1. Introduction

Tourism is an industry dependent on natural and cultural resources, specifically in rural areas where traditional attractions are less common. Rural tourism often involves visitation to natural areas, such as parks, nature reserves, or public lands, as well as agricultural activities, such as farm tours or wineries. Tourism is important to the economic growth strategies for disadvantaged areas that may have limited industrial options [

1]. Definitions of rural tourism can be viewed differently from country to country and region to region, as “some destinations may include only farm and nature attractions in defining rural tourism, while others may consider any economic activities that occur outside urban areas” [

1] (p. 1044). The United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) defines rural tourism as creating a rural environment for the visitor by offering a combination of natural, cultural, and human experiences which have a typically rural character; providing the visitor with authentic and traditional experiences which are the essence of rural life; bringing the visitor back to nature/the roots/basics, and embracing the return to origins and originality; comprising a spectrum of activities and services organized by the rural population which showcase rural life, art, culture and heritage; and is based on principles of sustainability. Thus, rural tourism encompasses small settlements, low populations, agrarian-based or natural resource-based economies, and traditional societies [

2], with activities often occurring outdoors in natural environments.

Natural disasters are increasing in quantity and intensity, directly impacting the ability of rural communities to rely on tourism as an economic growth strategy. According to The Economist [

3], the number of natural disasters globally has more than quadrupled since the 1970s. Woosnam and Kim [

4] show that hurricanes in the southern United States not only caused reduced visitation during the storm itself, but also produced structural damage that required extensive closures of national parks long after the events. When a tornado hit Thunderbird State Park in Oklahoma, revenue losses from park closures exceeded USD 50,000 [

5]. In 2017, Sonoma County wineries in California lost “

$38 million in sales, and an additional

$50–

$100 million in revenue due to facilities that needed to be repaired or rebuilt resulting from the wildfires” [

6] (p. 2477). Evidence suggests that regions with weaker economies, or those that are dependent on a single economy (such as tourism), are more heavily impacted by natural disasters, resulting in a longer recovery time, less resources to enable full physical recovery, and a larger relative loss of income than stronger economies [

7].

This paper looks at the impact of climate change, specifically wildfires, on southern Oregon’s Josephine and Jackson counties from the perspective of Airbnb hosts. What makes this study unique is that Airbnb hosts are both residents of these communities and active agents in the tourism sector. Moreover, rurality and nature are the primary attractions to the area [

8]. Therefore, wildfire has the potential to directly impact their personal property, their tourism business property (Airbnb accommodations), as well as their ability to earn income from decreased visitation. This paper will explain the impacts of climate change on the tourism sector generally, then present a qualitative case study to showcase the multifaceted aspect of wildfire on the livelihood of rural tourism providers.

2. Literature Review

Sustainable tourism studies have only recently recognized the impact of climate change on tourism economies. While the interactions between tourism and climate change first appeared in the literature in the mid-1980s [

9], the original Global Code of Ethics for Tourism, published in 1999, made no mention of climate change, which was also excluded from the Millennial Development Goals adopted by the United Nations in 2000. However, mounting pressure resulted in the first Conference on Climate Change and Tourism in Djerba, Tunisia in 2003 [

10], bringing climate change to the forefront of sustainability debates worldwide. Since that time, hundreds of peer-reviewed articles, public agency reports, and international news media have highlighted the unsustainable path of tourism, in part because of its hedonistic, resource-consumptive industry model [

11], and its reliance on unsustainable forms of transportation.

Climate change is the process of heating Earth’s atmosphere through the emission of certain gasses, including carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and fluorinated gases [

12]. These gases trap heat, causing a warming of the atmosphere, which in turn increases the water temperature in the oceans, resulting in a change of weather patterns and an increase in extreme weather events across the globe [

13]. Extreme weather events increase risk to crop-production and require the adaptation of innovative management strategies to mitigate risk [

14]. The travel and tourism industry is responsible for about 5 percent of yearly greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) [

15], which makes it both a contributor to climate change and a recipient of the negative consequences of climate change.

Currently, research related to climate change and tourism is growing. Much of this research focuses on beach communities and global sea rise, which leaves coastal areas particularly vulnerable. For example, a review of climate literature found both marine environments and land environments will lose attractiveness because of a loss of native species, an increase in exotic invasive species, the degradation of landscapes, decreased comfort due to beach availability reduction, increase in health issues due to emergent infectious diseases, infrastructure decline, drinking water shortages, and a loss of cultural heritage. There is also acknowledgement of increased risks of wildfire and coral reef bleaching [

16]. Klint et al. [

17] argue that the priority of coastal resorts is to maintain ocean views, expansive beach access, and the aesthetic qualities desired by international tourists, rather than mitigation strategies designed to protect the long-term viability of tourism. Along the Mediterranean coast of Egypt, evidence suggests that the “assessment of the existing adaptive measures in the area indicates their inadequacy to face… natural risks such as storms and tsunamis as the existing coastal protection hard engineering constructions were established in a fragmented manner [

18] (p. 1161).

Additional research has investigated the potential of climate change impacts on winter outdoor recreation locations. Ski resorts are reporting lower snow levels and shorter seasons, requiring extensive snow making technologies [

19]. National parks and nature areas are recording record glacial loss, biodiversity loss, and long-term drought, increasing fire risk. Urban areas are not excluded from the dangers. Lopes et al. [

20] provide evidence that extended heat waves along the Iberian Peninsula have made outdoor activities, including city tours, highly uncomfortable. They conclude, “The absence of adaptation actions means that there is no accountability of the responsible entities to create measures and strategies capable of mitigating any extreme effects caused by climate change” (p. 14). As South Africa focuses their climate change agenda on rural areas, business tourism to Johannesburg will be drastically impacted as heat and humidity increases make the city vulnerable to “higher costs of living, threats to water supplies, possible impacts on power supplies and deterioration of air quality” [

21] (p. 232).

Literature on the impacts of wildfire on tourism is less common. Between 2000 and 2019, the number of wildfires in the United States reached 72,400 annually, burning approximately 7 million acres each year, up from 3.3 million, on average, in the 1990s [

22]. Not only does the direct threat of fire danger cause economic disruptions, smoke and small particulate matter can render air quality unhealthy, forcing people to remain inside and limiting physical activities when outdoors. Srinamphon, Chernbumroong, and Tippayawong [

23] found that “financial factors (accommodation, travel agency business, and souvenir businesses) were severely affected due to lower revenues and higher business costs during the period…of high particular matter from agricultural burning and wildfire” in Thailand. In fact, Bacciu et al. [

24] argue that increasing wildfires is one of the most critical aspects of climate change on the tourism economy in the Mediterranean region.

Evidence suggests that visitor perceptions of destinations are both positively and negatively impacted by natural disasters. Habitat loss, including native animals and landscapes, could result in a substantial decline in visitation. For example, it is predicted that a 20–43% decline in visitation to Lijiang, China could occur if local glaciers were to melt and that 76% of diver tourists in Bonaire would not return at the same price if severe coral bleaching occurred [

9]. In relation to wildfires, data from potential tourists to the California wine region affected by fires in 2017 showed ‘support through visitation’ was a common response theme immediately following a highly publicized wildfire [

6]. However, another study shows that visitation potentially decreases during a wildfire, increases shortly after the event, and then experiences a long-term decline based on the amount of residual damage [

25].

In conclusion, Scott, Gössling, and Hall [

9] claim that climate change will affect the future prospects of international tourism. First, direct climatic impacts will transform the seasonality of many destinations, increase operating costs, impact the location and design of tourism services, destroy or disrupt infrastructure and business operations, alter destination attractiveness, and influence tourist demand and destination choice. Second, indirect climate-induced environmental change will alter the ability of businesses and policy-makers to establish effective sustainability initiatives. Environmental change will be coupled with indirect climate-induced socioeconomic changes, such as a decrease in economic growth and discretionary wealth, and an increase in political instability and security risks. Lastly, they claim that the policy responses to climate change could increase transport and insurance costs, and challenge existing water rights in tourism destinations. Therefore, the research question for this study is ‘how does wildfire impact Airbnb visitation, host operations, and the vitality of rural tourism’.

3. Materials and Methods

Airbnb hosts provide a unique lens through which to better understand the impacts of climate change on rural communities facing fire threats in the western United States. Not only do these hosts feel the economic impacts of reduced tourism visitation during and after such events, but they are also at risk of losing their personal property, including their Airbnb properties. As residents of the community, wildfire impacts all of them through personal risk or risk to loved ones and valued community members.

Using a constructivist perspective, this paper situates the researcher within the context of the challenges facing tourism providers, specifically Airbnb hosts [

26], due to increasing risks related to climate change. The case study format permits the examination of a specific bounded unit of analysis as a means to encapsulate variable conditions to explain ‘what’ and is happening rather than ‘why’ it is happening [

27]. By describing the shared experience of the interview participants, a better understanding of the impacts of climate change on southern Oregon can be realized. The author acknowledges that this study is not generalizable across research sites.

Qualitative methods were used to evaluate the perceptions of wildfire risk to tourism held by Airbnb hosts between January and June 2022. First, the author attended two community meetings held on Zoom. These were hosted by the governor of Oregon, local firefighting organizations, and local community leaders (city and county officials) and included the presentation of the Oregon Wildfire Senate Bill 762 (see

https://www.oregon.gov/odf/pages/sb762.aspx, accessed on 30 September 2022). Notes were taken during the open comment session, which informed the interview questions. Next, eight interviews were conducted in southern Oregon. Contact was made through the Airbnb listing site, where the researcher sent inquiries to hosts within Josephine and Jackson counties as these two counties recently declared a state of emergency related to drought conditions and the threat of wildfire [

28]. Hosts then responded to these initial inquiries. From there, snowball sampling was used to recruit additional participants.

Table 1 shows the participants.

In order to avoid corporate-owned hosts that may be unaware of local issues [

29], hosts were required to manage the daily operation of their listings and could not manage more than 2 properties. One-on-one semi-structured interviews were conducted over Zoom and lasted about 1 hour each. All interviews were transcribed using an online transcription program, and participants were offered an opportunity to review all transcripts. All interview data were combined and then coded into topics, which were guided by the literature review of extant studies related to natural disasters and tourism [

30] using NVIVO software. The topics were then combined to develop themes, which are presented below.

4. Results

Four themes were discovered through the coding process: two seasons; a government’s response; politics, politics, politics; and tourism challenges. Academic literature, news articles, and community meetings are used to situate the results within a theoretical discussion.

4.1. Two Seasons

Unlike hurricanes or tornados, where a disaster usually lasts a few hours or a day, a wildfire can burn for months, and a fire that is under control can jump the containment lines or send embers miles away to start new wildfires. The result is that once a fire starts burning, the smoke can last until the rains comes. David reflects on the Almeda Fire, which burned the towns of Talent and Phoenix in Jackson County, Oregon in 2021 “the fire burned 3200 acres and destroyed 3000 structures in a matter of hours. We all know someone who lost their home or business. It was a real wake-up call. We are only 30 miles from California, but we all thought we were immune. Not any more”. Francis adds, “a fire that starts in early August will burn until October, until we have a few days of solid rain. Not only are people evacuated for the whole time, but the smoke from a single fire will ruin the entire tourist season. Smoke reminds us of our vulnerabilities. It can be very scary, especially for our visitors”.

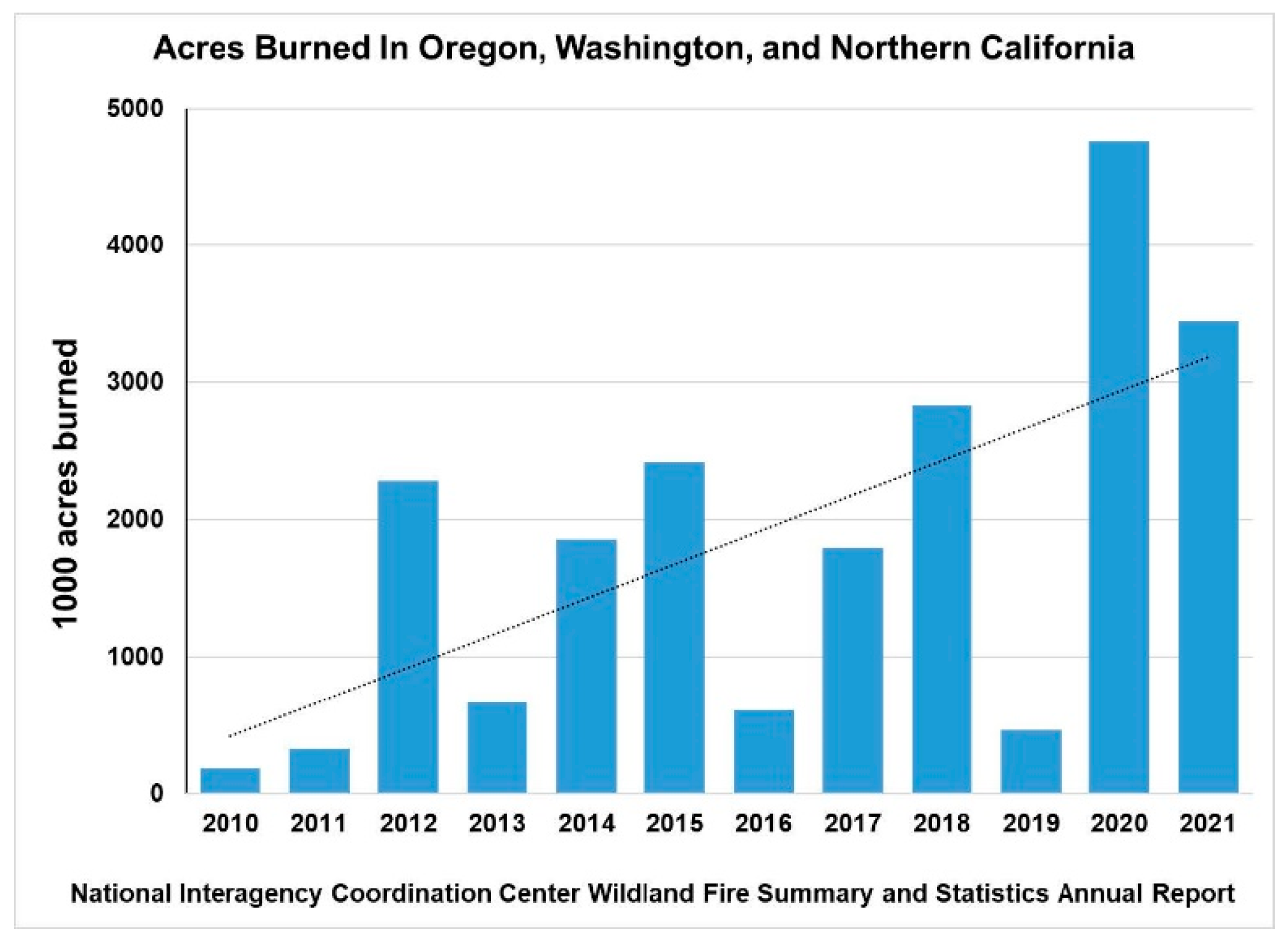

Colloquially, southern Oregon has two seasons, the rainy season and the smoky season. Evidence suggests that the rainy season is getting shorter and the smoky season is getting longer [

31], and, as a result, the amount of acreage burned from wildfire is on the rise (see

Figure 1). Camille remembers, “we used to worry about floods, fires did happen, but they were rare. We haven’t had a significant flood in these areas since the big one in 1996”. Betty adds, “We used to have smoke when a big fire was burning in California or nearby, but now it seems like the smoke starts in July and doesn’t leave until October”. In fact, the City of Medford recorded 26 days in 2021 where the air quality was considered ‘unhealthy’, and the city of Klamath Falls recorded 41 such days [

32]. Additionally, Greggory notes, “we used to have maybe a week of 100+ degrees (38 degrees Celsius), this past year we had over 100 degrees in April, and I can’t even tell you how many days it was scorching hot this summer”.

Oregon also claims two tourist seasons, summer and fall. Summer has traditionally seen the arrival of the general outdoor enthusiast who raft the Rogue River, hike the mountain trails, or visit a number of local festivals and wineries. In the fall, the Chinook salmon run and hunting for deer and duck is a prime motivation to visit the area. While there is a ski resort in Ashland, visitation is generally concentrated at the resort during the winter. However, wildfire smoke has had a direct impact on visitation during the late summer and early fall months. Harriet remarks, “once the smoke gets to unhealthy levels, I have to inform my guests. If they have asthma or something, it could be deadly for them. I would say more than half cancel once the smoke is really bad”. David notes, “who wants to be running around outside if you can’t breathe? Our guests are generally active and want to be out in nature”.

4.2. A Government’s Response

Oregon is recognized as a leader in sustainable development in the US. In fact, based on an assessment of water, air and soil quality, renewable energy, and auto fuel use metrics, Oregon ranks number 1, in part because 49% of its energy comes from renewable sources [

33]. The 2018 Sustainability Plan has prioritized energy and greenhouse gas management, water conservation, waste reduction, fleet management focused on fuel efficiency and emissions reductions, integrating sustainability into construction projects and real estate decisions, and strategic sustainability-oriented procurement decisions within the state government operations [

34]. In spite of these efforts, Oregon is facing unprecedented drought conditions. At the time of writing, 70% of Oregon is experiencing moderate drought, 52% severe drought, and 30% extreme drought, with 2022 receiving the lowest amount of rainfall in the past 128 years. As a result, 23 counties in Oregon have declared a state of emergency related to drought conditions [

35].

Senate Bill 762 is legislation designed to provide more than USD 220 million to help modernize and improve wildfire preparedness by: creating fire-adapted communities, developing safe and effective response, and increasing the resiliency of Oregon’s landscapes [

36]. At the time this research was conducted, the participants were anxiously awaiting the fire map, as designated in the Oregon Wildfire Senate Bill 762. In short, the wildfire map was to be a GIS-derived assessment of the wildfire risk for every property in Oregon. Greggory states, “Once we are designated a wildfire risk, there’s a good chance insurance companies will increase our rates. They don’t need an excuse, but a wildfire rating gives them one anyway”. David adds, “In rural California, so many of the insurance companies have pulled out. I looked for property there, but the California state (provided) insurance for wildfire in outrageously expensive. It’s like four times what I pay here in Oregon”. There is concern that new construction will require fire-resistant building materials within certain map designations (high-risk and above), which increases the expense related to home construction and improvement. For example, Betty has been refurbishing her Airbnb property located in a heavily forested area north of Grants Pass. She explains, “I just replaced the siding because once the regulations take effect, fire resistant siding will be out of my price range. I did put on a metal roof, more as a fire precaution than anything else”.

Senate Bill 762 also provides resources for homeowners. Camille has already looked into grants to support property clean up. “If I can get a few thousand dollars, I can remove the trees around my home and my Airbnb property to make them safer. Most of the pines are dying anyway from invasive species (specifically Pine Beetle, known as Dendroctonus ponderosae), but I can’t afford to remove them all myself”. Harriet has looked into site hardening, a process of removing flammable vegetation and replacing it with gravel, concrete, or sand. She adds, “I am anxious for the educational resources and the funding that helps us be safer. There are many choices. It needs to be inviting for our guests, but safe also”.

It is important to note that at the time of writing, the fire map, which had received extensive criticism by property owners, and has been rescinded, pending further review. As stated in the Oregonian, “The mapping effort identified some 120,000 tax lots across the state at “high” or “extreme” risk of burning, and some 80,000 properties that would be subject to new building code requirements” [

37].

4.3. Politics, Politics, Politics

As fire risk grows, so does the conversation surrounding human-caused climate change. As an area that identifies as conservative, there are still community debates about whether climate change should be a political objective. During the Zoom community meetings, many residents expressed the politization of climate change, arguing that most fires are started by lightning or arson, not climate change. Others argued that regardless of the cause of fires, extensive drought has exasperated the spread of wildfire, causing rapid intensification resulting in death and large-scale destruction. This debate has influenced the participants’ perception of climate change. Alex explains, “I don’t know what causes the changing weather patterns, but it only makes sense that all our pollution has some impact. I mean, I know science has an agenda, just like the politicians, but it’s getting harder to explain the severity of these events”.

The increased political tensions challenging the United States are also felt in southern Oregon. Oregon has invested extensive resources in climate change mitigation, resources that have become more controversial post-COVID. Greggory argues, “Forestry and lumber are the backbone of these communities. Once the democrats destroy the coal industry, they will be after us next”. Betty expands, “We have managed our land for generations. We don’t need government stepping in to tell us what to do. It’s not government’s job to tell us how to manage our property”.

Issues such as homelessness, crime, illegal drug trafficking (and the associated human trafficking) are other issues requiring resources. Alex sums it up by saying, “the post-COVID world is a mess. Our students’ education is suffering, crime is rampant and law enforcement is fighting budgeting reductions. Mental health and homelessness are everywhere. Fire is scary and inevitable in places like southern Oregon, but forcing homeowners to improve their property isn’t the best use of our tax dollars”. Moreover, 53% of the total land in Oregon is owned by the federal government, over which state and local authorities have no jurisdiction [

36].

A quick review of issues in the upcoming midterm elections (the non-presidential elections where many members of congress, state legislatures, and governors are elected), wildfire mitigation is a frequent topic of discussion, yet climate change is not [

38]. For example, of the three gubernatorial candidates, all support additional resources for fighting wildfire, but two oppose climate change legislation and one supports it. Camille argues, “how can you support resources for firefighting, but not to stop the cause of the fires. It’s just politics at its worst”. Of the participants that believe humans have caused climate change (63% of the participants), all were concerned that Oregon’s lead in sustainability could easily be overturned if a climate denier is elected. Those that were unsure about or deniers of climate change (38% of the participants) did not mention climate legislation as a concern, only wildfire legislation.

4.4. Tourism Challenges

While logging and lumber are the economic heritage of the area, tourism is the future. COVID-19 had a devastating impact on the tourism economy in 2020, yet visitation increased 71% in Jackson County and 77% in Josephine county in 2021, of which a majority of that growth occurred in private home rentals (such as Airbnb) [

39]. Moreover, “the travel industry is one of the three largest export-oriented industries in rural Oregon counties” [

8]. However, restrictions in natural areas, closures, and smoke have had an impact on the visitation, as perceived by the study participants.

Multiple respondents noted that the smoke coincides with the busy tourist season, and while they all breath a sign of relief when the rains come, they also recognize their revenue stream has dried up. Betty notes, “I still have to pay my property tax on my Airbnb property. If I don’t earn money in the summer, it’s a real struggle the rest of the year”. Visitors that do arrive during the smoke season often have negative experiences when participating in outdoor activities. For example, Alex notes, “The Hell Gate boat rides are probably the biggest draw to the area. But standing in line for an hour, then spending the day breathing all that smoke has left many of my guests frustrated”. Emily adds, “I’ve noticed a decrease in return visitation when someone has a bad air quality experience. I track that stuff pretty closely”.

Moreover, restrictions, such as a ban on campfires, the use of power tools and guns, and smoking in nature areas have frustrated many campers and hikers. Harriet often gets visitors before a 3-day raft trip down the Rogue River, and claims that sometimes her guests are scared of the smoke. She says, “it like the threat of wildfire is in your face. You can’t ignore that you are headed into the wilderness and fire is a real possibility while you are there”. In the past, hunting season started after the rains, but as the summer has lengthened, some hunting areas remain closed as a wildfire precaution until three or four weeks into the season. Francis allows hunting on his property for a fee, but is finding that the shorter season, because of ammunition restrictions during fire season, is hurting his business.

5. Discussion

This paper had shown the impact of wildfire on rural tourism from the perception of Airbnb providers. Southern Oregon, as a nature-based tourism destination where resource extraction has been a traditional driver of the economy [

1], outdoor recreation and tourism services have provided new avenues of economic activity, specifically within the sharing economy [

8]. However, southern Oregon faces new threats from extensive drought conditions. Not only does wildfire endanger the vitality of the tourism industry [

16], residual smoke from fires outside the area is also impacting visitation to the area. As the smoky season get longer and the amount of rain decreases over the winter [

31], wildfire has become a regular part of life in Oregon. Moreover, in support of Woosman and Kim [

4], wildfires not only reduce tourism during an active fire, but residual smoke can limit visitation in areas where wildfires are not currently burning or where wildfires are under control.

As in many destinations, accountability remains obscure [

20], as over one-third of the respondents either did not believe or were unsure if climate change is a human-caused phenomenon. While climate change remains politicized in southern Oregon, fire mitigation strategies are prioritized over general climate policy, a far too common occurrence in many tourism destinations [

24]. Although Oregon remains a leader in sustainable energy production, much of that is influenced by a more liberal population located outside the conservative rural counties. One could argue that climate change is a global phenomenon, and, therefore, the impacts of global greenhouse emissions are manifested as wildfires in Oregon, resulting in a more pronounced policy focus on forest and fire management. On a positive note, while the adaptive measures encouraged in the Oregon Wildfire Senate Bill 762 do not mention tourism facilities specifically [

18], the policy direction may be leading Oregon into a more resilient tourism industry, as much of the economic damage comes from the extensive reconstruction of infrastructure after a fire event [

6].

Smoke appears to be the leading cause of tourist cancellations, as noted by the Airbnb property owners. Small particular matter resulting from near-by fires makes outdoor activities more dangerous and less enjoyable [

22]. Poor air quality also seems to reduce visitor satisfaction, resulting in a decrease in return visitation. As travelers become less sensitive to tragic natural disasters highlighted in the media, ‘support through visitation’ is less likely to occur [

25], implying any serious fire to southern Oregon’s tourism resource could have devastating effects over the long run.

This research supports Scott, Gössling, and Hall’s [

9] claim that climate change has a definitive impact on tourism. Seasonality of tourism has already been affected as summer grows longer and hotter, interrupting the hunting and fishing season. Operating costs are increasing for Airbnb hosts as regulation requires fire-resistant building materials and ground-cover site hardening for any new construction or remodel projects. Wildfire and smoke have also impacted visitor satisfaction and destination attractiveness. Moreover, socio-economic changes are occurring as the political battle over climate change legislation intensifies. Lastly, the policy response has focused on fire mitigation at the expense of a more overarching response to climate change. As drought and wildfire dangers increase, the impact to tourism will only worsen, as outdoor recreation and the rural character of southern Oregon become victims of climate change.