The Empowerment of Saudi Arabian Women through a Multidimensional Approach: The Mediating Roles of Self-Efficacy and Family Support

Abstract

:1. Introduction and Background

What are the factors that create empowerment among women in Saudi Arabia?

How do SFY and FS help develop the association of EE, SE and PE empowerment with WE?

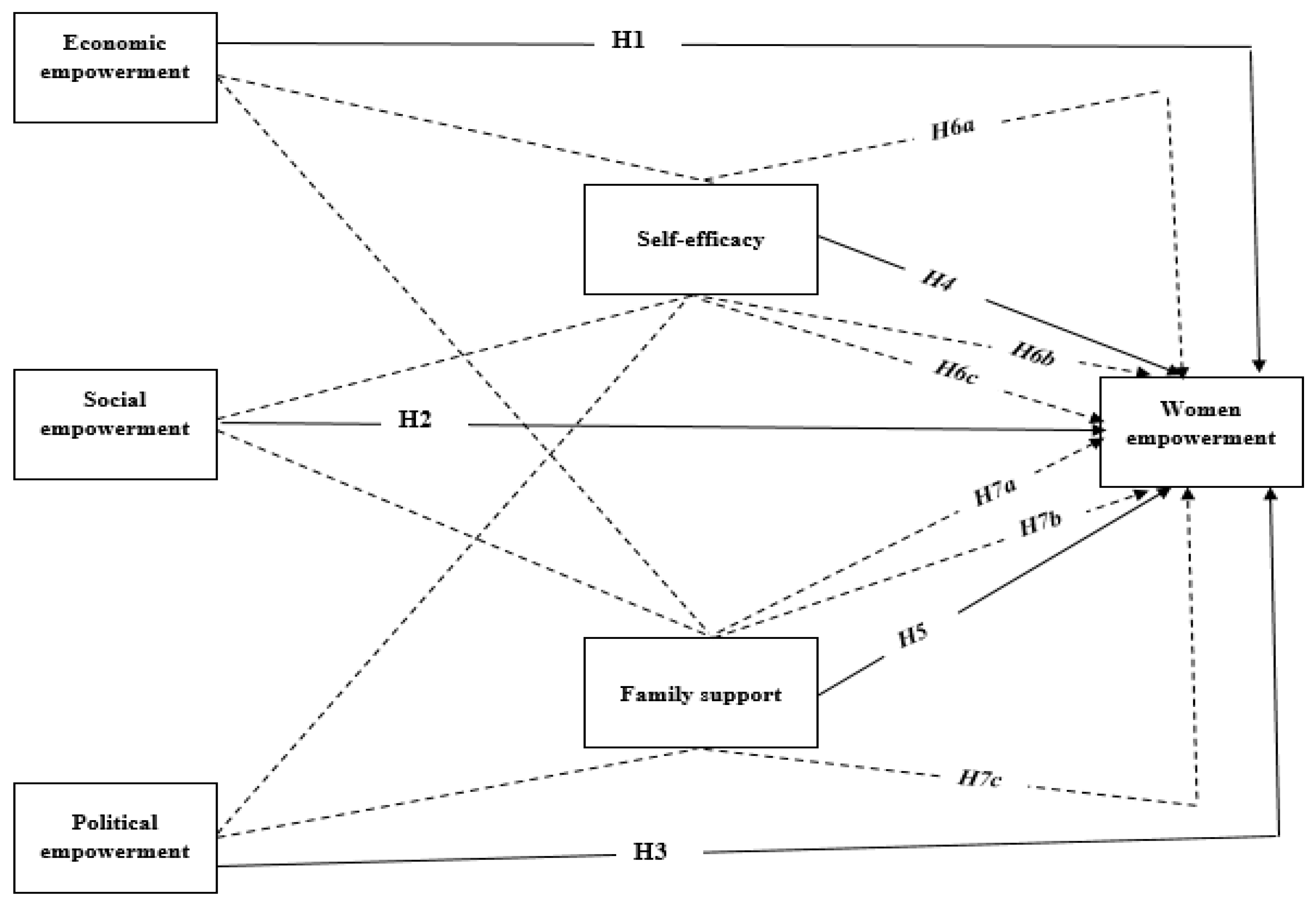

2. Literature Review and Development of the Hypotheses

2.1. Empowerment Dimensions and Women Empowerment (WE)

2.2. Self-Efficacy (SFY) and Women Empowerment (WE)

2.3. Family Support (FS) and Women Empowerment (WE)

2.4. The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy (SFY)

2.5. The Mediating Role of Family Support (FS)

3. Research Methods

3.1. Approach

3.2. Respondents and Data Collection

3.3. Scale Validation

3.4. Measures

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Demography

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

4.3. Measurement Model

4.4. Structural Model

4.4.1. Model Fitness

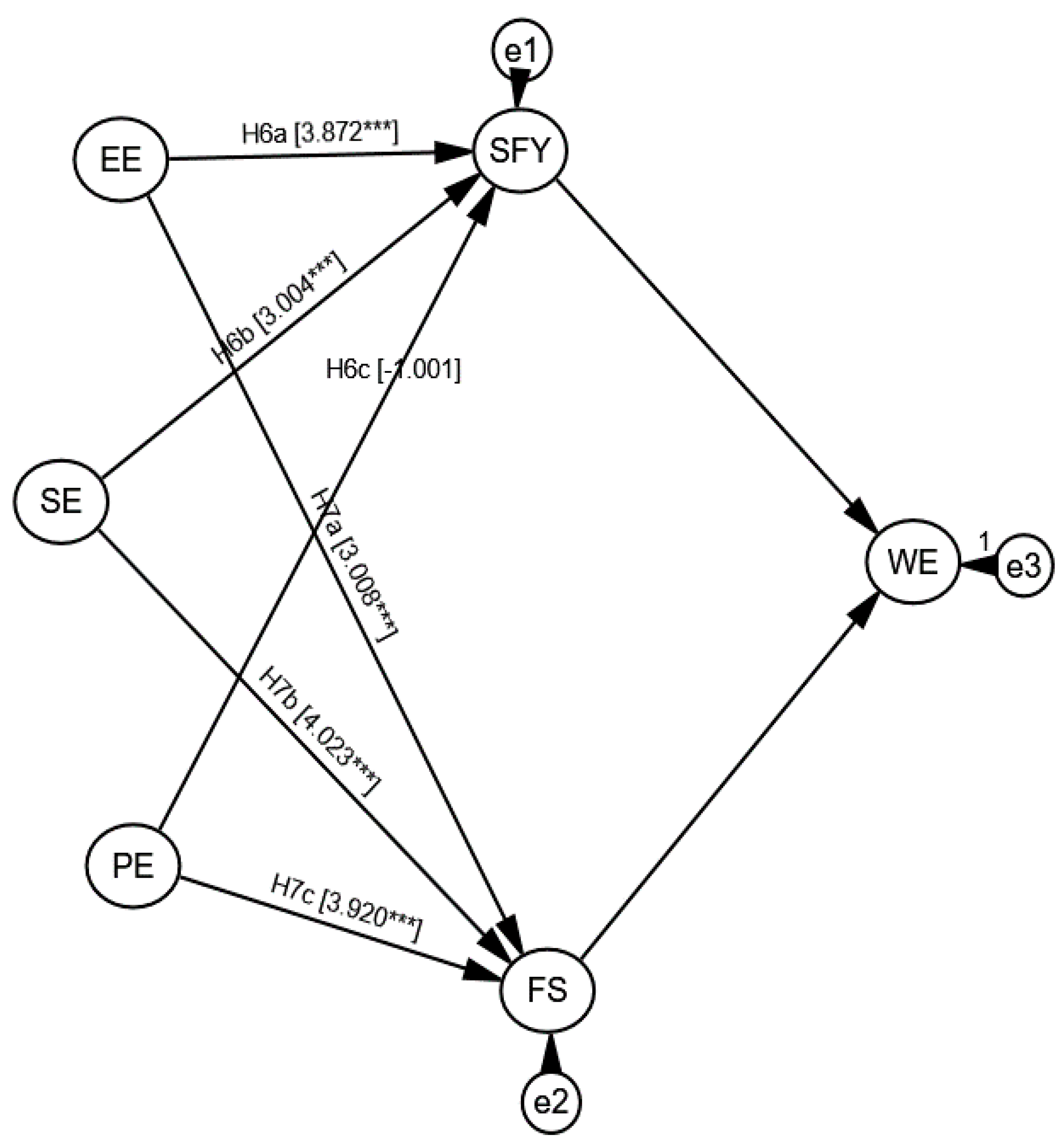

4.4.2. Assessment of Hypotheses

5. Discussion and Conclusions

6. Limitations, Implications and Future Research Paths

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Factor | Item Description | Source |

| Economic empowerment [EE] | 1. I believe that monthly expenditure on food increased after joining enterprise. | [13,99] |

| 2. I believe that monthly savings increased after joining enterprise. | ||

| 3. I believe that credit facilities increased after joining enterprise. | ||

| 4. I believe that enterprise is beneficial for employment generation. | ||

| Social empowerment [SE] | 1. I believe that family relations improved after joining enterprise. | [13,99] |

| 2. I believe that marital relations improved after joining enterprise. | ||

| 3. I believe that self-confidence improved after joining enterprise. | ||

| 4. I believe that I am a person of worth, at least on an equal basis with others. | ||

| 5. Overall, I am satisfied with myself. | ||

| Political empowerment [PE] | 1. I believe that political awareness is necessary for enterprise members. | [13,99] |

| 2. I believe that political involvement is necessary for enterprise members. | ||

| 3. I believe that contact with the political leaders improves your group position. | ||

| Self-efficacy [SFY] | 1. I can solve the problems that happen to my life. | [36] |

| 2. I have control over things that happen in my life. | ||

| 3. If I set my mind on some goals, I can do it effectively. | ||

| 4. My actions can result in what will happen to me in the future. | ||

| 5. I can change and fix important things to make it better for the future. | ||

| Family support [FS] | 1. My family members will approve my actions. | [100] |

| 2. My family members encourage me to work in enterprise. | ||

| 3. If necessary, my family members loan me money to help me to work in enterprise. | ||

| 4. If necessary, my family members provide me with materials and equipment to help me while working in enterprise. | ||

| 5. My family members give me advice to work in enterprise or start my own business. | ||

| Women empowerment [WE] | 1. It is meaningful for me to do my work. | [13,36,99] |

| 2. I am competent to do my work. | ||

| 3. I am autonomous doing my work. | ||

| 4. My impact is strong when I bring myself into my work. |

References

- Ghasemi, M.; Badsar, M.; Falahati, L.; Karamidehkordi, E. Investigating the mediating role of self-esteem and self-efficacy in analysis of the socio-cultural factors influencing rural women’s empowerment. Women’s Stud. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 17, 151–186. [Google Scholar]

- Tawfik, T.; Alkhateeb, Y.; Abdalla, M.; Abdalla, Z.; Abdo, S.; Elsayed, M.; Mawad, E. The economic empowerment of Saudi Women in the light of Saudi Vision 2030. Asian Econ. Financ. Rev. 2020, 10, 1269–1279. [Google Scholar]

- Varshney, D. The strides of the Saudi female workforce: Overcoming constraints and contradictions in transition. J. Int. Women’s Stud. 2019, 20, 359–372. [Google Scholar]

- Naseem, S.; Dhruva, K. Issues and challenges of Saudi female labor force and the role of Vision 2030. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2017, 7, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sohail, M. Women empowerment and economic development-an exploratory study in Pakistan. J. Bus. Stud. Q. 2014, 5, 210–221. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrajunnisa, M.; Jabeen, F. Ranking the enablers promoting female empowerment in the UAE health care sector. Int. J. Gend. Entrepr. 2020, 12, 117–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyanto, E.K.; Perdhana, M.S.; Rahmawati, S.N.; Ariefiantoro, T. Psychological empowerment and women entrepreneurial success: The mediating role of proactive behavior. Acad. Entrepr. J. 2021, 27, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rudhumbu, N.; du Plessis, E.; Maphosa, C. Challenges and opportunities for women entrepreneurs in Botswana: Revisiting the role of entrepreneurship education. J. Int. Educ. Bus. 2020, 13, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Kumar, P.; Garg, V. Empowering SHGs Women through Micro-finance in Uttar Pradesh. Int. J. Law Manag. 2020, 62, 591–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurasyiah, A.; Miyasto, M.; Mariyanti, T.; Beik, I.S. Women’s empowerment and family poverty in the Tawhidi epistemological approach. Int. J. Ethic Syst. 2020, 37, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazier, H.; Ramadan, R. What empowers Egyptian women: Resources versus social constrains? Rev. Econ. Polit. Sci. 2019, 3, 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golzard, V. Economic empowerment of Iranian women through the internet. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2019, 35, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Gupta, S.D.; Upadhyay, P. Empowering women and stimulating development at bottom of pyramid through micro-entrepreneurship. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, E. Women and politics: A case study of political empowerment of Indian women. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2020, 40, 607–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranabahu, N.; Tanima, F.A. Empowering vulnerable microfinance women through entrepreneurship: Opportunities, challenges and the way forward. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2021, 14, 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, S.; Burke, G.M.; Cannonier, C. African American women leadership across contexts: Examining the internal traits and external factors on women leaders’ perceptions of empowerment. J. Manag. Hist. 2020, 26, 353–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, N. Role of cooperatives in economic empowerment of women: A review of Indian experiences. World J. Entrepr. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 17, 617–631. [Google Scholar]

- Duque, P.J.A.; Moreno, C.S.E. Informal entrepreneurship and women’s empowerment—The case of street vendors in urban Colombia. Int. J. Gend. Entrepr. 2022, 14, 188–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S. Role of Islamic microfinance in women’s empowerment: Evidence from rural development scheme of Islami Bank Bangladesh limited. ISRA Int. J. Islam. Financ. 2021, 13, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaya, N.; Khait, A.R. Feminizing leadership in the Middle East: Emirati women empowerment and leadership style. Gend. Manag. 2017, 32, 590–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.; Svels, K. Women’s empowerment in small-scale fisheries: The impact of Fisheries Local Action Groups. Mar. Policy 2022, 136, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Siano, R.; Chiariello, V. Women’s political empowerment and welfare policy decisions: A spatial analysis of European countries. Spat. Econ. Anal. 2021, 17, 101–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, B.A.; Mangi, S.; Barkat, N.; Mirjat, A.J. Socio-cultural and economic obstacles faced by female students of Baluchistan, Pakistan: An academic achievement perspective. Int. J. Res. Sci. Innov. 2019, 6, 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kluczewska, K. Donor-Funded Women’s Empowerment in Tajikistan: Trajectories of Women’s NGOs and Changing Attitudes to the International Agenda. Stud. Comp. Int. Dev. 2021, 57, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awoa, P.A.; Ondoa, H.A.; Tabi, H.N. Women’s political empowerment and natural resource curse in developing countries. Resour. Policy 2022, 75, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi, S.; Hall, C.M.; Vo-Thanh, T. The gendered effects of statecraft on women in tourism: Economic sanctions, women’s disempowerment and sustainability? J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 30, 1736–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucy, D.M.; Ghosh, J.; Kujawa, E. Empowering women’s leadership: A case study of Bangladeshi microcredit business. SAM Adv. Manag. J. 2008, 73, 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Belwal, R.; Belwal, S. Employers’ perception of women workers in Oman and the challenges they face. Empl. Relat. 2017, 39, 1048–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.K. Indian women in grassroots socio-political institutions: Impact of microfinance through self-help groups. Int. J. Indian Cult. Bus. Manag. 2018, 17, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.U.; Goldsmith, A.H.; Rajaguru, G. Women’s empowerment over recreation and travel expenditures in Pakistan: Prevalence and determinants. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2021, 2, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-H.; Chang, C.-C.; Yao, S.-N.; Liang, C. The contribution of self-efficacy to the relationship between personality traits and entrepreneurial intention. High. Educ. 2015, 72, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, S.A.; Ahmed, H.K.; Qureshi, S.N. Economic and psycho-social determinants of psychological empowerment in women. Pak. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 14, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu, K.Y.; Ahmed, Q. Role of family support technical training in women empowerment. Latest Trends Text. Fash. Des. 2018, 3, 280–285. [Google Scholar]

- Sabri, N.A.A.; Zainol, N.R.; Daud, N.I.M.; Uthamaputhran, S.; Aziz, M.I. Self-efficacy on social capital and financial empowerment towards socioeconomic wellbeing development among women participants in Malaysia. In International Conference on Business and Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 466–477. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qahtani, A.M.; A Ibrahim, H.; Elgzar, W.T.; A El Sayed, H.; Essa, R.M.; A Abdelghaffar, T. The role of self-esteem and self-efficacy in women empowerment in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2021, 25, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Yoopetch, C. Women empowerment, attitude toward risk-taking and entrepreneurial intention in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2020, 15, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramanandam, A.D.; Packirisamy, P. An empirical study on the impact of micro enterprises on women empowerment. J. Enterp. Commun. People Places Global Econ. 2015, 9, 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, S.A.; Batool, S.S. Impact of education on women’s empowerment: Mediational role of income and self-esteem. J. Res. Reflect. Educ. 2018, 12, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Nasima, A.; Shalini, P. Personal factors, mediating role of self-efficacy of women entrepreneurs on entrepreneurial performance. Eurasian J. Anal. Chem. 2019, 13, 205. [Google Scholar]

- Sulistyani, N.W.; Suhariadi, F. Fajrianthi Self-Efficacy as a Mediator of the Impact of Social Capital on Entrepreneurial Orientation: A Case of Dayak Ethnic Entrepreneurship. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qahir, A.; Karim, J.; Kakar, A.S. The mediating role of self-efficacy between emotional intelligence and employees’ creativity. Pak. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2022, 6, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, R.B.; Wallentin, F.Y. Factors empowering women in Indian self-help group programs. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 2012, 26, 425–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Khanam, R.; Nghiem, S. The effects of microfinance on women’s empowerment: New evidence from Bangladesh. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2017, 44, 1745–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afiouni, F.; Karam, C.M.; Makarem, Y. Contextual embeddedness of careers: Female “nonsurvivors” and their gendered relational context. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2019, 30, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayeh, E. The role of empowering women and achieving gender equality to the sustainable development of Ethiopia. Pac. Sci. Rev. B: Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2016, 2, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballon, P. A Structural Equation Model of Female Empowerment. J. Dev. Stud. 2017, 54, 1303–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, M.; Chiappori, P.A. Efficient Intra-Household Allocations: A General Characterization and Empirical Tests. Econometrica 1998, 66, 1241–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bardhan, K.; Klasen, S. UNDP’s gender-related indices: A critical review. World Dev. 1999, 27, 985–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beteta, H.C. What is missing in measures of women’s empowerment? J. Hum. Dev Capab. 2006, 7, 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.M.; Schuler, S.R.; Riley, A.P. Rural credit programs and women’s empowerment in Bangladesh. World Dev. 1996, 24, 635–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, M.M.; Khandker, S.R.; Cartwright, J. Empowering Women with Micro Finance: Evidence from Bangladesh. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 2006, 54, 791–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nadim, S.J.; Nurlukman, A.D. The impact of women empowerment on poverty reduction in rural area of Bangladesh: Focusing on village development program. J. Gov. Civil Soc. 2017, 1, 135–157. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, M.A. Psychological empowerment: Issues and illustrations. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1995, 23, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Johnson, D.M.; Worell, J.; Chandler, R.K. Assessing Psychological Health and Empowerment in Women: The Personal Progress Scale Revised. Women Health 2005, 41, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.G.; Maschi, T.M. Feminist and empowerment theory and social work practice. J. Soc. Work. Prac. 2014, 29, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, F.; Kickul, J.; Marlino, D. Gender, Entrepreneurial Self–Efficacy, and Entrepreneurial Career Intentions: Implications for Entrepreneurship Education. Entrep. Theory Prac. 2007, 31, 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Lian, K.; Hong, P.; Liu, S.; Lin, R.-M.; Lian, R. Teachers’ Emotional Intelligence and Self-efficacy: Mediating Role Of Teaching Performance. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2019, 47, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardana, L.W.; Narmaditya, B.S.; Wibowo, A.; Mahendra, A.M.; Wibowo, N.A.; Harwida, G.; Rohman, A.N. The impact of entrepreneurship education and students’ entrepreneurial mindset: The mediating role of attitude and self-efficacy. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbu, Y.B.; Sato, S. Credit card literacy and financial well-being of college students: A moderated mediation model of self-efficacy and credit card number. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 37, 991–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Ali, I.; Badghish, S.; Soomro, Y.A. Determinants of Financial Empowerment Among Women in Saudi Arabia. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banach, M.; Iudice, J.; Conway, L.; Couse, L.J. Family Support and Empowerment: Post Autism Diagnosis Support Group for Parents. Soc. Work. Groups 2010, 33, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoardi, C.; Galletta, M.; Battistelli, A.; Cangialosi, N. Effects of beliefs, motivation and entrepreneurial self-efficacy on entrepreneurial intentions: The moderating role of family support. Rocz. Psychol. 2018, 21, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Le, Q.H.; Loan, N.T. Role of entrepreneurial competence, entrepreneurial education, family support and entrepreneurship policy in forming entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial decision. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2022, 16, 204–221. [Google Scholar]

- Rathiranee, Y.; Semasinghe, D.M. Factors determining the women empowerment through microfinance: An empirical study in Sri Lanka. Int. J. Soc. Behav. Edu. Econ. Bus. Indust. Eng. 2015, 9, 1595–1599. [Google Scholar]

- Saqib, N.; Aggarwal, P.; Rashid, S. Women empowerment and economic growth: Empirical evidence from Saudi Arabia. Adv. Manag. Appl. Econ. 2016, 6, 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Luszczynska, A.; Durawa, A.B.; Scholz, U.; Knoll, N. Empowerment beliefs and intention to uptake cervical cancer screening: Three psychosocial mediating mechanisms. Women Health 2012, 52, 162–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taştan, S.B. The relationship between psychological empowerment and psychological wellbeing: The role of self-efficacy perception and social support. Öneri Derg. 2013, 10, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thompson, M.P.; Kaslow, N.J.; Short, L.M.; Wyckoff, S. The mediating roles of perceived social support and resources in the self-efficacy-suicide attempts relation among African American abused women. J. Consul. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 70, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. The Relationship Between Employee Psychological Empowerment and Proactive Behavior: Self-efficacy As Mediator. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2017, 45, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, V.; Bharadwaja, M.; Yadav, S.; Kabra, G. Team-member exchange and innovative work behaviour: The role of psychological empowerment and creative self-efficacy. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2018, 11, 344–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, G.T.T. The effect of transformational leadership on nonfamily international intrapreneurship behavior in family firms: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. J. Asian Bus. Econ. Stud. 2021, 28, 204–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizar, Y. Work Flexibility and Job Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Employee Empowerment. Ph.D. Thesis, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakhan, S.A.; Sohu, J.M.; Mustafa, S.; Sohu, S.A. Factors influencing political orientation: Mediating role of women empowerment. Int. J. Manag. 2021, 12, 786–795. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrawijaya, A.T. Demographic Factors and Employee Performance: The Mediating Effect of Employee Empowerment. Media Èkon. Manaj. 2019, 34, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, A.; Dhaliwal, R.S.; Nobi, K. Impact of Structural Empowerment on Organizational Commitment: The Mediating Role of Women’s Psychological Empowerment. Vision: J. Bus. Perspect. 2018, 22, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldabbas, H.; Pinnington, A.; Lahrech, A. The mediating role of psychological empowerment in the relationship between knowledge sharing and innovative work behaviour. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2020, 25, 2150014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso Castro, C.; Villegas Periñán, M.M.; Casillas Bueno, J.C. Transformational leadership and followers’ attitudes: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 1842–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Lee, G.; Murrmann, S.K.; George, T.R. Motivational effects of empowerment on employees’ organizational commitment: A mediating role of management trustworthiness. Cornel. Hosp. Q. 2012, 53, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmjooei, P.; Zarei, R. The mediating role of psychological empowerment in the relationship of perceived organizational support and perceived social support with the work quality of life. Psychol. Methods Models 2018, 9, 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ganji, G.S.F.; Johnson, L.W.; Babazadeh Sorkhan, V.; Banejad, B. The effect of employee empowerment, organizational support, and ethical climate on turnover intention: The mediating role of job satisfaction. Iran. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 14, 311–329. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, N.; Bharadwaja, M. Empowering Leadership and Psychological Health: The Mediating Role of Psychological Empowerment. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2020, 32, 97–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, K.N.; Shelton, T.L. Family Empowerment as a Mediator between Family-Centered Systems of Care and Changes in Child Functioning: Identifying an Important Mechanism of Change. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2007, 16, 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savela, T. The advantages and disadvantages of quantitative methods in schoolscape research. Linguistics Educ. 2018, 44, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramona, S.E. Advantages and disadvantages of quantitative and qualitative information risk approaches. Chin. Bus. Rev. 2011, 10, 1106–1110. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, R.A.; Gullone, E. Why we should not use 5-point Likert scales: The case for subjective quality of life measurement. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Quality Of Life in Cities, Singapore, 8–10 March 2000; Volume 74, pp. 74–93. [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Arabia Population Statistics GMI. 2022. Available online: https://www.globalmediainsight.com/blog/saudi-arabia-population-statistics/#:~:text=Gender%20Split&text=In%20Saudi%20Arabia%2C%20the%20male%20population%20is%2020.70%20million%20i.e.,i.e.,%2042.24%25%20of%20the%20population (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Trading Economics Saudi Arabia—Population, Female (% of Total). 2022. Available online: https://tradingeconomics.com/saudi-arabia/population-female-percent-of-total-wb-data.html (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Dommeyer, C.J.; Baum, P.; Chapman, K.S.; Hanna, R.W. Attitudes of Business Faculty Towards Two Methods of Collecting Teaching Evaluations: Paper vs. Online. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2002, 27, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.T.E. Instruments for obtaining student feedback: A review of the literature. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2005, 30, 387–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nulty, D.D. The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: What can be done? Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2008, 33, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ballantyne, C. Measuring Quality Units: Considerations in Choosing Mandatory Questions. In Proceedings of the Evaluations and Assessment Conference: A Commitment to Quality, Adelaide, Australia, 24–25 November 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Altamimi, D.; Ab Rashid, R. Spelling Problems and Causes among Saudi English Language Undergraduates. Arab World Engl. J. 2019, 10, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ur Rahman, M.M.; Alhaisoni, E. Teaching English in Saudi Arabia: Prospects and challenges. Acad. Res. Int. 2013, 4, 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Faruk, S. English language teaching in Saudi Arabia: A world system perspective. Sci. Bull. Politeh. Univ. Timiş. Trans. Mod. Lang. 2013, 12, 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Alshahrani, M. A brief historical perspective of English in Saudi Arabia. J. Lit. Lang. Linguist. 2016, 26, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, K.H. Writing for the Journal of Nursing Education: Key Questions for Authors. J. Nurs. Educ. 2014, 53, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gray, J.; Brain, K.; Iredale, R.; Alderman, J.; France, E.; Hughes, H. A pilot study of telegenetics. J. Telemed. Telecare 2000, 6, 245–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, R.B.; Floro, M. Reducing vulnerability through microfinance: Evidence from Indian self-help group program. J. Dev. Stud. 2012, 48, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, A.E.; Settles, A.; Shen, T. Does family support matter? The influence of support factors on entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions of college students. Acad. Entrepr. J. 2017, 23, 24–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, E.; Halle, T.; Terry-Humen, E.; Lavelle, B.; Calkins, J. Children’s school readiness in the ECLS-K: Predictions to academic, health, and social outcomes in first grade. Early Child. Res. Q. 2006, 21, 431–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, S.J.; Rosenberg, N. An overview of innovation. In Studies on Science and the Innovation Process: Selected Works of Nathan Rosenberg; World Scientific: Singapore, 2010; pp. 173–203. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Muller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and goodness-of-fit models. Methods Psychol. Res. Online 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton, B.; Muthen, B.; Alwin, D.F.; Summers, G. Assessing reliability and stability in panel models. Soc. Methodol. 1977, 8, 84–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Alhareth, Y.; Al Alhareth, Y.; Al Dighrir, I. Review of women and society in Saudi Arabia. Am. J. Educ. Res. 2015, 3, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karolak, M.; Guta, H. Saudi Women as Decision Makers: Analyzing the Media Portrayal of Female Political Participation in Saudi Arabia. HAWWA 2020, 18, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaleh, S.A. Gender inequality in Saudi Arabia: Myth and reality. Int. Proc. Econ. Dev. Res. 2012, 39, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Le Renard, A. “Only for Women:” Women, the State, and Reform in Saudi Arabia. Middle East J. 2008, 62, 610–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilotti, M.A.; Abdulhadi, E.J.; Algouhi, T.A.; Salameh, M.H. The new and the old: Responses to change in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Int. Women’s Stud. 2021, 22, 341–358. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marital status | Single | 92 | 29.3 |

| Marital Status | 163 | 51.9 | |

| Divorced | 25 | 8.0 | |

| Widow/Widower | 34 | 10.8 | |

| Total | 314 | 100.0 | |

| Education level | Primary | 15 | 4.8 |

| Secondary | 31 | 9.9 | |

| Intermediate | 20 | 6.4 | |

| Diploma | 24 | 7.6 | |

| Higher diploma | 23 | 7.3 | |

| Bachelor degree | 166 | 52.9 | |

| Master’s degree | 34 | 10.8 | |

| Ph.D. | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Total | 314 | 100.0 | |

| Province | Eastern | 106 | 33.8 |

| Western | 131 | 41.7 | |

| Central | 60 | 19.1 | |

| Northern | 12 | 3.8 | |

| Southern | 5 | 1.6 | |

| Total | 314 | 100.0 | |

| Family dynamics | Nuclear family | 210 | 66.88 |

| Extended family | 104 | 33.12 | |

| Total | 314 | 100.0 | |

| Gender role | Patriarchy | 228 | 72.61 |

| Matriarchy | 86 | 27.39 | |

| Total | 314 | 100.0 | |

| Supportive networks | Family | 240 | 76.43 |

| Friends | 52 | 16.56 | |

| Relatives | 22 | 7.01 | |

| Total | 314 | 100.0 | |

| Household/family headed by | Male | 266 | 84.71 |

| Female | 48 | 15.29 | |

| Total | 314 | 100.0 |

| Variables | Mean | Std. Deviation | WE | EE | SE | PE | SFY | FS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WE | 3.219 | 0.315 | - | |||||

| EE | 3.823 | 1.150 | 0.341 ** | - | ||||

| SE | 3.536 | 1.182 | −0.123 | 0.293 ** | - | |||

| PE | 2.003 | 1.992 | 0.400 ** | 0.421 ** | 0.139 * | - | ||

| SFY | 2.982 | 1.280 | 0.329 ** | 0.381 ** | 0.366 ** | 0.109 * | - | |

| FS | 3.221 | 1.232 | 0.451 ** | 0.421 ** | 0.442 ** | 0.351 ** | 0.387 ** | - |

| Construct | Item Code | Factor Loadings | CR | AVE | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic empowerment [EE] | ee1 | 0.882 | 0.877 | 0.838 | 0.862 |

| ee3 | 0.872 | ||||

| ee2 | 0.852 | ||||

| ee4 | 0.833 | ||||

| Social empowerment [SE] | se1 | 0.842 | 0.828 | 0.802 | 0.827 |

| se5 | 0.825 | ||||

| se2 | 0.810 | ||||

| se3 | 0.809 | ||||

| Political empowerment [PE] | pe1 | 0.881 | 0.839 | 0.799 | 0.792 |

| pe2 | 0.862 | ||||

| pe3 | 0.842 | ||||

| Self-efficacy [SFY] | sfy1 | 0.860 | 0.886 | 0.821 | 0.802 |

| sfy2 | 0.842 | ||||

| sfy3 | 0.810 | ||||

| sfy5 | 0.780 | ||||

| Family support [FS] | fs1 | 0.873 | 0.792 | 0.832 | 0.864 |

| fs2 | 0.859 | ||||

| fs4 | 0.832 | ||||

| fs5 | 0.822 | ||||

| Women empowerment [WE] | we1 | 0.872 | 0.762 | 0.782 | 0.855 |

| we4 | 0.844 | ||||

| we2 | 0.840 | ||||

| we3 | 0.828 |

| CMIN/df | NFI | CFI | GFI | AGFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.493 | 0.902 | 0.911 | 0.922 | 0.910 | 0.035 |

| H/No. | Relationships | Path Co-Efficient | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | EE→WE | 0.388 | 6.672 | *** |

| H2 | SE→WE | 0.332 | 7.382 | *** |

| H3 | PE→WE | −0.080 | −1.081 | 0.280 |

| H4 | SFY→WE | 0.303 | 5.392 | *** |

| H5 | FS→WE | 0.120 | 4.382 | *** |

| H/No. | Relationships | Path Co-Efficient | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H6a | EE→SFY→WE | 0.209 | 3.872 | *** |

| H6b | SE→SFY→WE | 0.102 | 3.004 | *** |

| H6c | PE→SFY→WE | 0.071 | −1.001 | 0.672 |

| H7a | EE→FS→WE | 0.222 | 3.008 | *** |

| H7b | SE→FS→WE | 0.329 | 4.023 | *** |

| H7c | PE→FS→WE | 0.120 | 3.920 | *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Rashdi, N.A.S.; Abdelwahed, N.A.A. The Empowerment of Saudi Arabian Women through a Multidimensional Approach: The Mediating Roles of Self-Efficacy and Family Support. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416349

Al-Rashdi NAS, Abdelwahed NAA. The Empowerment of Saudi Arabian Women through a Multidimensional Approach: The Mediating Roles of Self-Efficacy and Family Support. Sustainability. 2022; 14(24):16349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416349

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Rashdi, Norah Abdullatif Saleh, and Nadia Abdelhamid Abdelmegeed Abdelwahed. 2022. "The Empowerment of Saudi Arabian Women through a Multidimensional Approach: The Mediating Roles of Self-Efficacy and Family Support" Sustainability 14, no. 24: 16349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416349