4.1. Key Factors of Organizational Innovation of UASs

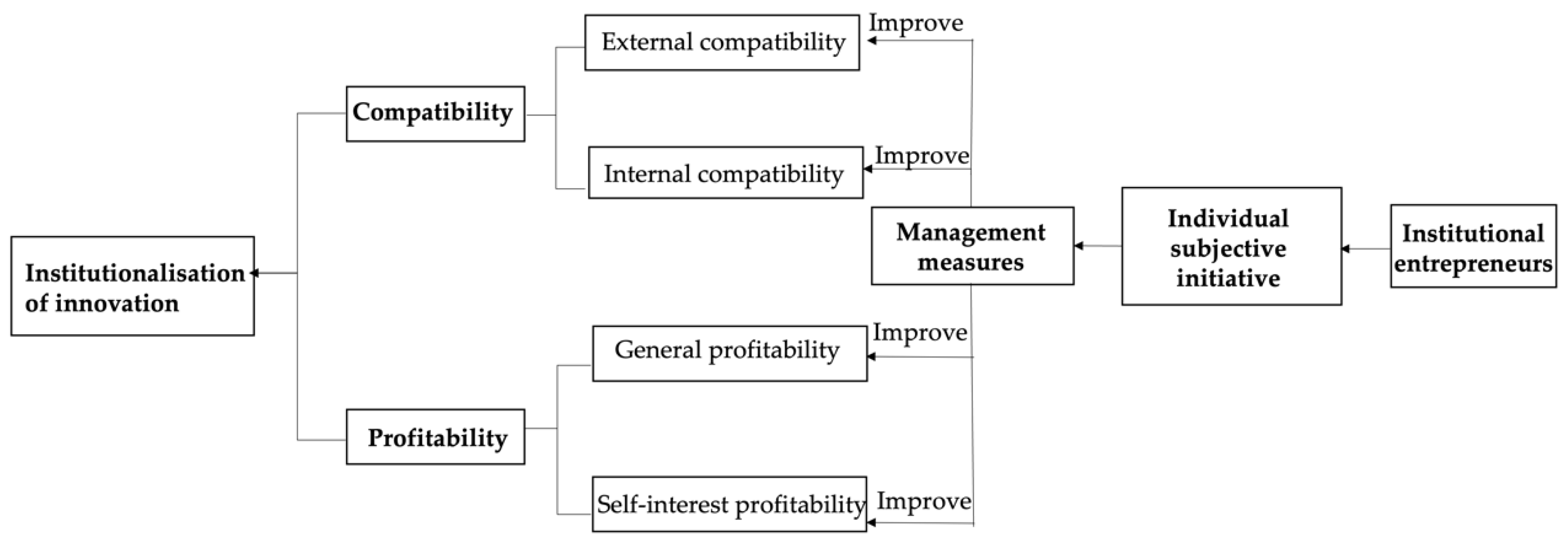

According to the analytical framework, the most crucial factors affecting the organizational innovation process fall into the categories of external compatibility, internal compatibility, general profitability, and self-interest profitability. In this study, external compatibility focused on the extent to which the mission of a UAS conformed to national policies, the legal context in the province and the local city, and regional industrial demands. Internal compatibility examined the extent to which the practice of a UAS was well-matched with both its administrative structure and institutional cultures. General profitability concerned the extent to which the university gained benefits from engaging in the innovation system, as well as the profit-making for regions and industries. Self-interest profitability considered the extent to which the participators in the UAS, who engaged in the innovative activities, gained tangible and intangible benefits. The key participators included university leaders, teachers, and local industry experts. Finally, the four factors with specific indicators determined the level of organizational innovation used by the UAS to engage in the regional innovation system.

Table 2 presents a summary of the empirical results related to the three UAS case studies.

The three UAS case studies had to comply with national and provincial policies to promote and upgrade their institutional organization and embrace the demands of regional industries. However, unlike the UASs in Germany, the UASs located in less-developed areas of China could barely access adequate funds and resources from local government and small- and middle-sized companies. Furthermore, their internal institutional administrations were struggling to survive by swaying between “conventions” or “innovations”, and the planning and development of disciplines were often trapped in a struggle between “practical applications” or “theoretical research”. In these circumstances, it was a win–win situation for UASs to closely collaborate with local government and industries with the aim of drawing on diverse resources, jointly training applied talents, and conducting applied science research. In the long term, the regional industries could gain more capable labor force from the UASs, which would further enhance research and development activities. In addition, the benefits received by different stakeholders had different weights. The intentions of university leaders to drive organizational innovation forward varied from person to person. Teachers generally benefited from enriched course cases, internship offers, and perspectives and skills obtained from industries, and were more likely to gain promotions and incentive remuneration. By contrast, industry experts had to “do much but get little” when coaching students, without much payment or honors in the two public case UASs (KU, DU). This partly resulted in a lack of motivation for deeper cooperation from the industrial side.

4.1.1. External Compatibility

The central government of China issued a series of national policies to support the development of UASs in 2014. Their principal features are: (1) highlighting the importance of UASs in the national higher education system; (2) emphasizing the vital functions of UASs in regional development; (3) encouraging university–industry collaboration in teaching and learning for UASs. The Modern Vocational Education System Construction Plan (2014–2020), issued in 2014, suggested that the Central and Western local governments devoted themselves to raising funds for promoting regional development through the efforts of UASs. The Relevant Work on Supporting the Development of UASs, released in 2019, proposed 100-million-yuan of financial support for each UAS recommended by the province, for a total quota of 100 UASs. However, the welfare embedded in these national policies predominantly flowed to developed areas, which held greater authority than their less-developed counterparts. The national policies are expected to provide equal financial support to UASs across different regions. However, the financial pressures transferred to local governments, which resulted in a “Matthew Effect” of making “the strong stronger and the weak weaker” among UASs (BU02, DU04). Therefore, the three UAS case studies, on the one hand, conformed to the national trend of vigorously developing UASs, but were, on the other hand, subjected to a lack of special funds or policies supporting less-developed areas from the central government. The financial obstacles encountered by BU were even worse than the other two case studies, due to its private nature, which meant the government was not obligated to financially support it.

The Yunnan provincial government was responsive to the national initiatives related to developing local UASs and cultivating local applied talents. It has issued related policies, such as the Outline of the National Plan for Medium- and Long-Term Education Reform and Development, 2010–2020 (MOE, 2010) and the Guiding Opinions of the Ministry of Education, Development and Reform Commission, and Ministry of Finance on Guiding some Undergraduate Universities to Transform to Application-Oriented Universities (2015). These provincial policies have endeavored to encourage enterprises to engage in teaching, pedagogical innovation, curriculum development, and textbook co-authoring with HEIs. Along with a series of guidelines created by the Ministry of Education for transforming local undergraduate universities into UASs, Yunnan Province Education Department (YPED) piloted the reform of nine local universities to serve the development of the regional economy from 2014 to 2016. Under such policy guidance, in 2017, six UASs were confirmed as Applied Undergraduate Talent Training Demonstration Institutions, including KU and BU. Subsequently, DU was also selected as a demonstration UAS in 2019. As the only private UAS in the first batch of demonstration institutions, BU presented outstanding achievements in entrepreneurial education. However, tensions existed between the new initiatives and old standards. For example, the standard curriculum quality assessment for HEIs did not match the demands of application-oriented teaching in the UASs. Furthermore, plunging into long-term budget deficit, the provincial government struggled to meet its promised funds for the transformation of UASs through activities such as constructing smart classrooms or project-based teaching and learning, especially for non-capital cities (BU01, DU01, DU03, DU04).

As the gateway to Southeast Asia, Yunnan Province is a pivotal area in the national Belt-and-Road development strategy. It covers an area of 394,100 square kilometers, and 88.64% of this area is mountain plateau terrain. Thus, it is rich in natural resources of animals, plants, non-ferrous metals, and tourist attractions. As a result of the geographical features of the terrain, its key industries are concentrated in modern agriculture on the plateau, tourism and culture, biomedicine and health, new materials, modern logistics, food, and consumer goods manufacturing. The UAS case studies consciously designed their distribution of disciplines according to such regional industrial demands and trained relevant applied talents (KU01, BU01, DU01). For example, DU established a triple discipline cluster of “biomedicine, minority culture, and ecological environment” for regional advancement. Its applied science research on plateau-based modern agriculture and phytoecology not only served the industries of west Yunnan, but also radiated throughout other countries in South Asia, such as India, Laos, and Nepal (DU17). KU established professional education in tourism, chemical engineering, agriculture, and life sciences to satisfy the regional demands for human resources. Moreover, BU organized an investigation team to visit local companies regularly to collect their feedback on labor demands and, based on this feedback, adjusted its strategy of applied talent training. Nevertheless, rapid changes in the industries brought uncertainty about the direction in cultivating applied talents tailored to industrial needs (BU01, KU01).

4.1.2. Internal Compatibility

Internal compatibility examined whether the management practices of UASs were consistent with their administrative structures and institutional cultures. The strategical goals of the UAS case studies all concentrated on cultivating high-quality applied talents, enhancing applied science research, serving regional industries and societies, and cooperating with South and Southeast Asia. Nonetheless, there were vivid distinctions among the unique characteristics of the UAS case study institutional cultures (

Table 3). KU and DU were traditional public universities that had experienced several mergers. DU was the only university that was far away from the capital city but possessed the right to grant master’s and doctoral (2021) degrees in west Yunnan. Inheriting characteristics from previous colleges, and functioning as a synthesis of applied and research universities, both KU and DU attached great importance to applied science research. Due to their public nature, KU and DU had an administrative structure led by the Communist Party. Moreover, KU managed the university using five systems, namely an organizational leadership system, an academic governance system, a teaching and research organization, a democratic supervision system, and a counseling system. As Zhang argued, the decision-making system, execution system, supervision system, and common management system jointly worked toward the coordinated operation of university internal governance in Chinese public universities [

48]. In a sense, the administrative structures of KU and DU were compatible with their institutional cultures and strategic goals as public universities. By contrast, BU was a newly established private university, funded by entrepreneurs who inserted into the institution a gene of risk-taking, innovation, and entrepreneurial spirit. Moreover, its management team was inclined to accept new patterns of governance and pursue working efficiency (BU01, BU05). BU adopted an adjustable private administrative structure with a board of directors, a president, an academic board, a teaching committee, a student affairs committee, and executive agencies. In particular, the student affairs committee was separate from the executive agencies, which showed extraordinary attention to the students.

However, organizational innovation might arouse contradictory conflicts between the “old institutional system” and “new reform conceptions”. KU was a typical public university that was not fueled with sufficient incentives for teachers to reform. With the inborn advantages of being located in the capital city, it was placed in a comfort zone that encouraged it to follow the previous system. One interviewee said, “Indeed, it is extremely difficult for functional departments to drive forward the reform among teachers. It would be unsuccessful unless to take forceful measures. It also worked when the university delegated the authority of resource allocation, personnel appointment and assessment to the department” (KU01). Furthermore, one obstacle KU faced in promoting collaboration with enterprises was its fixed teaching arrangements. The invited speakers from companies needed to follow the exact teaching time for a course. regardless of their work schedules (KU03). Therefore, flexibility was essential to KU’s ability to undertake organizational innovation. DU was another case with a rigid mechanism for managing and allocating funds. Its performance priority was to stimulate the faculty to apply for national research programs, instead of conducting joint research with local enterprises. Elder faculty members who had merged from vocational colleges were not competent in research (DU04). For the faculty members, it was extremely difficult to successfully apply for competitive projects with limited support for resources and equipment. Even if they received project funds, only a very small amount would be allocated to individuals (DU01). This administrative mechanism was not effective in enabling the faculty to participate in regional innovation. The institutional challenges of BU originated from its survival pressure as a private university. For example, it was still difficult to increase the student enrollment quota from the provincial government, despite their great efforts to attract good students (BU03). In addition, many senior faculty members or PhD members were unwilling to join a private university because they were worried about instability in their career path (BU04). This resulted in a shortage of highly educated and experienced faculty members to support BU’s organizational innovation.

4.1.3. General Profitability

As active innovators, UASs expected to gain generous benefits from participating in the regional innovation system and furthering its development. Firstly, this participation was a path toward discovering how to develop a unique and remarkable university in a certain area. This was conducive to UASs’ winning a good social reputation and expanding their presence and impact. It was even more important for a private university to acquire social recognition, which determined the effectiveness of its student recruitment. Secondly, as rewards for collaboration with enterprises, UASs established internship bases for students and obtained funds, equipment, experts, and skill training. Co-teaching by professional teachers and industry experts enhanced both the theoretical knowledge and practical skills of students, thereby improving their competitiveness in employment. Thirdly, the UASs’ networks for raising funds were further broadened through jointly applied science research with government and industries. As the UASs were located in less-developed regions, a lack of funds became the biggest obstacle to their development; any initiatives that were effective at receiving funds were considered worthwhile. However, to achieve these ambitions, the UASs needed to afford the cost of organizational management and innovation, including top-level design, administrative regulations, and working groups. This required investing in sufficient human resources and adequate funding. In addition, internally, they attempted to reconcile the contradiction between conservative organizational cultures and new reform measures. Externally, they sought opportunities to connect, integrate, and cooperate with different stakeholders in the regional innovation system.

The cooperation between government–UASs–enterprises created continuous energy for regional innovation, as well as for industrial development. For less-developed areas, this cooperation was the most effective way to cultivate capable, suitable, and retainable applied talents for local industries. Well-operated cooperation established a brand for the local city and gradually increased the ability of local enterprises to raise money. Nevertheless, the cost for stakeholders varied. Local government functioned as a convenor that could gather different stakeholders, including industrial associations, universities, and companies. It was able to unveil relevant policies, provide an exchange platform, and create a favorable environment. Similarly, the industrial associations served as bridges that could link enterprises with UASs by regularly organizing interchange activities and conferences. In contrast, companies were burdened with the most expensive costs. For preliminary cooperation, companies invested in a site and staff to train students in practical skills. For deeper cooperation with universities, the cost frequently increased. For example, a joint laboratory required purchasing equipment, inputting operational funds, and designating experienced experts to work out training plans, design courses, and instruct operations on campus. Therefore, arousing the enthusiasm of local companies to invest labor and financial resources into a regional innovation system, when there was no immediate payoff for the companies, was a critical issue.

4.1.4. Self-Interest Profitability

Self-interest profitability can mainly be embodied in university leaders, teachers, and industry experts. As the key organizational entrepreneurs, university leaders in this study benefited from reform achievements by gaining recognition and promotion. They also obtained a sense of challenge and accomplishment from overcoming difficulties (BU01). With a more flexible promotion system, BU promoted and rewarded young leaders who contributed to crucial decision-making (BU05). Even in public universities, a good working reputation was conducive to further promotion within the university or among other universities. Moreover, communication with government, industries, and companies was an effective way for university leaders to establish well-connected interpersonal networks. Therefore, it was beneficial to the management team to promote the integration of organizational innovation with the regional innovation system. However, it is worth noting that this also brought great stress to university leaders. In particular, at the private university, there was a sense of crisis related to institutional survival- leaders were worried the university might close (BU03, BU06). Sometimes, the university leaders might face huge practical difficulties in promoting reforms and innovations. This energy-consuming process required their continual inner drive, work enthusiasm, and social mission.

Teachers at UASs gained both direct and indirect benefits from the process of integrating the UASs into the regional innovation system. The most direct benefits were the rewards they received from the university to encourage them to collaborate with local companies in teaching and learning. These rewards could be an incentive bonus, such as the doubled course remuneration provided by BU, and the counterpart funding of national research programs at DU. Collaborative funds for applied science research offered by local companies were also significant funding sources for teachers at UASs. However, in less-developed areas, companies seldom had such solid capital resources. Another direct benefit was career development and promotion of teachers with a “double qualified” title gained. BU attempted to have varied subsidy and reward standards corresponding with the levels of elementary, intermediate, and advanced “double qualified” teachers. The other two UAS case studies also appreciated the achievements of “double qualified” teachers who worked to integrate with regional industries. In contrast, indirect benefits were improvements in the capabilities and skills of teachers to collaborate with local companies. This collaboration could increase their practical experience and their insight into updating industry frontiers. Furthermore, teachers could borrow industry perspectives and cases for use in their course content to refresh their teaching. Communication with local companies and industry experts also provided a solid foundation for further joint applied sciences research. However, integration with the development of regional industries cost teachers tremendous amounts of energy and time. Under heavy pressure to do both teaching and research, teachers sometimes preferred to finish only basic tasks, especially the “visible” and “profitable” research work. In this case, they placed lower priority on efforts to cooperate with local companies.

The self-interest profitability industry experts gained from cooperation with UASs depended on their personal preferences. The cooperating universities generally offered industry experts well-respected titles, such as “enterprise mentor“ or “industry leader”, but they received little monetary return, or were even expected to work for free in less-developed areas. One category of enterprise mentors comprised those who were invited by a university to give a speech or instruct courses. Such mentors could receive little payment for teaching in public universities. Compared with 80 yuan (11.44 US dollar) per hour for university teachers, these mentors could gain about 200 yuan (28.6 US dollar) per hour, but this amount was still very low and lacked any other welfare (DU01). Another kind of enterprise mentor guided students’ practical operations in their own institutions. For many of these mentors, this guidance was additional, free work they completed in order to train apprentices (DU04). The potential benefits included discovering and working with future suitable employees. Additionally, by expanding their individual influence, enterprise mentors could search for more opportunities to collaborate with teachers in applied sciences research. However, the cost for them was plenty of time and energy, as well as the adaptive cost of communication and instruction. For public universities, they might also suffer complicated hiring and auditing procedures to ensure the consistency of teaching ideas (KU01, DU01). In contrast, to attract more enterprise mentors from companies, the private university in this study provided considerable payments and flexible hiring procedures (BU03, BU04). The leaders of key company partners could participate in the governance of the university, propose their demands about talents, and select capable employees based on internships (BU09, BU11).

4.2. The Initiatives Institutional Entrepreneurs Took to Tackle Challenges

4.2.1. The University Leaders

Faced with numerous internal and external incompatibility issues, the decision-makers of the UAS case studies responded actively. The leaders of the three UAS case studies reached a unanimous consensus on cultivating applied talents to serve the regional economic development of Yunnan Province. Focusing on this concept, the UAS case studies arranged their training programs, professional settings, and enterprise cooperation around it. When they encountered difficulties, the leaders tried their best to figure out innovative solutions. For example, one of the essential problems faced by BU was that it had a majority of young teachers who lacked teaching and work experience. After realizing this problem, the president decided to hire about 380 newly retired teachers from other renowned universities to lead the young teachers in constructing course systems (BU01). These retired teachers, as academic leaders, were responsible for improving the teaching capabilities of the young teachers, building courses and disciplines, and conducting curriculum research. The extensive experience of the retired teachers was effectively used in this university to solve the capability issues of its faculty. Similarly, the management team at KU made sufficient preparations for students to build a platform of university–enterprise cooperation. As a result, its cooperation with the Kunming Institute of Food and Drug Research and Quality was quite deep and useful. Teachers and students participated in the entire production and regular testing processes of this institute. Furthermore, the leaders of DU promoted cooperation with local government and industries and held joint meetings every year to understand the needs of regional development.

The president of each university was the spiritual leader of the whole UAS. They determined the internal atmosphere, institutional culture, and campus spirit of the entire university. The principal of BU once was in charge of teaching at another public university. Therefore, he was familiar with teaching management and was able to promote a vigorous curriculum reform beginning in 2016. BU’s teaching achievements won the first and second prizes of the Yunnan Provincial Excellent Teaching Achievement Award. Moreover, its founder and chairman injected genes of risk-taking, innovation, entrepreneurship, and hard work into the university (BU05). This created an atmosphere of innovation and entrepreneurship. In competitions of innovation and entrepreneurship, 114 students won national awards and 414 students won provincial awards. The university–industry collaboration of DU also flourished under several key presidents. In 2009, DU introduced a vice president from the School of Pharmacy of Zhejiang University. He opened a new world for the integration of industry and education at this university. One way he did this was to sign training contracts with enterprises from other provinces and cities to provide students with scholarships and stipends and the other was to promote Dali Pharmaceutical to invest 1 million yuan in establishing a teaching platform. In an economically less-developed area like west Yunnan, it was indispensable to obtain principals and leaders with the perseverance, vision, and passion to implement flexible, open, and resilient concepts about the integration of industry and the regional innovation system.

4.2.2. The Middle-Level Leaders

The middle-level managers were the bridges of information transmission and decision-making execution in the UASs. They needed to clearly understand the intentions of the management decision makers, such as the concepts and development direction of the UASs. The goal of middle-level management was to implement the development goals of their universities (KU01). Moreover, the middle-level managers also needed to convey the philosophy of the UASs from the top down. One approach was to establish working groups to figure out management policies and provide a cooperative platform (BU05). Another approach was to organize workshops among teachers to discuss training purposes and methods for applied talents (DU02). These approaches might help the entire top–down system of a university to develop along one main line.

More importantly, the hierarchical design of the governance system helped with implementing various activities of university-industry collaboration in teaching and learning. Take BU as an example. Its first step was to establish a lead working group for university–industry collaboration in teaching and learning. It was composed of the president, vice presidents, and heads of each division. The main responsibilities of the lead working group included formulating university–industry integration policies and planning and approving cooperation agreements for major cooperative projects, such as setting up customized classes and industrial colleges. The second step for management was to set up an executive office of university–industry collaboration to carry out the overall planning, management, coordination, and daily work determined by the lead working group. The third step was to set up departmental working groups within each department. The dean of each department served as the person in charge, and the deputy deans, directors, and staff were team members. This cooperation and close exchange at the three working layers ensured the relatively smooth execution progress of university–industry cooperation in teaching and learning.

4.2.3. The Teachers

The teachers were the knowledge disseminators and industry practitioners who guided the applied talent training in the UASs. Relying only on textbook knowledge transfer could not meet the demand for applied talents for local industries. In contrast, combining theoretical knowledge with industry practice was conducive to integrating student training into the regional development system. Within the governance system, the evaluation of “dual-qualified” teachers complied with this vision. Under the guidance of this evaluation, teachers tended to take the initiative to cooperate with local companies to optimize courses. Communication with enterprises also helped teachers understand the development trends of their industry and thereby update their teaching content. For example, the teachers of Logistics Teaching and Research at KU established a cooperative relationship with Jingdong (JD). This university hired the general manager of JD Logistics Yunnan as an enterprise mentor who could teach on campus. The young teachers in the Center of Logistics Teaching and Research also came to this class to learn knowledge from industry (KU06). These teachers led students to join the JD training base for specific work over more than 20 days. After that, JD gave feedback to the young teachers on how to incorporate student training into industry practice. Throughout this course, the young teachers obtained teaching methods, came to understand industry frontiers, and gained experience cooperating with enterprises. Another example was one of the best courses at BU, called Flat Graph Recognition. The teacher of this course claimed that he had received four different grants totaling 165,000 yuan for university curriculum reform (BU14). With such strong support, he devoted himself to constructing this course, including producing more than 400 teaching tools and establishing an online learning platform. So far, his WeChat public platform has released more than 1600 learning resources. This platform attracted 20,000 followers, half of whom came from developed cities outside Yunnan Province, such as Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Hong Kong, and Macau. This kind of educational resource, which spread from a less-developed area to developed areas, was praiseworthy for its excellent performance.

Teachers at DU led students to participate in applied science research serving local government and industries. This university was a comprehensively developed UAS that emphasized scientific research work with regional characteristics. In the assessment of its teachers, scientific research had a greater weight than teaching (DU12, DU13). With the help of the local government, the School of Agriculture and Biological Sciences established cooperation with many local farm product enterprises (DU12). On the one hand, it built cooperative scientific research projects with these companies, aiming to solve practical problems in planting and production. On the other hand, students followed teachers to participate in the actual work and research of these companies. Such a combination of applied sciences research and practices could effectively serve the demands of these small- and medium-sized local farm product companies. Similarly, many teachers in the School of Pharmacy took undergraduates and graduate students to engage in local phytopharmacological research. This research included both purely theoretical research and the development of new drugs in enterprise applications (DU15). In addition, because of insufficient teaching support funds, teachers often took their students to walk for 6 h instead of taking a bus to the learning base on the top of a mountain. In return, this process also inspired in students hard work, perseverance, and the cherishing of learning opportunities.

4.2.4. The Students

The students in the UASs worked hard to satisfy the employment demands of regional industries. Many of them chose to study in UASs to obtain a bachelor’s degree and then find a job after graduation (BU01). After they entered the university, they studied hard and actively participated in practices to enhance their employment competitiveness. During the process of cooperative teaching between UASs and companies, the companies selected outstanding students to stay for work. The common characteristics of these selected students included working diligently and having strong hands-on ability (BU10). More importantly, they were willing to stay and work in less-developed areas instead of prosperous cities (BU11). For those small- and medium-sized companies located in less-developed areas, it was extremely important to retain practical and capable talents. For students who had an internship in a partner company, the practical experience could give them some priority in job opportunities.

A few students made efforts to obtain more vocational certificates and higher academic qualifications. Under the premise that there was no excessive financial burden for their families, about half of the students at DU took the postgraduate entrance examination (DU22). Although the exam success rate was only about 20–30%, many students applied for graduate programs within Yunnan Province. They believed that the best students should pass the postgraduate entrance examination and further continue their studies (DU25). Obtaining a higher level of academic qualifications enabled students to have a deeper understanding of their majors and find a better job (DU26). Even if they originally had had no intention to do so at the beginning, some students chose to take the postgraduate entrance examination with the encouragement of teachers and other classmates (DU24). Pursuing a higher degree also enhanced the overall capacity of students to participate in, and promote, regional development.