1. Introduction

Traditionally, Cambodian farmers work together in agriculture, in line with a vital principle of agricultural cooperatives (ACs). The earliest ACs, managed by the Royal Office of Cooperatives Cambodia, were established during the 1950s and 1960s. The operation of ACs was effective, and a recorded trade turnover was then an estimated 13 million USD in 1965 [

1]. The Khmer Rouge dismantled ACs in 1970 and took the nation after a civil war between 1975 and 1979. ACs were forced into collective labor [

2]. In 1979, the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime collapsed, and ACs were reestablished as Krom Samaki (solidarity groups) in the 1980s. Krom Samaki worked to compensate for the shortage of materials needed for agricultural activities to help the poorest people. Moreover, Krom Samaki contributed to efforts of revolution to share rice with the military and civil servants. In 1985, Krom Samaki was dissolved when the Royal Government of Cambodia (RGoC) announced the land ownership distribution program [

3].

On 16 July 2001, the Royal Decree on the establishment and functioning of ACs, the union of the ACs and the pre-agricultural cooperatives was enacted to address the operation of inactive ACs during the demise of the Khmer Rouge regime [

4]. Moreover, the Law on Agricultural Cooperatives came into force on 9 June 2013, which required all ACs to register with the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF). The purpose of the enforcement of this law was to support farmers in enhancing agricultural production and in creating job alternatives, empowering them to improve their socio-economic status and self-reliance [

5]. Nou (2006) [

6] distinguished differences between ACs and farmer associations (FAs). An FA is defined as a profitable enterprise which is democratically supervised by its members, who contribute their investment capital and expect dividends, and it agrees to incur losses based upon the proportion of its contributed shares. An AC, a local association, is a group of natural persons prearranged by Khmer citizens to pursue a mutual purpose, serving its members’ material or moral interests without searching private earnings. According to the Law on Local Associations and Non-Government Organizations (NGOs), the establishment of FAs is required to register with the Ministry of Interior (MoI) [

7]. This study analyzes the roles of ACs and local engagement in supporting agricultural development under the management of the MAFF.

However, ACs are formed by local people. NGOs have recently played significant roles in providing technical and financial support to establish and operate Community-Based Organizations (CBOs). Farmer members under ACs can work independently on community development. Moreover, they diversify crops based on farmers’ locations and living conditions. ACs and their farmer members paved the way for the RGoC and NGOs to access and support smallholder farmers to improve food security and poverty reduction [

8]. ACs positively impact community development and immensely contribute to livelihood; their primary functions are facilitating supply, marketing and technical farming techniques [

1]. Moreover, ACs support their farmer members in terms of credit, with low interest rates, effort savings and agricultural inputs. In communities, ACs play a crucial role in forming common interests among a group of people to assist each other through collective bargaining power between villagers and buyers [

9].

However, ACs have a long history of establishment since 1965 over different regimes; Cambodia’s ACs remained in a very early stage compared with its neighboring countries, such as Vietnam and Thailand. Therefore, the MAFF promotes the implementation of the Agricultural Sector Master Plan 2030 (ASMP 2030), which has developed an auspicious method to update Cambodia’s agriculture. ACs operations are one of the government’s commitments to transfer the widespread traditional subsistence agricultural system to diversify production, develop a value chain and value added [

10]. This paper aims to analyze local engagement in ACs operations in Cambodia by focusing on (1) the degree of participation in ACs operations; (2) factors influencing local engagement in ACs operations; and (3) the challenges and constraints of ACs operations to support communities. This research poses the following three questions: How do farmer members participate in ACs operations? What factors influence local engagement in ACs operations? Why are ACs struggling to operate to support local livelihood effectively?

2. Conceptualizing ACs in Cambodia

In the Asian Pacific, ACs have been utilized to enhance socio-economic constraints and to enhance weak agriculture management among smallholder farmers [

9]. ACs have created collective work [

11] among smallholder farmers to improve productivity [

12] and to generate income-generation activities [

13,

14]. Wiggins et al. (2010) [

15] argued that collective actions help farmers access agricultural services and investment capital to enhance production systems. In developing countries, smallholder farmers are motivated to engage in ACs operations for innovative decision-making processes for crop quality and risk management [

16,

17], for technological transfers and adaptations [

18,

19,

20,

21] and for long-run market power and networks [

22,

23,

24], especially direct sales to local markets [

25]. According to Stockbridge et al. (2003) [

26], farmer members can access market information, loans and deposit savings from ACs. Moreover, they undergo skill-building and internal quality control to improve their crop productivity [

27]. However, measuring the income contribution of farmer members from the assistance of ACs operations is not easy; however, farmers are beneficial to ACs operations [

9].

During the late 19th century, modern ACs were initially established in Europe and were widely introduced in industrializing nations as a self-help method to reduce poverty and for food security [

28]. In developing countries, such as Africa, farmer members participate in ACs operations to increase their productivity at the micro-level and to enhance food security at the macro-level [

29]. ACs, with assistance from the government through subsidized interest rates, tax concessions and prices, have aided commercial agriculture as suppliers of farmers’ inputs, as a marketing network of their products through boards and as service providers [

30]. ACs have successfully contributed to food processing and marketing for milk, sugar in Argentina and Brazil, and oil seeds in India [

28]. Spielman et al. (2008) [

31] confirmed that ACs have a positive impact on advertising smallholder cereals in Ethiopia for commercialization. However, this regional-specific impact varies depending on whether ACs are established through the collective action of their member base or through NGO intervention.

Existing studies have recorded AC failures in developing countries concerning inputs and markets for product suppliers [

28]. Available local capacity is the main causes of failures [

32]. Appropriate government assistance and a stable legal environment are essential for successful ACs operations [

33]. Crowley et al. (2005) [

34] recognized the crucial roles of ACs as grassroots membership-based organizations capable of financial and managerial self-reliance. In Africa, ACs have repeatedly failed, owing to issues of being not accountable to their members and causing unsuitable political actions or financial wrongdoings in management [

35]. According to Van Niekerk (1988) [

36], the failures of ACs in South Africa were caused by limited management experience and knowledge, insufficient investment capital and unfaithfulness of their members. In Cambodia, the MAFF has developed the agriculture sector development strategy for 2030, which envisions converting agriculture in Cambodia into an inclusive, modern, competitive, climate-resilient and sustainable sector, attempting to promote farmers’ income, well-being and prosperity [

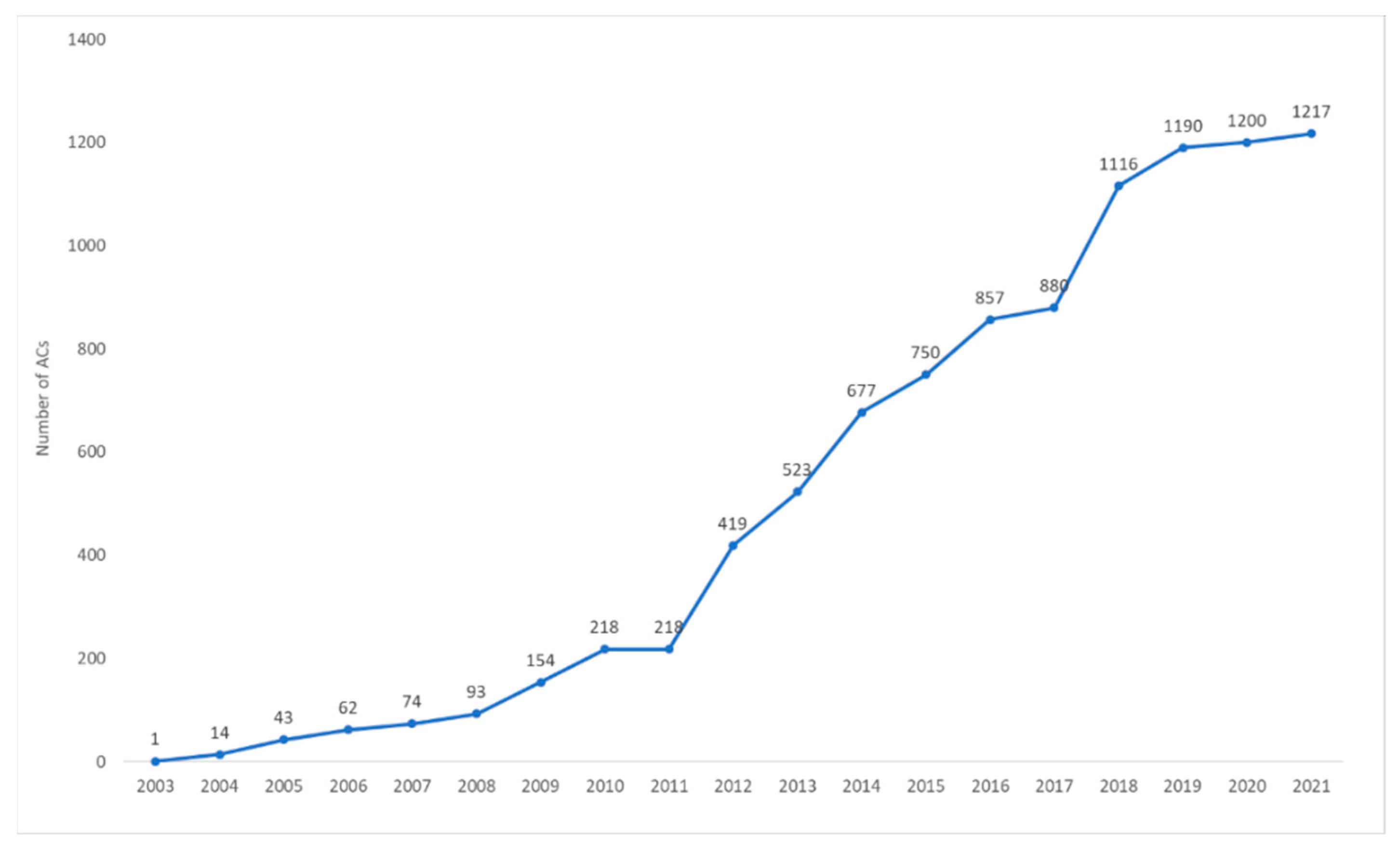

37]. The establishment of ACs across the country has gradually increased from 1 AC in 2003 to 1217 ACs in 2021. They mainly work to improve saving services and the supply of agricultural inputs, such as seeds and fertilizers (

Figure 1).

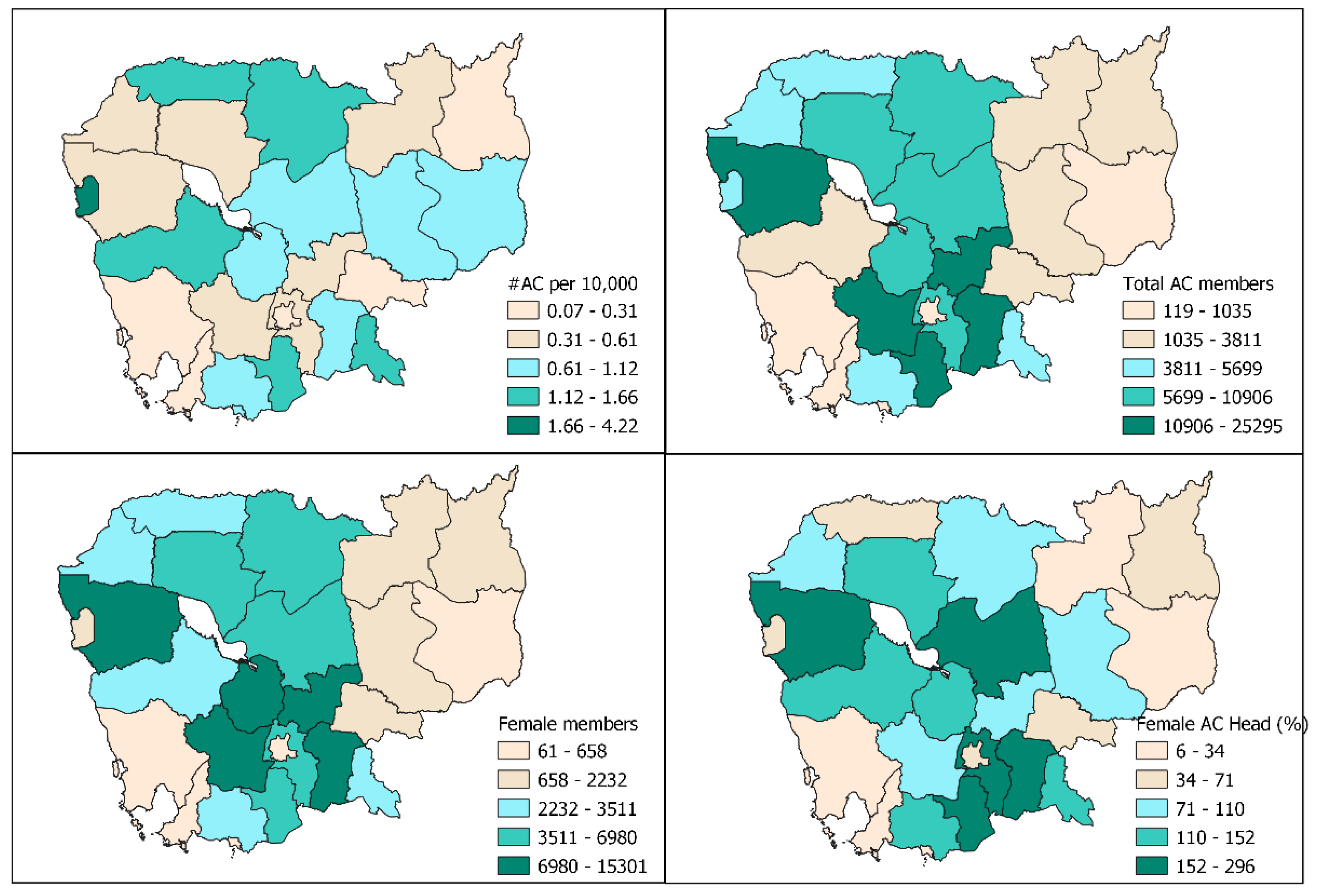

By 2020, there were 144,306 members, including 90,603 females and 53,703 males. However, 62.8% of the total members were female; only 39.5% of women were elected as chairmen and members of the board of directors to operate ACs [

38] (

Figure 2). In line with the government strategy, the MAFF’s vision is to empower farmers to jointly develop resources sustainably, acquire experience and transfer knowledge. The MAFF works with private sectors and inspires them to be comprehensive, competitive and cooperative in an open market to achieve producer power in their business partnerships with buyers through agreements [

39]. Moreover, ACs operations remain a focus of support for several development partners and donors such as the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) and the World Bank [

4]. Both government and development partners believe that the establishment of ACs is the best option to assist smallholder farmers because ACs can operate with a wide range of business scopes falling under the agricultural sector, such as agricultural production, agri-business, the agri-industry and farming support services for farmers [

37].

In this research, the following hypothesis is formulated: “Engagement in ACs operations is associated with access to agricultural inputs, access to water resources, benefits from ACs, participation in ACs activities, risk control and ACs management”. The existing literature shows that engagement in ACs operations is associated with management [

40,

41], daily AC tasks [

42], participation in AC activities [

43], benefit for farmers’ socio-economic development [

44], access to inputs, productivity and product markets [

45,

46], and access to water resources [

47].

3. Materials and Methods

The fieldwork was conducted between February and May 2022. Both primary and secondary data and information were gathered for a critical analysis of local engagement in ACs operations in Cambodia. Secondary raw data regarding the number of ACs and boards of directors and members between 2003 and 2021 by provinces were obtained from the MAFF and were used for the analysis of trends and mapping. Household surveys for quantitative data were carried out to gather primary data, and participatory tools, including key informants, in-depth interviews and group discussions, were organized to collect qualitative data. The Barseth district of Kampong Speu province and the Bakan district of Pursat province were recruited for this research. The selection of the two provinces was informed by discussion with NGOs, boards of directors of ACs and local authorities of the two provinces. The two selected provinces shared a similar status regarding the number of ACs (55 in Kampong Speur and 60 in Pursat). This recruitment provided an opportunity to investigate the local engagement of farmer members in ACs operations. A total of 421 farmer members were selected for the interviews: 212 in the Barseth district and 209 in the Bakan district. Further interviews were conducted with government officials, NGOs, farmer members and AC boards of directors (

Appendix A). In each district, one focus group discussion was organized among ten farmer members equally shared by male and female farmer members to identify problems and to obtain a consensus regarding local engagement in ACs operations. The interviews and focus group discussions for qualitative data were primarily held in the wake of the quantitative data analysis produced by the survey.

For quantitative analysis, Weight Average Index (WAI), t-tests and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) were used. We used WAI to measure on a five-point scale, for example, to explore the satisfaction of farmer members concerning ACs operations. The five-point scale included the following: very dissatisfied (VD) = 0.00–0.20, dissatisfied (D) = 0.21–0.40, moderate (M) = 0.41–0.60, satisfied (S) = 0.61–0.80 and very satisfied (VS) = 0.81–1.00. This research proceeded in three stages to test the proposed research hypotheses. Firstly, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) with SPSS 25 was operated to classify the underlying variables of engagement in ACs operations, agricultural inputs, water resources, benefits from ACs operations, participation in ACs operations, risk control and management. Secondly, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was run to perform a statistical test on how well the measured variables represented the constructs and to confirm the model’s goodness of fit. Thirdly, the analysis of relationships among local engagement, agricultural inputs, water resources, benefits from ACs operations, participation in ACs activities, risk control and management were applied to empirically test using the SEM implication with AMOS 23. The process of three stages of data analysis was helpful for the verification of the reliability and validity of the variables and the contents of questionnaire item.

Exploratory Factor Analysis and reliability tests were conducted by using the principal component method with VARIMAX rotation. This technique helps run factor analysis and reliability tests for verifying variables’ dimensionality and reliability. Various purification processes, such as factor analysis, correlation analysis and internal consistency analysis (Cronbach’s Alpha:

), were confirmed by the research. Factor analysis was initially run to classify the dimensionality of each item. Theoretically, the threshold of the factor loading score of each item must be higher than 0.60. Moreover, the Alpha (

) coefficient and the item-total correlation were applied to observe the reliability and internal consistency of the primary study construct. According to Hair et al. (2014) [

48], the factor loading of each item must be larger than 0.60, the eigenvalue must be larger than 1, the cumulative percentage must be higher than 60%, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value must be higher than 0.50, the item-total correlation must be greater than 0.50 and the Alpha (

) coefficient must be higher than 0.60 or 0.70. The threshold of each criterion of factor analysis and the reliability test is illustrated in

Table 1. Some items have been removed if factor loadings were less than 0.60. This process facilitated upsurging the cumulative percentage of factor analysis to fit the threshold value and increased the reliability test’s Cronbach’s alpha.

As shown in

Table 1, rules of thumb were adopted to evaluate the factor analysis and the reliability test results indicated in

Table 2. However, some research items were deleted because they did not meet the threshold values. Indeed, some research items were deleted due to containing a value of factor loading lower than the criterion of 0.60. Most importantly, the rest of the research items of the formal reliability test were adopted to double-confirm the CFA and to test the research hypotheses with SEM by utilizing AMOS 23 software.

The results of the correlation matrix shown in

Table 3 designate the correlational relationship among the variables. The procedure of using a correlation matrix was aimed at using all variables from the formal factor analysis and reliability test stage. The results reveal that some variables have a significant relationship. This finding indicates that the relationship between “management” and “risk control” has the highest correlation, which is 0.766 (or 76.6%) (i.e., the significance level of a

p-value less than 0.01). Secondly, “local engagement“ has a high correlation with “participation,” which is 0.697 (or 69.7%). However, other relationships shown in bold are not significant.

LOE = Local Engagement

AGI = Agricultural Inputs

WAR = Water Resources

BEN = Benefits from ACs operations

PAT = Participation of ACs activities

RIC = Risk Control

MAN = Management

In this research, the construct validity was calculated by means of the guidelines of Anderson and Gerbing (1988) [

49]. First, this study ran exploratory factor analysis by extracting factors with varimax methods and reliability tests to treat the reliability and validity of all research variables. Thus, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were larger than 0.60 for each factor. Secondly, we ran CFA to measure the convergent validity. Confirmatory Factor Analysis contains two main parts: (1) a First-Order Factor Model and (2) a “Second-Order Factor Model [

50,

51]. This research accepted the first-order factor model to individually observe the research construct, as shown in the results in the

Appendix A and

Appendix B. The threshold values of CFA and SEM, as revealed in

Table 4, were accepted to assess the results of CFA and SEM (as shown in

Table 4). The results of the first-order factor model show that all the threshold values are satisfied (refer to

Figure A1,

Figure A2,

Figure A3,

Figure A4,

Figure A5,

Figure A6 and

Figure A7). Therefore, the second-order factor model was accepted to observe the overall model’s fitness. Moreover, all loadings exceeded 0.60, and each indicator’s t-value exceeded 1.96 (

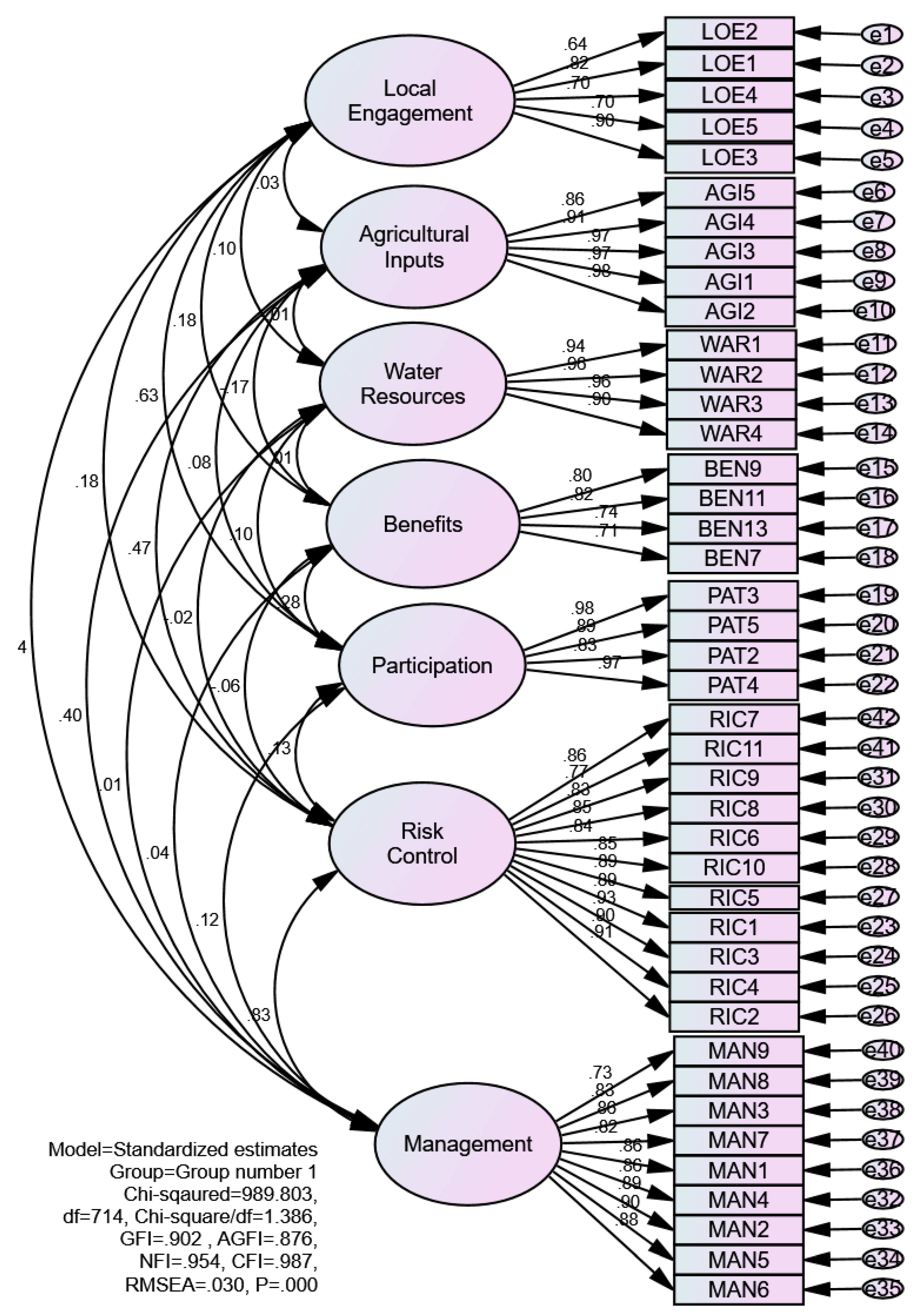

p < 0.05), which signified the satisfaction of the CFA criteria. As shown in

Table 5 and

Figure 3, the overall assessment of the goodness-of-fit displayed that χ

2/df = 1.461, GFI = 0.902, AGFI = 0.876, NFI = 0.954, CFI = 0.987 and RMSEA = 0.030. The results specify that the model presents a good fit with acceptable convergent validity. When all values were more significant than the established cutoff criteria, the research proceeded with hypothesis testing using SEM. The threshold of CFA and SEM was accepted to assess the findings of this research, as shown in

Table 5.

LOE = Local Engagement

AGI = Agricultural Inputs

WAR = Water Resources

BEN = Benefits from ACs operations

PAT = Participation in ACs activities

RIC = Risk Control

MAN = Management

An SEM was used to perform statistical tests on how well the measured items represented a set of theoretical latent factors. For a study with more than 419 respondents and a questionnaire of 37 measurement items, the leading fit indices operated to assess the CFA/SEM model. The model consisted of expected

p-values for the Chi-squared test (<0.001), Comparative Fit Index (CFI > 0.92), Standardized Root-Mean-Square Residual (RMR < 0.08) and Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA < 0.07) [

48]. Other fit indices included the goodness-of-fit statistic and the adjusted goodness-of-fit statistic (GFI, AGFI > 0.9: good, 0.8–0.9: acceptable); the Root-Mean-Square Residual (RMR < 0.08); Incremental Fit Indices (IFI > 0.9); and the Parsimony Goodness-of-Fit Index and the Parsimonious Normed Fit Index (PGFI, PNFI > 0.5) (Hooper, Coughlan and Mullen, 2008). To increase the model statistic fit assessment of GFI and AGFI, scholars have argued that GFI and AGFI must be derived from sample sizes of between 100 and 500 respondents. Moreover, the GFI and AGFI values must be higher than the threshold value, ranging from 0.80 to 0.90 [

50,

51]. The goodness-of-fit in the model reveals that the observed data are suitable or consistent with the theory or model used for the statistical test. The GFI measures the relative number of variants and covariates, with a magnitude ranging from 0 to 1 [

48]. In this research, the goodness-of-fit of the model demonstrates that the observed data are appropriate or consistent with the theory or model to be statically tested. If the value is close to 0, the model has a low fit. If the value is close to 1, the model has the best fit. The modification index (MI) was set to >4.0 by default and can be adjusted to increase the model statistic fit index for both CFA and SEM [

55,

56]. The results of this research show that GFI = 0.902, AGFI = 0.876, NFI = 0.954, CFI = 0.987 and RMSEA = 0.030. Therefore, the proposed model is considered good and is considered an appropriate and acceptable model in this research.

We applied the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and Composite Reliability coefficients (CR) to relate the quality of the measures. It is essential to appropriately comprehend the equations of the AVE and CR and their associations with the definitions of validity and reliability to avoid misconceptions. In this research, we explain, using simulated one-factor models, how the number of items and the homogeneity of factor loadings are influenced by the results of AVE and CR.

where λ (Lamda) signifies the standardized factor loading,

i is the number of items (1), δ (Delta) signifies error variance terms (2) and δ = 1 −

.

Based on the works of Fornell and Larcker (1981) [

54,

55,

56,

57] and Peterson and Kim (2013) [

59], AVE must be larger than 0.50, and CR must be larger than 0.70. Hair et al. (2014) [

48] explained that the t-value must be larger than 1.96 and that the

p-value < 0.05. All other criteria illustrated in

Table 4 are also required to assess the results of CFA and SEM. “Local Engagement” has AVE = 0.574 and CR = 0.87; “Agricultural Inputs” has AVE = 0.81 and CR = 0.97; “Water Resources” has AVE = 0.84 and CR = 0.96; “Benefits from ACs’ operation” has AVE = 0.59 and CR = 0.85; “Participation in ACs’ activities” has AVE = 0.84 and CR = 0.96; “Risk Control” has AVE = 0.75 and CR = 0.97; and “Management” has AVE = 0.72 and CR = 0.96. The AVE must meet the threshold to satisfy the overall model fit assessment, which has a good fit in terms of NFI = 0.954 > 0.950 and CFI = 0.987 > 0.950.

4. Results

4.1. Local Engagement in ACs Operations and Their Contribution to Their Livelihood

In 2002, the RGoC approved ACs operations under the management of the MAFF to improve socio-economic status and to reduce poverty among smallholder farmers. The Department of Agricultural Cooperative at the General Directorate of Agriculture is a responsible agency for providing technical and financial support to the communities for establishing and operating ACs [KI-1, per communication]. These CBOs have worked with smallholder farmers to run and own their businesses by increasing agricultural production and revenues [KI-2, per communication]. An AC chairman in Pursat claims that the establishment of ACs created space for local engagement and provided employment opportunities to enhance members’ social, cultural and economic positions. At the community level, ACs helped smallholder farmers form groups to create agricultural economic initiatives, expand agricultural production and share knowledge [Interview 1, per communication].

Every five years, farmer members elect boards of directors during general meetings; they are the executive bodies of ACs. ACs also organize annual meetings to approve new memberships and acknowledge anyone leaving these CBOs. Boards of directors consist of fewer than 15 members, and any villager aged 18 years old and above is eligible to run for election. They, including the chairman and vice chairpersons, voluntarily provide managerial operations and monitoring/evaluation positions for ACs with support from their members [KI-1, per communication]. According to the AC chairman in Kampong Spuer, ACs mobilized and accumulated capital through shares and delivering services, such as saving schemes, fertilizer trading and livestock raising/trading [Interview 3, per communication]. In Takeo, farmer members at Champa Prey Pdoa Community Collection Center were eligible to invest as shareholders of, with around 24.5 USD per share. Local investments have led to an increase in value for shareholders if they ever choose to withdraw their shares [KI-3, per communication].

The results from fieldwork show that ACs in Pursat and Kampong Speur carried out daily tasks and activities to support their farmer members in accessing agricultural inputs, markets and loans for investment. They organized monthly meetings among farmer members to discuss issues and to exchange knowledge to improve agricultural productivity. Moreover, they worked with NGOs to mobilize resources for skill building and highly productive rice and crop seeds. The AC chairman in Pursat appealed that local engagement was crucial to supporting ACs operations. ACs operations depend primarily on financial and human resources mobilizing among their members and funds from NGOs. ACs’ revenues are not high enough to cover daily operating costs to deliver daily services without support from NGOs and their members [Interview 2, per communication].

As a result, as seen in

Figure 4, the household survey found that farmer members had a low degree of engagement with other farmer members and had a very low degree of involvement in ACs operations. Engagement in ACs operations helped farmer members share knowledge, transfer technology, exchange agricultural inputs and crops, and access loans or savings. Farmers could more conveniently work with other members because they shared a similar socio-economic status [KI-4, per communication]. For ACs operations, farmer members rated very low degrees of their participation in meetings organized by AC boards of directors (WAI = 0.13), in voluntary work with ACs (WAI = 0.12), in voluntary work with NGOs (WAI = 0.06) and in voluntary work with government agencies (WAI = 0.05). The t-test analysis confirmed that respondents in Kampong Speu shared higher degrees of engagement than did those in Pursat regarding meetings organized by boards of directors (

p-value = 0.000), voluntary work with NGOs (

p-value = 0.000) and voluntary work with government agencies (

p-value = 0.000). In contrast, respondents in Pursat assessed higher degrees than its counterpart regarding voluntary work with ACs in supporting their functions (

p-value = 0.000).

During the survey, farmer members shared their interests in ACs operations because their overall purpose was to increase the local economy through skill building, agricultural inputs and access to loans, savings and markets. The mission of ACs is to provide financial, practical and technical assistance within agricultural communities. Moreover, ACs have been established to support their members in advancing technical knowledge, skills and know-how in producing chemical-free and high-value vegetables and livestock and to associate their members in the market. Group discussions showed that AC members were primarily interested in getting involved in specific activities directly beneficial to income generation, such as skill building, group saving, capital investment and access to agricultural inputs and markets. They were not much interested in engaging in leadership or managing ACs operation, for example, with meetings organized by AC boards of directors and voluntary work with ACs, NGOs and government agencies. In most cases, farmer members did not accept invitations and did not participate as they were assigned because of business reasons and income-generation activities [FDG-1, per communication].

Since the 2020s, NGOs have been the primary sources of funds and capital for establishing and operating ACs. However, the establishment of ACs received legal and policy support through their registration with the MAFF. NGOs initiated and built the capacity of boards of directors and raised awareness among smallholder farmers to get involved in ACs. An AC chairman revealed that NGOs supported ACs in developing by law and in forming the board of directors [Interview 3, per communication]. Moreover, NGOs worked to facilitate between the MAFF, the Provincial Office of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (PoDAFF), Commune Councils (CoCs), boards of directors and members. NGOs supported ACs operations by providing agricultural inputs and technology transfers. Development projects have assisted ACs operations in promoting organic productivity by providing farming techniques to deal with the risks and vulnerabilities incurred by climate change. NGOs have provided climate-smart agricultural practices and revolving funds among farmer members to improve seeds and soil [KI-4, per communication]. An NGO officer mentioned that NGOs believe that farmer members continue helping each other to raise livestock, unify their communities and to increase their income and consumption. With support from NGOs, ACs have helped farmer members increase investment capital and have provided agricultural inputs and loans. ACs have also allowed their members to improve skills in diversifying the productivity of crops and livestock and in market and advanced technological transfers [KI-4, per communication].

4.2. Factors Influencing Local Engagement in ACs Operations

SEM was applied to statistically test the hypothesis that “local engagement is associated with agricultural inputs, water resources, benefits from ACs operations, participation in ACs operation, risk control and management” with the likelihood estimation method. Variables remained the same after the CFA, as illustrated in

Table 6; they were accepted to run SEM for statistically testing the method of livelihood estimation. The second-order factor model was recruited to perform a statistical test of the overall variables [

54,

57]. The results confirmed the goodness-of-fit measurements to be acceptable (GFI = 0.905, AGFI = 0.880, NFI = 0.955, CFI = 0.988 and RMSEA = 0.028) (

Table 6 and

Figure 5). The model also shows that the proposed model results in a satisfactory goodness-of-fit assessment [

48]. CFA used similar variables, as demonstrated in

Table 6. The model ran before proceeding with SEM to statistically test the likelihood estimation method. The SEM model discloses that local engagement in ACs operations did not have a significant impact on access to agricultural inputs, which yielded β = 0.058,

p = 0.259 (

p > 0.05) and t-value = 1.129 (t-value < 1.96). In contrast, the model confirms that local engagement in ACs operations had a significant positive relationship on access to water resources (β = 0.106 **,

p = 0.040 < 0.05 and t-value = 2.051 > 1.96), benefits from ACs operations (β = 0.190 ***,

p = 0.000 < 0.001 and t-value = 3.472 > 1.96), participation in ACs activities (β = 0.632 ***,

p = 0.000 < 0.001 and t-value = 15.662), risk control (β = 0.197 ***,

p = 0.000 < 0.001 and t-value = 3.765) and ACs management (β = 0.147 **,

p = 0.005 < 0.05 and t-value = 2.791).

The group discussion in Kampong Spue revealed that ACs could not supply heavy agricultural machinery, such as tractors, mobile threshing machines and plow machines. AC members could access small-scale loans of a few hundred dollars from the saving group scheme. Available loan amounts could not be used to purchase necessary agricultural machinery. However, AC members could access seeds and traditional equipment, such as spades, shovels, cow bars, pickaxes, axes, hoes and hod baskets. Farmers were required to seek the possibility of purchasing heavy machinery by themselves; they mainly took loans from banks for them. The AC chairman in Pursat described the critical contribution of NGOs in supporting local people to engage in ACs operations; they provided high-productivity seeds and various types of traditional equipment. Moreover, ACs played a crucial role in increasing access to water among their members because it is an essential source for their agriculture-related activities. In the Samlot district of Battambang, a woman engaged in ACs operations to gain support to access water. Water is essential for villagers to grow crops and raise livestock. ACs worked to help villagers to access sufficient water for their crops and livestock [Interview 6 per communication].

I understand well the importance of water for garden and livestock raising. Water in the pond dries out if there is no rain. So, I have to use a pump to fill the water in the pond. Since water from the water pump includes limestone, I cannot directly water the vegetables from the pump. Water from the well consists of limestone and causes the death of vegetables. I pump ground water from the well into the pond to supply sufficient water for vegetables. I can use water for my vegetables after three days of storing them in the pond.

The model estimates that 63.0% of farmer members engaged in ACs operations because they wished to participate in the activities to promote their products and to access markets and loans. Factors such as risk control (20.0%), benefits from ACs operations (18.0%) and ACs management (15.0%) also contributed to local engagement in ACs operations accordingly. Discussion among the members showed that farmers were interested in engaging with ACs that were effectively operated and managed. The reputations of boards of directors were very influential to ACs members because they revealed their capacity to lead ACs operations. There were cases of AC failures and bankruptcy, and boards of directors left those communities [KI-2, per communication]. A member described the advantages and disadvantages of ACs management and leadership; members benefitted highly from their activities and services. Boards of directors with high competency could build good relationships with local government agencies, NGOs and people to mobilize financial and human resources to increase agricultural productivity, market access and finance. Moreover, a transparent and accountable board of directors could mobilize external and domestic resources to operate ACs.

The MAFF, ACs and farmer members similarly understood the essential contributions of NGOs in promoting ACs operations. Moreover, the MAFF has support schemes for investing between 250 and 500 USD in ACs. An officer indicated that an AC is at risk if it is highly dependent on external actors and has a weak capacity to operate this CBO. There was no evidence to certify that a successful AC must be established with support from the government, NGOs or communities. Some ACs functioned healthily because they had good management and because farmer members engaged in their operations. Commitment from the boards of directors is also critical to successfully operating ACs. Moreover, ACs need clear business plans, good connections with buyers and teamwork with farmer members [KI-2 per communication].

4.3. Challenges and Constraints of ACs Operations to Support Communities

In Cambodia, ACs are involved in rice, animal and vegetable production. Local people have operated them with some support from the MAFF and NGOs. Therefore, they have limited business plan development, entrepreneurship, and leadership resources and capacity, but they do not have sufficient finances to invest in agricultural inputs and production systems [KI-2 per communication]. Overall, ACs have faced various challenges and issues in their operations.

Table 7 indicates a moderate degree of poor management, inadequate capital accumulation, loan mismanagement, a lack of skilled personnel, unavailable loans, high illiteracy levels among members, small share values, a lack of access to credit facilities, access to the competitive market and a lack of support from agricultural extensions. Farmer members rated low degrees of challenge in developing business plans.

Every year, boards of directors and their members develop their business plans through participatory approaches. However, ACs develop annual plans with support from NGOs or the MAFF; their goals cannot be fully or effectively implemented. In Takeo, ACs faced difficulties planning crops because rainfall changed. This AC board of directors and its members could not effectively plan which crops could be grown during the rainy or dry season. More water was in the dry season, and there was less water in the rainy season. Growing cucumbers, wax gourds, Chinese spinach and Taiwanese bok choy cabbage is good in the dry season because they do not need much water. However, crops such as cassava, maize and sugarcane are more suitable in the rainy season because they require more water. Climate change has caused changes in water partners, so ACs cannot adequately plan which crops should be grown in dry or wet seasons. An NGO officer claimed that farmers were safer growing crops in the dry season because they can use underground water even if they cannot access wetlands. All crops must be destroyed if a flash flood is caused by heavy rain or a river flood [KI-4, per communication].

ACs struggled to negotiate with buyers to make contracts for stable prices. There were two issues with contracts between ACs and buyers. Many buyers did not wish to have any agreement with ACs. Buyers preferred to come and buy according to their daily demands, and they did not want to set the quantity and quality of the crops. In addition, buyers only had contracts for cheaper crops, so farmers were unhappy with the price. Buyers were willing to collect cheaper crops in the markets, and farmers accepted the offers by reducing quality using fertilizers or chemicals. Many farmers opted not to follow the standards when buyers dropped prices lower than those in the market [KI-2, per communication]. On the other hand, ACs could create contracts with buyers under the conditions of a set amount that ACs could collect daily, but they did not dare not to set how much suppliers would need.

ACs had concerns with their members about the quantity and quality of crops produced to meet the buyers’ demands and conditions. Since ACs could not ensure timeliness and that enough crops were provided for suppliers, they dared not to create contracts with suppliers. For example, an AC in Takeo sought an agreement with buyers between 15,000 USD and 20,000 USD, but this AC could supply vegetables and fruits between 2000 and 3000 USD per month. The volume of vegetables and chicken produced under ACs management is handy for dealing with buyers. Currently, ACs have limited capacity to seek big-scale buyers; most likely, they are intermediaries. In this light, ACs should work with agricultural extension units and NGOs to seek bigger-scale buyers with contracts to ensure constant prices for the long-term process of marketing procedures [KI-3, per communication].

Interviews with the MAFF and NGOs similarly revealed that boards of directors managed and operated the ACs; they were less-educated residents. ACs did not have sufficient skilled personnel, so their knowledge, skills and competency were insufficient to effectively and efficiently manage ACs. On the other hand, ACs did not receive sufficient support from local authorities, primarily in terms of finance. However, some ACs’ boards of directors and members were Commune Council (CoC) members. However, annual commune investment plans (CIPs) included only prioritized actions with no budget for their implementation. In the communities, intermediaries played a significant role in supplying agricultural products in terms of quantity, quality and market access [FGD, per communication]. The availability of financial resources from shares was still limited for the investment and expansion of their business. Moreover, ACs remained reliant on NGOs and government agencies to improve their physical infrastructures, such as market halls. In Takeo, Heifer International funded the Champa Prey Pdoa Community Collection Center to construct collection centers where ACs and their members stored their products for suppliers [KI-3, per communication].

5. Discussion

5.1. The Causes of Low Engagement in ACs Operations

Today, there are nine farmer organizations in Cambodia, including Farmer Groups, Farmer Communities, Farmer Associations, ACs, Farmer Federations, Farmer Water User Communities, Producer Cooperatives or Producer Organizations, Self-help Groups or Savings Groups, and Contract Farming [

60,

61,

62,

63,

64]. They support farmers with different activities, from market bargaining power to capacity building. Different purposes drive the establishment and operation of farmer organizations, but they are not necessarily mutually exclusive from one another. For instance, AC members may also join in contract farming [

65]. Different governmental agencies manage farmer organizations; for example, ACs are under the MAFF. The Farmer Water User Group operates under the Ministry of Water Resources and Meteorology (MOWRAM), as the name suggests, and it may also involve saving activities and producer groups [

66].

Local engagement is the heart of ACs operations because farmer members can be on the board of directors, shareholders, producers and buyers. Officers from the MAFF and NGOs understood that the capacity and management of boards of directors remained key constraints to attracting local involvement in ACs operations. Local farmers operated ACs with limited knowledge, skills and capital to carry out daily tasks. The capacity and management of boards of directors could only help to perform activities to run a small-scale agricultural business. Moreover, farmer members did not have specific purposes and business plans when they engaged in ACs operations. ACs also help farmers to access loans for their investments through savings groups, but the amount is small. Farmer members who wish to access large amounts may need to go to a commercial bank with collateral and high interest rates. When their income from an investment cannot cover bank interest rates, they prefer to take small loans from savings groups. As a result, expectations of farmer members have not been reached to satisfy local engagement because it is not beneficial to operate under ACs to improve their livelihoods. During the Agricultural Summit 2022, smallholder farmers recognized the essential roles of ACs and local engagement. ACs require more attention for better access to agricultural inputs and finance for investments and markets for famers’ products. As a result, the RGoC should have a firm policy and commitment to promoting domestic products for national, regional and international markets [

67]. ACs should be operated to support an inclusive local economy by creating local jobs, increasing famers’ incomes and ensuring the country’s food security while meeting the recent constraints of climate change. During the focus group discussion in the Bakan district of Pursat, farmer members wished to have ACs that could help them provide their crops to buyers for better prices with contracts that specify clear quality and quantities. Farmer members are unhappy with intermediaries because they can drop fees and amounts of crops supplied at any time.

In Kampong Chhnang, the Krang Leav Samaki Agricultural Cooperative collected fees from its members, and revenues contributed to the AC’s operations. Moreover, farmer members gathered monthly to discuss issues and to share their experiences involving crops, livestock, markets and capital management. This AC assisted farmer members in accessing cheaper agricultural equipment, the market, business credit and skill building. In return, this AC helped maintain the price of their farm products. An AC member expressed high satisfaction with engagement in ACs, as follows [Interview 6, per communication]:

I am happy to pay the membership fee because the AC is helping to ensure stable prices of chicken and crops in the communities. For example, I can sell cucumbers up to USD 0.55 per kilogram during an earlier harvest. Moreover, I can sell the chicken for USD 4.25 per kg compared to the previous price of USD 3.00 and 3.80. I am happy to contribute USD 0.08 for each kilogram of chicken sold.

An AC member of the Samroh Kampong Lpov Agricultural Cooperative provided details for why she decided to get involved this agricultural cooperative [Interview 5 per communication].

In 2018, I started to get involved in activities carried out by the Samroh Kampong Lpov Agricultural Cooperative. The cooperative provided me with training for livestock raising and gardening. After training from the cooperative, I have changed business patterns, especially home gardening and chicken raising. Under the project, NGOs [DanChurchAid in Cambodia] gave me modern gardening and a credit of USD 500 for capital investment. Before support from the project, I also raised chickens and grew vegetables for my consumption only. With techniques, skills, knowledge and credits from the project, I became a self-employed businesswoman who earns a relatively good daily or monthly income from selling vegetables and chicken.

The improved role of collectively supplying crops for buyers to obtain reasonable prices has encouraged long-term local engagement and success for ACs. Evidence shows an emerging shift to implementing a cooperative principle in which all farmer members collectively work to supply their crops. By doing so, farmer members gain reasonable prices for their sales. Socio-economic development is significant for famer members involved in ACs operations when these CBOs play vital roles in promoting their socio-economic status through increased access to water resources, agricultural inputs and markets. According to CAFAP, because ACs register their farmer member, they have diversified multiple crops since 2010 and have collected crops from their members to collectively supply markets in Phnom Penh. For example, a group of 88 households, including 45 female households, sold their crops individually but started to collectively sell their crops, especially 300 kilograms of lemongrass per day in 2015 and 8–10 tons per day in 2019. In 2020, sales significantly dropped, and ACs challenged their access to the market due to the COVID-19 pandemic [

68].

Partnerships between ACs and the private sector have excellent potential for stable markets with reasonable prices, capacity building and access to agricultural inputs. An interview with Khmer Time News with Amru Rice’s CEO showed that, in 2021, the company renewed and expanded its contract farming agreement to 82 ACs throughout the country. This agreement directly benefited almost 10,000 farmer households to access markets for their products; the targets included poor farmers and indigenous people in remote upland regions. Partnerships between private sectors and ACs help to improve the livelihoods of farmers with disadvantaged backgrounds by empowering their capacity, giving incentives for organic rice, increasing productivity by 20% and raising income by 50% more than standard conventional practices [

69]. An NGO officer agreed that private partnerships between ACs and suppliers should be promoted because farmer members can sell their crops with final prices without transaction costs paid to middlemen. The MAFF officer also mentioned that private partnerships increase mutual trust between farmers and suppliers regarding quality and quantity. However, ACs still require support from the MAFF and NGOs to ensure that their agreement benefits farmers when they prepare legal documents and operations.

5.2. Support Mechanism Promoting ACs Operations

The latest ASMP 2030ASMP 2030 has become an auspicious method to update the country’s agriculture from an overall traditional agricultural system, lasting for several centuries. This plan aims to diversify agricultural production, to develop a value chain and value added. Therefore, the MAFF has mobilized resources to expand ACs operations because they needed to strengthen financial management, marketing management and skills in processing, packaging, transportation and storage [

37]. The MAFF has worked with development partners to establish and operate ACs nationwide based on a solid foundation to shape a modern market-oriented cooperative sector. To support government strategies, development partners have supported cooperative development. Although the FAO and JICA have helped in standalone projects, the IFAD and the World Bank assisted with more total value chain investments. Most projects supported by development partners and donors advocate for farmer peer educators and self-help groups.

For example, in ADB’s Emergency Food Assistance Project, 42 out of over 400 self-help groups were dissolved into ACs to undertake input supply, collective produce marketing and seasonal credit [

70]. The World Bank has provided a 30 million USD loan between 2019 and 2025 for the Cambodia Agricultural Sector Diversification Project (CASDP). The Ministry of Economic and Finance (MEF), through the Agriculture and Rural Development Bank, is the agency that enhances the agricultural sector by giving subsidiary loan agreements to micro-financial institutions and banks to help with financial access to the agricultural sector. This initiative aimed to endorse financial inclusion and to assist production chains and agricultural sector diversification in 13 capitals/provinces. The project covers Phnom Penh, Kampong Cham, Battambang, Stueng Treng, Mondulkiri, Ratanakiri, Tbong Khmum, Preah Vihear, Kratie, Siem Reap, Kandal, Kampong Chhang and Kampong Speu. Under the 30 million USD subsidiary loan agreement, the signed banks and MFIs will provide loans with an annual interest rate of 5 percent for farmers, small and medium enterprises, agricultural cooperatives and producers for all agricultural products except rice [

71]. The U.S. Government’s Feed the Future Initiative, supervised by USIAD or the U.S. Agency for International Development, has provided 25 million USD in funds for Harvest III between 2022 and 2027. The project aims to improve sustainable broad-based economic growth by promoting diversification and competitiveness in Cambodia’s agriculture sector. Harvest III has worked with private sectors, ACs, technology service providers and financial institutions to generate jobs, to train skilled workforce and to create market opportunities. The project’s purpose is to improve agricultural markets and to contribute to the livelihoods of women, youth and marginalized populations [

72].

An NGO officer revealed that development funding is channeled through government agencies and NGOs for activities to support ACs operations in Cambodia. In communities, the MAFF and NGOs with funds from development partners establish ACs and provide them with financial and technical support to operate those ACs. However, ACs mobilize internal capital for investment through shareholding; the funds that tare collected to handle the ACs remain very small. Cooperatives wish to collaborate with company leaders, financial institutions and the public sector to ensure sustainable farming for smallholders. Thus, farmer members have appealed to international donors and the public sector to work directly with farmer organizations in Cambodia, thus involving farmers directly in the funding source to improve their production in response to climate change and to overcome obstacles caused by COVID-19, both now and in the future. This will enable farmers, especially smallholder farmers, to obtain access to direct donations from donors, thus meeting increased demands for food in the coming years, especially by 2030 when the world plans to not leave someone behind in poverty and hunger, and by 2050, when food demand is estimated to increase to almost double.

5.3. Relationship between Local Engagement and Successful ACs Operations

Current studies specifically investigated the importance of access to agricultural inputs [

45], access to water resources [

47], the benefit to farmers’ socio-economic development [

44], participation in ACs activities [

42] and management [

17] for local engagement in ACs operations. The SEM confirms that local engagement in ACs operations is positively associated with access to water resources, benefits from ACs, participation in ACs activities, risk control and ACs management. Engagement in ACs operations does not significantly impact access to agricultural inputs. Overall, farmer members are active in the participation and operation of ACs when ACs management is good enough to benefit those members. Although this study confirms that farmer members had access to water sources for their crops, they were not accessible as agricultural inputs for their engagement. During fieldwork, farmers were motivated to participate in ACs operations because they wished to access agricultural inputs and water resources for their crops. ACs operations, with support from the MAFF and NGOs, involve building skills and advancing technology and equipment for increased productivity. Farmer members were also able to access water resources from nearby wetlands or underground water for their crops. However, ACs did not have sufficient funds to help farmer members access agricultural inputs and cumbersome machinery. Access to agricultural inputs is the main barrier for farmer members to increase their productivity and also is a challenge regarding motivating farmers to become members.

The latest 2020 study by the MAFF revealed that ACs in Cambodia have concentrated on credit, savings services and supplying agricultural inputs, such as seeds and fertilizers. The SEM recognizes participation in ACs activities as a key contributor to promoting local engagement. Moreover, daily tasks and ACs management are factors that attract farmer members to participate in ACs activities. Many ACs face challenges moving forwards because they do not have sufficient human and financial resources; they heavily depend on the support of government agencies and NGOs. In developing countries, such as Cambodia, ACs operations become inactive when they cannot help their farmer members access agricultural inputs [

28], such as heavy machinery. Local capacity and resources [

32], skills and technology [

36] and management [

35] remain the causes of failures. This research is aligned with the findings of [

34] Crowley et al. (2005) [

34], who recognize the significance of being capable of financial and managerial self-reliance. A remaining question is how to mobilize local financial capital for ACs investments and human capacity, which are the most challenging tasks and assignments of NGOs and government agencies for enabling the long-term operation and management of ACs. Famers are willing to actively engage in ACs operations when they see the benefits of membership. However, the success of ACs operations is required for local engagement in the establishment, involving boards of directors, shareholders, producers and buyers.

6. Conclusions

Based on our findings in Barseth district of Kampong Speu province and Bakan district of Pursat province, along with additional insight about the impacts of local engagement in ACs operations in Cambodia overall, we conclude the following: (i) Local engagement in ACs operations remains limited; farmer members do not actively participate in meetings organized by ACs boards of directors, voluntary work with ACs, voluntary work with NGOs and voluntary work with government agencies. Boards of directors elected among local farmers lead and manage ACs operations with limited human and financial resources. The current capacity and management of boards of directors remain key constraints to attracting local involvement in ACs operations. (ii) Local engagement in ACs operations is associated with access to water resources, benefits from ACs, participation in ACs activities, risk control and ACs management. Engagement in ACs operations does not significantly impact access to agricultural inputs. Farmer participation is motivated by benefits gained among the members. (iii) ACs operations have been closely supported by the MAFF and NGOs. They remain faced with various issues, such as poor management, inadequate capital accumulation, unavailable loans, loan mismanagement, limited skilled personnel, high illiteracy rates among members, small share values, a lack of access to credit facilities, access to the competitive market and a lack of support from agricultural extension services. However, farmer members are familiar with developing a business plan, but the negative impacts of climate change have caused them difficulty in managing to grow suitable crops for each season. Climate change has caused changes in water patterns, so ACs cannot adequately plan which crops should be grown in dry or wet seasons.

This study addresses a gap in the literature by exploring engagement in ACs operations, agricultural inputs, water resources, benefits from ACs operations, participation in ACs operations, risk control and management. This comprehensive study was conducted to collect empirical data and to use Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to analyze and test hypotheses regarding factors influencing local engagement in ACs operations. The results of SEM in the context of Cambodia are also applicable to developing countries because its socio-economic statuses and patterns of ACs operations are quite similar in terms of human and financial resources as well as in their supporting mechanisms. This study reveals that farmer members have access to water sources for their crops but do not receive agricultural inputs for their engagement. As a result, access to agricultural inputs is a barrier to farmer members increasing their productivity and is a challenge regarding motivating farmers to become members.