Street Maps:

http://tile.openstreetmap.org (accessed on 27 October 2022) using Data Source Manager XYZ connections [

47]. The map tiles in the “standard style” at

www.openstreetmap.org (accessed on 27 October 2022) are a produced work by the OpenStreetMap Foundation using OpenStreetMap data under the Open Database License.

3.2. Availability of Urban Greenery for Citizens, Its Potential and Problems of Management

Following the European Common Indicators Project (1999–2003) [

48], for the urban greenery formations that are larger than 0.5 ha, we need to reach the availability for citizens of 300 m. Therefore, a buffer zone of 300 m with a centre inside the urban green formations of forests, parks, and housing estates, which reach sizes of up to 0.5 ha, was created. Other authors [

49,

50] applied this methodology using other distances to assess the vegetation from a broader perspective. Considering the target aim of this article, we selected a 300 m distance availability for Bratislava’s citizens.

The ground material for the assessment of the greenery management problems was provided by the Bratislava Municipal Authority using email communication and a questionnaire. The outputs of the field survey were used to develop a definition of the problems related to planning and maintaining Bratislava’s greenery. Data were processed in Autocad application using a background map of Open Street Maps.

3.3. Identification of Small Urban Green Areas and an Interactive Communication Platform for Participators Planning of Small Urban Green Areas

The article provides a proposal of how to solve some problems with the maintenance and management of the urban greenery in this methodical step. The urban greenery investigation concentrated on small green areas and their contribution to the quality of city life, and appraised current trends as well as the potential of developing this type of vegetation in the city environment. A typology of small green areas in Bratislava was developed to follow the philosophy of both climate change adaptation needs and human factor needs. The proposal to formulate a typology reflects the problems that the city currently faces. As the issue concerns private and semi-public spaces, the municipality should strive to point the public in the right direction, namely the inhabitants and the private sector, as these are authorised to create and design such areas.

3.3.1. A Typology of Urban Green Areas

The drawn-up typology indicated five types of small green areas (

Figure 3).

Despite their spatial limitations, small green areas are largely beneficial to their inhabitants. They can enhance the environment, improve social interactions, and help create an attractive city. By combining small green areas into a single system, a new system of greenery can be created, one that would support other types of greenery.

3.3.2. Participating Actors Designing and Managing Small Green Areas

The proposed five types of small green vegetation areas might be managed by three kinds of actors in three different spaces:

residents—private spaces (balconies, front gardens, and courtyards);

small and medium-sized companies—commercial working private spaces (interiors);

enterprises, organisations—private spaces (interiors) and semi-private on a street.

3.3.3. Rules for Communication Platform Providing Participatory Planning and Management of Small Green Areas

The proposed rules revolve around establishing a communication platform—an online website and application that covers the greenery issue in the city of Bratislava, which serves as a tool for pointing the public in the right direction, and would be based on the following rules for supporting city life:

soft building/exterior transitions;

active streets and ground floors;

social interactions;

new opportunities to meet, stop, and stay, and experience new things and be comfortable.

The given rules are a skeleton for the planned interactive online platform, which we proposed in the results.

4. Results

4.1. Analysis and Evaluation of the Bratislava´s Urban Greenery Status

The city of Bratislava represents a typical urban area made of a variety of land use forms and different urban structures that determine the location of green spaces.

Urban greenery in Bratislava covers 220 m

2/inhabitant, which represents a 40% share of green space in relation to the total area of the city. When compared to other European cities (

Figure 4), this is well above average (Helsinki 99.1 m

2/capita; Dublin 40.3 m

2/capita; Birmingham 46.5 m

2/capita; Antwerp 67.2 m

2/capita; Zurich 108.5 m

2/capita; Leipzig 59.9 m

2/capita). Cities comparable to Bratislava in terms of population were included in the comparison and historical development.

However, experts point out a fundamental problem: 91% of green space is made up of forests (represented by the massif of the Little Carpathians) and only 9% of it is parks and landscaped areas. The forests, which represent recreational potential, are located mainly in the north of the territory. The majority of green spaces are covered by forest, as mentioned, and much less of them are situated in the inner city. Problems are also linked to the uneven distribution and quality of green areas. The diagram of green space distribution in the city confirms this (see

Figure 5).

4.2. Assessment of the Accessibility of Urban Greenery for Citizens, Its Potential and Identification of the Management Problems

The green area size factor is less important than greenery spatial distribution, as displayed in

Figure 5. According to the European Common Indicators Project, for an area of urban green space greater than 0.5 ha, accessibility is 300 m. For this value, urban green space cannot cover the built-up area of Bratislava, while parks and landscaped areas with a citywide recreational function include parks in several municipal districts (Dúbravka, Karlova Ves, Nové Mesto, Petržalka, Ružinov, Staré Mesto, Vrakuňa) (see

Figure 6).

After forests, the largest share of urban greenery is occupied by housing estate greenery (at mass residential constructions’ inner blocks), which is linked to the building of housing estates in the 1960s–1980s. When the urban greenery of housing estates was considered, then we could see a partial overlap with the vegetation of parks but a mainly extensive area of the urban greenery accessible to citizens living in municipal districts of Bratislava (Devínska Nová Ves, Dúbravka, Karlova Ves, Lamač, Nové Mesto, Petržalka, Podunajské Biskupice, Rača, Ružinov, Staré Mesto, Vrakuňa) (

Figure 7).

Green areas in Bratislava’s housing estates do not constitute functional urban green areas. However, looking at the city from the perspective of its potential, there is room for development (

Figure 8).

To obtain expert opinions and views representing the City Council and individual Municipal Districts of the City of Bratislava, email communication and replying to questionnaires were employed (

Box 1). Questionnaires were sent to representatives of all 17 municipal districts. 11 district representatives answered.

Box 1. A Questionnaire for city districts

Q1. How do you evaluate the urban green spaces in your district (e.g., are there Revitalization projects, do you see progress compared to 2016 or 2015)?

Q2: Do you have plans specifically for the housing estate green spaces (courtyards) that are in your management?

Q3: Do you, as a city district, try to involve residents in activities related to the creation or care of greenery? If yes, how?

Q4: How do you evaluate the cooperation with the city council in the maintenance and care of greenery and in the planning of new projects (positives, negatives, where do you see improvement?)

4.3. Identification of Small Green Areas and a Proposal of an Interactive Communication Platform for Citizens of Bratislava to Improve the Participatory Urban Greenery Management

The created typology presented in

Figure 3 and

Supplement S1 shows five types of small green spaces managed in three levels:

Residents—private premises (three types)

Businesses—workspaces (one type)

Businesses—street (one type)

Five types of spaces, such as balconies, front gardens, courtyards, streets, and interiors, are related to residents (types 1–3) and to businesses (type 4 and 5). The first three types are associated with sub-analyses; the last two types are left at the theoretical level.

The first type of small green space is the balcony (or loggia), which is an area that is connected to the living space. For a better idea, the research presents an analysis of balconies and loggias in a typified mass housing estate construction implemented in the 20th century. The floor plans indicate the residential units, and the flats are divided into two groups:

The number of balconies for each building type is then calculated for one building. According to the implemented types for each housing estate, we get an approximate idea of the number of balconies and loggias. In general, it can be stated that in most of the dwelling types, there are also balcony spaces. The same rule applies to the construction of new residential buildings. The potential of this type of space is, therefore, high.

The front garden is the exterior green space in front of the facade of the building. Analysis showing selected types of front gardens shows that this type of space has been implemented at each apartment building, differing only in the plan shape. The current use of front gardens varies depending on the occupants of the blocks of flats; some are used as allotments, others are left untended and planted with native trees (generally shrubby forms, Pinus and Betula) leaving only grassland. The analysis gives an approximate idea of the amount of this type of space, and as front gardens are also associated with existing non-typical buildings, we can conclude a high untapped potential.

The third type of small green space is the courtyard located as part of the historic.

19th-century town centre development. Courtyards or other private and semi-public spaces can contribute to completing the network of green spaces in a compact city, if the conditions of their use are set appropriately.

Street space is essential in creating a living city and is particularly related to the ground floor of buildings. Situating café terraces and creating transparent walls and shopfronts, all of this is attractive and lively and creates the genius loci of the place. The ground-floor parterres of the pedestrian roads are mostly owned by private entities, therefore, the street also targets this group.

The creation of interior greenery is a current trend; for the integrity of the design, it is therefore advisable to include areas of interior greenery, as these also depend on private motivation. Interior green areas do not only include the interior of the dwelling; they also represent the green working interiors. Interior greenery in office spaces has a number of positive effects on employees. Motivating companies to create green interiors is equally important as motivating occupants to create sustainable green spaces.

Small green area development is based on proper communication with the public, namely an online website and mobile application covering the greenery issue in the city of Bratislava. In this context, the way the information is given is much more important than just giving information. For that reason, the following proposal is focused on creating a website, including an interactive map for citizens (see

Supplement S2).

The interactive map may have the following functions:

If we can raise the greenery idea correctly via a web platform (with an interactive map) using a relevant web design, the simple utilisation of such a web platform would be motivation. The web page will consist of parts addressed to (1) residents and (2) tourists (

Supplement S2).

Residents may interact with the proposed website with activities, which are stressed in the following points:

Citizens can upload their presentations of green areas directly into the map together with photos. By doing so, a network of private green areas will be developed.

Companies can upload information on green areas developed for citizens or employees within company profiles.

To bring together all activities, non-governmental organisations, and information on urban green areas without distinction of rights (powers)—to make information easier to access for the wide public.

Fund raising: the project idea definition and searching for funding.

Searching for volunteers: the possibility of establishing voluntary activities when developing small green areas.

Professional background: professional consultancy on urban greenery issues.

Up-to-date information: advice and tips for spreading urban greenery awareness.

Tourists may interact with the proposed website with activities, which are stressed in the following points:

Information on the map about attractions for tourists and possibility for leisure activities in the already developed green public spaces. The map illustrating the urban green places network (public or private) is one of the web page outputs. By using this map, citizens can find leisure places and also become more familiar with new green spaces. Furthermore, the map can be helpful for tourists searching for information on interesting urban places.

Involvement in the communal activities.

5. Discussion

The development of a green infrastructure is defined by the city’s strategy. The question is whether the 1999 Greenery Master Plan is sufficient in its non-digital form, considering the comprehensive view of zones required by the issue. When considering the share of green areas in the urbanised territory, the second largest urban greenery share after forests is represented by housing estate greenery. As an undeveloped area where no future construction is planned, housing-estate greenery could serve as a fundamental land source for the implementation of the green infrastructure policy, the systemic combination of green areas into green belts, and for connecting the city’s built-up areas with surrounding rural zones.

Housing estates have been constructed as comprehensive, independent, and self-sufficient units with their own social infrastructure, recreational greenery, sports, and leisure places. They are based on the Athens Charter, which means that housing blocks are located at greater distances in such a way that there are a lot of open spaces between blocks. Thanks to the implementation of Athens Charted guidelines, we can benefit from open spaces available for both urban greenery and social infrastructure—called courtyards (

Supplement S1). The dysfunctional nature of courtyards is nothing new; this criticism has been levied since the 1960s. The courtyards’ potential has remained untapped for over 40 years. In practice, although its potential is not always crucial; funding and its quantity tend to be the deciding factors.

The urban greenery development potential for the city of Bratislava can be implemented in future urban planning documentation. When engaged in small-scale planning on a city-wide level, we are talking about big projects where planning and implementation come at considerable expense. Based on a questionnaire survey performed with the Municipal Authority, we can sum up the following problems related to planning and maintaining Bratislava’s greenery:

- (1)

No current strategic documentation concerning greenery (e.g., a Greenery Master Plan);

- (2)

Unregistered property-law relations;

- (3)

Insufficient personnel;

- (4)

Fragmented competences in city administration.

The urban greenery issues are specified in detail below:

(1) Thanks to EU subsidies, the Municipal Authority has managed to build new parks with regard to long-term urban greenery planning and maintenance. However, a vision is needed that would exceed the obligations imposed by measures for climate change adaptation. The issue of climate change is pivotal, therefore requiring investment in terms of time and funding. There is no room left to address other problems, such as for instance to develop a new Greenery Master Plan for the city of Bratislava. Bratislava lacks a general concept for greenery planning, and there is no map of green areas with recorded ownership. It works by mapping green areas located on plots that are owned by the city. The creation and maintenance of greenery are governed by the effective urban planning documentation of the city and its zones, including general binding regulations on public greenery.

(2) When formulating greenery policies under the umbrella of urban planning, it is necessary to become familiar with all green areas and be aware of their functions, as well as relevant ownership. Green areas are often divided among private owners as a consequence of restitution and the process of returning property to its original owners. This is the reason why urban greenery areas are frequently divided by a floor plan of former plots. Information regarding the ownership of plots is publicly available, but there is no unified digital urban greenery map, which would show proprietary rights to plots.

(3) Insufficient personnel is another issue—simply put, there are no people in place to come up with the required strategies and projects. The Municipal Architect’s Office employs six people, whereby three of them are in charge of the current project schemes. Comparing this with the Municipal Architect’s Office of the City of Brno in the Czech Republic which has 25 employees, four trainees and four employees in charge of public spaces, and three others responsible for communication with the public.

(4) There is no such policy in existence, and no unified policy that deals with greenery as a matter of priority. In practice, there is a problem with fragmented competencies where urban districts manage and handle their greenery by themselves; the same goes for the greenery administered by the Municipal Authority. The problem is with splitting competences as well as property issues. As already mentioned, Bratislava is divided into 17 districts, which also administer public greenery areas. The maintenance of individual plots is shared by the city and the relevant urban districts. The project of Renewed Land Registry was concluded in the districts, with many plots passing into the ownership of third parties. This divided formerly unified courtyards in terms of greenery maintenance. First, it is necessary to resolve material issues, and then discuss greenery and plot maintenance with the city. Then, the Municipal Authority will be able to address the issue of courtyard greenery in a comprehensive manner, assuming that it will still be managed, or rather owned, or subjected to another type of ownership by the urban district.

With regard to cooperation between city districts and the Municipal Authority, all districts have a neutral or negative attitude. Therefore, planning and executing projects under a city-wide policy is currently just a future vision. Although the largest green areas in Bratislava are located on housing estates, the city does not pay any particular attention to housing-estate greenery, although the strategy does mention it. The lack of statistical data is also surprising. There is no division that covers all greenery-related activities in the city or keeps statistics on the success of projects and executed revitalisations. Information concerning implemented projects related to urban greenery can only be gained by studying documents, reports, and budgets published on websites. However, the questionnaire survey confirmed that there is no comprehensive approach or progress evaluation made over a specific time period.

As the issue concerns private and semi-public spaces, the city should strive to point the public in the right direction, namely the inhabitants and the private sector, as these are authorised to create such areas. Considering the area size of the three urban greenery categories that was evaluated per inhabitant in the municipality districts of Bratislava, we can conclude that the recommended limits are fulfilled. The standards of the minimum surface area parameters for greenery are specified according to land use (housing estate greenery, family houses, courtyard greenery, etc.). There is a recommendation that surface area for a central park should be 10 ha per 100,000 inhabitants and surface area for courtyards as well as for parks near housing estates should range from 10 m

2 to 17 m

2 per inhabitant. When taking into account the calculation of greenery size area parameters for the individual Bratislava municipalities, it is evident that the minimum standard of 10m

2 per inhabitant has been reached (the average is 17.41 m

2) (

Figure 2). As is shown in

Figure 1, Bratislava urban greenery covers 40% of greenery out of the total Bratislava city area. When compared to other European cities, it indicates that Bratislava is “high above average”. The main problem is not the area size and extension of the vegetation in the city, but problems are linked with uneven urban greenery distribution over the city (

Figure 5), its accessibility (

Figure 6), as well as its quality. The greenery policy should introduce a plan to transform the dysfunctional areas and decide on their function for the city, as we suggested in the potential for urban greenery development (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8), as well as on priorities. The placement of replacement plants would also be governed by this type of policy.

6. Conclusions

As an EU member state, Slovakia has undertaken the task of addressing the climate change issue, and this is reflected in national policies and strategies. In 2014, the Slovak Republic’s Adaptation Strategy on the Adverse Impacts of Climate Change was published [

52], with the aim of providing information for the adaptation process and coordination mechanisms. The adaptation strategy was supposed to define the framework for the intended measures. It emphasises the sustainable development of cities, stipulated by Act No. 17/1992, Collection of Laws on the Environment, and concerns a development that would safeguard the ability of present and future generations in meeting their basic life necessities, while maintaining nature’s diversity as well as the natural functions of ecosystems [

53,

54,

55]. The adaptation strategy’s aim was to decrease the impact of climate change on the city life, to prepare for extremes, and draw up strategies for dealing with and reducing them. In the interest of sustainable development, the emphasis is placed on alternative energy sources or supporting public transport and biodiversity.

Managing greenery in an urban environment and its role in addressing the multiple problems society currently faces are very topical issues not only in Slovakia, but globally. Cities in this century should be more environment-friendly and healthy for their inhabitants.

Many large European cities and elsewhere have been formulating concepts in the long term regarding developing greenery, involving inhabitants, and inspiring them to work with the city administration to meet the aims set by urban planning [

56]. Therefore, the interactive online presentation of the Smart Green City was proposed. The proposed website would offer the possibility to present the urban greenery becoming a new attribute of quality of the city. With the help of available information, the implementation of appropriate examples can accelerate the implementation of other urban greenery projects as well as the motivation of resident and tourists to participate in the design and management of the urban greenery.

Bratislava, as one of the largest cities in Slovakia, is exposed to the need to address the concept of green space development not only in the context of adaptation mechanisms to climate change but also with regard to its aesthetic and psychological functions for the inhabitants of the city.

With the above-mentioned main objective, the purpose of the presented contribution is to look for new trends in the use of greenery in the urban environment to compare the situation in the past and at present, present new possibilities for the use of urban spaces, and present new possibilities for the design of greenery with the help of commercial contractors.

By means of the design of a supporting system of green spaces in small areas to the overall green space system and by means of a typology of these small spaces, it is necessary to define its potential in the designed area. The proposal to create a new system of private and semi-public green spaces to serve as a complement to the existing public green space system appears to be one of the possible and promising solutions.

Graphical presentation of the different types of small spaces and examples of communication methods with residents towards a better municipal policy on green spaces in the city qualitatively enriched the proposed solutions. At the same time, they represent a significant contribution of the research.

On the range of proposed solutions offered for small green spaces in Bratislava and participation of citizens are joined by issues related to their financing and the implementation of municipal city policy in this area.