Spillover Connectedness among Global Uncertainties and Sectorial Indices of Pakistan: Evidence from Quantile Connectedness Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

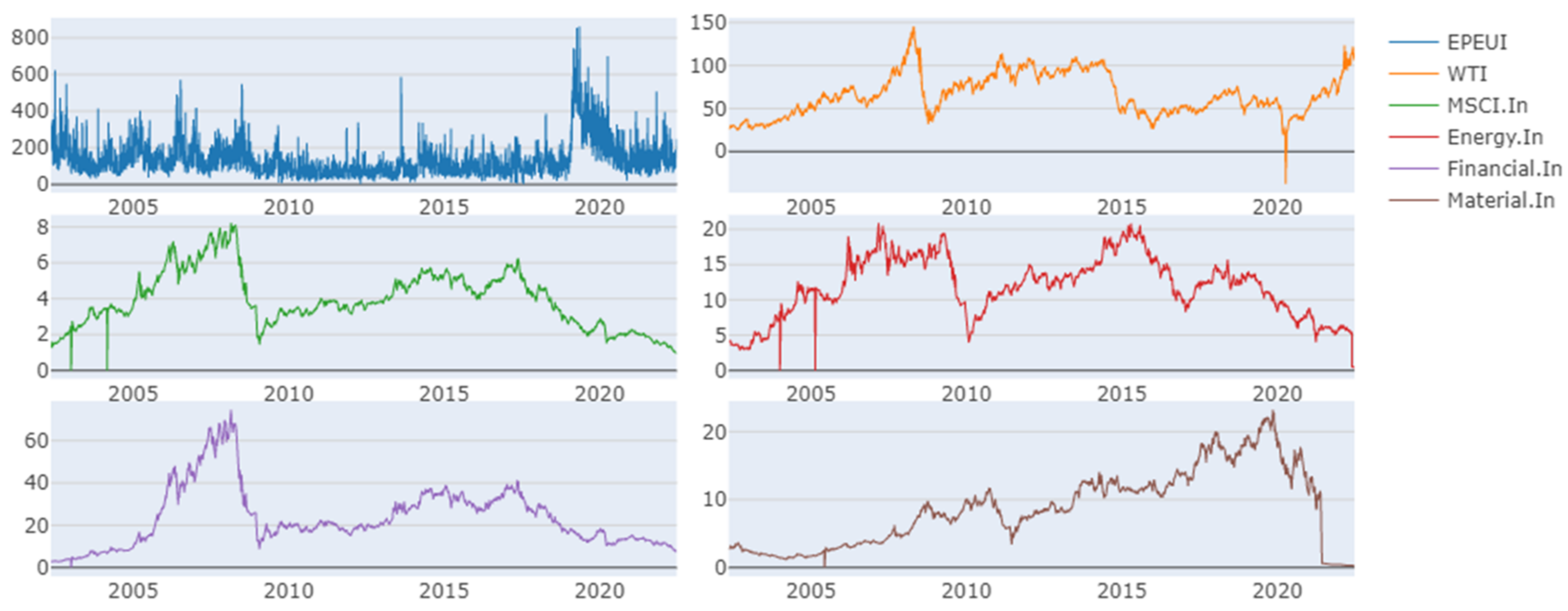

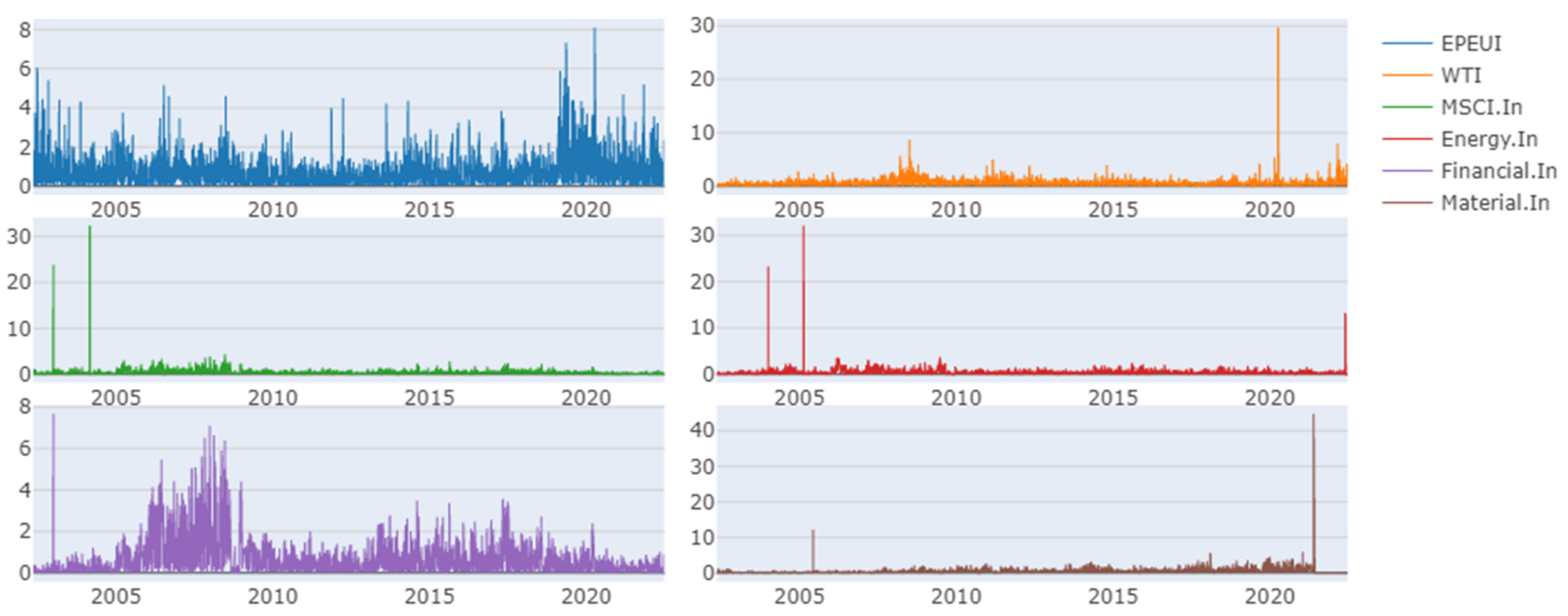

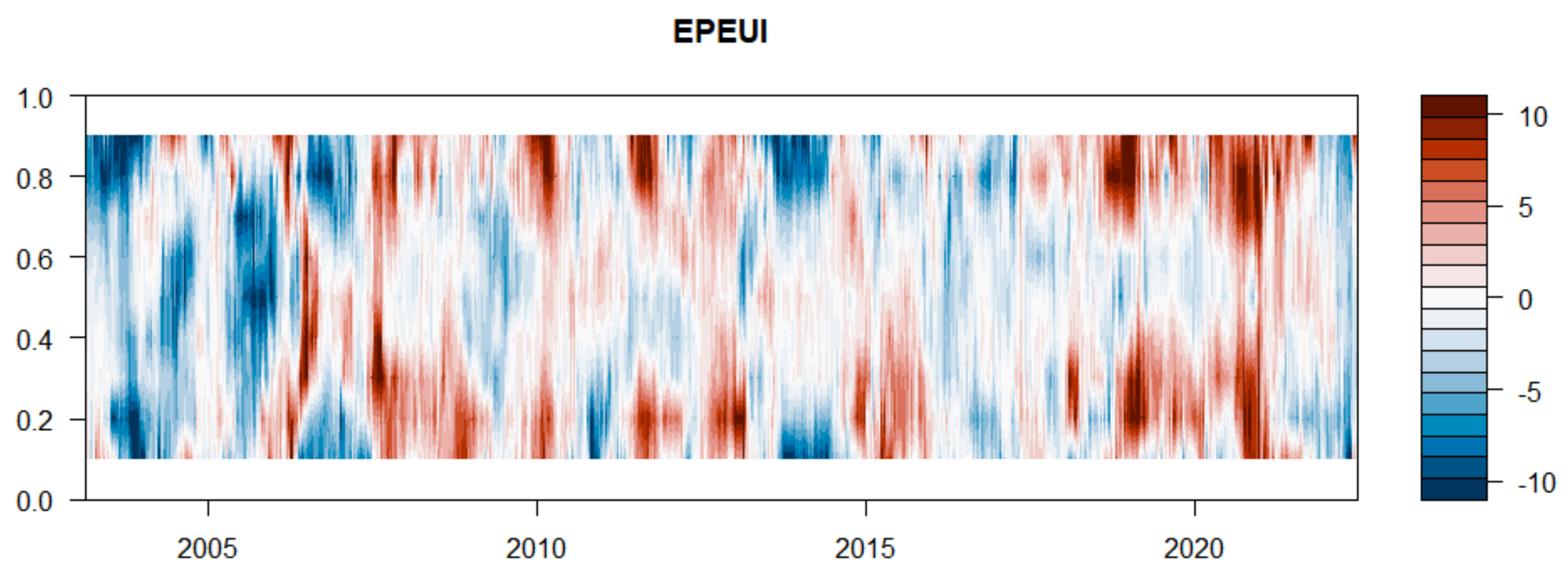

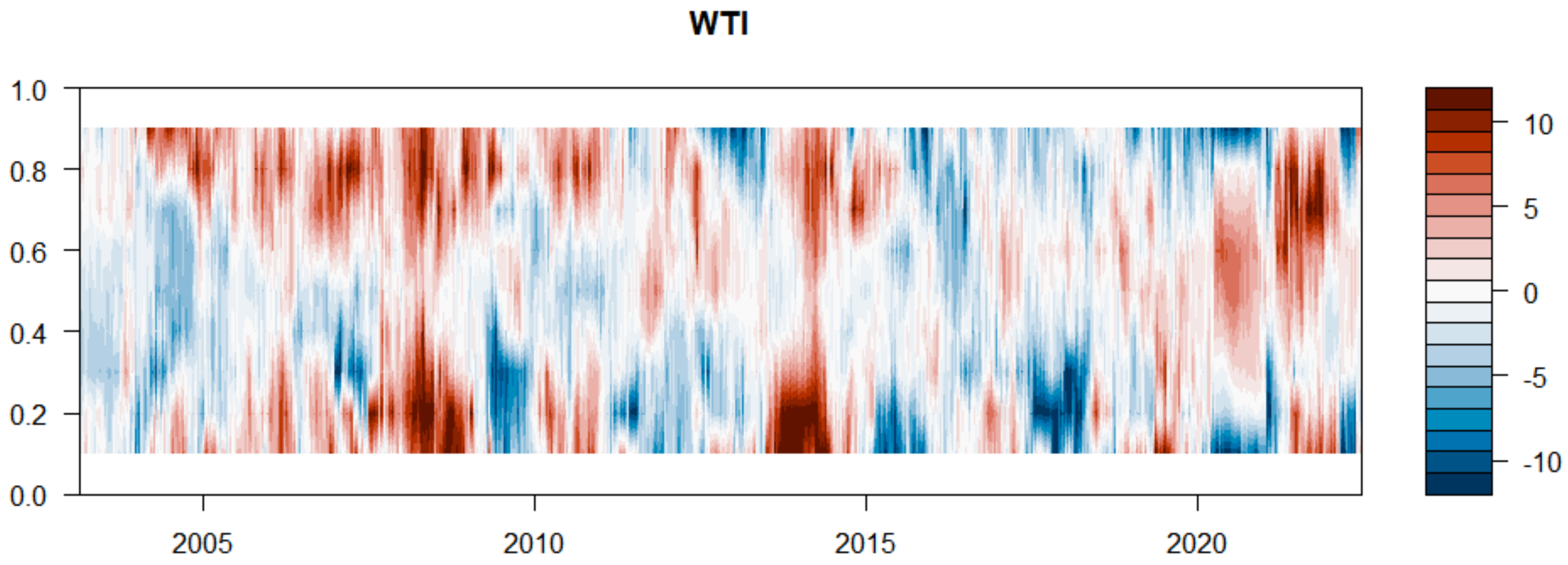

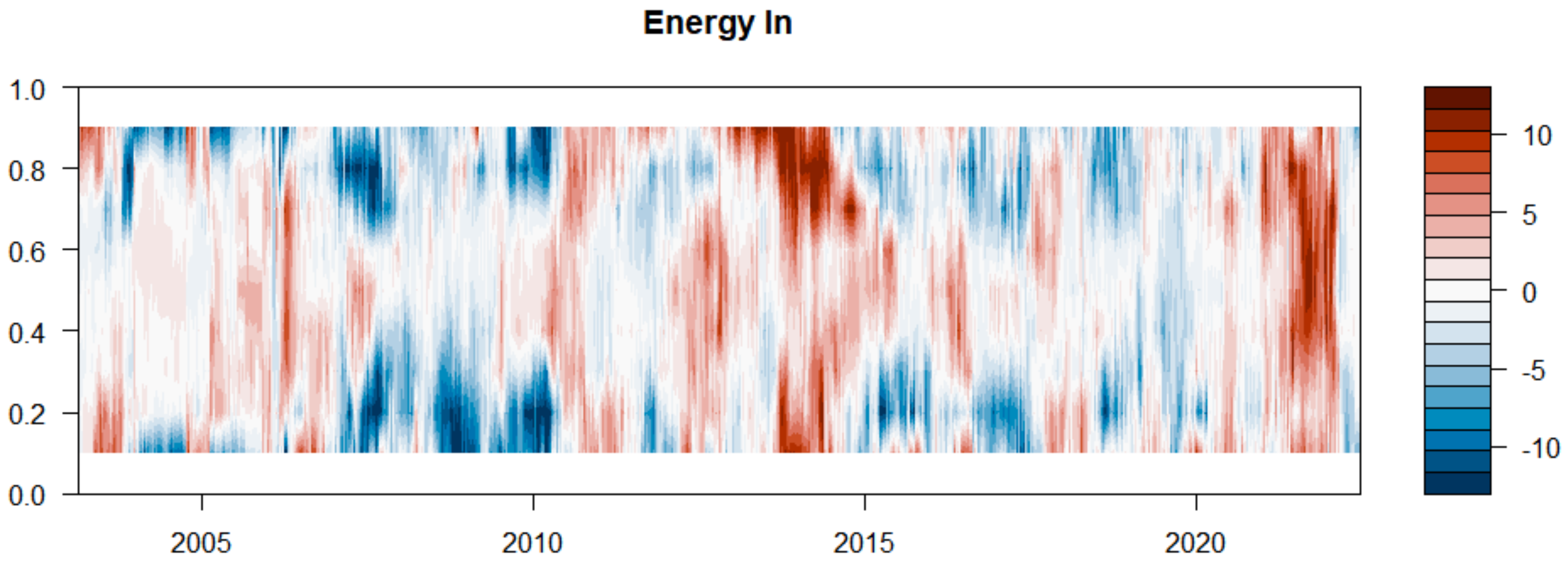

3.1. Data Description

3.2. Model Specification

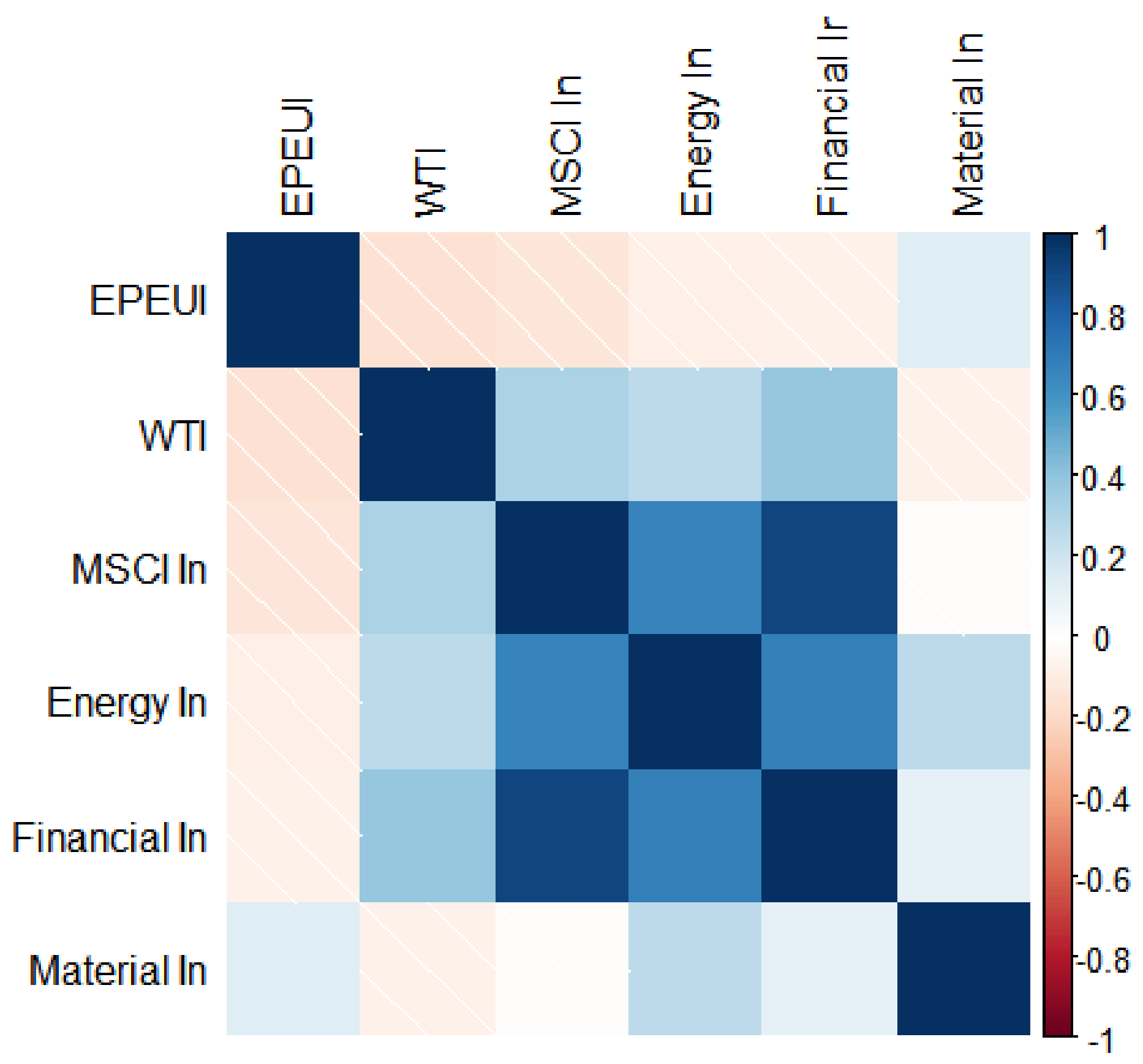

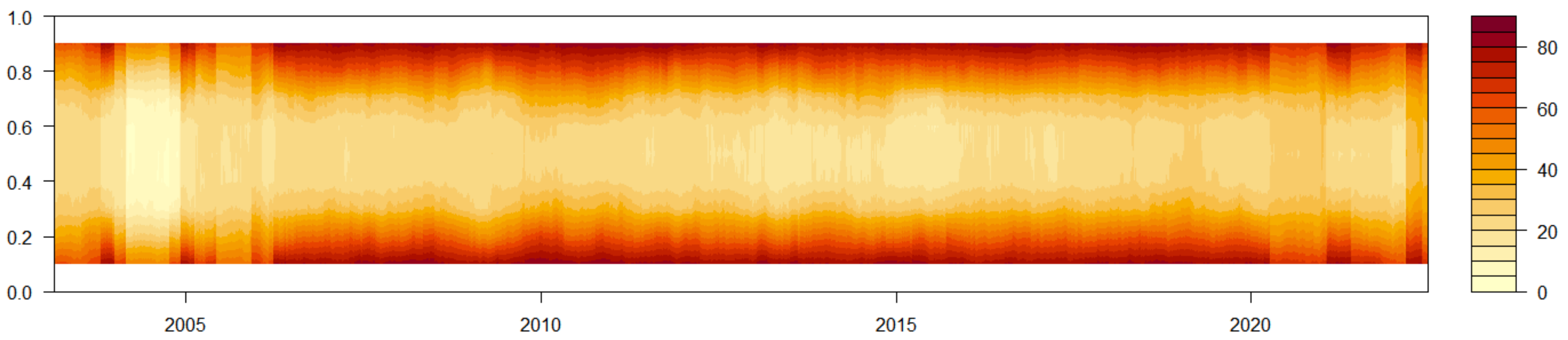

4. Result and Discussion

Static Quantile Connectedness

5. Conclusions

Limitation and Future Direction

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adam, N.; Sidek, N.Z.M.; Sharif, A. The Impact of Global Economic Policy Uncertainty and Volatility on Stock Markets: Evidence from Islamic Countries. Asian Econ. Financ. Rev. 2022, 12, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahiadorme, J.W. On the aggregate effects of global uncertainty: Evidence from an emerging economy. S. Afr. J. Econ. 2022, 90, 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D. The impacts of oil price shocks and United States economic uncertainty on global stock markets. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2022, 27, 1595–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, Q.R.; Bouri, E. Spillovers from global economic policy uncertainty and oil price volatility to the volatility of stock markets of oil importers and exporters. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 15603–15613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahir, H.; Bloom, N.; Furceri, D. The World Uncertainty Index; No. w29763; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.D.; Demirer, R. Oil beta uncertainty and global stock returns. Energy Econ. 2022, 112, 106150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ur Rehman, M.A. The impact of investor sentiment on returns, cash flows, discount rates, and performance. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2021, 22, 352–362. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, T. Economic policy uncertainty and stock market volatility. Financ. Res. Lett. 2015, 15, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fülöp, M.T.; Topor, D.I.; Ionescu, C.A.; Căpușneanu, S.; Breaz, T.O.; Stanescu, S.G. Fintech accounting and Industry 4.0: Futureproofing or threats to the accounting profession. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2022, 23, 997–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakhlaoui, I.; Aloui, C. The interactive relationship between the US economic policy uncertainty and BRIC stock markets. Int. Econ. 2016, 146, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, H.M.; Ullah, M.; Sohag, K.; Rehman, F.U. Considering the Impact of Sustainable Development Goals on Economic Boost-trip; A Case from Pakistan’s Economy. 2022. Available online: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1704495/v1 (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Stockhammar, P.; Österholm, P. The impact of US uncertainty shocks on small open economies. Open Econ. Rev. 2017, 28, 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, H.M.; Zatullah, M.; Li, Z. Effect of foreign direct investment on bilateral trade: Experience from asian emerging economies. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211054487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labidi, C.; Rahman, M.L.; Hedström, A.; Uddin, G.S.; Bekiros, S. Quantile dependence between developed and emerging stock markets aftermath of the global financial crisis. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2018, 59, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.E.; Soo-Wah, L.; Bilgili, F.; Ali, M.H. Connectedness and spillover effects of US climate policy uncertainty on energy stock, alternative energy stock, and carbon future. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghani, M.; Guo, Q.; Ma, F.; Li, T. Forecasting Pakistan stock market volatility: Evidence from economic variables and the uncertainty index. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2022, 80, 1180–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.L. Do economic policy uncertainty indices matter in joint volatility cycles between US and Japanese stock markets? Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 47, 102579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohag, K.; Gainetdinova, A.; Mariev, O. The response of exchange rates to economic policy uncertainty: Evidence from Russia. BorsaIstanb. Rev. 2022, 22, 534–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.P.; Schinckus, C.; Su, T.D. Asymmetric effects of global uncertainty: The socioeconomic and environmental vulnerability of developing countries. Fulbright Rev. Econ. Policy 2022, 2, 92–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.H.; Lee, C.M. International economic policy uncertainty and stock prices: Wavelet approach. Econ. Lett. 2015, 134, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamber, G.; Karagedikli, Ö.; Ryan, M. International Spillovers of Uncertainty Shocks: Evidence from a FAVAR; The Australian National University: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, T.G.; Bollerslev, T.; Diebold, F.X. Roughing it up: Including jump components in the measurement, modeling, and forecasting of return volatility. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2007, 89, 701–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Gomez, H.; Oltra-Badenes, R.; Guerola-Navarro, V.; ZegarraSaldaña, P. Crowdfunding: A bibliometric analysis. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzielinski, M. Measuring economic uncertainty and its impact on the stock market. Financ. Res. Lett. 2012, 9, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutchkova, M.; Doshi, H.; Durnev, A.; Molchanov, A. Precarious politics and return volatility. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2012, 25, 1111–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arouri, M.; Rault, C.; Teulon, F. Economic policy uncertainty, oil price shocks and GCC stock markets. Econ. Bull. 2014, 34, 1822–1834. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, T.; Chen, W.Y.; Gupta, R.; Nguyen, D.K. Are stock prices related to the political uncertainty index in OECD countries? Evidence from the bootstrap panel causality test. Econ. Syst. 2015, 39, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; de Gracia, F.P.; Ratti, R.A. Oil price shocks, policy uncertainty, and stock returns of oil and gas corporations. J. Int. Money Financ. 2017, 70, 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.E.; Zaidi, M.A.S. The impacts of global economic policy uncertainty on stock market returns in regime switching environment: Evidence from sectoral perspectives. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 24, 991–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepni, O.; Guney, I.E.; Swanson, N.R. Forecasting and nowcasting emerging market GDP growth rates: The role of latent global economic policy uncertainty and macroeconomic data surprise factors. J. Forecast. 2020, 39, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.J. An index of Global Economic Policy Uncertainty; No. w22740; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Antonakakis, N.; Chatziantoniou, I.; Filis, G. Oil shocks and stock markets: Dynamic connectedness under the prism of recent geopolitical and economic unrest. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2017, 50, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arouri, M.; Estay, C.; Rault, C.; Roubaud, D. Economic policy uncertainty and stock markets: Long-run evidence from the US. Financ. Res. Lett. 2016, 18, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, I.-C. The source of global stock market risk: A viewpoint of economic policy uncertainty. Econ. Model. 2017, 60, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Sharma, S.K. Testing output gap and economic uncertainty as an explicator of stock market returns. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2018, 45, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimic, N.; Kiviaho, J.; Piljak, V.; Äijö, J. Impact of financial market uncertainty and macroeconomic factors on stock-bond correlation in emerging markets. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2016, 36, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.E.; Zaidi, M.A.S. Global and country-specific geopolitical risk uncertainty and stock return of fragile emerging economies. BorsaIstanb. Rev. 2020, 20, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bams, D.; Blanchard, G.; Honarvar, I.; Lehnert, T. Does oil and gold price uncertainty matter for the stock market? J. Empir. Financ. 2017, 44, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Jiang, Z.-Q. The dynamic correlation between policy uncertainty and stock market returns in China. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2016, 461, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, A. The Spillover Effects of Global Economic Policy Uncertainty (GEPU) on Emerging Equity Markets: Evidence from Thailand. Doctoral Dissertation, NIDA, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.; Song, J. Volatility forecasting: Global economic policy uncertainty and regime switching. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2018, 511, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, F.X.; Yilmaz, K. Measuring financial asset return and volatility spillovers, with application to global equity markets. Econ. J. 2009, 119, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koop, G.; Korobilis, D.; Pettenuzzo, D. Bayesian compressed vector autoregressions. J. Econom. 2019, 210, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, T.; Greenwood-Nimmo, M.; Shin, Y. Quantile Connectedness: Modeling Tail Behavior in the Topology of Financial Networks. Manag. Sci. 2022, 68, 2401–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatziantoniou, I.; Gabauer, D.; Stenfors, A. Interest rate swaps and the transmission mechanism of monetary policy: A quantile connectedness approach. Econ. Lett. 2021, 204, 109891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koop, G.; Pesaran, M.H.; Potter, S.M. Impulse response analysis in nonlinear multivariate models. J. Econom. 1996, 74, 119–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, H.H.; Shin, Y. Generalized impulse response analysis in linear multivariate models. Econ. Lett. 1998, 58, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| EPEUI | WTI | MSCI | Energy | Financial | Material | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.692 | 0.59 | 0.416 | 0.422 | 0.607 | 0.479 |

| Variance | 0.521 | 0.652 | 0.827 | 0.822 | 0.632 | 0.771 |

| Skewness | 2.676 *** | 16.404 *** | 24.358 *** | 23.941 *** | 3.001 *** | 27.195 *** |

| Kurtosis | 11.636 *** | 515.686 *** | 778.546 *** | 750.828 *** | 12.532 *** | 1301.907 *** |

| JB | 341.01 *** | 556.70 *** | 126.89 *** | 117.99 *** | 402.75 *** | 353.42 *** |

| ERS | −15.107 *** | −19.849 *** | −21.512 *** | −21.275 *** | −10.859 *** | −19.895 *** |

| Q (10) | 935.348 *** | 1118.292 *** | 123.597 *** | 108.336 *** | 487.766 *** | 706.090 *** |

| Q (20) | 850.336 *** | 111.843 *** | 124.886 *** | 121.018 *** | 266.521 *** | 0.524 |

| EPEUI | WTI | MSCI | Energy | Financial | Material | FROM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPEUI | 91.34 | 1.79 | 0.9 | 1.65 | 2.77 | 1.55 | 8.66 |

| WTI | 1.69 | 87.6 | 1.71 | 2.23 | 3.36 | 3.41 | 12.4 |

| MSCI | 1.85 | 1.83 | 36.5 | 1.34 | 56.81 | 1.68 | 63.5 |

| Energy | 2.29 | 2.4 | 1.27 | 88.25 | 3.49 | 2.32 | 11.75 |

| Financial | 1.99 | 2.58 | 5.68 | 1.41 | 83.82 | 4.52 | 16.18 |

| Material | 1.34 | 3.12 | 1.25 | 1.84 | 4.35 | 88.11 | 11.89 |

| TO | 9.15 | 11.72 | 10.81 | 8.46 | 70.77 | 13.47 | 124.39 |

| Inc.Own | 100.49 | 99.32 | 47.31 | 96.71 | 154.59 | 101.58 | TCI |

| NET | 0.49 | −0.68 | −52.69 | −3.29 | 54.59 | 1.58 | |

| NPT | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 20.73 |

| EPEUI | WTI | MSCI | Energy | Financial | Material | FROM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPEUI | 54.86 | 9.53 | 9.59 | 8.84 | 8.57 | 8.61 | 45.14 |

| WTI | 9.37 | 52.63 | 9.97 | 9.5 | 9.3 | 9.23 | 47.37 |

| MSCI | 8.7 | 8.91 | 32.96 | 8.58 | 32.26 | 8.59 | 67.04 |

| Energy | 8.42 | 8.56 | 8.63 | 57.53 | 8.37 | 8.5 | 42.47 |

| Financial | 8.51 | 9.21 | 12.88 | 8.67 | 52 | 8.73 | 48 |

| Material | 8.31 | 8.53 | 8.82 | 8.54 | 8.31 | 57.5 | 42.5 |

| TO | 43.31 | 44.74 | 49.88 | 44.12 | 66.81 | 43.67 | 292.53 |

| Inc.Own | 98.17 | 97.36 | 82.84 | 101.65 | 118.8 | 101.17 | TCI |

| NET | −1.83 | −2.64 | −17.16 | 1.65 | 18.8 | 1.17 | 48.75 |

| NPT | 0 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| EPEUI | WTI | MSCI | Energy | Financial | Material | FROM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPEUI | 71.41 | 6.32 | 6.4 | 5.41 | 5.14 | 5.33 | 28.59 |

| WTI | 6.42 | 69.25 | 6.56 | 5.52 | 5.73 | 6.52 | 30.75 |

| MSCI | 4.61 | 4.93 | 33.05 | 5.12 | 46.45 | 5.83 | 66.95 |

| Energy | 5.17 | 5.05 | 4.78 | 74.49 | 5.29 | 5.22 | 25.51 |

| Financial | 5.01 | 5.51 | 8.77 | 5.21 | 69.75 | 5.75 | 30.25 |

| Material | 4.81 | 5.05 | 6.98 | 5.56 | 5.03 | 72.57 | 27.43 |

| TO | 26.03 | 26.86 | 33.48 | 26.82 | 67.64 | 28.65 | 209.48 |

| Inc.Own | 97.44 | 96.11 | 66.53 | 101.31 | 137.39 | 101.22 | TCI |

| NET | −2.56 | −3.89 | −33.47 | 1.31 | 37.39 | 1.22 | 34.91 |

| NPT | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| EPEUI | WTI | MSCI | Energy | Financial | Material | FROM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPEUI | 48.84 | 9.82 | 11.01 | 10.19 | 10.21 | 9.93 | 51.16 |

| WTI | 9.91 | 49.46 | 11.07 | 9.6 | 10.23 | 9.73 | 50.54 |

| MSCI | 7.92 | 8.76 | 27.55 | 9.11 | 37.37 | 9.3 | 72.45 |

| Energy | 9.45 | 9.39 | 9.93 | 52.2 | 9.82 | 9.22 | 47.8 |

| Financial | 8.37 | 9.59 | 13.78 | 10.2 | 47.72 | 10.35 | 52.28 |

| Material | 9.09 | 9.14 | 11.03 | 10.62 | 9.46 | 50.66 | 49.34 |

| TO | 44.74 | 46.7 | 56.81 | 49.72 | 77.09 | 48.53 | 323.58 |

| Inc.Own | 93.57 | 96.15 | 84.36 | 101.91 | 124.8 | 99.19 | TCI |

| NET | −6.43 | −3.85 | −15.64 | 1.91 | 24.8 | −0.81 | 53.93 |

| NPT | 1 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khan, S.; Ullah, M.; Shahzad, M.R.; Khan, U.A.; Khan, U.; Eldin, S.M.; Alotaibi, A.M. Spillover Connectedness among Global Uncertainties and Sectorial Indices of Pakistan: Evidence from Quantile Connectedness Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15908. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315908

Khan S, Ullah M, Shahzad MR, Khan UA, Khan U, Eldin SM, Alotaibi AM. Spillover Connectedness among Global Uncertainties and Sectorial Indices of Pakistan: Evidence from Quantile Connectedness Approach. Sustainability. 2022; 14(23):15908. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315908

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhan, Shabeer, Mirzat Ullah, Mohammad Rahim Shahzad, Uzair Abdullah Khan, Umair Khan, Sayed M. Eldin, and Abeer M. Alotaibi. 2022. "Spillover Connectedness among Global Uncertainties and Sectorial Indices of Pakistan: Evidence from Quantile Connectedness Approach" Sustainability 14, no. 23: 15908. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315908

APA StyleKhan, S., Ullah, M., Shahzad, M. R., Khan, U. A., Khan, U., Eldin, S. M., & Alotaibi, A. M. (2022). Spillover Connectedness among Global Uncertainties and Sectorial Indices of Pakistan: Evidence from Quantile Connectedness Approach. Sustainability, 14(23), 15908. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315908