Climatic Elements as Development Factors of Health Tourism in South Serbia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

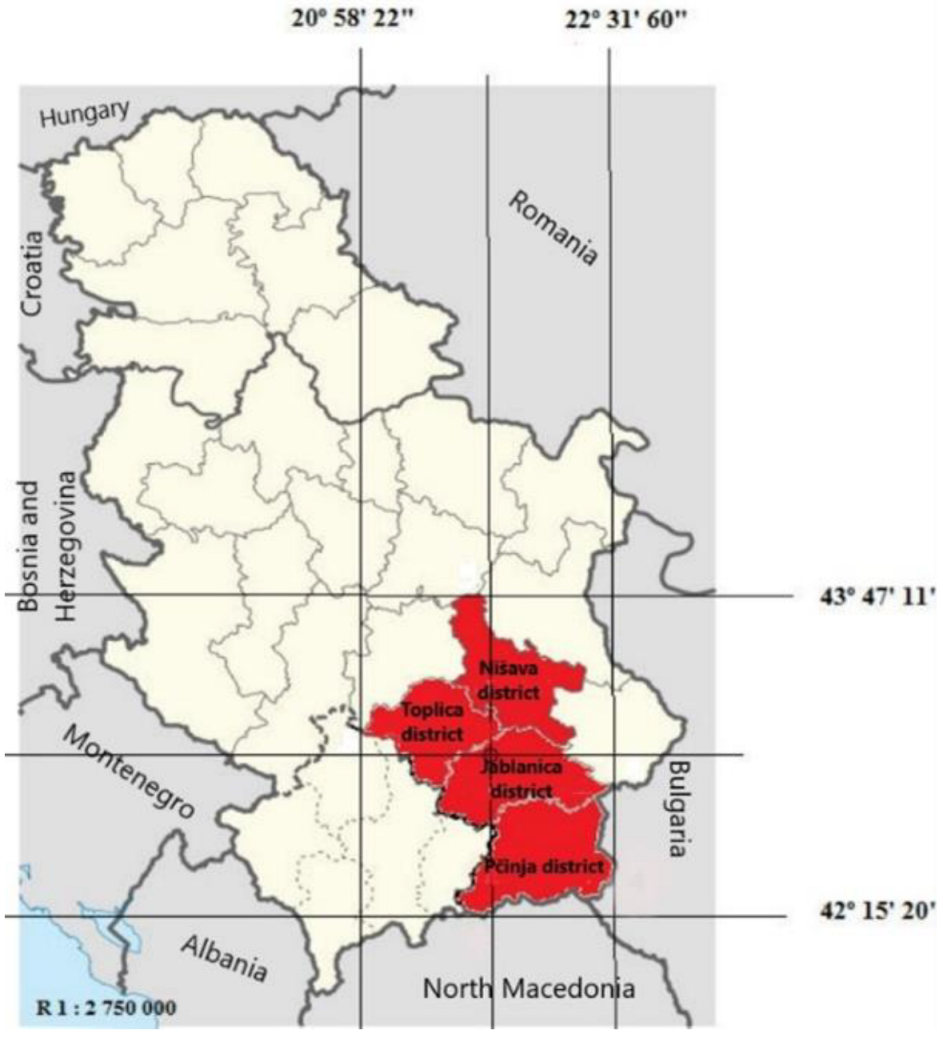

2.1. Case Study Region

2.2. Climate as a Development Factor of Health Tourism in South Serbia

2.3. Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Theoretical Implications

3.2. Practical Implications

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pessot, E.; Spoladore, D.; Zangiacomi, A.; Sacco, M. Natural resources in health tourism: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspar, C. Gesundheitstourismus im trend. Jahrb. Der Schweiz. Tour. 1995, 96, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Alfier, D. Tourism—A Selection of Papers; Masmedia: Zagreb, Croatia, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, N.; Zada, S.; Siddique, M.A.; Hu, Y.; Han, H.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Salazar-Sepúlveda, G. Driving Factors of the Health and Wellness Tourism Industry: A Sharing Economy Perspective Evidence from KPK Pakistan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, J.N.; Goodrich, G.E. Health-care tourism—An exploratory study. Tour. Manag. 1987, 8, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Health and medical tourism: A kill or cure for global public health? Tour. Rev. 2011, 66, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Kelly, C. Wellness Tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2006, 31, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeldner, C. 39th congress AIEST: English workshop summary. Rev. De Tour. 1989, 44, 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, H.; Kaufmann, E.L. Wellness tourism: Market analysis of a special health tourism segment and implications for the hotel industry. J. Vacat. Mark. 2001, 7, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.J.; Han, J.S.; Ko, T.G. Health-oriented tourists and sustainable domestic tourism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomić, E.H. Destinations of Health Tourism (With Reference to the Spas of Vojvodina); Prometej: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2006. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Houghten, F.C.; Yaglou, C.P. Determining lines of equal comfort. ASHVE Trans. 1923, 29, 163–176. [Google Scholar]

- Bedford, R.D. Urban Tarawa: Some Problems and Prospects; Department of Geography, University of Auckland: Auckland, New Zealand, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Fanger, P.O. Assessment of man’s thermal comfort in practice. Occup. Environ. Med. 1973, 30, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, V.S.; Qin, Y.; Li, G.; Jiang, F. Multiple effects of “distance” on domestic tourism demand: A comparison before and after the emergence of COVID-19. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 95, 103440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, C.; Bilal, M.; Jin, S. Fresh Air–Natural Microclimate Comfort Index: A New Tourism Climate Index Applied in Chinese Scenic Spots. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadafan, F.K.; Soffianian, A.; Pourmanafi, S.; Morgan, M. Assessing ecotourism in a mountainous landscape using GIS–MCDA approaches. Appl. Geogr. 2022, 147, 102743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmude, J.; Pillmayer, M.; Witting, M.; Corradini, P. Geography Matters, But… Evolving Success Factors for Nature-Oriented Health Tourism within Selected Alpine Destinations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieczkowski, Z. The Tourism Climatic Index: A Method of Evaluating World Climates for Tourism. Can. Geogr. 1985, 29, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, C.R. New Generation Climate Index for Tourism and Recreation; Berichte des Meteorologischen Institutes der Universität Freiburg: Freiburg, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, E.; Roth, R.; Lecomte, E. Availability and Affordability of Insurance under Climate Change. A Growing Challenge for the U.S.; Ceres: Boston, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, K.; Gao, J. Assessment of climatic conditions for tourism in Xinjiang, China. Open Geosci. 2022, 14, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, X. The Coastal Tourism Climate Index (CTCI): Development, Validation, and Application for Chinese Coastal Cities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukić, D.; Petrović, M.D.; Radovanović, M.M.; Tretiakova, T.N.; Syromiatnikova, J.A. The role of TCI and TCCI indexes in regional tourism planning. Eur. J. Geogr. 2021, 12, 006–015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojić, J. Valorization of the Economic and Geographical Resources of Southern Serbia in the Function of Tourist Development; University of Nis: Nis, Serbia, 2016. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Stanković, S. Spas of Serbia; Institute for Textbooks: Belgrade, Serbia, 2009. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Stanković, S. Spa Tourism in Serbia; Center for Culture “Vuk Karadžić” 239: Loznica, Serbia, 2005. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Spasić, T. 120 Years of Niška Spa, 1880–2000; Graphics Art 237: Niška Banja, Serbia, 2000. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Pavlović, M. Geographical Regions of Serbia 2—Mountain-Basin-Valley Macroregion; University of Belgrade, Faculty of Geography: Belgrade, Serbia, 2019. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Stankovic, S. Tourist Geography; Textbook Institute: Belgrade, Serbia, 2008. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia. Available online: http://www.hidmet.gov.rs (accessed on 25 September 2022).

- Anđelković, G.; Pavlović, S.; Đurđić, S.; Belij, M.; Stojković, S. Tourism climate comfort index (TCCI)-an attempt to evaluate the climate comfort for tourism purposes: The example of Serbia. Glob. NEST J. 2016, 18, 482–493. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlovic, T. The Sun and Photovoltaic Technologies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mirjanić, D.L.; Pavlović, T.M.; Radonjić, I.S.; Pantić, L.S.; Sazhko, G.I. Solar radiation atlas in Banja Luka in the Republic of Srpska. Contemp. Mater. 2021, 12, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- PVGIS. Available online: https://re.jrc.ec.europa.eu/pvg_tools/en/tools.html (accessed on 25 September 2022).

- Calderón-Vargas, F.; Asmat-Campos, D.; Carretero-Gómez, A. Sustainable Tourism and Renewable Energy: Binomial for Local Development in Cocachimba, Amazonas, Peru. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Solar Atlas. Available online: https://globalsolaratlas.info/map (accessed on 25 September 2022).

- Alonso-Pérez, S.; López-Solano, J.; Rodríguez-Mayor, L.; Márquez-Martinón, J.M. Evaluation of the tourism climate index in the Canary Islands. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Available online: https://www.stat.gov.rs/ (accessed on 25 September 2022).

- Stanković, A.M. Material basis in the function of future tourist development of the Pčinja district. In Proceedings of the 7th International Scientific Conference “The Future of Tourism”, Faculty of Hotel Management and Tourism, Vrnjačka banja, Serbia, 2–4 June 2022; pp. 112–130. [Google Scholar]

| Value of Index | Rating | Description | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| below 0 | VERY UNFAVORABLE | unpleasant and unfavorable | “snow“ activities |

| 0–20 | UNFAVORABLE | partly pleasant and favorable | excursions |

| 20–30 | FAVORABLE (between 24 and 28 VERY FAVORABLE) | pleasant and favorable | all tourism activities (except snow and extreme activities) |

| 30–40 | UNFAVORABLE | partly pleasant and favorable | recreational water activities (coastal, lakeside, spa tourism) |

| over 40 | VERY UNFAVORABLE | unpleasant and unfavorable | sunbathing, bathing (coastal tourism) |

| Tourist Destination | Elevation (m) | Month | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | X | XI | XII | ||

| Prolom banja spa | 560 | −11.21 | −5.82 | 4.51 | 12.19 | 22.06 | 28.25 | 39.64 | 40.02 | 29.75 | 17.29 | 0.24 | −9.11 |

| Sijarinska banja spa | 520 | −12.13 | −6.74 | 3.58 | 11.27 | 21.14 | 27.33 | 38.72 | 39.10 | 28.83 | 16.37 | −1.16 | −10.03 |

| Niška banja spa | 248 | −13.67 | −6.01 | 4.41 | 12.45 | 19.90 | 24.91 | 33.99 | 34.19 | 23.86 | 13.54 | −3.84 | −14.17 |

| Vranjska banja spa | 400 | −10.62 | −3.57 | 7.36 | 15.31 | 24.21 | 33.36 | 45.04 | 44.34 | 31.92 | 18.97 | 0.29 | −11.91 |

| Bujanovačka banja spa | 395 | −11.41 | −4.37 | 6.56 | 16.11 | 25.01 | 34.16 | 45.84 | 45.14 | 32.72 | 19.77 | 1.09 | −12.71 |

| Vlasina Lake | 1191 | −17.85 | −12.32 | −2.47 | 7.53 | 18.52 | 25.33 | 34.14 | 32.28 | 11.98 | 0.32 | −8.98 | −16.04 |

| Mountain Kukavica | 990 | −14.80 | −12.48 | 0.89 | 6.54 | 17.53 | 23.83 | 30.83 | 28.98 | 10.05 | 5.15 | −2.02 | −15.33 |

| Suva Mountain | 860 | −14.64 | −11.95 | 1.53 | 7.12 | 18.32 | 24.18 | 31.38 | 28.55 | 9.32 | 4.14 | −5.64 | −13.67 |

| Mountain Besna Kobila | 1310 | −18.23 | −19.98 | −9.34 | −1.02 | 9.24 | 16.24 | 25.11 | 26.66 | 7.66 | 2.58 | −4.46 | −17.93 |

| Vranjska Banja Spa | Niška Banja Spa | Prolom Banja Spa | Sijarinska Banja Spa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p1 | −447.2 | −813.3 | 169.9 | 235.9 |

| p1 (conf. int.) | (−598.8, −295.6) | (−3720, 2093) | (−259.9, 599.8) | (31, 440.8) |

| p2 | 904,800 | 1,651,000 | −327,200 | −468,700 |

| p2 (conf. int.) | (599,400, 1,210,000) | (−4,205,000, 7,508,000) | (−1,193,000, 538,900) | (−881,600, 0–55,870) |

| R2 | 0.8319 | 0.0426 | 0.0816 | 0.4298 |

| p-value | 0.0000912 | 0.542 | 0.394 | 0.0285 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marić Stanković, A.; Radonjić, I.; Petković, M.; Divnić, D. Climatic Elements as Development Factors of Health Tourism in South Serbia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15757. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315757

Marić Stanković A, Radonjić I, Petković M, Divnić D. Climatic Elements as Development Factors of Health Tourism in South Serbia. Sustainability. 2022; 14(23):15757. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315757

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarić Stanković, Anđelina, Ivana Radonjić, Marko Petković, and Darko Divnić. 2022. "Climatic Elements as Development Factors of Health Tourism in South Serbia" Sustainability 14, no. 23: 15757. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315757

APA StyleMarić Stanković, A., Radonjić, I., Petković, M., & Divnić, D. (2022). Climatic Elements as Development Factors of Health Tourism in South Serbia. Sustainability, 14(23), 15757. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315757