Evaluating Public Sector Employees’ Adoption of E-Governance and Its Impact on Organizational Performance in Angola

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Aims and Objectives of the Research

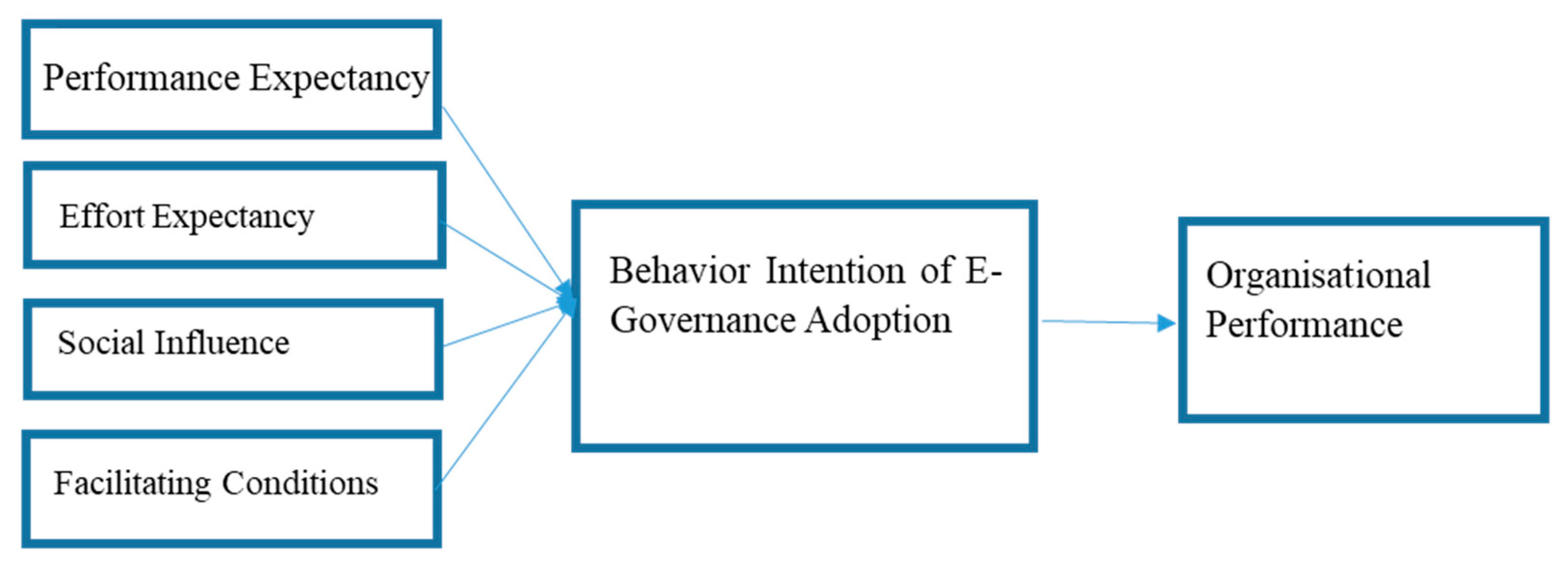

- To identify the factors (perceived usefulness, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions) that influence the adoption of e-governance in Angola’s public sector.

- To evaluate whether the adoption of e-governance in Angola’s public sector influences organizational performance.

- To highlight the mediating role of behavioral intention to adopt e-governance on the relationship between the acceptance factors (perceived usefulness, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions) and organizational performance.

3. Literature Review

3.1. Defining Organizational Performance

3.2. Defining E-Governance

3.3. Hypothesis Development

3.3.1. Mediating Effect of Behavior Intention of E-Governance Adoption between Performance Expectancy and Organizational Performance

3.3.2. Mediating Effect of Behavior Intention of E-Governance Adoption between Effort Expectancy and Organizational Performance

3.3.3. Mediating Effect of Behavior Intention of E-Governance Adoption between Effort Expectancy and Organizational Performance

3.3.4. Mediating Effect of Behavior Intention of E-Governance Adoption between Facilitating Conditions and Organizational Performance

4. Materials and Methods

5. Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

7.1. Contribution of the Research

7.2. Limitation of the Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arfeen, M.I.; Khan, N. Public Sector Innovation: Case Study of e-government Projects in Pakistan. Pak. Dev. Rev. 2009, 48, 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmad, N.; Waqas, M.; Zhang, X. Public Sector Employee Perspective towards Adoption of E-Government in Pakistan: A Proposed Research Agenda. Data Inf. Manag. 2020, 5, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Busaidy, M.; Weerakkody, V. E-government diffusion in Oman: A public sector employees’ perspective. Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 2009, 3, 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batara, E.; Nurmandi, A.; Warsito, T.; Pribadi, U. Are government employees adopting local e-government transformation? Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 2017, 11, 612–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank, A.D. South Africa. Retrieved from African Development Bank—Building Today, a Better Africa Tomorrow. Available online: https://www.afdb.org/en/countries/southern-africa/south-africa (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- Miller, J.C. Angola’s Past—A Short History of Modern Angola. By David Birmingham; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. Pp. xvi + 159. $29.95 hardback (ISBN 9780190271305). J. Afr. Hist. 2017, 58, 366–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekawani Lubis, P.H.; Utami, S. The Effect Of E-Performance on Organizational Performance Mediated By Employee Performance Discipline And Motivation: Study In Government Of Banda Aceh City. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Econ. Rev. 2020, 3, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johara, F.; Yahya, S.B.; Tehseen, S. Employee Retention Market Orientation and Organizational Performance—An Empirical Study. Int. Acad. J. Bus. Manag. 2019, 6, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Cho, B.S.; Choi, J.H. Relationship between high performance work systems and organisational performance: Focus on moderating effects of organisational culture. Product. Rev. 2015, 29, 143–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolade, D.A. Impact of Employees’ Job Insecurity and Employee Turnover on Organizational Performance in Private and Public Sector Organisations. Stud. Bus. Econ. 2018, 13, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gavrea, C.; Ilies, L.; Stegerean, R. Determinants of organizational performance: The case of Romania. Retrieved from ResearchGate Website. 2007. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227430479_Determinants_of_organizational_performance_The_case_of_Romania (accessed on 13 October 2022).

- Hanaysha, J. Examining the Effects of Employee Empowerment, Teamwork, and Employee Training on Organisational Commitment. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 229, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-dalahmeh, M.; Masa’deh, R.; Abu Khalaf, R.K.; Obeidat, B.Y. The Effect of Employee Engagement on Organizational Performance Via the Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction: The Case of IT Employees in Jordanian Banking Sector. Mod. Appl. Sci. 2018, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annarelli, A.; Nonino, F. Strategic and operational management of organizational resilience: Current state of research and future directions. Omega 2016, 62, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartnell, C.A.; Ou, A.Y.; Kinicki, A. Organizational culture and organizational effectiveness: A meta-analytic investigation of the competing values framework’s theoretical suppositions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Heeks, R. Understanding E-Governance for Development; iGovernment Working Paper no. 11; Institute for Development Policy and Management University of Manchester, Precinct Centre: Manchester, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelakantam, T. Corporate Governance in India—Issues and Challenges. Prabandhan Indian J. Manag. 2010, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, H.; Grönlund, Å. Future-oriented eGovernance: The sustainability concept in eGov research and ways forward. Gov. Inf. Q. 2014, 31, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, J. From single biobanks to international networks: Developing e-governance. Hum. Genet. 2011, 130, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saxena, K.B.C. Towards excellence in e-governance. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2005, 18, 498–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dash, S.; Pani, S.K. E-Governance Paradigm Using Cloud Infrastructure: Benefits and Challenges. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 85, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fedorko, I.; Bačik, R.; Gavurova, B. Effort expectancy and social influence factors as main determinants of performance expectancy using electronic banking. Banks Bank Syst. 2021, 16, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-L.; Yen, D.C.; Peng, K.-C.; Wu, H.-C. The influence of change agents’ behavioral intention on the usage of the activity-based costing/management system and firm performance: The perspective of unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. Adv. Account. 2010, 26, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabra, G.; Ramesh, A.; Akhtar, P.; Dash, M.K. Understanding behavioral intention to use information technology: Insights from humanitarian practitioners. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 1250–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, A.; Don, Y. Preservice Teachers’ Acceptance of Learning Management Software: An Application of the UTAUT2 Model. Int. Educ. Stud. 2013, 6, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sung, H.-N.; Jeong, D.-Y.; Jeong, Y.-S.; Shin, J.-I. The relationship among self-efficacy social influence performance expectancy effort expectancy and behavioral intention in mobile learning service. Int. J. u-e-Serv. Sci. Technol. 2015, 8, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakaranbank, S.; Vasantha, D.S.; Sarika, P. Effect of social influence on intention to use mobile wallet with the mediating effect of promotional benefits. J. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. 2020, 12, 3003–3019. [Google Scholar]

- Kulviwat, S.; Bruner, G.C., II; Al-Shuridah, O. The role of social influence on adoption of high-tech innovations: The moderating effect of public/private consumption. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed Dhaha, I.S.Y.; Sheikh Ali, A.Y. Mediating Effects of Behavioral Intention Between 3g Predictors And Service Satisfaction. J. Komun. Malays. J. Commun. 2014, 30, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hossain, M.A.; Hasan, M.I.; Chan, C.; Ahmed, J.U. Predicting user acceptance and continuance behavior towards location-based services: The moderating effect of facilitating conditions on behavioral intention and actual use. Australas. J. Inf. Syst. 2017, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, L.; Aklikokou, A.K. Determinants of E-government Adoption: Testing the Mediating Effects of Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Ease of Use. Int. J. Public Adm. 2020, 43, 850–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalaghi, H.; Khazaei, M. The Role of Deductive and Inductive Reasoning in Accounting Research and Standard Setting. Asian J. Financ. Account. 2016, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ketokivi, M.; Mantere, S. Two Strategies For Inductive Reasoning In Organizational Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2010, 35, 315–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al Awadhi, S.; Morris, A. Factors Influencing the Adoption of E-government Services. J. Softw. 2009, 4, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vorhies, D.W.; Morgan, N.A. Benchmarking Marketing Capabilities for Sustainable Competitive Advantage. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.; Priest, H.; Traynor, M. Reliability and validity in research. Nurs. Stand. 2006, 20, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, M.W. Exploratory Factor Analysis: A Guide to Best Practice. J. Black Psychol. 2018, 44, 219–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, D. Confirmatory Factor Analysis; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|

| PU | 0.776 |

| EE | 0.882 (EE6 was removed due to low reliability) |

| SI | 0.793 |

| FC | 0.822 |

| BI | 0.685 |

| OP | 0.914 |

| Code | Construct | Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | KMO | Eighen Value | Percentage of Total Variance | Factor Loading | Communalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE1 | Performance Expectancy | X2(6) = 289.864, p < 0.01 | 0.694 | 2.322 | 58.066 | 0.715 | 0.512 |

| PE2 | 0.725 | 0.525 | |||||

| PE3 | 0.817 | 0.667 | |||||

| PE4 | 0.786 | 0.618 | |||||

| EE1 | Effort Expectancy | X2(15) = 798.005, p < 0.01 | 0.880 | 3.788 | 63.139 | 0.798 | 0.637 |

| EE2 | 0.854 | 0.730 | |||||

| EE3 | 0.804 | 0.647 | |||||

| EE4 | 0.808 | 0.652 | |||||

| EE5 | 0.814 | 0.662 | |||||

| EE7 | 0.678 | 0.460 | |||||

| SI1 | Social Influence | X2(6) = 317.715, p < 0.01 | 0.773 | 2.472 | 61.809 | 0.724 | 0.525 |

| SI2 | 0.828 | 0.686 | |||||

| SI3 | 0.812 | 0.659 | |||||

| SI4 | 0.776 | 0.602 | |||||

| FC2 | Facilitating Conditions | X2(6) = 377.220, p < 0.01 | 0.763 | 2.578 | 64.465 | 0.801 | 0.642 |

| FC3 | 0.747 | 0.559 | |||||

| FC4 | 0.820 | 0.673 | |||||

| FC5 | 0.840 | 0.705 | |||||

| BI1 | Behavior Intention | X2(3) = 130.18, p < 0.01 | 0.668 | 1.841 | 61.368 | 0.602 | 0.776 |

| BI2 | 0.631 | 0.794 | |||||

| BI3 | 0.608 | 0.780 | |||||

| OP3 | Organizational Performance | X2(28) = 1069.87 p < 0.01 | 0.912 | 4.680 | 58.508 | 0.763 | 0.582 |

| OP4 | 0.752 | 0.566 | |||||

| OP5 | 0.762 | 0.581 | |||||

| OP6 | 0.760 | 0.577 | |||||

| OP9 | 0.729 | 0.531 | |||||

| OP10 | 0.746 | 0.556 | |||||

| OP11 | 0.802 | 0.644 | |||||

| OP12 | 0.802 | 0.643 |

| Model Fit Measure | Description | Pre-Determined Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Chi-square/df (CMIN/DF) | The Chi-square/df (CMIN/DF) represents the level of autonomy of the data with few differences. When the value of Chi-square/df (CMIN/DF) is closer to zero, the model fits more accurately. | <3 is considered to be good. However, if the value is <5, it is also acceptable. |

| The Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) | The approach used by the research to measure the congruence of the observed matrices covariance and the matrices that have been hypothesized. The index between 1 and 0.8 shows an acceptable fit model (Cheng and Assistant, 2011), while the value closer to zero depicts a poor model. | >0.80 = Acceptable. |

| Adjusted Goodness of Fit (AGFI) | The AGFI is similar to GFI. The values are asserted to be AGFI when the value of GFI has been modified based on the variable. When measuring AGFI, over 0.90 indicates a reasonably fitting model. | >0.90 = Acceptable |

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) | The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) is a rigorous calculation that shows the degree of disagreement between the conceptual perspective, the covariance algebraic expressions of the population, and the variable estimations. Values close to 1 are considered acceptable. Values below 0.8 are recommended for model fit, but values below 0.6 are normally preferred. | ≤0.08 = Acceptable |

| Root Mean Square Residual (RMR) | Root mean square can be explained when the residual covariance equals the square root of RMR. If the values are reduced, it represents a more accurate match. | ≤0.02 = Acceptable |

| Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) | The TLI is a relative measure of the model’s position along a continuous spectrum that is unchanged by the sample size. Commuting TLI is often preferred for a small sample size and values greater than 0.9 are considered appropriate. | >0.90 = Acceptable |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | The CFI measures the gap between the conceptual perspective and the empirical values after taking sample size into account. Values greater than 0.9 are considered appropriate. | >0.90 = Acceptable |

| Model | t | Sig. | Collinearity Statistics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tolerance | VIF | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 8.281 | 0.000 | ||

| Performance Expectancy | 2.452 | 0.015 | 0.465 | 2.151 | |

| Effort Expectancy | 1.029 | 0.304 | 0.311 | 3.218 | |

| Social Influence | 2.359 | 0.019 | 0.471 | 2.124 | |

| Facilitating Conditions | −2.218 | 0.027 | 0.287 | 3.480 | |

| Behavioral Intentions | 1.657 | 0.099 | 0.435 | 2.301 | |

| Correlations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Expectancy | Effort Expectancy | Social Influence | Facilitating Conditions | Behavioral Intentions | Organizational Performance | ||

| Performance Expectancy | Pearson Correlation | 1 | |||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | |||||||

| N | 273 | ||||||

| Effort Expectancy | Pearson Correlation | 0.696 ** | 1 | ||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | ||||||

| N | 273 | 273 | |||||

| Social Influence | Pearson Correlation | 0.549 ** | 0.656 ** | 1 | |||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||

| N | 273 | 273 | 273 | ||||

| Facilitating Conditions | Pearson Correlation | 0.665 ** | 0.785 ** | 0.680 ** | 1 | ||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| N | 273 | 273 | 273 | 273 | |||

| Behavioral Intentions | Pearson Correlation | 0.594 ** | 0.653 ** | 0.626 ** | 0.713 ** | 1 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| N | 273 | 273 | 273 | 273 | 273 | ||

| Organizational Performance | Pearson Correlation | 0.312 ** | 0.283 ** | 0.305 ** | 0.217 ** | 0.287 ** | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| N | 273 | 273 | 273 | 273 | 273 | ||

| Hypothesis | Accepted/ Rejected |

|---|---|

| H1. Behavior intention of adopting e-governance mediates the relationship between performance expectancy and organizational performance. | Accepted |

| H2. Behavior intention of adopting e-governance mediates the relationship between effort expectancy and organizational performance. | Rejected |

| H3. Behavior intention of adopting e-governance mediates the relationship between social influence and organizational performance. | Accepted |

| H4. Behavior intention of adopting e-governance mediates the relationship between facilitating conditions and organizational performance. | Accepted |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Congo, S.; Choi, S.O. Evaluating Public Sector Employees’ Adoption of E-Governance and Its Impact on Organizational Performance in Angola. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315605

Congo S, Choi SO. Evaluating Public Sector Employees’ Adoption of E-Governance and Its Impact on Organizational Performance in Angola. Sustainability. 2022; 14(23):15605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315605

Chicago/Turabian StyleCongo, Sergio, and Sang Ok Choi. 2022. "Evaluating Public Sector Employees’ Adoption of E-Governance and Its Impact on Organizational Performance in Angola" Sustainability 14, no. 23: 15605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315605

APA StyleCongo, S., & Choi, S. O. (2022). Evaluating Public Sector Employees’ Adoption of E-Governance and Its Impact on Organizational Performance in Angola. Sustainability, 14(23), 15605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315605