1. Introduction

The number of people who travel daily represents one of the main current sustainability issues [

1]. Although sustainability concepts have emerged, such as the ‘responsible traveller’, who, driven by personal and community interests and values, consciously chooses more sustainable mobility alternatives [

2], and although emissions have decreased, sustainability efforts are insufficient [

1].

Compounding this latent need, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has generated setbacks with respect to the increase in the use of private cars [

3], in part due to restrictions in the transport sector, changing mobility habits and accelerating, in turn, the importance of more flexible transport systems [

4]. This has forced researchers and decision makers to reconsider the relationships between mobility, urban space and other aspects, such as health, to ensure physical distancing and the needs of inhabitants [

5].

Thus, it is essential to identify the most effective strategies and to design solutions that promote sustainable mobility [

6] in such a way as to avoid the use of private cars but not overload public transport [

7]. The identification and development of sustainable mobility strategies have expanded significantly in recent years [

4] and have focused mainly on recognising the fundamental role of the bicycle as a means of sustainable transport [

8].

The strategies that prioritise the use of bicycles have focused more on shared bicycle systems because of multiple benefits, such as reductions in congestion and pollution [

9], allowing users to obtain a bicycle at a station located in the city and to return the bicycle to any other station [

10].

The general mobility trend in Latin America is not sustainable [

11]. However, there are some shared bicycle systems, such as the “EnCicla” programme in the city of Medellín-Colombia; apart from its impact on sustainability, EnCicla has increased well-being, health, quality of life, job opportunities [

12], and aspects related to happiness in communities [

13]. Despite these positive factors, public space limitations, health problems associated with air quality [

14], traffic accidents involving bicycles [

15] and increases in the number of bicycle thefts [

16] have also been observed.

Due to incidences, both negative and positive, related to shared bicycle systems, the research community has increased interest in the topic, particularly understanding the experiences and behaviours of users [

17].

This study highlights the importance of the participation of the public as stakeholders who have and need knowledge for planning and decision making to address issues in a manner that is sustainable, economically viable, technically feasible, environmentally compatible and publicly acceptable [

18], and to implement patterns that strengthen the most sustainable habits in terms of mobility [

19].

Keeping in mind the growing importance of incorporating sustainability in urban transport [

20] and that the city of Medellín, Colombia, has undergone significant urban growth that has prioritised the construction of a new means of transport as a definitive agent in the sustainable regeneration of the city [

21], there is a need to identify the main problems in adopting sustainable measures [

22]. These must consider interoperability, mobility, quality of life and sustainability as four of the six key elements in the study of methodological models that evaluate sustainability in the city of Medellín as a smart city [

23].

Therefore, the objective of this study was to identify the main behavioural factors among users of the public bicycle programme EnCicla in the city of Medellín, Colombia, so that, based on the findings, the growing discussion about the adoption of sustainable transport alternatives can be expanded in the context of emerging countries through behavioural theories, such as the Theory of Planned Behaviour, validated in the scientific literature.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Behavioural Factors

Behavioural factors are elements that have the potential to affect the behaviour of a person in the performance of an activity, considering that the will itself is as important as the activity to be performed. An understanding of behavioural factors can facilitate modelling [

24], which is usually used to analyse both operational decisions in companies and the acceptance or adoption of sustainable mobility options [

25].

Many psychological factors affect the attitude of consumers towards sustainable mobility alternatives; examples of such factors include environmental concerns and consumer innovation [

26]. Dynamic leadership, mutual respect, rationality and even social influence have been disrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic, and this disruption is associated with some behavioural factors, for example, bad mood, irritability, anger, poor sleep quality, and emotional disorders (such as anxiety and depression) [

27], which directly affect the adoption and use of sustainable transport solutions and services based on information and communication technologies (ICTs).

2.2. Model

The best way to describe human social behaviour is through formulated models [

28]. Therefore, to understand the behavioural factors of users of the EnCicla programme in Medellín, there is a series of models validated by the scientific literature; these models include the Random Utility Theory, the Perspectives Theory, and the Theory of Reasoned Action. However, of the theories in question, the one most used in the academic field is the Theory of Reasoned Action, which was replaced by the Theory of Planned Behaviour [

29]. This theory establishing itself as a theory that, based on the evaluation of variables such as attitude, subjective norms and behaviour control, allows us to know social behaviour in a specific way [

30]. It facilitates, on the one hand, the Theory of Planned Behaviour and helps clarify the factors that influence this evaluated behaviour, which in this case is the use of bicycles as an alternative means of transport by inhabitants of the city of Medellín. On the other hand, because it conceives of human beings as having sensible and predictable behaviour, this theory allows us to predict the evaluated behaviour for decision making [

31,

32].

However, it is known that the applications of the Theory of Planned Behaviour have been diverse, leading to extensions of it, through which new latent variables have been added for understanding and predicting social behaviour. However, no studies have used the theory to understand the use of bicycles as an alternative means of transport in the context of emerging economies, which account for social, cultural, environmental and economic characteristics similar to the city of Medellín, Colombia; therefore, this study makes use of the original theory.

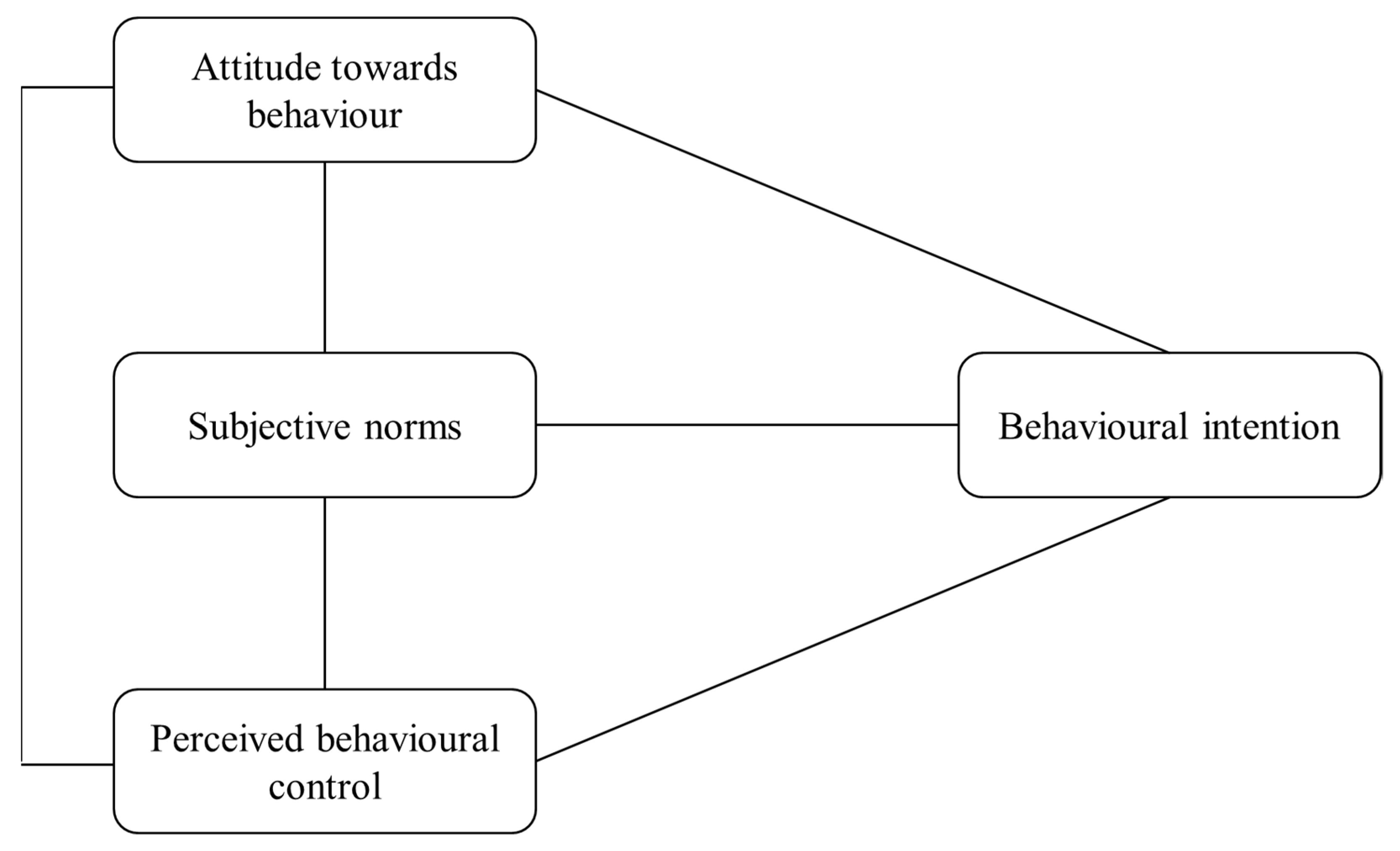

Figure 1 shows the model on which the research was based:

2.3. Theory of Planned Behaviour and Behavioural Factors

The Theory of Planned Behaviour is widely used for understanding behavioural and sociobehavioural factors in multiple contexts; for example, theory is used to understand behavioural factors that indicate purchase intention [

34], that indicate an intention to send text messages [

35], and that determine traffic offence behaviours [

36].

In general, subjective norms, attitude towards behaviour and perceived behavioural control are used to measure intention [

37]. Specifically, attitude towards behaviour is the extent to which a person has a favourable or unfavourable assessment of a certain behaviour [

38]. Perceived behavioural control refers to the degree to which people consider a behaviour to be under their voluntary control [

39].

Some authors have identified the effects of attitude towards behaviour on perceived behavioural control [

40], and an understanding of this relationship has served as a basis for designing programmes that promote behavioural changes, as shown in [

41].

H1: Attitude towards behaviour (ATT) has a significant positive effect on perceived behaviour control (PC).

The Theory of Planned Behaviour, as a construct that explains intentions, relates subjective norms, attitudes towards behaviour and perceived behavioural control [

42]. Given that attitude towards behaviour and perceived behavioural control are defined as social pressures to perform or not perform a certain behaviour, normative beliefs and motivations [

38], forming codes of conduct regarding standards, expectations and norms [

43] that can be explained, in turn, by the construct of attitude towards behaviour in an interaction, must be understood to analyse their influence on intention.

H2: ATT has a significant positive effect on subjective norms (SNs).

Because the concepts of SNs and PC were previously defined, it is evident that the literature refers to an interaction between SNs and all the other variables of the Theory of Planned Behaviour [

44], with the construct of SNs moderating the other variables [

45].

Among those other variables that have an incidence or that can be predicted from SNs, there is the latent variable of PC, forming one of the main control interactions originally described by [

44], and by means of which the behaviour is precisely analysed.

H3: SNs have a significant positive effect on PC.

The Theory of Planned Behaviour [

28] indicates that the understanding of the automation of certain human actions allows determining the factors that affect the intention towards a certain behaviour. This has been complemented by the use of other constructs (ATT, SNs and PC) to explain behaviours and behavioural intention [

30].

After identifying the structure of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to explain the intention towards a behaviour, the authors [

46] add that this correlation is explained by positive impacts on the intention of the individuals analysed, as identified by [

47], when mentioning the significant positive effects of attitude, control and SNs on the intention to use sustainable media. Therefore, the variables ATT [

48], SNs [

45] and PC [

44] individually explain the intention towards a behaviour.

H4: ATT has a significant positive effect on behavioural intention (BI).

H5: SNs have a significant positive effect on BI.

H6: PC has a significant positive effect on BI.

Finally, with all the relationships and interactions that gave rise to the hypotheses defined,

Figure 2 graphically represents the position of each hypothetical statement, which will be confirmed or refuted by means of statistical treatment.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design and Approach

This study was designed to identify the main behavioural factors among users of the EnCicla public bicycle system in the city of Medellín. A quantitative approach was employed; compared to qualitative approaches, this approach allows a larger sample and requires less time to collect information [

49].

A quantitative approach was adopted to understand the importance of measurement in social research contexts and the need for reliable and valid instruments [

50]. In this investigation, questionnaires were validated, a statistical analysis was developed based on previously proposed constructs, and a relationship between them was established.

Likewise, the research was exploratory in scope, understood as a first tentative analysis of a new topic, the proposal of new ideas, or new hypotheses for an old topic [

51]. In the context of Medellín, no studies on the EnCicla system have been conducted from the perspective of the Theory of Planned Behaviour.

3.2. Instrument

To fulfil the objective proposed in the research, a self-administered questionnaire was designed that consisted of a form to record responses to questions without intervention from the interviewer [

52]. This survey consisted of four questions per construct, resulting in a total of 16 questions. The instrument is provided in

Table 1.

3.3. Sample

The self-administered questionnaire was taken by 210 people through convenience sampling, an approach that, according to [

53], is relevant for exploratory studies to understand the situational reality of an object of study and the amount of information collected for data analysis. As this study is an exploratory study, the sample size is assumed to be appropriate. To reduce the possible apprehension bias that may be generated by the size of the sample, the questionnaire kept the participants completely anonymous, and they were told that there were no correct or incorrect answers and that the questions should be answered with all possible sincerity. It is important that the results are carefully examined for contexts similar to the one used in this research.

The self-administered instrument was applied directly in the areas defined by the local authorities for the use of the bicycles of the EnCicla program. The instruments were delivered directly to users to ensure that those who responded were regular users of the system. Given the form of application of the instruments, it was guaranteed that the participants reflected the characteristics of the urban population that usually uses the EnCicla service.

This, in turn, is relevant for the application of the instrument among people who have greater access and are closer in proximity, without restricting the maximum number of respondents; a larger sample size favours the use of constructs measured reflectively [

54].

Specifically, the representative sample of the population was 53.33% men and 46.67% women; considering the diversity of users of the EnCicla public bicycle programme, the participants were not differentiated by specific age ranges or by profession categorisations.

3.4. Data Processing and Analysis

The data processing and analysis for this research was performed using the statistical software Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) (IBM) [

55] because of its strength in processing quantitative research data in the social field [

56] and its significance analysis [

57].

SPSS is also a comparably easy-to-use software with commonly used procedures, especially in the academic world [

55], and is therefore considered suitable for analysing data derived from instruments. As a confirmatory factor analysis, according to [

52], it is essential to begin with the validity analysis of each construct to subsequently analyse its reliability.

4. Results

The surveys applied allowed the identification of some descriptive elements of the behaviour of the users in relation to the frequency of use of the public bicycle programme, the reasons for doing so, safety aspects associated with bicycle use, and some perceived personal experiences. In that sense, of the total number of people surveyed, 16.67% use the public bicycle system daily, 14.29% use it once a week, 14.76% use it twice a week, 21.43% use it three times a week, and 32.86% use it with an unspecified frequency.

Notably, 55.24% of users prioritised the use of the public bicycle system to save time, 38.10% use the system to save money, 36.19% use the system because of environmental objectives, 35.71% use the system for purely recreational purposes, and 9.05% use the system solely because of its ease of use; 20.48% reported that when using the system, they had travel objectives, to the university, to work, or to any unspecified place. Importantly, the respondents could select more than one option for this item.

Regarding the relationship between safety aspects and behavioural factors, 22.38% of the respondents have had an accident with a pedestrian, 11.90% have had accidents with automobiles, 7.14% have had their bicycle stolen, 11.90% reported that their bicycle had been damaged, and 26.67% reported that no bicycles were available. In contrast, 37.62% have not had any negative experiences with the system, and, in turn, 27.14% of the respondents classify the public bicycle system as a very safe means, 61.90% define it as only safe, 4.29% perceive it as unsafe, and 6.67% consider it very unsafe. Importantly, the respondents could select more than one option for this item.

However, before showing the results of the confirmatory factor analysis, the descriptive results of the research questionnaire used are shown below (see

Table 2):

Although the following section will show the analysis for each of the model factors, it is important to highlight that the descriptive results of the instrument show a strong tendency on the part of the participants to strongly agree (SA) and agree (A) with the questions asked. In this sense, it is highlighted that for only three (of the 16 questions investigated) there was a percentage below 50% who agreed (SN10, SN11, and SN12). In contrast, the questions associated with the construct ATT and PC presented acceptance levels (SA and A) above 60%. These results accord with what was found in the confirmatory factor analysis.

Below are the results associated with the confirmatory factor analysis.

4.1. Factor Analysis

Introduced by Spearman in 1904, factor analysis is a statistical method [

58] that correlates a set of observed variables as a function of latent factors or constructs [

59], evaluated based on observable variables in instruments, such as surveys or interviews, collecting an important type of validity evidence that allows researchers to explore or confirm these relationships [

60]. The objective of factor analysis is to quantify the degree to which each variable is associated with the factors or constructs and thus obtain information about their nature [

59].

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) allows determining the underlying factors or constructs that exist in a set of data or items [

61], and is used when a researcher does not have sufficient bases to form hypotheses about the covariance between the variables and the constructs, thus constituting a theory-generating method [

62]. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) is used to identify, explore and test whether a hypothetical structure is appropriate for multivariate data [

63], that is, to verify if any theoretical model previously formulated a priori explains the correlation between the observed variables [

64].

4.2. Convergent Validity

Instruments for measuring scientific activity are applicable only when such tools are supported by evidence of validity within the specific context in which the instrument is applied [

60,

65]. Convergent validity is defined as the association between tests that measure the same construct [

66] and the degree of relationship between two hypothetically related constructs, without ignoring that a greater association is expected in convergent validity than in discriminant validity [

67].

Factor loadings, which determine the correlation between the variables and the factors or constructs [

68], are considered adequate when individual values greater than 0.50 are obtained [

69]. As

Table 3 reveals, all the items have an optimal factorial load, with SN2 (second measurement item for the construct of subjective norm) having the highest value (0.924) and SN1 (first measurement item for the same construct of subjective norm) having the lowest value (0.587), which is still considered acceptable.

In turn, factorial loads are measured in a composite way based on their average, and their values must be greater than 0.70 [

70]. The construct with the highest average factor loading was attitude (0.810); in contrast, the construct with the lowest average factor loading was intention (0.722), but the value is considered acceptable.

To verify the suitability of the factor analysis, it is necessary to assess the adequacy of the sample by using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett sphericity tests, as evidenced in [

71]. This verification measures the robustness of the dataset [

72]. The KMO statistic, which allows comparison of the magnitudes of the correlation coefficients [

73], ranges from 0 to 1 [

72], with values equal to or greater than 0.5 considered adequate [

74]. However, some authors recommend values equal to or greater than 0.6 as the threshold for adequacy [

75].

The Bartlett test of sphericity, like the KMO statistic, assesses the suitability of the data for a factor analysis [

76] from other statistics, such as chi-square (X2), degrees of freedom (df) and confidence level (α) [

72], and considers values less than 0.001 as suitable.

Table 4 presents the KMO statistic for each construct and the Bartlett sphericity test result. The lowest KMO statistic was obtained for the SN construct (0.691), and the highest value was obtained for the ATT construct (0.763). For all constructs, the result of the Bartlett test of sphericity was 0.000, fulfilling the measurement criteria for both measures of suitability.

4.3. Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity, together with convergent validity, are two quantitative measures of the validity of the measurement of the constructs of a model [

64]. Discriminant validity has been fundamental in assessing the validity of measurements for many decades [

77] and is included in many investigations [

78].

Discriminant validity is considered the extent to which a latent variable discriminates from other latent variables. Therefore, a latent variable can explain more variance in the observed variables associated with it than in unmeasured external influences or in other constructs [

79]. In turn, discriminant validity can be defined as the degree of relationship between two constructs hypothesised to be different, so that the construct to be measured is measured [

80].

The evaluation of scales and tests of validity of measures is frequently associated with the application of CFA, using confidence intervals [

80], which according to the method described by [

81] should be 95%, with values of 1 for measuring a construct compared with itself.

Table 5 provides the discriminant validity assessment results, showing that none of the confidence interval measurements are equal to 1, except for those variables compared with themselves.

4.4. Reliability

Reliability is one of the two most important characteristics in evaluating any instrument for research [

82]. Reliability refers to the degree to which the measure is reliable or free of errors, and therefore to the degree to which a measure classifies individuals consistently [

83]. To understand structure and correlations, it is essential to examine the reliability of the latent variables directly [

84], and researchers must demonstrate reliability in their analyses so that other researchers transfer these models to different contexts [

85]. Therefore, there is a wide variety of reliability techniques [

85,

86], with Cronbach’s alpha (also called tau-equivalent reliability) being the most used objective measure of reliability [

80].

This measure of reliability indicates the stability of the score of a test during a period, presenting the consistency of the position of a respondent in two different measurements [

87], or from several partitions of the sample. Values are expressed as a number between 0 and 1 [

88], and a value is considered high when correlations between elements are greater than 0.7, which denotes good internal consistency between the variables that constitute the constructs [

89].

Table 6 shows the reliability values (Cronbach’s alpha), with all values greater than 0.7. The lowest coefficient, i.e., 0.793, corresponds to the intention construct, and the highest coefficient, i.e., 0.881, corresponds to the attitude construct.

4.5. Hypothesis Ccontrast

In some studies, it is of interest to determine the relationship between two or more variables, their degree of association, and the influence of one on another, and there are different procedures for making these determinations [

90]. The most widely used measurement coefficient of dependence intensity is the Cramér coefficient [

91], also known as Cramér’s V [

92].

Cramér’s V is a symmetric measure that relates the chi-square statistic with respect to the maximum value that can be reached [

93] and, in a simple way, indicates the degree of relationship between two or more variables [

94]. Cramér’s V statistic ranges from 0 to 1 [

91], with 1 indicating a maximum or perfect association and 0 indicating perfect independence [

93].

Specifically, Cramér’s V values ranging from 0 to 0.10 indicate a negligible effect, those that range from 0.10 to 0.30 indicate a small and nonsignificant effect, those that range from 0.30 to 0.50 indicate a moderate effect, and those that range from 0.50 to 1 indicate a large effect [

95]. In fact, a value greater than or equal to 0.60 is rarely obtained, with 0.30 being an acceptable intermediate empirical value [

93].

Table 7 provides the Cramér V statistics, as determined using SPSS 22 statistical software, for each hypothesis; acceptable values were obtained. Specifically, the lowest relationship, according to Cramér’s V statistic, is between ATT and SNs, with a value of 0.349 (moderate effect), and the strongest relationship is between ATT and BI, with a Cramér’s V value of 0.579 (large effect).

Cramér’s V statistics or Cramér’s coefficients were calculated;

Figure 3 presents the model and associations between variables or constructs:

5. Discussion

Although sustainability continues to be a problem in the current global context, the literature that addresses this issue by using different approaches continues to grow significantly, reflecting the importance of sustainability for individuals, companies, and the entire economy [

96].

A bibliometric analysis performed by [

97] showed that there has been an increase in studies that address sustainability from the perspective of the Theory of Planned Behaviour by Ajzen, reflecting the theory’s application to the understanding of behavioural factors in aspects such as waste management, green consumption, energy savings and sustainable transport. However, these studies have been presented primarily in the context of developed countries, such as the United States, China, the United Kingdom, and Malaysia, identifying the determinants of environmental behaviour in these countries.

In this sense, some studies, through the application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour, have tried to understand the behavioural factors that have greater incidence in the reduction in automobile use, for example [

98], which focuses only on the Chinese context.

This study of the Asian continent is supported by what was found in the research by [

47], who analysed the key factors in the shared use of bicycles in China as a mitigation strategy for unsustainable modes of use and in the behaviour of users by using the Theory of Planned Behaviour.

Other authors have directly analysed the behavioural factors that have a greater impact on understanding the intention to use a bicycle, but more from the recreational perspective than from the environmental or bicycles as a sustainable means of transport [

99] perspective. This approach is similar to what was used by [

100], who applied the Theory of Planned Behaviour to the behavioural factors for the use of helmets as a health protection or physical integrity measure during bicycle use.

Other authors have adopted psychometric methodologies for measuring the utility of bicycle use by tourists who temporarily inhabit urban areas [

101].

Therefore, considering that this conceptual model proposed by Ajzen is limited to use in cultural approaches [

102], the value of the present research is the application of this psychometric methodology to the context of a developing country such as Colombia, specifically in the city of Medellín, to understand the main behavioural factors for users of the public or shared bicycle system EnCicla.

Specifically, the variable that further explained the behavioural intention of the users of the public bicycle programme EnCicla was attitude towards behaviour; according to [

38], this attitude is the extent to which a person has a favourable or unfavourable assessment of what is being analysed.

Therefore, knowing that attitude towards behaviour largely explains behavioural intention, those responsible for the internal analysis of and decision making for the EnCicla programme can implement strategies that strengthen the attitude of its users through dynamics that facilitate improvements in users’ overall assessment of the public bicycle system; this will, in turn, increase service satisfaction [

103].

To achieve the above, it is necessary for bicycle systems, such as EnCicla, to consider collaborations with other institutions that may favour improvements in attitudes towards behaviour, for example, companies that through their organisational policies can motivate employees to contribute to sustainable mobility.

The results from this research can serve as a reference for other researchers to validate the adoption of sustainable mobility strategies, specifically the use of public or shared bicycle systems and their respective behavioural factors, in social, economic and educational contexts similar to those of the city of Medellín, as one of the main cities of a developing country.

This work serves as a starting point; based on multiple qualitative validations with users of different public bicycle systems, researchers can investigate the different actions for improving and strengthening the systems under study in their own contexts and with their own inherent characteristics.

Finally, it is important to mention that the limitations of this study are related to the size of the sample used; although the sample size is adequate for exploratory studies, it could be expanded for future research. In addition, researchers interested in the subject are invited to validate the proposed model in contexts other than the one used in this study.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated the main behavioural factors in the use of the EnCicla public bicycle system in the city of Medellín because bicycles are a growing alternative as a sustainable means of transport. Important findings were made, beginning with confirmation that the Theory of Planned Behaviour is an ideal psychometric methodology for understanding the main behavioural factors in using public bicycles in the context studied, improving the current understanding of sustainable use behaviour and the intentions towards use of EnCicla users.

The different latent variables or constructs are important in understanding the behavioural intentions of the users of the EnCicla public bicycle system from a sustainable or environmental perspective.

Specifically, the variables attitude towards behaviour, perceived behavioural control and subjective norms, explained behavioural intentions with positive correlations and impacts. In turn, the constructs of attitude towards behaviour and perceived behavioural control presented the most important internal correlation; therefore, it is concluded that they are the two main constructs that explain the intentions towards the behaviour of users of the mentioned programme.

Finally, identifying the key latent variables to understand the intentions towards behaviour, representing the most important behavioural factor, allows those in charge of the EnCicla public bicycle programme to address important factors when analysing, on the one hand, the adoption of the programme and, on the other hand, the perceived satisfaction of the users of the programme. This would facilitating the potentiation and expansion of its scope for the social, economic and environmental benefits of the city; the programme serves, therefore, as an application model for contextually similar cities and as a theoretical reference for future research on other public bicycle systems, expanding the practical and theoretical margins of behavioural factors that affect sustainability.

7. Practical Implications

Based on the results obtained, the public authorities of cities and countries contextually similar to the case study in this paper will be able to adopt practical (implementation) measures and public policies that allow the implementation of sustainable mobility programs, such as EnCicla. In those cases that already exist, these results will allow the design of strategies to increase user satisfaction and increase the use of the system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, J.B.-H. and A.V.-A.; methodology, S.C.-A., A.V.-A. and L.P.-M.; software, J.B.-H. and N.D.L.; validation, N.D.L.; formal analysis, S.C.-A. and A.V.-A.; investigation, S.C.-A., A.V.-A. and L.P.-M.; resources, L.P.-M. and N.D.L.; data curation, J.B.-H., A.V.-A. and N.D.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C.-A. and L.P.-M.; writing—review and editing, S.C.-A., A.V.-A. and N.D.L.; visualization, J.B.-H. and N.D.L.; supervision, J.B.-H., A.V.-A. and L.P.-M.; project administration, A.V.-A.; funding acquisition, A.V.-A., L.P.-M. and N.D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project received external funding (PE13072020) from the following universities Instituto Tecnológico Metropolitano (Colombia), Institución Universitaria Escolme (Colombia), and Universidad Señor de Sipán (Perú). The APC was funded by Universidad Señor de Sipán (Perú).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Sarasma, J.J. Changing Mobility Practices during the COVID-19 Pandemic. What Can Practice Theory Teach Us about Sustainable Mobility in Finland. 2021. Available online: https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/333891 (accessed on 18 January 2022).

- Holden, E.; Banister, D.; Gössling, S.; Gilpin, G.; Linnerud, K. Grand Narratives for sustainable mobility: A conceptual review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 65, 101454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisi, T.; Basbas, S.; Skoufas, A.; Akgün, N.; Ticali, D.; Tesoriere, G. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the resilience of sustainable mobility in sicily. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisi, T.; Garau, C.; Acampa, G.; Maltinti, F.; Canale, A.; Coni, M. Developing flexible mobility on-demand in the era of mobility as a service: An overview of the Italian context before and after pandemic. In International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 323–338. [Google Scholar]

- Vecchio, G.; Tiznado-Aitken, I.; Mora-Vega, R. Pandemic-related streets transformations: Accelerating sustainable mobility transitions in Latin America. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2021, 9, 1825–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conticelli, E.; Gobbi, G.; Saavedra Rosas, P.I.; Tondelli, S. Assessing the performance of modal interchange for ensuring seamless and sustainable mobility in European cities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbarossa, L. The post pandemic city: Challenges and opportunities for a non-motorized urban environment. An overview of Italian cases. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šťastná, M.; Vaishar, A.; Zapletalová, J.; Ševelová, M. Cycling: A benefit for health or just a means of transport? Case study Brno (Czech Republic) and its surroundings. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2018, 55, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapuku, C.; Kho, S.-Y.; Kim, D.-K.; Cho, S.-H. Modeling the competitiveness of a bike-sharing system using bicycle GPS and transit smartcard data. Transp. Lett. 2020, 14, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macioszek, E.; Świerk, P.; Kurek, A. The bike-sharing system as an element of enhancing sustainable mobility—A case study based on a city in Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eastman, J.A.S. El uso de la bicicleta como promotor de la movilidad sostenible: Acciones y efectos en la movilidad cotidiana, el mejoramiento de la calidad del aire y el transporte público de las ciudades. Rev. Kavilando 2020, 12, 118–126. [Google Scholar]

- Diogo, V.; Sanna, V.S.; Bernat, A.; Vaičiukynaitė, E. In the scenario of sustainable mobility and pandemic emergency: Experiences of bike- and e-scooter-sharing schemes in Budapest, Lisbon, Rome and Vilnius. In Becoming a Platform in Europe: On the Governance of the Collaborative Economy; Teli, M., Bassetti, C., Eds.; Now Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 59–89. [Google Scholar]

- Farag, A.A. How sustainable is mobility in cities branded the happiest? In Linking Sustainability and Happiness. Community Quality-of-Life and Well-Being; Cloutier, S., El-Sayed, S., Ross, A., Weaver, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 151–174. [Google Scholar]

- Sudmant, A.; Mi, Z.; Oates, L.; Tian, X.; Gouldson, A. Towards Sustainable Mobility and Improved Public Health: Lessons from Bike Sharing in Shanghai, China. 2020. Available online: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/158439/ (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Simović, S.; Ivanišević, T.; Trifunović, A.; Čičević, S.; Taranović, D. What affects the e-bicycle speed perception in the era of eco-sustainable mobility: A driving simulator study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petri, M.; Pratelli, A. SaveMyBike—A complete platform to promote sustainable mobility. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2019; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 177–190. [Google Scholar]

- Vélez-Chávez, C.O. Movilidad sustentable y saludable en bicicleta por tiempos de Covid en la ciudad de Manta. Polo Conoc. 2021, 6, 656–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnabelseya, B.; Beaudry, M.; Hotte, M.; Tebinka, R. Public Engagement in Sustainable Mobility Projects. 2021. Available online: https://trid.trb.org/view/1887365 (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Torres, N.; Martins, P.; Pinto, P.; Lopes, S.I. Smart & sustainable mobility on campus: A secure IoT tracking system for the BIRA bicycle. In Proceedings of the 2021 16th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), Chaves, Portugal, 23–26 June 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Saif, M.A.; Zefreh, M.M.; Torok, A. Public transport accessibility: A literature review. Period. Polytech. Transp. Eng. 2018, 47, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Medina, C.D.T. Urban regeneration of Medellin. An example of sustainability. UPLanD J. Urban Plan. Landsc. Environ. Des. 2018, 3, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguelovski, I.; Irazábal-Zurita, C.; Connolly, J.J.T. Grabbed urban landscapes: Socio-spatial tensions in green infrastructure planning in medellín. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2019, 43, 133–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Arias, A.; Urrego-Marín, M.L.; Bran-Piedrahita, L. A methodological model to evaluate smart city sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, J.; Ryan, B.; Bearman, C.; Toh, K. Should we leave now? Behavioral factors in evacuation under wildfire threat. Fire Technol. 2019, 55, 487–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Huang, A.F.; Wang, T.-Y.; Chen, Y.-R. Greenwash and green purchase behaviour: The mediation of green brand image and green brand loyalty. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2020, 31, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.; Im, M.; Song, M.R.; Park, J. Psychological and behavioral factors affecting electric vehicle adoption and satisfaction: A comparative study of early adopters in China and Korea. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 76, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giorgio, E.; Di Riso, D.; Mioni, G.; Cellini, N. The interplay between mothers’ and children behavioral and psychological factors during COVID-19: An Italian study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 30, 1401–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action Control; SSSP Springer Series in Social Psychology; Kuhl, J., Beckmann, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, A.; Emami, N.; Damalas, C.A. Farmers’ behavior towards safe pesticide handling: An analysis with the theory of planned behavior. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 751, 141709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, Personality and Behaviour; McGraw-Hill Education: Berkshire, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ubillos, S.; Páez, D.; Mayordomo, S. Actitudes: Definición y medición. Componentes de la actitud. Modelo de acción razonada y acción planificada. In Psicología Social, Cultura y Educación; Páez, D., Fernández, I., Ubillos, S., Zubieta, E., Eds.; Pearson Educación: Madrid, Spain, 2004; pp. 301–326. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, D.; Johnson, K.K.P. Influences of environmental and hedonic motivations on intention to purchase green products: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 18, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, M.; Carter, L.; Phillips, B. Integrating the theory of planned behavior and behavioral attitudes to explore texting among young drivers in the US. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 50, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Deng, W.; Hu, Q. Using the theory of planned behavior to understand traffic violation behaviors in e-bike couriers in China. J. Adv. Transp. 2021, 2021, 2427614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schifter, D.E.; Ajzen, I. Intention, perceived control, and weight loss: An application of the theory of planned behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 49, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asare, M. Using the theory of planned behavior to determine the condom use behavior among college students. Am. J. Health Stud. 2020, 30, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trafimow, D.; Sheeran, P.; Conner, M.; Finlay, K.A. Evidence that perceived behavioural control is a multidimensional construct: Perceived control and perceived difficulty. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 41, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, R.T.; Sube, B.E.C.; Laforga, A.G. Wondering wanderers: Travel behavior of employees within NCR plus bubble amid pandemic. J. Econ. Finance Account. Stud. 2022, 4, 565–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Wong, R.M. Vaccine hesitancy and perceived behavioral control: A meta-analysis. Vaccine 2020, 38, 5131–5138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pender, N.J.; Pender, A.R. Attitudes, subjective norms, and intentions to engage in health behaviors. Nurs. Res. 1986, 35, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lina, H.; Quanlong, L.; Xinchun, L. De la intención al comportamiento: Modelo analítico del comportamiento de riesgo moral del médico basado en la teoría del comportamiento planificado. Acta Bioethica 2020, 26, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Barbera, F.; Ajzen, I. Control interactions in the theory of planned behavior: Rethinking the role of subjective norm. Eur. J. Psychol. 2020, 16, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S. Assessing the moderating effect of subjective norm on luxury purchase intention: A study of Gen Y consumers in India. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2020, 48, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savari, M.; Gharechaee, H. Application of the extended theory of planned behavior to predict Iranian farmers’ intention for safe use of chemical fertilizers. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, H.; Shi, J.-G.; Tang, D.; Wu, G.; Lan, J. Understanding intention and behavior toward sustainable usage of bike sharing by extending the theory of planned behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 152, 104513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I.; Waris, I.; Amin ul Haq, M. Predicting eco-conscious consumer behavior using theory of planned behavior in Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 15535–15547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S. The advantages and disadvantages of using qualitative and quantitative approaches and methods in language “testing and assessment” research: A literature review. J. Educ. Learn. 2016, 6, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F.; Thorpe, C.T. Scale Development: Theory and Applications; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Swedberg, R. Exploratory research. In The Production of Knowledge: Enhancing Progress in Social Science; Elman, C., Gerring, J., Mahoney, J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 17–41. [Google Scholar]

- Giraldo, M.C.B.; Valencia-Arias, A.; García, B.D.; Garcés-Giraldo, L.F.; Luna-Ramírez, T. Factores de uso de los medios de pago móviles en millennials y centennials. Semest. Econ. 2019, 22, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makan, R.; Gara, M.; Awwad, M.A.; Hassona, Y. The oral health status of Syrian refugee children in Jordan: An exploratory study. Spec. Care Dent. 2019, 39, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, J.-H.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Ramayah, T.; Ting, H. Convergent validity assessment of formatively measured constructs in PLS-SEM: On using single-item versus multi-item measures in redundancy analyses. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 3192–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, F. SPSS (Software). In The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Purwanto, A.; Asbari, M.; Santoso, T.I.; Paramarta, V.; Sunarsi, D. Social and management research quantitative analysis for medium sample: Comparing of Lisrel, Tetrad, GSCA, Amos, SmartPLS, WarpPLS, and SPSS. J. Ilm. Ilmu Adm. Publik 2020, 10, 518–532. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, W. Influence of particle size and extraction time on soil pH analysis based on SPSS software. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1549, 022125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A. Confirmatory factor analysis. In Structural Equations with Latent Variables; Bollen, K.A., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 226–318. [Google Scholar]

- Bandalos, D.L.; Finney, S.J. Factor analysis: Exploratory and confirmatory. In The Reviewer’s Guide to Quantitative Methods in the Social Sciences; Hancock, G.R., Stapleton, L.M., Mueller, R.O., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 98–122. [Google Scholar]

- Knekta, E.; Runyon, C.; Eddy, S. One size doesn’t fit all: Using factor analysis to gather validity evidence when using surveys in your research. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 2019, 18, rm1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goretzko, D.; Pham, T.T.H.; Bühner, M. Exploratory factor analysis: Current use, methodological developments and recommendations for good practice. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 3510–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, C.D. Basic Concepts and Procedures of Confirmatory Factor Analysis. 1997. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED407416 (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Sarmento, R.P.; Costa, V. Confirmatory factor analysis—A case study. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.05598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, M.T.H.; Tran, T.D.; Holton, S.; Nguyen, H.T.; Wolfe, R.; Fisher, J. Reliability, convergent validity and factor structure of the DASS-21 in a sample of Vietnamese adolescents. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amora, J.T. Convergent validity assessment in PLS-SEM: A loadings-driven approach. Data Anal. Perspect. J. 2021, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, D.T.; Fiske, D.W. Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychol. Bull. 1959, 56, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chang, K.-C.; Hou, W.-L.; Pakpour, A.H.; Lin, C.-Y.; Griffiths, M.D. Psychometric testing of three COVID-19-related scales among people with mental illness. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caycho-Rodríguez, T.; Vilca, L.W.; Cervigni, M.; Gallegos, M.; Martino, P.; Portillo, N.; Barés, I.; Calandra, M.; Burgos Videla, C. Fear of COVID-19 scale: Validity, reliability and factorial invariance in Argentina’s general population. Death Stud. 2020, 46, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwanti, Y. The influence of digital marketing & innovasion on the school performance. Turk. J. Comput. Math. Educ. 2021, 12, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, A.; Yusop, F.D.; Razak, R.A. The dataset for validation of factors affecting pre-service teachers’ use of ICT during teaching practices: Indonesian context. Data Brief 2019, 28, 104875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algeo, T.J.; Liu, J. A re-assessment of elemental proxies for paleoredox analysis. Chem. Geol. 2020, 540, 119549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korauš, A.; Dobrovič, J.; Polák, J.; Backa, S. Aspects of the security use of payment card pin code analysed by the methods of multidimensional statistics. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2019, 6, 2017–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, E.; Matthews, G.; Cox, T. The appraisal of life events (ALE) scale: Reliability and validity. Br. J. Health Psychol. 1999, 4, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Zhao, X.; Tao, Y.; Mi, S.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Q. The effects of air pollution and meteorological factors on measles cases in Lanzhou, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 13524–13533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Fernández, M.; Gracia, E.; Marco, M.; Vargas, V.; Santirso, F.A.; Lila, M. Measuring acceptability of intimate partner violence against women: Development and validation of the A-IPVAW scale. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Leg. Context 2018, 10, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matthes, J.M.; Ball, A.D. Discriminant validity assessment in marketing research. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2019, 61, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spuling, S.M.; Klusmann, V.; Bowen, C.E.; Kornadt, A.E.; Kessler, E.-M. The uniqueness of subjective ageing: Convergent and discriminant validity. Eur. J. Ageing 2019, 17, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshanloo, M. Structural and discriminant validity of the tripartite model of mental well-being: Differential relationships with the big five traits. J. Ment. Health 2017, 28, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rönkkö, M.; Cho, E. An updated guideline for assessing discriminant validity. Organ. Res. Methods 2020, 25, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, B.A.; Ripoll, M.; Angulo, A. Evidence of reliability and validity of an instrument to assess pedagogical reflection. Educ. Super. 2021, 8, 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hedge, C.; Powell, G.; Sumner, P. The reliability paradox: Why robust cognitive tasks do not produce reliable individual differences. Behav. Res. Methods 2018, 50, 1166–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Forbes, M.K.; Greene, A.L.; Levin-Aspenson, H.F.; Watts, A.L.; Hallquist, M.; Lahey, B.B.; Markon, K.E.; Patrick, C.J.; Tackett, J.L.; Waldman, I.D.; et al. Three recommendations based on a comparison of the reliability and validity of the predominant models used in research on the empirical structure of psychopathology. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2021, 130, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, F.M.; Finkenstaedt-Quinn, S.A. The current state of methods for establishing reliability in qualitative chemistry education research articles. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2021, 22, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.; Johnson, C.W. Contextualizing reliability and validity in qualitative research: Toward more rigorous and trustworthy qualitative social science in leisure research. J. Leis. Res. 2020, 51, 432–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J.; Warrington, W.G. Time-limit tests: Estimating their reliability and degree of speeding. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaam, E.A.; Bakar, K.A.A.; Satar, N.S.M.; Ma’arif, M.Y. Investigating the electronic customer relationship management success key factors in the telecommunication companies: A pilot study. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. 2020, 17, 1460–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, T.H.T.; Kwok, S.T.; Wang, W.; Seto, M.T.Y.; Cheung, K.W. Fear of childbirth: Validation study of the Chinese version of Wijma delivery expectancy/experience questionnaire version B. Midwifery 2022, 108, 103296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez, M.R.; Vilà-Baños, R.; Torrado-Fonseca, M. La relación entre dos variables según la escala de me-dición con SPSS. REIRE. Rev. Innov. Recer. Educ. 2018, 11, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gresakova, E.; Chlebikova, D. Time management of non-profit sector managers in the context of globalization. SHS Web Conf. 2021, 92, 02019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, M.Y.; Kasyanov, E.D.; Rukavishnikov, G.V.; Makarevich, O.V.; Neznanov, N.G.; Morozov, P.V.; Lutova, N.B.; Mazo, G.E. Stress and stigmatization in health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Indian J. Psychiatry 2020, 62, S445–S453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Roldán, P.; Fachelli, S. Metodología de la Investigación Social Cuantitativa. Dipòsit Digital de Documents; Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona: Bellaterra, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tsoklinova, M.A.; Delkov, A.N. Factors inducing on consumption of ecosystem service tourism. J. Balk. Ecol. 2019, 22, 291–301. [Google Scholar]

- Velásquez, A.C.B.; Niño, I.L.C. Metodología de correlación estadística de un sistema integrado de gestión de la calidad en el sector salud. SIGNOS Investig. Sist. Gest. 2018, 10, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobanee, H.; Al Hamadi, F.Y.; Abdulaziz, F.A.; Abukarsh, L.S.; Alqahtani, A.F.; AlSubaey, S.K.; Alqahtani, S.M.; Almansoori, H.A. A bibliometric analysis of sustainability and risk management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, H.; Shi, J.-G.; Tang, D.; Wen, S.; Miao, W.; Duan, K. Application of the theory of planned behavior in environmental science: A comprehensive bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Sheng, H.; Mundorf, N.; Redding, C.; Ye, Y. Integrating norm activation model and theory of planned behavior to understand sustainable transport behavior: Evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Bruijn, G.-J.; Kremers, S.P.J.; Singh, A.; van den Putte, B.; van Mechelen, W. Adult active transportation. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lajunen, T.; Räsänen, M. Can social psychological models be used to promote bicycle helmet use among teenagers? A comparison of the health belief model, theory of planned behavior and the locus of control. J. Saf. Res. 2004, 35, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, S.; Manca, F.; Nielsen, T.A.S.; Prato, C.G. Intentions to use bike-sharing for holiday cycling: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, B.; Afiff, A.Z.; Heruwasto, I. Integrating the theory of planned behavior with norm activation in a pro-environmental context. Soc. Mark. Q. 2020, 26, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echendu, A.J. Critical appraisal of an example of best practice in urban sustainability. Cent. Eur. J. Geogr. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 3, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).