Innovation and Optimization Logic of Grassroots Digital Governance in China under Digital Empowerment and Digital Sustainability

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Research Design

2.1. Research Methodology

2.2. Data Sources

3. Visual Analysis

3.1. Post-Analysis

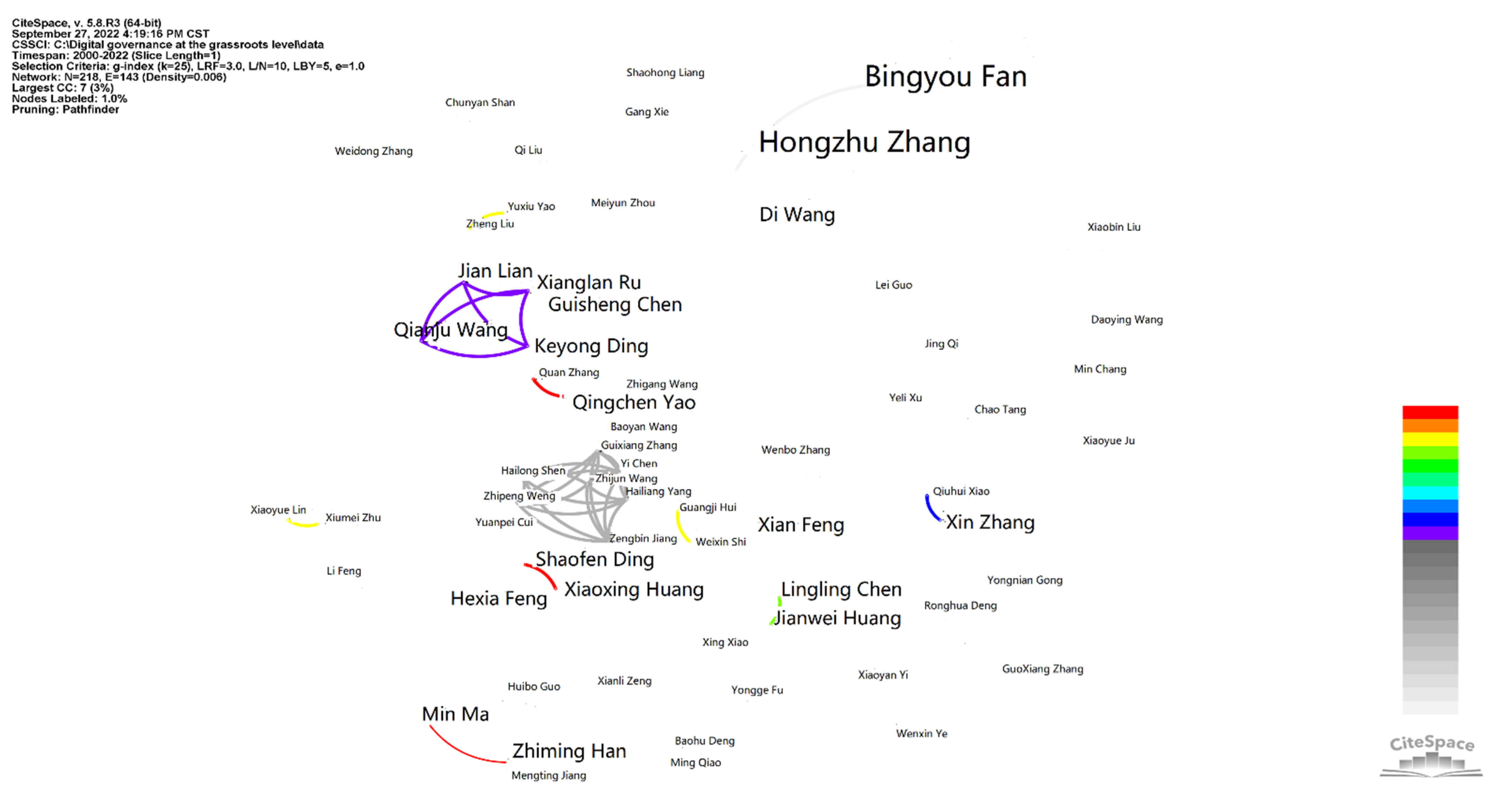

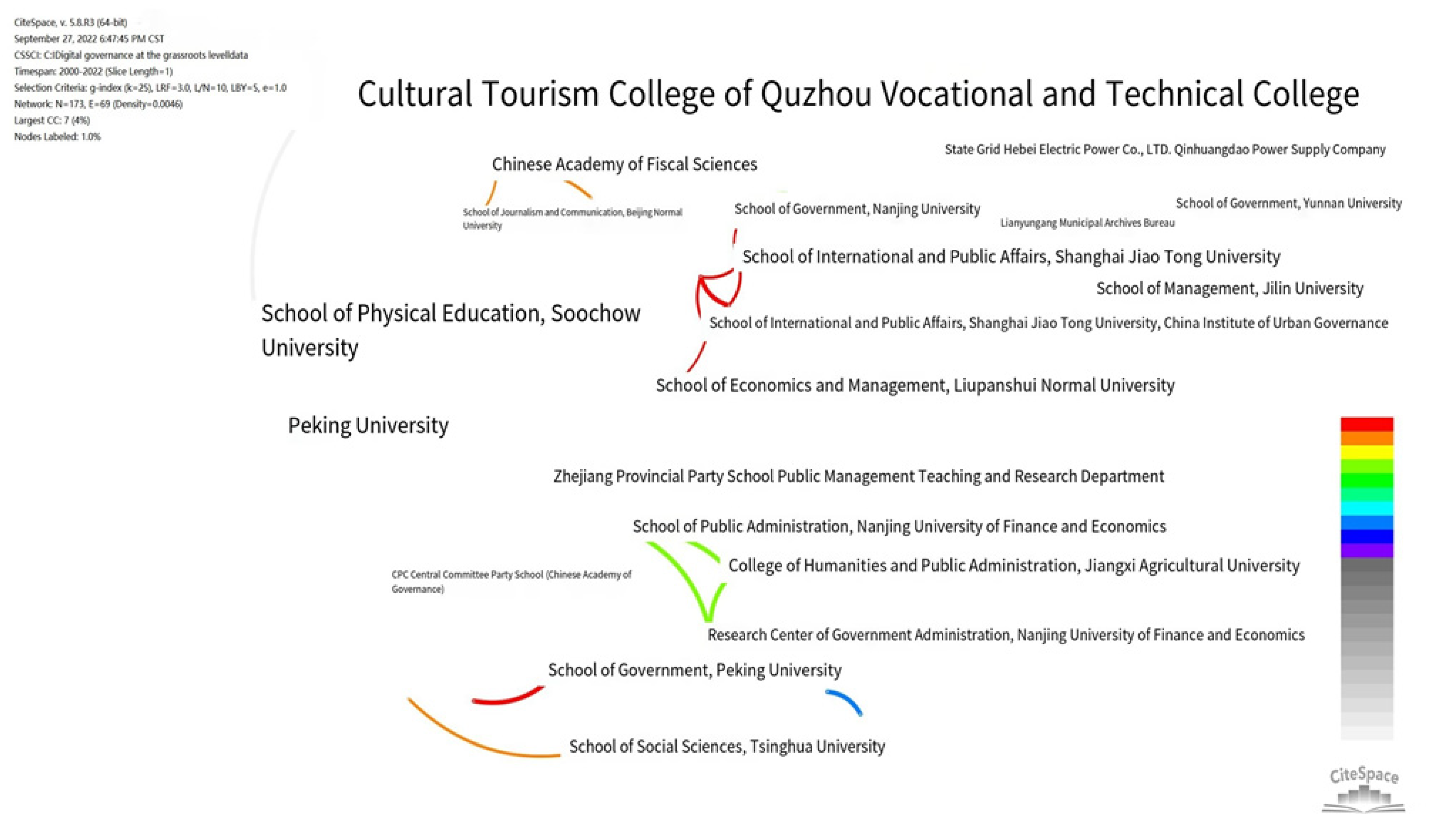

3.2. Analysis of Research Subjects and Cooperation Networks

3.3. Analysis of Research Hotspots

3.3.1. Keywords Co-Occurrence Analysis

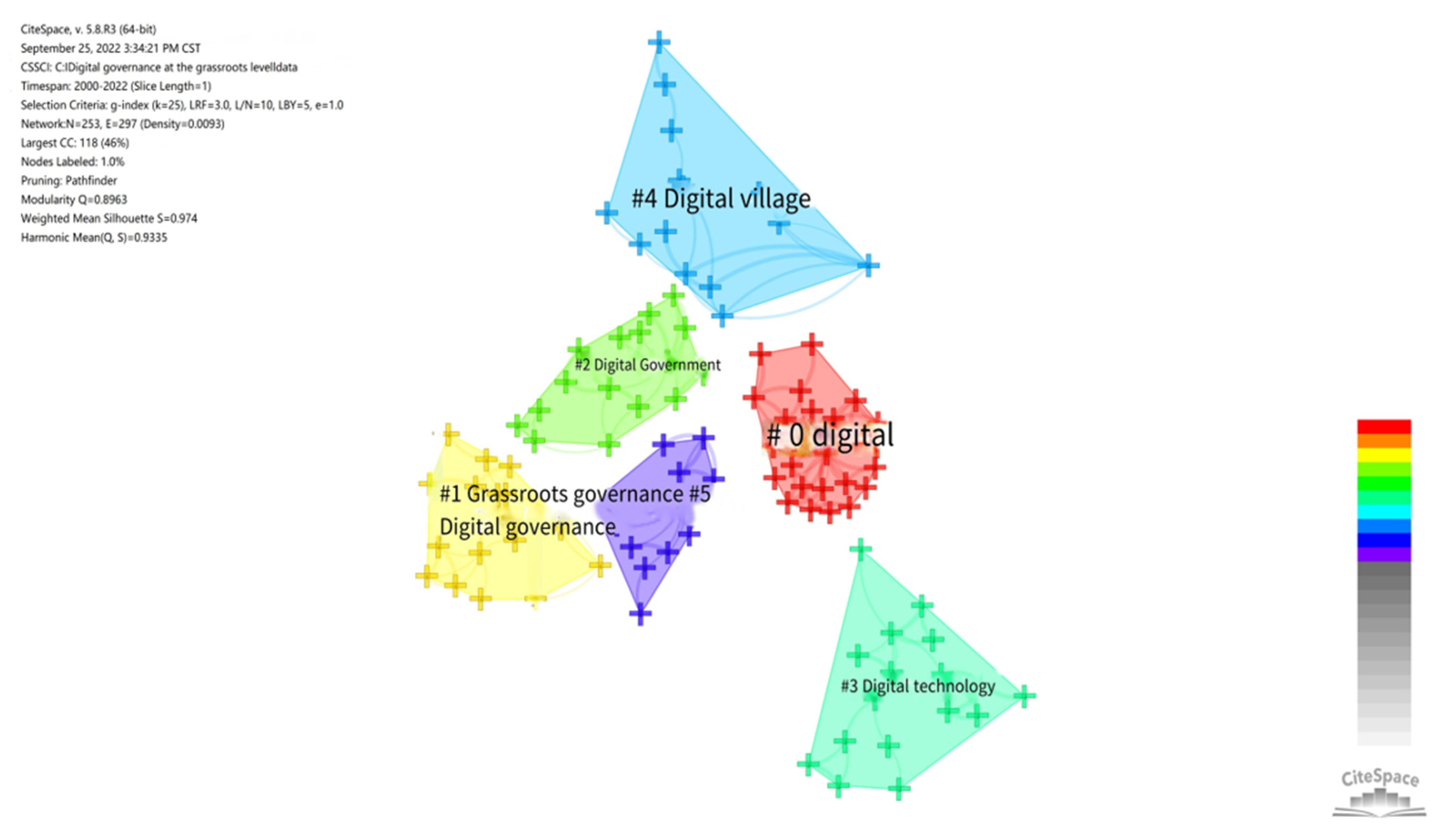

3.3.2. Keyword Cluster Analysis

3.4. Research Frontier Analysis

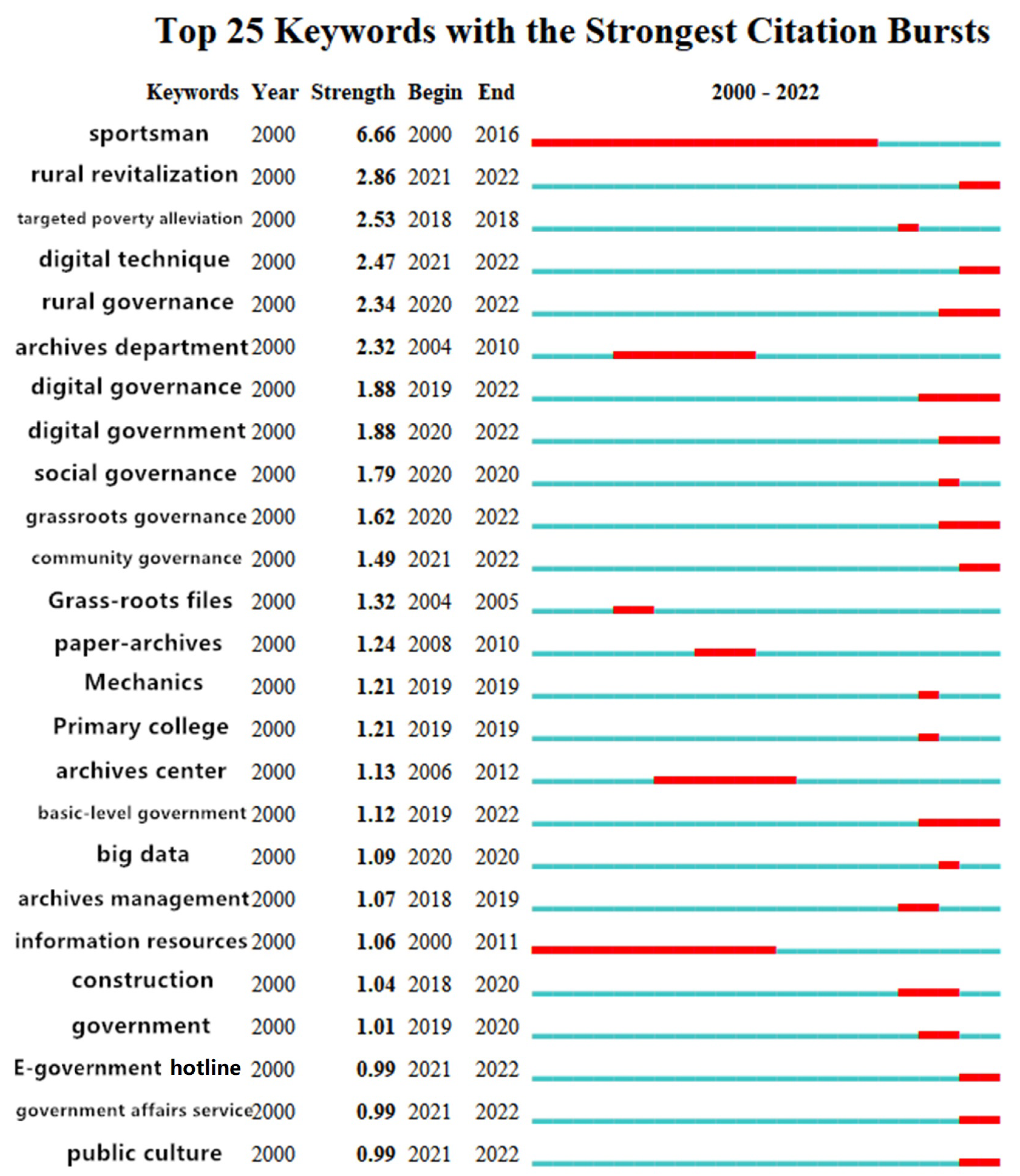

3.4.1. Statistical Analysis of Emergent Words

3.4.2. Time Zone Analysis

3.4.3. Timeline Analysis

3.5. Analysis of Highly Cited Literature

3.5.1. Research Topic Analysis

3.5.2. Emotional State Analysis of Research Literature

3.6. Analysis of Research Content

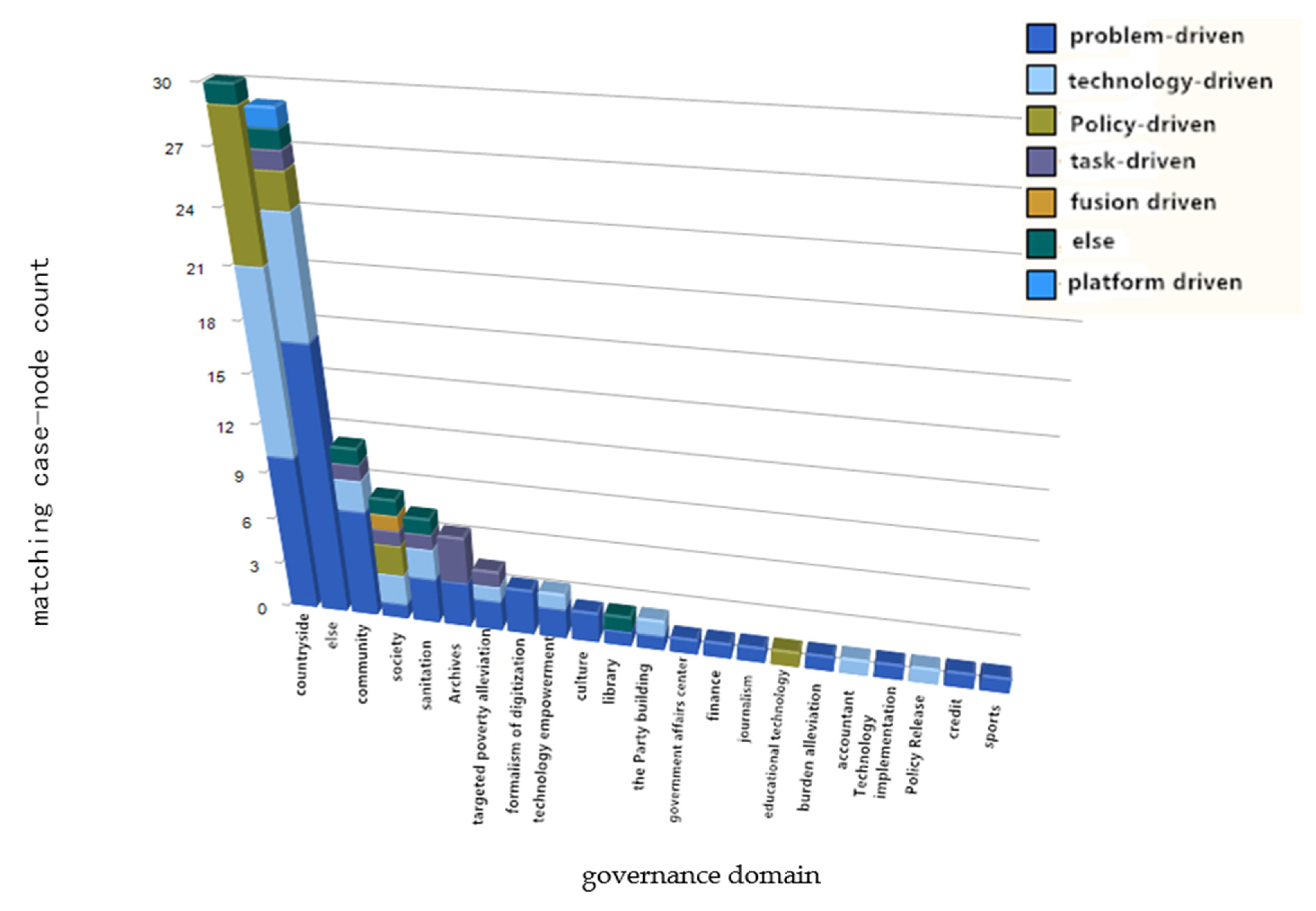

3.6.1. Literature Research and Analysis under the Dimension of Governance Domain-Driving Factors

3.6.2. Literature Analysis under the Governance Domain–Governance Logic Dimension

3.6.3. Driving Factors—Analysis of the Literature under the Governance Logic Dimension

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The number of “grassroots digital” publications in China exhibits an increasing trend. Chinese scholars attach great importance to grassroots digital governance research, and the research prospects of grassroots digital governance are broad.

- (2)

- There is a lack of communication and cooperation among the research subjects of “grassroots digitalization” in China, and a cooperative network with close and benign interaction has not yet been formed.

- (3)

- Research hotspots on grassroots digitalization in China are mainly focused on digitalization, digital governance, grassroots governance, rural governance, digital countryside, digital government, digital technology, rural revitalization, and grassroots government.

- (4)

- In terms of the categories of research hotspots, the research hotspots of grassroots digitalization in China are mainly focused on digitalization, grassroots governance, digital government, digital technology, and digital countryside.

- (5)

- From a research perspective, in the next few years, grassroots digital governance research has great potential. Rural revitalization, digital technology, rural governance, digital governance, digital government, grassroots governance, community governance, grassroots government, government hotline, government services, and public culture will continue to be hot topics of grassroots digital research in China.

- (6)

- With respect to the evolution trend, the digital research hotspot, with respect to the construction of information resources and digital archives management at the grassroots level, involves e-government phase shifting, and is characterized by the integrity of digital governance at the grassroots level of the digital government stage. Sharing of electronic governance will be the main characteristic of the phase transformation. At present, digital governance is moving towards a new stage of “digital-wise governance” characterized by digital empowerment and technology empowerment.

- (7)

- China’s highly cited papers focus on governance, digital management, and grassroots management, including government management and technical management. Scholars have mainly focused on these subjects, meaning that domestic research regarding basic digital governance has been focused on the realization of basic digital technology questions through extensive research and discussion. Research focusing on grassroots governance needs to be strengthened.

- (8)

- Chinese researchers have carried out a certain emotional orientation study on grassroots digitalization. Overall, a rational emotional attitude toward grassroots digitalization governance is dominant, and there is an optimistic tendency, which indicates that grassroots digitalization is in the transition period and has a large development space and good prospects.

- (9)

- With respect to the research literature content over nearly three years, rural and community are the foundations of the grassroots governance unit. These are the main fields of grassroots governance, and are also the basic digital governance areas. In addition to country and community, basic digital governance in China involves many aspects, such as Party, Science, Education, Culture and Health et al, suggesting that along with the transformation of China’s economic and social development, all walks of life are giving full play to the leading role of Party construction. At the same time, digital transformation is in full swing, and we expect to achieve high-quality development in digital transformation. In addition, “problem driven” has become the main driving factor of grassroots digital governance in China. Given that social, cultural, and other grassroots governance involve multiple attributes of complex activities and processes, in the field of technology the different governance involve the interaction of various elements. Their organic use includes technology management, innovation management, and governance theory, and the practical management of mixed logic is, at present, China’s basic digital management method.

5. Prospects

5.1. Strengthen the Integrated Governance of Grassroots Digital Systems

5.2. Improve the Ability to Solve Digital Governance Problems

5.3. Progressive Transformation of Grassroots Digital Governance Should Be Promoted by Incremental Governance Logic

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, W.; Wang, Q. Holistic Transformation of grassroots governance: Ecology, Logic and Strategy. J. Shenzhen Univ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2022, 39, 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, B.; Liu, X. Solving the collaborative problem of grassroots governance: The block-integrated path of digital platform. Theory Reform 2022, 3, 42–56. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Feng, H. Digital Health Community empowers change in health governance at the grassroots level. Adm. Reform 2022, 8, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.-X.; Ding, S.-f. Grassroots governance structure and Government Data Governance: A case study of grid management and special action in T District of Z City. Rev. Public Adm. 2002, 15, 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, B.; Liu, X. Obscuring Fuzzy Affairs with digitization: Technology enabling mechanism of grassroots governance. Xuehai 2022, 3, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Xuan, X. The Mission, Challenge and Countermeasure of Public Library in the Promotion of “National Reading”—A case study of the promotion of reading in Ningbo Library. Library 2022, 6, 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J. Operation logic and promotion strategy of digital rural governance—Based on the investigation of “Longyoutong” platform. Hubei Soc. Sci. 2022, 3, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.; Lu, X. Experience Exploration of digital platform participating in the construction of smart community—A case study of “Jinji5i”. Media 2022, 1, 68–69. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, W. Research on Agile grassroots governance in Megacities driven by the reform of government hotline: A case study of “12345” government hotline in Beijing. Leadersh. Sci. 2021, 16, 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H. The path to promote the modernization of credit Governance with wise governance—Zhejiang’s experience based on the digitization of credit construction. Chin. J. Credit Res. 2021, 39, 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Men, I.; Wang, C. “Internet + Grassroots Governance”: The digital realization path of grassroots holistic governance. e-Government 2019, 4, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Du, W. Research on the Digital transformation of Grassroots Social Governance—Based on the analysis of the practical experience of M City in the east of our country. Inf. Theory Pract. 2021, 44, 109–114+63. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Lin, X.; Wang, T. Research on Construction of grassroots community digital Emergency management system. Soft Sci. 2020, 34, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W. “Internet + Grassroots Governance”: Promoting holistic governance through digital means. Leadersh. Sci. 2020, 10, 30–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Q. The necessity and path analysis of digitization of grassroots Party construction. Peoples Forum 2019, 15, 106–107. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Chen, B.-l. Governance Dilemma, Digital Empowerment and Institutional Supply—The realistic logic of the digital transformation of grassroots governance. J. Theory 2022, 1, 144–151. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.; Ma, M. The tension between clarity and ambiguity and its adjustment: Focusing on the digital transformation of urban grassroots governance. Acad. Res. 2022, 1, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D. Digital Governance of urban grassroots society. J. Hubei Inst. Adm. 2011, 2, 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Zhong, X. Practice of paper archives digitization in basic archives room. Shanxi Arch. 2015, 5, 67–68. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. Problems and countermeasures of digitization of grassroots archives management. Archives 2010, 5, 59–60. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Liang, D. Discussion on Digitization Way of grassroots library. Telecommun. Technol. 2000, 1, 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S. The urgency, challenge and breakthrough of the digital transformation of grassroots governance. Leadersh. Sci. 2021, 12, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. Thinking and Innovation of the digital transformation of grassroots social governance. Leadersh. Sci. 2021, 14, 40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X. Exploration on the digitization reform of grassroots finance—A case study of A City in Zhejiang Province. Local Financ. Res. 2021, 4, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, L.; Song, S. Investigation on the use of digital telemedicine equipment in primary medical institutions in Guizhou Province. Mod. Prev. Med. 2021, 48, 1826–1829. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Lv, X. Research on the grass-roots government information disclosure mode of digital transformation from the perspective of rural revitalization. Agric. Econ. 2021, 10, 65–66. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zhong, L. The impact of digital transformation of grassroots social governance on digitally disadvantaged groups and its countermeasures. Leadersh. Sci. 2022, 10, 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, R. “Understanding people” do “understanding things”, and “Five members” cooperate to solve the problems of grassroots governance. Friends Peo. 2022, 8, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Li, T.; Liu, X.; Wang, D. Investigation and analysis of digitization construction of basic hospitals in Guizhou Province. Chin. J. Crit. Care Emerg. Med. 2022, 34, 863–870. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, L.; Zhang, M. Grassroots digital formalism and its collaborative governance of blocks. Acad. Exc. 2022, 8, 148–159. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X. Current situation and optimization strategy of digital transformation of grassroots social governance. Hunan Soc. Sci. 2022, 5, 80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Guo, N.; Mao, Z.; Yao, H. A Study on the policy Guidance of Digitization Reform of grassroots Government Affairs Service—A case study of Longhua District Government Affairs Service Center of Haikou City. J. Public Adm. 2022, 19, 150–165+176. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Lim, J.-A.; Nam, H.-K. Effect of a Digital Literacy Program on Older Adults’ Digital Social Behavior: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cingolani, L.; Hildebrandt, T. Incentive Structures for the Adoption of Crowdsourcing in Public Policy: A Bureaucratic Politics Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burinskienė, A.; Seržantė, M. Digitalisation as the Indicator of the Evidence of Sustainability in the European Union. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, M.; Mandru, L. A Model for a Process Approach in the Governance System for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.; MacLachlan, M.; Marshall, K.; Morahan, N.; Carroll, C.; Hand, K.; Boyle, N.; O’Sullivan, K. Including Digital Connection in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: A Systems Thinking Approach for Achieving the SDGs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dima, A.; Bugheanu, A.M.; Dinulescu, R.; Potcovaru, A.M.; Stefanescu, C.A.; Marin, I. Exploring the Research Regarding Frugal Innovation and Business Sustainability through Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, D.V.; Dima, A.; Radu, E.; Dobrotă, E.M.; Dumitrache, V.M. Bibliometric Analysis of the Green Deal Policies in the Food Chain. Amfiteatru Econ. 2022, 24, 410–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjimah, H.P.; Atiase, V.Y.; Dzansi, D.Y. Examining the Role of Regulation in the Commercialisation of Indigenous Innovation in Sub-Saharan African Economies: Evidence from the Ghanaian Small-Scale Industry. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, C.M. CiteSpace: Text Mining and visualization in Science and Technology; Capital University of Economics and Business Press: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Zeng, S.; Zhong, M. NVivo 11 and Network Qualitative Research Methodology; Wunan Book Publishing Co., Ltd.: Taipei, Taiwan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H. Research Group, Peking University. Platform-driven Digital Government: Capabilities, Transformation, and modernization. e-Government 2020, 7, 2–30. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, M. Absorption and management of poverty alleviation: The suspension in the implementation of targeted poverty alleviation policies and the predicament of grassroots governance. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2018, 18, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, G. Enterprise digitization, specialized knowledge and organizational empowerment. China Ind. Econ. 2020, 9, 156–174. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, X.; Wanyan, D.D. Practice research on promoting equalization of basic public cultural services by digitization. Libr. Work. Res. 2016, 8, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.; Li, J.; Cui, K. Digitization of rural governance: Current situation, Demand and Countermeasures. e-Government 2020, 6, 73–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z. Is it possible for the government to be a platform?—A case study of collaborative governance digital practice. Gov. Res. 2020, 36, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, C.-R.; Xu, H.-y. Practical dilemmas and breakthrough paths of current digital rural construction. J. Yunnan Norm. Univ. Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2021, 53, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C. Governance of “Data Governance”—Starting from the governance phenomenon of “civilized code”. Leg. Sci. J. Northwest Univ. Political Sci. Law 2021, 39, 58–70. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Q.; Zhang, X. People’s livelihood archives work in grassroots Archives: Current situation, problems and countermeasures. Commun. Arch. Sci. 2014, 2, 96–100. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S. The Grand Practice of public digital cultural Resources Construction—The current situation and development of National cultural information Resources Sharing Project Resource construction. Libr. J. 2015, 34, 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Sun, X.; Dai, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, B. Policy Analysis on Recycling of Solid Waste Resources in China-Content Analysis Method of CNKI Literature Based on NVivo. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Dai, X.; Zhang, B.; Sun, X.; Liu, B. Development and Path of Reclaimed Water Utilization Policy in China: Visual Analysis Based on CNKI and WOS. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Sun, X.; Dai, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, B. Knowledge Map Analysis of Industry–University Research Cooperation Policy Research Based on CNKI and WOS Visualization in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Serial Number | Author | Article Number | Start Year | Author | Article Number | Start Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hongzhu Zhang | 22 | 2000 | Lingling Chen | 2 | 2019 |

| 2 | Bingyou Fan | 20 | 2000 | Qingchen Yao | 2 | 2021 |

| 3 | Jian Lian | 3 | 2013 | Guisheng Chen | 2 | 2022 |

| 4 | Xianglan Ru | 3 | 2013 | Shaofen Ding | 2 | 2022 |

| 5 | Keyong Ding | 3 | 2013 | Xian Feng | 2 | 2020 |

| 6 | Qianju Wang | 3 | 2013 | Jianwei Huang | 2 | 2019 |

| 7 | Xin Zhang | 2 | 2013 | Xiaoxing Huang | 2 | 2022 |

| 8 | Hexia Feng | 2 | 2021 | Di Wang | 2 | 2011 |

| 9 | Min Ma | 2 | 2022 | Chao Tang | 1 | 2021 |

| 10 | Zhiming Han | 2 | 2022 | Daoying Wang | 1 | 2011 |

| Institutions | Article Number | Start Year | Institutions | Article Number | Start Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School of Cultural Tourism, Quzhou Vocational and Technical College | 21 | 2000 | Nanjing University of Finance and Economics School of Public Administration | 2 | 2019 |

| School of Physical Education, Soochow University | 21 | 2000 | School of International and Public Affairs, Shanghai Jiao Tong University | 2 | 2022 |

| School of Government, Nanjing University | 3 | 2019 | Qinhuangdao Power Supply Company of State Grid Hebei Power Co., LTD | 2 | 2013 |

| Peking University | 3 | 2011 | Chinese Academy of Fiscal Sciences | 2 | 2021 |

| School of International and Public Affairs, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China Academy of Urban Governance | 2 | 2022 | School of Social Sciences, Tsinghua university | 2 | 2021 |

| Lianyungang Municipal Archives Bureau | 2 | 2013 | Yunnan University School of Government | 2 | 2020 |

| Nanjing University of Finance and Economics Research Center for Government Administration | 2 | 2019 | School of Management, Jilin University | 2 | 2019 |

| School of Information Management, Wuhan University | 2 | 2014 | College of Humanities and Public Administration, Jiangxi Agricultural University | 2 | 2019 |

| Teaching and Research Department of Public Administration, Party School of Zhejiang Provincial Committee of the Communist Party of China | 2 | 2020 | School of Government, Peking University | 2 | 2021 |

| School of Journalism and Communication, Beijing Normal University | 2 | 2021 | CPC Central Committee Party School (Chinese Academy of Governance) | 2 | 2021 |

| Keywords | Count | Centricity | Year | Keywords | Count | Centricity | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digitalization | 24 | 0.29 | 2004 | Archives | 4 | 0 | 2004 |

| Sportsman | 19 | 0 | 2000 | Construction | 4 | 0 | 2011 |

| Digital governance | 13 | 0.05 | 2019 | Digital empowerment | 4 | 0.01 | 2022 |

| Grassroots governance | 11 | 0.11 | 2018 | Information technology | 4 | 0.03 | 2013 |

| Rural governance | 11 | 0.07 | 2020 | Targeted poverty alleviation | 4 | 0.03 | 2018 |

| Digital countryside | 11 | 0.02 | 2020 | Big data | 3 | 0.01 | 2020 |

| Digital government | 10 | 0.08 | 2018 | Collaborative governance | 3 | 0.05 | 2020 |

| Digital technology | 10 | 0.1 | 2020 | Community governance | 3 | 0.01 | 2021 |

| Rural revitalization | 9 | 0.01 | 2021 | Public service | 3 | 0.21 | 2010 |

| Grassroots government | 6 | 0.04 | 2019 | Basic unit | 3 | 0 | 2014 |

| Label | Number of Nodes | Outline of the Value | Year | Keywords |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 25 | 1 | 2015 | Digital (18.61, 1.0 × 10−4); Power and responsibility relationship (3.31, 0.1); Zhejiang (3.31, 0.1); Collaborative governance (3.31, 0.1); Government as a platform (3.31, 0.1) |

| 1 | 17 | 0.996 | 2019 | Grassroots governance (15.85, 1.0 × 10−4); Targeted poverty alleviation (7.78, 0.01); Institutional supply (3.86, 0.05); Precise identification (3.86, 0.05); Urban grassroots Party building (3.86, 0.05) |

| 2 | 17 | 0.964 | 2019 | Digital government (15.29, 1.0 × 10−4); Digital literacy (3.94, 0.05); Information society (3.94, 0.05); Simplicity and efficiency (3.94, 0.05); Overall governance (3.94, 0.05) |

| 3 | 17 | 0.954 | 2020 | Digital technology (13.8, 0.001); Interembedding governance (4.5, 0.05); Health poverty alleviation (4.5, 0.05); Emergency management (4.5, 0.05); Grassroots community (4.5, 0.05) |

| 4 | 16 | 1 | 2019 | Digital country (13.8, 0.001); Rural revitalization (6.79, 0.01); Community governance (6.79, 0.01); Information technology (6.79, 0.01); Agile governance (6.79, 0.01) |

| 5 | 12 | 0.898 | 2018 | Digital governance (11.13, 0.001); Public services (7.78, 0.01); Public sector (3.86, 0.05); Digital formalism (3.86, 0.05); Grassroots governance innovation (3.86, 0.05) |

| Serial Number | Article | Author | Citation (Times) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Platform-driven digital government: Capabilities, Transformation and Modernization [43] | Research Group, Peking University, Huang Huang | 125 |

| 2 | Absorption and governance of poverty alleviation: Suspension in the implementation of targeted poverty alleviation policies and difficulties in grassroots governance [44] | Yuan Mingbao | 99 |

| 3 | Enterprise digitization, proprietary knowledge and organizational empowerment [45] | Liu Zheng, Yao Yuxiu, Zhang Guosheng, Kuang Huishu | 72 |

| 4 | Practical research on promoting the equalization of basic public cultural services through digitalization [46] | Xiao Ximing, Wanyan Deng | 72 |

| 5 | Digitalization of rural governance: Research on current situation, demand and countermeasures [47] | Xian Feng, Li Jin, Cui Kai | 61 |

| 6 | Is “government as a platform” possible?—A case study of collaborative governance in digital practice [48] | Hu Chongming | 44 |

| 7 | Practical dilemmas and breakthrough paths of current digital countryside construction [49] | Feng Chaorui, Xu Hongyu | 41 |

| 8 | The governance of “data governance”—starting from the governance phenomenon of “civilized code” [50] | Guo Chunzhen | 40 |

| 9 | Livelihood Archives Work in grassroots archives: Research on current situation, problems and countermeasures [51] | Xiao Qiuhui, Xin Zhang | 37 |

| 10 | Grand practice of public digital cultural resources Construction—Current situation and development of national cultural information resources sharing project resources construction [52] | Chen Shengli | 35 |

| Serial Number | Node | Reference Points | Serial Number | Node | Reference Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | governance | 406 | 11 | social | 201 |

| 2 | digital | 380 | 12 | culture | 197 |

| 3 | information | 281 | 13 | organization | 188 |

| 4 | resources | 274 | 14 | enterprise | 174 |

| 5 | service | 255 | 15 | grassroots | 170 |

| 6 | data | 255 | 16 | rural | 166 |

| 7 | construction | 222 | 17 | development | 149 |

| 8 | government | 221 | 18 | work | 142 |

| 9 | technology | 214 | 19 | management | 140 |

| 10 | digitization | 203 | 20 | platform | 134 |

| Serial Number | Document Name | Very Negative | More Negative | More Positive | Very Positive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C01 | Platform-driven digital Government: Capabilities, Transformation, and Modernization | 44 | 46 | 143 | 5 |

| C02 | Absorption and governance of poverty Alleviation—Suspension in the implementation of targeted poverty alleviation policies and difficulties in grassroots governance | 51 | 21 | 82 | 1 |

| C03 | Enterprise digitization, proprietary knowledge and organizational empowerment | 40 | 57 | 50 | 3 |

| C04 | Practical research on promoting the equalization of basic public cultural services through digitalization | 9 | 14 | 47 | 1 |

| C05 | Digitalization of rural governance: Current situation, Needs and Countermeasures | 19 | 9 | 46 | 1 |

| C06 | Is’ government as a platform’ possible—With a case study of governance digitization practices | 33 | 24 | 68 | 1 |

| C07 | Practical dilemmas and breakthrough paths of current digital countryside construction | 35 | 27 | 77 | 0 |

| C08 | The Governance of “Data Governance”—Starting from the governance phenomenon of “civilized code” | 64 | 48 | 123 | 1 |

| C09 | Current situation, Problems and Countermeasures of People’s Livelihood Archive Work in Grassroots Archives | 2 | 6 | 18 | 0 |

| C10 | The grand construction of public digital cultural resources…Enjoy the current situation and development of engineering resources construction | 8 | 5 | 64 | 4 |

| Total | 305 | 257 | 718 | 17 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Zhan, G.; Dai, X.; Qi, M.; Liu, B. Innovation and Optimization Logic of Grassroots Digital Governance in China under Digital Empowerment and Digital Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16470. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416470

Li J, Zhan G, Dai X, Qi M, Liu B. Innovation and Optimization Logic of Grassroots Digital Governance in China under Digital Empowerment and Digital Sustainability. Sustainability. 2022; 14(24):16470. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416470

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Junjie, Guohui Zhan, Xin Dai, Meng Qi, and Bangfan Liu. 2022. "Innovation and Optimization Logic of Grassroots Digital Governance in China under Digital Empowerment and Digital Sustainability" Sustainability 14, no. 24: 16470. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416470

APA StyleLi, J., Zhan, G., Dai, X., Qi, M., & Liu, B. (2022). Innovation and Optimization Logic of Grassroots Digital Governance in China under Digital Empowerment and Digital Sustainability. Sustainability, 14(24), 16470. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416470