Relationship between the Type A Personality Concept of Time Urgency and Mothers’ Parenting Situation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Study Survey

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Characteristics

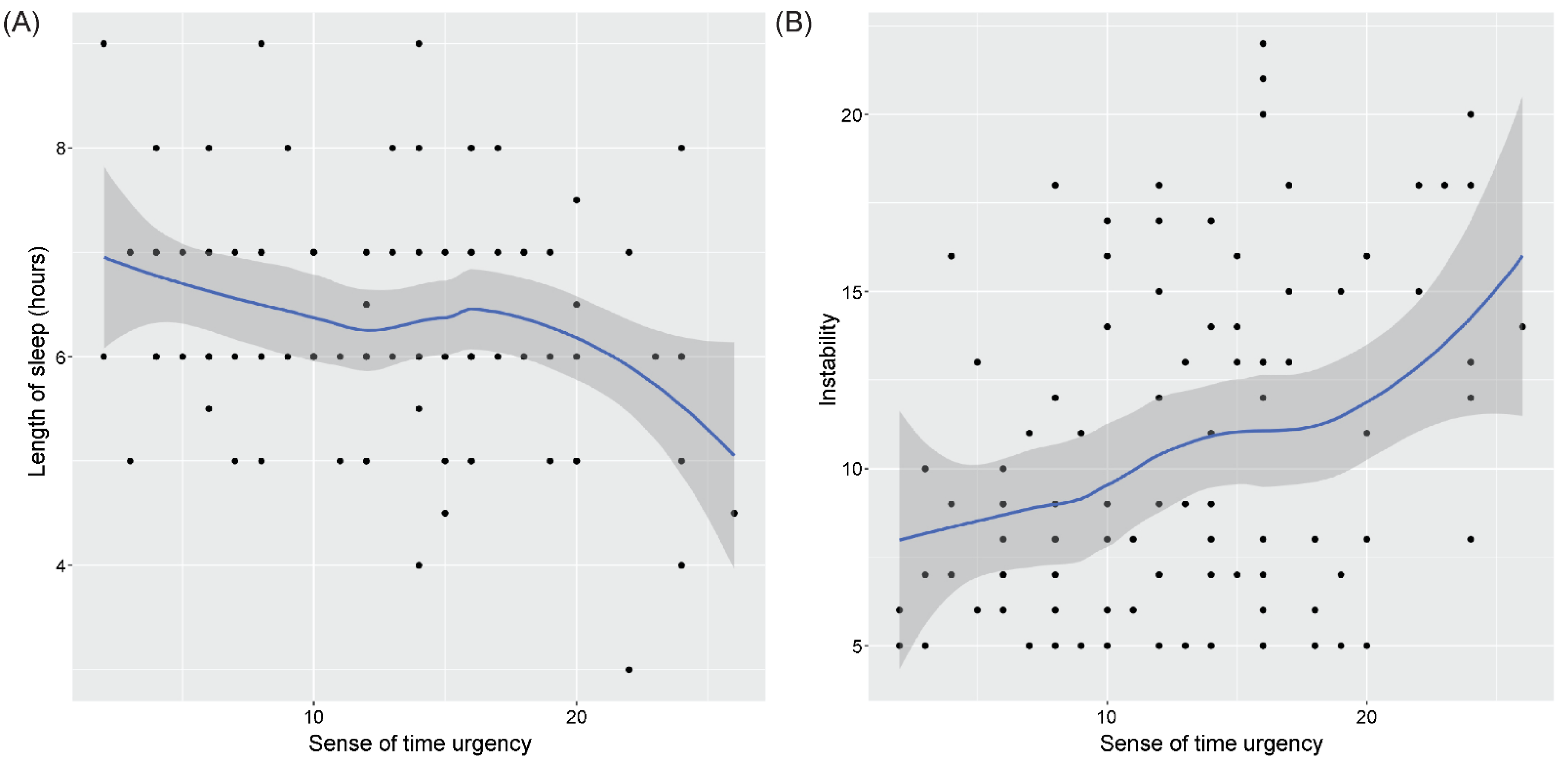

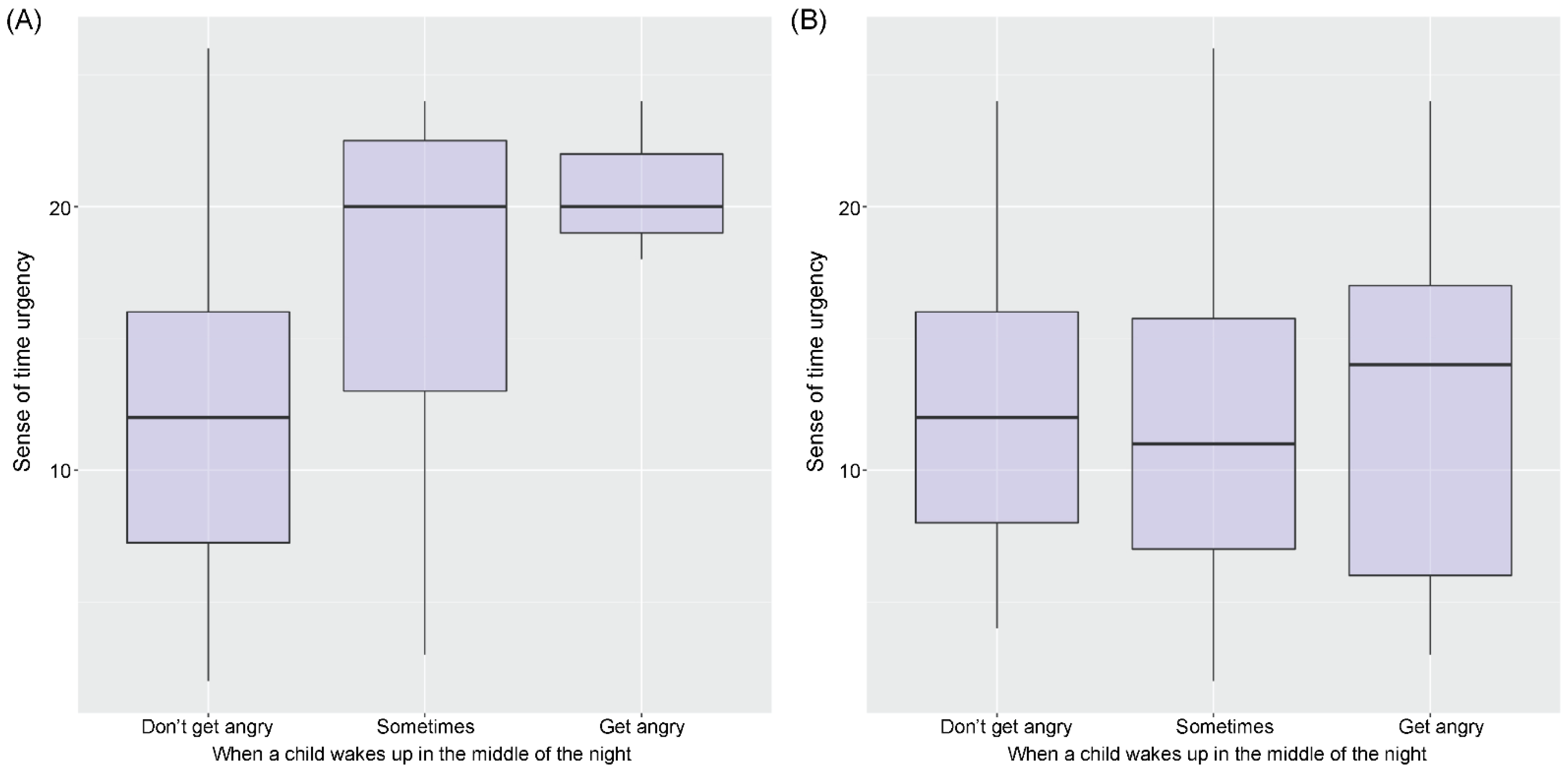

3.2. Variation of the Sense of Time Urgency Score with Respect to Other Factors

3.3. Factors Associated with Sense of Time Urgency as Revealed by Multivariable Linear Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ivancevich, J.M.; Matteson, M.T. Type A behaviour and the healthy individual. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 1988, 61 Pt 1, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Feng, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X. Bibliometric analysis of theme evolution and future research trends of the Type A personality. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2019, 150, 109507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohse, T.; Rohrmann, S.; Richard, A.; Bopp, M.; Faeh, D.; Swiss National Cohort Study Group. Type A personality and mortality: Competitiveness but not speed is associated with increased risk. Atherosclerosis 2017, 262, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šmigelskas, K.; Žemaitienė, N.; Julkunen, J.; Kauhanen, J. Type A behavior pattern is not a predictor of premature mortality. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2015, 22, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, B.D.; Chen, W.; Harville, E.W.; Bazzano, L.A. Associations between Hunter Type A/B Personality and Cardiovascular Risk Factors from Adolescence through Young Adulthood. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2017, 24, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirri, L.; Fava, G.A.; Guidi, J.; Porcelli, P.; Rafanelli, C.; Bellomo, A.; Grandi, S.; Grassi, L.; Pasquini, P.; Picardi, A.; et al. Type A behaviour: A reappraisal of its characteristics in cardiovascular disease. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2012, 66, 854–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukita, S.; Kawasaki, H.; Yamasaki, S. Does behavior pattern influence blood pressure in the current cultural context of Japan? Iran J. Public Health 2021, 50, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, R.E.; Mehta, Y.P. The big five, type A personality, and psychological well-being. Int. J. Psychol. Stud. 2018, 10, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintsa, T.; Hintsanen, M.; Jokela, M.; Pulkki-Råback, L.; Keltikangas-Järvinen, L. Divergent influence of different type A dimensions on job strain and effort-reward imbalance. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2010, 52, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do I Need to Wake My Baby? Available online: https://www.breastfeeding.asn.au/resources/wake-my-baby (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- Buddelmeyer, H.; Hamermesh, D.S.; Wooden, M. The stress cost of children on moms and dads. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2018, 109, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, K.; Kennedy, E.; Young, B. “Sometimes I Think My Frustration Is the Real Issue”: A Qualitative Study of Parents’ Experiences of Transformation after a Parenting Programme. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crnic, K.A.; Greenberg, M.T. Minor parenting stresses with young children. Child Dev. 1990, 61, 1628–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, C.M.; Green, A.J. Parenting stress and anger expression as predictors of child abuse potential. Child Abus. Negl. 1997, 21, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, L.G.; Anthony, B.J.; Glanville, D.N.; Naiman, D.Q.; Waanders, C.; Shaffer, S. The relationships between parenting stress, parenting behaviour and preschoolers’ social competence and behaviour problems in the classroom. Infant Child Dev. 2005, 14, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFreniere, P.J.; Capuano, F. Preventive intervention as means of clarifying direction of effects in socialization: Anxious-withdrawn preschoolers case. Dev. Psychopathol. 1997, 9, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rizkalla, A.N. Sense of time urgency and consumer well-being: Testing alternative causal models. In NA—Advances in Consumer Research Volume 16; Srull, T.K., Provo, U.T., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Chicago, IL, USA, 1989; pp. 180–188. [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Miyata, Y. Type A questionnaire for Japanese adults (KG’s Daily Life Questionnaire). J. Type Behav. Pattern 1992, 3, 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, T.; Matsumoto, S. Actual conditions of work, fatigue and sleep in non-employed, home-based female information technology workers with preschool children. Ind. Health 2005, 43, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venables, W.N.; Ripley, B.D. Modern Applied Statistics with S, 4th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Gómez Gil, E.; Salamero Baró, M.; Fernandez-Huerta, J.M.; Fernandez-Solá, J.M.; Fernandez-Solá, J. Relación entre el síndrome de fatiga crónica y el patrón de conducta tipo [Relationship between chronic fatigue syndrome and type A behaviour]. Med. Clin. 2009, 133, 539–541. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Orpen, C. Type A personality as a moderator of the effects of role conflict, role ambiguity and role overload on individual strain. J. Hum. Stress 1982, 8, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Terao, T.; Hoaki, N.; Goto, S.; Araki, Y.; Kohno, K.; Mizokami, Y. Type A behavior pattern: Bortner scale vs. Japanese-original questionnaires Japanese. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 142, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulack, D.; Nesca, M.; Stroud, B.M. Laboratory sleep patterns and dream content of Type A and B scoring college students. Percept. Mot. Skills 1993, 77, 216–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubo, T.; Takahashi, M.; Sato, T.; Sasaki, T.; Oka, T.; Iwasaki, K. Weekend sleep intervention for workers with habitually short sleep periods. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2011, 37, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deater-Deckard, K.; Chary, M.; McQuillan, M.E.; Staples, A.D.; Bates, J.E. Mothers’ sleep deficits and cognitive performance: Moderation by stress and age. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0241188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krizan, Z.; Hisler, G. Sleepy anger: Restricted sleep amplifies angry feelings. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2019, 148, 1239–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.J.; Cho, M.J.; Kim, M.J. Mothers’ parenting stress and neighborhood characteristics in early childhood (ages 0–4). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura Paroche, M.; Caton, S.J.; Vereijken, C.M.J.L.; Weenen, H.; Houston-Price, C. How infants and young children learn about food: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaglioni, S.; De Cosmi, V.; Ciappolino, V.; Parazzini, F.; Brambilla, P.; Agostoni, C. Factors influencing children’s eating behaviours. Nutrients 2018, 10, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.L.; Goodell, L.S.; Williams, K.; Power, T.G.; Hughes, S.O. Getting my child to eat the right amount. Mothers’ considerations when deciding how much food to offer their child at a meal. Appetite 2015, 88, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, A.L.; Low, C.A. Expressing emotions in stressful contexts: Benefits, moderators, and mechanisms. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 21, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani Amir, H.; Ahmadi Gatab, T.; Shayan, N. Relationship between Type A Personality and Mental Health. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 30, 2010–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Plickert, G.; Pals, H. Parental anger and trajectories of emotional well-being from adolescence to young adulthood. J. Res. Adolesc. 2020, 30, 440–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holloway, S.D.; Suzuki, S.; Yamamoto, Y.; Mindnich, J.D. Relation of maternal role concepts to parenting, employment choices, and life satisfaction among Japanese women. Sex Roles 2006, 54, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elson, D. Labor markets as gendered institutions: Equality, efficiency and empowerment issues. World Dev. 1999, 27, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajgariah, R.; Malenahalli Chandrashekarappa, S.; Venkatesh Babu, D.K.; Gopi, A.; Murthy Mysore Ramaiha, N.; Kumar, J. Parenting stress and coping strategies adopted among working and non-working mothers and its association with socio-demographic variables: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2021, 9, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | N | Descriptive Statistics |

|---|---|---|

| Mother’s age in years, median [25th centile, 75th centile] | 100 | 33.000 [30.000–36.500] |

| First child’s age in years, median [25th centile, 75th centile] | 103 | 2.000 [1.000–3.000] |

| q2 (How often do you use the square?) | 103 | |

| Came for the first time | 2 (1.94%) | |

| Less than once a month | 24 (23.30%) | |

| Twice a month | 16 (15.53%) | |

| Three times a month | 11 (10.68%) | |

| Once a week | 23 (22.33%) | |

| Two-three times a week | 24 (23.30%) | |

| Four or more times a week | 3 (2.91%) | |

| Q2 (converted “How often do you use the square?”) | 103 | |

| Less than four times a month | 53 (51.46%) | |

| At least four times a month | 50 (48.54%) | |

| q3 (Distance of people you can rely on for childcare) | 103 | |

| Living together | 5 (4.85%) | |

| Within walking distance | 3 (2.91%) | |

| Within 5 min by car | 17 (16.50%) | |

| Within 30 min by car | 23 (22.33%) | |

| Within 1 h by car | 18 (17.48%) | |

| Within 2 h by car | 26 (25.24%) | |

| More than 3 h by car | 8 (7.77%) | |

| None | 3 (2.91%) | |

| q5 (Sleep duration), median [25th centile, 75th centile] | 102 | 6.000 [6.000–7.000] |

| q6 (Wake up times) | 103 | |

| Irregular times | 6 (5.83%) | |

| Sometimes irregular times | 19 (18.45%) | |

| Approximately the same time daily | 63 (61.17%) | |

| Always the same time | 15 (14.56%) | |

| q7 (Do you have concerns regarding childcare?) | 103 | |

| No | 33 (32.04%) | |

| Yes | 70 (67.96%) | |

| q8 (Do you work?) | 103 | |

| Not working | 80 (77.67%) | |

| On childcare leave | 14 (13.59%) | |

| Working | 9 (8.74%) | |

| Tiredness score, median [25th centile, 75th centile] | ||

| Drowsiness | 103 | 13.000 [9.000–17.000] |

| Instability | 103 | 9.000 [7.000–14.000] |

| Uneasiness | 103 | 8.000 [6.000–12.000] |

| Local pain dullness | 103 | 11.000 [8.000–15.000] |

| Eyestrain | 103 | 7.000 [5.000–12.000] |

| q9 Anger Situations | ||

| q9.1 (When a child does not get up easily in the morning) | 102 | |

| I don’t get angry | 94 (92.16%) | |

| I get angry sometimes | 6 (5.88%) | |

| I get angry | 2 (1.96%) | |

| q9.2 (When a child has hard time sleeping at night) | 102 | |

| I don’t get angry | 53 (51.96%) | |

| I get angry sometimes | 29 (28.43%) | |

| I get angry | 20 (19.61%) | |

| q9.3 (When a child wakes up in the middle of the night) | 102 | |

| I don’t get angry | 92 (90.20%) | |

| I get angry sometimes | 7 (6.86%) | |

| I get angry | 3 (2.94%) | |

| q9.4 (When a child takes a long time to eat a meal) | 102 | |

| I don’t get angry | 36 (35.29%) | |

| I get angry sometimes | 29 (28.43%) | |

| I get angry | 37 (36.27%) | |

| q9.5 (When a child eats only what he/she likes and leaves behind what he/she dislikes) | 102 | |

| I don’t get angry | 52 (50.98%) | |

| I get angry sometimes | 30 (29.41%) | |

| I get angry | 20 (19.61%) | |

| q9.6 (When a child does not change clothes easily) | 102 | |

| I don’t get angry | 53 (51.96%) | |

| I get angry sometimes | 27 (26.47%) | |

| I get angry | 22 (21.57%) | |

| q9.7 (When a child has hard time taking a bath) | 102 | |

| I don’t get angry | 67 (65.69%) | |

| I get angry sometimes | 21 (20.59%) | |

| I get angry | 14 (13.73%) | |

| q9.8 (When a child clutters the house) | 101 | |

| I don’t get angry | 52 (51.49%) | |

| I get angry sometimes | 35 (34.65%) | |

| I get angry | 14 (13.86%) | |

| q9.9 (When a child does not go home easily even when it is time to go home from the park or elsewhere) | 101 | |

| I don’t get angry | 58 (57.43%) | |

| I get angry sometimes | 33 (32.67%) | |

| I get angry | 10 (9.90%) | |

| q9.10 (When a child does not stop crying) | 103 | |

| I don’t get angry | 72 (69.90%) | |

| I get angry sometimes | 26 (25.24%) | |

| I get angry | 5 (4.85%) | |

| Sense of time urgency, median [25th centile, 75th centile] | 103 | 12.000 [8.000–16.500] |

| Variables | Kruskal–Wallis Chi-Squared | Wilcoxon V | df | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother’s age | 0 | 3.841 × 10−18 | ||

| Child’s age | 5090 | 1.594 × 10−17 | ||

| Frequency of using the square | 8.699 | 6 | 0.191 | |

| Conversion frequency of using the square | 3.909 | 1 | 0.048 | |

| People you can rely on for childcare | 7.362 | 7 | 0.392 | |

| q5 (Sleep duration) | 4541 | 5.464 × 10−13 | ||

| q6 (Wake up time) | 1.167 | 3 | 0.761 | |

| q7 (Do you have concerns regarding childcare?) | 4.306 | 1 | 0.038 | |

| q8 (Do you work?) | 1.625 | 2 | 0.444 | |

| Tired score | ||||

| Drowsiness | 2325.5 | 0.493 | ||

| Instability | 3308 | 0.00079 | ||

| Uneasiness | 3723 | 4.209 × 10−6 | ||

| Local pain or dullness | 3020.5 | 0.088 | ||

| Eyestrain | 3685.5 | 2.436 × 10−6 | ||

| q9 Anger by Situation | ||||

| q9.1 (When a child does not get up easily in the morning) | 2.197 | 2 | 0.333 | |

| q9.2 (When a child has hard time sleeping at night) | 6.254 | 2 | 0.044 | |

| q9.3 (When a child wakes up in the middle of the night) | 8.981 | 2 | 0.011 | |

| q9.4 (When it takes long time for a child to eat a meal) | 7.652 | 2 | 0.022 | |

| q9.5 (When a child eats only what they like and leaves behind what they dislike) | 1.059 | 2 | 0.589 | |

| q 9.6 (When a child does not change their clothes easily) | 5.404 | 2 | 0.067 | |

| q9.7 (When a child has hard time taking a bath) | 5.781 | 2 | 0.056 | |

| q9.8 (When a child clutters the house) | 2.281 | 2 | 0.320 | |

| q9.9 (When a child does not go home easily even when it is time to go home from the park or elsewhere) | 3.089 | 2 | 0.213 | |

| q9.10 (When a child does not stop crying) | 4.573 | 2 | 0.102 |

| Variables | Estimate | Std. Error | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 19.09 | 5.97 | 3.20 | 0.002 |

| Mother’s age | −0.01 | 0.14 | −0.10 | 0.924 |

| Child’s age | 0.29 | 0.23 | 1.22 | 0.227 |

| q5 (Sleep duration in hours) | −1.61 | 0.58 | −2.76 | 0.007 |

| Do you work? | (Ref. not working) | |||

| q8 (On childcare leave) | 1.71 | 1.73 | 0.99 | 0.325 |

| q8 (Working) | 3.37 | 2.29 | 1.47 | 0.146 |

| Tired score vlue | ||||

| Instability | 0.41 | 0.15 | 2.74 | 0.008 |

| Local pain or dullness | −0.24 | 0.17 | −1.38 | 0.172 |

| q9 Anger by Situation | ||||

| When a child wakes up in the middle of the night | (Ref. not angry) | |||

| q9.3 (I get angry sometimes) | 5.24 | 2.23 | 2.35 | 0.021 |

| q9.3 (I get angry) | 8.05 | 3.22 | 2.50 | 0.015 |

| When it takes long time for a child to eat a meal | (Ref. not angry) | |||

| q9.4 (I get angry sometimes) | −0.98 | 1.67 | −0.59 | 0.560 |

| q9.4 (I get angry) | 2.87 | 1.50 | 1.91 | 0.060 |

| When a child eats only what they like and leaves behind what they dislike | (Ref. not angry) | |||

| q9.5 (I get angry sometimes) | −3.04 | 1.65 | −1.84 | 0.070 |

| q9.5 (I get angry) | −1.63 | 1.66 | −0.98 | 0.331 |

| When a child has hard time taking a bath | (Ref. not angry) | |||

| q9.7 (I get angry sometimes) | 2.01 | 1.64 | 1.23 | 0.224 |

| q9.7 (I get angry) | 0.75 | 1.94 | 0.39 | 0.698 |

| When a child clutters the house | (Ref. not angry) | |||

| q9.8 (I get angry sometimes) | 1.59 | 1.51 | 1.05 | 0.296 |

| q9.8 (I get angry) | −3.38 | 1.98 | −1.71 | 0.092 |

| When a child does not go home easily even when it is time to go home from the park or elsewhere | (Ref. not angry) | |||

| q9.9 (I get angry sometimes) | 1.39 | 1.56 | 0.89 | 0.378 |

| q9.9 (I get angry) | 0.08 | 2.22 | 0.04 | 0.972 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kawasaki, H.; Yamasaki, S.; Nishiyama, M.; D’Angelo, P.; Cui, Z. Relationship between the Type A Personality Concept of Time Urgency and Mothers’ Parenting Situation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16327. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416327

Kawasaki H, Yamasaki S, Nishiyama M, D’Angelo P, Cui Z. Relationship between the Type A Personality Concept of Time Urgency and Mothers’ Parenting Situation. Sustainability. 2022; 14(24):16327. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416327

Chicago/Turabian StyleKawasaki, Hiromi, Satoko Yamasaki, Mika Nishiyama, Pete D’Angelo, and Zhengai Cui. 2022. "Relationship between the Type A Personality Concept of Time Urgency and Mothers’ Parenting Situation" Sustainability 14, no. 24: 16327. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416327

APA StyleKawasaki, H., Yamasaki, S., Nishiyama, M., D’Angelo, P., & Cui, Z. (2022). Relationship between the Type A Personality Concept of Time Urgency and Mothers’ Parenting Situation. Sustainability, 14(24), 16327. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416327