1. Introduction

Sustainability is an issue that is attracting increased interest. New operating models appear all the time (e.g., stores where one can buy products without packaging—“zero waste stores”), aimed at reducing the negative impact of man on the environment. One of the most important models is the circular economy (CE). The CE concept is based on the idea that materials, raw materials and products return to the production process and become a basis for new products and services. In an ideal model, no waste is generated and manufactured products in good condition are reused by market players [

1,

2]. Moreover, according to global challenges, defined by European governments in the field of sustainable consumption, European citizens have to change their consumption models to those that are less oppressive for the environment. There are some social concepts that respond to described circumstances. One of them is a freeshop.

A freeshop is a place where one may leave things that are in a good condition but useless for him/her—such as too small clothes, books that have been read, etc. On the other hand, one can take items left by other visitors that one finds useful. The idea corresponds to the problem of climate challenges defined—among others—by The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the Ellen McArthur Foundation as excessive consumption. An example of a highly developed Polish freeshop is Podzielnia in the city of Poznań, Poland (More:

https://podzielnia.pl/in-english/; Other examples are: Free Shop KDW Warsaw (

https://www.facebook.com/pages/category/Charity-Organization/FreeShop-KDW-106154917438883/), Dzielna 7 Kielce (

https://pl-pl.facebook.com/dzielna7/) (accessed on 24 February 2022)). It was born out of the concept of donation boxes located in various districts of Poznań, in which local residents could leave unsuitable or useless things to make them available to others. Presently, Podzielnia is not only a place where things are exchanged, but a space for sharing ideas about the circular economy and climate change as well. The essential objective of freeshops is to prevent excessive consumption and waste. Poland is in 41st place on the Climate Risk Index, which means that the country is rather sensitive to climate changes. Adverse weather conditions can occur over time, which means that any activity that lowers the risk of them should be appreciated. One solution to support slowing climate change is to reduce consumption.

The main purpose of this paper is to describe the role of freeshops in the circular economy and to find factors that can support the development of this idea and contribute to its expansion. In this paper, two groups of factors were identified: economic and conservation. Moreover, this article presents the opinions of “Gen Z” individuals on the issue of freeshops, as one of the methods of implementing a circular economy model. There is some research about the X and Y generations available, and there is a gap to fill in the Z generation [

3].

This paper consists of the theoretical background (where economic concepts and other research are described), a materials and methods section (about methodology of research), results (conclusions for individual groups of students, depending on their attitude towards freeshop), discussion (where results are presented in comparison to other research), and the conclusions (with some recommendations for freeshops and the limitations of the survey).

In order to assess which of the identified factors most strongly influence the willingness to exchange goods instead of purchasing them, a survey was carried out among 381 students of the University of Gdańsk. The results were presented using the affinity analysis divided into three separate groups: people who would leave their useless things (1), take things they need (2), and both (3).

2. Theoretical Background

The beginnings of the circular economy (CE) can be found in the paper of The Club of Rome (the first one dated 1972), where limits of growth were defined [

4]. Nowadays, the popularity of the circular economy is growing [

5,

6,

7,

8]: it manifests itself in the fields of politics (on a supranational e.g., European Union [

9,

10] and national [

11] level), the work of non-governmental organizations (e.g., Ellen MacArthur Foundation), and in science.

In general, the CE integrates social, economic, and natural aspects of various management levels [

12,

13]:

- −

micro (e.g., creating eco-products, minimizing waste, introducing the system of environmental management) [

14];

- −

mezzo (e.g., creating industrial eco-parks) [

15]; and

- −

macro (e.g., creating eco-cities and eco-regions) [

16,

17,

18].

The idea of circularity is based on the 3R concept (reduce, reuse, recycle). An extension of this approach is the Canadian 4RV + OGE S concept (reduce, reuse, recycle, rejected + zero emission of greenhouse gases) and Swiss 5R (reduce, repair, reuse, recycle, rethink) [

13]. Finally, a notion was developed to “9 R”: refuse (treated as a 0-level), rethink, reduce, reuse, repair, refurbish, remanufacture, repurpose, recycle, and recover [

18]. In the “9 R”, idea refuse is the most desirable customer behavior, whilst reuse is connected with extending the lifespan of a product thanks to it being used by another consumer [

1]. It can be assumed that the circular economy can also be considered from the point of view of consumer behavior, thus there should be one more level: the consumer. This kind of approach can be found in some political regulations as “sustainable consumption” (e.g., in the Polish Circular Economy Road Map). A definition of sustainable consumption was proposed in 1994 at the Oslo Symposium: “the use of services and related products, which respond to basic needs and bring a better quality of life while minimizing the use of natural resources and toxic materials as well as the emissions of waste and pollutants over the life cycle of the service or product so as not to jeopardize the needs of further generations” [

19]. According to the European Commission, consumer choices may support or hinder the development of a circular economy [

10].

On the other hand, there is another concept connected with sustainable consumer behavior and close to the circular economy, called zero waste [

20,

21]. The Zero Waste International Alliance defined Zero Waste as “The conservation of all resources by means of responsible production, consumption, reuse, and recovery of products, packaging, and materials without burning and with no discharges to land, water, or air that threaten the environment or human health”. In turn, plenty of authors connected “zero waste” or “less waste” with a lifestyle. The basis of the concept of a freeshop is to reuse things that are useless for their owners. It promotes exchange in place of purchase, giving things back instead of throwing them away. Thus, it is strictly connected with “R” ideas and with zero waste consumers’ lifestyles.

Moreover, the life cycle of products affects the environment to a great degree, including due to the emission of greenhouse gases. Among the sectors with a major impact on the environment is the fashion industry [

22]. Some authors pointed out that the fashion industry is the world’s third biggest manufacturing industry behind the automotive and technology industries [

23]. The next problem defined by the authors is that the phenomenon of fast-fashion, which involves quickly rotating clothes collections to be current with the trends in the industry, has a particularly negative impact on the environment. The continuous availability of new collections has contributed to about 50% growth in clothes production [

24]. The authors found that only 1% of the materials used in this sector are recycled, even though, according to some estimates, about 95% could be recycled [

24,

25]. One of the methods of solving the above-mentioned problems is second-hand stores, which have attracted the interest of researchers for some time [

26,

27] and generate considerable interest among representatives of the X generation [

28,

29,

30]. A relatively new form of exchanging various products, but mostly clothes, are freeshops. They are not a frequent object of studies. One example of detailed analysis is the paper by Nord, which indicates that, among other things, a mean of 10 tons of CO

2 per freeshop per year can be avoided when reusing things from a freeshop instead of buying new products [

31]. Moreover, one element of the research indicated that the active use of clothes for an additional 9 months resulted in a 20–30% reduction of waste and CO

2 emission per piece [

32]. By avoiding the consumption of new products, fewer virgin resources are needed for production and less waste will be produced, leading to less emissions created. In the field of carbon neutrality, there is a possibility to offset carbon footprint by individuals, especially connected with travel. The authors [

33] discovered the effect of global warming, environmental awareness, participation of others and social norms. On the other hand, some authors [

34] stressed that buying carbon credits is not enough because there is the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, not offset them. According to this point of view, the freeshop fulfils its proper role.

The freeshops concept is able to support the reuse idea, reduce CO

2 emission and amount of waste, and—finally—reduce the profitability of the fast fashion sector. However, there is a need to increase its popularity. A challenge revealed in the research on freeshops is the motivation of customers relating to the use of solutions of this type. The following papers may be referred to in this respect, among others: [

14,

35]. Results obtained do not indicate the motivations of clients explicitly; they include but are not limited to cost-saving aspects, customer awareness, a legal system in a given country and awareness campaigns [

35]. Moreover, marked differentiation may be found in the outcome achieved depending on the country the analysis concerns.

However, the above-mentioned research has not taken into account issues relating to previous experiences of using freeshops or being acquainted with the concept itself (how much it affects declarations of specific behavior and motivation of customers). We are trying to fill in this research gap with this study.

Based on other research [

14,

35], it was assumed that the motivation to go to a freeshop (to leave or take things or both) among the surveyed students is determined primarily by factors related to environmental climate changes and environmental protection (hypothesis 1). This hypothesis was connected not only to the theory, but also to the economic reality: omnipresent narrative related to climate change and anthropopressure. It is manifested in the marketing communication of enterprises (e.g., declaring the use of recycled plastic or green energy) in activities of miscellaneous types of NGOs (such as the Ellen MacArthur Foundation), as well as individual people (e.g., Greta Thunberg) and in various types of pro-ecological actions (e.g., WWF’s Earth Hour). Its impact in Poland is visible, among others, in climate protests of young people—Youth Climate Strike. Moreover, consumer awareness of the harm of over-consumption and faster circulation of things or planned obsolescence is gradually increasing. Freeshop focuses much of its attention on popularizing knowledge of circular economy and shaping pro-environmental attitudes [

28,

29,

30].

Freeshops are an example of gift economy, which means giving and receiving something that meets people’s needs—but it is still too little seen as ‘economy’ today. From an anthropological point of view, we know that in the past some cultures were based on a gift economy [

36]. According to the authors [

37,

38], sharing may be motivated by economic reasons: like utility maximizing behavior.

On this basis, it was assumed that the motivation to use the offer of a freeshop among the surveyed students is influenced by factors related to the management of one’s financial resources (hypothesis 2). In such a situation, a factor that may primarily affect an average student’s motivation is one’s limited budget. The Warsaw Institute of Banking and The Union of Polish Banks data showed that students’ nominal monthly expenses rose from 1574 PLN in 2016 to 1904 PLN in 2019, and they are still rapidly rising (to 3177 PLN in 2022) [

39]. Exchanging goods instead of buying them generates savings, which may, to some extent, offset the rising cost of living. From the point of view of the freeshop idea, this is a less positive motivation. However, it has the advantage of being able to create environmental awareness among those driven by the budget factor.

3. Materials and Methods

The study was carried out in May 2019 among 381 students of full-time and extramural studies at the University of Gdansk Faculty of Economics (202 female and 170 male students; 9 persons did not indicate their gender). The average age of respondents was 20.8. Out of the respondents, 70 persons (18%) had encountered the concept of a freeshop, while 307 persons (81%) did not know it before. Only 33 respondents (9%) declared that such a solution does not suit them. On the other hand, 133 interviewees (35%) would donate their things to a freeshop, 25 (7%) would use it by taking things home, while the largest group of 169 students (44%) would do both: give and take things.

The sample selection was deliberate. An earlier study indicated differences in the perception of the use of second-hand things in different age groups in Poland. The alleged cause of it was the socio-economic situation in which individual generations grew up and functioned. The special impact was based on the shortage of goods that existed from approximately World War II until the late 1980s. These circumstances caused older Polish people to show less interest in second-hand items than younger generations [

40,

41]. Furthermore, the fashion sector, in particular fast fashion, is strongly connected with young people, who constitute a high percentage of its customers. Although recent research indicates that in the group of young customers (students) there is a growing awareness of the negative phenomena related to impulse purchases of new clothes, this group of youth and young adults still remains the main customer segment [

42]. Therefore, it was decided to conduct a survey among young people who have some knowledge about the functioning of the economy. In addition, as freeshops are a new trend, it has not been studied in literature to a sufficient degree how customers perceive this segment and what influences their decisions to use such services. On the other hand, some research indicated that there were complex relationships between personal background, academic and cognitive variables, and environmentally supportive behavior. The authors indicated that environmental lectures influenced cognitive and behavioral environmental concerns, so there is a need to have universities create a formal teaching plan related to environmental knowledge, awareness, and critical thinking skills to promote environmental awareness and address unsustainable lifestyles and attitudes [

43]. This article is aimed at filling this gap and presenting results of research carried out on a sample of young people, who are potentially most interested in this model of shopping, especially in Polish circumstances.

The survey consisted of 5 parts that concerned: A—knowledge of a freeshop concept, B—a visit to a freeshop (only for persons who were familiar with the concept of a freeshop), C—an attitude to consumption (an assessment of 6 statements in the 5-degree Likert scale where 5 meant surely yes, whilst 1—surely no), D—an attitude toward actions related to a circular economy/zero waste and money saving (an assessment of 15 statements in the 5-degree Likert scale (where 5 meant definitely important, whilst 1—totally irrelevant), and M—a matrix (sex, age, an attitude to using freeshops). The list of statements we based on the literature review [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49] and circular economy goals defined in governmental and non-governmental documents [

9,

10,

11]. We proposed our own set of factors that we thought best reflected the freeshop idea. In the “attitude to consumption” part, we have singled out such variables as shown in

Table 1.

The second part was about pro-ecological behaviour defined in the literature. We distinguished 15 variables, which might be connected with the freeshop concept (

Table 2).

Sets of variables (C1, C2, …, C6 or D1, D2, …, D15) were essential for the study. Each of them represented a single statement from the survey and could assume exactly one mark on a scale from 1 to 5. The first step was to find out which statements were crucial to respondents and how they assessed them. It was measured with medians. The number of answers was convergent with medians: as a rule, there were the most indications for the median values. The most important sentences with median marks were the basis for discovering the association rules among them. The first group was dedicated to finding out patterns in students’ segments in attitude to consumption, while the second was to investigate different behaviors, defined as ecological.

An affinity analysis was used to evaluate data and create profiles after division into 2 categories: (1) knowing the term freeshop before or not knowing the term and (2) donating things, taking things, or both. Researched association rules were divided into an attitude to consumption and in environment-positive behavior among each group. An association rule in an affinity analysis was defined as the ordered pair (e.g., C1, C2) of statements. This relation was described as: C1 ⇒ C2 (provided that sub-transactions did not contain mutual variables (V(C1)∩V(C2) = ∅) and were disjoint/exclusive (C1∩C2 = ∅)). Statement C1 of rule C1 ⇒ C2 was called the antecedent, while statement C2—the consequent [

44]. Two indicators of affinity analysis were used. One of them was support (understood as the percentage of answers that support the rule C1 ⇒ C2 among the total of students’ answers. It takes values from 0 to 1. The higher was the value of the support, the more frequently a rule appeared in students’ answers. We adopted the value 0.25 as the borderline for analyzing students’ responses. The second was confidence defined as the percentage of transactions which support the rule C1 ⇒ C2 among all transactions supporting C1. In other words, it was a conditional probability of the occurrence of C2, if C1 happened. Confidence shows the strength of an association rule and measures it from 0 to 1.

The first division was made to check if there were any differences in researched issues between people who heard about freeshops and those who did not. This part included the answers of 377 respondents whose questionnaires were completed in the studied scope (answers to the closed question and full assessment on the Likert scale). It was directly connected to the purpose of the paper. Secondly—in relation to the hypothesis—data were divided into 3 clusters connected with using freeshop. A total of 327 respondents declared their willingness to use freeshop in one of the three ranges and their answers were the subject of another analysis. Answers of students who definitely did not want to visit freeshop were not taken into account. Our target was to find out what kind of factors may positively influence youths who consider a freeshop as a solution for them. However, the potential of convincing people who do not appreciate such an idea may be interesting for further research.

4. Results

All respondents gave the highest scores (median 5) to two statements, namely that: people currently have too many things they do not use and that reusing and sharing things will enable one to save money. The lowest score (median 3) was given to the statement that reusing and sharing things is necessary for environmental reasons. Therefore, one could conclude that students do not perceive any aspects related to environmental protection in the freeshop concept.

When examining attitudes related to the circular economy and zero waste, for all questioned students, the following was very important (median 5): waste segregation, recycling, energy savings, using renewable energy sources, plastic elimination (e.g., replacing it with other materials), the replacement of disposable products with multi-use products (e.g., bags, straws, cotton pads), adapting packaging to products (e.g., a size adequate to content, no redundant elements such as extra foil) and the full use of purchased food products. The least important (median 3) turned out to be the purchase of food products from certified ecological farms. It was connected directly to money saving because such products are more expensive.

After the division into groups of those who were familiar with the concept of a freeshop (hereinafter referred to as the “knowing”) and those who had not encountered that solution (hereinafter referred to as the “unknowing”), a basic difference occurred in the assessment of the declaration that “environmental problems result from, among other things, excessive consumption”. In the “knowing” group, the median of scores (in the scale from 1—definitely not, to 5—definitely yes) for this response was 4.5, while in the “unknowing” group it was at 3. In the area of CE and zero waste, differences occurred in the following statements (on a scale from 1—completely unimportant to 5—very important): energy saving (“knowing”—4.5; “unknowing”—5), plastic elimination (“knowing”—4, “unknowing”—5), and buying food products from certified ecological farms (“knowing”—3.5, “unknowing”—5).

4.1. Persons Familiar with the Concept of a Freeshop

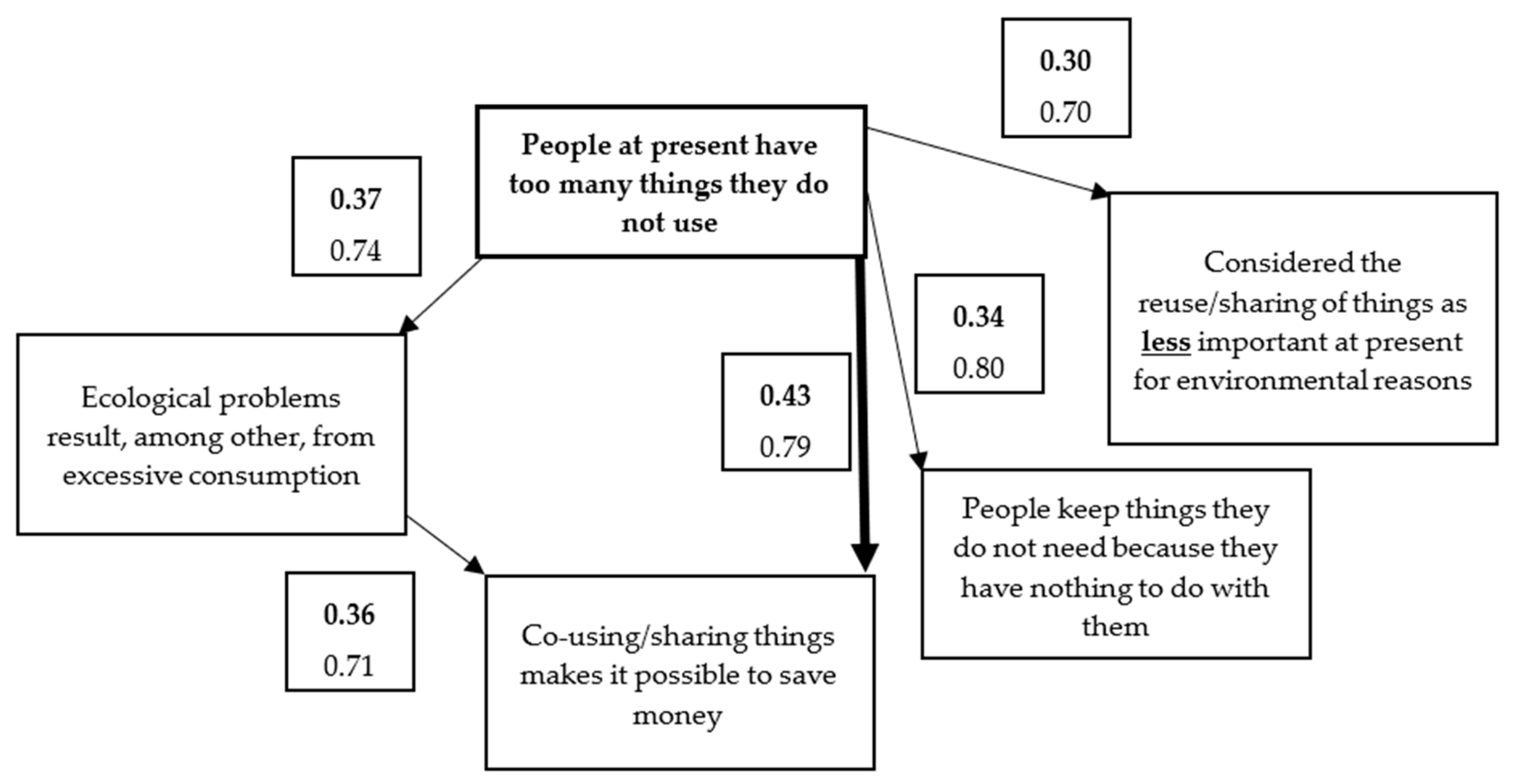

For persons who knew the concept of a freeshop, the most important factor in the area of consumption patterns was the excessive number of possessed and simultaneously unused things. If a knowing person agrees that presently people possess too many things they do not use (median: 5), he/she also thought that people keep unnecessary things because they have nothing to do with them (4). Moreover, if a knowing person strongly believed that at present people have too many things they do not use (5), he/she also thought that ecological problems result from excessive consumption (4.5). At the same time, it is surprising that, even if a knowing person was positive that nowadays people possess too many things they do not use (5), he/she considered it less important to co-use/share as necessary for ecological reasons (3). Simultaneously, if a knowing person was certain that, at present, people possess too many things they do not use (5) or that environmental problems result from excessive consumption (4.5), he/she also strongly believed that co-using/sharing of things makes it possible to save money (5).

The indicted declarations have been presented in the following diagram (

Figure 1) with values of support and confidence.

Respondents were also asked to rate statements related to CE and zero waste lifestyle. Thus, if a “knowing” person considered a use of multi-use products to be very important (median 5), he/she also considered as very important recycling (5) (support: 0.41, confidence: 0.74), the use of renewable energy sources (0.46, 0.82), and the adaptation of packaging to a product (0.41, 0.73). Moreover, if a “knowing” person considered the adaptation of packaging to a product as very important (5), he/she also considered as very important recycling (5) (support: 0.46, confidence: 0.76) and the use of renewable energy sources (5) (0.44, 0.74). Furthermore, if a “knowing” person considered the saving of energy as very important (5), he/she also considered as very important the use of renewable energy sources (5) (support: 0.40, confidence: 0.85) and recycling (5) (0.51, 0.84) and if a “knowing” person considered the use of renewable energy sources as very important (5), he/she also considered recycling to be very important (5) (0.51, 0.82).

Summarizing: even if the “knowing” equated overconsumption with environmental problems, the main reason for using a freeshop was still savings. They found important such environmentally-friendly behavior as using multi-use products, recycling, matching the packaging to the quantity of the product in it, using less energy, and from responsible sources. The “knowing” see that ecological problems have their source in excessive consumption; however, reusing or sharing things is only equated to savings. According to them, people do not have any idea what to do with useless things in a good state, so they keep them.

4.2. Persons Not Familiar with the Concept of a Freeshop

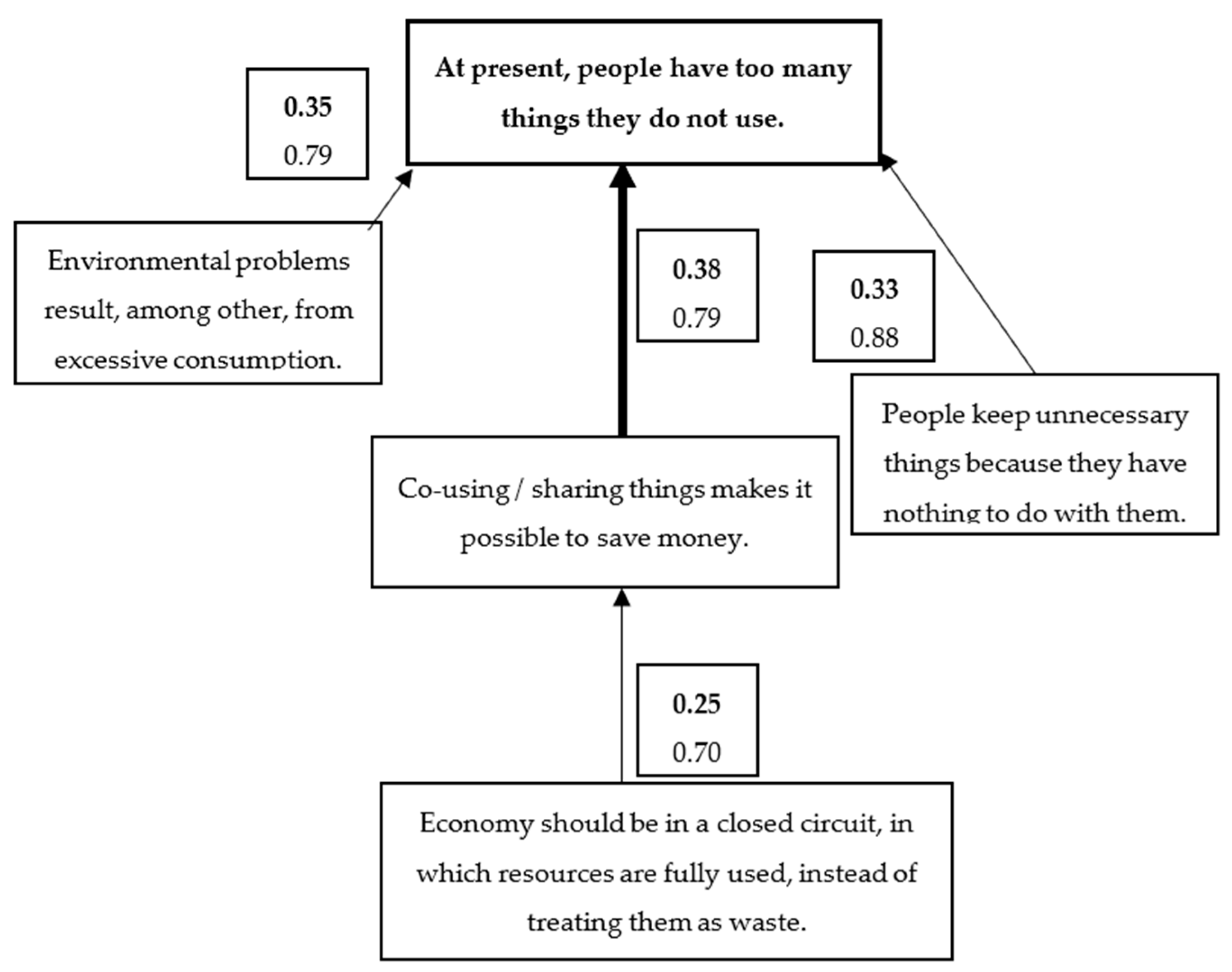

Respondents who had not used a freeshop before were positive that people presently possess too many things they do not use (median: 5), and also that people keep unnecessary things because they have nothing to do with them (4). They also strongly believed that ecological problems resulted from, among other things, excessive consumption (5) and that co-using things enables one to save money (5).

In other words, if an “unknowing” person was positive that reusing things enables one to save money (5), he/she also thought that people at present have too many things they do not use (5). Furthermore, if he/she thought that people keep unnecessary things because they have nothing to do with them (4), he/she also strongly believed that people at present possess too many things they do not use (5). If an unknowing person was of an opinion that environmental problems result from, among other things, excessive consumption (4), he/she also strongly believed that people at present possess too many things they do not use (5) and that reusing or sharing things makes it possible to save money (5).

The above-mentioned statements have been presented in the following diagram (

Figure 2) together with support and trust values.

If an “unknowing” person considered waste segregation as very important (median 5), he/she also considered as very important its recycling (5) (support: 0.55, confidence: 0.95), energy saving (5) (0.46, 0.80), using renewable energy sources (5) (0.78, 0.58) and the usage of multi-use products (5) (0.55, 0.76). Besides that, if a respondent considered plastic elimination as very important (5), he/she also considered its recycling as very important (5) (0.45, 0.83). If one considered adapting packaging to a product as very important (5), he/she also considered recycling to be very important (5) (0.49, 0.85). On the other hand, if an “unknowing” person considered the full use of purchased food products as very important (5), he/she considered recycling as very important as well (5) (0.44, 0.80). Considering energy matters: if a respondent thought that energy saving is very important (5), he/she also valued recycling (5) (0.53, 0.90) and the use of renewable energy sources (5) (0.51, 0.87). On the other hand, if one presumed that the use of renewable energy sources was very important (5), he/she also rated as very important recycling (5) (0.49, 0.85), the exchange of disposable products with multi-use ones (5) (0.46, 0.80) and the adaptation of packaging to a product (5) (0.46, 0.78). If an “unknowing” person considered the adaptation of packaging to a product as very important (5), he/she also considered as very important the exchange of disposable products with multi-use ones (5) (0.47, 0.81).

Summarizing: results in the “unknowing” group in its essence were similar to the “knowing” group. The “unknowing” noticed overconsumption as a problem, perceived its influence on the environment, but this was still not an overriding argument for reusing things. A primary reason for going to a freeshop was saving money. Considering CE behavior, it was visible that for these respondents recycling was highly important. However, in CE models, such as 9R, recycling is in a far position, mainly because of material deterioration (in many cases). According to the “unknowing”, people do not know what to do with useless things, so they keep them.

4.3. Persons Who Would Donate Things to a Freeshop

A large group of respondents (133 persons) would be ready to give away useless things to a freeshop. Out of such respondents, 19% were familiar with the concept of a freeshop and 10 persons had used such a solution (including nine who had donated things and one who had taken things from a freeshop). In total, 60% of the respondents in this category were female. Such persons were not ready to take anything from a freeshop with them.

In this group, if one was positive that the economy should be circular and resources should be fully used instead of treating them as waste (5), he/she also strongly believed that reusing/sharing things enables one to save money (5). If a donating person was convinced that reusing/sharing things makes it possible to save money (5), he/she was also certain that at present people have too many things they do not use (5). Moreover, if a giving person believed strongly that people keep too many things because they do not know what to do with them (5), he/she was also positive that presently people have too many things they do not use (5). Likewise, if a “giving” person was certain that environmental problems result from excessive consumption (5), he/she also believed strongly that nowadays people have too many things they do not use (5) (results are shown at

Figure 3).

Considering CE behavior, if a “giving” person treated waste segregation as very important (median 5), he/she also valued recycling (5) (support: 0.77, confidence: 0.96) and the adaptation of packaging to a product (0.48, 0.82). In terms of energy, if one thought that renewable energy sources are very important (5), he/she also thought that recycling is very important (5) (0.57, 0.82); in addition, when one noticed that energy saving is very important (5), he/she also evaluated as very important: renewable energy sources (5) (0.90, 0.76), the adaptation of packaging to a product (0.46, 0.77), and recycling (0.54, 0.91). If a “giving” person considered that suitable packaging of the product is very important (5), he/she also thought that renewable energy sources (5) (0.52, 0.79) and recycling (0.53, 0.82) are very important. In addition, if a “giving” person considered plastic elimination as very significant (5), he/she regarded that the usage of multi-use things (5) (0.45, 0.77), recycling (0.48, 0.82) and renewable energy sources (5) (0.46, 0.78) are significant as well. Taking into account products: if a “giving” person rated the usage of multi-use ones as very important (5), he/she also valued the adaptation of packaging to a product (0.49, 0.82), renewable energy sources (5) (0.51, 0.86) and recycling (0.49, 0.82). Moreover, if one appraised the full use of purchased food products as very important (5), he/she also valued the adaptation of packaging to a product (0.44, 0.77) and renewable energy sources (0.46, 0.81).

Summarizing: After distinguishing this group, it was possible to notice that the circular economy appeared in the affinity analysis. Thus, even if a giving person appreciated the idea of CE or zero waste, he/she still emphasized that reusing/sharing things enables one to save money. In this group of respondents, dependency was observed between product features (consumption of all content, multi-use) and renewable energy sources. Still, recycling turns out to be an important matter.

4.4. Persons Who Would Take Things

Only 25 out of all respondents would decide to only take things from a freeshop. In this group, 3 persons had met this solution in Poland before and had used it by donating things. In total, 64% of respondents in this group were male. Due to the small size of the sample, no further conclusions about this group were drawn.

4.5. Persons Who Would Donate Things to or Take Things from a Freeshop

The largest group of respondents, i.e., 169 persons, would decide both: to leave useless things and take things they needed. Out of them, 20% were familiar with the concept of a freeshop, and 16 had used that solution (8 persons had given things, 2—taken, and 6—both). In total, 59% were female. In this group, the following dependencies could be observed: if a “giving and taking” person was positive that economy should be circular (5), he/she also believed strongly that at present people possess too many things they do not use (5). If one was convinced that reusing/sharing things makes it possible to save money (5), he/she was also certain that presently people have too many things they do not use (5). If a respondent believed strongly that people keep unnecessary things because they have nothing to do with them (5), he/she also thought that nowadays people have too many things they do not use (5) and that environmental problems result from, among other things, excessive consumption (5). If a “giving and taking” person was certain that environmental problems result from excessive consumption (5), he/she also believed that at present people have too many things they do not use (5) (results are shown at

Figure 4).

According to respondents in this group, if one considered waste segregation as very important (median 5), he/she also valued recycling (5) (support: 0.60, confidence: 0.94) and energy saving (5) (0.50, 0.77). Furthermore, if energy saving was very important for someone (5), he/she also believed that: recycling (5) (0.58, 0.91), waste segregation (5) (0.49, 0.77), renewable energy sources (0.50, 0.79), and the full use of purchased food products (5) are important (0.48, 0.75). If someone thought that plastic elimination is very important (5), he/she also considered as significant the usage of multi-use products (5) (0.49, 0.85), the full use of purchased food products (5) (0.49, 0.77), renewable energy sources (0.48, 0.83) and recycling (0.50, 0.86). If an unknowing person considered as very important the usage of multi-use products (5), he/she also appreciated the full use of purchased food products (5) (0.50, 0.79), the adaptation of packaging to a product (5) (0.51, 0.80), waste segregation (0.50, 0.80), recycling (0.55, 0.87), energy saving (0.49, 0.78) and renewable energy sources (0.50, 0.79). If an interviewee valued the adaptation of packaging to a product (5), he/she also perceived as very important the adaptation of packaging to a product (0.47, 0.74). If a student thought that the use of renewable energy sources is very important (5), he/she also recognized recycling as very important (5) (0.60, 0.83). Moreover, if one responded that the adaptation of packaging to a product as very important (5), he/she also stated that waste segregation (5) (0.45, 0.71), recycling (5) (0.53, 0.84), energy saving (5) (0.47, 0.75) and the use of renewable energy sources (0.50, 0.79) are significant as well. If an “unknowing” person considered as very important the full use of purchased food products (5), he/she also considered as very important waste segregation (5) (0.46, 0.76), recycling (5) (0.51, 0.80) and renewable energy sources (0.49, 0.77).

Summarizing: With such a division applied, it was possible to notice that the question of circular economy appeared in the affinity analysis once again. As in the previous group, even if a respondent appreciated the idea of CE or zero waste, he/she was still motivated by saving money. Respondents in that group believed that people have too many items and they keep useless things because they do not know what to do with them. They perceived overconsumption as causing environmental problems. On the other hand, taking into account CE matters, it appeared that plastic elimination is significant and respondents connected it with the usage of multi-use products, the full use of purchased food products, renewable energy sources and recycling.

5. Discussion

Both in the group familiar with the concept of a freeshop and among those who had never come across that term, the most important reason for reusing things was economy, i.e., saving money. Surprisingly, for respondents who knew the concept of a freeshop, environmental aspects proved less important. This is particularly interesting because the premise of a freeshop includes the ideas of zero waste and the circular economy, which are closely related to the lower pressure on the natural environment and are often associated with environmental movements. Hence, it would seem logical that, among persons who were familiar with solutions such as a freeshop, problems related to ecology would be more popular.

Research directly connected with freeshops is very limited—there is another paper connected with reducing CO

2 emission via using second-hand things from such places in Sweden. Nord [

31] found out that only 0.0025% useless (for their owners) things were offered to freeshops, so the capability of reducing pollution in this way is very limited. Our results showed that only 18% of surveyed students were aware of such a solution, so on this point we agree with the idea of limited impact. On the other hand, there is a huge chance to popularize the freeshop idea. Most students interviewed connected with the concept of freeshops and were willing to leave unnecessary things and/or bring others with them. For the respondents, the economic factor turned out to be the most important, so developing freeshop projects should emphasize savings as a benefit. Ecological factors should be pointed out in second place, although they seem to be more important for people involved in developing such projects as a freeshop. Moreover, a relationship between fashion and freeshop activity can be observed. Most of the items left in freeshops are clothes. Some research indicates that generation Z may be more interested in second-hand clothes and more open to such solutions as a freeshop. It is visible especially in Poland where older generations using second-hand things reminds times of commodities shortages. In our research, we found that young Polish people, with basic economic knowledge, were willing to share unnecessary and needless things with others. Most of them did not have anything against using second-hand things. Unfortunately, it struck us that, even though there is a lot of research indicating the negative influence of overproduction and overconsumption on the environment, the main reason for sharing things according to the respondents, our students, was to save money. Our results corresponded to the observations in the other paper [

50] that, although there was a growing awareness of negative side of new clothing purchases among the group of young customers, they are still a very attractive group for fast fashion companies. Even though there is visible pro-ecological movement among Polish generation Z, the economic factor is still much more important for them. Moreover, other research about zero-waste conducted among University of Gdańsk students showed that for all respondents the economical factor was more important, while the environmental factor was in second place [

50]. This was confirmed in our study. Simultaneously, there is a possibility to treat a savings factor as a chance to develop the freeshop idea. Results of the survey conducted by The Warsaw Institute of Banking and The Union of Polish Banks indicated that the cost of studying in Poland is still growing. Money pressure may be a dimension of the attitude change.

Summarizing, of the two hypotheses, the saving of money factor as the most important turned out to be true for surveyed students’ group. Unfortunately, although students had basic economics knowledge, they appreciated conservation problems (hypothesis 1) less than savings. The solution proposed by other authors is to supplement the teaching plans with environmental aspects, as this increases awareness. This could be a layout changing solution.

6. Conclusions

Places such as freeshops seem to be needed: students associated the opinion that people possessed too many things with the problem that they did not know what to do with them. It gives a lot of space to develop ideas connected with exchanging and sharing goods. Two types of implications of the survey results can be identified. The first relates to the freeshop operators and concerns the customer communication model. The second relates to the scope for further research and development of the concept from a theoretical perspective. The freeshop is a relatively new concept and not embedded in the literature, hence addressing this topic seems promising.

As mentioned above, there are several pieces of advice that can be given to freeshops. First of all, there is a need to communicate that there are places where one can easily bring unwanted things. It is the chance to “release” additional resources, which can be reused. Thus, it can be a way to increase the replacement of purchases and, consequently, reduce overconsumption. Secondly, although such places are highly dedicated to environmental/CE/zero waste matters, for the majority of people, the most important is a money saving factor, even though they see that overconsumption and waste are a problem. Therefore, if such places want to encourage people to reuse things, they should use “money arguments” in their communication. Typically, changes in consumption habits are motivated on an individual scale by economic benefits. This should be taken into account when designing sustainable consumption solutions, even though for the institutions running them, zero waste and CE values are more important. Educational activities of freeshops may be connected with CE hierarchy (e.g., Potting’s et al. 9R model), where reusing (as well as rethinking or refusing) are more desirable than recycling. The educational role of freeshop is highly desirable, as environmental awareness also affects other aspects, such as individual and voluntary carbon offsets [

51,

52]. In other words, it will be easier to develop and spread the idea of freeshop based on communication related to managing one’s own budget than on the idea of sustainability. At the same time, an element of education and promotion of sustainability is essential to create environmental awareness and permanently affect a change in attitudes.

Due to high interest among respondents, it may prove interesting to implement such solutions at locations available to students. The most intuitive site seems to be dormitories. In addition to the function of exchanging goods, it can be an interesting meeting place for the academic community. Educational projects related to human impact on the environment can be carried out there—aimed not only at students and university employees, but also the local community. Another aspect that appears in the case of such a project is the way of managing such units, in which students may be involved.

In the context of other authors’ research, it seems extremely important to prevent fast fashion. Donating clothes in good condition and having them used by others can have a positive impact on the issue so defined. In particular, environmental education, which is also partly carried out by freeshops, can be important in this area.

Another challenge to which freeshop responds is the reduction of the carbon footprint. The authors argue whether individual carbon offsetting is a good solution. Some argue that it gives a false sense of ‘washing away the guilt’ [

53]. As Nord has shown, freeshops enable effective and calculable carbon reductions [

31].

The authors defined environmental responsibility as a part of a broad philosophy of the functioning of the modern economy (like sustainable development and zero waste behavior) [

54]. The freeshop idea has a direct impact on shaping ethical attitudes in the area of environmental protection.

The freeshop’s activities are part of scientific research related to broader changes in consumption, environmental protection, greenhouse gas emissions, the zero-waste movement and circular economy. Additionally, elements of behavioral economics can also be used in further research, including conducting an experiment by opening a freeshop in a dormitory and observing the development of the phenomenon: barriers and supporting factors. An interesting course of further research may involve comparative studies on an international scale, which would enable one to compare motivations and decision-making by persons in different countries. It might also be interesting to reach a more diverse group of respondents.

The study had a few limitations. The survey was primarily distributed to students. Therefore, a generalization of the findings to other age groups might be limited. Another limitation of the research—or in fact rather of the whole operating model—is the question of financing this mode of activity and distribution of clothes and other products. However, this problem may be an object of analysis in another study.