Investors’ Perceptions of Sustainability Reporting—A Review of the Experimental Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Understand what role SR credibility has in behavioral experiments;

- Synthesize credibility research on the credibility factor level, also including articles that do not focus specifically on investigating credibility factors;

- Explore the relationship between credibility factors, perceived credibility, and investment decisions;

- Identify gaps in credibility research.

- Enriches the narrow but increasing literature on SR in accounting, finance, and sustainability research in a novel way by identifying new patterns amongst the literature;

- Provides researchers with potential research gaps and suggestions for future research on SR and SR credibility;

- Highlights that all experiments—explicitly or implicitly—examine credibility, and motivates researchers to be more aware and courageous in addressing this crucial aspect in future studies on SR;

- Supports lawmakers with an overview of evidence from behavioral experiments on how individual SR attributes (which are still legislatively under development) affect investor perceptions;

- Helps companies to understand their stakeholders’ perceptions and decision-making to provide higher-quality sustainability disclosures.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Terminology

2.1.1. Sustainability Reporting

“Disclosure provided to outsiders of the organization on dimensions of performance other than the traditional assessment of financial performance from the shareholders’ and debt-holders’ viewpoints.”[16]

2.1.2. Credibility

“Disclosure credibility is defined as investors’ perceptions of the believability of a particular disclosure.”[24]

2.2. Regulatory Requirements

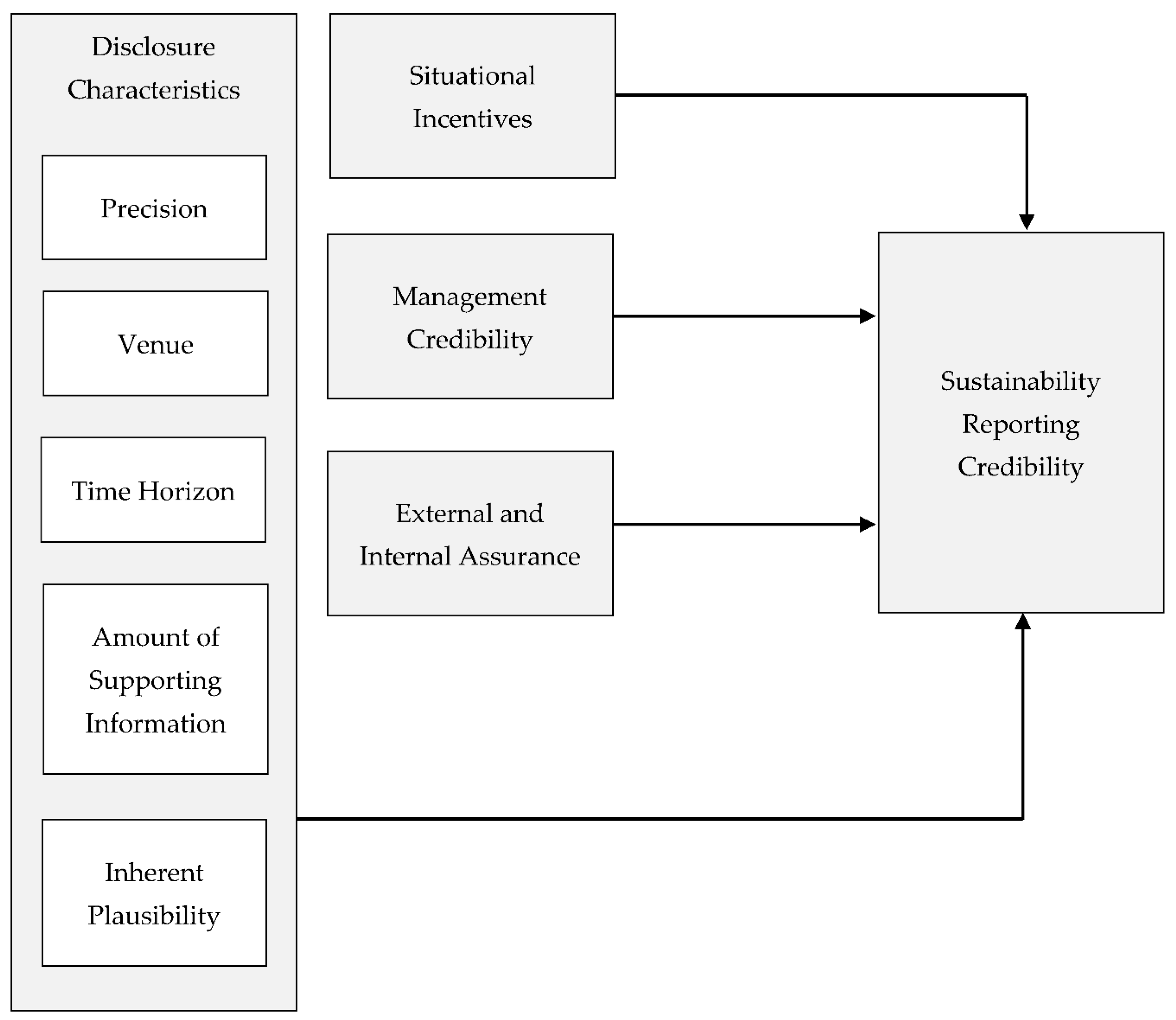

2.3. Credibility Factors

3. Materials and Methods

- Must be an original research article;

- Must employ an experimental research method;

- Must address investors’ perceptions or decision-making processes relating to SR.

4. Results

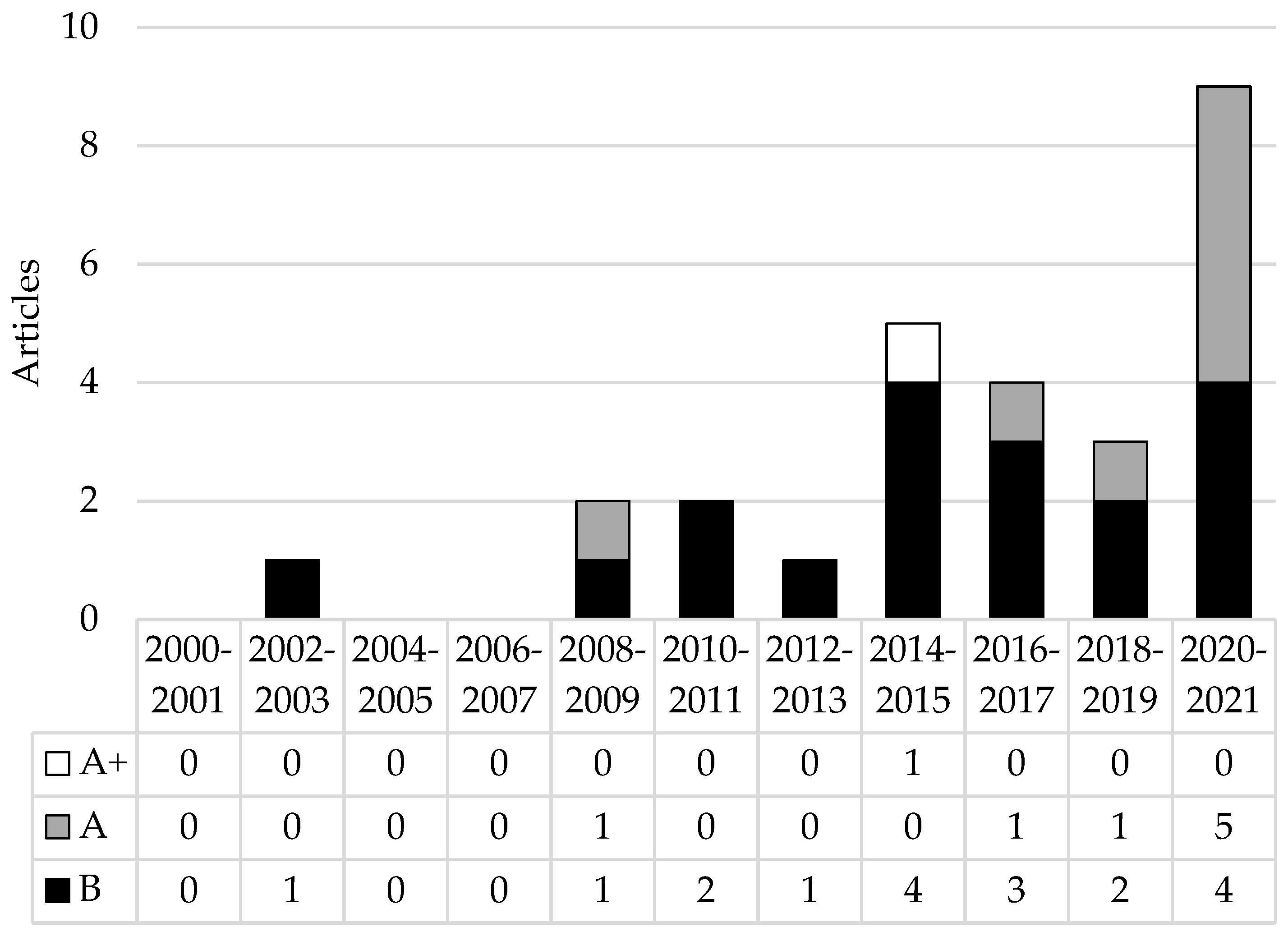

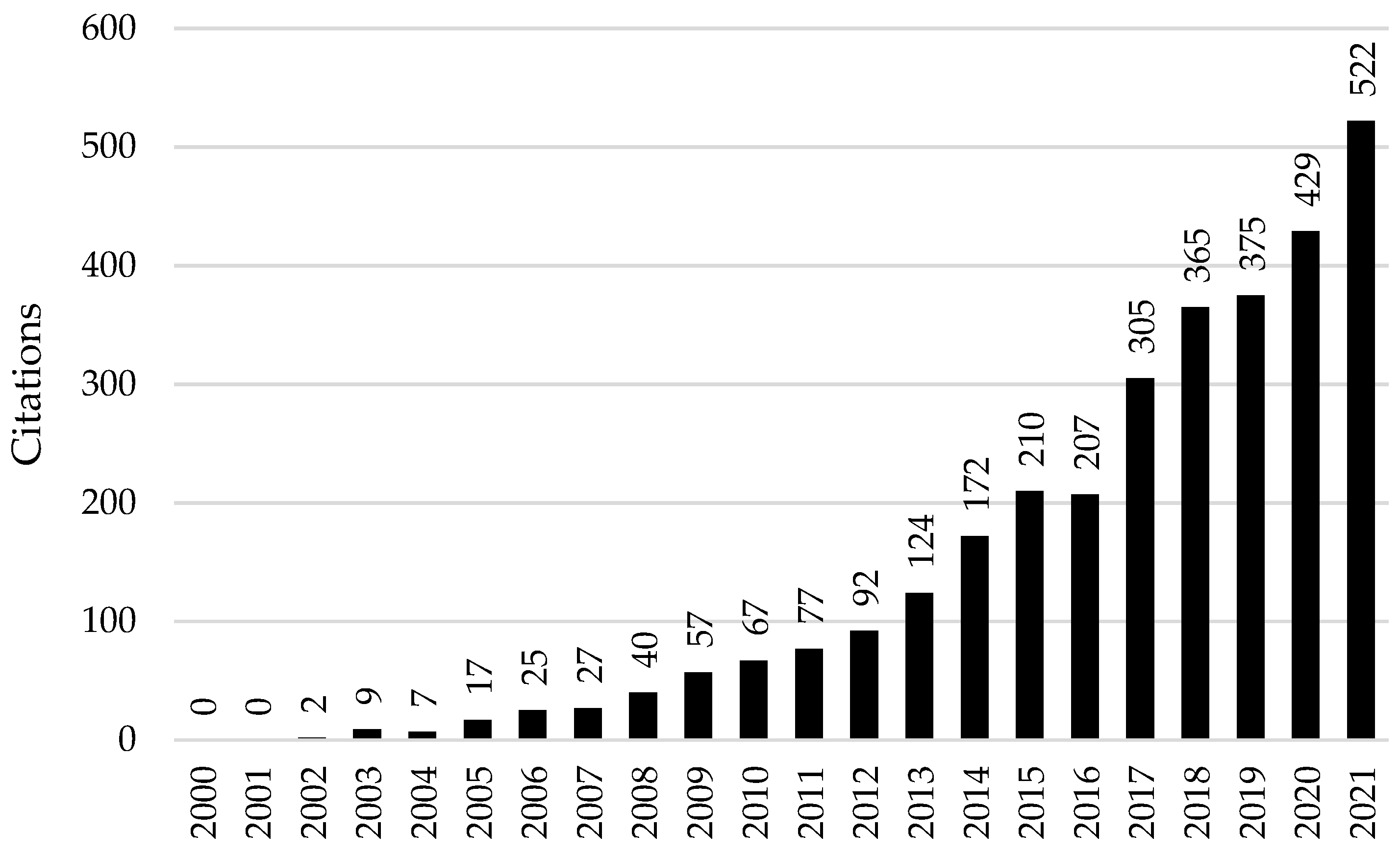

4.1. Overview

4.2. Research Topics

4.3. Theoretical Foundation

4.4. Credibility Factors

4.4.1. Situational Incentives

4.4.2. Management Credibility

4.4.3. External and Internal Assurance

4.4.4. Disclosure Characteristics

4.5. Further Characteristics

4.5.1. Investor Characteristics

4.5.2. Company Characteristics

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

“(investor) AND (perception OR decision) AND (hypothesis) AND (nonfinancial OR esg OR sustainability OR csr) AND (“financial statement”) AND (DT 2000-2021) JN (“Abacus, Accounting and Business Research “ OR “Accounting Review” OR “Accounting, Auditing, and Accountability Journal” OR “Accounting, Organizations and Society” OR “Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory” OR “Behavioral Research in Accounting” OR “Contemporary Accounting Research” OR “Critical Perspective on Accounting” OR “European Accounting Review” OR “International Journal of Auditing “ OR “Journal of Accounting and Organizational Change” OR “Journal of Accounting and Economics” OR “Journal of Accounting and Public Policy” OR “Journal of Accounting Research” OR “Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance” OR Journal of Business Ethics” OR “Journal of Business Finance and Accounting” OR “Journal of International Accounting Auditing and Taxation” OR “Review of Accounting Studies” OR “Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting”)”

Appendix B

| Author(s) (Year) [Reference] | Main Research Question | Key Results |

|---|---|---|

| Milne, M./Patten, D. (2002) [50] | What role do environmental disclosures play in producing a legitimating effect on investors? | Positive disclosures can restore or repair an organization’s legitimacy. |

| Berens, G. et al. (2007) [59] | Can Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Corporate Ability (CA) Compensate Each Other? | For stock preferences, a poor CA can be compensated by a good CSR, and vice versa. |

| Holm, C./Rikhardsson, P. (2008) [51] | How do environmental information, investment horizon, and experience of investors influence investors’ investment allocation decisions? | Environmental information disclosure influences investment allocation decisions, whereby investment horizon and experience level of investors mitigate this effect. |

| Coram, P. J. et al. (2009) [32] | How does non-financial performance and assurance influence investors’ stock price estimates? | Non-financial performance has a significant effect on stock price estimates. The assurance of a report only has a significant effect when the non-financial performance indicators are positive. |

| van der Laan Smith, J. et al. (2010) [54] | How does culture and stakeholder belief influence investors’ investment decision? | Corporate social disclosure impacts investment behavior in all countries, but the stakeholder orientation influences the extent. |

| Pflugrath, G. et al. (2011) [58] | How do investors’ nationality, firms’ industry, and the type of assurance provider influence investors’ perceived credibility? | The effect of assurance on perceived credibility is more significant for a company in the mining industry than the retail industry. Assurance is valued across countries, but there exist differences in detail. |

| Green, W./Li, Q. (2012) [69] | Does an expectation gap in the assurance of greenhouse gas emissions for different industries exist between different stakeholders? | Expectation gap in the emission assurance setting exists. Differences exist concerning the responsibilities of the assurer and management and the reliability and decision usefulness. |

| Elliott, W. B. et al. (2014) [45] | How do an explicit assessment and CSR performance influence investors’ estimated firm value? | Investors unintentionally use their affective reactions to CSR performance to derive estimates of fundamental value, with an explicit assessment of CSR performance significantly diminishing this unintended effect. |

| Wang, L./Tuttle, B. (2014) [33] | How does assured CSR disclosure and management turnover influence investors’ financial disclosure credibility? | Overall impressions about management’s honesty, credibility, and trustworthiness influence investors’ assessments of financial disclosure credibility and the willing to pay for a company’s stock. |

| Brown-Liburd, H./Zamora, V. (2015) [30] | How do the CSR investment level, assurance, and pay-for-CSR performance influence the investors’ investment decisions? | In the presence of pay-for-CSR performance and a high CSR investment level, investors’ stock price assessments are more significant only when CSR assurance is also present. |

| Cheng, M. et al. (2015) [35] | How does the strategic relevance of ESG indicators and assurance influence investors’ investment decisions? | Assurance increases investors’ willingness to invest to a greater extent when ESG indicators have high relevance to the company strategy. |

| Zahller, K. A. et al. (2015) [52] | How do exogenous shocks and CSR disclosure quality influence investors’ investment decisions? | When CSR disclosures are higher quality, investors perceive organizational legitimacy to be higher. Higher levels of perceived organizational legitimacy are associated with greater organizational resilience to an intra-industry exogenous shock. |

| Cohen, J. et al. (2017) [36] | How does the value relevance of CSR disclosures and the corporate governance quality influence the investors’ investment decision? | Non-professional investors are more (less) likely to invest in firms having stronger (weaker) CSR performance. Non-professional investors are more (less) likely to invest in firms having a strong (weak) corporate governance structure. |

| Dong, L. (2017) [62] | Do non-professional investors rely on non-financial information? | Non-financial information affects high-experience investors more than low-experience investors. Non-financial information affects long-term investors more than low-experience short-term investors. |

| Elliott, W. B. et al. (2017) [46] | How do presentation style, strategy frame, and numeracy influence investor judgments? | A fit between the strategy frame and the presentation style of a firm’s CSR report causes less numerate investors to be more willing to invest than when a fit is not present. |

| Shen, H. et al. (2017) [37] | How do CSR performance and assurance influence non-professional investors’ investment decisions? | Credibility partially mediates the relationship between assurance and investment decisions. The effect is more significant when CSR disclosures are positive than negative. |

| Brown-Liburd, H. et al. (2018) [34] | Do investors use CSR disclosure items as a fairness heuristic in their investment decision? | Fairness perceptions are higher when CSR investment is above (versus below) the industry average, and fairness perceptions partially mediate the impact of the CSR investment level on investment amount allocations. |

| Reimsbach, D. et al. (2018) [57] | How do the integration and the assurance of sustainability and financial information influence the investors’ investment-related judgments? | Assurance leads to higher investment-related judgments. Assurance effect was weaker in the case of integrated reporting compared to separate reporting. |

| Bucaro, A. et al. (2020) [60] | How do the report type (separate report vs. single report) and firm’s CSR performance influence the investors’ investment decision? | Integrating CSR measures reduces the extent to which investors include CSR measures in their judgments. The report-type effect is more attributable to very positive CSR performance than positive CSR performance. |

| Guiral, A. et al. (2020) [47] | How do the materiality and valence influence the Korean investors’ fundamental value estimates? | Investors likely use a heuristic approach to process immaterial and positive CSR issues, and a more deliberate and systematic approach to process material or negative CSR issues. |

| Sheldon, M./Jenkins, J. (2020) [25] | How do firms’ relative performance and level of assurance influence the investors’ perceived believability of an environmental report? | Negative performance reports are more believable than positive performance reports. The firm performance effect is eliminated in the presence of limited or reasonable assurance. |

| Austin, C. R. et al. (2021) [48] | How does a company’s gender pay information affect investors’ willingness to invest in the company? | Gender pay disclosure affects perceptions of fairness (economic consequences) directly (indirectly through fairness). |

| Baier, C. et al. (2021) [42] | How does the selection of assurance topics and the format influence the assurance signal and credibility perception? | Reference explicitness and assurance depth influence the assurance signal and the perceived credibility of a sustainability report. |

| De Villiers, C. et al. (2021) [56] | Are shareholders willing to pay for financial, social, and environmental disclosure? | Are willing to pay for financial disclosure and environmental disclosure but value changes in financial disclosure more than in social or environmental disclosure. |

| Hoang, H./Phang, S. (2021) [40] | How do combined assurance and reported reliability risks influence the investors’ perceived reliability and willingness to invest? | Combined assurance restores investors’ perceived reliability and willingness to invest to a greater extent when there are high-reliability risks. |

| Hoang, H./Trotman, K. (2021) [39] | How do the assurance type and explicit assessment influence the investors’ fundamental value estimates? | In the context of no prompt to explicitly assess performance, the investors who receive an assurance report at a reasonable level derive the highest fundamental value estimates. |

| Stuart, A. C. et al. (2021) [38] | How does management’s stated purpose for undertaking CSR, assurance, and the presence of a company-specific negative event influence investor’s company evaluation? | Lacking a negative event, investment judgments are stronger when CSR activities are intended to achieve financial results. Assurance complements disclosure of CSR activities by contributing to protection against the impact of negative events. |

References

- Ballou, B.; Casey, R.J.; Grenier, J.H.; Heitger, D.L. Exploring the Strategic Integration of Sustainability Initiatives: Opportunities for Accounting Research. Account. Horiz. 2012, 26, 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amel-Zadeh, A.; Serafeim, G. Why and How Investors Use ESG Information: Evidence from a Global Survey. Financ. Anal. J. 2018, 74, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. Corporate social responsibility and access to finance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, A.-A.; Chen, L.-N.; Hu, J.-C. A Study of the Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility Report and the Stock Market. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, D.S.; Li, O.Z.; Tsang, A.; Yang, Y.G. Voluntary Nonfinancial Disclosure and the Cost of Equity Capital: The Initiation of Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting. Account. Rev. 2011, 86, 59–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Maxwell, J.W. Greenwash: Corporate Environmental Disclosure under Threat of Audit. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2011, 20, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsdottir, B.; Sigurjonsson, T.O.; Johannsdottir, L.; Wendt, S. Barriers to Using ESG Data for Investment Decisions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoni, A.; Kiseleva, E.; Terzani, S. Evaluating the Intra-Industry Comparability of Sustainability Reports: The Case of the Oil and Gas Industry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolowy, H.; Paugam, L. The expansion of non-financial reporting: An exploratory study. Account. Bus. Res. 2018, 48, 525–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastini, K.; Getzin, F.; Lachmann, M. The effects of strategic choices and sustainability control systems in the emergence of organizational capabilities for sustainability. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2022, 35, 1121–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swieringa, R.J.; Weick, K.E. An Assessment of Laboratory Experiments in Accounting. J. Account. Res. 1982, 20, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, R.; Bloomfield, R.; Nelson, M.W. Experimental research in financial accounting. Account. Organ. Soc. 2002, 27, 775–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotman, K.T.; Tan, H.C.; Ang, N. Fifty-year overview of judgment and decision-making research in accounting. Account. Financ. 2011, 51, 278–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomfield, R.; Nelson, M.W.; SOLTES, E. Gathering Data for Archival, Field, Survey, and Experimental Accounting Research. J. Account. Res. 2016, 54, 341–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haji, A.A.; Coram, P.; Troshani, I. Consequences of CSR reporting regulations worldwide: A review and research agenda. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkens, M.; Paugam, L.; Stolowy, H. Non-financial information: State of the art and research perspectives based on a bibliometric study. Comptab. Contrôle Audit 2015, 21, 15–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. Psychological Study of Human Judgment: Implications for Investment Decision Making. J. Financ. 1972, 27, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M. Value-Enhancing Capabilities of CSR: A Brief Review of Contemporary Literature. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gödker, K.; Mertins, L. CSR Disclosure and Investor Behavior: A Proposed Framework and Research Agenda. Behav. Res. Account. 2018, 30, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R. Examination and implications of experimental research on investor perceptions. J. Account. Lit. 2019, 43, 145–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosi, M.K.; Lajuni, N.; Wellfren, A.C.; Lim, T.S. Sustainability Reporting through Environmental, Social, and Governance: A Bibliometric Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, H.B.; Hail, L.; Leuz, C. Mandatory CSR and sustainability reporting: Economic analysis and literature review. Rev. Account. Stud. 2021, 26, 1176–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Shailer, G. Stakeholders’ perceptions of factors affecting the credibility of sustainability reports. Br. Account. Rev. 2022, 54, 101002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, M. How Do Investors Assess the Credibility of Management Disclosures? Account. Horiz. 2004, 18, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, M.D.; Jenkins, J.G. The influence of firm performance and (level of) assurance on the believability of management’s environmental report. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2020, 33, 501–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 32014L0095–EN; Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 Amending Directive 2013/34/EU as Regards Disclosure of Non-Financial and Diversity Information by Certain Large Undertakings and Groups. European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2014.

- A9-0059/2022; Proposal for a DIRECTIVE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL Amending Directive 2013/34/EU, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, as Regards Corporate Sustainability Reporting. European Parliament: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2021.

- Securities and Exchange Commission. SEC Proposes Rules to Enhance and Standardize Climate-Related Disclosures for Investors. 2022. Available online: https://www.sec.gov/rules/proposed/2022/33-11042.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Aerts, W.; Cormier, D. Media legitimacy and corporate environmental communication. Account. Organ. Soc. 2009, 34, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown-Liburd, H.; Zamora, V.L. The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Assurance in Investors’ Judgments When Managerial Pay is Explicitly Tied to CSR Performance. AUDITING A J. Pract. Theory 2015, 34, 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirst, D.E.; Koonce, L.; Miller, J. The Joint Effect of Management’s Prior Forecast Accuracy and the Form of Its Financial Forecasts on Investor Judgment. J. Account. Res. 1999, 37, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coram, P.J.; Monroe, G.S.; Woodliff, D.R. The Value of Assurance on Voluntary Nonfinancial Disclosure: An Experimental Evaluation. AUDITING A J. Pract. Theory 2009, 28, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Tuttle, B. Using corporate social responsibility performance to evaluate financial disclosure credibility. Account. Bus. Res. 2014, 44, 523–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown-Liburd, H.; Cohen, J.; Zamora, V.L. CSR Disclosure Items Used as Fairness Heuristics in the Investment Decision. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 152, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.M.; Green, W.J.; Ko, J.C.W. The Impact of Strategic Relevance and Assurance of Sustainability Indicators on Investors’ Decisions. AUDITING A J. Pract. Theory 2015, 34, 131–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Holder-Webb, L.; Khalil, S. A Further Examination of the Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility and Governance on Investment Decisions. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 146, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Wu, H.; Chand, P. The impact of corporate social responsibility assurance on investor decisions: Chinese evidence. Int. J. Audit. 2017, 21, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, A.C.; Bedard, J.C.; Clark, C.E. Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosures and Investor Judgments in Difficult Times: The Role of Ethical Culture and Assurance. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 171, 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, H.; Trotman, K.T. The Effect of CSR Assurance and Explicit Assessment on Investor Valuation Judgments. AUDITING A J. Pract. Theory 2021, 40, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, H.; Phang, S.-Y. How Does Combined Assurance Affect the Reliability of Integrated Reports and Investors’ Judgments? Eur. Account. Rev. 2021, 30, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. Job market signaling. Uncertainty in Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1978; pp. 281–306. ISBN 9780122148507. [Google Scholar]

- Baier, C.; Göttsche, M.; Hellmann, A.; Schiemann, F. Too Good To Be True: Influencing Credibility Perceptions with Signaling Reference Explicitness and Assurance Depth. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 178, 695–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N.; Clore, G.L. Mood, misattribution, and judgments of well-being: Informative and directive functions of affective states. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 45, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N.; Clore, G.L. Mood as Information: 20 Years Later. Psychol. Inq. 2003, 14, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, W.B.; Jackson, K.E.; Peecher, M.E.; White, B.J. The Unintended Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility Performance on Investors’ Estimates of Fundamental Value. Account. Rev. 2014, 89, 275–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, W.B.; Grant, S.M.; Rennekamp, K.M. How Disclosure Features of Corporate Social Responsibility Reports Interact with Investor Numeracy to Influence Investor Judgments. Contemp. Account. Res. 2017, 34, 1596–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiral, A.; Moon, D.; Tan, H.-T.; Yu, Y. What Drives Investor Response to CSR Performance Reports? Contemp. Account. Res. 2020, 37, 101–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, C.R.; Bobek, D.D.; Harris, L.L. Does information about gender pay matter to investors? An experimental investigation. Account. Organ. Soc. 2021, 90, 101193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patten, D.M. Intra-industry environmental disclosures in response to the Alaskan oil spill: A note on legitimacy theory. Account. Organ. Soc. 1992, 17, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, M.J.; Patten, D.M. Securing organizational legitimacy. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2002, 15, 372–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, C.; Rikhardsson, P. Experienced and Novice Investors: Does Environmental Information Influence Investment Allocation Decisions? Eur. Account. Rev. 2008, 17, 537–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahller, K.A.; Arnold, V.; Roberts, R.W. Using CSR Disclosure Quality to Develop Social Resilience to Exogenous Shocks: A Test of Investor Perceptions. Behav. Res. Account. 2015, 27, 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984; ISBN 0-273-01913-9. [Google Scholar]

- van der Laan Smith, J.; Adhikari, A.; Tondkar, R.H.; Andrews, R.L. The impact of corporate social disclosure on investment behavior: A cross-national study. J. Account. Public Policy 2010, 29, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, P.M.; Palepu, K.G. Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature. J. Account. Econ. 2001, 31, 405–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Villiers, C.; Cho, C.H.; Turner, M.J.; Scarpa, R. Are Shareholders Willing to Pay for Financial, Social and Environmental Disclosure? A Choice-based Experiment. Eur. Account. Rev. 2021, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimsbach, D.; Hahn, R.; Gürtürk, A. Integrated Reporting and Assurance of Sustainability Information: An Experimental Study on Professional Investors’ Information Processing. Eur. Account. Rev. 2018, 27, 559–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflugrath, G.; Roebuck, P.; Simnett, R. Impact of Assurance and Assurer’s Professional Affiliation on Financial Analysts’ Assessment of Credibility of Corporate Social Responsibility Information. AUDITING A J. Pract. Theory 2011, 30, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berens, G.; van Riel, C.B.M.; van Rekom, J. The CSR-Quality Trade-Off: When can Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Ability Compensate Each Other? J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 74, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucaro, A.C.; Jackson, K.E.; Lill, J.B. The Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility Measures on Investors’ Judgments when Integrated in a Financial Report versus Presented in a Separate Report. Contemp. Account. Res. 2020, 37, 665–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachmann, M.; Stefani, U.; Wöhrmann, A. How Do Professional Debt and Equity Providers Read Income Statements? Evidence from an Eye-Tracking Study. 2022. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4200409 (accessed on 28 October 2022).

- Dong, L. Understanding investors’ reliance on disclosures of nonfinancial information and mitigating mechanisms for underreliance. Account. Bus. Res. 2017, 47, 431–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, J.J.; Tewari, M. Firm Characteristics, Industry Context, and Investor Reactions to Environmental CSR: A Stakeholder Theory Approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 833–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, F.D.; Hopkins, P.E.; Wood, D.A. The Effects of Financial Statement Information Proximity and Feedback on Cash Flow Forecasts*. Contemp. Account. Res. 2010, 27, 101–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickens, C.D.; Carswell, C.M. The Proximity Compatibility Principle: Its Psychological Foundation and Relevance to Display Design. Hum. Factors 1995, 37, 473–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachur, T.; Bröder, A.; Marewski, J.N. The recognition heuristic in memory-based inference: Is recognition a non-compensatory cue? J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 2008, 21, 183–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, D.G.; Gigerenzer, G. Models of ecological rationality: The recognition heuristic. Psychol. Rev. 2002, 109, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rennekamp, K.M. Processing Fluency and Investors’ Reactions to Disclosure Readability. J. Account. Res. 2012, 50, 1319–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, W.; Li, Q. Evidence of an expectation gap for greenhouse gas emissions assurance. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2011, 25, 146–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Description | Number |

|---|---|

| Articles identified with the search string | 1045 |

| Excluded after initial inclusion check | (−) 988 |

| Potentially relevant articles after initial inclusion check | 57 |

| Excluded after final inclusion check | (−) 44 |

| Articles included after final inclusion check | 13 |

| Additional relevant articles identified in the reverse research | (+) 14 |

| Total number of articles included in this review | 27 |

| Name | Description | Author(s) (Year) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attribution Theory | Individuals evaluate the incentives of information sources to determine the message’s credibility. Individuals tend to assume that messages inconsistent with the source’s incentives are more credible than consistent messages [24]. | Coram, P. J. et al. (2009) | [32] |

| Wang, L./Tuttle, B. (2014) | [33] | ||

| Brown-Liburd, H./Zamora, V. (2015) | [34] | ||

| Cheng, M. et al. (2015) | [35] | ||

| Cohen, J. et al. (2017) | [36] | ||

| Shen, H. et al. (2017) | [37] | ||

| Stuart, A. et al. (2019) | [38] | ||

| Sheldon, M./Jenkins, J. (2020) | [25] | ||

| Hoang, H./Trotman, K. (2021) | [39] | ||

| Hoang, H./Phang, S. (2021) | [40] | ||

| Signaling Theory | The sender chooses whether and how to communicate (signal) the disclosures. The receiver must choose how to interpret the signal [41]. | Cheng, M. et al. (2015) | [35] |

| Baier, C. et al. (2021) | [42] | ||

| Affect-as- Information Theory | Individuals attend to the affect or feelings they are experiencing as a source of information to inform their judgment and, unintentionally, their subsequent decisions [43,44]. | Elliott, W. B. et al. (2014) | [45] |

| Elliott, W. B. et al. (2017) | [46] | ||

| Guiral, A. et al. (2020) | [47] | ||

| Austin, C. et al. (2020) | [48] | ||

| Hoang, H./Trotman, K. (2021) | [39] |

| Name | Description | Author(s) (Year) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legitimacy Theory | Companies use SR to legitimize certain actions, change stakeholder perceptions or prevent negative stakeholder reactions [49]. | Milne, M./Patten, D. (2002) | [50] |

| Holm, C./Rikhardsson, P. (2008) | [51] | ||

| Zahller, K. A. et al. (2015) | [52] | ||

| Stuart, A. et al. (2019) | [38] | ||

| Stakeholder Theory | Companies use SR to manage and affect relationships with important stakeholder groups, such as investors [53]. | Holm, C./Rikhardsson, P. (2008) | [51] |

| van der Laan Smith, J. et al. (2010) | [54] | ||

| Zahller, K. A. et al. (2015) | [52] | ||

| Agency Theory | Companies provide SR to reduce uncertainty among stakeholders because of information asymmetry, and stakeholders ask for sustainability information to pursue personal goals, such as ethical investing [55]. | Holm, C./Rikhardsson, P. (2008) | [51] |

| Zahller, K. A. et al. (2015) | [52] | ||

| Stuart, A. et al. (2019) | [38] | ||

| Austin, C. et al. (2020) | [48] | ||

| De Villiers, C. et al. (2021) | [56] |

| Field | Operationalization | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Situational Incentives | Sustainability Reporting Performance | Positive performance lowers credibility. It also extends the positive effect of other credibility factors. |

| Firms’ Industry Type | Industries with more incentives to report positive disclosures have lower credibility. This also extends the positive effects of other credibility factors. | |

| Management Credibility | Corporate Governance | Inconsistent findings. Corporate governance has a significant versus marginal effect on investment decisions. |

| Press Release | A negative press release lowers both credibility and willingness to invest. | |

| External and Internal Assurance | External Assurance (Presence) | External assurance positively affects credibility and raises stock price estimates. Positive effects only appear when situational incentives are present. |

| External Assurance (Level) | Inconsistent findings. Both limited and reasonable assurance increase credibility versus limited assurance, but the lack of reasonable assurance increases credibility. Reasonable assurance has the strongest positive effect on value estimates. | |

| External Assurance (Provider) | Inconsistent findings. Assurance provider has no impact on decision-making, versus assurance provider has an impact that depends on the specific context. | |

| Internal Assurance | Combined assurance positively influences investors’ perception of credibility and willingness to invest. | |

| Disclosure Characteristics | Precision | Participants perceive a high level of precision positively. |

| Venue | Inconsistent findings. Sustainability disclosures have a more significant impact on investors‘ judgments when it appears in a separate versus integrated report. | |

| Time Horizon | No results. | |

| Supporting Information | Supporting information only has a positive impact on stock price assessment when it is combined with independent assurance. Shareholders are willing to pay for financial and environmental disclosures. They do not find evidence that shareholders are willing to pay for social disclosures. | |

| Inherent Plausibility | No results. | |

| Investor Characteristics | Profession and Experience | The main effect of positive sustainability disclosures applies to all investors. However, it affects high-experience investors to a stronger degree. |

| Nationality | Investors with different nationalities react differently to sustainability disclosures and differ in assurance provider preferences. | |

| Investment Horizon | Sustainability reporting increases investment interest for the long-term, but not for short-term investment horizons. | |

| Numeracy | While less numerate investors are affected by a fit between a firm‘s strategy frame and presentation style, more numerate investors are not affected. | |

| Company Characteristics | Industry | See above (situational incentives) |

| Reporting performance | See above (situational incentives) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Misiuda, M.; Lachmann, M. Investors’ Perceptions of Sustainability Reporting—A Review of the Experimental Literature. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16746. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416746

Misiuda M, Lachmann M. Investors’ Perceptions of Sustainability Reporting—A Review of the Experimental Literature. Sustainability. 2022; 14(24):16746. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416746

Chicago/Turabian StyleMisiuda, Maria, and Maik Lachmann. 2022. "Investors’ Perceptions of Sustainability Reporting—A Review of the Experimental Literature" Sustainability 14, no. 24: 16746. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416746

APA StyleMisiuda, M., & Lachmann, M. (2022). Investors’ Perceptions of Sustainability Reporting—A Review of the Experimental Literature. Sustainability, 14(24), 16746. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416746