Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Pro-Poor Tourism Villages in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

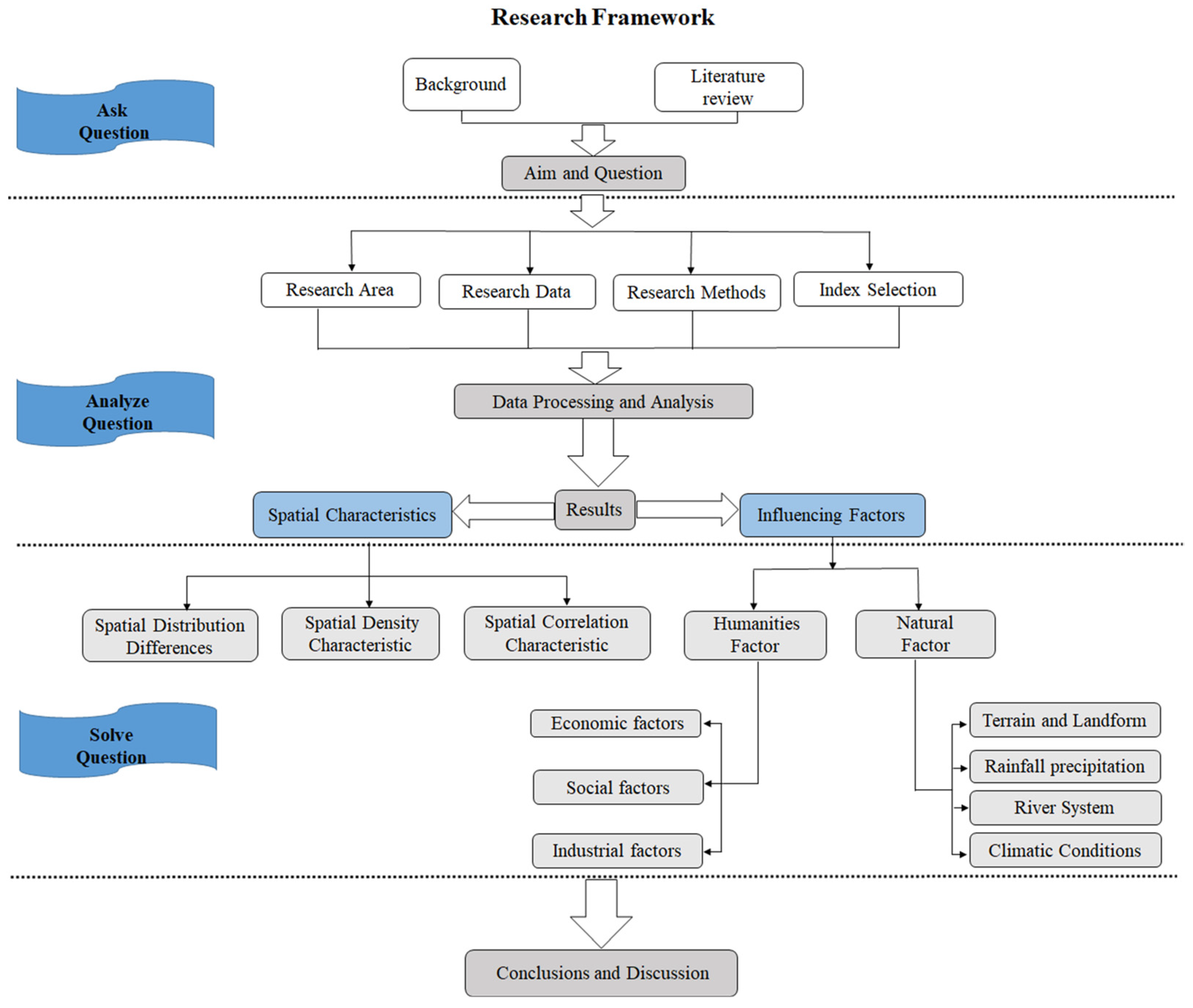

3. Study Methods and Data Sources

3.1. Study Methods

3.1.1. Nearest Neighbor Index

3.1.2. Disequilibrium Index

3.1.3. Spatial Correlation Analysis

3.1.4. Geographical Detector

3.1.5. Overlay Analysis

3.2. Data Sources and Indicator Selection

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of Spatial Distribution Differences

4.1.1. Overall Difference

4.1.2. Regional Differences

4.1.3. Provincial Differences

4.2. Spatial Density Characteristic

4.3. Spatial Correlation Feature

5. Factors Influencing the Spatial Distribution of Pro-Poor Tourism Villages

5.1. Humanities Factor Detection Analysis

5.1.1. Economic Factors

5.1.2. Social Factors

5.1.3. Industrial Factors

5.2. Natural Factor Detection Analysis

5.2.1. Terrain and Landform

5.2.2. Rainfall Precipitation

5.2.3. River System

5.2.4. Climatic Conditions

6. Discussion

6.1. Study of Spatial Distribution Characteristics to Help Optimize the Spatial Layout of Pro-Poor Tourism Villages

6.2. The Study of Influencing Factors Provides New Ideas for Implementing Rural Revitalization Strategies in Pro-Poor Tourism Villages

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Prospects

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- Based on GIS spatial analysis technologies, this paper systematically analyzes the spatial distribution characteristics of the first and second batches of pro-poor tourism villages by using the methods of the nearest proximity index, disequilibrium index, kernel density analysis, and spatial autocorrelation. On this basis, an index system of influencing factors is constructed from the two aspects of human and natural factors. In addition, geographic detector and superposition analyses are used to conduct quantitative geospatial detection and analysis of the factors affecting the spatial distribution of pro-poor tourism villages. The following main conclusions were drawn. The overall spatial distribution pattern shows a “large concentration and small dispersion” pattern. Regarding spatial agglomeration, the spatial pattern is characterized by clusters in the western region and supplemented by strips in the central region. East of the Hu Huanyong population line, there are 4257 pro-poor tourism villages, accounting for 73.8% of the country, while west of the Hu Huanyong population line, there are 1513 pro-poor tourism villages, accounting for only 26.2%. This shows that the difference in the number and density of east and west pro-poor tourism villages are significant and have apparent characteristics such as longitudinal geographical differentiation.

- (2)

- The regional distribution of pro-poor tourism villages is extremely uneven across three major zones, eight regions, and at the inter-provincial level. The proportion of pro-poor tourism villages in central and western regions was 93.4%, while that in eastern regions was only 6.6%. The spatial disequilibrium index of the pro-poor tourism villages in the eight regions was 0.56, indicating that the pro-poor tourism villages were disequilibrium in the eight regions, mainly concentrated in the southwest region, the northwest region, the middle reaches of the Yellow River, and the middle reaches of the Yangtze River, accounting for 89.5%. The spatial disequilibrium index of provincial pro-poor tourism villages was 0.54, mainly distributed in Yunnan, Guizhou, Gansu, Shaanxi, Sichuan, Hebei, and Hunan provinces, with a small number in Ningxia, Jilin, and Hainan provinces.

- (3)

- In terms of the overall density, pro-poor tourism villages show a distribution trend of “one belt with five cores gathering in the mountainous area”, forming a high-density agglomeration belt connecting Hebei–Henan–Anhui–Hubei; five massive high-density clustering cores in southern Gansu; the border area of Sichuan, Gansu, and Shaanxi; the border area of Guizhou, Hunan, and Chongqing; southern Sichuan; and southwest Guizhou. The “One Belt, Five Cores” high-density area shows clustering around the Yanshan–Taihang Mountains, Qilian–Qinling–Hengduan Mountains, and the Wushan–Xuefeng Mountains.

- (4)

- In terms of spatial association, the spatial distribution of both groups of pro-poor tourism villages shows a more significant spatial autocorrelation. In general, pro-poor tourism villages are spatially clustered, with hot spots clustered in the Loess Plateau, Sichuan, and Chongqing regions and the Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau, and cold spots clustered in the northeast and east coast of China in a striped distribution, showing a hot spatial distribution pattern of in the central and western areas and cold distributions in the east coast. The hot spot areas are slowly increasing, and the cold spot areas are gradually decreasing. The trend of clustering pro-poor tourism villages is becoming increasingly obvious, and the spatial characteristics of hot and cold patterns are becoming increasingly stable.

- (5)

- Regarding influencing factors, pro-poor tourism villages are influenced by human factors such as social, economic, and industrial factors and natural geographical factors such as topography, precipitation, rivers, and climate. The intensity of the humanities level indicator factor on the distribution of regional pro-poor tourism villages shows industrial factors (0.41) > economic factors (0.35) > social factors (0.16). The five factors of secondary indicator factors, namely gross regional product, GDP per capita, domestic tourism income, the number of scenic spots above grade 4A, and the number of guest houses and lodges, have a more obvious influence on the distribution of pro-poor tourism villages. The natural distribution of pro-poor tourism villages tends to be humid mountainous areas with an altitude of about 1000 m and an annual precipitation of more than 800 mm, and it is mostly distributed in the subtropical monsoon climate zones close to rivers with more suitable climates.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, Y.; Guo, L.; Liu, Y. Land consolidation boosting poverty alleviation in China: Theory and practice. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Y. The code of targeted poverty alleviation in China: A geography perspective. Geogr. Sustain. 2021, 2, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geall, S.; Shen, W. Solar energy for poverty alleviation in China: State ambitions, bureaucratic interests, and local realities. Energy. Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 41, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y. Spatio-temporal patterns of rural poverty in China and targeted poverty alleviation strategies. J. Rural. Stud. 2017, 52, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.; Xu, H.; Chung, Y. Perceived impacts of the poverty alleviation tourism policy on the poor in China. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 41, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R.; Russell, M. Tourism and poverty alleviation in Fiji: Comparing the impacts of small-and large-scale tourism enterprises. J. Sustain.Tour. 2012, 20, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, C.; Roe, D. Making tourism work for the poor: Strategies and challenges in southern Africa. Dev. S. Afr. 2002, 19, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Muñoz, D.R.; Gutiérrez-Pérez, F.J. The impacts of tourism on poverty alleviation: An integrated research framework. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 270–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, P.; Corral, L.; Mora, A.M. Assessing the role of tourism in poverty alleviation: A research agenda. Dev. Policy Rev. 2013, 31, 177–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, L.; Sahli, M. Foreign direct investment in tourism, poverty alleviation, and sustainable development: A review of the Gambian hotel sector. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, W. Cultural tourism and poverty alleviation in rural Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2015, 13, 208–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Wang, X.; Ryan, C. Chinese seniors holidaying, elderly care, rural tourism and rural poverty alleviation programmes. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekawy, M.A. Smart tourism investment: Planning pathways to break the poverty cycle. Tour. Rew. Int. 2015, 18, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novelli, M.; Hellwig, A. The UN Millennium Development Goals, tourism and development: The tour operators’ perspective. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J.; Ashley, C. Tourism and Poverty Reduction: Pathways to Prosperity; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zha, J.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; He, L.; Shu, H. What caused the wage changes in tourism-related industries? A demand-side analysis based on an extended input-output model. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlenbrook, S.; Yu, W.; Schmitter, P.; Smith, D.M. Optimising the water we eat—Rethinking policy to enhance productive and sustainable use of water in agri-food systems across scales. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.M.; Wall, G.; Wang, Y.; Jin, M. Livelihood sustainability in a rural tourism destination-Hetu Town, Anhui Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocca, F.; Girard, L.F. Towards an integrated evaluation approach for cultural urban landscape conservation/regeneration. Region 2018, 5, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carraresi, L.; Bröring, S. How does business model redesign foster resilience in emerging circular value chains? J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 289, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravallion, M.; Chen, S. Is that really a Kuznets curve? Turning points for income inequality in China. J. Econ. Inequal. 2022, 14, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, T.; Kim, S. Exploring the relationship between tourism and poverty using the capability approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1655–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Xu, H.; Cui, Q. Tourism and poverty alleviation in Tibet, China: The role of government in enhancing local linkages. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 27, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, H. Reflections on 10 years of pro-poor tourism. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2009, 1, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chok, S.; Macbeth, J.; Warren, C. Tourism as a tool for poverty alleviation: A critical analysis of ‘pro-poor tourism’ and implications for sustainability. Curr. Issues Tour. 2007, 10, 144–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luvanga, N.; Shitundu, J. The role of tourism in poverty alleviation in Tanzania. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 12, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, V.D.; Hall, C.M.; Garry, T. Tourism and poverty alleviation: Perceptions and experiences of poor people in Sapa, Vietnam. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 1071–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L. Tourism, institutions, and poverty alleviation: Empirical evidence from China. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 1543–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, S. Spatial analysis of public health facilities in Riyadh Governorate, Saudi Arabia: A GIS-based study to assess geographic variations of service provision and accessibility. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2016, 19, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Peng, B.; Elahi, E. Spatial and temporal pattern evolution and influencing factors of energy–environmental efficiency: A case study of yangtze river urban agglomeration in China. Energy Environ. 2021, 32, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, C. Geodetector: Principle and prospective. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 116–134. [Google Scholar]

- Sokal, R.R.; Oden, N.L. Spatial autocorrelation in biology: 1. Methodology. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 1978, 10, 199–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, M. Spatial distribution pattern and influencing factors of sports tourism resources in China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama, K.; Hayashi, H. Strigolactones: Chemical signals for fungal symbionts and parasitic weeds in plant roots. Ann. Bot. 2006, 97, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Yan, H.; Liu, F.; Du, W.; Yang, Y. Multiple global population datasets: Differences and spatial distribution characteristics. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, W.; Huang, W. Rediscussing the Political Struggle in the Light of Reform in Late 11th Century China under the View of Digital Humanities. Digit. Humanit. Q. 2022, 16, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Luo, J.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, L.; Tian, L.; Chen, G. Characteristics and influencing factors of spatial differentiation of urban black and odorous waters in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, J.; Jiang, L.; Luo, J.; Tian, L.; Tian, Y.; Chen, G. Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Spatial Differentiation of Market Service Industries in Rural Areas around Metropolises—A Case Study of Wuhan City’s New Urban Districts. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, L.L.; Yu, D.; Zhang, J.; Liu, F.F.; Wu, Y.H.; Zhang, T.Y.; Hu, H.Y. The characteristics and influencing factors of the attached microalgae cultivation: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energ. Rev. 2018, 94, 1110–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, C.M.; Saarinen, J. Tourism for poverty alleviation: Issues and debates in the global South. SAGE Handb. Tour. Manag. Appl. Theor. Concepts Tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 12, 22–37. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Z.; Bao, J. Targeted poverty alleviation in China: Segmenting small tourism entrepreneurs and effectively supporting them. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1984–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, C.; Wu, J.; Liang, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Nazneen, S. Human poverty alleviation through rural women’s tourism entrepreneurship. J. China Tour. Res. 2018, 14, 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, N.; Wei, F.; Zhang, K.H.; Gu, D. Innovating rural tourism targeting poverty alleviation through a multi-Industries integration network: The case of Zhuanshui village, Anhui province, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primary Influencing Factors | q-Value | Secondary Influencing Factors | Unit | q-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic factors | 0.35 | Urbanization rate | percent | 0.31 |

| Gross regional product | Chinese CNY | 0.43 | ||

| GDP per capita | Chinese CNY | 0.43 | ||

| Per capita disposable income of rural residents | Chinese CNY | 0.28 | ||

| Social factors | 0.16 | Size of population | person | 0.22 |

| Educational attainment (preschool) | person | 0.14 | ||

| Educational attainment (elementary school) | person | 0.28 | ||

| Educational attainment (high school) | person | 0.21 | ||

| Number of beds per 1000 people | / | 0.38 | ||

| Number of doctors per thousand | / | 0.14 | ||

| Integrated density of railroad network | km·10,000 km−2 | 0.38 | ||

| Integrated density of highway network | km·10,000 people−1 | 0.30 | ||

| Industrial factors | 0.41 | Domestic tourism revenue | Chinese CNY | 0.45 |

| Number of tourist receivers | / | 0.24 | ||

| Number of scenic spots above grade 4A | / | 0.40 | ||

| Number of travel agencies | / | 0.03 | ||

| Number of star-rated hotels | / | 0.22 | ||

| Number of inns and lodges | / | 0.63 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, L.; Hu, J.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Liang, M. Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Pro-Poor Tourism Villages in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15953. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315953

Zhu L, Hu J, Xu J, Li Y, Liang M. Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Pro-Poor Tourism Villages in China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(23):15953. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315953

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Lei, Jing Hu, Jiahui Xu, Yannan Li, and Mangmang Liang. 2022. "Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Pro-Poor Tourism Villages in China" Sustainability 14, no. 23: 15953. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315953

APA StyleZhu, L., Hu, J., Xu, J., Li, Y., & Liang, M. (2022). Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Pro-Poor Tourism Villages in China. Sustainability, 14(23), 15953. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315953