Social Reporting in Healthcare Sector: The Case of Italian Public Hospitals

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- -

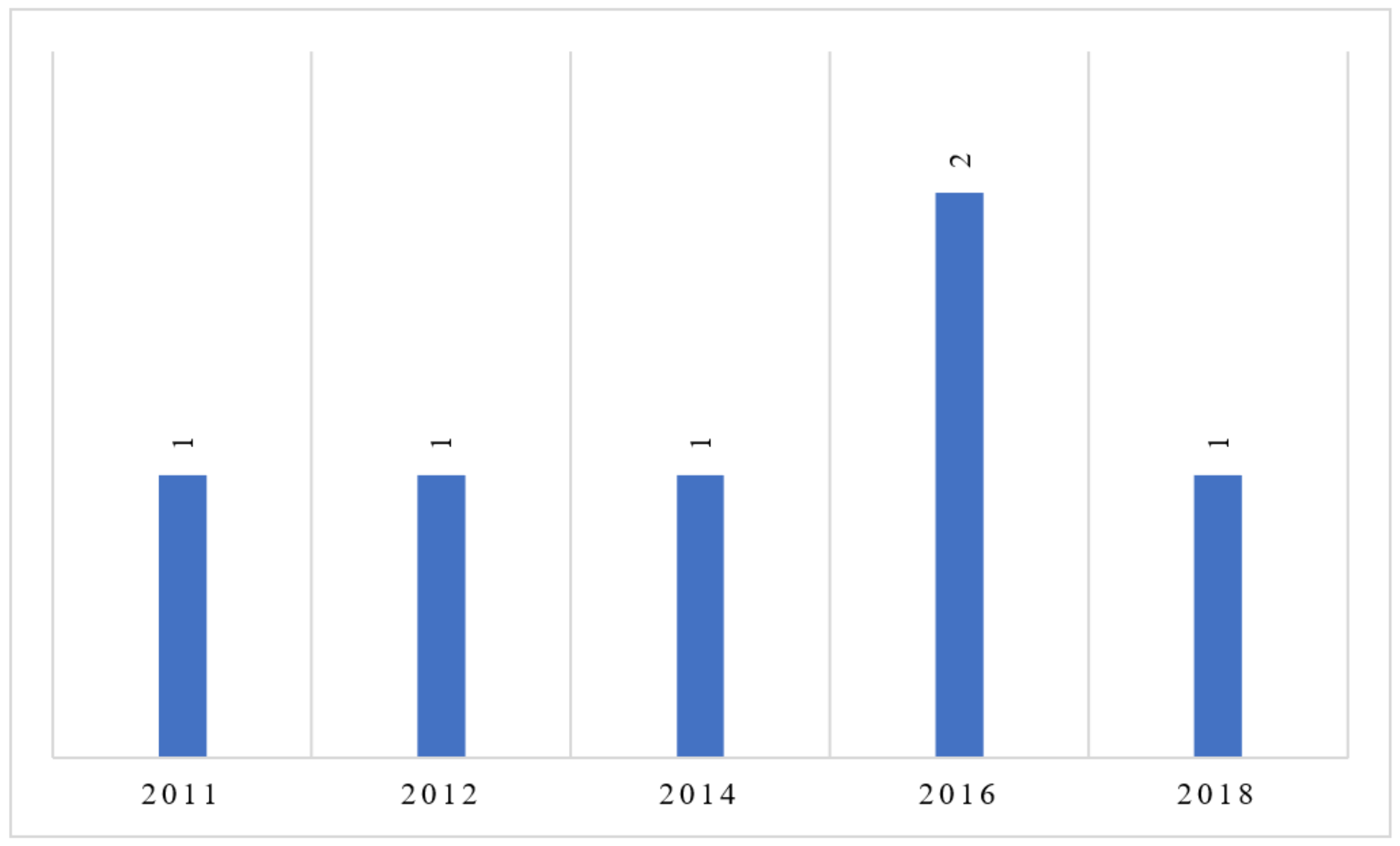

- The existence of a slow trend of social reporting initiatives;

- -

- A lack of homogeneity in SRs of AOs (in terms of structure, content, methods of dissemination of documents, etc.).

- (1)

- To assess the trends of social reporting initiatives in the Italian public hospital sector;

- (2)

- To analyze the current forms, contents, and quality of social reporting documents, in order to isolate common elements, differentiation, and emerging trends;

- (3)

- To analyze the informational power of social reporting documents for public AOs’ stakeholders, describing their information needs and comparing these with information deduced from reading the document.

The Italian National Health System

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Method and Selection Criteria

2.2. Document Analysis Criteria

- -

- The standards proposed by the Italian study group for the SR (Gruppo di studio per il bilancio sociale (GBS)) published since 2001 (with specific reference to the public sector) [32];

- -

- The guidelines on social reporting for public administrations, drawn up in 2006 by the Department of Public Administration [33].

- (a)

- The publication, “preferably” on an annual basis, of the documents;

- (b)

- The presence of minimal information content. Table 2 shows the description of the information required according to the two standards.

3. Results

3.1. Social Reporting in Italian Public Hospitals: State of the Art

3.2. Structure, Content, and Quality of Documents

- -

- Institutional structure and AO organizational system (departments and their functions);

- -

- Principles and reference values;

- -

- Strategies and policies implemented;

- -

- Guidelines, objectives, and future strategies.

- -

- Composition and roles of internal human resources (employees);

- -

- providers;

- -

- Patients, users, and level of satisfaction.

- -

- Available technological resources (Technologies and innovation—Section 7);

- -

- Resources used to carry out hospital activities, investments, and purchases (Economic report—Section 8);

- -

- Information about the out-of-court and judicial management system, or the assignment of legal appointments, liquidation, and risk assessment systems (Litigation—Section 9);

- -

- Quality management system, i.e., assistance paths created for the adaptation of the various professional skills to the production of effective and appropriate assistance, as well as centered on the patients’ needs and on the continuous improvement of quality (quality and accreditation—Section 10);

- -

- Hospital information system, or description of the network infrastructure available to the hospital, to allow patients and employees to use the information and online services (Section 11);

- -

- Performance plan or strategic and operational guidelines and objectives defined, and indicators for their measurement and evaluation. Finally, description of the transparency and corruption plan (Performance, transparency, and corruption prevention—Section 12);

- -

- Description of the health objectives and services targets defined by the region (Regional objectives—Section 13).

3.3. Informational Power of SR for Public Hospital Stakeholders

- -

- The role of the hospital with respect to the achievement of the objectives of the entire regional health system;

- -

- The level of efficiency, effectiveness, and overall cost-effectiveness;

- -

- The implementation of projects for improvement, innovation, and requalification of assistance models.

4. Discussion, Limitations, and Conclusions

- -

- The Accountability 1000 (AA1000) [35];

- -

- The GRI [36];

- -

- The standards proposed by the Copenhagen Charter [37];

- -

- At the national level, the standards proposed by the Italian study group for the SR (GBS) published since 2001 (with specific reference to the public sector) [32];

- -

- The guidelines on social reporting for public administrations, drawn up in 2006 by the Department of Public Administration [33].

- -

- This has led to divergences in the documents, as the healthcare structures prepare their SRs referring to different standards, or in some cases referring to multiple standards at once.

- (a)

- To acquire information about the documents being processed or completed;

- (b)

- To understand any difficulties or barriers in social reporting documents development, also in light of the lack of specific guidelines for hospitals;

- (c)

- To develop a basic reference model to support the process of preparing social reporting documents for AOs, which takes into account the specific characteristics of this type of structure.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fonseca, A.; Macdonald, A.; Dandy, E.; Valenti, P. The state of sustainability reporting at Canadian universities. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2011, 12, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.; Zutshi, A. Corporate social responsibility: Why business should act responsibly and be accountable. Aust. Account. Rev. 2004, 14, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.C. Corporate social responsibility: Whether or how? Calif. Manag. Rev. 2003, 45, 52–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU Commission. Communication from the Commission Concerning Corporate Social Responsibility: A Business Contribution to Sustainable Development 5 (COM(2002) 347 Final, Brussels, 2 July 2002). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2002:0347:FIN:en:pdf (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Crowther, D.; Aras, G. Corporate Social Responsibility; Bookboon: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jennifer Ho, L.C.; Taylor, M.E. An empirical analysis of triple bottom-line reporting and its determinants: Evidence from the United States and Japan. J. Int. Financ. Manag. Account. 2007, 18, 123–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetherington, J.A.C. Corporate Social Responsibility Audit: A Management Tool for Survival; The Foundation for Business Responsibilities: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, R.A. A prelude to corporate reform. Bus. Soc. Rev. 1972, 1, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K. The Case for and against Business Assumption of Social Responsibilities. Acad. Manag. J. 1973, 16, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B.; Shabana, K.M. The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romolini, A. Accountability E Bilancio Sociale Negli Enti Locali; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Van Marrewijk, M. Concepts and definitions of CSR and corporate sustainability: Between agency and communion. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Enter the Triple Bottom Line. In The Triple Bottom Line: Does It All Add up, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, H.S.; De Jong, M.; Levy, D.L. Building institutions based on information disclosure: Lessons from GRI’s sustainability reporting. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcuccio, M. La rendicontazione sociale per le amministrazioni locali come strumento di accountability e controllo strategico. Azienda Pubblica 2002, 6, 637–672. [Google Scholar]

- Meneguzzo, M. Innovazione, Managerialità E Governance. In La PA Verso Il 2000; Aracne: Roma, Italy, 2001; pp. 1–426. [Google Scholar]

- Secchi, D. The Italian experience in social reporting: An empirical analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2006, 13, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albareda, L.; Lozano, J.M.; Ysa, T. Public policies on corporate social responsibility: The role of governments in Europe. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 74, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J.; Manes-Rossi, F.; Orelli, R.L. Integrated reporting and integrated thinking in Italian public sector organisations. Meditari Account. Res. 2017, 25, 553–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macuda, M.; Toledo, M.A.R. The scope of environmental disclosure in the European healthcare sector–an empirical study. Zesz. Teor. Rachun. 2020, 110, 105–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.; Svensson, G.; Wood, G. Sustainability trends in public hospitals: Efforts and priorities. Eval. Program Plan. 2020, 78, 101742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesani, D.; Marcuccio, M.; Trinchero, E. Bilancio sociale e aziende sanitarie: Stato dell’arte e prospettive di sviluppo. Mecosan 2005, 55, 9–34. [Google Scholar]

- Alesani, D.; Cantu, E.; Marcuccio, M.; Trinchero, E. La Rendicontazione Sociale Nelle Aziende Sanitarie: Funzionalità E Potenzialità. In Rapporto Oasi; Egea: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 617–663. [Google Scholar]

- Del Vecchio, M.; De Pietro, C. Italian public health care organizations: Specialization, institutional deintegration, and public networks relationships. Int. J. Health Serv. 2011, 41, 757–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, M.; Giancotti, M. Italian responses to the COVID-19 emergency: Overthrowing 30 years of health reforms? Health Policy 2021, 125, 548–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrè, F.; Cuccurullo, C.; Lega, F. The challenge and the future of health care turnaround plans: Evidence from the Italian experience. Health Policy 2012, 106, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Belvis, A.G.; Ferrè, F.; Specchia, M.L.; Valerio, L.; Fattore, G.; Ricciardi, W. The financial crisis in Italy: Implications for the healthcare sector. Health Policy 2012, 106, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, G.A. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Book review: Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks CA Sage. Organ. Res. Methods 2008, 12, 614–617. [Google Scholar]

- Rapley, T. Doing Conversation, Discourse and Document Analysis; Sage: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- GBS Gruppo Di Studio Per Il Bilancio Sociale. Available online: http://www.gruppobilanciosociale.org/ (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Dipartimento Della Funzione Pubblica. Direttiva 17 Febbraio 2006. In Rendicontazione Sociale Nelle Amministrazioni Pubbliche (Gazzetta Ufficiale Serie Generale n.63 del 16-03-2006); Dipartimento Della Funzione Pubblica: Roma, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hinna, L. Il Bilancio Sociale Nelle Amministrazioni Pubbliche. In Processi, Strumenti, Strutture E Valenze; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2008; pp. 1–272. [Google Scholar]

- Beckett, R.; Jonker, J. Accountability 1000: A new social standard for building sustainability. Manag. Audit. J. 2002, 17, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilburn, K.; Wilburn, R. Using global reporting initiative indicators for CSR programs. J. Glob. Responsib. 2013, 4, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Copenhagen Charter. A Management Guide to Stakeholder Reporting. 1999. Available online: http://base.socioeco.org/docs/doc-822_en.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- La Rendicontazione Sociale Delle Aziende Sanitarie. Available online: http://www.gruppobilanciosociale.org/pubblicazioni/la-rendicontazione-sociale-delle-aziende-sanitarie-documenti-di-ricerca-n-9/ (accessed on 2 April 2022).

| REGION | N AO | N AOU | N ASL | N IRCCS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piemonte | 3 | 3 | 12 | - |

| Valle D’Aosta | - | - | 1 | - |

| Lombardia | 27 | - | 8 | 5 |

| Veneto | 1 | 1 | 9 | 1 |

| Prov. Autonoma Bolzano | - | - | 1 | - |

| Prov. Autonoma Trento | - | - | 1 | - |

| Friuli Venezia Giulia | - | - | 5 | 2 |

| Liguria | - | - | 5 | 2 |

| Emilia Romagna | - | 4 | 8 | 2 |

| Toscana | - | 4 | 3 | - |

| Umbria | 2 | - | 2 | - |

| Marche | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Lazio | 2 | 3 | 10 | 2 |

| Abruzzo | - | - | 4 | - |

| Molise | - | - | 1 | - |

| Campania | 6 | 3 | 7 | 1 |

| Puglia | - | 2 | 6 | 2 |

| Basilicata | 1 | - | 2 | 1 |

| Calabria | 4 | - | 5 | 1 |

| Sicilia | 5 | 3 | 9 | 2 |

| Sardegna | 1 | 2 | 1 | - |

| Total | 53 | 26 | 101 | 22 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| N. SR 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. of pages | 57 | 84 | 49 | 76 | 100 | 105 |

| N. of figures | 12 | 100 | 40 | 46 | 57 | 0 |

| N. of graphs | 5 | 44 | 28 | 32 | 45 | 55 |

| Section 1 | Public hospital identity | Context and organizational structure | Context | Public hospital identity | Public hospital and the three-year objectives | Public hospital presentation |

| Section 2 | Economic report | Activity of the year | From analysis to strategy | Economic report and activity | Public hospital identity | Patient reports |

| Section 3 | Social relationship | The gender perspective and equal opportunities | Results | Social relationship | Balance sheet and economic report | Communication |

| Section 4 | Improvement objectives | Human resources | Projects and results (achieved during the year) | The evolution of activities and services | The numbers of public hospital | |

| Section 5 | Social relationship | Outcome | Social reporting | Gender balance | ||

| Section 6 | The performance plan | Staff and training | ||||

| Section 7 | Technologies and innovation | |||||

| Section 8 | Economic report | |||||

| Section 9 | The litigation | |||||

| Section 10 | Quality and accreditation | |||||

| Section 11 | The hospital information system | |||||

| Section 12 | Performance, transparency and corruption | |||||

| Section 13 | Regional objectives | |||||

| Appendix | Appendix I | Appendix 1 | ||||

| Appendix 2 | ||||||

| Appendix 3 |

| Required Information Content (GBS and Department of Public Administration Standards) | SR1 | SR2 | SR3 | SR4 | SR5 | SR6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Institutional setting | X (Public hospital identity—Section 1) | X (Context and organizational structure—Section 1) | X (Context—Section 1) | X (Public hospital identity—Section 1) | X (Public hospital identity—Section 2) | X (Public hospital identity—Section 1) |

| 2. Reference value | X (Public hospital identity—Section 1) | X (Context and organizational structure—Section 1) | X (Context—Section 1) | X (Public hospital identity—Section 1) | X (Public hospital identity—Section 2) | X (Public hospital identity—Section 1) |

| 3. Resources used and investments | X (Economic report—Section 2) | X (Activity of the year—Section 2) | X (From analysis to strategy—Section 2) | X (Economic report and Activity—Section 2) | X (Balance sheet and economic report—Section 3) | X (Economic report—Section 8) |

| 4. Activities and services | X (Economic report—Section 2) | X (Activity of the year—Section 2) | X (Results—Section 3; Project and Results—Section 4) | X (Economic report and Activity—Section 2) | X (The evolution of activities and services—Section 4) | X (The numbers of public hospital—Section 4) |

| 5. Social reporting data | X (Social relationship—Section 3) | X (The gender perspective and equal opportunities—Section 3; Human resources—Section 4; Social relationship—Section 5) | X (Outcome—Section 5) | X (Social relationship—Section 3) | X (Social reporting—Section 5) | X (Patient report—Section 2; communication—Section 3, Gender balance—Section 5) |

| 6. Future commitments, actions and improvement objectives | X (Improvement objectives—Section 4) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 7. Supplementary information | X (Section Appendix) | X (Section Appendix) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giancotti, M.; Ciconte, V.; Mauro, M. Social Reporting in Healthcare Sector: The Case of Italian Public Hospitals. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15940. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315940

Giancotti M, Ciconte V, Mauro M. Social Reporting in Healthcare Sector: The Case of Italian Public Hospitals. Sustainability. 2022; 14(23):15940. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315940

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiancotti, Monica, Valeria Ciconte, and Marianna Mauro. 2022. "Social Reporting in Healthcare Sector: The Case of Italian Public Hospitals" Sustainability 14, no. 23: 15940. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315940

APA StyleGiancotti, M., Ciconte, V., & Mauro, M. (2022). Social Reporting in Healthcare Sector: The Case of Italian Public Hospitals. Sustainability, 14(23), 15940. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315940