1. Introduction

Investments in sustainability, popularly known as ethical, responsible, environmental, social and governance (ESG) investments, have not stopped growing over the last decade [

1,

2].

Investors are no longer just looking for profitability, they also want to be part of the solution to the challenges facing society (climate change, poverty, inequality, social exclusion, etc.), meaning that they also invest in social and ecological awareness [

3,

4,

5].

ESG investments at the beginning of 2020 represented USD 35.3 trillion globally, which showed an increase of 15% over the last two years (2018–2020) and 55% since 2016, and represented 35.9% of total assets under management. In terms of the territories analysed in this paper, European ESG investments represented 41.6% of the total ESG investments and those from the USA represented 33.2% [

6].

However, the 2021 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warned that even in the best scenarios, it would not reach the objectives of the Paris agreement and that we are continuing on the trajectory of +3 °C, which is far from the commitment made in Paris (+1.5 °C) and places biodiversity and humanity at serious risk.

Moreover, to further complicate ecological transitions, the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020, which became the year of involuntary life changes.

COVID-19 has shown that societies can act with necessary force when required, but regulations and political will are needed. To confront COVID-19, governments worked quickly and in unison to limit or prohibit social and economic activities, even in the face of enormous economic impacts. As a result, during the second quarter of 2020, the S&P 500 Index dropped 34% [

7].

COVID-19 has highlighted the fragility of our global economy and societies [

8]. However, although nitrogen dioxide (NO

2 concentrations reduced in several cities by up to 60% compared to 2019 [

8] and house gas emissions (GHC) decreased by 10% in Europe [

9] and 11% in the USA [

10] during the first half of 2020, the post-COVID-19 data are not encouraging. With the return of social and economic activities, the concentrations of airborne pollutants have returned to pre-pandemic levels [

11].

Global governments wanted to stimulate their economies using economic stimulus plans, which were strongly restricted during the pandemic and caused the most significant recession since World War II [

12]. The European NextGenerationEU recovery package consists of EUR 750,000 million while the American equivalent consists of USD 4.5 billion, well above its European counterpart. Both stimulus plans emphasise their commitment to energy transitions and the opportunity to strengthen green objectives.

However, according to the OECD, only 21% of global stimulus plans have been allocated to ecological transition projects, with the remaining 79% of public funds going to projects that do not aim to solve climate problems [

13], which also emphasises that the current support for fossil fuels exceeds that for clean energy, hampering the efforts of the Paris summit.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that seven million people die each year from air pollution; however, the political and social ambitions following COVID-19 do not seem to work within the context of sustainability. The authors of [

14] argued that investors do not anticipate that the consequences of climate change will affect them since, in the short term, they affect geographies far away. This type of thinking ensures that financial systems fail in their responsibility in the face of climate change and that the inertia of financial markets means that, in the absence of legislation, economic systems are not able to redirect private capital away from fossil fuels. COVID-19 magnified this trend.

Nevertheless, several scientific papers have confirmed that during COVID-19, ESG investments outperformed traditional investments [

15,

16], validating research that has argued that ESG investments protect investors from economic and financial crises [

17,

18,

19,

20].

Due to the ambiguous signals that the markets and investors are sending about sustainable investments, this study wanted to understand whether the shareholders of the leading energy companies in Europe and the USA consider sustainability in their investment decisions. Furthermore, this study wanted to ascertain whether the COVID-19 pandemic, an unexpected, unpredictable and non-repeatable historical event, changed investment patterns of the leading energy companies in the USA and Europe towards sustainability, as uncertain contexts are known to make humans more irrational [

21].

So, we overviewed how high-volume positive, neutral, and negative sustainability news caused company share prices to fluctuate from 2017 to 2020, comparing the pre-COVID-19 periods (2017–2019) with 2020, the year the pandemic began. The research focused on the short-term market reactions that were associated with sustainability news, using the event study methodology. This statistical methodology is used to measure the impact of specific events on the value of companies: in this case, high-volume sustainability news. Shareholder reactions reflected how valuable sustainability news was in terms of their investment decisions.

We gathered several event studies analysing the tone of high-volume news (i.e., negative, neutral, and positive news), and the type of energy (renewable, fossil fuel or nuclear) for the periods before and during COVID-19.

The energy sector was chosen because it is the most strategic and central to the economy during ecological transition towards decarbonisation. However, fossil fuels remain the primary energy source, representing almost 70% of European energy production [

22] and 80% of American energy production [

23].

Europe and the USA were chosen as the markets for our analysis because they rank first when analysing the historically cumulative CO

2 emissions from fossil fuels [

24].

Today, when analysing CO

2 emissions per territory, we skip the historical responsibility of countries, such as those in Europe and the USA. Yet, in the context of climate justice, they are responsible for global cumulative CO

2 emissions representing 17% and 24%, respectively [

24].

Finally, the use of news as a source of information has empirically demonstrated that the media is correlated with variabilities in stock market prices [

25,

26,

27,

28].

This research contributes to the existing literature with a detailed sustainability narrative analysis of the energy shareholders of the two territories that have historically generated the most CO2.

By analysing two time periods (before and during the pandemic) and the three possible tones of the news (negative, neutral, and positive), we managed to reach a high level of understanding of the behaviour of the energy shareholders in the face of sustainability news. We identified incentives for greenwashing, distrust in renewable energies and behavioural changes during the pandemic.

Secondly, an analysis of 295,093 high-volume news items and 2134 event studies assured statistical robustness.

To the best of our knowledge, studies have yet to be published investigating the effects on the stock market’s capitalisation of sustainability news in such an exhaustive way. Previous studies have analysed the impact of sustainability or ESG news exclusively in some media, with more restricted concepts or hand-collected news [

29], making their results much less robust.

Finally, this information could be relevant to managers and boards of directors for designing and implementing effective ESG policies. Additionally, knowledge of the impacts of sustainability narrative could help legislators to develop incentives for shareholders that push for efficient ecological transitions.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. First, we discuss related work. Then, we present the materials and methods that were used in our study, followed by the results section and, ultimately, the discussion and conclusions section.

2. Related Work

Since the 1970s, the scientific community has searched for connections between CSR and corporate financial performance (CFP). However, early scientific studies considered investments in CSR as mere expenses that impoverished shareholders [

30,

31,

32]. Today, investments in ESG keep growing and numerous investigations have correlated CSR and ESG with higher returns [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37] and lower risks of market fluctuations [

38,

39,

40]. At the same time, other studies have found no benefits for shareholders from CSR and have even identified adverse reactions [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].

So, there is no current scientific consensus that investments in sustainability and CSR produce better financial performance. The authors of [

46] attributed this to the fact that the samples that were analysed were tiny and selected by hand and that not all of the available information was considered. The authors of [

47] attributed it to the fact that shareholders only think about economic benefits, separating the rest of the variables from their decision-making. The authors of [

36,

48] argued that the lack of consensus among researchers could be due to the wide range of metrics that have been used to measure financial performance and the broad range of CSR concepts.

However, there is a consensus that investors penalise companies more for irresponsible behaviour [

29,

46]. A clear example is the Volkswagen case and its scam surrounding the reporting of its vehicles’ emissions, which cost the company USD 33 billion [

49]. This relationship has also been noted in disasters, such as the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico (2010) and the nuclear accident at the Fukushima plant of the Tokyo Electric Power Company in Japan (2011). Shareholder overreactions to negative news has also been well researched by scientists [

28,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54].

Numerous studies looking at CSR and CFP have focused on CSR reporting [

33,

35,

36,

37,

55,

56] or the inclusion or exclusion of listed companies in sustainable indices [

34,

41,

46,

57]. However, these results could be biased. In CSR reporting, the companies themselves present the information and highlight their good actions [

29,

58], while the problem with sustainable indices is that existing evidence for ratings varies significantly for the same company between agencies [

59].

- ▪

In this research, we selected high-volume sustainability news as a source of information, since the media plays a crucial role in the ESG dialogue and is associated with fluctuations in stock markets [

28]. Furthermore, more and more scientific research has empirically demonstrated that ESG news directly impacts stock markets [

46,

60,

61,

62], especially negative news [

29,

40,

63].

The scientific literature has also analysed how the COVID-19 pandemic influenced the stock market returns of ESG factors. Again, there is no apparent unanimity among the studies on whether a higher ESG index could prevent the potential losses that are associated with COVID-19.

On the one hand, some studies proved that companies that bet on environmental and governance factors financially outperformed those with lower ESG indices [

64,

65,

66,

67,

68]. However, on the other hand, others argued that having a higher ESG index did not prevent financial losses during COVID-19 [

69,

70,

71]. Lastly, some studies found that shareholders preferred to make low ESG investments during the pandemic [

69,

72] as they did not immunise stocks.

The COVID-19 pandemic also hit the electricity market as electricity consumption fell to record levels due to the cessation of economic activities and lockdowns [

73]. The authors of [

74] analysed European electricity companies and their stock price responses to COVID-19. They confirmed that COVID-19 had negative impacts on the whole industry, especially renewable energy.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

The sample for this study contained all high-volume news that was digitally published worldwide that mentioned the leading European or USA companies in the energy sector and a combination of keywords related to sustainability, as displayed in

Table 1; for example, “Acea SP” + “gas” + “nitrogen oxides”.

The analysis period was from January 2017 to December 2020.

The databases that we used were the following:

The European and USA companies in Thomson Reuters’ top 100 global energy leaders (2019);

GDELT (Global Database of Events, Language and Tone);

Yahoo Finance.

To carry out the event study on the high-volume sustainability news samples, we first collected the following key information from the news: the date of publication, volume intensity (the combination of the number of times a news story was read and its media coverage), and the tone of the news (positive, negative, or neutral).

We obtained this information from the open-source news database GDELT package (GDELT Global Knowledge Graph (GKG) Version 2.0). For the tone of news, GDELT uses 51 data dictionaries, including the following popular dictionaries, highlighted in the literature: “Harvard IV-4 Psychosocial Dictionary” [

75], the “WordNet-Affect dictionary” [

76,

77] and the “Loughran and McDonald Sentiment Word Lists dictionary” [

78,

79].

The next step was to filter out the high-volume news, i.e., the news with a high-intensity volume. Therefore, to be part of the analysis sample, the intensity volume had to pass a filter of two standard deviations from the mean of all news, which represented 2.5% and 5% of the total sample. In this way, we guaranteed that we were analysing the tail of the distribution and only the news with the highest reach.

The date of publication of this high-volume news indicated the events that were analysed in this study, which had a total number of 295,093.

The next step was to group the high-volume news into the following categories: energy and sustainability keywords (for example, “petrochemical” + “footprint”) (

Table 1); market (i.e., the USA or Europe); period (i.e., before or during COVID-19); tone (i.e., positive, negative, or neutral).

The number of event studies that were gathered was 2134.

Table 2 and

Table 3 show how the event studies performed spread across the energy categories.

Following the method in [

80], an event study with less than 50 events was eliminated from the analysis to guarantee an acceptable sample size and the robustness of the statistical results.

3.2. Methods

To measure the economic impacts of the high-volume news, we followed the methodology of [

81]. As previous and numerous finance research concluded, capital markets reveal all possible information about companies in their stock prices. So, thanks to the event study methodology, one can analyse how a singular event alternates the company’s forecasts by quantifying the event’s impact on the company’s stock price. In the scientific literature, the most common way to perform this type of analysis is by using the stock returns, and, to a lesser extent, using volumes and volatilities. We studied Cumulative abnormal average returns (

CAAR).

The CAAR aggregates and cumulates the abnormal returns (AR) of all stocks n to find the average abnormal return at each time t. The AR are calculated by deducting the returns that would have happened if the studied event had not occurred (expected returns) from the actual returns of the stocks. While the actual returns can be empirically observed, the expected returns need to be estimated. For that, expected returns models must be calculated.

According to [

82], to determine the lead of events to analyse the

CAAR, the following characteristics should be considered:

Event date: In this case, the day of the publication of the high-volume news. When several news items described similar content within a 14-day window, the news with the highest volume intensity was used as the event date;

Event window: In this case, [–7, +7] days. This window was wide to collect all of the information that was emitted by different media;

Estimation window: In this case, we used a 110-day pre-period. For the calculation of the expected returns, the event study methodology used the actual returns of the estimation window;

Expected return model: The model we used for the CAAR was the market model, which has been widely accepted by the scientific literature and is the most commonly used.

The market model looks at the actual returns of a baseline reference market and tracks the correlations between company stocks and the baseline. Equations (1) and (2) were used to specify the model. The abnormal return on a particular day

ARit within the event window describes the difference between the actual stock return

Rit on day

t and the expected return, which is estimated based on two facts: first, the average relationship between the company stocks and the reference market (expressed by the

α and

β parameters) and, second, the actual returns of the reference markets expressed by

Rmt.

Then, to calculate the [−7, +7] event window, we used the following equations.

The cumulative abnormal returns (

CARit) value refers to the sum of abnormal returns (

ARit) over a given period of time, i.e., the [−7, +7] event window:

The average abnormal returns (

AARt) value aggregates the abnormal returns

ARit for all

n stocks to find the average abnormal return at each time

t:

The cumulative average abnormal returns (

CAARt) value, as illustrated in Equation (5), adds the average abnormal daily returns for the intervals within the event window:

The hypotheses of this study were analysed using a parametric test, i.e., the skewness-adjusted

t-test [

83], to correct any possibly skewed distributions of abnormal returns. As documented in [

84,

85,

86,

87,

88], stock returns are not normally distributed and tend to be skewed. The authors of [

89,

90,

91] suggested that this is because news increases the volatility of stocks, which magnifies their returns (especially negative news). Over 50 years ago, the authors of [

92] pointed out that the way investors interpret the information around them affects market efficiency.

In the case of this investigation, the returns were skewed as we performed event studies that were segmented by tone: the negative and neutral news items were negatively skewed, and the positive items were positively skewed.

The authors of [

93,

94,

95] found that the skewness-adjusted

t-test that was introduced by [

83] performed as well as equivalent non-parametric tests, as long as the sample size was not small.

Recalling the (unbiased) cross-sectional sample variance as:

Then, the skewness estimation that focused on average abnormal returns was specified by:

where:

and:

where

is the estimate of the coefficient of skewness and

is the conventional

t-statistic.

To conclude whether deviations from the CAAR were statistically significant, we used the skewness-adjusted t-test. We defined the results as follows:

The abnormal returns could not be distinguished from 0:

The abnormal returns could be distinguished from 0:

We decided to reject H0 when tskew > tcritical or the p-value < 0.05. This meant that the value was statistically significantly different from zero with a significance level of 5%.

This also meant that when tskew was greater than 1.96 or less than −1.96, we rejected that result, unless the result was not statistically different from zero.

4. Results

In this section, we discuss our results.

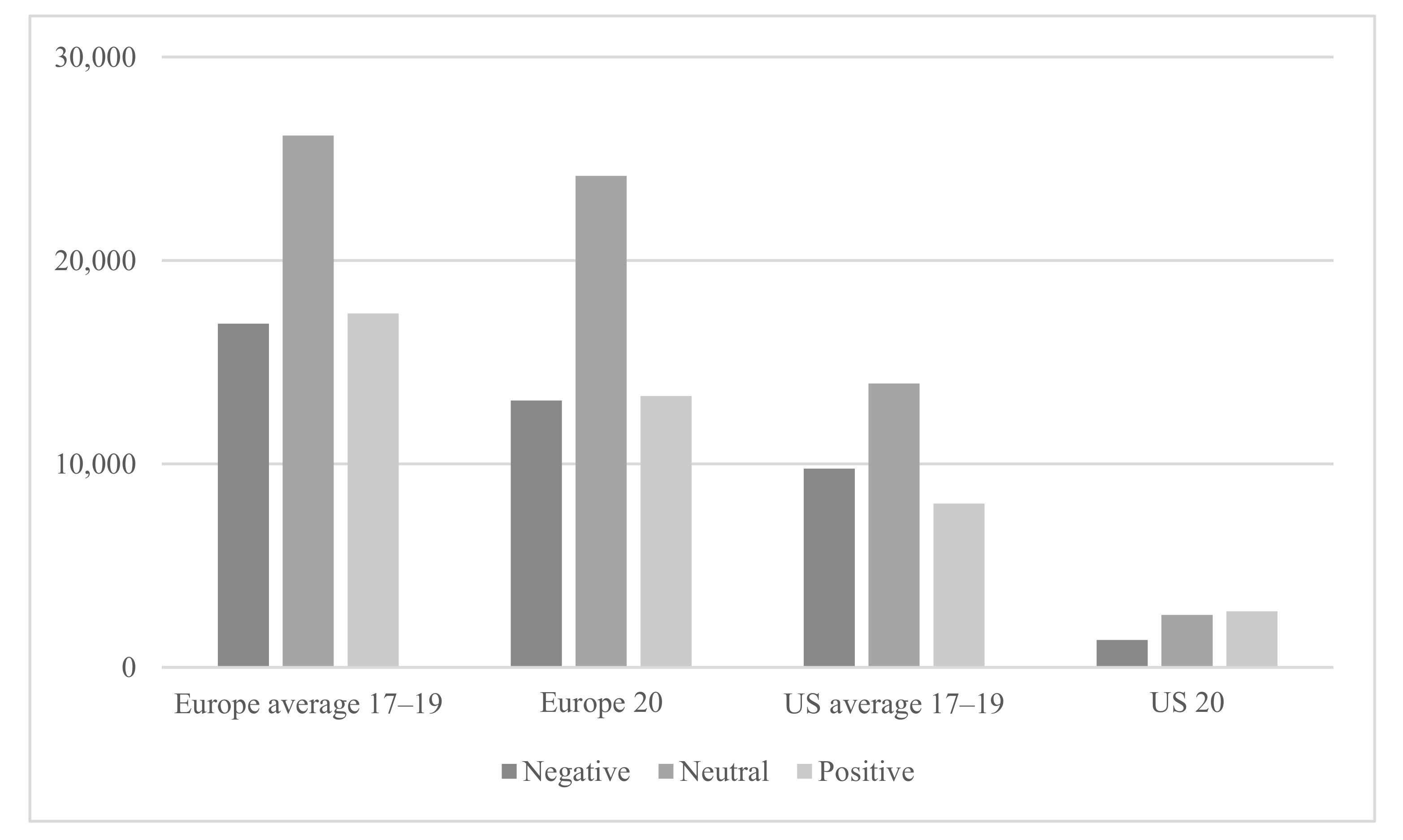

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 show the number of high-volume news items that were analysed. The distribution of all analysed news is represented in

Figure 1 and the distribution of all statistically significant news is shown in

Figure 2. In order to compare the periods, the annual average number of news items from 2017 to 2019 was calculated.

In

Figure 1, it can be observed that high-volume news about sustainability was more abundant in Europe than in the USA, both before and during COVID-19, but it was especially evident during the pandemic period.

However, as shown in

Figure 2, most of the analysed high-volume news items did not have statistically significant impacts on stock markets, representing just 10% of the total news.

However, we should note that during the pandemic period, the high-volume news had more influence, especially the negative and neutral news items in Europe and the positive and neutral news items in the USA.

We concluded that there were few viral sustainability news items that impacted stock markets. However, investors reacted more to them during the pandemic than in previous periods. In addition, Europe had a more negative bias, accentuating the negative and neutral news, while in the USA, we found the opposite, as there were more positive and neutral news items.

Table 4 and

Table 5 show the aggregation of the results from all significant event studies by territory (i.e., Europe and the USA), tone of the high-volume news (i.e., negative, neutral, or positive) and temporal period (i.e., before or during COVID-19).

These tables show the aggregated results of the skewness-adjusted t-test, the CAAR value, the p-value, the average number of high-volume news items analysed by each event study and the number of event studies used in each aggregation.

In

Table 4, which visualises the data from Europe, it can be seen that the only statistically significant event studies were those that were analysed as being negatively toned news during the pre-pandemic period.

It also should be highlighted that except for positive news items during the COVID-19 period, the other period and tones had negative skewness-adjusted t-test results, even though they were not statistically significant. Therefore, it could be concluded that Europe, in aggregate terms, tended not to react to sustainability news, even though the market showed a negative trend.

In the USA, however, the results were very different. We found statistically significant positive reactions during the pandemic period for news of all tones.

However, in the pre-COVID-19 period, we did not find any statistically significant results. Nevertheless, the sign of the skewness-adjusted

t-test was worth noting, i.e., negative for negative and neutral news and positive for positive news, which followed the classic pattern found by previous research [

23,

34,

38].

The results from the USA were striking as all news during the pandemic, regardless of the tone, caused a rise in stock market prices, which did not follow any previous patterns found in the existing literature.

By comparing the two markets, we could conclude that Europe was much more hostile towards high-volume sustainability news than the USA.

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 show that Europe had more news about sustainability than the USA, which was predominantly negative or neutral. Therefore, a possible explanation for the data observed in

Table 4 could be that the European media was more incisive towards sustainability and could negatively influence the markets.

Nevertheless, the positivity of the USA stock market towards sustainability news was very surprising. The fact that the event studies always found optimistic reactions, even when the news was negative, could indicate that sustainability news became less severe or that there were investment opportunities within the context of negative news about COVID-19. However, it should be noted that negative news items during the pandemic were the least frequent in the USA.

By analysing the results from the significant negative news items, the negative skewness-adjusted t-test results from Europe, which were in line with the previous literature, showed price drops in stock markets after negative news. However, surprisingly, the USA showed the opposite results during the pandemic.

Before the pandemic, the only negative news items in Europe that presented statistical significance were those dealing with nuclear energy, while during the pandemic, significant news items were those related to renewable energy. News items about fossil fuel energy did not show significant results, so it could be concluded that the markets did not react to negative news about fossil fuels. Nevertheless, we did not find any significant reactions in the USA before the pandemic. However, during COVID-19, negative news about fossil fuels and renewable energy, against all odds, obtained positive significance.

The results for significant neutral news items, as shown in

Table 8 and

Table 9, behaved similarly to those for negative news items, showing negative skewness-adjusted

t-test results with the exception of news items from the USA during the pandemic period, which produced positive results, as with the negative news items.

However, on this occasion, we did not find any items with statistical significance from pre-pandemic Europe and during the pandemic, only news items about nuclear energy were significant.

In the USA, on the other hand, before COVID-19, we found significant negative reactions to news about renewable and nuclear energy. In contrast, during the pandemic, positive reactions returned in the case of renewable energy.

Finally, by analysing the significant results from positive news items, as shown in

Table 8 and

Table 9, it was observed that the American market was much more optimistic than the European market, especially during the pandemic, presenting statistically significant results to news items about all types of energy. In Europe, however, we found negative reactions to news about nuclear and renewable energy during the pre-pandemic period, which were statistically significant.

Europe’s negative reactions to positive news items about nuclear and renewable energy could be because the shareholders of the companies in our sample were strongly linked to fossil fuels and see these alternative energy types as competition.

5. Discussion

After analysing the reactions of the American and European markets to significant sustainability news before and during the pandemic, it could be concluded that both markets were highly different, especially during COVID-19, when shareholders faced uncertainty.

The results showed that American and European energy shareholders had different reactions to the sustainability narrative. The American market changed during the pandemic to become much more optimistic. In contrast, the European stock market continued to be pessimistic, showing declines in prices even in the face of positive news items about nuclear and renewable energy.

This negative bias in Europe could have resulted from the mass media.

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 showed that Europe published more sustainability news, predominantly negative and neutral items. This constant media coverage could have encouraged investor pessimism, which was also accentuated during the pandemic. In the USA, as sustainability news was less frequent and was not negatively biased (rather, the opposite), the market reacted contrastingly.

These results could suggest two opposite things: the European narrative was more demanding for renewable energy than the American narrative or, alternatively, European shareholders penalised renewable energy in favour of fossil fuels, which American shareholders did not do to the same extent. Nevertheless, both markets agreed that nuclear power was still on investors’ agendas and that fossil fuels were less penalised by investors for negative or neutral news than other types of energy.

6. Conclusions

The authors of [

96] argued that investors do not anticipate the consequences of climate change since they will only occur in the future and far away from the West. Therefore, without legislation, shareholders will not change their way of investing simply out of conscience. Even so, the authors of [

15,

16] stated that sustainable investment funds outperformed traditional investments during the pandemic.

This research aimed to analyse the reactions of energy company shareholders to high-volume sustainability news before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our goal was to understand whether the sustainability narrative had comparable impacts on shareholders in both markets and whether the pandemic changed the way shareholders invest.

Understanding the shareholder’s narrative on sustainability in periods of stability and uncertainty allows us to better sense their biases and cultural differences.

Observing the results of this research, it was noticeable that shareholders did not penalise fossil energy companies for negative news as they did with other sectors. Furthermore, the pandemic changed how investors acted, and it did so oppositely in the two analysed territories.

Suppose we want to move towards an effective ecological transition. In that case, legislators must change, through laws, the incentives of shareholders so that it is not more profitable to invest in fossil fuels than in more efficient energy sources. Investors prioritise their benefits over sustainability. Only through change in legislation can shareholders’ narrative and profit optimisation strategies be directed towards pure ecological awareness.

The results of this research could be relevant to companies’ boards to better communicate their sustainability commitments. Additionally, for legislators, knowledge about the impacts of sustainability narrative on shareholders could make it possible to legislate new incentives and align them with the desired ecological transition goals.

Future research should perform regression studies to explain share prices through such means as, for example, using news volume intensity. That way, we could identify specific news items that impact stock markets and analyse their characteristics.

This research had some limitations. First, the analysed period, the year 2021, when the pandemic was still ongoing, was omitted. Future research could update the results and even add the year 2022 to investigate the effects of the Ukraine Invasion and the energy crisis.

Second, regarding the event study methodology:

The CAAR values could reflect more than just the result of the sustainability news (such as other events impacting these companies).

The event window could be challenged because long windows suffer from the confounding effects of other events, but shorter windows might not identify the real repercussions of media coverage.

The data dictionaries could have missed some keywords that might have created a more accurate narrative perspective.