Industrial Poverty Alleviation, Digital Innovation and Regional Economically Sustainable Growth: Empirical Evidence Based on Local State-Owned Enterprises in China

Abstract

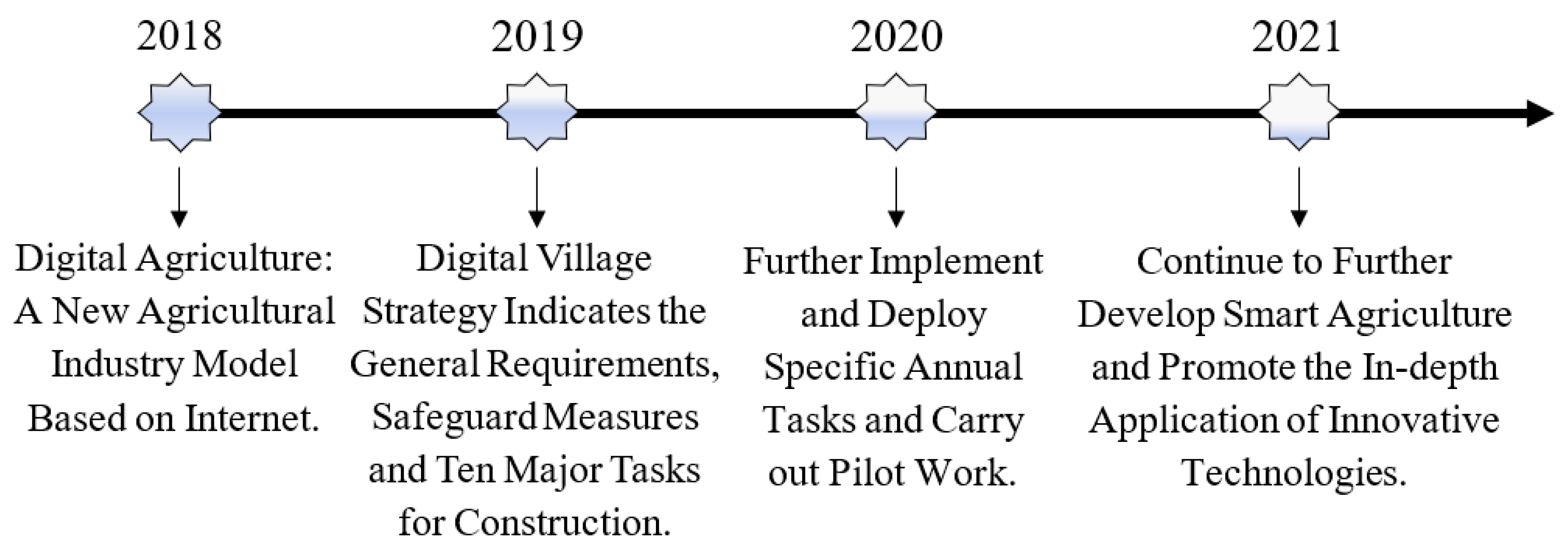

1. Introduction

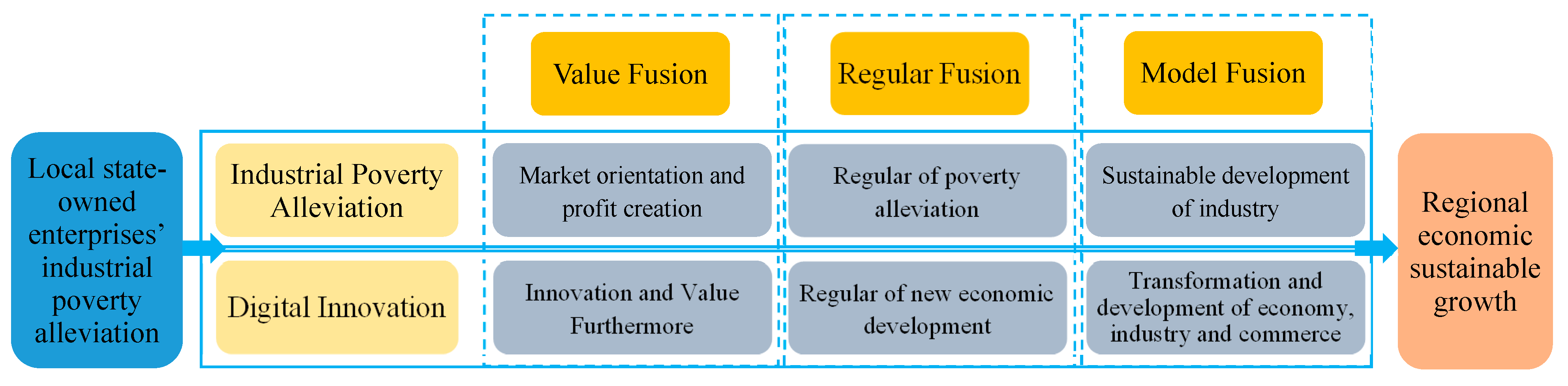

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Industrial Poverty Alleviation and Regional Economic Sustainable Growth

2.2. Industrial Poverty Alleviation, Digital Innovation and Regional Economically Sustainable Growth

3. Study Design

3.1. Variable Design

3.1.1. Dependent Variable: Regional Economic Sustainable Growth

3.1.2. Independent Variable: Industrial Poverty Alleviation

3.1.3. Intervening Variable: Digital Innovation

3.1.4. Controlled Variables

3.2. Empirical Model Design

3.2.1. Benchmark Regression Test Model Design

3.2.2. Endogeneity Test Model Design

3.2.3. Intermediary Effect Test Model Design

3.3. Data Selection and Description

4. Results and Analysis of Empirical Tests

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Results and Analysis

4.2. Correlation Test Results and Analysis

4.3. Empirical Results and Analysis

4.3.1. Benchmark Regression Test Results

4.3.2. Endogeneity Test Results

4.3.3. Intermediary Effect Test Results

4.4. Heterogeneity Grouping Regression Test Results and Analysis

4.4.1. Grouping Test between Agriculture-Related Enterprises and Non-Agriculture-Related Enterprises

4.4.2. Grouping Test between High-Tech Enterprises and Non-High-Tech Enterprises

4.4.3. Grouping Test between Follow-Up Poverty Alleviation Plan Enterprises and No-Follow-Up Poverty Alleviation Plan Enterprises

5. Conclusions

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, L.; Xu, M. Research on Poverty Reduction Effect of China’s Precision Poverty Alleviation Policy: Empirical Evidence from Quasi-natural Experiment. Stat. Res. 2019, 36, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Yan, H.; Huang, X.; Wen, H.; Chen, Y. The Impact of Foreign Trade and Urbanization on Poverty Reduction: Empirical Evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 735620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Ping, W.; Shan, Q.; Wang, J. Summary from China’s Poverty Alleviation Experience: Can Poverty Alleviation Policies Achieve Effective Income Increase. J. Manag. World 2022, 38, 70–83. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Ravallion, M. The Developing World Is Poorer than We Thought, but No Less Successful in the Fight Against Poverty. Q. J. Econ. 2010, 125, 1577–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, L. Evaluation of China’s Targeted Poverty Alleviation Policies: A Decomposition Analysis Based on the Poverty Reduction Effects. Sustainability 2021, 13, 662543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, J. China’s Poverty Reduction through Industrial Development: Progress and Prospects. Contemp. Econ. Manag. 2020, 42, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, M.H.; Santos, S.C.; Neumeyer, X. Entrepreneurship as a Solution to Poverty in Developed Economies. Bus. Horiz. 2020, 63, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Yang, H.; Liao, F. Determinants of the Disclosure Tone of Poverty Alleviation Information: The Case of A-share Listed Companies in China’s Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchange. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2022, 29, 988–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, G.E.; Lόpez, J.H.; Maloney, W.F.; Arias, O.; Luis Servén, L. Poverty Reduction and Growth: Virtuous and Vicious Circles; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Thorbecke, E. Multidimensional poverty: Conceptual and measurement issues. In The Many Dimensions of Poverty; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Thorbecke, E. The interrelationship linking growth, inequality and poverty in sub-Saharan Africa. J. Afr. Econ. 2013, 22 (Suppl. 1), i15–i48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravallion, M. Why don’t we see poverty convergence? Am. Econ. Rev. 2012, 102, 504–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrero, G.A.; Servén, L. Growth, Inequality, and Poverty: A Robust Relationship? Policy Research Working Paper (WPS); The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, Y.; Shimeles, A.; Thorbecke, E. Revisiting cross-country poverty convergence in the developing world with a special focus on Sub-Saharan Africa. World Dev. 2019, 117, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorbecke, E.; Ouyang, Y. Towards A Virtuous Spiral Between Poverty Reduction And Growth: Comparing Sub Saharan Africa With The Developing World. World Dev. 2022, 152, 105776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, K.; Feng, Q.; Ganeshan, R.; Sanders, N.R.; Shanthikumar, J.G. Introduction to the Special Issue on Perspectives on Big Data. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2018, 27, 1639–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, A.; Tucker, C. Digital Economics. J. Econ. Lit. 2019, 57, 3–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. The Endogenous Attributes and Industrial Organization of Digital Economy. J. Manag. World 2022, 38, 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, B.; Qu, A.; Li, A.; Chen, X. Research on Construction Methods of Digital Village. Hubei Agric. Sci. 2022, 61, 183–187. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.; Xie, T. On the Effective Linkage Mechanism and Effect Between Industrial Poverty Alleviation and Industrial Revitalization from the Perspective of Digital Economy. J. Guangdong Univ. Financ. Econ. 2022, 37, 30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Torky, M.; Hassanein, A.E. Integrating Blockchain and the Internet of Things in Precision Agriculture: Analysis, Opportunities, and Challenges. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 178, 105476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tulder, R. The Role of Business in Poverty Reduction towards a Sustainable Corporate Story? United Nations Research Institute for Social Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- De Backer, K.; Miroudot, S.; Rigo, D. Multinational Enterprises in the Global economy: Heavily Discussed, Hardly Measured. 2019. Available online: www.oecd.org/industry/ind/MNEs-in-the-global-economy-policy-note.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Castillo, O.N.; Chiatchoua, C. US multinational enterprises: Effects on poverty in developing countries. Res. Glob. 2022, 5, 100090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q. Discussion on the Effective Connection Between Poverty Alleviation and Rural Revitalization: Based on the Perspective of Policy Transfer and Continuity. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 20, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, S. The Organic Integration of Poverty Alleviation and Rural Revitalization Strategies: Goal Orientation, Key Areas and Measures. Chin. Rural Econ. 2020, 36, 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Cao, J. The Mechanism of the Industrialization of Precise Poverty Alleviation. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2017, 27, 127–135. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, G.; Hu, X.; Liu, W. China’s poverty reduction miracle and relative poverty: Focusing on the roles of growth and inequality. China Econ. Rev. 2021, 68, 101643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanic, M.; Martin, W. Sectoral Productivity Growth and Poverty Reduction: National and Global Impacts. World Dev. 2018, 209, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yang, Y.; Gu, J. Can Resident Village Assistance of the First Secretary Enhance the Social Capital in Village: A Field Experiment Study. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 47, 110–124. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, F. China’s Poverty Alleviation ‘Miracle’ from the Perspective of the Structural Transformation of the Urban–rural Dual Economy. China Political Econ. 2021, 4, 86–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Yu, Z.; Wei, Y.D.; Wang, M. Internet Access, Spillover and Regional Development in China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 9060946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostmeier, E.; Strobel, M. Building Skills in the Context of Digital Transformation: How Industry Digital Maturity Drives Proactive Skill Development. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 718–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Lou, J. The Impact and Spillover Effect of Digital Transformation on Enterprise Upgrading. J. Zhongnan Univ. Econ. Law 2022, 66, 119–133. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Huang, Z. Digital Economy and High-quality Development: Mechanisms and Evidence. China Econ. Q. 2022, 22, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C.I.; Tonetti., C. Nonrivalry and Economics of Data. Am. Econ. Rev. 2020, 110, 2819–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, T.F. Leisure Agriculture in the Era of Targeted Poverty Alleviation. Asian J. Educ. Soc. Stud. 2020, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, P.; Zhou, Z.; Kim, D.J. A New Path of Sustainable Development in Traditional Agricultural Areas from the Perspective of Open Innovation: A Coupling and Coordination Study on the Agricultural Industry and the Tourism Industry. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Li, Y.; Ren, S.; Wu, H.; Hao, Y. The role of digitalization on green economic growth: Does industrial structure optimization and green innovation matter? J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Song, J.; Lee, C.-C. Can digital finance narrow the regional disparities in the quality of economic growth? Evidence from China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 76, 502–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Rivera, J.; García-Mora, F. Internet access and poverty reduction: Evidence from rural and urban Mexico. Telecommun. Policy 2021, 45, 102076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Chen, S.; Li, C. Financial technology as a driver of poverty alleviation in China: Evidence from an innovative regression approach. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, X.; Gong, J.; Xu, J. Technology empowerment: A path to poverty alleviation for Chinese women from the perspective of development communication. Telecommun. Policy 2022, 46, 102328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, H.; Burgess, G. Digital exclusion and poverty in the UK: How structural inequality shapes experiences of getting online. Digit. Geogr. Soc. 2022, 3, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechman, E.; Popowska, M. Harnessing digital technologies for poverty reduction. Evidence for low-income and lower-middle income countries. Telecommun. Policy 2022, 46, 102313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. The Digital Transformation of Business Models in the Creative Industries: A Holistic Framework and Emerging Trends. Technovation 2020, 92, 102012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Xie, H.; Meng, X.; Zhang, Q. Digital Transformation and Enterprise Value: Empirical Evidence based on Text Analysis Methods. Economist 2021, 33, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, F.; Lin, C.; Zhai, H. Digital Transformation, Corporate Innovation, and International Strategy: Empirical Evidence from Listed Companies in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Cai, G.; Liu, J. Research on Classified Governance of State-owned Listed Companies in China. J. Sun Yat-Sen Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 57, 175–192. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.; Xiao, S.F.; Li, X.J.; Li, W.W. Non-executive Employee Equity Incentive and Innovation Outputs: Empirical Evidence from High-tech Listed Companies in China. Account. Res. 2019, 40, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Mean | Median | Standard Deviation | Maximum | Minimum | 5% | 25% | 75% | 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RESG | 0.063 | 0.068 | 0.022 | 0.118 | −0.231 | 0.019 | 0.050 | 0.078 | 0.088 |

| WIPA | 0.269 | 0.000 | 0.444 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| DIPA | 3.006 | 0.000 | 5.589 | 20.832 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 14.235 |

| WDI | 0.701 | 1.000 | 0.458 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| DDI | 1.316 | 1.099 | 1.197 | 5.684 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 2.079 | 3.611 |

| Size | 22.987 | 22.896 | 1.330 | 28.636 | 17.954 | 20.991 | 22.056 | 23.801 | 25.297 |

| Debt | 0.496 | 0.501 | 0.207 | 2.123 | 0.027 | 0.163 | 0.336 | 0.646 | 0.832 |

| Roa | 0.048 | 0.046 | 0.076 | 0.745 | −1.495 | −0.027 | 0.027 | 0.070 | 0.139 |

| Growth | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.083 | 4.290 | −0.010 | −0.004 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.006 |

| H10 | 0.185 | 0.153 | 0.130 | 0.753 | 0.000 | 0.035 | 0.086 | 0.261 | 0.453 |

| MS | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.025 | 0.474 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.012 |

| Area | 0.173 | 0.000 | 0.378 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| IET | 7.473 | 7.047 | 1.790 | 11.109 | 0.969 | 4.557 | 6.393 | 9.054 | 10.290 |

| Variable | WIPA = 1 | WIPA = 0 | t Test | Wilcoxon Z | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | Median | N | Mean | Median | |||

| RESG | 790 | 0.066 | 0.070 | 2145 | 0.061 | 0.068 | 5.160 *** | 4.674 *** |

| Variable | RESG | WIPA | DIPA | WDI | DDI | Size | Debt | Roa | Growth | H10 | MS | Area | IET |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RESG | 1 | ||||||||||||

| WIPA | 0.095 *** | 1 | |||||||||||

| DIPA | 0.083 *** | 0.886 *** | 1 | ||||||||||

| WDI | 0.057 *** | 0.071 *** | 0.063 *** | 1 | |||||||||

| DDI | 0.052 *** | 0.035 ** | 0.019 *** | 0.718 *** | 1 | ||||||||

| Size | −0.017 | 0.172 *** | 0.169 *** | 0.148 *** | 0.140 *** | 1 | |||||||

| Debt | −0.012 | −0.012 | −0.007 | 0.029 * | −0.006 | 0.394 *** | 1 | ||||||

| Roa | −0.008 | 0.003 | −0.002 | 0.009 | 0.005 | 0.042 ** | −0.021 | 1 | |||||

| Growth | 0.016 | 0.023 | 0.028 | 0.010 | 0.027 | 0.021 | 0.023 | −0.003 | 1 | ||||

| H10 | −0.025 | 0.131 *** | 0.131 *** | 0.062 *** | 0.007 | 0.243 *** | −0.089 *** | 0.026 | 0.040 ** | 1 | |||

| MS | −0.037 ** | −0.073 *** | −0.062 *** | 0.011 | 0.057 *** | −0.098 *** | −0.066 *** | −0.010 | −0.005 | −0.110 *** | 1 | ||

| Area | 0.081 *** | 0.163 *** | 0.144 *** | 0.019 | −0.008 | −0.060 *** | 0.031 * | −0.010 | −0.004 | 0.006 | −0.052 *** | 1 | |

| IET | −0.008 | −0.176 *** | −0.168 *** | 0.039 ** | 0.065 *** | 0.014 | −0.056 *** | 0.019 | −0.007 | 0.005 | 0.023 | −0.433 *** | 1 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WIPA | 0.0048 *** (0.0009) | 0.0048 *** (0.0010) | ||

| DIPA | 0.0003 *** (0.0001) | 0.0003 *** (0.0001) | ||

| Size | −0.0003 | −0.0003 | ||

| Debt | −0.0011 | −0.0013 | ||

| Roa | −0.0022 | −0.0021 | ||

| Growth | 0.0045 | 0.0044 | ||

| H10 | −0.0067 ** | −0.0066 ** | ||

| MS | −0.0302 * | −0.0314 * | ||

| Area | 0.0049 *** | 0.0051 *** | ||

| IET | 0.0006 ** | 0.0005 ** | ||

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 0.0614 *** | 0.0617 *** | 0.0654 *** | 0.0648 *** |

| Adj R2 | 0.0087 | 0.0065 | 0.0153 | 0.013 |

| F-statistics | 26.6286 *** | 20.1893 *** | 60.7888 *** | 54.458 *** |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WIPA | 0.0055 *** (0.0018) | 0.0047 *** (0.0014) | ||||||

| DIPA | 0.0003 ** (0.0001) | 0.0002 ** (0.0001) | ||||||

| WIPA × WDI | 0.0076 *** (0.0021) | |||||||

| WIPA × DDI | 0.0011 *** (0.0001) | |||||||

| DIPA × WDI | 0.0075 *** (0.0001) | |||||||

| DIPA × DDI | 0.0071 *** (0.0006) | |||||||

| WDI | 0.0028 *** (0.0009) | 0.0029 *** (0.009) | 0.0029 *** (0.0010) | 0.0032 *** (0.0010) | ||||

| DDI | 0.0010 *** (0.003) | 0.0010 *** (0.003) | 0.0011 *** (0.0004) | 0.0012 *** (0.0004) | ||||

| Size | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | −0.0001 | −0.0001 | −0.0001 | −0.0001 | ||

| Debt | −0.0022 | −0.0025 | −0.0012 | −0.0015 | −0.0014 | −0.0017 | ||

| Roa | −0.0023 | −0.0024 | −0.0021 | −0.0023 | −0.0021 | −0.0022 | ||

| Growth | 0.0051 | 0.0053 | 0.0046 | 0.0049 | 0.0045 | 0.0045 | ||

| H10 | −0.0054 * | −0.0060 * | −0.0064 * | −0.0072 ** | −0.0065 ** | −0.0072 ** | ||

| MS | −0.0324 * | −0.0307 * | −0.0285 * | −0.0268 * | −0.0298 * | −0.0283 * | ||

| Area | 0.0058 *** | 0.0057 *** | 0.0051 *** | 0.0050 *** | 0.0053 *** | 0.0051 *** | ||

| IET | 0.0005 * | 0.0005 * | 0.0006 ** | 0.0006 ** | 0.0006 ** | 0.0006 ** | ||

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 0.0646 *** | 0.0640 *** | 0.0589 *** | 0.0581 *** | 0.0634 *** | 0.0627 *** | 0.0630 *** | 0.0623 *** |

| Adj R2 | 0.0029 | 0.0024 | 0.0106 | 0.0100 | 0.0186 | 0.0177 | 0.0166 | 0.0160 |

| F-statistics | 3.5479 *** | 3.0220 *** | 4.4774 *** | 4.2841 *** | 16.0552 *** | 17.949 *** | 15.5010 *** | 15.3338 *** |

| 1st Stage | 2nd Stage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| WIPA | DIPA | RESG | RESG | |

| CSE | 0.0144 *** (0.0016) | 0.2736 *** (0.0205) | ||

| WIPA | 0.0048 *** (0.0010) | |||

| DIPA | 0.0003 *** (0.0001) | |||

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | −0.9842 *** | −12.2941 *** | 0.0661 *** | 0.0655 *** |

| Adj R2 | 0.0879 | 0.0792 | 0.0151 | 0.0132 |

| F-statistics | 32.4016 *** | 29.0375 *** | 55.0501 *** | 49.3849 *** |

| J-statistics | — | — | 0.2970 | 0.8240 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RESG | RESG | PGDP | PGDP | RESG | RESG | |

| WIPA | 0.0048 *** (0.0010) | 0.0095 *** (0.0014) | 0.0042 *** (0.0010) | |||

| DIPA | 0.0003 *** (0.0001) | 0.0006 *** (0.0001) | 0.0003 *** (0.0001) | |||

| PGDP | 0.0571 *** (0.0123) | 0.0589 *** (0.0123) | ||||

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 0.0654 *** | 0.0648 *** | 0.2241 *** | 0.2221 *** | 0.0526 *** | 0.0517 *** |

| Adj R2 | 0.0153 | 0.013 | 0.4922 | 0.4896 | 0.0222 | 0.0208 |

| F-statistics | 60.7888 *** | 54.458 *** | 317.0343 | 313.7072 *** | 76.6030 *** | 72.4093 *** |

| Sample of Agriculture-Related Enterprises | Sample of Non-Agriculture-Related Enterprises | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| WIPA | 0.0045 *** (0.0010) | 0.038 ** (0.0017) | ||

| DIPA | 0.0003 *** (0.0001) | 0.0002 * (0.0001) | ||

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 0.0671 *** | 0.0066 *** | 0.0747 *** | 0.0759 *** |

| Adj R2 | 0.0141 | 0.0126 | 0.0044 | 0.0410 |

| F-statistics | 15.1199 *** | 14.6862 *** | 12.717 *** | 12.5814 *** |

| Sample of High-Tech Enterprises | Sample of Non-High-Tech Enterprises | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| WIPA | 0.0041 ** (0.0018) | 0.0049 *** (0.0011) | ||

| DIPA | 0.0002 * (0.0001) | 0.0004 *** (0.0001) | ||

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 0.0712 *** | 0.0698 *** | 0.0629 *** | 0.0626 *** |

| Adj R2 | 0.0103 | 0.0077 | 0.0140 | 0.0126 |

| F-statistics | 12.0060 *** | 11.7447 *** | 14.2689 *** | 13.9315 *** |

| Sample of Follow-Up Poverty Alleviation Plan Enterprises | Sample of No-Follow-Up Poverty Alleviation Plan Enterprises | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| WIPA | 0.0062 *** (0.0024) | 0.0057 *** (0.0013) | ||

| DIPA | 0.0006 *** (0.0002) | 0.0003 *** (0.0001) | ||

| Controls | ||||

| Year | ||||

| Industry | ||||

| Constant | 0.0686 *** | 0.0687 *** | 0.0574 *** | 0.0585 *** |

| Adj R2 | 0.0113 | 0.0122 | 0.0182 | 0.0110 |

| F-statistics | 13.2046 *** | 13.3708 *** | 13.4711 *** | 12.4831 *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, C.; Zhai, H.; Zhao, Y. Industrial Poverty Alleviation, Digital Innovation and Regional Economically Sustainable Growth: Empirical Evidence Based on Local State-Owned Enterprises in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15571. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315571

Lin C, Zhai H, Zhao Y. Industrial Poverty Alleviation, Digital Innovation and Regional Economically Sustainable Growth: Empirical Evidence Based on Local State-Owned Enterprises in China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(23):15571. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315571

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Chuan, Haomiao Zhai, and Yanqiu Zhao. 2022. "Industrial Poverty Alleviation, Digital Innovation and Regional Economically Sustainable Growth: Empirical Evidence Based on Local State-Owned Enterprises in China" Sustainability 14, no. 23: 15571. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315571

APA StyleLin, C., Zhai, H., & Zhao, Y. (2022). Industrial Poverty Alleviation, Digital Innovation and Regional Economically Sustainable Growth: Empirical Evidence Based on Local State-Owned Enterprises in China. Sustainability, 14(23), 15571. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315571