Understanding the Antecedents of Use of E-Commerce and Consumers’ E-Loyalty in Saudi Arabia Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

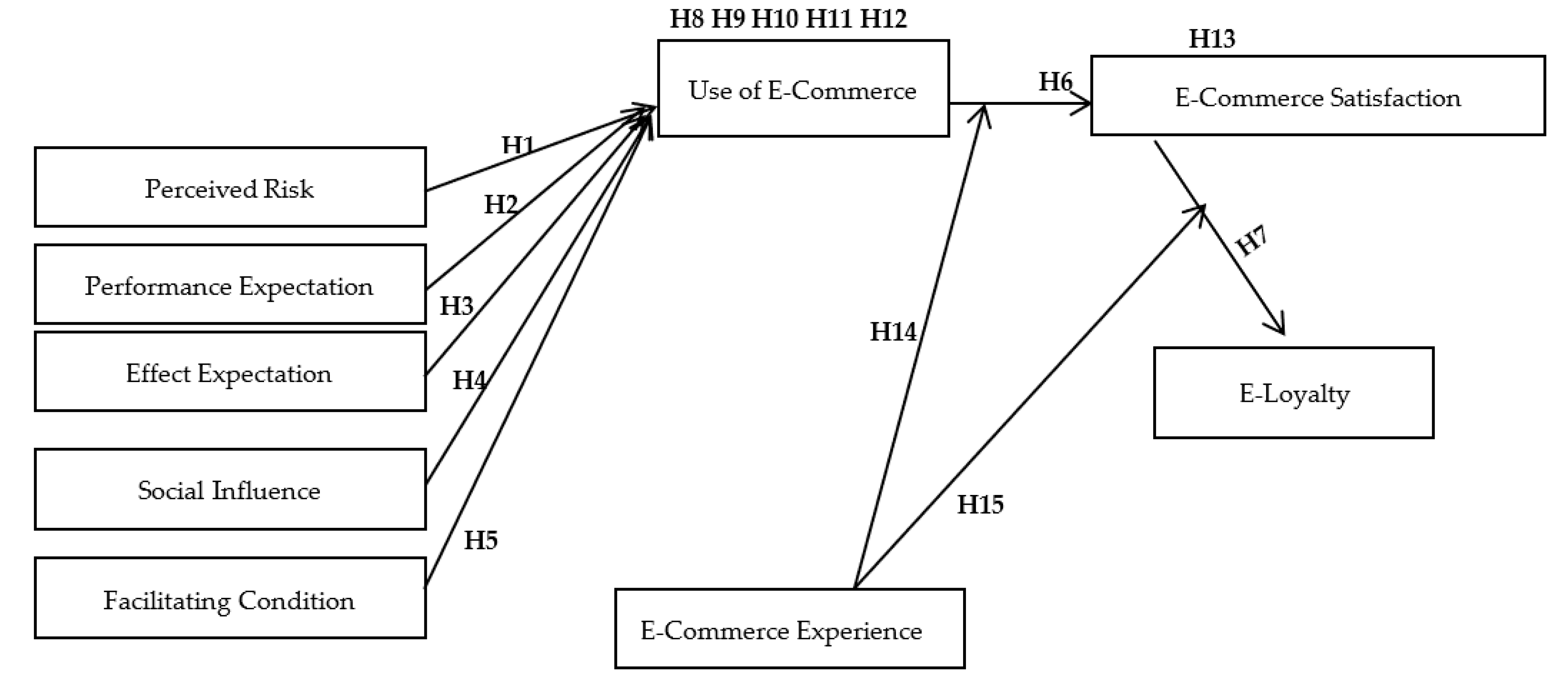

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. E-Loyalty

2.2. Perceived Risk and UEC

2.3. Performance Expectation and UEC

2.4. Effect Expectation and UEC

2.5. Social Influence and UEC

2.6. Facilitating Condition and UEC

2.7. UEC and E-commerce Satisfaction

2.8. E-Commerce Satisfaction and E-Loyalty

2.9. The mediating role of Customer UEC

2.10. Mediating Role of E-Commerce Satisfaction

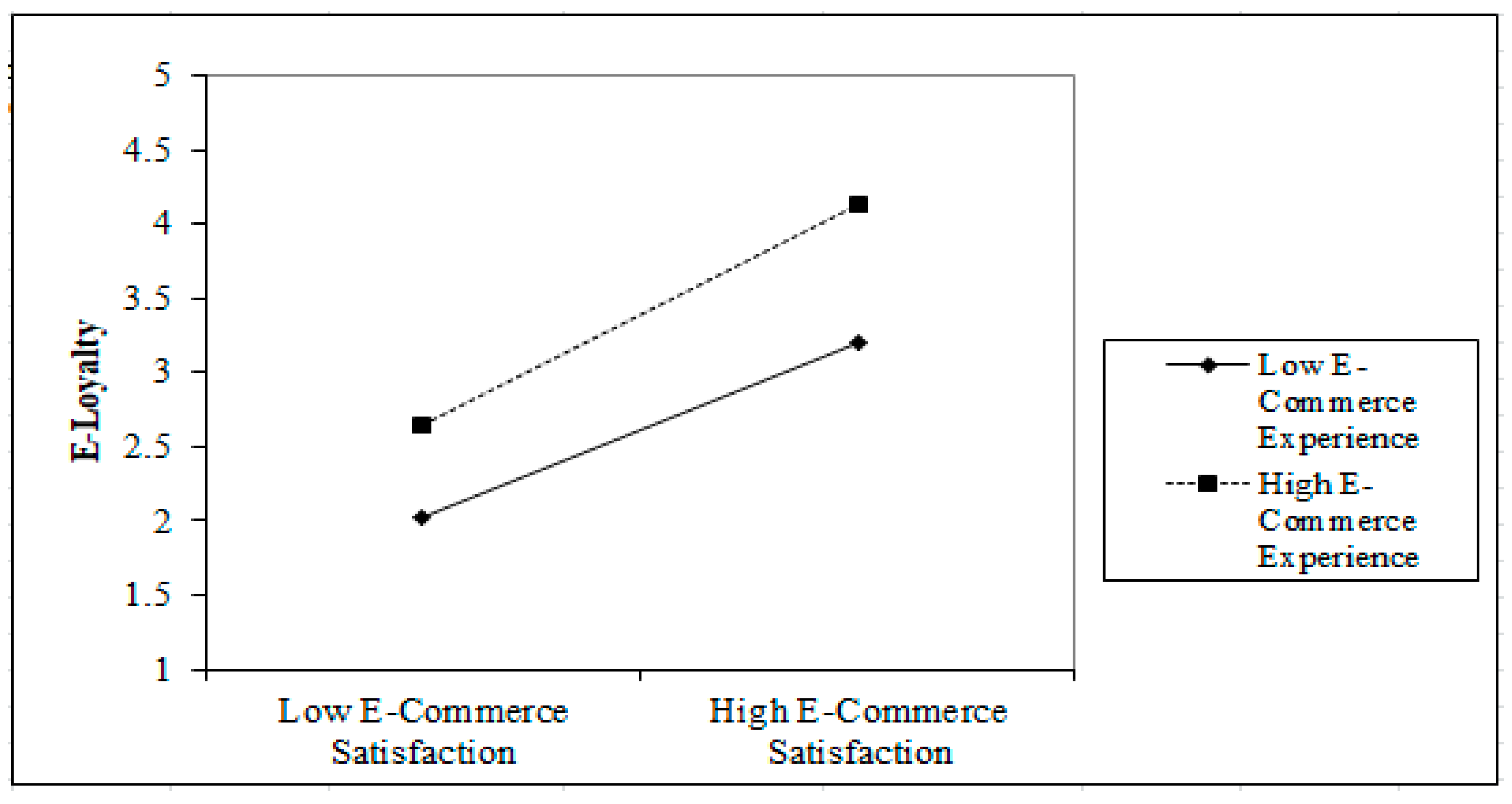

2.11. Moderating Role of E-Commerce Experience

2.12. Theoretical Background

3. Sample and Procedure

3.1. Measures

3.2. Data Analysis Method

3.3. Common-Method Variance Bias Test

3.4. Respondents’ Profile

3.5. Mean Values, and Correlation of the Study Variables

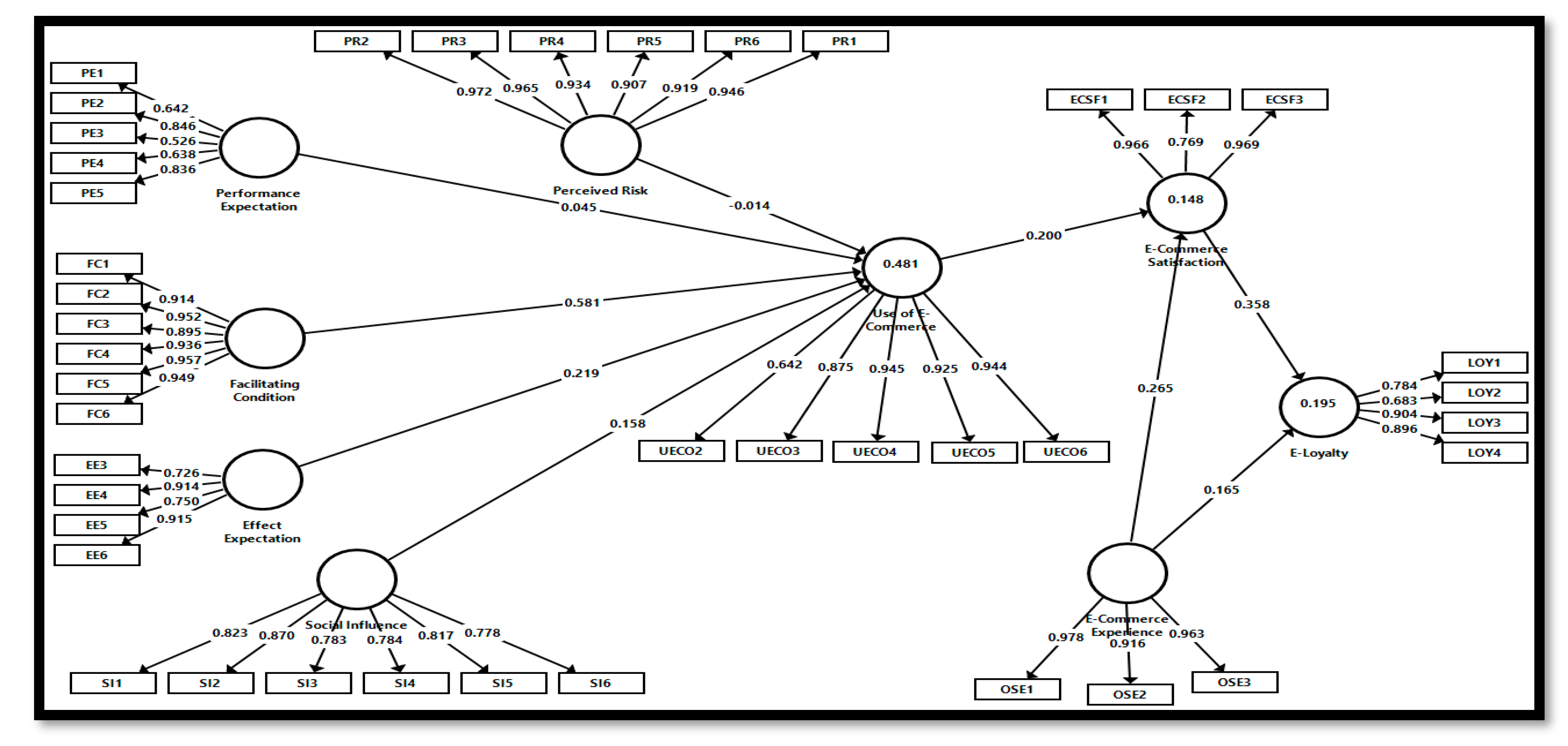

3.6. Evaluation of Measurement Model (Outer Model)

3.7. Assessment of Structural (Inner) Model

3.8. Hypotheses Testing

3.9. Tests for Mediation

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Practical Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Azam, A. The effect of website interface features on e-commerce: An empirical investigation using the use and gratification theory. Int. J. Bus. Inf. Syst. 2015, 19, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhou, T.; Wang, M. Information and communication technology (ICT), digital divide and urbanization: Evidence from Chinese cities. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Bonilla, F.; Gijón, C.; De la Vega, B. E-commerce in Spain: Determining factors and the importance of the e-trust. Telecommun. Policy 2022, 46, 102280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofokeng, T.E. The impact of online shopping attributes on customer satisfaction and loyalty: Moderating effects of e-commerce experience. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1968206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Azzawi, G.A.; Miskon, S.; Abdullah, N.S.; Ali, N.M. Factors Influencing Customers’ Trust in E-commerce during COVID-19 Pandemic. In Proceedings of the 2021 7th International Conference on Research and Innovation in Information Systems (ICRIIS), digital, 25–26 October 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatti, A.; Akram, H.; Basit, H.M.; Khan, A.U.; Raza, S.M.; Naqvi, M.B. E-commerce trends during COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Future Gener. Commun. Netw. 2020, 13, 1449–1452. [Google Scholar]

- Eid, M.; Al-Anazi, F.U. Factors influencing Saudi consumers loyalty toward B2C E-commerce. In Proceedings of the AMCIS 2008 Proceedings, Toronto, ON, Canada, 14–17 August 2008; p. 405. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, R. The role of self-efficacy and customer satisfaction in driving loyalty to the mobile shopping application. International. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2018, 46, 283–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, J.M.; Varki, S.; Rosen, D.E. Loyalty and its antecedents: Are the relationships static? J. Relatsh. Mark. 2010, 9, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichheld, F.F.; Schefter, P. E-loyalty: Your secret weapon on the web. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2000, 78, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Brilliant, M.A.; Achyar, A. The impact of satisfaction and trust on loyalty of e-commerce customers. ASEAN Mark. J. 2012, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, W.; Hussain, A.; Farhat, K.; Arif, I. Underlying factors influencing consumers’ trust and loyalty in E-commerce. Bus. Perspect. Res. 2020, 8, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.M.; Chang, C.C.; Cheng, H.L.; Fang, Y.H. Determinants of customer repurchase intention in online shopping. Online Inf. Rev. 2009, 33, 761–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence consumer loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63 (Suppl. 4), 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, W.D. Satisfaction is nice, but value drives loyalty. Mark. Res. 1999, 11, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Valvi, A.C.; Fragkos, K.C. Critical review of the e-loyalty literature: A purchase-centred framework. Electron. Commer. Researc 2012, 12, 331–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Srinivasan, S.S.; Anderson, R.; Ponnavolu, K. Customer loyalty in e-commerce: An exploration of its antecedents and consequences. J. Retail. 2002, 78, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naami, T.; Anesbury, Z.W.; Stocchi, L.; Winchester, M. How websites compete in the Middle East: The example of Iran. J. Consum. Behav. 2022, 21, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. E-commerce websites, consumer order fulfillment and after-sales service satisfaction: The customer is always right, even after the shopping cart check-out. J. Strategy Manag. 2021, 15, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdim, K.; Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C. The role of utilitarian and hedonic aspects in the continuance intention to use social mobile apps. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C.; Yen, D.C.; Hwang, M.I. Factors influencing the continuance intention to the usage of Web 2.0: An empirical study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langga, A.; Kusumawati, A.; Alhabsji, T. Intensive distribution and sales promotion for improving customer-based brand equity (CBBE), re-purchase intention and word-of-mouth (WOM). J. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2020, 37, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pebriani, W.V.; Sumarwan, U.; Simanjuntak, M. The effect of lifestyle, perception, satisfaction, and preference on the online re-purchase intention. Indep. J. Manag. Prod. 2018, 9, 545–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garaus, M. Atmospheric harmony in the retail environment: Its influence on store satisfaction and re-patronage intention. J. Consum. Behav. 2017, 16, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, S.; Amin, M.; Ismail, W.K.W. Online repatronage intention: An empirical study among Malaysian experienced online shoppers. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2014, 42, 390–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, G. When does commitment lead to loyalty? J. Serv. Res. 2003, 5, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, M.; Limayem, M.; Liu, V. Online customer stickiness: A longitudinal study. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. (JGIM) 2002, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.Y.; Parks, S.C. The relationship between restaurant service quality and consumer loyalty among the elderly. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2001, 25, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2013, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.H.; Hsieh, Y.C.; Hsu, C.N. Adding innovation diffusion theory to the technology acceptance model: Supporting employees’ intentions to use e-learning systems. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2011, 14, 124–137. [Google Scholar]

- Alalwan, A.A.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Rana, N.P. Factors influencing adoption of mobile banking by Jordanian bank customers: Extending UTAUT2 with trust. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shaikh, A.A.; Karjaluoto, H. Mobile banking adoption: A literature review. Telemat. Inform. 2015, 32, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wessels, L.; Drennan, J. An investigation of consumer acceptance of M-banking. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2010, 28, 547–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghalandari, K. The effect of performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence and facilitating conditions on acceptance of e-banking services in Iran: The moderating role of age and gender. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 2012, 12, 801–807. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, S.; Lehto, X.Y.; Park, J. Travelers’ intent to use mobile technologies as a function of effort and performance expectancy. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2009, 18, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. An empirical analysis of the antecedents of electronic commerce service continuance. Decis. Support Syst. 2001, 32, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, R.P.; Seth, D.; Mukadam, S. Quality dimensions of e-commerce and their implications. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2007, 18, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayad, R.; Paper, D. The technology acceptance model e-commerce extension: A conceptual framework. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 26, 1000–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pradana, M.; Ichsan, M. Analysis of an indonesian e-commerce website: Gap between actual performance and users’ expectation. J. Manaj. Dan Bisnis Indones. 2018, 6, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, I.G.N.S.; Triandini, E.; Kabnani, E.T.G.; Arifin, S. E-commerce website service quality and customer loyalty using WebQual 4.0 with importance performances analysis, and structural equation model: An empirical study in shopee. Regist. J. Ilm. Teknol. Sist. Inf. 2021, 7, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Nguyen, H.V.; Nguyen, H.; Tran, V.T.; Nguyen, T.H. Consumer attitudes toward facial recognition payment: An examination of antecedents and outcomes. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2021, 40, 511–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.C.; Chiou, J.S. The impact of perceived ease of use on Internet service adoption: The moderating effects of temporal distance and perceived risk. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Prybutok, G.; Peng, X.; Prybutok, V. Determinants of trust in health information technology: An empirical investigation in the context of an online clinic appointment system. Int. J. Hum. –Comput. Interact. 2020, 36, 1095–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, I.O.; Pateli, A.G.; Giannakos, M.N.; Chrissikopoulos, V. Moderating effects of online shopping experience on customer satisfaction and repurchase intentions. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2014, 42, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagger, T.S.; O’Brien, T.K. Does experience matter? Differences in relationship benefits, satisfaction, trust, commitment and loyalty for novice and experienced service users. Eur. J. Mark. 2010, 44, 1528–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.M.; Ku, B.P. Moderating effects of voluntariness on the actual use of electronic health records for allied health professionals. JMIR Med. Inform. 2015, 3, e2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sarason, I.G.; Sarason, B.R.; Pierce, G.R. Social support: The search for theory. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1990, 9, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.P.; Ho, Y.T.; Li, Y.W.; Turban, E. What drives social commerce: The role of social support and relationship quality. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2011, 16, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hajli, M.N. The role of social support on relationship quality and social commerce. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2014, 87, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attar, R.W.; Shanmugam, M.; Hajli, N. Investigating the antecedents of e-commerce satisfaction in social commerce context. Br. Food J. 2020, 123, 849–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Rashidin, M.S.; Song, F.; Wang, Y.; Javed, S.; Wang, J. Determinants of Consumer’s Purchase Intention on Fresh E-commerce Platform: Perspective of UTAUT Model. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211027875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, S.; Gupta, S.; Bhatt, R. A study of relationship among service quality of E-commerce websites, customer satisfaction, and purchase intention. Int. J. E-Bus. Res. (IJEBR) 2020, 16, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dospinescu, O.; Dospinescu, N.; Bostan, I. Determinants of e-commerce satisfaction: A comparative study between Romania and Moldova. Kybernetes 2021, 51, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.G.; Lin, H.F. Customer perceptions of e-service quality in online shopping. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2005, 33, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, S.; Ertz, M.; Jo, M.; Sarigöllü, E. Factors affecting customer satisfaction on online shopping holiday. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2021, 3, 516–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, K.; Ali, M.L.; Gai, K.; Qiu, M. Information security policy for e-commerce in Saudi Arabia. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Big Data Security on Cloud (BigDataSecurity), IEEE International Conference on High Performance and Smart Computing (HPSC), and IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Data and Security (IDS), New York, NY, USA, 9–10 April 2016; pp. 187–190. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L.; Charles, V. The impact of consumers’ perceptions regarding the ethics of online retailers and promotional strategy on their repurchase intention. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 57, 102264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, S.; Mohsen, K.; Tsimonis, G.; Oozeerally, A.; Hsu, J.H. M-commerce: The nexus between mobile shopping service quality and loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.W.; Huang, R.T.; Huang, R.T. The relationships among trust, e-satisfaction, e-loyalty, and customer online behaviors. Int. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2015, 1, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R.E.; Srinivasan, S.S. E-satisfaction and e-loyalty: A contingency framework. Psychol. Mark. 2003, 20, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribbink, D.; Van Riel, A.C.R.; Liljander, V.; Streukens, S. Comfort your online customer: Quality, trust and loyalty on the Internet. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2004, 14, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hendrawan, G.M.; Agustini, M.Y.D.H. Mediating Effect of e-Satisfaction and Trust on the Influence of Brand Image and e-Loyalty. J. Manag. Bus. Environ. 2021, 3, 10–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.C.; Goode, M.M. The four levels of loyalty and the pivotal role of trust: A study of online service dynamics. J. Retail. 2004, 80, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vun, A.C.Y.; Harun, A.; Lily, J.; Lasuin, C.A. Service quality and customer loyalty: The mediating role of customer satisfaction among professionals. Int. J. Online Mark. (IJOM) 2013, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rose, S.; Hair, N.; Clark, M. Online customer experience: A review of the business-to-consumer online purchase context. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jin, B.; Swinney, J.L. The role of etail quality, e-satisfaction and e-trust in online loyalty development process. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2009, 16, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentina, I.; Amialchuk, A.; Taylor, D.G. Exploring effects of online shopping experiences on browser satisfaction and e-tail performance. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2011, 39, 742–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, M.; Liu, V. Online consumer retention: Contingent effects of online shopping habit and online shopping experience. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2007, 16, 780–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.; Cavallero, L.; Miranda, F.J. Fashion brands on retail websites: Customer performance expectancy and e-word-of-mouth. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.H.; Yen, C.H.; Chiu, C.M.; Chang, C.M. A longitudinal investigation of continued online shopping behavior: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Hum. -Comput. Stud. 2006, 64, 889–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao Suan Samuel, L.; Balaji, M.S.; Kok Wei, K. An investigation of online shopping experience on trust and behavioral intentions. J. Internet Commer. 2015, 14, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial least squares structural equation modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 26, pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Harman, H.H. Modern Factor Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, M. Cross-validatory choice and assessment of statistical predictions. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. 1974, 36, 111–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Fit Indices in Covariance Structure Modeling: Sensitivity to Underparameterized Model Misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Assessing mediation in communication research. In The Sage Sourcebook of Advanced Data Analysis Methods for Communication Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 13–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F.; Scharkow, M. The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: Does method really matter? Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Frequencies | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Course | ||

| Undergraduate | 267 | 79.9 |

| Post-graduate | 67 | 20.1 |

| Age | ||

| Up to 25 years | 296 | 88.6 |

| Above 25 years | 38 | 11.4 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 222 | 66.5 |

| Female | 112 | 33.5 |

| Family income (per month, SAR) | ||

| Less than 5000 | 188 | 56.3 |

| 25,000–40,000 | 117 | 350 |

| More than 40,000 | 29 | 8.70 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 PR | 1 | 3.5534 | ||||||||

| 2 PE | −0.373 ** | 1 | 2.5714 | |||||||

| 3 EE | −0.221 ** | 0.085 | 1 | 3.0481 | ||||||

| 4 SI | −0.043 | 0.131 * | 0.156 ** | 1 | 3.8591 | |||||

| 5 ECS | 0.127 * | 0.114 * | 0.337 ** | 0.256 ** | 1 | 2.9457 | ||||

| 6 E-Loyalty | −0.020 | −0.016 | 0.369 ** | 0.217 ** | 0.414 ** | 1 | 2.9264 | |||

| 7 FC | −0.102 | 0.141 ** | 0.134 * | 0.140 * | 0.189 ** | 0.387 ** | 1 | 3.4067 | ||

| 8 UEC | −0.135 * | 0.133 * | 0.308 ** | 0.260 ** | 0.253 ** | 0.353 ** | 0.564 ** | 1 | 3.3577 | |

| 9 ECE | −0.114 * | 0.233 ** | 0.254 ** | 0.129 * | 0.327 ** | 0.280 ** | 0.323 ** | 0.339 ** | 1 | 3.3811 |

| Variable | Loadings | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| E-commerce satisfaction | 0.932 | 0.821 | |

| ECSF1 | 0.966 | ||

| ECSF2 | 0.769 | ||

| ECSF3 | 0.969 | ||

| Effect Expectation | 0.898 | 0.691 | |

| EE3 | 0.726 | ||

| EE4 | 0.914 | ||

| EE5 | 0.750 | ||

| EE6 | 0.915 | ||

| Facilitating Condition | 0.976 | 0.872 | |

| FC1 | 0.914 | ||

| FC2 | 0.952 | ||

| FC3 | 0.895 | ||

| FC4 | 0.936 | ||

| FC5 | 0.957 | ||

| FC6 | 0.949 | ||

| E-Loyalty | 0.892 | 0.676 | |

| LOY1 | 0.784 | ||

| LOY2 | 0.683 | ||

| LOY3 | 0.904 | ||

| LOY4 | 0.896 | ||

| E-commerce Experience | 0.967 | 0.907 | |

| OSE1 | 0.978 | ||

| OSE2 | 0.916 | ||

| OSE3 | 0.963 | ||

| Performance Expectation | 0.830 | 0.502 | |

| PE1 | 0.642 | ||

| PE2 | 0.846 | ||

| PE3 | 0.526 | ||

| PE4 | 0.638 | ||

| PE5 | 0.836 | ||

| Perceived Risk | 0.979 | 0.885 | |

| PR2 | 0.972 | ||

| PR3 | 0.965 | ||

| PR4 | 0.934 | ||

| PR5 | 0.907 | ||

| PR6 | 0.919 | ||

| Social Influence | 0.919 | 0.656 | |

| SI1 | 0.823 | ||

| SI2 | 0.870 | ||

| SI3 | 0.783 | ||

| SI4 | 0.784 | ||

| SI5 | 0.817 | ||

| SI6 | 0.778 | ||

| UEC | 0.941 | 0.764 | |

| UECO2 | 0.642 | ||

| UECO3 | 0.875 | ||

| UECO4 | 0.945 | ||

| UECO5 | 0.925 | ||

| UECO6 | 0.944 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 E-commerce Experience | |||||||||

| 2 E-commerce satisfaction | 0.358 | ||||||||

| 3 E-Loyalty | 0.315 | 0.481 | |||||||

| 4 Effect Expectation | 0.206 | 0.246 | 0.346 | ||||||

| 5 Facilitating Condition | 0.337 | 0.205 | 0.429 | 0.095 | |||||

| 6 Perceived Risk | 0.118 | 0.137 | 0.109 | 0.193 | 0.105 | ||||

| 7 Performance Expectation | 0.288 | 0.208 | 0.152 | 0.228 | 0.185 | 0.390 | |||

| 8 Social Influence | 0.141 | 0.279 | 0.251 | 0.173 | 0.149 | 0.085 | 0.181 | ||

| 9 UEC | 0.365 | 0.287 | 0.405 | 0.321 | 0.601 | 0.147 | 0.187 | 0.286 |

| R Square | R Square | R Square Adjusted | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-commerce satisfaction | 0.148 | 0.143 | ||

| E-Loyalty | 0.195 | 0.191 | ||

| UEC | 0.481 | 0.473 | ||

| f Square | E-commerce satisfaction | E-Loyalty | UEC | |

| E-commerce Experience | 0.072 | 0.030 | ||

| E-commerce satisfaction | 0.141 | |||

| Effect Expectation | 0.088 | |||

| Facilitating Condition | 0.620 | |||

| Perceived Risk | 0.000 | |||

| Performance Expectation | 0.003 | |||

| Social Influence | 0.046 | |||

| UEC | 0.041 | |||

| Inner VIF Values | E-commerce satisfaction | E-Loyalty | UEC | |

| E-commerce Experience | 1.143 | 1.127 | ||

| E-commerce satisfaction | 1.127 | |||

| Effect Expectation | 1.053 | |||

| Facilitating Condition | 1.049 | |||

| Perceived Risk | 1.124 | |||

| Performance Expectation | 1.128 | |||

| Social Influence | 1.050 | |||

| UEC | 1.143 | |||

| Fit Summary | Test | Value | ||

| SRMR | 0.044 | |||

| NFI | 0.914 | |||

| Q-Square | SSO | SSE | Q² (=1-SSE/SSO) | |

| E-commerce satisfaction | 1002.000 | 887.000 | 0.115 | |

| E-Loyalty | 1336.000 | 1167.275 | 0.126 | |

| UEC | 1670.000 | 1186.493 | 0.290 |

| Relationships | Beta Value | T Value | p-Value | 5.0% CI | 95.0% CI | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 Perceived Risk -> UEC | −0.01 | 0.293 | 0.385 | −0.096 | 0.054 | Not Supported |

| H2 Performance Expectation -> UEC | 0.045 | 1.039 | 0.151 | −0.021 | 0.103 | Not Supported |

| H3 Effect Expectation -> UEC | 0.219 | 5.512 | 0.000 * | 0.150 | 0.276 | Supported |

| H4 Social Influence -> UEC | 0.158 | 3.319 | 0.001 * | 0.075 | 0.227 | Supported |

| H5 Facilitating Condition -> UEC | 0.581 | 16.410 | 0.000 * | 0.527 | 0.644 | Supported |

| H6 UEC -> E-commerce satisfaction | 0.200 | 5.103 | 0.000 * | 0.152 | 0.281 | Supported |

| H7 E-commerce satisfaction -> E-Loyalty | 0.669 | 3.284 | 0.001 * | 0.305 | 1.032 | Supported |

| Relationships | Beta | T Value | p-Value | 5.0% CI | 95.0% CI | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H8: PR -> UEC -> ECS | −0.003 | 0.267 | 0.395 | −0.020 | 0.013 | Not Supported |

| H9: PE -> UEC -> ECS | 0.009 | 0.858 | 0.196 | −0.005 | 0.028 | Not Supported |

| H10: EE -> UEC-> ECS | 0.044 | 3.551 | 0.000 * | 0.031 | 0.072 | Supported |

| H11: SI -> UEC -> ECS | 0.032 | 2.350 | 0.010 * | 0.014 | 0.054 | Supported |

| H12: FC -> UEC -> ECS | 0.117 | 4.985 | 0.000 * | 0.092 | 0.168 | Supported |

| H13: UEC -> ECS -> E-Loyalty | 0.135 | 2.552 | 0.006 * | 0.062 | 0.233 | Supported |

| Relationships | Beta | T Value | p-Value | 5.0% | 95.0% | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H14: UEC*ECE -> ECS | −0.024 | 0.235 | 0.407 | −0.208 | 0.122 | Not Supported |

| H15: ECS*ECE -> E-Loyalty | 0.077 | 1.699 | 0.046 | 0.155 | 0.006 | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Algamash, F.A.; Mashi, M.S.; Alam, M.N. Understanding the Antecedents of Use of E-Commerce and Consumers’ E-Loyalty in Saudi Arabia Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14894. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214894

Algamash FA, Mashi MS, Alam MN. Understanding the Antecedents of Use of E-Commerce and Consumers’ E-Loyalty in Saudi Arabia Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability. 2022; 14(22):14894. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214894

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlgamash, Fahad Ali, Munir Shehu Mashi, and Mohammad Nurul Alam. 2022. "Understanding the Antecedents of Use of E-Commerce and Consumers’ E-Loyalty in Saudi Arabia Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic" Sustainability 14, no. 22: 14894. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214894