Abstract

The article investigates the possibilities of re-activating the built heritage of the Marche Apennine through shared, creative, and transcalar approaches. This is a particularly challenging task for marginal inner areas, which during the pandemic have been even more isolated due to previous structural issues such as lack of services, poor accessibility, economic stagnation, and depopulation. Italian inner areas are also facing an increase in environmental risks linked to ongoing climate change. This work focuses on the Appennino Basso Pesarese Anconetano in the Marche Region as part of the national project “Branding4Resilience”. The research methodological approach entails an exploration of the territory through quantitative and qualitative tools to investigate the possibility of a new reading of the Marche inner area and suggest operation at a local level, without losing the wider perspective on global challenges. This interpretation is synthesized in a territorial portrait that supports visions for the sustainable transformation of the area, and shows the need for shared collaborative approaches for more inclusive forms of living together. Finally, the work proposes built heritage as a trigger for development processes in marginalized territories, thus highlighting the crucial role of design and creativity, through transcalar approaches, to unveil relevant and often hidden resources and to envisage resilient futures for inner areas.

1. Introduction

The global emergency of the COVID-19 pandemic sharpened the condition of marginality and peripheralization of inner areas and territories, which is already a topical debate and a concrete policy for local action all over Europe [1,2]. In Italy, the state of the art on inner areas is advanced, mainly thanks to the process of sensitization brought forward by the National Strategy on Inner Areas (SNAI) [3]. Indeed, this place-based development strategy, promoted by the Ministry of Cohesion since 2014, managed to increase public attention and awareness, as well as start the territorial regeneration of some marginal contexts. Yet, the strategy has sometimes failed to propose effective local actions of enhancement and transformation, which raises a reflection on the need to revise the tools to read marginality and the criteria to assess the most effective policies to oppose it [4]. In the Apennine area, the conditions of depopulation, abandonment, and lack of infrastructure and services are worsened by the high level of seismic and hydro-geomorphological risks. Especially after the 2016 earthquake in central Italy, and even more now with the recent flood of the Misa river in the Marche region, which affects a large territory from central Apennine (Cantiano) to the coastline (Senigallia), the overlapping of these phenomena would require the implementation of coherent and synergistic policies, as well as a high level of competence and readiness to local action, which are instead lacking or scarce [5]. Yet, at European and Italian levels, positive dynamics and reactions to the issues affecting inner territories are noticeable regarding both structural and emergency challenges [6,7,8]. They often rely on hidden qualities and potentials of the territory and involve culture [9], creativity, and heritage [10,11] as potent drivers of development to overcome the conditions of marginality and abandonment, thus interlacing and connecting local issues to larger frameworks of sense with a transcalar approach [12].

In reflecting on these premises and focusing on the main question of reactivating built heritage with shared, creative, and transcalar approaches, this article explores the northern part of the Marche Region in central Italy as a paradigmatic case to articulate the research question in three sub-questions:

- Is a renewed reading of the Marche inner area possible, and with which tools?

- Can this interpretation be synthesized in a territorial portrait that supports visions for the sustainable transformation of the area?

- Can the reactivation of built heritage be a trigger for development and re-settling processes in marginalized territories, such as the Apennine inner area?

In this context, there is both the need for a new perspective and interpretative framework on inner areas and for a different methodology based on the combination of quantitative and qualitative tools. Indeed, together with more standard tools of mapping and analysis, shared, creative, and transcalar approaches [13] for the investigation of inner contexts are used in the present research to enable a necessary, complex, multifaceted, and systemic view of the territory. This facilitates explorative and transformative scenarios, which are particularly useful to imagine the reactivation of built heritage and to address more resilient futures [14] with the help of local actors and communities [15].

This research is developed within the framework of the national research project “Branding4Resilience” (B4R). B4R examines four Italian inner areas and their ability to adapt to main global challenges by building “operative branding actions”. The capacity for the reactivation of built heritage is a particularly challenging task, especially for rural-mountain areas, which during the pandemic have been even more isolated and left behind, due to structural issues [16,17]. Beyond touristic enhancement, branding starts from identity values, intrinsic qualities, and unexpressed potentials to propose a more structural and resilient transformation of the territory, and connects the idea of heritage reactivation to the one of place-making in a multidisciplinary, transcalar, and multilevel process. In the B4R project, communities are essential to recognize, transform, and take care of local values and built heritage, and thus become a key player in the process [18].

The analyses described in this contribution have been conducted in the focus area of the Appennino Basso Pesarese Anconetano in the north of the Marche Region, Italy, as the specific contribution of the Marche Polytechnic University research unit to the B4R project. Together with the spatial analysis of the focus area and its critical aspects and values, the exploration also detected positive social innovation trends and dynamics of change. Starting from this dataset, the article attempts to sketch a territorial portrait of the area according to a necessary new perspective on inner territories, as mentioned above.

The article is structured in six sections. Section 1 introduces the research question, articulated in three sub-questions. Section 2 focuses on the paper background and clarifies the main objectives of the research. Section 3 presents the methodology, with quantitative and qualitative tools revolving around a ‘research by design’ approach. Section 4 presents the area of Appennino Basso Pesarese Anconetano as a paradigmatic case study for this research. The results in Section 5 synthesize the exploration phase with territorial mapping, photos, diagrams, explorative designs, and a tentative territorial portrait. Results are discussed and critically interpreted in the Section 6 that highlights the need to reposition design at the center of programmatic frameworks for inner areas in combination with a strategic and transcalar approach, which points at built heritage, creativity, and new networks as viable solutions to reduce marginality and generate economic impulses and circular metabolisms.

2. Background

2.1. Peripheries: Habitats of Resilience

In common sense, the word “periphery” is generally associated with marginal, underdeveloped contexts. According to Eurostat, about 58% of the European population live and work in ‘rural areas’ and in ‘towns and suburbs’, which are respectively considered as ‘thinly populated areas’ and ‘intermediate density areas’ [19]. In Italy, as highlighted by the SNAI [3], these marginal areas host more than 13 million people and occupy more than 60% of the national territory. During the recent pandemic, inner areas have shown to be unexpectedly prompt to respond to the basic needs of local communities (social relations, quality of space and living, access to basic services), but at the same time, they have manifested their structural weaknesses (digital divide, inaccessibility). This highlights that the dimension of proximity embedded in these contexts can be seen from a double perspective: it means closeness, intimacy, and sense of community, but this quality is paradoxically the result of isolation, a lack of accessibility, and attractiveness. Abandonment and structural decline are still inevitable critical issues in these areas [20,21,22], but these rural-urban systems have shown also positive dynamics of transformation and innovation in different fields [23] and have started to witness processes of re-settlement with new young incomers in search of job opportunities and diverse lifestyles [2,24,25]. The expansion and relevance of the phenomenon of marginality, in different definitions and connotations, implies that these contexts represent a significant case study in relation to their potentials (e.g., social innovation practices) and with the goal of a possible renaissance and re-settlement [4,26].

Following these considerations, this article aims to look at the peripheral Marche central Apennine as a test-field for new dynamics of development, with potential resources specifically connected to space, settlements, landscapes, and communities. To frame this interpretation, this research draws upon the two background concepts of habitat and resilience. Our understanding of habitat integrates natural space with communities, settlements, and landscapes [27,28]. To define it, we introduce the idea of Slow-Living Habitats [29] characterized by low population density, widespread rural patterns [30], multiple small and medium-sized productive activities, and a variety of settlement typologies alternating in the landscape. These contexts seem to move at a slower pace, but they are not static [31]. They propose instead different productive models and a different way of living, based on the principles of quality of life and relationship with the landscape, zero-kilometer production chains, sustainable tourism, and the enhancement of creativity [32]. Indeed, slowness as a creative rhythm becomes a connecting dimension between human beings and inhabited space and between local and global dimensions, to meet the challenges of our time.

In the field of spatial and local development [33], we relate the term ‘resilience’ to habitats with a higher quality of life for the inhabitants, where circular economies are fostered, slowness is a lifestyle and a productive dimension that generates sustainable and long-lasting processes, and mobility is a synonym for accessibility. Also, resilience stands for the seeking of a renewed balance between human settlements and natural systems and between the preservation of land and the necessary transformations of the living habitat. The expression ‘designing resilience’ means to preserve some of the qualities of the habitat and allow other aspects to fade away while maintaining the same sense of identity [34]. The process towards a shared idea and a vision of the territory [35] that aims at the reconnection of its different layers and complexities is collaborative, and the role of the designer is relevant [36]. It addresses the co-creation of shared scenarios for future development to foster authentic engagement, participatory governance, and self-recognition in the design outcomes, as well as a renewed cohesion of the community in the long term, which in turn triggers an increased capacity to withstand economic, social, and climate challenges [37].

2.2. Goals: Reactivating and Resettling

Although the term “reactivation” might not be common in the terminology for heritage-led processes and interventions on built heritage, this research introduces an approach where built heritage is interpreted in an open and flexible way, including not only listed architectural monuments, but also the architecture linked to the identity of a specific place or community; built heritage is concerned with “more than rationality” and has to deal with “the sense of beauty” [38].

The term reactivation includes different ideas and intervention approaches on built heritage:

- -

- restoration and conservation of the historical heritage, concerning the preservation of building features that have a recognized value and identity [39];

- -

- the more common expression of ‘adaptive reuse’, that combines the preservation of preexisting buildings with new features tailored to the user’s needs [40];

- -

- spatial and functional repurposing and transformation of heritage buildings and structures [41,42];

- -

- recycling abandoned, underused, or polluted artefacts, which refers to the inventive capacity of design to create a new sense for existing objects and spaces [13];

- -

- regeneration [43], which is more commonly used for the urban and landscape scale, and reclamation in their broader sense, referring to the habitat where the built heritage is embedded, which also means the need to connect with the surrounding ecosystem;

- -

- the idea of circularity of design [44], and thus the resilience of the place.

Reactivation can be intended as a multi-layered approach able to reverberate in the territory, while being impacted by the economy and job sector, and having durable effects on the metabolism of the place. The term reactivation and the underlying concept addressed in this article ultimately point at the possibility of resettling as the final goal of the whole process as a final result of the B4R project [18]. The approach envisaged the reactivation and resettling goals to include community engagement and sharing to align ideas towards common development scenarios.

Indeed, B4R innovation lies in the collaborative practices of “co-design” and “co-visioning,” which actively involve the population in the design process, thus facilitating dialogue, exchange, and the promotion of new governance models that aim at transforming stakeholders to “shareholders” and “net holders” [45]. Through creative and transcalar approaches that connect the inventive capacity of design—with minimal interventions—to the large-scale and complex territorial systems where built heritage is located, it is possible to achieve the reactivation and the repopulation of an area.

3. Methodology

The methodology of selection and exploration of the focus area is connected to the general methodological approach jointly developed and used by all research units for the first phase of the B4R project. The methodology uses a combination of quantitative and qualitative tools revolving around a “research by design” approach [46,47,48], and is structured upon four explorative dimensions. The territories are analyzed by looking at:

- Infrastructures, landscape, and ecosystems (dimension 1);

- Built and cultural heritage and settlement dynamics (dimension 2);

- Economies and values (dimension 3);

- Networks, services, community, and governance models (dimension 4).

These lenses integrate all the tools of analysis and, with particular reference to territorial mapping. They are organized in sub-dimensions as extensively clarified in the general methodological overview proposed in the article “Branding4Resilience” [18]. The qualitative tools are field research, perceptive, narrative exploration, and explorative design [49], which are used as scientific tools of knowledge and visioning to obtain a comprehensive analytical framework.

Quantitative and qualitative tools of analysis are carried out in parallel to get a deep and extensive understanding of the area and its dynamics of change [50,51]. With the exploration phase, tangible and intangible meanings are unveiled to build upon regenerative ideas in the following phases of the B4R project, i.e., the co-design phase (2021–2022) and the co-visioning phase (2022–2023). The selection of the Apennine focus area for the Marche Polytechnic University (see Section 4), with its distinctive features and the specific topic of investigation for the research unit, centered around built heritage, and it was required to adapt and specifically address the general B4R methodological approach while remaining within its general framework.

The Quantitative and Qualitative Tools

In B4R explorative approach, the quantitative tools aim to deepen and portrait the current situation of the area. The definition of a set of interpretative maps, generated through specific data/indicators, has been the common starting point to guide and coordinate all research units of the project in a clear methodological framework for the exploration of the four focus areas of the project (Marche, Piemonte, Trentino, and Sicily). The creation of maps based on geographic information systems has been essential to represent geophysical and quantifiable data in a dynamic, interactive, and variable way, and to make them transferable and usable for the municipalities. Data were collected via national, regional, provincial, and municipal portals, but also developed from bibliographic research, tabular data, field trips, and interviews with local actors, and thus represent a completely new source of knowledge of the area.

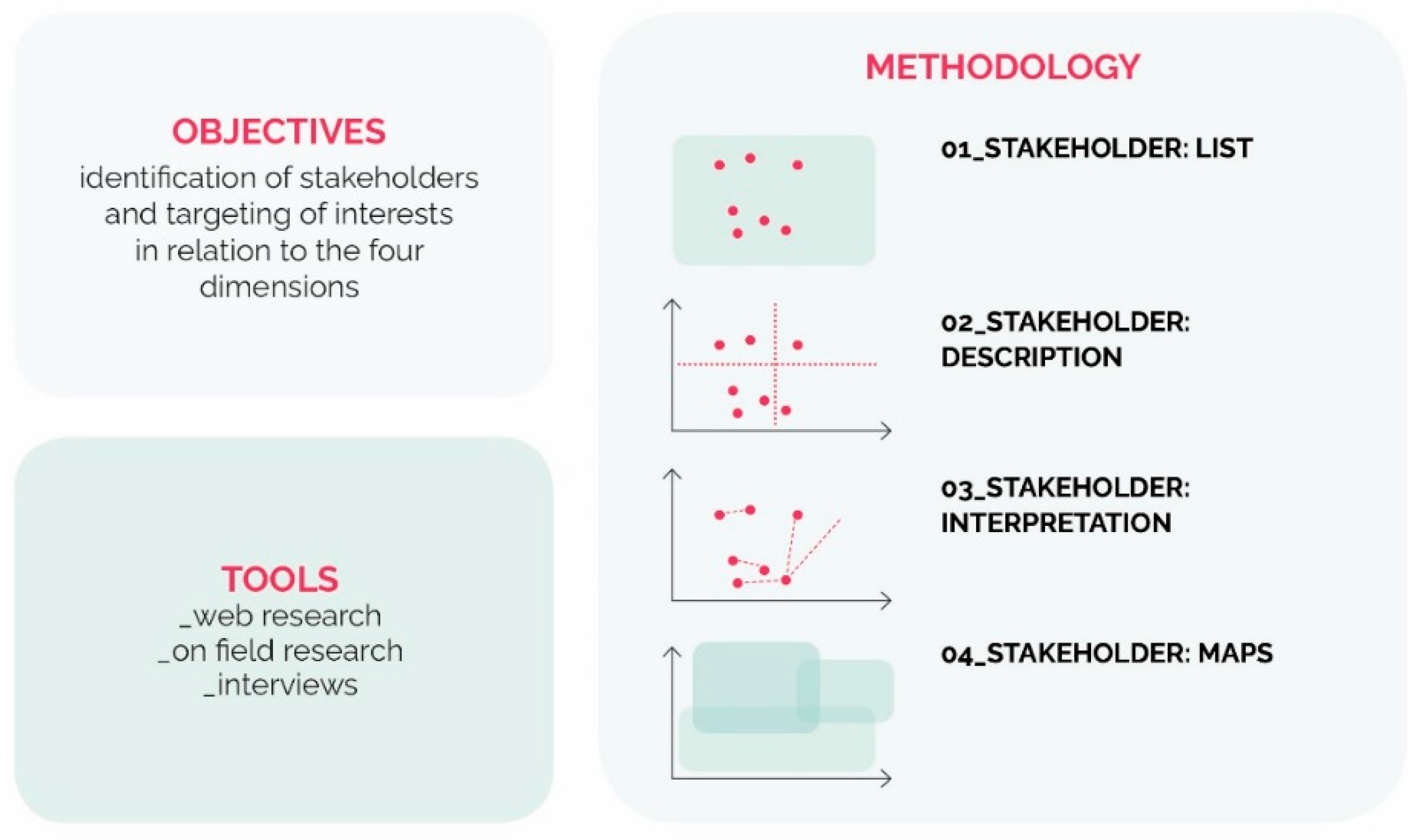

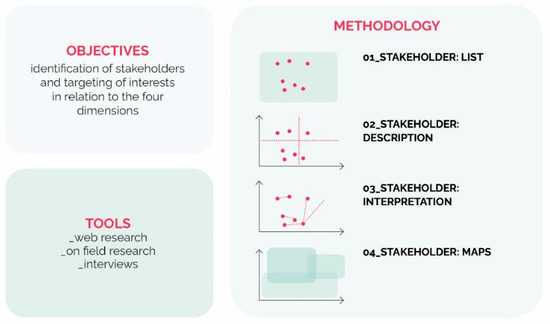

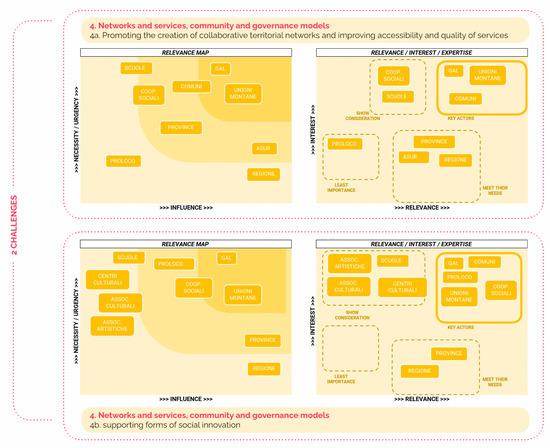

Stakeholder analysis [52] (Figure 1) aims at identifying the key players in the focus area. The analysis detects potential interlocutors who can influence decisions or outcomes on project-related issues. The analysis, a reiterative process, was based on the four dimensions of the explorative phase to suggest stakeholders according to their role and mission. The analysis highlights the relational dynamics between stakeholders and the territory, and points out those main actors with whom dialogue is necessary for the realization of the project [53]. Also, this analysis is useful for the co-design phase to identify groups of subjects that might be involved to discuss and get feedback on the envisaged design actions. Dialogues with local actors support or complement the analysis of stakeholders detecting other potentially interesting subjects through snowball techniques. The focus of the stakeholder analysis and of the dialogues was on “social innovators” or “changemakers”, namely actors that contribute to the dynamic transformation of the area with their everyday activities. The pool of information gathered, both through data collection and dialogues, would lead to the definition of a map of the social innovators [54,55,56,57,58], which is useful for involving these actors in the co-design and co-visioning of the focus area.

Figure 1.

Stakeholder analysis methodology. Credits: coordination M. Ferretti, elaboration C. Rigo, 2021, ©Branding4Resilience—UNIVPM, 2020–2023.

Qualitative tools of analysis are a relevant part of the “research by design” approach used for the area’s exploration. Field research and site visits are used to directly experience the places supporting the researchers in constructing a perceptive analysis of the space and the embedded relational dynamics [30]. Data were collected in situ, including dialogues and informal exchanges with inhabitants and local actors. The point of view is that of the observer [59,60] to construct a vision free of preconceptions. Primarily, preparation must be case-specific, and a certain level of rigor is required to read and interpret the data collected during the site visit.

Perceptive and narrative exploration is performed by means of a professional photographic campaign to build a portrait gallery of the focus area and through storytelling and pattern analysis [30]. Photography is frequently employed in the design process as a perceptive tool for the construction of qualitative analysis; following the Ghirri approach [61], the research proposes the photographic image as a tool for knowledge and interpretation of a specific territory.

Storytelling is used as a tool of cognitive investigation and communication [62], to refocus issues and shift perceptions of places, and ultimately to envisage new transformations inside the design process. In particular, the explorative storytelling activities concern a general look at the territory of the Appennino Basso Pesarese Anconetano, and some specific studies in the villages of Cagli (PU), Cantiano (PU), and Sassoferrato (AN).

As mentioned, a “research by design” [46,47,48] approach is used in all B4R phases. In the Apennine, with architecture and built heritage as the disciplinary focuses of this research unit, we also approach the focus area using explorative design, a tool used to both analyze the territory and envisage its development paths in collaboration with the community to create further connections [52]. Particularly Ph.D. research studies [29,63] substantiate this approach in coordination with the methods, tools, and focus of B4R [18] and are partially supported by the work of design master theses that helped test specific solutions. The use of this tool builds upon the methodology used by some of the authors in previous transdisciplinary research projects [64]. The creative and transcalar approach at the basis of these explorations suggests going beyond single building to embrace a wider strategic perspective on the context. This creates the framework to enrich the architectural intervention with a stronger sense and purpose by embedding it within specific and contextualized visions of the studied habitat. The explorative design focuses on the whole focus area and on specific looks at six of the nine municipalities of the Appennino Basso Pesarese Anconetano.

4. The Northern Central Apennine: A Paradigmatic Case Study

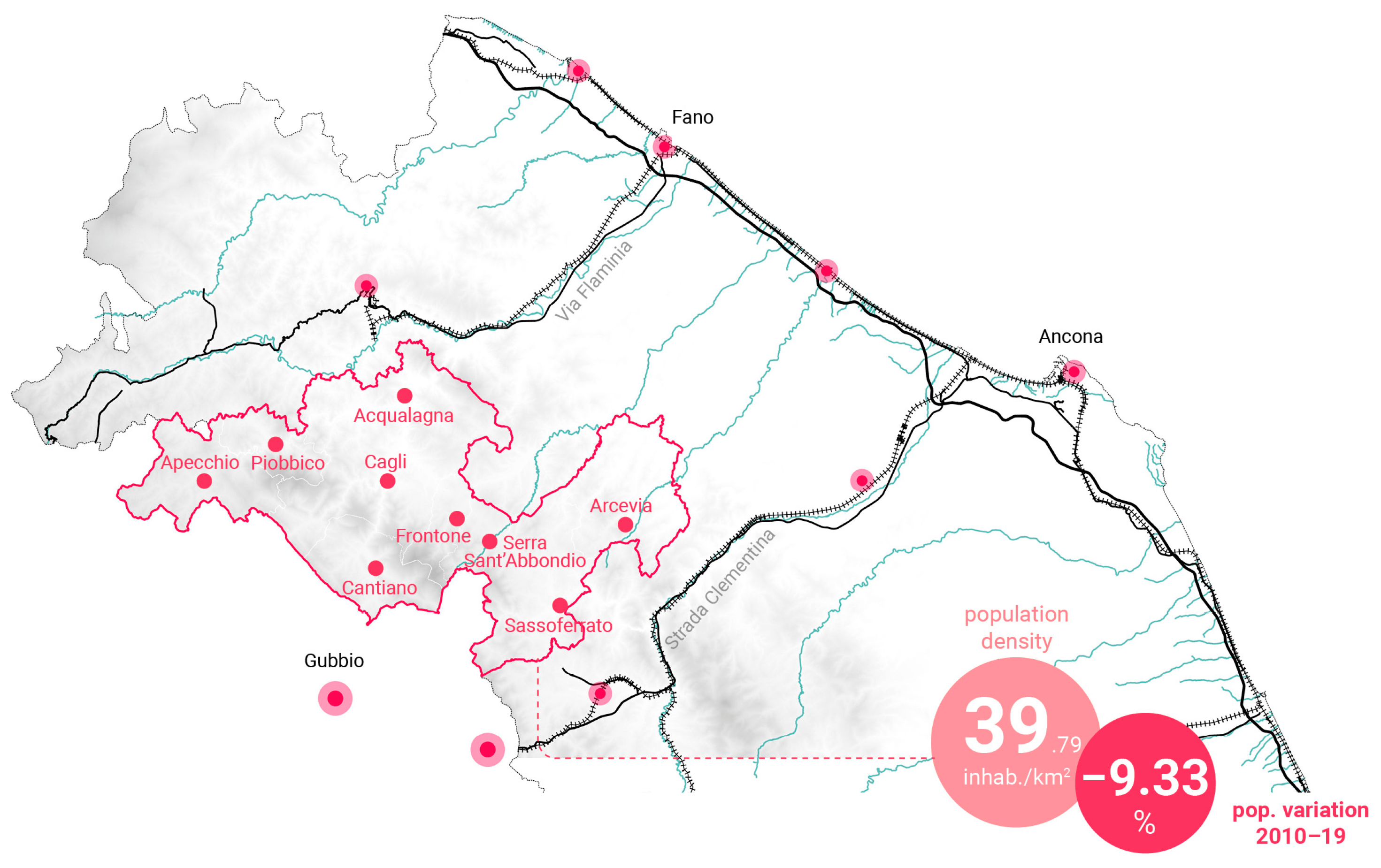

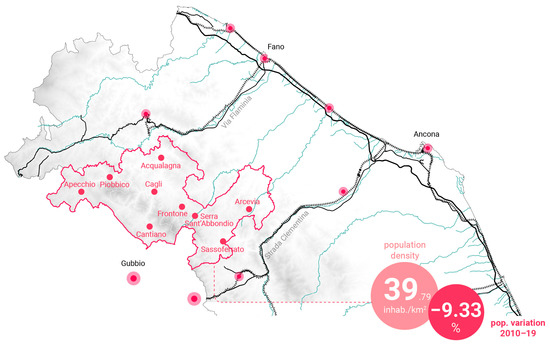

The selection of the focus area for the Marche Polytechnic University was related to the general framework of criteria set within B4R: inner territories characterized by low-density population that are affected by phenomena of abandonment, economic setback, lack of services, and reduced accessibility. The Appennino Basso Pesarese Anconetano (Figure 2) consists of nine municipalities with a 846.15 km2; extension and 32,375 residents (Istat 2019). It has an average population density of 39.67 inhabitants/km2 and it is the Marche Region’s pilot area for the SNAI. Located in the northern central Apennine, the area is strongly linked to the two centers of Urbino and Fabriano, and it is tangentially touched by the Roman Via Flaminia and the consular road Strada Clementina. It is also placed within the identifying river comb structure, with productive, ecological, and linear infrastructural valleys connecting it to the coast and supporting its capillary economy of small-medium enterprises typical of this region.

Figure 2.

The Appennino Basso Pesarese Anconetano focus area of the Marche Polytechnic University in the B4R project. Credits: coordination M. Ferretti, elaboration M.G. Di Baldassarre, C. Rigo, 2021, ©Branding4Resilience—UNIVPM, 2020–2023.

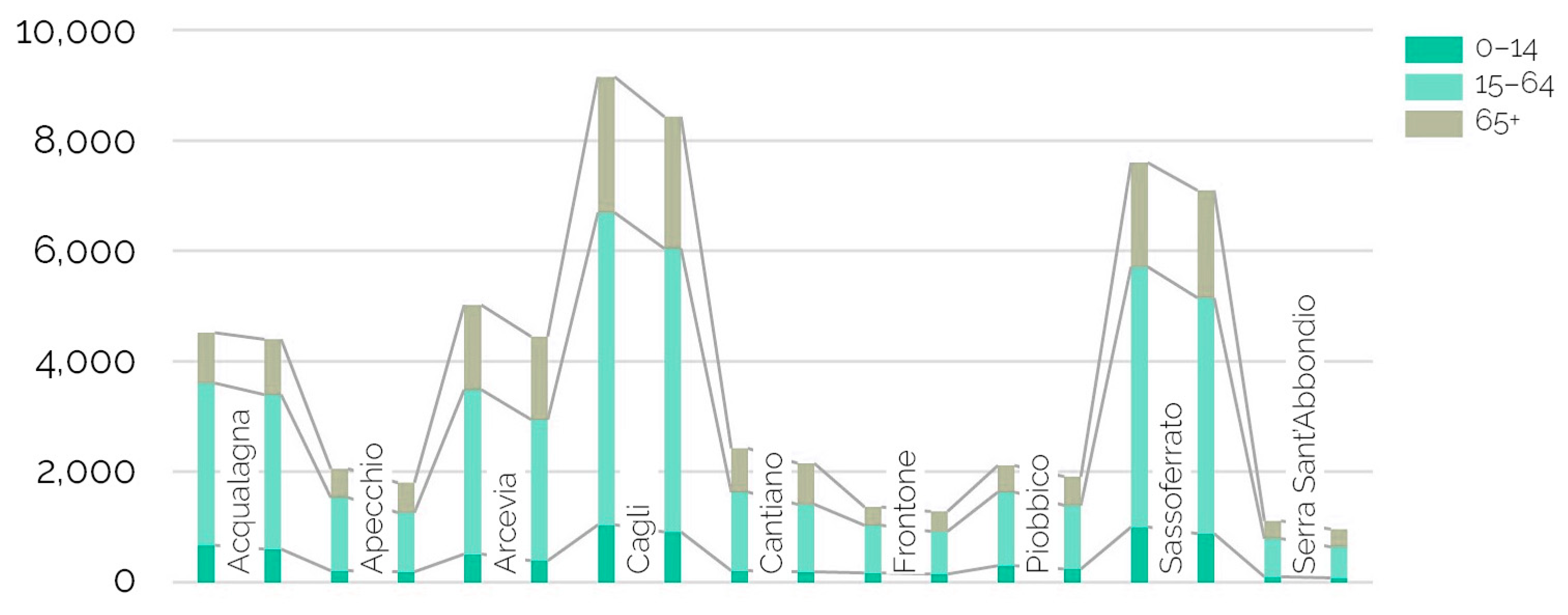

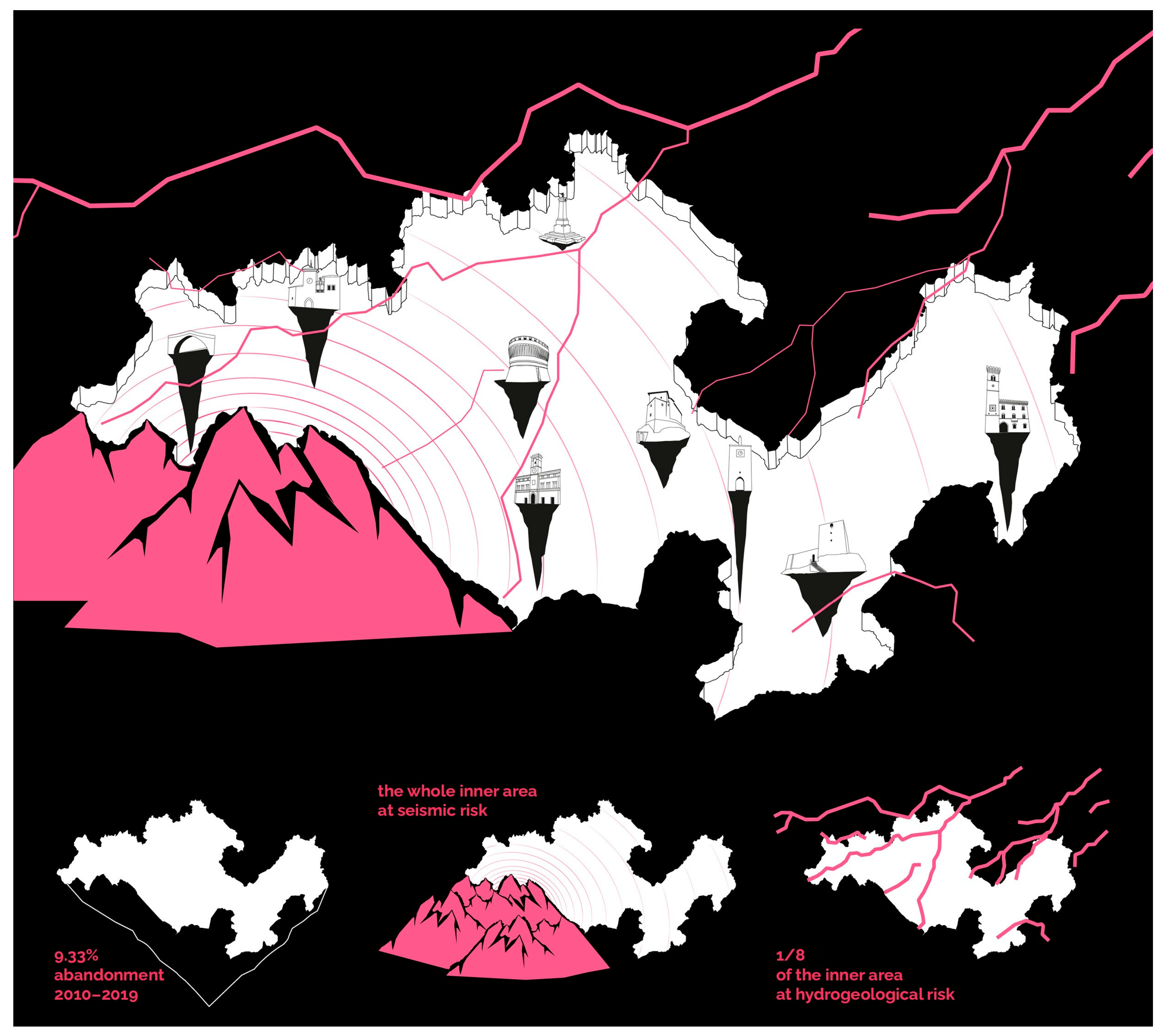

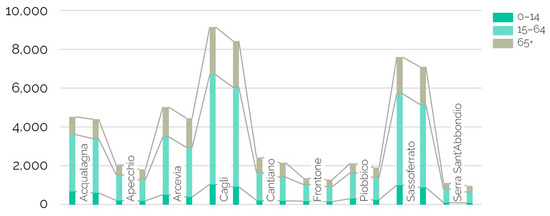

The small centers and rural villages (Figure 3) face a slow and extended process of marginalization. The lack of offered education and the medium distance of 24.65 km from the DEA hospitals (Department of Emergency and Acceptance) are significant indicators, combined with the critical seismic and hydrogeological conditions of the central Appennine. The fragility is revealed by the progressive aging population, with an increase in the average age from 45.52 to 48.37 years old, the significant increase in the over-65 population (Istat 2002–2019), and the average depopulation of 9%, with has peaked up to 18% (Figure 4). These demographic processes impact the local economic development and the governance system, which lead to a general impoverishment of both heritage and natural assets.

Figure 3.

A drone view on the historic fortress of Frontone (PU) and the surrounding landscape. Photo by A. Tessadori, 2021, ©Branding4Resilience—UNIVPM, 2020–2023.

Figure 4.

Population variation articulated by age group during the period 2011–2019 (ISTAT, 2011–19). Credits: ©Branding4Resilience—UNIVPM, 2020–2023, coordination M. Ferretti, data processing and elaboration M.G. Di Baldassarre, C. Rigo, 2021.

5. Results

Besides providing an overview of the results collected in the exploration phase, the article proposes in this section a focus on the analysis of the built heritage dimension (dimension 2) of the Marche Region, both to outline the most significant asset for the focus area and to stress the semantic connection with the critical interpretation of data synthesized in the territorial portrait (Section 5.4).

5.1. The Territorial Mapping and Analysis: Built Heritage as an Asset

The territorial mapping of the Appennino Basso Pesarese Anconetano is a collection of maps, textual descriptions, graphs, and data describing the habitat in order to catch its positive and critical aspects and to consider its interdependencies through a transcalar multidisciplinary perspective. By looking at the distribution of the mapped data, it is possible to detect patterns, trends, and dynamics of the area for a necessary renewed reading of these marginal habitats.

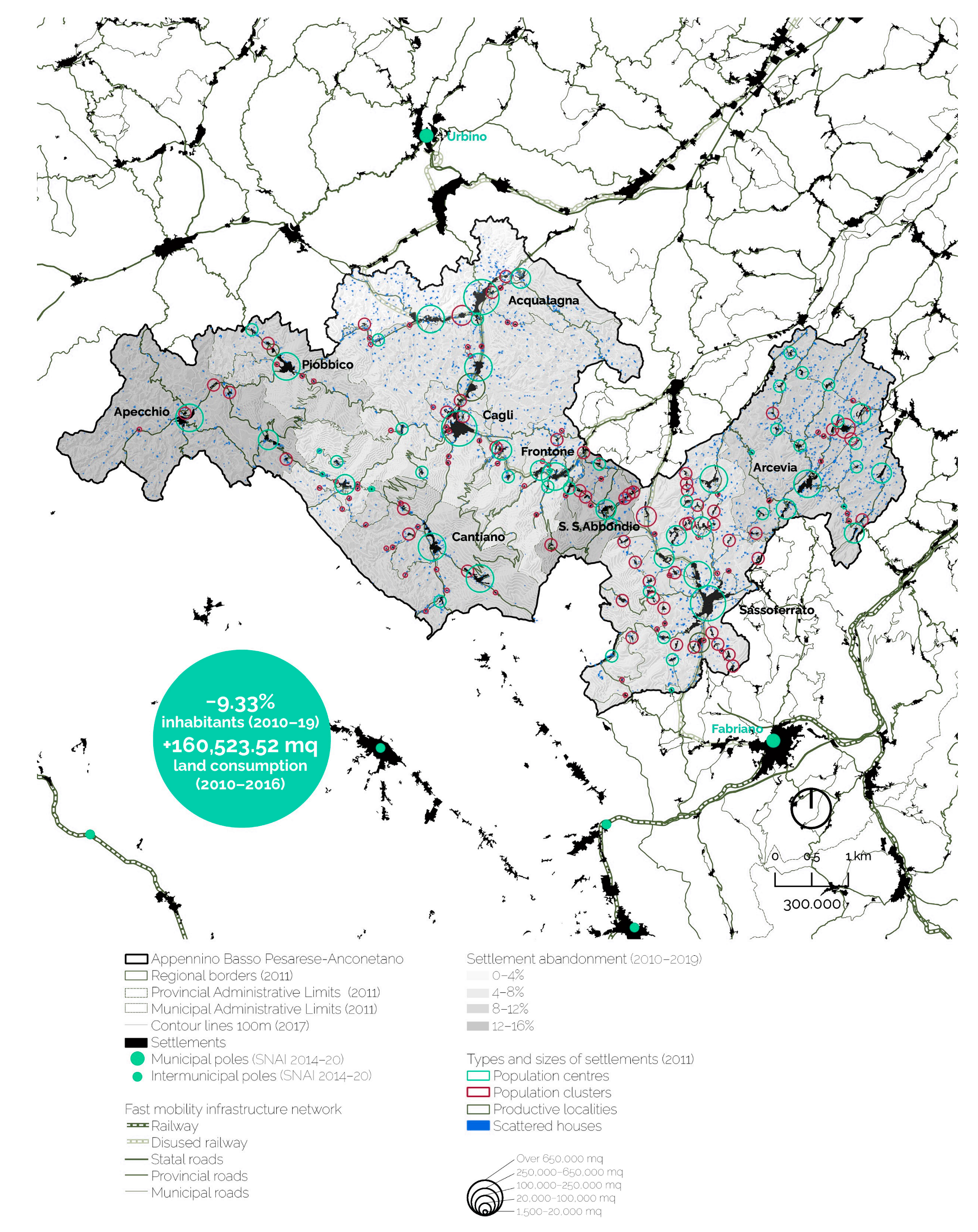

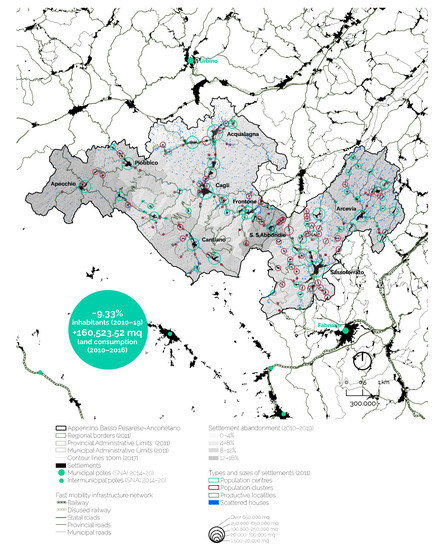

The settlement structure (Figure 5) is characterized by small centers and rural villages, but also by small productive localities and a constellation of scattered houses. All the municipalities are facing a slow process of marginalization and an abandonment phenomenon (−9.33% inhabitants, from 2010 to 2019). This process goes paradoxically along with extensive land consumption. Although there has been an evident development of all the major urban centers following the Second World War, even in recent decades, land consumption has risen to 160,523.52 m2. This data is even more critical when considering the significant percentage of abandoned, underused, or disused buildings and urban voids.

Figure 5.

Structure and transformative dynamics of settlements. Credits: coordination M. Ferretti; data processing (Istat 2011–19, Tinitaly 2017, CTR Regione Marche 1999–2000, Geoportale Nazionale 2020, Grafo della Viabilità Regione Marche 2011, Atlante Consumo del Suolo Regione Marche 2011–16) and graphics: M.G. Di Baldassarre, C. Rigo, 2021, ©Branding4Resilience—UNIVPM, 2020–2023.

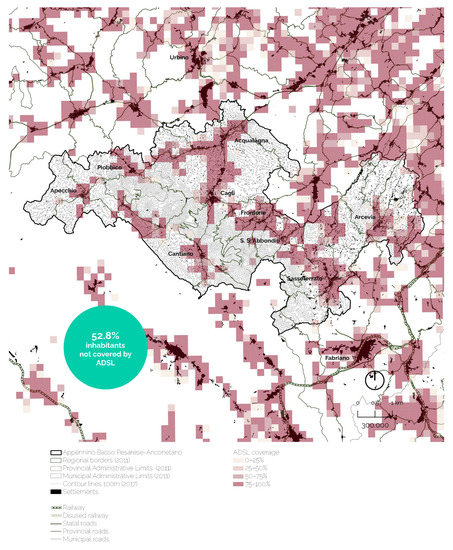

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the issue of technological infrastructure and communication networks has become a central topic, which highlighted how inner areas lacking these systems found themselves in a condition of further marginalization. At the same time, other regions recognized the experimentation of new living and working models, such as smart or south working [65]. Within the focus area, DSL coverage (Figure 6) was extremely high in the main centers, while in the more peripheral areas it was almost non-existent and reached less than 50% of the inhabitants. Regarding this, the municipalities are implementing new possibilities for innovative development.

Figure 6.

Technologic infrastructure and telecommunication networks. Credits: coordination M. Ferretti; data processing (Istat 2011, Tinitaly 2017, CTR Regione Marche 1999–2000, Geoportale Nazionale 2020, AGCOM Autorità per le garanzie nelle comunicazioni 2020) and graphics: M.G. Di Baldassarre, C. Rigo, 2021, ©Branding4Resilience—UNIVPM, 2020–2023.

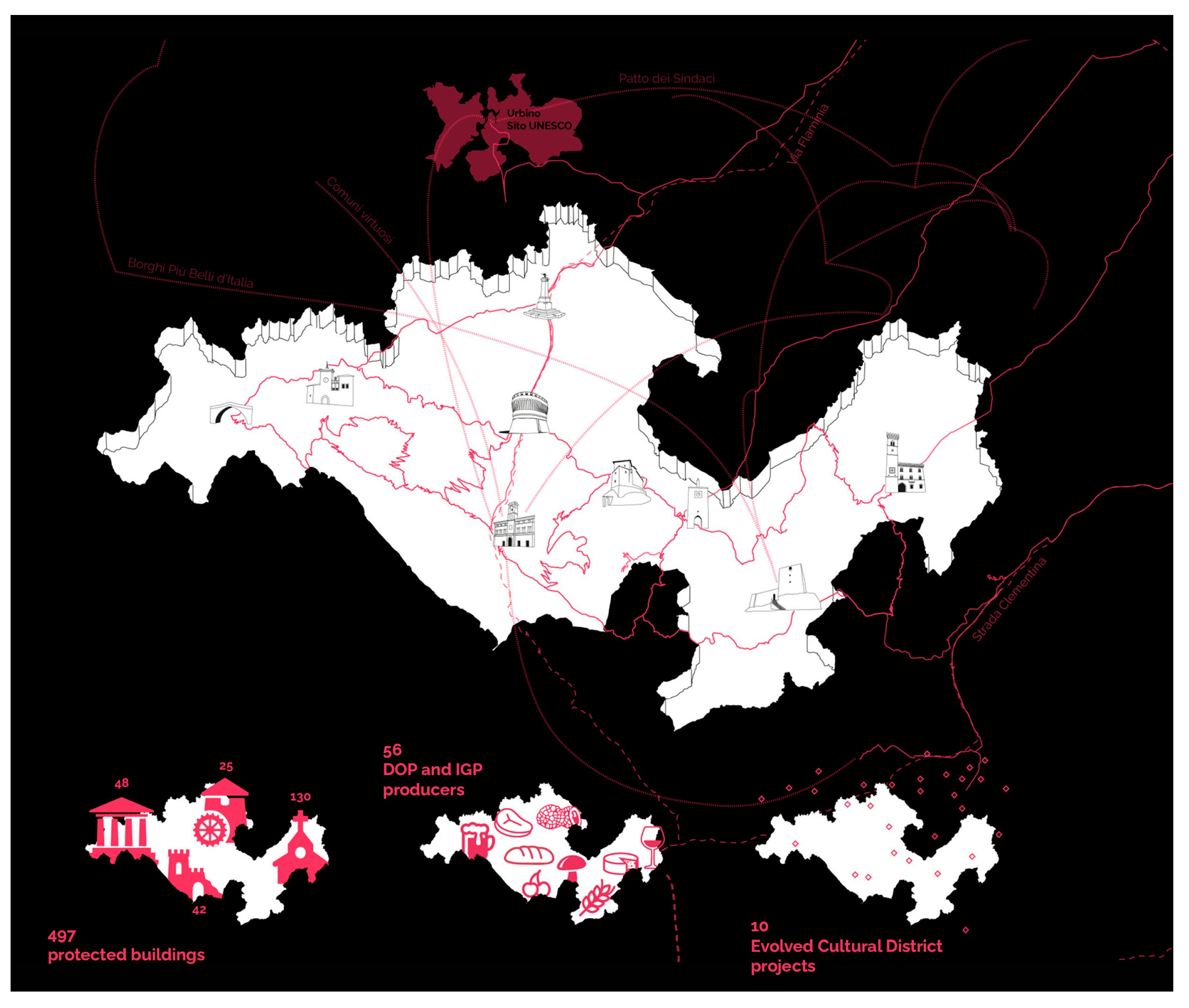

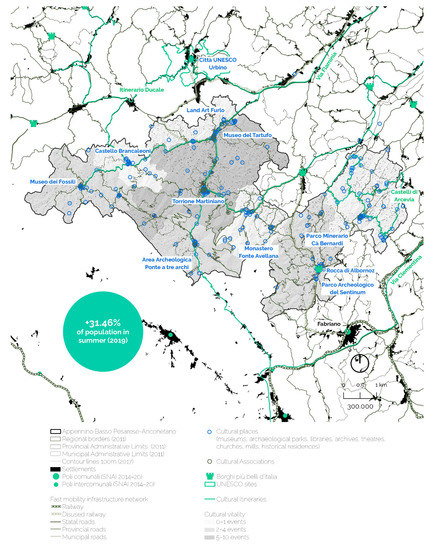

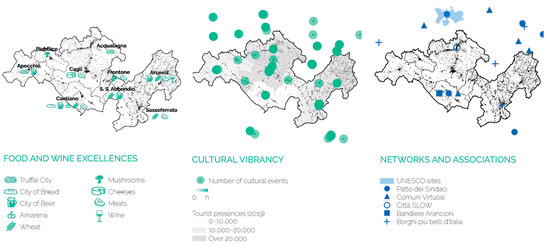

The area is close to the UNESCO site of Urbino and other centers that are part of the national networks “Borghi più Belli d’Italia” (Sassoferrato), and “Comuni Virtuosi” (Cantiano), as shown in Figure 7. Food and wine excellence enable these territories to be included in international production networks. Also, the organization of international events enhances tourist attractiveness, especially in the centers with the highest cultural interaction, which is measured by the number of active associations. The population increase in the summer was more than 30%, and mainly due to the number of tourists attracted by the large offer of cultural sites, historical built heritage, events, historical and cultural itineraries, local food and wine excellence, and traditions (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Cultural networks, places and activities. Credits: coordination M. Ferretti; data processing (Istat 2011–19, Tinitaly 2017, CTR Regione Marche 1999–2000, Geoportale Nazionale 2020, Grafo della Viabilità Regione Marche 2011, Government Open Data Regione Marche 2020, Servizio WMS Vincoli in Rete Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali 2019, ViviMarche 2020, Osservatorio Regionale delle politiche sociali della Regione Marche 2009–19, Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali 2013, ScuolaInChiaro.it 2019, TuttItalia.it 2020, stakeholders interviews 2020–21) and graphics: M.G. Di Baldassarre, C. Rigo, 2021, ©Branding4Resilience—UNIVPM, 2020–2023.

Figure 8.

Food and wine excellence, cultural vibrancy, networks and associations. Credits: Coordination M. Ferretti; data processing (Istat 2011–19, Tinitaly 2017, CTR Regione Marche 1999–2000, Geoportale Nazionale 2020, Grafo della Viabilità Regione Marche 2011, Government Open Data Regione Marche 2020, Servizio WMS Vincoli in Rete Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali 2019, ViviMarche 2020, Osservatorio Regionale delle politiche sociali della Regione Marche 2009–19, Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali 2013, ScuolaInChiaro.it 2019, TuttItalia.it 2020, stakeholders interviews 2020–21) and graphics: M.G. Di Baldassarre, C. Rigo, 2021, ©Branding4Resilience—UNIVPM, 2020–2023.

The exploration has brought attention to the focus area’s complex cultural system, determined by its built heritage, natural assets, cultural values, and creative vibrancy. This vast capital represents a fundamental opportunity for the inner area, if funding and investments are correctly addressed. The specificity of the built heritage is a main asset, and its reactivation may generate positive multiplier effects to become a driving force for an overall rethinking and adaptation of the Apennine settlements to new performances of efficiency, accessibility, innovation, and inclusion.

5.2. The Research in the Field: Social Innovators and Change-Makers for Collaborative Networks

As described in Section 3, the research group conducted field research in the Appennino Basso Pesarese Anconetano (Figure 9) region on September 2020. The on-site surveys evidenced a landscape strongly shaped by the presence of human settlements, with ongoing depopulation signs. The decline in land preservation was visible among the uncultivated spaces and abandoned buildings. The difficulty of accessibility increases the risk of marginalization. Yet, many diffused qualities and potential spaces built a constellation of beautiful places, rich in aesthetic values, full of identity and significance for the communities and that opened unexpected pockets of possibilities.

Figure 9.

Itinerary of the first survey of the Appennino Basso Pesarese Anconetano, and views evidencing qualities and potential spaces in the territory. Credits: Coordination M. Ferretti; graphics M.G. Di Baldassarre; photos C. Rigo, 2020, ©Branding4Resilience—UNIVPM, 2020–2023.

The stakeholder analysis in the Appennino Basso Pesarese Anconetano highlighted a network of several actors potentially interested in the eight challenges identified. We evaluated the interests and the expertise of each stakeholder on a specific topic, and located the subjects on maps that stated the relevance of some key actors (Figure 10). Concerning the creation of collaborative territorial networks and the improvement of accessibility and quality of services, the more involved actors were local public administrators and Local Action Groups. Regarding the topic of social innovation, the range of stakeholders included enterprises and cooperatives working in the third sector.

Figure 10.

Matrixes and key subjects resulting from the stakeholder analysis conducted on the focus area. Credits: coordination M. Ferretti; data and graphics C. Rigo C., 2020 ©Branding4Resilience—UNIVPM, 2020–2023.

Figure 11 synthesizes the relevant issues, possibilities, and weaknesses of the territory in a word cloud that emerged during a series of dialogues with selected social innovators in the area. The main themes in these conversations regarded material and immaterial heritage, local traditions and productions, research, and innovative ideas. Critical issues related to accessibility, isolation, abandonment, and lack of opportunities emerged. The predominant element was undoubtedly linked to the difficulty in creating new networks and synergies between the many positive experiences throughout the territory, thus leading to a lack of real impact of the social innovation initiatives of enhancement and empowerment. Considering this situation, it is necessary to focus on building a network of these actors to bring further innovation to the territory.

Figure 11.

Social Innovators Word Cloud. Credits: coordination M. Ferretti; graphics: M.G. Di Baldassarre, C. Rigo, 2021. ©Branding4Resilience—UNIVPM, 2020–2023.

5.3. The Perceptive, Narrative and Design Exploration: Creativity as a Resource and a Tool

Through the qualitative process described in Section 3, the Apennine exploration identified a series of recurring aspects. The investigation of the interaction between human settlements and nature showed a strict connection between natural elements and built heritage, as well as heavy transformations on landscapes and historical stratifications made by the evolution of uses and economies in the territory. Particularly, the perceptive exploration, using photography and pattern analysis, identified:

- A varied and complex landscape (Figure 12);

Figure 12. Settlements, hills, and mountains in the Appennino Basso Pesarese Antonetta region. Photo by A. Tessadori, 2021. ©Branding4Resilience—UNIVPM, 2020–2023.

Figure 12. Settlements, hills, and mountains in the Appennino Basso Pesarese Antonetta region. Photo by A. Tessadori, 2021. ©Branding4Resilience—UNIVPM, 2020–2023. - Productive activities related to agriculture, forestry, and used or unused quarries;

- A branched network of minor roads, footpaths, and cycle paths, that were realized or under implementation;

- High hydrogeological and seismic risks, also related to urban settlements;

- Several buildings of considerable architectural value—some of which were recovered with a creative approach both for public and touristic purposes;

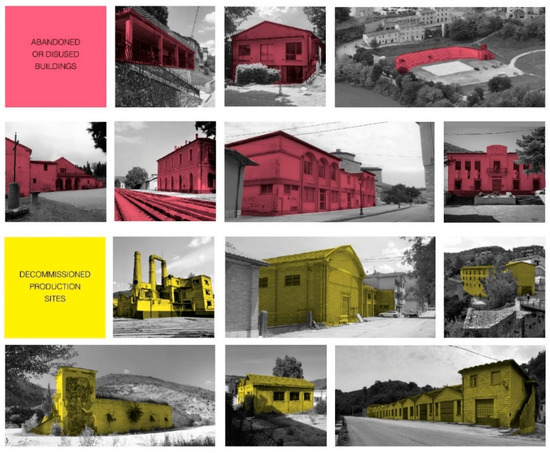

- ‘Ordinary’ heritage, consisting of often abandoned or underused buildings and places that represent an unresolved issue for the historical centers (Figure 13 and Figure 14).

Figure 13. Former pasta factory Giacani next to the historical center of Sassoferrato (AN). Photo by A. Tessadori, 2021. ©Branding4Resilience—UNIVPM, 2020–2023.

Figure 13. Former pasta factory Giacani next to the historical center of Sassoferrato (AN). Photo by A. Tessadori, 2021. ©Branding4Resilience—UNIVPM, 2020–2023. Figure 14. The spaces of possibilities, abandoned industrial sites, and productive heritage detected through a pattern analysis in the whole inner area. Credits: M.G. Di Baldassarre, 2022, ©Branding4Resilience—UNIVPM, 2020–2023.

Figure 14. The spaces of possibilities, abandoned industrial sites, and productive heritage detected through a pattern analysis in the whole inner area. Credits: M.G. Di Baldassarre, 2022, ©Branding4Resilience—UNIVPM, 2020–2023.

The narrative exploration used storytelling as a tool to describe the many ‘characters’ encountered during field investigations. We detected:

- A strong sense of togetherness characterizing this network of small communities rooted in the territory and connected to their villages and the traditions of their land;

- Proximity economic activities, typical of small towns, that acted as meeting places for citizens and often provided essential services for inhabitants and visitors;

- People moving from place to place in a territorial dimension mostly by car to work and reach services, which opened questions about the sustainability of inner territories in terms of accessibility for the aging population.

An important aspect characterizing the focus area was creativity, which was detected as reaching local creatives, artists, and artisans. We also analyzed a quite successful and pioneering action policy promoted within the SNAI. The “Asili d’Appennino—The dwellings of creativity in Upper Marche” is a pilot project involving all municipalities of the area for the creation of a new concept of hospitality through reclaiming and repurposing cultural buildings as new artistic residencies. Based on an integrated management approach, the project combines receptivity, culture and education, enjoyment of the environment and landscape, food products, welfare, slow mobility, and digital services, with the ultimate goal to experiment with new possibilities and ways of living and creating in this territory.

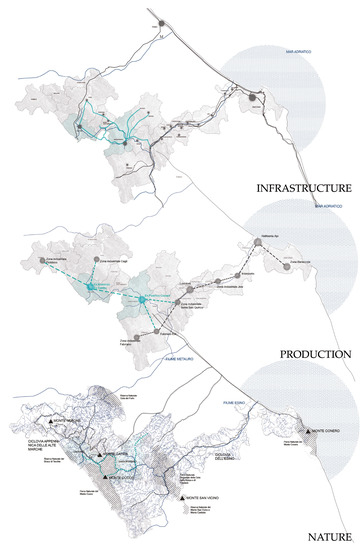

Explorative designs (see Section 3) conducted in the Appennino Basso Pesarese Anconetano highlighted important topics and issues both on specific sites (Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17) and for the whole focus area. The creative and instinctive capacity of design was used here as a tool to identify potential values and hidden qualities. The transcalar approach tried to outline a strategic vision for the territories (scenarios) while defining small-scale operative actions (architectural designs).

Figure 15.

Scenarios of reconnection of the focus area with the Adriatic coastline along the Strada Clementina include the need to act on infrastructure, production, and nature, which are both criticalities and potentials for the territory. Credits: M. Campanelli and B. Staccioli with M. Ferretti and C. Rigo for ©Branding4Resilience—UNIVPM, 2020–2023.

Figure 16.

The reactivation of the market square of Cantiano is based on the transformation of the former wheat mill into a bakery and community center. Credits: B. Staccioli with M. Ferretti and C. Rigo for ©Branding4Resilience—UNIVPM, 2020–2023.

Figure 17.

Abandoned productive heritage is reactivated with new activities. The former agricultural consortium of Apecchio was turned into a fab lab with accommodating spaces and new economic and social activities. Credits: E. Carlino with M. Ferretti and M.G. Di Baldassarre for ©Branding4Resilience—UNIVPM, 2020–2023.

In Cantiano and Sassoferrato, we developed specific responses to critical issues, such as the abandonment of the industrial heritage and the scarce infrastructural connection. Figure 15 displays the strategic scenarios addressing the area’s key topics, namely the main infrastructures along the river valleys, the historical layer of unused or abandoned productive buildings, and the parks and natural reserves. From the scenario-building [49], specific designs for the built heritage of Sassoferrato and Cantiano were envisaged to reactivate two former mills along the rivers Sentino and Burano. In Sassoferrato, the former pasta factory with the embedded mill was proposed as a food and pasta lab linked to the regeneration of the river park and to the implementation of a local food market in the nearby public square. In Cantiano (Figure 16) the former wheat mill is connected to an existing hostel, and both were refurbished and turned into a bakery and a community center, including a space to exhibit and promote the local products sold in the vegetables and fruit market taking place once a week in front of the building.

Thanks to the comprehensive exploration, three relevant topics emerged for the Apennine:

- The rich presence of built heritage, some of which is currently abandoned and in need of reactivation;

- The lack of networks and connections, both among people, actors, and practices, and in terms of physical infrastructures;

- Creativity as a relevant layer and resource of the area.

These analyses have been useful to depict a territorial portrait of the focus area intended as a first interpretation and a starting point towards branding and the necessary structural transformations to increase resilience against future challenges.

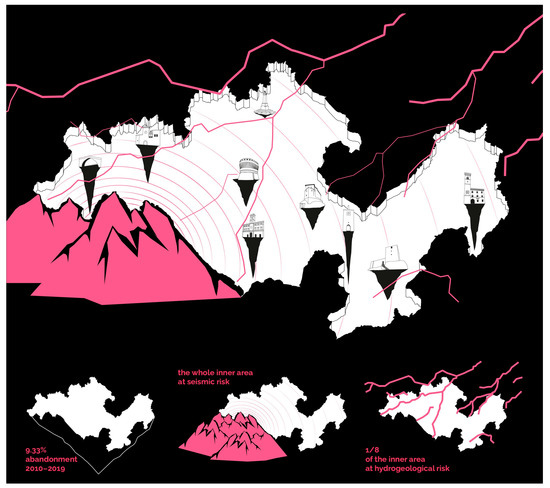

5.4. Built Heritage, Networks and Creativity: A Territorial Portrait for the Apennine Inner Area

The territorial portrait, depicted in the maps of risks (Figure 18) and values (Figure 19), sketches the Apennine as an “archipelago of villages” of floating-like islands in an exceptional, natural, patrimonial, and social context. However, they fluctuate against the seismic waves and are confronted with the typical problems of the islands: inaccessibility, abandonment, anthropic pressure, risk of tourist colonization, and consequent loss of identity (Figure 18). The medieval villages called “borghi” developed around a castle or a fortress and were usually built on a hill, along ridges, or surrounded by rivers, to defend against enemies. The territorial portrait aims to represent the risks of these typical central-Italy villages by symbolically portraying the percentage of listed buildings (2%) compared to ordinary heritage (98%), which shows significant abandonment trends. Yet, seemingly contradicting this figure, land consumption increased (+160,523.52 m2 in the period 2010–2016), which also contributed to the general impoverishment of the landscape values. Also, the portrait displays the isolation of villages in terms of cultural and social networks, as reported during the field research by inhabitants and operators. High hydrogeological risk is represented in Figure 18 by the rivers cutting through the villages. The risk map brings to light a general condition of strong fragility in the “archipelago of villages”.

Figure 18.

Territorial portrait: “an archipelago of villages”. Risk map. Credits: coordination M. Ferretti, elaboration M.G. Di Baldassarre, 2021. ©Branding4Resilience—UNIVPM, 2020–2023.

Figure 19.

Territorial portrait: “an archipelago of villages”. Value map. Credits: coordination M. Ferretti, elaboration M.G. Di Baldassarre, 2021. ©Branding4Resilience—UNIVPM, 2020–2023.

Figure 19 maps the values of the northern Apennine. Identity elements such as castles, bell towers, or fortifications represent the most iconic monuments of each village, sketched in the central drawing. This heritage is recognized worldwide, including the nearby UNESCO World Heritage Site of Urbino and two important historical streets, the Flaminia and the Clementina. Creativity and social innovation are important features, as shown by the regional initiative “Evolved Cultural District”, which have been promoted in the area since 2012. Also, the connection between the municipalities is crucial, and it is represented in the value map by the bike ring-pathway “Ciclovia Alte Marche”, a cooperation project of the nine villages developed within the framework of the SNAI.

Precisely because of this double condition of high value and high risk, the “archipelago of villages” and its ordinary heritage must be protected and enhanced through conservation, but also through the creative capacity of design to transform it sensitively and to reveal its intrinsic and sometimes hidden qualities. Some of these qualities include the creative and entrepreneurial capacity of the inhabitants, the beauty of the places, the architectures and built heritage, the potential of the material and immaterial networks, and the value of the history and culture.

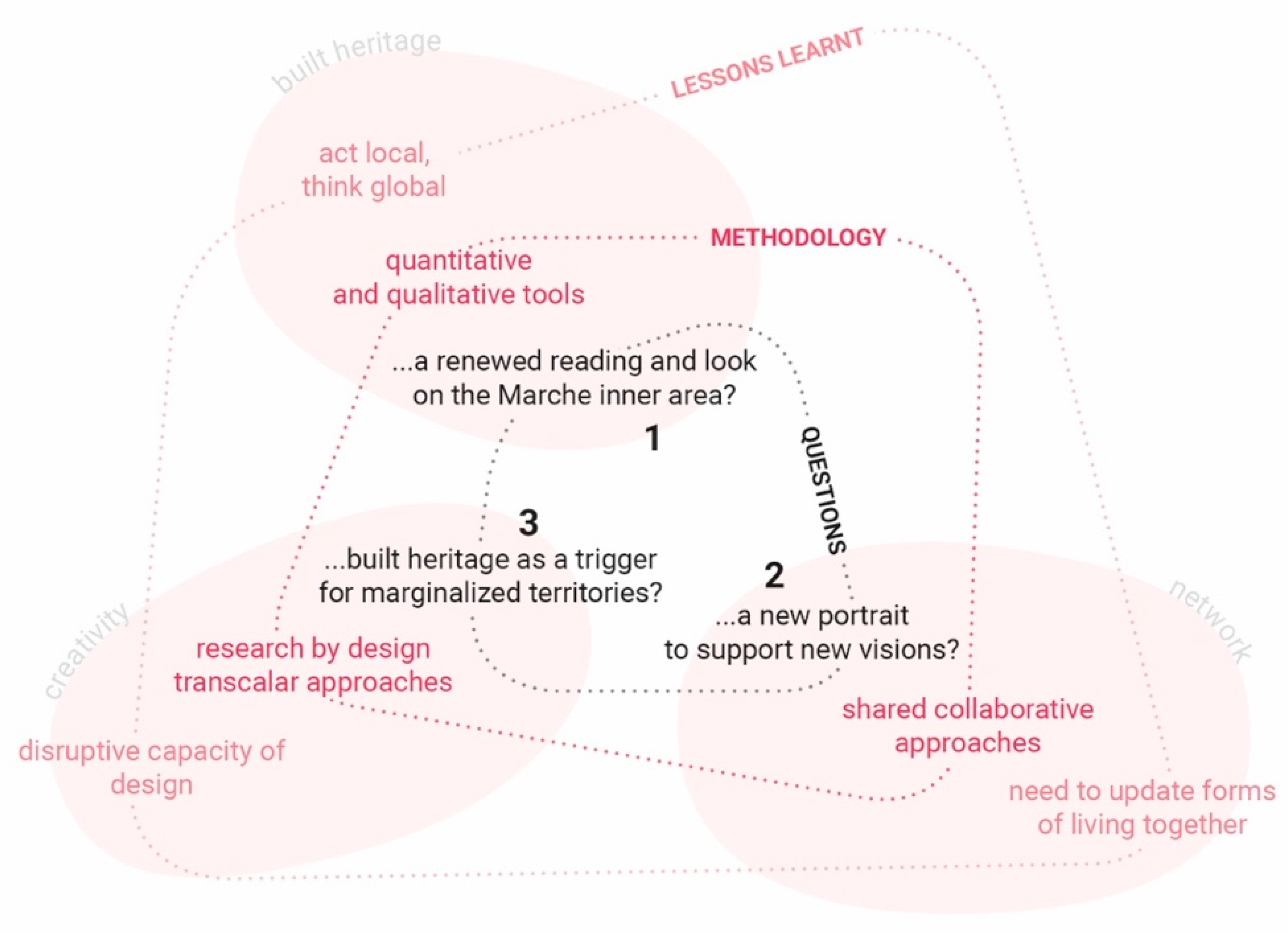

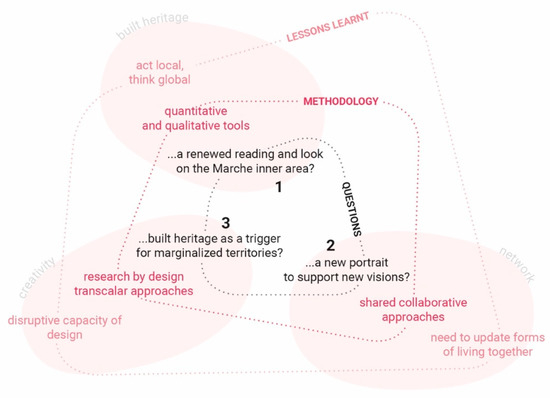

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Lessons Learned

Some significant insights have been drawn from the analysis of this inner area. The lessons learned are summarized in the following articulation, and synthesized in Figure 20, to find an answer to the research sub-questions articulated at the beginning of this article.

Figure 20.

Research question, articulated in the three sub-questions, and lessons learned. Credits: coordination M. Ferretti, elaboration C. Rigo, 2022. ©Branding4Resilience—UNIVPM, 2020–2023.

- First, the research aimed at determining whether a renewed reading of the Marche inner area was possible and how that could be so. This contribution identified quantitative and qualitative tools as necessary tools to reach this goal; through the implementation of territorial mapping, the study of the literature, on-site visits, the exchange with experts, and the dialogues with the communities, it seems that a viable solution and a right approach should combine a focus on local issues and problems to be tackled with a wide-ranging perspective. Working at different scales, it is possible to consider global challenges and to contextualize them by verifying how they interface with local circumstances. From the research, it emerged that the built heritage is a significant asset for these territories. However, some critical issues and potentialities are currently unexploited due to the difficulty of accessibility and the lack of skills necessary for the valorization of the existing heritage.

- Secondly, this contribution investigated the possibility of synthesizing this new reading into a territorial portrait that would be able to support visions for a sustainable transformation of places. The methodology applied shared and collaborative approaches through stakeholder analysis, dialogues, and, as future steps of the B4R project, co-design and co-visioning. The presented results, through stakeholder maps, social innovators diagrams, and word-clouds, evidenced the presence of existing networks on the territory which, nevertheless, appear to be weak. Their strengthening is an ongoing process that deserves to be further supported. The results highlight the need to find alternative forms of cohabitation of places and dialogue among the various actors.

- The third research sub-question wondered about the role of built heritage as a trigger for development and re-settling processes in marginalized territories. The “research by design” methodology implied creative and transcalar approaches. The results (perceptive analysis, portrait gallery, storytelling, pattern analysis, explorative designs, and scenarios) highlighted the relevance of a creative approach to places and the disruptive capacity of design to unveil hidden aspects and topics which are very significant for a more resilient future for these contexts. The promotion of local creativity can be supported by enhancing existing potentials in the area, and with the direct application of design know-how through innovative and transcalar processes.

6.2. Innovation: “Borgo +cheSostenibile”

Our contribution adds a further element of reflection to the ongoing debate on small villages in Italy [66]. With regard to the background literature, we proposed an innovative concept of habitat according to which the village appears to be strictly linked with its territory, and brought forward the idea of slow-living habitats. Also, the idea of resilience has been outlined in this contribution with specific reference to design. Moreover, the research addressed the notions of reactivation and resettlement, while proposing to connect these goals with a systemic and transcalar approach to territories.

By focusing on heritage reactivation through shared, creative, and transcalar approaches, the research aims at the sustainable development of the villages (“borghi”) in a broader sense. We propose the idea of “Borgo +cheSostenibile” (lit. “More-than-Sustainable Village”), a village that overcomes the isolation of the individual settlement and becomes part of a dynamic, participative, and collaborative system. In this vision, the “archipelago of villages” sketched in the territorial portrait should reconnect with its surroundings. Going beyond sustainability (more-than-sustainable) means increasing the villages’ performances in terms of environmental gains—promoting a higher quality of life—and using design in a collaborative and inclusive way to implement social sustainability to introduce new positive economic impacts on the territory. The “Borgo +cheSostenibile” points out the necessity of preserving the heritage without freezing it into an ideal image that is detached from people’s needs. The architectural interventions might bring relevant impacts on the inner territories, producing quality, beauty, innovation, inclusion, accessibility, and in general creating more opportunities to become the promoters of a “new aesthetics of sharing” [67].

6.3. Limits: The Need to Act

In the last days of writing this article, the focus area of the Appennino Basso Pesarese Anconetano was hit by a disastrous flood event that severely impacted many municipalities and involved human losses and damages to the places [68]. Earthquakes and floods can cause enormous historical and cultural losses, which devastate local communities, as tragically shown in the recent event. Our exploration highlighted several important themes connected to the risk of abandonment and the possibilities of reactivation of built heritage in the future. Yet, the hydrogeological and seismic risks—which are important amplification factors for other risks in central Appennine—were slightly overlooked. Still, two of the research’s design explorations focused on two industrial heritage sites that were affected the most by September floods—the wheat mill with the market square in Cantiano and the ex-pasta factory in Sassoferrato. Both designs envisaged an overall rethinking of the riversides to mitigate risks, while working at the territorial and landscape scale to prevent from such events.

Research limits can be recognized in the scarce timeliness and reduced capacity to directly influence policies. Even if issues are raised, the research should be more effectively and rapidly translated into actions and should be more prompt to intercept funding and resources for intervention. Also, municipalities and local institutions, which lack means and competences to address such complex instances, should be more solidly supported by national governments in actuating long-term strategies to protect their territories. In this sense, the role of ‘research by design’ is crucial to sensitize and to propose feasible solutions. Researchers are too often perceived as distant actors and not, as they should be, as indispensable allies in the goal to reach a higher resilience for these contexts.

6.4. Outlook: Towards Territorial Enhancement

Especially in times of crisis, there is the need to rethink the structures, the tools, and the governance models to allow a quicker intervention on territories and spaces to generate new metabolisms. This article tried to investigate the drivers of change in the Appennino Basso Pesarese Anconetano to disclose its adaptation strength and to hypothesize potential actions for the reactivation of its built heritage. A renewed reading of this marginal context was portrayed that evidenced risks, values, and potentials, while focusing on relevant aspects. This methodological approach can be transferred to similar contexts. The observed dynamics of change and reactivation of built heritage and the territorial and social capital that the area can offer should be the basis for future strategic steps, together with the necessary protection measures against environmental risks.

The research outlook entails the further elaboration of the results of the “Co-design” workshop that already took place in the area, as well as the implementation of the final “Co-visioning” phase to establish stronger networking with local institutions and communities and to together envisage future branding and transformation strategies for the region. The “spaces of possibilities” [67], a resource detected in the pool of abandoned built heritage, will be further investigated and reactivated as an incubator of innovative strategies towards territorial enhancement.

Author Contributions

This paper is to be attributed in equal parts to the three authors (M.F., M.G.D.B. and C.R.), who have collaboratively contributed to its conceptualization, methodology, investigation, and writing. Conceptualization, M.F., M.G.D.B. and C.R.; Methodology, M.F., M.G.D.B. and C.R.; Data curation, M.F., M.G.D.B. and C.R.; writing—original draft preparation, review and editing: all sections M.F., M.G.D.B. and C.R., except Section 5.4, M.F.; visualization, M.G.D.B. and C.R; supervision, M.F.; project administration, M.F.; funding acquisition, M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

“B4R Branding4Resilience. Tourism infrastructure as a tool for the enhancement of small villages through resilient communities and new open habitats” (Project number: 201735N7HP) is a research project of relevant national interest (PRIN 2017-Youth Line) funded by the Ministry of University and Research (MUR) (Italy) for the three-year period 2020–2023. The project is coordinated by the Università Politecnica delle Marche, with Principal Investigator Prof. Arch. Maddalena Ferretti, and involves as partners the Università degli Studi di Palermo (Local Coordinator Prof. Arch. Barbara Lino), the Università degli Studi di Trento (Local Coordinator Prof. Arch. Sara Favargiotti), and the Politecnico di Torino (Local Coordinator Prof. Arch. Diana Rolando).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval is not required for the present study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are derived from on field research and resources available in the public domain. Data sources analyzed during the study are: Open Data Aree Interne (2014–20), Istat (2011–2019), Grafo della Viabilità Regione Marche (2011), Geoportale Nazionale (2020), Tuttitalia.it (2019), Tinitaly (2017), CTR Regione Marche (1999–2000), Corine Land Cover (2018), Rete Natura 2000 Regione Marche (2016), Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali (2013), Rete Ecologica Marche (2020), Sistema Informativo Territoriale Unione Montana Catria e Nerone (2020), Servizio WMS Regione Marche (2020), Carta geologica Regione Marche (2000), Catasto Regionale delle Attività Estrattive (1997), Atlante Consumo del Suolo Regione Marche (2016), Catasto dei sentieri Regione Marche (2010), Reticolo Idrografico Regione Marche (2007), Carta geologica Regione Marche (2000), ARPAMarche (2013–17), Piano Regionale per la bonifica delle acque inquinate Regione Marche (2006), Marche Outdoor (2020), EscursionismoperPassione (2020), Government Open Data Regione Marche (2020), ScuolaInChiaro.it (2019), viamichelin.it (2021), AGCOM Autorità per le garanzie nelle comunicazioni (2020), Piano Strategico Banda Ultra Larga (2021), Opensignal.com (2021), Agenzia del Demanio (2018), Government Open Data Regione Marche (2020), Sistema Informativo Statistico Regione Marche (2017–19), ViviMarche (2020), Osservatorio Regionale delle politiche sociali della Regione Marche (2009–19), TuttItalia.it (2020), OpenStreetMap (2021), Skirestort.it (2021), Coni (2018), Open Data Camera di Commercio delle Marche su dati InfoCamere (2019), Catasto Regionale delle Attività Estrattive (1997), Registro Imprese (2019), Carta dei Distretti Industriali della Regione Marche (2009), Piano Paesistico Ambientale Regionale delle Marche (1989), Preliminare di Piano Regionale (2009), Piano Territoriale di Coordinamento Provincia Pesaro-Urbino (2000), Piano Territoriale di Coordinamento Provincia Ancona (2003), Piano Regolatore Generale Acqualagna (2018), Piano Regolatore Generale Apecchio (2005), Piano Regolatore Generale Arcevia (2005), Piano Regolatore Generale Cagli (2001), Piano Regolatore Generale Cantiano (2003), Piano Regolatore Generale Frontone (2009), Piano Regolatore Generale Piobbico (2009), Piano Regolatore Generale Sassoferrato (2006), Piano Regolatore Generale Serra Sant’Abbondio (2004), Openbilanci.it (2016–19), Opencoesione.gov.it (2014–20), Sito Unione Montana Esino Frasassi (2020), Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali (2018), PSR Marche 2014–20 (2014), Contratti di Fiume Regione Marche (2016), PIL GAL Colli Esini-San Vicino (2014–20), PIL GAL Montefeltro (2014–20), PIL GAL Flaminia Cesano (2014–20), Bandi ‘Case a 1 euro’ Comune di Cantiano (2020), Distretto Culturale Evoluto delle Marche (2018), Piani di Gestione della Rete 2000 Regione Marche (2015), Consiglio Regionale Regione Marche (2013), Unione Montana Esino e Frasassi (2009), Regione Marche (2018), Pagine Gialle (2021), A.S.C. del Catria (2021), Fondazione MeditSilva (2021), Coldiretti (2020), and dialogues with local actors and stakeholders (2020–22).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the B4R researchers for sharing and energetically supporting the B4R project activities and for the insightful discussions and specific advice on the Marche focus area. Also, the authors would like to thank local actors and stakeholders involved in the “Exploration” phase, as well as the students of the Università Politecnica delle Marche who enthusiastically supported the research activities and participated in the B4R Thesis Laboratory supervised by Maddalena Ferretti and co-supervised by Caterina Rigo and Maria Giada Di Baldassarre.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- De Luca, C.; Tondelli, S.; Åberg, H.E. The COVID-19 pandemic effects in rural areas. TeMA J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2020, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Long-Term Vision for Rural Areas. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_21_3162 (accessed on 26 November 2021).

- Barca, F.; Casavola, P.; Lucatelli, S. (Eds.) Strategia nazionale per le Aree interne: Definizione, Obiettivi, Strumenti e Governance. Materiali Uval. 2014; Volume 31. Available online: https://www.agenziacoesione.gov.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/MUVAL_31_Aree_interne.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- De Vita, G.; Marchigiani, E.; Perrone, C. Sui margini: Una mappatura di aree interne e dintorni. BDC Bollettino Del Centro Calza Bini 2021, 21, 183–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotondo, F.; Marinelli, G.; Domenella, L. Strategia nazionale delle aree interne e programmi straordinari di ricostruzione post sisma 2016: Una convergenza per rigenerare i territori fragili e marginalizzati dell’appennino centrale. BDC Bollettino Del Centro Calza Bini 2021, 21, 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Network for Rural Development. Rural Responses to the COVID-19 Crisis. The European Network for Rural Development (EN–D)—European Commission. 9 April 2020. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/rural-responses-covid-19-crisis_en (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Giovannini, E.; Benczur, P.; Campolongo, F.; Cariboni, J.; Manca, A.R. Time for Transformative Resilience: The COVID-19 Emergency; EU Publication: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, J.; Carta, M.; Ferretti, M.; Lino, B. (Eds.) Dynamics of Periphery. Atlas for Emerging Creative Resilient Habitats; Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Egusquiza, A.; Zubiaga, M.; Gandini, A.; de Luca, C.; Tondelli, S. Systemic Innovation Areas for Heritage-Led Rural Regeneration: A Multilevel Repository of Best Practices. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, J.; Carta, M.; Hartmann, S.; Glanz, J. (Eds.) Creative Heritage; Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Carta, M. (Ed.) Patrimonio e Creatività. Agrigento, La Valle e il Parco; LIStLab: Rovereto, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- James Corner Interview. Available online: https://ilgiornaledellarchitettura.com/2020/10/06/james-corner-interview/ (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Bocchi, R. Progetto di nuovi cicli di vita per i territori italiani del XXI secolo. In Recycle Italy. Atlante; Fabian, L., Munarin, S., Eds.; LetteraVentidue: Siracusa, Italy, 2017; pp. 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zanotto, F. Circular Architecture. A Design Ideology; LetteraVentidue: Siracusa, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Viola, S. Built Heritage Repurposing and Communities Engagement: Symbiosis, Enabling Processes, Key Challenges. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, A. I territori fragili di fronte al COVID. Scienze del territorio. Rivista di Studi Territorialisti 2020, Abitare il Territorio al tempo del COVID. 2020, pp. 169–176. Available online: https://oajournals.fupress.net/index.php/sdt/article/view/12352 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Fenu, N. (Ed.) Lezioni per le aree interne. In Aree Interne e COVID; LetteraVentidue: Siracusa, Italy, 2020; pp. 104–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti, M.; Favargiotti, S.; Lino, B.; Rolando, D. Branding4Resilience: Explorative and Collaborative Approaches for Inner Territories. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Eurostat Regional Yearbook 2020; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-statistical-books/-/ks-ha-20-001 (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Gubert, R. Il mutamento sociale nell’area montana: Alcune riflessioni. In Territorio e Comunità. Il Mutamento Sociale Nell’area Montana; Demarchi, F., Gubert, R., Staluppi, G., Eds.; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 1983; pp. 147–170. [Google Scholar]

- ESPON. ESCAPE European Shrinking Rural Areas: Challenges, Actions and Perspectives for Territorial Governance. Final Report—Annex 2 Measuring, Mapping and Classifying Simple and Complex Shrinking. 2020. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/ESPON%20ESCAPE%20Final%20Report%20Annex%2002%20-%20Measuring%20mapping%20and%20classifying.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Lanzani, A.; Curci, F. Le Italie in Contrazione, Tra Crisi e Opportunità. In Riabitare l‘Italia. Le Aree Interne tra Abbandoni e Riconquiste; De Rossi, A., Ed.; Progetti Donzellli: Roma, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli, L. L’Italia è Bella Dentro. Storie di Resilienza, Innovazione e Ritorno Nelle Aree Interne; Altreconomia: Milano, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- De Rossi, A. Riabitare l‘Italia. Le Aree Interne tra Abbandoni e Riconquiste; Progetti Donzellli: Roma, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cucinella, M. (Ed.) Arcipelago Italia. Progetti per il Futuro dei Territori Interni del Paese. Padiglione Italia alla Biennale Architettura; Quodlibet: Macerata, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Marchigiani, E.; Perrone, C.; De Vita, G.E. Oltre il Covid, politiche ecologiche territoriali per aree interne e dintorni. Uno sguardo in-between su territori marginali e fragili, verso nuovi progetti di coesione. In Working Papers. Rivista Online di Urban@it; 2020; Volume 1, pp. 1–9. Available online: https://www.urbanit.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/BP_Marchiggiani_Perrone_DeVita.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2021).

- van den Heuvel, D.; Martens, J.; Sanz, M. Habitat. Ecology Thinking in Architecture; nai010 publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, M. Habitat 5.0. L’architettura nel Lungo Presente; Skira: Losanna, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rigo, C. Slow-Living Habitats. Visioni e Scenari per una Riconnessione Degli Spazi Abitati nei Territori Lenti della Regione Marche. Ph.D. Thesis, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Ancona, Italy, 22 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, C.; Ishikawa, S.; Silverstein, M. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Constructions; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Lancerini, E.; Lanzani, A.; Granata, E. Territori Lenti. Territorio 2005, 34, 9–69. [Google Scholar]

- Carta, M. Futuro. Politiche per un Diverso Presente; Rubbettino: Soveria Mannelli, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Heijman, W.; Hagelaar, G.; van der Heide, M. Rural Resilience as a New Development Concept. In EU Bioeconomy Economics and Policies: Volume II; Dries, L., Heijman, W., Jongeneel, R., Purnhagen, K., Wesseler, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Baldassarre, M.G. Designing Resilience: Trans-scalar Co-design Strategies for Resilient Habitats. In Cosmopolitan Habitat. A Research Agenda for Urban Resilience; Schroeder, J., Carta, M., Contato, A., Scaffidi, F., Eds.; Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2021; pp. 252–257. [Google Scholar]

- Lerch, D. The Community Resilience Reader. Essential Resources for an Era of Upheaval; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- De Carlo, G. L’architettura della Partecipazione; Quodlibet: Macerata, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Colucci, A.; Cottino, P. (Eds.) Resilienza tra Territorio e Comunità. Approcci, strategie, temi e casi; Fondazione Cariplo: Milano, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rieniets, T. What about the other 98%. In Creative Heritage; Schroder, J., Carta, M., Hartmann, S., Eds.; Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2018; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Lesh, J. Place and Heritage Conservation. In The Routledge Handbook of Place; Edensor, T., Kalandides, A., Kothari, U., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Buthke, J.; Larsen, N.M.; Ostendeld Pedersen, S.; Bundgaard, C. Adaptive Reuse of Architectural Heritage. In Impact: Design With All Senses. Proceedings of the Design Modelling Symposium, Berlin 2019; Gengnagel, C., Baverel, O., Burry, J., Ramsgaard Thomsen, M., Weinzierl, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bassindale, J. Adaptive Reuse as a Design Process. In Architectural Regeneration; Orbasli, A., Vellinga, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grecchi, M. Industrial Heritage: Sustainable Adaptive Reuse. In Building Renovation. How to Retrofit and Reuse Existing Buildings to Save Energy and Respond to New Needs; Grecchi, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Inti, I. Pianificazione Aperta. Disegnare e Attivare Processi di Rigenerazione Territoriale in Italia; LetteraVentidue: Siracusa, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation, ARUP. Circular Economy in Cities: Project Guide, Ellen MacArthur Foundation Pubblications. 2019. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/CE-in-Cities-Project-Guide_Mar19.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Carta, M. The Augmented City. A Paradigm Shift; List-Lab: Trento, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Feldhusen, S. Knowledge as the known—On the dialogue between theory and the work. In Designing Knowledge; Weidinger, J., Ed.; Technische Universität Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Roggema, R. Research by Design: Proposition for a Methodological Approach. Urban Sci. 2016, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzyk, K. Wicked Problems in Architectural Research: The Role of Research by Design. ARENA J. Archit. Res. 2022, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, J. Urbanism and Architecture in Regiobranding. In Scenarios and Patterns for Regiobranding; Schröder, J., Ferretti, M., Eds.; Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rolando, D.; Rebaudengo, M.; Barreca, A. Exploring the resilience of inner areas: A cross-dimensional approach to bring out territorial potentials. In Proceedings of the Symposium New Metropolitan Perspectives, Reggio Calabria, Italy, 25–27 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rolando, D.; Rebaudengo, M.; Barreca, A. Managing Knowledge to Enhance Fragile Territories: Resilient Strategies for the Alta Valsesia Area in Italy. In Proceedings of the 17th International Forum on Knowledge Asset Dynamics (IFKAD) “Knowledge Drivers for Resilience and Transformation”, Lugano, Switzerland, 20–22 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wittek, R. Stakeholder Analysis. In Humanitarian Crises, Intervention and Security: A Framework for Evidencebased Programming; Heyse, L., Zwitter, A., Wittek, R., Herman, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Martinuzzi, C.; Lahoud, C. Public Space Site-Specific Assessment Guidelines to Achieve Quality Public Spaces at Neighbourhood Level; United Nations Human Settlements Programme, UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Barbera, F.; Parisi, T. Innovatori Sociali. La Sindrome di Prometeo nell’Italia che Cambia; Il mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, B.B. Rural marginalization and the role of social innovation; A turn towards nexogenous development and rural reconnection. Sociol. Rural. 2016, 56, 552–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrosio, G.; Moro, G.; Zabatino, A. Cittadinanza attiva e partecipazione. In Riabitare l‘Italia. Le Aree Interne tra Abbandoni e Riconquiste; De Rossi, A., Ed.; Progetti Donzellli: Roma, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Carrosio, G.; Faccini, A. Le Mappe della cittadinanza nelle aree interne. In Riabitare l‘Italia. Le Aree Interne tra Abbandoni e Riconquiste; De Rossi, A., Ed.; Progetti Donzellli: Roma, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Carrosio, G. I margini al Centro. L’Italia Delle Aree Interne tra Fragilità e Innovazione; Donzelli Editore: Roma, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Babchuk, N. The Role of the Researcher as Participant Observer and Participant-as-Observer in the Field Situation. Hum. Organ. 1962, 21, 225–228. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/44124440 (accessed on 1 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- Chovgrani, C.; Cieślikowska, M.; Odyniec, K. Challenges of field research. Between involved participant and outside observer. Int. J. Pedagog. Innov. New Technol. 2019, 6, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghirri, L. Lezioni di Fotografia; Quodlibet: Macerata, Italy, 2010; pp. 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Haven, K. Story Proof: The Science behind the Startling Power of Story; Libraries Unlimited: Westport, Connecticut, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Di Baldassarre, M.G. Designing Resilience. Trans-Scalar Architecture for Marginal Habitats of Marche Region. Ph.D. Thesis, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Ancona, Italy, 21 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Regiobranding. Branding von Stadt-Land-Regionen durch Kulturlandschaftscharakteristika. Available online: www.regiobranding.de (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Ferretti, M.; Favargiotti, S.; Lino, B.; Rolando, D. B4R Branding4Resilience. Tourist infrastructure as a tool to enhance small villages by drawing resilient communities and new open habitats. In Le Politiche Regionali, la Coesione, le Aree Interne e Marginali. Proceedings of the Atti della XXIII Conferenza Nazionale SIU DOWNSCALING, RIGHTSIZING. Contrazione Demografica e Riorganizzazione Spaziale, Torino, Italy, 17–18 June 2021; Brunetta, G., Corrado, F., Marchigiani, E., Marson, A., Servillo, L., Eds.; Planum Publisher e Società Italiana degli Urbanisti: Roma-Milano, Italy, 2021; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Barbera, F.; Cersosimo, D.; De Rossi, A. Contro i Borghi. Il Belpaese che Dimentica i Paesi; Donzelli: Roma-Milano, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti, M.; Di Baldassarre, M.G.; Rigo, C.; Di Leo, B. Borgo +che sostenibile. Rigenerare gli habitat marginali dell’area interne marchigiana attraverso l’architettura, il patrimonio e la comunità. Ananke 2022. in progress. [Google Scholar]

- Rapporto Evento della Protezione Civile Relativo All’alluvione. 2022. Available online: https://www.regione.marche.it/portals/0/Protezione_Civile/Manuali%20e%20Studi/Rapporto_Evento_preliminare_20220915.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).